Abstract

Objective

To assess rehabilitation infrastructure in Peru in terms of WHO Health System Building Blocks.

Design

Anonymous quantitative survey. Questions were based on WHO Guidelines for Essential Trauma Care and rehabilitation professionals’ input.

Setting

Nine large public hospitals and referral centers in Lima and an online survey platform.

Participants

Convenience sample of hospital personnel working in rehabilitation and neurology, recruited through existing contacts and professional societies.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measure

Outcome measures were for four WHO domains: Health Workforce, Health Service Delivery, Essential Medical Products and Technologies, and Health Information Systems.

Results

There were 239 survey participants. Regarding ‘Health Workforce,’ 47% of PTs, 50% of OTs, and 22% of physiatrists never see inpatients. Few reported rehabilitative nurses (15%) or prosthetist/orthotists (14%) at their hospitals. Even at the largest hospitals, most reported three or fewer occupational therapists (OTs, 54%) and speech language pathologists (SLPs, 70%). At hospitals without SLPs, PTs (49%) or nobody (34%) performs SLP roles. At hospitals without OTs, PTs most commonly (59%) perform OT tasks. Alternate prosthetist/orthotist task performers are OTs (26%), PTs (19%), and physicians (16%). Forty-four percent reported interdisciplinary collaboration.

Regarding ‘Health Services,’ the most frequent inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation barriers were referral delays (50%) and distance/transportation (39%), respectively. Regarding ‘Health Information Systems,’ 28% reported rehabilitation service data collection. Regarding ‘Essential Medical Products and Technologies,’ electrophysical agents (88%), gyms (81%), and electromyography (76%) were most common; thickened liquids (19%), swallow studies (24%), and cognitive training tools (28%) were least frequent.

Conclusions

Rehabilitation emphasis is on outpatient services, and there are comparatively adequate numbers of PTs and physiatrists relative to rehabilitation personnel. Financial barriers seem low for accessing existing services. There appear to be shortages of inpatient rehabilitation, specialized services, and interdisciplinary collaboration. These may be addressed by redistributing personnel and investing in education and equipment for specialized services. Further examination of task sharing’s role in Peru’s rehabilitation services is necessary to evaluate its potential to address deficiencies.

Keywords: Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Peru, Disability, World Health Organization, Health Services, Health Personnel, Health Information Systems, Interdisciplinary Communication, Interdisciplinary Health Team, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapy, Speech-Language Pathology, Rehabilitation Nursing

INTRODUCTION

Persons with disability (PWD) only recently have been recognized as a distinct target group for public health interventions, and health information on PWD varies between countries.1–3 In examining injury as a cause of disability, The Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors study estimated injuries to account for 20% of ill health in the world by 2020, while for every injury-related death, 10–50 times more people survive injury with some permanent disability.4,5 In total, over one billion people live with some form of disability, and eight of ten persons with disability (PWD) live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1

The scarce existing data suggest that this population is largely without access to rehabilitation services, and there appear to be disparities across countries and regions in the numbers and distribution of rehabilitation personnel.6 Studies from Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, and Swaziland revealed that just 26–55% of PWD were able to obtain their necessary medical rehabilitation, while only 17–37% received the assistive devices (e.g. wheelchairs) they required.1 Further, in Mexico, Vietnam, India, and Ghana, investigators found a lack of human resources for rehabilitation, with the near absence of essential specialized rehabilitative services, such as speech pathology and rehabilitative nursing.7 Health disparities for PWD and deficiencies in rehabilitation accessibility are likely even more pronounced in rural areas of LMICs; studies in Pakistan and Ghana have shown fewer rehabilitation facilities, personnel, and rehabilitation-related NGOs, as well as greater perceived stigma of disability in rural areas of these countries.8,9

Rehabilitation reduces hospital stays and thereby costs, reduces disability, and improves quality of life.1 Following stroke and traumatic brain injury, timely formal swallow screening and subsequent evaluation by specialized rehabilitation personnel are effective in preventing aspiration, pneumonia, and death.10,11 In one randomized controlled trial (RCT), a formalized dysphagia screening protocol for stroke survivors was associated with a 3% absolute reduction in pneumonia.10 Proper splinting and range-of-motion and strengthening exercises maximize function and reduce disability following extremity injuries like burns and fractures; the World Health Organization (WHO) has thus deemed basic physical/occupational therapy essential at all hospital levels.12

However, no standardized measurement of comprehensive rehabilitation care exists, and very few studies have attempted to quantify rehabilitation capacity in LMICs.1,6 To date, adequacy of rehabilitation services has not been assessed in Peru, and as in most LMICs, there are little to no data on disability prevalence in the country.6 However, the magnitude of Peru’s need for rehabilitation services is presumably large, given the high national prevalence of road traffic injuries and stroke.13,14 During the 35-year period of 1973–2008, there were 952,668 road traffic victims injured or killed, and the adjusted yearly incidence of road traffic accidents increased by 3.59 on average.13 Meanwhile, a population-based study of Peruvians age 65 years and older described a 6.8% prevalence of self-reported stroke in urban areas, where stroke was also reported to account for 28.6% of death among residents.14,15

We sought to characterize the existing rehabilitation system in Peru according to the WHO building blocks—discrete components identified as essential to health system function and universally applicable as a monitoring, evaluation, and action framework16—in order to determine and prioritize next steps for improving disability outcomes in the country.

