Abstract

Objectives

Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is the commonest manifestation of systemic sclerosis (SSc). RP is an episodic phenomenon, not easily assessed in the clinic, leading to reliance on self-report. A thorough understanding of the patient experience of SSc-RP is essential to ensuring patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments capture domains important to the target patient population. We report the findings of an international qualitative research study investigating the patient experience of SSc-RP.

Methods

Focus groups (FGs) of SSc patients were conducted across 3 scleroderma centers in the US and UK, using a topic guide and a priori purposive sampling framework devised by qualitative researchers, SSc patients and SSc experts. FGs were audio recorded, transcribed, anonymised and analysed using inductive thematic analysis. FGs were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved.

Results

Forty SSc patients participated in 6 focus groups conducted in Bath (UK), New Orleans (US) and Pittsburgh (US). Seven major themes were identified that encapsulate the patient experience of SSc-RP: physical symptoms, emotional impact, triggers & exacerbating factors, constant vigilance & self-management, impact on daily life, uncertainty and adaptation. The inter-relationship of the 7 constituent themes can be arranged within a conceptual map of SSc-RP.

Conclusion

We have explored the patient experience of SSc-RP in a diverse and representative SSc cohort and identified a complex interplay of experiences that result in significant impact. Work to develop a novel PRO instrument for assessing the severity and impact of SSc-RP, comprising domains/items grounded in the patient experiences of SSc-RP identified in this study is underway.

Key Indexing Terms: Systemic Sclerosis, Scleroderma, Raynaud’s Phenomenon, Qualitative Research, Patient participation, Patient Reported Outcomes

The term Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is generally used to describe episodic acral vasospasm manifesting as digital discolouration and pain (1). The majority of people experiencing RP symptoms have primary RP; a syndrome of benign but intrusive exaggerated digital microvascular responses to cold and/or emotional stress, affecting approximately 5% of the healthy population (1, 2). The term secondary RP is applied when the symptoms are the consequence of underlying pathology; an important cause being autoimmune rheumatic diseases such as systemic sclerosis (SSc), in which functional vascular disturbances are compounded by a progressive obliterative microangiopathy (1). RP is the commonest disease-specific manifestation of SSc affecting ~96% of patients (3). SSc-RP is consistently ranked highest in patient surveys exploring the frequency and impact of disease-related complications of SSc (4, 5). RP is an episodic phenomenon, not easily assessed in the clinic setting, leading to a reliance on patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments. The patient perspective captured by PRO instruments provides valuable insight into the patient condition, not always captured by clinician-reported assessment tools (6). However, no studies to date have explored the domains that form the patient perspective of SSc-RP; yet a thorough understanding of the patient experience of SSc-RP is essential if PRO instruments assessing the severity and impact of SSc-RP are to fully capture experiences important to patients (7). The aim of the present study was to fully explore the themes and subthemes that comprise the patient experience of SSc-RP.

Patients & Methods

Study management

The study development and conduct was overseen by a steering committee comprising 9 SSc experts (JDP, RTD, LAS, TMF, NJM, AH, MMC, FI and DK), 2 patient research partners (JW and HJ), a vasculitis expert with experience in PRO instrument development (JR) and an experienced team of qualitative researchers (CA, ED and SH). Ethical approval was obtained from independent ethics committees by chief investigators at each patient-participating site (JDP, RTD and LAS respectively) with all participants providing informed consent before taking part.

Study design

An international multicentre qualitative research study comprising patient focus groups (FGs) in Bath (United Kingdom), Pittsburgh (United States of America) and New Orleans (United States of America) was developed to ensure experiences were sought from a broad geographical, cultural and ethnic cross-section of patients. Focus group (FG) meetings enable open discussion and debate amongst participants; allowing convergent and divergent views to be clarified where necessary during the discussion (8). The dynamic nature of focus group interactions facilitates capture of patient experiences not always expressed in 1:1 interview settings.

Participants

All patients fulfilled the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for SSc (9), were aged over 18 years, had sufficient English language skills to participate in group discussions and capacity to provide informed consent. Enrolment decisions were based on an a priori purposive sampling framework developed by the project steering committee and designed to ensure a representative patient cohort with respect to disease subtype (aiming for 60:40% split between limited and diffuse cutaneous SSc), disease duration with early and established disease (≤3 and >3 years since first non-RP symptom), history of digital ulcer disease (as a proxy for peripheral vascular disease severity, aiming for approximately 50:50% split to be representative of digital ulcer prevalence in SSc), gender (aiming for 5:1 female predominance) and ethnicity (with Caucasian, African-American and Hispanic representation). A clinician case-report form facilitated subsequent participant selection against the requirements of the purposive sampling framework (10). The size of each FG was limited to a maximum of 9 participants to ensure all participants had the opportunity to express their personal views and could confidently challenge alternative/opposing experiences expressed within the group. A minimum of three FGs was originally planned with an intention to undertake additional FGs until ‘thematic saturation’ was achieved (11).

Data collection

Each FG lasted approximately one hour, was co-facilitated by JDP and at least 1 other member of the steering committee and was audio-recorded, transcribed and anonymised. An initial topic guide was developed by the steering committee (see supplementary material), with each FG commencing with broad open questions enquiring how patients would describe their RP experiences, before progressing to more focussed discussions, sometimes targeting incompletely explored emergent themes from earlier FGs, ensuring thematic saturation was achieved. At each FG, efforts were made to create a relaxed open environment in which the sharing of individual (and shared) experiences was encouraged and everybody’s opinion respected.

Data analysis

Qualitative analysis of the FG transcripts was undertaken by experienced qualitative researchers (SH, ED and CA). Inductive thematic analysis was adopted to ensure the findings were grounded in shared patient experiences rather than imposed from existing concepts (12). In the first stage, qualitative data were coded by reading the anonymised transcript multiple times; making notes of words and short phrases that captured important experiences. Units of meaning were identified and given descriptive labels (codes). In the second stage, the codes from the transcript were reduced (removing duplications and merging overlapping codes) and explored to see how conceptually-related codes could be grouped to form subthemes, and finally subthemes were grouped to form overarching themes (12). The themes were then independently and systematically applied to each transcript by other team members to ensure a rigorous analysis and minimise researcher bias (with amendments made if new codes emerged). This process was an iterative one, undertaken concurrently with data collection, allowing emerging themes to be explored and/or challenged in subsequent groups. After a preliminary independent analysis of the data, an analysis de-briefing meeting was convened attended by the qualitative research team (SH, CA and ED), SSc patient research partners (JW and HJ), an experienced PRO developer (JR) and SSc expert (JDP) to derive consensus on the theme groupings (and applicable subthemes) and the conceptual map describing the inter-relationship of the respective themes.

