Abstract

A hallmark of eukaryotic mRNAs has long been the 5′ end m7G cap. This paradigm was recently amended by recent reports showing Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian cells also contain mRNAs carrying a novel nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) cap at their 5′-end. The presence of an NAD+ cap on mRNA uncovers a previously unknown mechanism for controlling gene expression through nucleoside metabolite-directed mRNA turnover. In contrast to the m7G cap that stabilizes mRNA, the NAD+ cap targets RNA for rapid decay in mammalian cells through the DXO non-canonical decapping enzyme, which removes intact NAD+ from RNA, in a process termed “deNADding”. This review highlights the identification of NAD+ caps, their mode of addition, and functional significance in cells.

Overview

The triphosphorylated 5′ end of a nascent RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) transcript has long been known to undergo covalent modification to incorporate a 5′-5′ linked N7-methyl guanosine (m7G) cap [1, 2]. This modification imparts a layer of protection to the 5′ end of the mRNA from exonucleolytic attack [3, 4]. The m7G cap can further be modified in some RNAs. A class of small nuclear RNAs can be hypermethylated in the cytoplasm on the m7G to generate the trimethylated m2,2,7G cap, which is essential for the reimport of these RNAs into the nucleus [5, 6]. Additional methylation can also occur on the m7G capped mRNA on the ribose 2′ hydroxyl position of the first and second transcribed nucleotides to generate the 2′-O-methylated Cap1 and Cap2 mRNA forms, respectively [7, 8]. These modifications facilitate mRNA translation and contribute to distinguishing host from foreign viral mRNAs [9, 10]. Moreover, a modification identified over forty years ago [8] consisting of methylations at the N6 and 2′-O positions (m6Am) when the first nucleotide following the m7G cap is an adenosine, confers a key layer of epitranscriptomic regulatory information to the 5′ ends of m6Am eukaryotic RNAs [11].

Recent findings in diverse organisms demonstrate epitranscriptomic regulation at the 5′-end cap extends beyond m6Am. A key breakthrough was the observation that bacterial RNA can carry the nucleoside-containing metabolite, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), on their 5′ end [12–14]. These studies established the foundation for recent reports demonstrating NAD+ can also decorate the 5′ end of eukaryotic RNAs in place of an m7G cap in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [15] and in human [16] cells. The NAD+ cap can be introduced by RNA polymerase during transcription initiation with both bacterial RNAP and eukaryotic RNAP II in vitro [17–19], as well as in vivo in bacteria [17]. Thus NAD+ cap addition (NADding) is likely to at least in part, occur with the use of NAD+ as an initiation nucleotide in eukaryotic cells [15, 16]. An important distinction between the canonical m7G cap and NAD+ cap is apparent with mRNA stability and translation. Whereas the m7G cap promotes stability and translation, an NAD+ cap in human cells targets the RNA for rapid decay and does not support translation. The decay is facilitated by the non-canonical decapping enzyme, DXO, which initiates degradation of the RNA by removing the NAD+ cap (deNADding) [16]. Recent advances in our understanding of NADding and deNADding are highlighted in this review with an emphasis on eukaryotic systems.

Regulation of 5′ end cap in bacteria

The initial demonstration that bacterial cells contain RNAs with a 5′-end cap was provided in 2009 [13, 14]. In particular, mass spectrometry of hydrolyzed Escherichia coli and Streptomyces venezuelae bacterial RNAs identified RNA species carrying 5′ end NAD+ [13] or 5′ end dephospho-coenzyme A (dpCoA) [14]. Nevertheless, since these 5′ end nucleoside metabolites were generated by hydrolyses of total RNA, the nature of the RNAs were not clear. The presence of NAD+ “cap” at the 5′ end of bacterial RNA was further validated with the use of a chemo-enzymatic modification of a terminal nicotinamide to an alkyne moiety amendable to “click chemistry”-mediated biotinylation. Biotinylated RNAs are isolated by a streptavidin matrix and identified by high-throughput RNA sequencing in a process termed NAD-captureSeq [20] (Figure 1). NAD-captureSeq established the presence of NAD+ caps at the 5′ end of bacterial RNAs and enabled identification of a subset of small regulatory RNAs that carry an NAD+-cap in Escherichia coli [12] (reviewed in [21]). Development of this approach proved an important tool to identify NAD+ caps in other species.