METHODS

Ethics Committee approval was obtained from the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and the University of Washington.

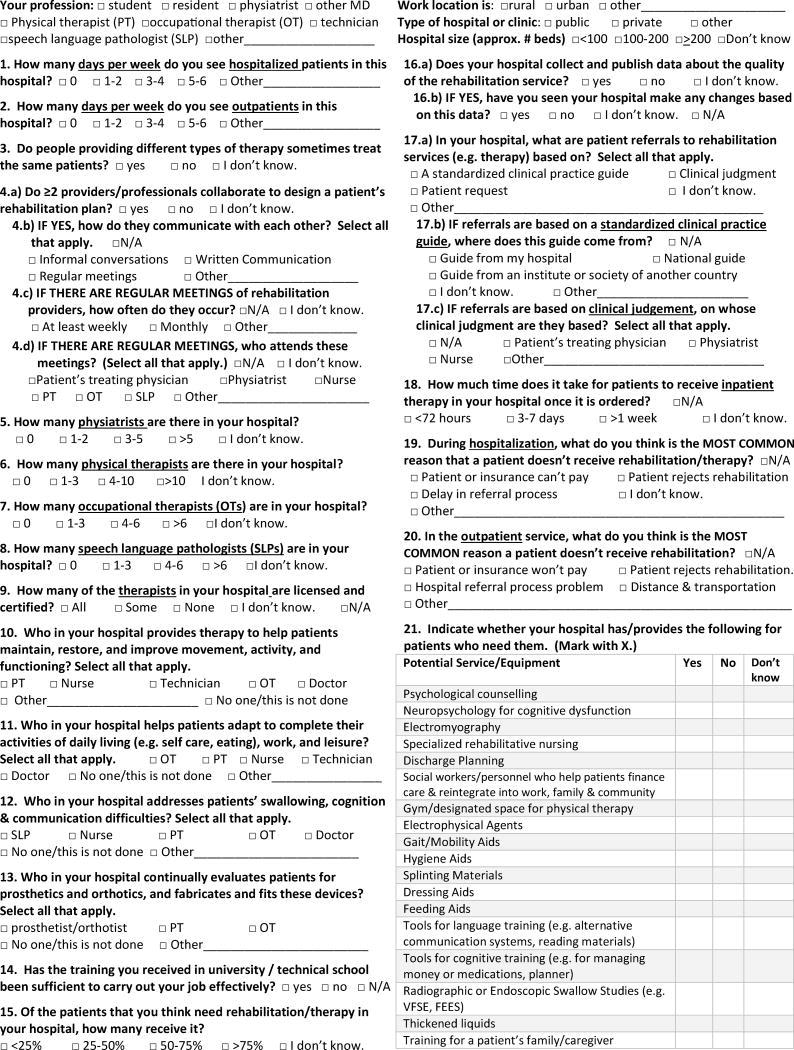

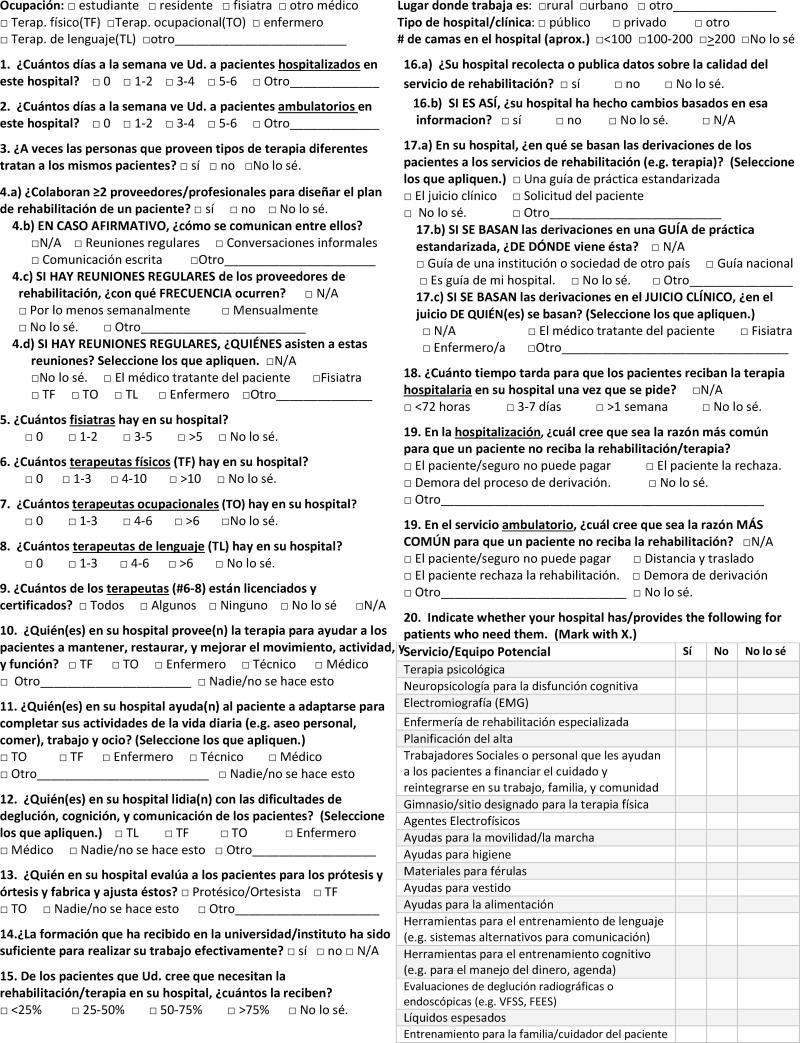

A single-page, anonymous survey was developed based on the WHO’s Guidelines for Essential Trauma Care12 and experience of rehabilitation professionals in both the United States and Peru. It was designed to address four of the six building blocks for health systems. These four were: Health Workforce, Health Service Delivery, Essential Medical Products and Technologies, and Health Information Systems. It did not address the remaining two WHO building blocks, Leadership and Governance or Finance, as it was a survey of end-users who were not anticipated to have adequate knowledge to comment on these factors.

The survey included questions regarding respondent demographics, hospital descriptors, and measures of rehabilitation practices, including basis of rehabilitation referrals, presence of specific personnel and equipment, adequacy of staff training, and patient coverage.

The questionnaire was developed in Spanish and was validated by a native Spanish speaker. Translation for the supplementary material was done by the first author, a bilingual native English speaker with a Spanish degree and training in Spanish translation. Survey forms in English and Spanish are included as Appendices 1 and 2, respectively.

Data were collected in Lima (Peru’s capital city) at one specialized neurologic institute and eight other large public (i.e. public health and social security) hospitals, which were identified by researchers’ professional contacts to have significant rehabilitation volume; there are no dedicated inpatient rehabilitation facilities in Lima. Surveys were distributed to personnel working in rehabilitation and/or neurology departments in these hospitals (i.e. physicians, therapists, nurses, and technicians).

Data were also collected via a secure online platform (REDCap - Research Electronic Data Capture, www.project-redcap.org). The survey link was distributed through three primary methods. First, a list of e-mail addresses for potential subjects was acquired through professional contacts, including those encountered during in-person data collection. These