Results

Forty SSc patients participated in 6 focus groups conducted in Bath, UK (n=2), New Orleans, US (n=3) and Pittsburgh, US (n=1). The a priori purposive sampling framework ensured broad and representative participation in terms of clinical phenotype, age, gender and disease duration. The multicentre design ensured diverse geographic, cultural and ethnic participation (Table 1). The composition of individual groups differed as deliberate efforts were made to include “missing cases” in the latter focus groups. A 7th planned FG in Bath was cancelled as thematic saturation had been achieved.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical phenotype of enrolled participants according to purposive sampling framework

| Demographics and clinical feature of enrolled patients presented according to purposive sampling framework |

Bath | Pittsburgh | New Orleans |

Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Number of participants, n (n per focus group held) | 17 (8,9) | 6 (6) | 17 (7,7,3) | 40 |

|

| ||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 62.5 (11.5) | 50.8 (17.7) | 52.7 (12) | 56.6 (13.4) |

|

| ||||

| Mean disease duration*, years (SD) | 13.8 (11.3) | 8.8 (6.6) | 7.7 (6.3) | 10.5 (9.1) |

|

| ||||

| Disease subtype, n (%): | ||||

| Limited cutaneous SSc | 15 (88) | 5 (83) | 4 (24) | 24 (60) |

| Diffuse cutaneous SSc | 2 (12) | 1 (17) | 13 (76) | 16 (40) |

|

| ||||

| Disease duration*, n (%): | ||||

| ≤3 years | 2 (12) | 2 (33) | 5 (29) | 9 (23) |

| >3 years | 15 (88) | 4 (67) | 12 (71) | 31 (77) |

|

| ||||

| Gender, n (%): | ||||

| Female | 16 (94) | 5 (83) | 13 (76) | 34 (85) |

| Male | 1 (6) | 1 (17) | 4 (24) | 6 (15) |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity, n (%): | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 17 (100) | 6 (100) | 3 (18) | 26 (65) |

| Black/African-American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (71) | 12 (30) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 2 (5) |

|

| ||||

| Vasodilator medication use‡, n (%): | ||||

| Nil | 3 (18) | 2 (33) | 2 (12) | 7 (18) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 9 (54) | 2 (33) | 14 (82) | 25 (63) |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitor | 5 (29) | 4 (67) | 3 (18) | 12 (30) |

| Prostanoids | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Angiotensin II antagonists | 4 (24) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| Endothelin receptor antagonist | 1 (6) | 1 (17) | 2 (12) | 4 (10) |

| Combination therapy | 3 (18) | 3 (50) | 3 (18) | 9 (23) |

|

| ||||

| History of digital ulcer disease, n (%): | ||||

| Yes | 7 (41) | 4 (33) | 12 (71) | 23 (58) |

| No | 10 (59) | 2 (67) | 5 (29) | 17 (42) |

Indication not specified and includes SSc-RP, SSc-DU, SSc-PAH and/or systemic hypertension/cardiovascular risk

Since first non-Raynaud’s symptom

SSc, systemic sclerosis; DU, digital ulcer; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension

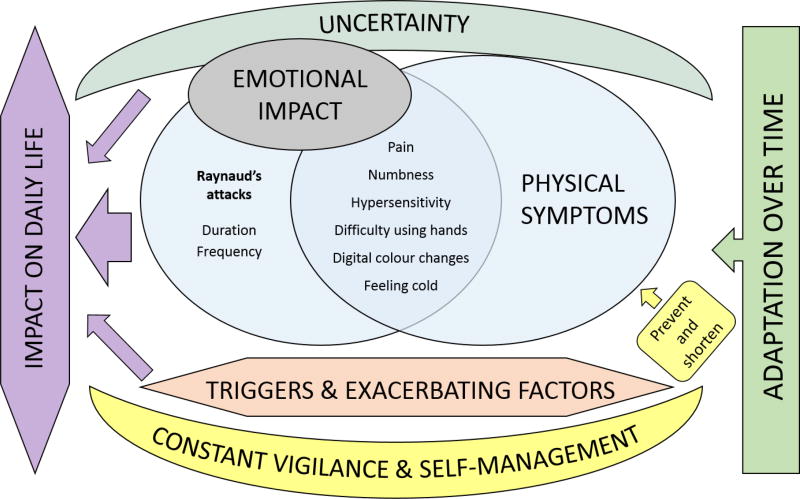

Seven major themes emerged, that together constitute the patient experience of SSc-RP: (i) Physical Symptoms, (ii) Emotional Impact, (iii) Triggers & Exacerbating Factors, (iv) Constant Vigilance & Self-management, (v) Impact on Daily Life, (vi) Uncertainty and (vii) Adaptation. The inter-relationship between the 7 constituent themes can be arranged within a conceptual map of the patient experience of SSc-RP (Figure 1). Each theme (and subtheme) shall be described.

Figure 1.

A conceptual map comprising the 7 major inter-related themes that constitute the patient experience of SSc-RP

Theme 1: Physical symptoms

The physical symptoms of SSc-RP differed between participants (Table 2). For some, pain was the predominant sensation (Q1–2), whereas others described the predominant symptoms as numbness and/or tingling (Q3–4) or even burning/stinging/hypersensitivity (Q5–6). Many patients reported a combination of symptoms (Q7), sometimes evolving as episodes of digital ischaemia develop and abate. Patients are aware that their peripheries are cold to touch and many patients associate physical symptoms of pain and numbness as “feeling cold” (Q8–9). A combination of pain and altered tactile sensation result in difficulty using the hands (Q10–11), particularly concerning fine motor function (Q10) which can be further impaired by the need to wear gloves (Q60). The oft-cited “red, white and blue” digital colour changes of SSc-RP were described, as expected, but patients preferentially adopted other terms such as purple (Q13 and Q15), marbling (Q12) and black to report the cutaneous discolouration of SSc-RP (Q7 and Q14). The fingers are the predominant body site considered by patients when discussing SSc-RP, in part because the fingers are the most significantly affected area (Q15), but also owing to the importance of the fingers for activities of daily living and the fact that the fingers (unlike the toes, nose and lips) are typically exposed; both to the elements and the visible attention of the patient (Q16). Discolouration of the knees, not a body site usually associated with SSc-RP, was mentioned by more than one participant (Q15). Colour changes in the lips, nose and knees do not appear to result in the same sensory changes as the fingers and toes. For many participants, the notion of “attacks” was consistent with their experiences of SSc-RP but some expressed difficulty distinguishing “attacks” of SSc-RP as the following passage attests:

N2 S4: “I’m not really 100% sure what an ‘attack’ is because it’s just so cold and then they come back tingling. But I can’t say ‘Oh, I’ve got an attack’… I can’t say ‘Oh, they went white’, although they do change colour sometimes…I’ve just taken it for granted and lived with it.”