Figure 1. Schematic of NAD-captureSeq approach.

An exchange of the nicotinamide moiety with an alkyne group is carried out with adenosine diphosphate-ribosylcyclase (ADPRC) and pentynol to attain the “clickable” alkyne group which is biotinylated by a copper catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction (click chemistry) and retained onto streptavidin beads. Identification of the captured RNAs are derived by high throughput RNA sequencing. See [20] for a detailed protocol. Nicotinamide is denoted as Nic, the “p” represents organic monophosphate, the green bar indicates the RNA, the red lines are the alkyne group, the “B” denotes biotin and streptavidin is indicated.

NAD+ capping

Two models can be envisioned for NAD+ incorporation at the 5′ end of RNA, one being a transcriptional process and the second being a post-transcriptional process. Addition of the NAD+ cap in bacteria proceeds through the former mechanism where NAD+ serves as a non-canonical initiating nucleotide (NCIN) in place of ATP as the first nucleotide [17]. The NCIN model for NAD+ capping is supported by evidence that bacterial RNAP can use NAD+ as an initiating nucleotide in place of ATP in vitro [17–19]. Furthermore, promoter sequence determinants upstream of the transcription start site can influence the efficiency by which NAD+ can serve as an NCIN in vitro [17]. A direct correlation is observed between the promoter sequence determinants for use of NAD+ as an NCIN in vitro and the amount of NAD+-capped RNA detected in E. coli [17]. Correlations between the effects of promoter sequence on the efficiency of use of NAD+ as an NCIN in vitro and the amounts of NAD+-capped RNA generated in vivo provide strong support for the proposal that most (if not all) NAD+-capped RNA in bacterial cells is generated by use of NAD+ as an NCIN [17].

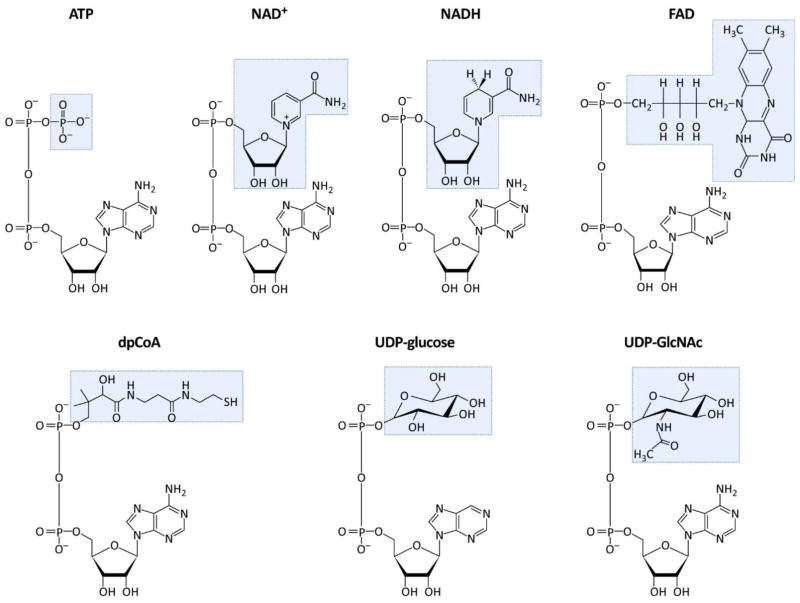

Interestingly, the capacity of bacterial RNAP to incorporate NCINs is not restricted to NAD+. Transcription initiation through the adenosine residue of nucleoside metabolites (FIGURE 2) is also observed in vitro including the reduced form of NAD+ (NADH), flavin adenine diphosphate (FAD) and desphospho coenzyme A (dpCoA), as well as uridine containing metabolites including uridine diphosphate glucose (UDP-glucose), and uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) [17–19]. To date, dpCoA is the only nucleoside metabolite other than NAD+, detected at the 5′ end of bacterial RNA [14].

Figure 2. Adenosine-containing nucleoside metabolites.

Structure of each metabolite is shown. All structures have a common adenosine diphosphate. The unique features of each metabolite are shaded in blue.