people were emailed the survey link along with the request that they distribute it to colleagues in their hospital and/or professional society. Second, the link was distributed online via national organization listservs for the Peruvian Rehabilitation Medicine Society, Peruvian Neurologic Society, and Peruvian Association of Physical Therapists. Third, the link was posted on the Facebook group of the Peruvian Association of Physical Therapists. Mass reminders were sent four times, approximately weekly, to listserv and email contacts, and the link was re-posted on Facebook three times. All electronic reminders included a sentence thanking people who had already completed the survey and another specifying that the link was for those who had not yet done so.

For in-person data collection, inclusion criteria were clinical staff currently working in the hospitals’ rehabilitation or neurology departments, specifically physicians, PTs, OTs, SLPs, P&Os, and nurses. For data collected through the online survey, people working in the above rehabilitation professions at hospitals with inpatient rehabilitation services were specifically targeted by the written survey invitations in effort to exclude those working only at private outpatient centers, who would not be able to answer many of the survey questions.

The researchers asked about department size in terms of personnel at in-person data collection to determine an approximate response rate. For the online surveys, response rate was calculated based of the number of people who answered in REDCap out of the total listserv (per listserv administrator) and Facebook group membership.

The dataset was exported to Stata 14 (StataCorp, TX, USA) for statistical analyses. Duplicate values were checked for to discard the possibility of double tabulating a single participant’s response. Descriptive analyses were performed, and categorical variables are presented as percentages. Numerical variables were not collected.

RESULTS

A total of 239 surveys were collected between March and May 2016. Of those, 128 were collected in person at the Lima hospitals. Between 11 and 24 surveys were collected at each institution, reflecting a 40–70% response rate. The other 111 were collected via the online survey platform, about a 20% response rate.