Table 2.

Quotes supporting the “Physical Symptoms” and “Emotional Impact” themes of the patient experience of SSc-RP

| Subtheme | Q | Subject | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical symptoms of SSc-RP | |||

|

| |||

| Pain | 1 | P1 S2: | How do I feel when it happens? Oh, my fingers start to hurt, they turn white, and it hurts not only on the surface but all the way down to the bone |

| 2 | P1 S5: | When you say the word Raynaud’s, I just think the word pain. | |

| Numbness/Tingling | 3 | B2 S1: | I have tingling at times but it’s the numbness and not being able to feel and touch I think is the main thing, really from the symptom point of view as opposed to what it looks like. |

| 4 | P1 S6: | They get very numb. It’s not exactly pain, it’s like that really, really deep numbness, like it almost hurts, but to me it’s not exactly the same as pain. | |

| Burning/hyper-sensitivity | 5 | N1 S4: | I think stinging, the stinging sensation that you feel whenever something like your leg falls asleep or something, I will get that sensation |

| 6 | N1 S6: | …they were so sensitive, so tender, the fingertips. I did have an office job so I did a lot of typing, and I actually could not … type like you normally type. | |

| 7 | B1 S6: | … a loss of sensation and then I get severe tingling, pain and then black hands, would be the quick way of describing it. | |

| Feeling cold | 8 | N1 S2: | I would describe it as your hands are extremely cold |

| 9 | B1 S3: | …my hands and my feet go like, well they’re like ice. I can’t even touch myself when I get a bad attack of it. I can’t put my hand on my arm, I’m so cold | |

| Difficulty using hands | 10 | B1 S2: | ..when the sensation kicks in you can’t, you can’t pick things up and you can’t knit or get the money out of your purse… |

| 11 | N3 S2: | When you’re going through a serious episode of Raynaud’s you’re hands are pretty much useless to you | |

| Colour changes | 12 | B1 S1: | In those days it was very much marbling. Now it is straight to the white. |

| 13 | B2 S5: | I find with myself if I get cold I get purple lips, my hands, my toes and even my knees go purple | |

| 14 | N2 S3: | But it was my, my, my fingers. They would be real, real, I mean black, numb. | |

| Body Sites | 15 | P1 S1: | I think of purple fingers. That’s usually how it manifests. I do get it in my toes a little bit, even knee caps will turn purple, but hands have always been the worst. |

| 16 | B1 S3: | And my lips at the same time like you said, you know, they’ve turned round and said my “lips have gone purple and blue, am I all right?” | |

| Duration of attacks | 17 | B1 S6: | It may take anything from five minutes to an hour to get the circulation back in |

| 18 | B2 S1: | ..other times if you’ve gone into a cold place I think that my fingers haven’t gone completely normal all afternoon really. | |

| Frequency of attacks | 19 | P1 S1: | I probably have maybe a handful of days a year where I don’t have any attacks, but it’s always got to be in the summer and it kind of has to be the perfect conditions |

|

| |||

| Emotional Impact of SSc-RP | |||

|

| |||

| Distress | 20 | B2 S8: | ….last time when I went shopping…I couldn’t open the boot of my car to put the shopping in. I had to ask the lady in the next car to me to do it and when I got in the car I just started crying. I couldn’t take it. |

| Annoyance | 21 | P1 S4: | …by the time I got to checkout I couldn’t pull my charge card out of my wallet because I had no feeling then. And it’s just … All the time I’m in there … I just think I can’t wait ‘til I get back outside, I can’t wait ‘til I get to my car, I can’t wait ‘til my fingers are warm again. |

| 22 | B2 S4: | For me it’s the frustration of not being able to do what I want to do while you’ve got an attack, because … you can’t move your hands, and you can’t do anything and I think that’s even worse than the pain. | |

| 23 | B1 S1: | Things like when you do go out, try to do your shopping, drop a coin and realise you cannot get it up again. You can no longer close your purse which you’ve opened to get your money out, and silly little things like that. And you sometimes get so frustrated, tears come to your eyes with it. | |

| Despair | 24 | N3 S2: | …once it [SSc-RP] sets in the pain could be, oh, just so miserable, I mean, just absolutely intolerable…. Oh, [I] could go into hysterics it can get that bad….I’ve felt like I want these hands off of me. |

| Embarrassment | 25 | P1 S1: | It’s like you’re at work and you’re going in for a performance review and you want to look your best and be confident, but your hands are purple, and it’s because of the stress of the situation and you feel stupid. It’s not really like the life or death …but it still does have some effect on you. |

| 26 | B2 S1: | ..my hands were that bad the signature didn’t look anything like my signature and she [shop keeper] embarrassed me, she called the manager over, they wouldn’t let me have my shopping and I walked out the shop in tears | |

| 27 | P1 S6: | ..people make fun of me a lot at work…It’s a silly thing, but like it’s annoying. I’d rather not have attention for that reason. | |

| 28 | N3 S3: | …but keeping the gloves and wearing the gloves in summer time used to bother me because people stared at me, people laughed at me, and that was embarrassing. | |

Q refers to the numbered quote cited in the text. P1 denotes Pittsburgh, group 1; N1, N2, N3 denotes New Orleans groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively; B1, B2 denotes Bath groups 1 and 2; S# denotes subject (participant) number within each focus group.

The duration of SSc-RP attacks differed between individuals and varied within individual patients according to exposure to cold and the capacity of patients to either take positive steps to warm their hands or extract themselves from an environment conducive to SSc-RP symptoms (Q17–18). The frequency of SSc-RP attacks was also largely dependent on exposure to exacerbating triggers but the majority reported attacks occurring several times per day and seldom experienced days completely free of SSc-RP symptoms (Q19).

Theme 2: Emotional impact of SSc-RP

Experiences of SSc-RP have a significant emotional impact on patients encompassing feelings of distress (Q20), annoyance (Q21–23) and, for some, desperation (Q24) (Table 2). Loss of normality and the restrictive nature of SSc-RP on social participation and leisure pursuits is a particular source of frustration. For some, emotional distress resulted in irritability that impacts on relationships (see later). Unwanted attention towards cutaneous discolouration, the need to wear extra clothing/gloves in ambient conditions and difficulty using hands due to SSc-RP, was highlighted as a source of embarrassment, particularly in the workplace and/or public places (Q25–28). Actual body image dissatisfaction related to the visible discolouration of SSc-RP was not a common theme and many patients had come to accept the appearance of SSc-RP (Q42, see later).

Theme 3: Triggers and exacerbating factors

Cold exposure was the principal exacerbating factor for all participants (Table 3). Defining a temperature threshold at which RP attacks were more likely was volunteered by some participants (Q29), whereas for most it was a change (typically a reduction) in temperature or draught that was most likely to precipitate SSc-RP symptoms (Q30–31). Exposure to domestic refrigeration appliances (Q32–34) and air conditioning were very frequent exacerbating factors, with visits to the grocery store being particularly likely to trigger SSc-RP symptoms (Q32–34), perhaps owing to less easily mitigated sporadic fluctuations in temperature that grocery shopping results in. For many, emotional stress was an important trigger (Q35–36), sometimes exacerbated by feelings of embarrassment caused by digital discolouration (Q25), and some patients reported their SSc-RP symptoms were less intrusive and more manageable when they felt relaxed (Q37). For others, and in contrast to cold exposure, stress had no discernible impact on their SSc-RP (Q38). Some participants reported a high level of unpredictability, with SSc-RP attacks occurring for no apparent reason (Q39). Rarely reported exacerbating factors included gripping tightly and passive smoke inhalation.

Table 3.

Quotations supporting the “Triggers & Exacerbating factors” and “Constant Vigilance & Self-Management” themes of the patient experience of SSc-RP

| Subtheme | Q | Subject | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triggers & Exacerbating factors of SSc-RP | |||

|

| |||

| Cold | 29 | N1 S4: | Now er, the medication has helped to the point of where … I can handle temperatures down to about around 50 [°F] or so. If it’s 50 or below I will have issues when I go outside into the cold. |

| 30 | B2 S4: | Even the tiniest draught and that’s me gone even if it’s blazing sunshine and I’ve got a draught . It’s the regulation of the body temperature…it just can’t cope with change. | |

| 31 | P1 S2: | …it would be 90 something degrees [°F]. You come out, you’re in the sun, and a breeze goes by, and right away your hands start turning colours | |

| 32 | N1 S7 | But, when I go into a situation of a grocery store when you go by the freezer section, you know, I can tell, I start turning purple, my fingers start turning purple. | |

| 33 | P1 S1: | The meat department or anything that’s refrigerated. A lot of it is … It almost feels like you’re helpless when you’re trying to warm them up, but you don’t really know if it’s going to work or not. | |

| 34 | N2 S7: | .and every time I would go in a grocery store around the freezer part I could not … I mean the minute I’d get to there …[voices murmur agreement]. It would actually turn so black. | |

| Stress | 35 | B2 S6: | My hands don’t necessarily have to be cold, I can be in a situation like this, just nerves can make mine go. |

| 36 | B2 S5: | Yes, stress, very much if you’re put in a stressed environment then that will bring the purpleness (sic) on the fingers | |

| 37 | N2 S5: | I don’t know how much … is like psychological or not, but I know that when I’m feeling more relaxed I, physically, I feel as though I’m doing better. But when I’m stressed for whatever reason like, it’s harder to manager to my symptoms. | |

| 38 | N3 S3: | I haven’t noticed it, maybe it could be something I’m not aware of, stress bringing on the condition | |

| Unpredictability | 39 | N1 S6: | And I’ll get attacks and it’s like I’m not cold, what is causing me to have a Raynaud’s attack? And like I’m totally not cold, it’s hot, it’s in the summer, so that, I don’t know what sets that off, I really don’t. |

|

| |||

| Constant Vigilance & Self-Management | |||

|

| |||

| Maintaining warmth (preventative measure) | 40 | B1 S6: | And then if I know that I’m going to be outside shooting then I make sure I’ve got, you know, hot pads and gloves and everything else, so you just kind of adapt to it really. |

| 41 | B2 S7: | I have the heating on day and night and I’ve always got a thick coat and gloves and then I sort of forget about it really, I’ve done all I think I can do. | |

| 42 | P1 S2: | I have mittens all over my house. I have great friends who knit me mittens and so I go to the grocery store with mittens on. People look at me like I’m really dumb, but that’s life. Who cares if they think I’m dumb wearing mittens, but they work. | |

| 43 | P1 S1: | The first 5–10 years [were] really rough, and I was stubborn. I just wanted to wear a t-shirt and a jacket and some gloves, and you have to accept, no, I need to have a t-shirt, a longer shirt and a hoodie and a jacket and mittens, and everyone else is wearing some lighter clothes and I’m there totally bundled up, but at this point that’s kind of just my daily life, so I think it’s actually gotten easier over time. | |

| Seeking warmth (alleviating measure) | 44 | N3 S2: | If it sets in just putting a glove on, putting gloves on, just won’t do it….I have to put heat to my hands somehow with something, to apply heat to get that pain to go away. |

| 45 | P1 S1: | Like everyone’s said they’ll pretty much stay that colour until I do something; run them under hot water or put some gloves on or put a jacket on, especially in the grocery store, I notice that all the time. | |

| 46 | N3 S1: | Oh no, you’d have to do something in order to warm them up, and you can’t just, like when your fingers or hands go numb, you shake them out, it’s not a shake it out kind of scenario, it’s a ‘I got to do something.’ | |

| 47 | B1 S5: | Well one thing that is quite easy I find is a wash basin of warm water, you know, in an emergency if you’ve obviously got nothing else…..It comes back you know, all right I find. | |

| Avoiding cold | 48 | B1 S4: | I tend not to leave the house if I don’t have to in the winter |

| 49 | P1 S6: | My brother lives in xx and I just won’t visit him unless it’s like the height of summer because it’s freezing up there and there’s nothing I can do to get warm enough so I just don’t go there. | |

| 50 | P1 S4: | I don’t ski anymore, either…’cos you’re taking your gloves off, if your ski falls off or whatever, so even if you have something in your gloves to keep them warm, no, so I avoid winter activities, let’s put it that way. | |

| Limited effectiveness of self-management | 51 | B1 S2: | I had three pairs of gloves on the other day and I’d still got cold hands |

| 52 | P1 S3: | I think I could possibly prevent attacks all day, but nobody would be able to live with me [if I maintained] the house at 90 degrees [°F]. (laughter) | |

| 53 | B2 S5: | I find that there’s nothing you can do to stop the attack because with me there’s no tell-tale sign, there’s no tingling, it’s just I’m here and you’re gonna (sic) have to deal with it, whether it takes ten minutes, twenty minutes it is as long as it lasts. | |

| 54 | P1 S2: | I can’t prevent them, but as soon as they [SSc-RP symptoms] start I try to do something about it, try to warm them up | |

| 55 | B2 S4: | The best thing is to get out the environment that’s causing it but you can’t always do that, you know so at that stage there is no hope. | |

Q refers to the numbered quote cited in the text. P1 denotes Pittsburgh, group 1; N1, N2, N3 denotes New Orleans groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively; B1, B2 denotes Bath groups 1 and 2; S# denotes subject (participant) number within each focus group.