Health Workforce

Survey participant demographics by profession, hospital type and size, and their inpatient and outpatient service are detailed in Table 1. A breakdown of professionals by hospital size is shown in Table 2. When considering only rehabilitation specialists (i.e. physiatrists, PTs, OTs, and SLPs), a great proportion (39%) of respondents reported never seeing hospitalized patients. Specifically, 47% of PTs, 50% of OTs, and 22% of physiatrists never saw inpatients.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Location of hospital where you work | ||

| Urban | 225 | 94 |

| Rural | 6 | 2.5 |

| Other/Blank | 8 | 3.3 |

| Type of hospital where you work | ||

| Public | 183 | 77 |

| Private | 39 | 16 |

| Other/Blank | 17 | 7.1 |

| Size of hospital where you work (# of beds) | ||

| <100 | 48 | 20 |

| 100–200 | 23 | 9.6 |

| >200 | 95 | 40 |

| I don’t know/Blank | 73 | 31 |

| Profession | ||

| Physician* | 76 | 32 |

| Nurse | 2 | 0.8 |

| Physical Therapist | 105 | 44 |

| Occupational Therapist | 6 | 2.5 |

| Speech Language Pathologist | 10 | 4.2 |

| Other** | 20 | 8.4 |

| Blank | 20 | 8.4 |

| Days per week seeing hospitalized patients | ||

| Never | 66 | 28 |

| 1–2 | 50 | 21 |

| 3–4 | 40 | 17 |

| 5–6 | 67 | 28 |

| Other | 16 | 6.7 |

| Days per week seeing outpatients | ||

| Never | 11 | 4.6 |

| 1–2 | 23 | 9.6 |

| 3–4 | 25 | 10 |

| 5–6 | 164 | 69 |

| Other | 16 | 6.7 |

Physiatrists, residents and other physicians

Technician, students and others

Table 2.

Rehabilitation professionals by hospital size

| <100 Beds | 100–200 Beds | >200 Beds | I don’t know | Total (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | ||

| Physiatrists | |||||

| 0 | 24 (34%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (4.0%) | 3 (6.0%) | 34 |

| 1–2 | 18 (25%) | 6 (23%) | 9 (8.9%) | 5 (10%) | 38 |

| 3–5 | 12 (17%) | 9 (34%) | 22 (22%) | 11 (22%) | 54 |

| >5 | 15 (21%) | 6 (23%) | 57 (56%) | 28 (56%) | 106 |

| I don’t know | 2 (2.8%) | 2 (7.7%) | 9 (7.7%) | 3 (6.0%) | 16 |

| Total (N) | 71 | 26 | 101 | 50 | 248 |

| Physical Therapists | |||||

| 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| 1–3 | 29 (41%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (4.0%) | 4 (7.8%) | 40 |

| 4–10 | 17 (24%) | 8 (32%) | 12 (12%) | 7 (14%) | 44 |

| >10 | 24 (34%) | 12 (48%) | 75 (74%) | 37 (73%) | 148 |

| I don’t know | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (8.0%) | 10 (9.9%) | 3 (5.9%) | 16 |

| Total (N) | 71 | 25 | 101 | 51 | 248 |

| Occupational Therapists | |||||

| 0 | 37 (52%) | 7 (27%) | 19 (27%) | 12 (24%) | 75 |

| 1–3 | 17 (24%) | 10 (39%) | 36 (39%) | 14 (28%) | 77 |

| 4–6 | 6 (8.5%) | 2 (7.7%) | 24 (7.7%) | 18 (36%) | 50 |

| >6 | 10 (14%) | 1 (3.8%) | 7 (3.8%) | 2 (4.0%) | 20 |

| I don’t know | 1 (1.4%) | 6 (23%) | 15 (23%) | 4 (8.0%) | 26 |

| Total (N) | 71 | 26 | 101 | 50 | 248 |

| Speech Language Pathologists | |||||

| 0 | 29 (41%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (4.0%) | 6 (12%) | 43 |

| 1–3 | 26 (37%) | 15 (58%) | 66 (66%) | 26 (51%) | 133 |

| 4–6 | 6 (8.6%) | 1 (3.8%) | 14 (14%) | 12 (24%) | 33 |

| >6 | 7 (10%) | 2 (7.7%) | 6 (6.0%) | 3 (5.9%) | 18 |

| I don’t know | 2 (2.9%) | 4 (15%) | 10 (10%) | 4 (7.8%) | 20 |

| Total (N) | 70 | 26 | 100 | 51 | 247 |

In terms of other specialized rehabilitation services, 79% of participants reported the availability of psychological counseling, 55% reported social work, 34% reported neuropsychology for cognitive dysfunction, and only 15% reported specialized rehabilitative nursing. Just under half reported that discharge planning (43%) and family/caregiver training (46%) were provided at their hospitals.

Licensure, Certification, and Education

Approximately half of respondents stated all therapists (i.e. PTs, OTs, SLPs) at their hospitals were licensed and certified to practice in accordance with regulatory body requirements. One in four said only some were licensed and certified, while the remaining quarter were uncertain of therapists’ licensure and certification statuses.

Approximately half of rehabilitation specialists, whom we considered to most precisely represent the “rehabilitation workforce,” reported that their education did not sufficiently prepare them for their jobs. PTs and OTs were most likely to feel inadequately trained (50%), followed by SLPs (40%), then physiatrists (33%).