Theme 4: Constant vigilance & self-management

Patients described a life of constant vigilance and self-management that, for patients, means that nothing is simple anymore and everything must be planned and prepared for. All patients reported taking positive steps to maintain warmth to prevent and/or reduce the impact of SSc-RP (Q40–42, Table 3) and patients reported such behaviour helping them manage their symptoms better as time had progressed (Q43). Abating attacks of SSc-RP necessitates the application of local warmth and many patients reported strategies they had adopted to achieve this such as using heat packs, submerging in basin of warm water etc. (Q44–47). Patients with SSc make significant sacrifices to avoid cold exposure that, whilst helpful, negatively influence social participation, relationships and leisure activities (Q48–50). Despite the adoption of such measures, complete avoidance of SSc-RP symptoms was an unachievable goal and many participants accepted the limits of self-management (Q51–55).

Theme 5: Impact on daily life

Each of the preceding themes make their own specific contribution to the broader impact of SSc-RP on daily life (evident from a number of quotations provided in Tables 4 and 5). Specific aspects of daily life that are commonly affected include shopping (Q56), household chores (Q57–58) and self-care (Q59). The need to wear gloves the majority of time exacerbates the impaired functional capacity making everyday activities harder to complete (Q60). Participation and enjoyment in social and leisure activities are either directly affected by SSc-RP symptoms (Q61–64) or lead to trade-offs taken to avoid cold exposure (Q50). Participants provided examples when work participation was challenging because of an inability to control their work environment to suit their needs (Q65). An inability to complete work tasks due to SSc-RP was a source of guilt for some (Q66–67). Some reported negative experiences in the workplace from colleagues ignorant or unsympathetic to their needs (Q68) whilst other expressed concerns about the effect of SSc-RP on job security (Q69). Several examples were given of the impact of SSc-RP on family life, which included being irritable around family members (Q70–71), having difficulty fulfilling family roles (Q72–73) and a sense that family members don’t fully appreciate the extent of their problems (Q74). Many participants expressed sorrow relating to a loss of normality and inability to do things they took for granted previously (Q75).

Table 4.

Quotes supporting the “Impact on daily life” theme of the patient experience of SSc-RP

| Subtheme | Q | Subject | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of SSc-RP on daily life | |||

|

| |||

| Daily activities | 56 | B2 S1: | You can’t sort of feel things properly, trying to do shopping, trying to get cards out of your purse and things you can’t touch it, trying to sign your name when you didn’t have to do the push button for the cards |

| 57 | B2 S6: | I can’t even change the bed, I can’t take the sheets off the bed, I can’t put them back on the bed. Trying to put a pillow case on, especially because it’s cold you just can’t, your fingers just can’t do it, even though you’re willing them to do it, you just can’t do it. | |

| 58 | N1 S5: | Housework….The biggest problem was mopping the floors and sweeping the floors. It’s almost like I cannot get a grip of the … the, er, mop stick and the broom to actually sweep right, because I tend to close my hand real tight around it when it … That’s when it affects the most. | |

| 59 | B2 S9: | I say, and I say to him don’t put the toothpaste back tight, don’t put the washing up liquid back tight because I can’t click it to get the washing up liquid out…. I mean some things I can still undo with my teeth, but not jars. I haven’t got that big a mouth to do a jar, but little bottles, and water bottles I do with my teeth because I can’t undo them. | |

| 60 | B2 S1: | I think sometimes with the gloves …. it actually makes it more difficult anyway for holding. You know you wear the gloves to warm your hands up but then you can’t grip properly | |

| Social & Leisure | 61 | B2 S6: | I can’t walk my dogs…because I can’t hold the lead, I’m frightened that I’ll get so far and my fingers won’t be able to hold the lead once you get going. Even with the gloves on. |

| 62 | N2 S2: | I love going out to eat but when I go I bring the thickest coat and gloves that I can find and I’ll still be miserable. I can’t even really enjoy myself. I’ll be like, “I’ve got to get out of here. It’s so cold.” | |

| 63 | B1 S6: | I used to climb two or three times a week, and I had to stop that because it kept happening while I was climbing. I had a couple of quite nasty falls, so I had to stop that. And that was basically just loss of sensation when you’re clinging to a rock face. | |

| 64 | N1 S4: | … if it’s real cold, obviously, it does. It affects it [social life] severely, I mean, you know, you can’t … There’s certain hobbies like playing videogames, or maybe woodworking or things like that, where it just doesn’t. It just doesn’t work like it used to.. | |

| Work | 65 | B2 S6: | I work in a library and like you say with the air conditioning if I get under the air conditioning and suddenly go straight there, I’ve walked from a nice warm place out of the office into the library, smack straight away it goes. …you can’t move the books, you can’t get the book back in because your fingers just can’t physically move because it’s that sore. |

| 66 | B1 S4: | I felt really bad because I’d been there longer but there was staff coming in, I’m on more money than them, and I’m waiting for them to finish their job off for them to come and help me start my jobs. So I actually left last year. | |

| 67 | N1 S3: | Well, by the time I was sick, I was self-employed, I had started a little business of my own. But yes, it shut me down. It … I had to employ other people to do what I was doing, so yes. | |

| 68 | N3 S3: | I had a supervisor and I had to put gloves on and I learned to type in the gloves….She called me into her office and…she grabbed her phone and said “now I’ve got a picture”. I looked at her, she said, “huh, it’s not that cold, I can’t believe you have gloves on in here.”…And I’m like “okay, what did you call me for?” Because I had to learn to deal with people’s reactions… I had to just stop being embarrassed about that and just walk around and put your gloves on wherever you go, if they look, they laugh. | |

| 69 | B2 S5: | Well I just never told my employer….Because I wouldn’t have been able to do my work….I used to put three lots of thermal linings on in gloves and I used to freeze but I had to do it because that’s what my job was. | |

| INT: | So were you worried about telling your employers in case… | ||

| B2 S5: | Yes, because they would have said well don’t bother coming back Monday. | ||

| Family | 70 | P1 S5: | I feel very bad, because then I get angry, I get cranky with my family, my poor husband, you know, just because it’s hurting so bad and he’s never going … to understand that pain of just going into a grocery store |

| 71 | P1 S4: | especially if he’s [spouse] with me and I have episodes…I’m just, come on, I’m just very short with him or whatever…. if I’m alone I just deal with it, but sometimes I do tend to take it out on him maybe a little bit. | |

| 72 | B2 S9: | I used to take him up and give him a bath, and now he says, “No, not nanny, let mummy and daddy do it, not nanny, she’s too cold.” So I can’t bath him because my hands are too blue and they start as soon as I’m going up the stairs….So I don’t bath him anymore, it’s a shame. That’s a big thing to lose that is, yes. | |

| 73 | N3 S1: | I won’t ever show that to them because I’m supermomma (sic) but you know, when they’ve gone to school, I kind of think about it and, you know, it’s getting to the point I can’t even tie a shoestring. | |

| 74 | B1 S1: | My daughter is just laughing at me. She understands to a point but she doesn’t understand the pain and I think the frustration of it. | |

| Loss of normality | 75 | B2 S5: | ..it’s a combination of the pain and the numbness, the not being able to do normal things. It would be lovely to sort of turn the clock back and … be back to what I was like when I was 18, 19 [years old], go in the sea and not come out blue, sit in the garden after the sun goes down at 6 o’clock |

Q refers to the numbered quote cited in the text. P1 denotes Pittsburgh, group 1; N1, N2, N3 denotes New Orleans groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively; B1, B2 denotes Bath groups 1 and 2; S# denotes subject (participant) number within each focus group.

Table 5.

Quotes supporting themes of “Uncertainty” and “Adaptation” relating to the patient experience of SSc-RP

| Subtheme | Q | Subject | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | |||

|

| |||

| Consequences of SSc-RP (especially ulcers) | 76 | P1 S1: | ..if I knew there was not going to be any ulcers it [SSc-RP] probably wouldn’t bother me that much. |

| 77 | P1 S3: | Because I do worry about getting ulcers and that’s the whole name of the game. If it [SSc-RP] was just inconvenience and not perhaps long term damage then I wouldn’t probably care. I’d deal with it.. | |

| 78 | B2 S6: | I just fear, when I’ve got them and they’re coming very regularly, I just fear the ulcers, because I get ulcers | |

| 79 | B1 S5: | I think I worry whether the Raynaud’s is sort of connected with the general sort of aging process, which you know, we all have to accept as we get older. | |

| Efficacy of treatment | 80 | N1 S5: | What other treatments can we get, if one don’t work, what’s next? I mean, I’m on so much medication … I’m just confused on what … what’s working some days and what’s not working. |

| Uncertainty around changes in usual activity |

81 | P1 S3: | . It does concern me going on trips. If I get into a really cold room, and what’s going to happen. I just want to comfortable and be safe, that’s all. |

| 82 | N3 S3: | in my case I had a high level of anxiety because I was driving someone else’s car and the heater didn’t work, and it was cold outside that day, and within such a short span of time with the heater not working my hands begin to sort of numb up and I said I’m not going to be able to drive that far. So then I began to get stressed saying my car’s in the shop and if this thing’s cold I won’t be able to drive this car so that caused me stress. | |

| Anxiety | 83 | P1 S5: | it’s always … what kind of clothes? and who’s going to be with me?… So there’s a lot of anxiety that comes with it, and maybe that’s a lot of reasons I’m at home a lot, too. I don’t have to worry about it. |

| 84 | N3 S1: | I do believe that anxiety is associated with Raynaud’s …. you have to always be aware of something that may affect you… it’s almost like packing for a new born baby, you have to make sure you have everything you need with you because you don’t want to be caught some place you don’t have what you need | |

|

| |||

| Adaptation | |||

|

| |||

| Doing things differently | 85 | N3 S2: | I have bottle openers in my house … it opens bottles of different sizes … you learn and you just, you just keep adapting |

| Making trade offs | 86 | B1 S1: | I do save my washing up until I feel that I really do need to go and warm my hands up a bit |

| 87 | N3 S2: | I remember thinking ‘no buttons, no buckles, no shoestrings’ …. Anything like that just had to go. | |

| 88 | B1 S6: | And I’ve had to change how I exercise because I can’t climb anymore. So I swim instead. | |

| 89 | P1 S2: | …if it’s cold I will go for a walk in the snow, I just probably won’t roll around sleigh riding with my grandchildren. But I just can’t let this control my life. I’ve got to keep going and doing what I enjoy, | |

| Seeking help | 90 | N3 S2: | I need to do something like put air in my tyres…I can’t really do something like that if it’s really cold and I have all these gloves on….If I can get somebody to help me with something like that, well then, I would. |

| Not letting it beat you / acceptance | 91 | B1 S3: | But I’ve just learned to get on and do things. It’s painful but I won’t give in to it |

| 92 | B2 S5: | If I have an attack and I’m with somebody and they say, “Oh what’s wrong?” I’ll say, “Oh I’ve got my purple paws again.” And put them in my pocket and I say, “Don’t worry, you carry on and I’ll be alright in about quarter of an hour.” | |

| 93 | P1 S1: | Any time somebody sees it for the first time they get really freaked out, and it gets kind of old hearing, “Oh, you should get that looked at”, or “That’s not normal”. And you’re like, “I know, I’ve known that for a long time. I’ve had it looked at. It’s not necessarily under control but I’m familiar with it.” So that can get old after years and years of that, every time you meet somebody new. It’s not that big of a deal. | |

| 94 | N2 S7: | Even when my hands were real, real black, I never was embarrassed about, you know. I’m not that type of person that gets embarrassed about it. That’s just a part of life. Everybody got something, you know. | |

Q refers to the numbered quote cited in the text. P1 denotes Pittsburgh, group 1; N1, N2, N3 denotes New Orleans groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively; B1, B2 denotes Bath groups 1 and 2; S# denotes subject (participant) number within each focus group.

Theme 6: Uncertainty

All of the preceding themes result in having to manage a life that is filled with uncertainty. This broad-ranging theme encompassed a number of aspects relevant to SSc-RP ranging from the aforementioned uncertainty over the labels we use to describe “attacks” of SSc-RP , uncertainty regarding future disease progression (particularly concerning the development of digital ulcers in patients with prior experience of this complication, Q76–78), the relevance of SSc-RP symptoms on the aging process (Q79) and/or uncertainty regarding the likely efficacy of current/future drug treatments for controlling their SSc-RP (Q80). A change in routine can provoke uncertainty and anxiety regarding the likely impact on the participants’ ability to manage their SSc-RP symptoms (Q81–82). Indeed, a generalised anxiety surrounding finding themselves in an environment in which their symptoms were poorly controlled and the need to make adequate preparation for activities that might impact on SSc-RP symptoms was a recurring theme across the focus groups (Q83–84).