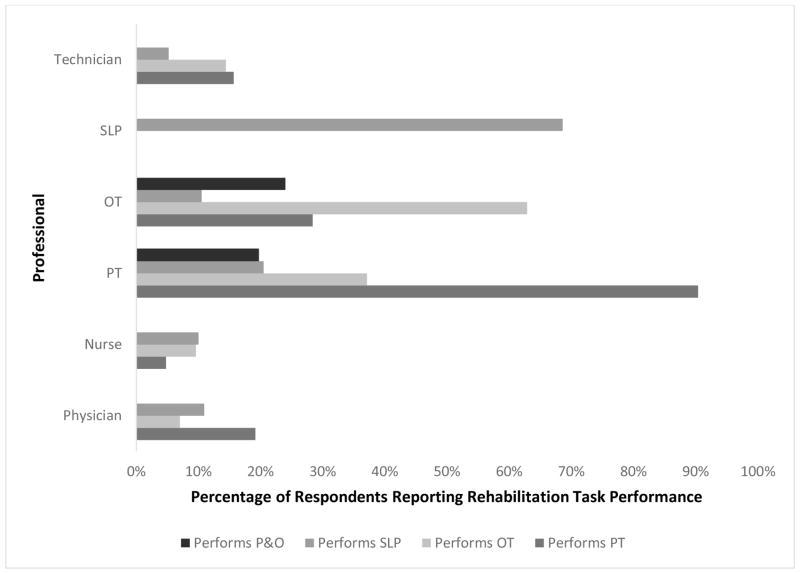

Performers of Rehabilitation Roles

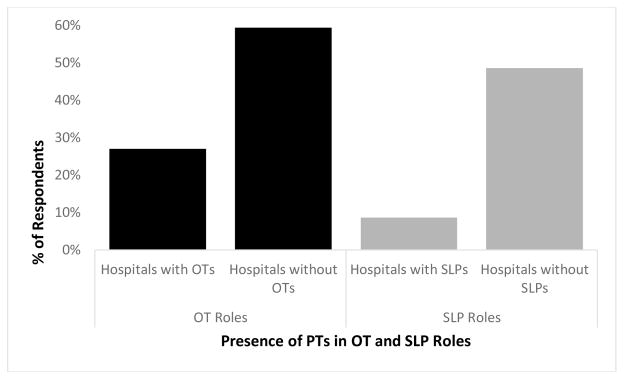

Figure 1 shows the reported performance of PT, OT, SLP, and P&O roles by the various rehabilitation providers. While OTs most frequently (64%) “helped patients adapt to complete their activities of daily living, work, and leisure,” participants reporting no OTs at their hospital most commonly (59%) said that PTs performed OT tasks (Figure 2). Similarly, SLPs were identified as performing SLP tasks by 70% of participants, but participants working at hospitals without SLPs most commonly (49%) reported that PTs performed SLP therapy (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Rehabilitation task distribution among professionals

PT=physical therapy/therapist; OT=occupational therapy/therapist; SLP=speech language pathology/pathologist; P&O=prosthetics & orthotics

Figure 2.

Physical therapists in OT and SLP roles

OT=occupational therapy/therapists; SLP=speech language pathology/pathologists

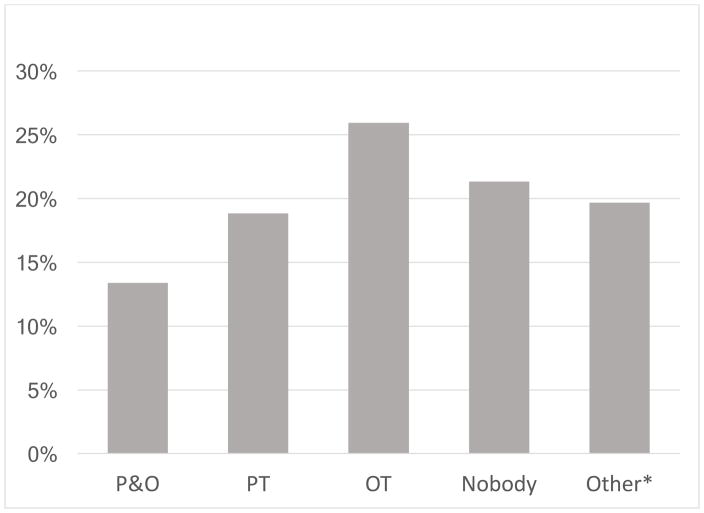

Fourteen percent of participants said the traditional Prosthetist-Orthotist (P&O) role is done by a P&O at their hospital, while 21% claimed that this role was not performed at all. Participants said that the prosthetist-orthotist role was otherwise performed by OTs (26%), PTs (19%), or “others” (20%), where physiatrists were the most common other professional specified, at 16% overall (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Performers of prosthetist-orthotist roles

OT=occupational therapist; PT=physical therapist; P&O=prosthetist-orthotist

*Note that the “Other” category is largely physiatrists (16% of total)

Table 3 shows the extent and types of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary collaboration reported at participants’ institutions.

Table 3.

Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary collaboration

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Do people providing different types of therapy sometimes treat the same patients? | ||

| Yes | 145 | 61 |

| No | 38 | 16 |

| I don’t know/blank | 56 | 23 |

|

| ||

| Do two or more providers work together to design a patient’s rehabilitation plan? | ||

| Yes | 104 | 44 |

| No | 107 | 45 |

| I don’t know/Blank | 28 | 12 |

|

| ||

| If so, how do they communicate? | ||

| Regular Meetings | 42 | 40 |

| Informal Conversations | 34 | 33 |

| Written Communication | 35 | 34 |

| Other + Blank | 4 | 3.8 |

|

| ||

| What is the frequency of regular meetings? | ||

| at least weekly | 15 | 36 |

| monthly | 22 | 52 |

| other+blank | 5 | 12 |

|

| ||

| Who attends these meetings? | ||

| Attending physician | 14 | 33 |

| Physiatrist | 23 | 55 |

| PT | 29 | 69 |

| OT | 23 | 55 |

| SLP | 20 | 48 |

| Nurse | 5 | 12 |

| Other | 5 | 12 |

| I don’t Know/Blank | 4 | 9.5 |

Health Service Delivery

One third of participants reported that patients waited fewer than 72 hours for inpatient therapy after referral, while another third reported that patients waited more than a week. Table 4 outlines the basis of rehabilitation referrals and barriers to rehabilitation identified by participants.

Table 4.

Rehabilitation referral bases and barriers

| Basis for Rehabilitaiton Referrals | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized clinical practice guide | 50 | 25 |

| Clinical judgment | 144 | 73 |

| Patient request | 36 | 18 |

| I don’t know | 12 | 6.1 |

| Other | 5 | 2.5 |

| Source of Standardized Clinical Practice Guide | ||

| Hospital Guide | 34 | 71 |

| National Guide | 7 | 15 |

| Institute/Society Guide from another country | 3 | 6.2 |

| Don’t know | 4 | 8.3 |

| Clinical Judge for Rehabilitation Referrals | ||

| Physiatrist | 56 | 28 |

| Treating physician | 121 | 61 |

| Nurse | 3 | 1.5 |

| Other | 2 | 1 |

| Patients Needing Rehabilitation that Actually Receive It | ||

| <25% | 23 | 10 |

| 25–50% | 44 | 19 |

| 50–75% | 68 | 30 |

| >75% | 72 | 31 |

| I don’t know+blank | 22 | 9.6 |

| Barriers to Inpatient Rehabilitation | ||

| Patient/Insurance Can’t Pay | 38 | 15 |

| Patient Rejects Rehabilitation | 12 | 4.6 |

| Delay in Referral Process | 137 | 53 |

| I don’t know | 32 | 12 |

| Other | 47 | 16 |

| Barriers to Outpatient Rehabiltation | ||

| Patient/Insurance Can’t Pay | 39 | 15 |

| Patient Rejects Rehabilitation | 6 | 2.4 |

| Distance/Patient Transportation | 106 | 42 |

| Referral Process Problem | 52 | 21 |

| I don’t know | 10 | 4.0 |

| Other | 39 | 15 |

Health Information Systems

Only reports of specialized rehabilitation professionals, who are presumably most familiar with the rehabilitation service, were considered for health information systems statistics. Just 28% reported that data were collected about rehabilitation service quality, with 63% of those reporting having seen changes in their institution in response to the data.

Essential Medical Products and Technologies (and other services)

Physical resources most frequently provided at participants’ hospitals included electrophysical agents like ultrasound (88%), a gym or other designated area for physical therapy (81%), mobility/gait aids (73%), and electromyography (76%).

The resources least frequently identified were thickened liquids (19%), endoscopic and/or radiographic swallow evaluations like FEES and VFSS (24%), and cognitive training tools like planners and budgeting instruments (28%).

DISCUSSION

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to assess rehabilitation infrastructure in Peru and also represents a preliminary effort to evaluate an urban rehabilitation system in terms of WHO Health System Building Blocks.

Health Workforce and Essential Medical Products & Technologies

Most personnel surveyed were PTs and physiatrists, which is consistent with participants’ reports that these staff were the most abundant rehabilitation professionals in Peru. Congruently, traditional PT tools like electrophysical agents, gyms, gait aids, and electromyography were the most frequently provided.

Inadequate data limit comparability of personnel numbers between Peru and other LMICs, and evaluating the rehabilitation workforce in other LMICs is a target for future research. However, other LMIC studies also suggest likely rehabilitation personnel deficiencies. A 2007 report from Ghana cited no physiatrists or OTs in the entire country and few PTs, SLPs, and P&Os.8 Meanwhile a 2011 article from Pakistan reported 38 physiatrists and approximately 1000 PTs and 150 OTs.9

The relative deficiency of SLPs (and the materials they use) and P&Os in participants’ hospitals is also consistent with findings from a 2006 report assessing rehabilitation services in four LMICs.7 However, our results reveal that in the many cases where these professionals are lacking, their roles are carried out by others. For example, PTs frequently carry out traditional SLP roles, while OTs and physicians provide some P&O services. Thus, a considerable extent of task sharing is being practiced, whether planned or unplanned.