Theme 7: Adaptation

In spite of all the aforementioned unpleasant experiences and challenges, participants reported many examples that demonstrated a remarkable capacity to adapt to life with SSc-RP. Examples included adaptations made in the home environment (Q85), trade-offs accepted in daily activities and social participation (Q86–89) and scenarios in which they might seek help from others (Q90). Acceptance of the need to continue life despite SSc-RP, supported by a strong sense of “not letting it beat you”, emerged within each FG, and a number of quotations highlight the resilience and fortitude with which many patients face their illness (Q91–94).

Discussion

We report the outcome of the first study to specifically examine the patient experience of SSc-RP. The multi-centre design and comprehensive purposive sampling framework has ensured we have captured experiences from a representative cohort of SSc patients in terms of age, gender, disease duration and clinical phenotype; whilst also ensuring diverse geographic, cultural and ethnic participation. Thematic analysis of the anonymised FG transcripts was led by qualitative researchers without direct experience of managing SSc, ensuring an unbiased appraisal of the experiences expressed. The involvement of patient research partners in decision-making has ensured each stage of the study (from devising the FG topic guide to the interpretation of thematic analysis) was appropriate and suitable for achieving the project’s stated aims. We chose FGs over individual patient interviews to allow participants to respond to the opinions of others; challenging and/or validating the views of other group members. FGs can result in a propensity for participants to conform to majority opinion but deliberate efforts were made to create an environment that avoided this. We feel the FGs facilitated the capture of relevant and generalizable experiences across the diverse spectrum of SSc, which might not have emerged from 1:1 patient interviews.

Inductive thematic analysis has identified 7 major inter-related themes (and encompassing subthemes) that constitute the patient experience of SSc-RP that can be arranged within a conceptual map of SSc-RP. Unsurprisingly, the physical symptoms of SSc-RP are positioned at the heart of our conceptual map and featured prominently when participants were asked to describe their RP experiences. Specific physical symptoms of SSc-RP differed between patients with some experiencing a predominance of pain, whereas for others numbness was a more relevant description of their experiences of SSc-RP. The physical symptoms of SSc-RP lead to considerable emotional distress, and impaired ability to use the hands results in significant impact on daily life. Cold exposure is the major trigger for SSc-RP symptoms, although many participants also reported emotional stress as an exacerbating factor. People with SSc take considerable measures to avoid or ameliorate SSc-RP symptoms but self-management approaches are seldom completely effective and can directly impact on functional capacity, social participation and quality of life. Patients adapt over time, developing strategies that increase resilience and help them to carry on life despite SSc-RP, although for many, SSc-RP symptoms contribute to a pervading uncertainty for the future progression of their disease and general well-being.

Our findings have implications for current approaches to assessing SSc-RP. The episodic nature of SSc-RP has resulted in a reliance on patient self-report. Early therapeutic studies of SSc-RP sought a categorical assessment of SSc-RP severity (typically; “better”, “same” or “worse”) (13–16). These were gradually superseded by linear psychometric scales allowing quantification of specific components of SSc-RP symptoms such as pain intensity and the severity of attacks (17–20). The most widely adopted scale is the Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire RP Visual Analogue Subscale (SHAQ RP VAS) which asks patients to consider the extent to which their SSc-RP “problems interfered with your activities” during the preceding week (21). Diary cards have attempted to quantify the frequency and duration of RP attacks, often incorporating linear psychometric global assessments of RP “severity” (22–25). The Raynaud’s Condition Score (RCS) diary was originally developed for two separate studies of oral iloprost (26, 27). The RCS diary collects daily information over a 2-week period of the frequency and duration of RP attacks whilst also incorporating a single item, 11-point numeric rating scale (the RCS) that assesses the “difficulty” patients have experienced from their SSc-RP each day (26, 27). When considering the RCS score, patients are asked to consider the “difficulty” they have experienced due to a range of domains including the number of attacks, the duration of the attacks, symptoms such as pain/numbness and the ability to use their hands (26, 27). Item wording of the RCS differed between the original studies; with the impact of “painful sores” included in the response options for the RCS that underwent post hoc analysis of the validity, feasibility and reliability of the tool using original clinical trial data (27, 28). The RCS diary has subsequently been recommended (alongside the SHAQ RP VAS) for use in clinical trials of SSc-RP (29, 30).

The present work has revealed limitations to current methods for assessing SSc-RP. Firstly, our findings challenge the accepted paradigm of Raynaud’s “attacks” with not all patients identifying with this concept. For many, SSc-RP represents a more nebulous concept that encompasses experiences across several of the themes defined in this work. Moreover, diary monitoring of SSc-RP attack frequency and duration makes no allowance for the considerable measures patients take on a daily basis to prevent or ameliorate symptoms of SSc-RP (themes 4 and 6). In this regard, diary monitoring more accurately provides a combined assessment of peripheral microvascular compromise in conjunction with the effectiveness of self-management approaches adopted by patients to control their symptoms. The RCS, meanwhile, attempts to capture the complex multi-domain construct of SSc-RP in a single item global assessment. This approach risks missing clinically important improvements in individual domains (e.g. pain) as respondents are forced to consider the impact of other domains that might be more resistant to intervention. The item wording (“how much difficulty”) might be influenced by habituation and adaption (themes 4 and 6), whereas the inclusion of “painful sores” in the originally validated RCS might result in inadvertent assessment of digital ulcer disease. These limitations might offer some explanation for the poor agreement between RCS diary returns and objective assessments of peripheral microvascular function in SSc (31). Similarly, the SHAQ RP VAS item wording (“interfered with your activities”) might also be influenced by self-management and adaption (themes 4 and 6). Existing PRO instruments do not capture frequently expressed physical symptoms of SSc-RP such as “tingling” and “hypersensitivity” of the fingertips or “feeling cold”, whereas other important physical symptoms such as pain and numbness might be better assessed in isolation. Emotional distress (theme 2) and the impact of SSc-RP on social participation, family life and work (theme 5) are not captured using existing tools, despite such themes emerging prominently in this study. Additional concerns have been raised regarding existing methods for assessing SSc-RP (e.g. placebo effect and respondent burden) and there is consensus that novel approaches to assessing SSc-RP are required (32).