Task sharing, the redistribution of tasks to existing or new cadres with either less training or narrowly tailored training, has proven a viable policy option in various LMIC settings.17–20 One of many examples is presented in an RCT among patients living with HIV/AIDS in Kenya, which yielded no significant differences between those receiving physician-driven versus non-physician community health worker-driven antiretroviral therapy care.18 Since rehabilitation is often necessary over the long term and in a community based setting,1 task sharing may prove ideal, or even essential, to augment the health workforce to adequately address the existing global burden of disability. Further research is warranted to determine feasibility and impact of task sharing in rehabilitation.

Similar to previous studies in LMICs, there is little specialized rehabilitative nursing, which is instrumental in the coordinated care of the stroke patient.7,21 Nurses were infrequently reported as having the authority to refer patients for rehabilitation services. The role of nurses in rehabilitation should be further examined, as task sharing among staff in nursing and rehabilitation care delivery may be one means to address existing healthcare workforce insufficiencies. Examining and formalizing task sharing as well as further assessing training capacity for specialized rehabilitation personnel are among our ideas for future research, which are detailed in Appendix 3.

Studies have shown that interdisciplinary stroke care is feasible in LMICs and results in better outcomes.22 In our study, about two thirds of participants indicated that different types of providers treated the same patients. However, only 44% indicated the presence of interdisciplinary collaboration in designing a patient’s rehabilitation plan, suggesting that this is another area for rehabilitation optimization in Peru.

Our results suggest that rehabilitation in Peru is focused on outpatient services. These findings may be partly due to the in-person sampling strategy employed for half of the data collected; it was physically centered around rehabilitation staff offices, which are often in outpatient areas. However, given that much of hospital-based rehabilitation is done within the outpatient department and that one third of participants reported that it took more than a week for patients to receive inpatient rehabilitation once it was ordered, it is probable that there is some deficiency in inpatient rehabilitation provision.

Health Services

“Referral process problems” were identified by 50% of participants to be responsible for delays in inpatient rehabilitation. Minimizing these delays is crucial for patient outcomes. Early mobilization through rehabilitation reduces the risk of atelectasis, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and contractures, and increases the likelihood patients will return to walking without assistance.21,23,24 Promoting early access to these services would thus lessen the burden of disability in Peru. It may be useful to examine the hospital and national rehabilitation referral guides that participants cited in order to identify any delays inherent in these policies.

Health Information Systems

Only 28% of specialized rehabilitation professionals said that data about the quality of the rehabilitation service were collected, which may represent an overall deficiency of rehabilitation service data collection or be secondary to a generally underdeveloped medical records system. This is consistent with existing studies showing that registries on patients with conditions requiring rehabilitation, such as trauma, traumatic brain injury, and spinal cord injury, are largely lacking or of poor quality in LMICs.25

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. It is possible that low rates of participation in the online survey increased the risk of bias. On the other hand, the online survey responders may have been more cooperative than non-responders and better able to respond to the survey questions. Regardless, because of the low online response rate, data are primarily from large public hospitals in urban Peru; they thus do not reflect the situation of the entire country or of smaller health centers. The minimal diversity in hospital type also prevented effective comparison between public and private and rural and urban areas, and the percentages reported may be biased by size and hence number of respondents from each specific institution,

Further, while physiatry and physical therapy and their corresponding equipment appear to be relatively more available compared to other specialized rehabilitation services, this could reflect lack of awareness of survey subjects (who were largely physicians and PTs) about the services besides their own. These services’ absolute adequacy was not assessable, as necessary numbers of personnel would be reasonably expected to depend on hospital services and size of the patient population served, neither of which was recorded by our instrument; moreover, to our knowledge, no needs- or evidence-based targets regarding the number of various rehabilitation personnel across settings or conditions exist.26

Additionally, the data were largely based on self-perceived reports rather than objectively collected data. Though our survey was done on an individual level, it included a few institutional-level questions (e.g. size of hospital, number of specialized rehabilitation personnel and services) that would have been more accurately answered by senior management/hospital administration staff rather than our rehabilitation workforce subjects. Similarly, because we chose a survey of clinical personnel, we have only addressed four of the six WHO building blocks. Further research is necessary to complete the description of rehabilitation infrastructure in Peru by assessing the remaining WHO building blocks: Leadership and Governance, and Finance.

CONCLUSIONS

This study assesses rehabilitation infrastructure in Peru and is a preliminary effort to evaluate a rehabilitation system in terms of WHO Health System Building Blocks. Recommendations for next steps for rehabilitation research in these areas are detailed in Appendix 3. Outpatient rehabilitation services in Lima are consistently available at the health centers included, and sufficient PTs and physiatrists are present at most facilities. Financial barriers are rarely cited as barriers to accessing services. However, there appear to be shortages of inpatient rehabilitation; few specialized rehabilitation services like speech language pathology, prosthetics and orthotics, and rehabilitative nursing; and little interdisciplinary collaboration among rehabilitation providers.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by NIH Research Training Grant # R25 TW009345 funded by the Fogarty International Center, the NIH Office of the Director Office of AIDS research, the NIH Office of the Director Office of Research on Women's Health, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- PT

physical therapy/therapist

- OT

occupational therapy/therapist

- SLP

speech language pathology/pathologist

- P&O

prosthetics & orthotics

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- WHO

World Health Organization

- LMIC

low or middle-income country

- PWD

persons with disability

Appendix 1. English survey

Appendix 2. Spanish survey

Appendix 3. High priority next steps for rehabilitation research in Peru

Health Workforce

|

Health Service Delivery

|

Health Information Systems

|

Essential Medical Products and Technologies

|

Footnotes

This manuscript was presented as a poster at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine 93rd Annual Conference, “Progress in Rehabilitation Research,” Chicago, IL, October 30–November 4, 2016.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World report on disability. Lancet. 2011;377(9782):1977. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocha J, Castro N. The epidemiology of moderate and severe injuries in a Nicaraguan community: A household-based survey. 2006:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-de-araujo R. Persons With Disabilities as an Unrecognized Health Disparity Population. 2015;105:198–206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I, et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. 2016:3–18. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosselin RA, Spiegel DA, Zirkle LG. Editorials Injuries: the neglected burden in developing countries. 2009:2–3. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.052290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta N, Castillo-laborde C, Landry MD. Health-related rehabilitation services: assessing the global supply of and need for human resources. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mock C, Nguyen S, Quansah R, Arreola-Risa C, Viradia R, Joshipura M. Evaluation of trauma care capabilities in four countries using the WHO-IATSIC Guidelines for Essential Trauma Care. World J Surg. 2006;30(6):946–956. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0768-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tinney MJ, Chiodo A, Haig A, Wiredu E. Medical rehabilitation in Ghana. 2007;29(June):921–927. doi: 10.1080/09638280701240482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rathore FA, New PW, Iftikhar A. A Report on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine in Pakistan: Past, Present, and Future Directions. YAPMR. 2011;92(1):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinchey JA, Shephard T, Furie K, Smith D, Wang D, Tonn S. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2005;36(9):1972–1976. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177529.86868.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schurr MJ, Ebner KA, Maser AL, Sperling KB, Helgerson RB, Harms B. Formal swallowing evaluation and therapy after traumatic brain injury improves dysphagia outcomes. J Trauma. 1999;46(5):813–817. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199905000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organization WH. Guidelines for Essential Trauma Care. Int Soc Surg Soc Int Chir Int Assoc Surg TRAUMA Surg INTENSIVE CARE. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miranda JJ, López-Rivera LA, Quistberg DA, et al. Epidemiology of road traffic incidents in Peru 1973–2008: Incidence, mortality, and fatality. PLoS One. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferri CP, Schoenborn C, Kalra L, et al. Prevalence of stroke and related burden among older people living in Latin America, India and China. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(10):1074–1082. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.234153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abanto C, Ton TGN, Tirschwell DL, Montano S. Predictors of Functional Outcome Among Stroke Patients in Lima, Peru. J Stroke Cerebrovas. 2014;22(7):1156–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.11.021.Predictors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Who. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and their Measurement Strategies. 2010:1–92. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulton B, Scheffler R, Sparkes S, Auh E, Vujicic M, Soucat A. Health workforce skill mix and task shifting in low income countries: a review of recent evidence. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selke HM, Kimaiyo S, Sidle JE, et al. Task-shifting of antiretroviral delivery from health care workers to persons living with HIV/AIDS: clinical outcomes of a community-based program in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(4):483–490. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181eb5edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lekoubou A, Awah P, Fezeu L, Sobngwi E, Kengne AP. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus and task shifting in their management in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(2):353–363. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooke-Sumner C, Petersen I, Asher L, Mall S, Egbe CO, Lund C. Systematic review of feasibility and acceptability of psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia in low and middle income countries. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:19. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0400-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Summers D, Leonard A, Wentworth D, et al. Comprehensive overview of nursing and interdisciplinary care of the acute ischemic stroke patient: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2911–2944. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L, de VSZK, VCB Does multidisciplinary stroke care improve outcome in a secondary-level hospital in South Africa? Int J Stroke. 2009;4(2):89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00254.x. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed9&NEWS=N&AN=2009211313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cifu DX, Stewart DG. Factors affecting functional outcome after stroke: A critical review of rehabilitation interventions. 1999;80(May):S35–S39. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Wijk R, Cumming T, Churilov L, Donnan G, Bernhardt J. An early mobilization protocol successfully delivers more and earlier therapy to acute stroke patients: further results from phase II of AVERT. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26(1):20–26. doi: 10.1177/1545968311407779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubiano AM, Carney N, Chesnut R, Puyana JC. Global neurotrauma research challenges and opportunities. Nature. 2015;527(7578):S193–S197. doi: 10.1038/nature16035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landry MD, Ricketts TC, Verrier MC. Human Resources for Health The precarious supply of physical therapists across Canada: exploring national trends in health human resources (1991 to 2005) 2007;6:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]