There was little patient participation in the development of existing PRO instruments for SSc-RP (33). Regulatory bodies now seek target patient population involvement in PRO instrument design when examining labelling claims in medical product development (7) and patient involvement ensures the capture of experiences relevant to the patient in a comprehensible and unambiguous manner (34). Work to develop a novel patient-derived PRO instrument for assessing the severity and impact of SSc-RP, comprising domains/items grounded in the patient experiences of SSc-RP identified in this work is currently underway.

Supplementary Material

Significance and Innovations.

Raynaud’s phenomenon comprises a complex interplay of patient experiences that result in significant morbidity for patients living with systemic sclerosis

Our findings challenge the accepted paradigm of Raynaud’s ‘attacks’ with not all systemic sclerosis patients identifying with this concept

Existing patient reported outcome instruments do not fully capture the patient experience of Raynaud’s phenomenon in systemic sclerosis

Acknowledgments

This work is a Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Vascular Working Group initiative. The authors are grateful to the Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium for funding this project.

Sources of support: Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium. Dr Khanna is support by NIH/NIAMS K24 AR 063120.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors report any conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this work

References

- 1.Botzoris V, Drosos AA. Management of Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78(4):341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voulgari PV, Alamanos Y, Papazisi D, Christou K, Papanikolaou C, Drosos AA. Prevalence of Raynaud’s phenomenon in a healthy Greek population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(3):206–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.3.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker UA, Tyndall A, Czirjak L, Denton C, Farge-Bancel D, Kowal-Bielecka O, et al. Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials And Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(6):754–63. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassel M, Hudson M, Taillefer SS, Schieir O, Baron M, Thombs BD. Frequency and impact of symptoms experienced by patients with systemic sclerosis: results from a Canadian National Survey. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(4):762–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willems LM, Kwakkenbos L, Leite CC, Thombs BD, van den Hoogen FH, Maia AC, et al. Frequency and impact of disease symptoms experienced by patients with systemic sclerosis from five European countries. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(6 Suppl 86) S-88-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirwan JR, Bartlett SJ, Beaton DE, Boers M, Bosworth A, Brooks PM, et al. Updating the OMERACT filter: implications for patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(5):1011–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Administration USDoHaHSFaD. [[06/01/2016]];Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Krueger R, Casey M. Focus Groups: A practical guide for applied research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(11):1747–55. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guest GBA, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamaoka K, Miyasaka N, Sato K, Nishioka K, Okuda M. Therapeutic effects of CS-570, a chemically stable prostacyclin derivative, on Raynaud’s phenomenon and skin ulcers in patients with collagen vascular diseases. Int J Innumotherapy. 1987;3(4):271–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin MF, Dowd PM, Ring EF, Cooke ED, Dieppe PA, Kirby JD. Prostaglandin E1 infusions for vascular insufficiency in progressive systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981;40(4):350–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.40.4.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowd PM, Martin MF, Cooke ED, Bowcock SA, Jones R, Dieppe PA, et al. Treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon by intravenous infusion of prostacyclin (PGI2) Br J Dermatol. 1982;106(1):81–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clifford PC, Martin MF, Sheddon EJ, Kirby JD, Baird RN, Dieppe PA. Treatment of vasospastic disease with prostaglandin E1. Br Med J. 1980;281(6247):1031–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6247.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHugh NJ, Csuka M, Watson H, Belcher G, Amadi A, Ring EF, et al. Infusion of iloprost, a prostacyclin analogue, for treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47(1):43–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.47.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kyle V, Parr G, Salisbury R, Thomas PP, Hazleman B. Prostaglandin E1 vasospastic disease and thermography. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44(2):73–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.44.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyle MV, Belcher G, Hazleman BL. Placebo controlled study showing therapeutic benefit of iloprost in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(9):1403–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klimiuk PS, Kay EA, Mitchell WS, Taylor L, Gush R, Gould S, et al. Ketanserin: an effective treatment regimen for digital ischaemia in systemic sclerosis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(2):107–11. doi: 10.3109/03009748909099925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr The value of the Health Assessment Questionnaire and special patient-generated scales to demonstrate change in systemic sclerosis patients over time. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(11):1984–91. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selenko-Gebauer N, Duschek N, Minimair G, Stingl G, Karlhofer F. Successful treatment of patients with severe secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon with the endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;(45 Suppl 3):ii45–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrick AL, Hollis S, Schofield D, Rieley F, Blann A, Griffin K, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of antioxidant therapy in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(3):349–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, Howell K, Blann A, Bowers E, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma: clinical and biochemical findings in a fifteen-week, randomized, parallel-group, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(12):2646–55. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199912)42:12<2646::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleiro B, Marshall SE, Denton CP, Howell K, Blann A, Welsh KI, et al. Treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40(9):1038–43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.9.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black CM, Halkier-Sorensen L, Belch JJ, Ullman S, Madhok R, Smit AJ, et al. Oral iloprost in Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis: a multicentre, placebo-controlled, dose-comparison study. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(9):952–60. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.9.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wigley FM, Korn JH, Csuka ME, Medsger TA, Jr, Rothfield NF, Ellman M, et al. Oral iloprost treatment in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(4):670–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199804)41:4<670::AID-ART14>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merkel PA, Herlyn K, Martin RW, Anderson JJ, Mayes MD, Bell P, et al. Measuring disease activity and functional status in patients with scleroderma and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2410–20. doi: 10.1002/art.10486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merkel PA, Clements PJ, Reveille JD, Suarez-Almazor ME, Valentini G, Furst DE. Current status of outcome measure development for clinical trials in systemic sclerosis. Report from OMERACT 6. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(7):1630–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khanna D, Lovell DJ, Giannini E, Clements PJ, Merkel PA, Seibold JR, et al. Development of a provisional core set of response measures for clinical trials of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(5):703–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.078923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pauling JD, Shipley JA, Hart DJ, McGrogan A, McHugh NJ. Use of Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging to Assess Digital Microvascular Function in Primary Raynaud Phenomenon and Systemic Sclerosis: A Comparison Using the Raynaud Condition Score Diary. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(7):1163–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pauling JDFT, Hughes M, Gordon JK, Domsic RT, Ingegnoli F, McHugh NM, Johnson SR, Hudson M, Boin F, Ong V, Matucci Cerinic M, Altorok N, Scolnik M, Nikpour M, Shah A, Pope JE, Khanna D, Herrick AL. Attitudes Toward Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments for the Assessment of Raynaud’s Phenomenon in Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pauling JD, Frech TM, Domsic RT, Hudson M. Patient participation in patient-reported outcome instrument development in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirwan JR, Tugwell PS. Overview of the patient perspective at OMERACT 10--conceptualizing methods for developing patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1699–701. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.