NudC and deNADding of bacterial RNA

In mammals, the protective 5′ end m7G cap is removed by a subclass of nucleoside diphosphate linked to another moiety X (Nudix) hydrolase family of proteins including Dcp2, Nudt3 and Nudt16 known to function as decapping enzymes in cells, and Nudt2, Nudt12, Nudt15, Nudt17 and Nudt19 with in vitro decapping activity [22]. These decapping enzymes can remove the cap structure to generate a 5′ end monophosphorylated RNA substrate (Figure 3A) that is subjected to subsequent exonucleolytic decay. Similarly, in bacteria, the RppH Nudix protein can remove the first two phosphates from the 5′ end of triphosphorylated RNA to generate a monophosphorylated 5′ end RNA [23] that can serve as a substrate for RNaseE-directed decay [24]. Another bacterial Nudix protein, NudC, previously shown to hydrolase free NAD(H) into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN(H)) plus AMP [25] possesses deNADding activity that hydrolyzes NAD+-capped RNA to NMN plus 5′ monophosphate RNA [12] (Figure 3B). The significance of NudC deNADding activity was demonstrated in E. coli harboring a deleted NudC gene, where the steady state accumulation of NAD+-capped small RNAs increased [12] as did their stability [17]. These findings indicate the NAD+ cap functions in a role analogous to the eukaryotic m7G cap to stabilize RNA in bacteria and NudC is a deNADding enzyme that removes the protective NAD+ cap to promote decay. Furthermore, in vitro data shows that NudC can remove dpCoA from the 5′ end of RNA [17], suggesting a potential role for NudC in the removal of dpCoA caps in vivo. It is likely now a question of when, rather than if, additional nucleoside metabolite 5′ end caps are identified, which in turn will raise new questions of whether the new caps are also removed by NudC or removed by other as yet uncharacterized enzymes.

Figure 3. decapping and deNADding activities.

(A) Canonical and incomplete cap decapping. Canonical m7G-cap decapping activity by Dcp2, Nudt3 and Nudt16 decapping enzymes releasing m7Gpp and 5′ monophosphate RNA (Left). Non-canonical incomplete cap decapping activity by DXO removes either the diphosphate from a triphosphorylated RNA or the entire cap structure of an unmethylated capped RNA (Right). (B) deNADding activities of NudC and DXO are shown. NudC cleaves the NAD+ cap between the two phosphates to release nicotinamide mononucleotide (Nicp) and 5′ monophosphate RNA (Left). DXO hydrolyzes the phosphodiester linkage 3′ to the adenosine to remove the entire NAD+ moiety and generate a 5′ monophosphate RNA (Right). Labeling is as in the legend to Figure 1 and the red arrow indicates the enzyme cleavage site.

Regulation of non-canonical 5′ end cap in mammalian cells

Addition and removal of the m7G cap has been extensively studied in the last four decades with little emphasis on alternative caps. In eukaryotes, the first 5′ mRNA cap to be identified, the m7G cap [1, 2], functions to stabilize RNA and facilitate mRNA translation as well as contribute to RNA splicing and RNA transport [26]. Additional caps have subsequently been described including the N6- and 2′-O-methylated m6Am. The m6Am cap confers a key layer of regulatory information to 5′ ends of mRNA because this cap is less susceptible to decapping by the Dcp2 decapping enzyme [11]. Furthermore, capping does not always proceed to completion in eukaryotic cells. Incomplete caps lacking the N7 methyl moiety or lacking a cap altogether, can also be generated. These incomplete caps are detected and cleared by a 5′-end quality control (5′QC) mechanism employing the DXO family of proteins [27–29] (Figure 3A). Existence of diverse mRNA caps underscores the significance of regulatory mechanisms that incorporate or remove the 5′-end cap and their influence on controlling gene expression.

NAD+ capping

Recently, the NAD-captureSeq approach was used to demonstrate NAD+ caps extend beyond bacterial RNA and are also present in human cells [16]. The majority of NAD+-capped mRNAs overlap with canonical m7G-capped mRNAs indicating mRNAs can be present as two distinct populations in cells that differ in the state of their 5′-end cap. One population carries the canonical m7G-cap, while the other, estimated to comprise ~1–6% of a respective mRNA [16], harbors an NAD+ cap. Interestingly, distinctions between the reads obtained from NAD-captureSeq and standard RNA-seq are also evident. For example, while the proportion of small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) are higher in NAD+-capped RNA populations, the proportion of another class of NAD+-capped RNAs consisting of antisense transcripts, are significantly lower than that in m7G-capped RNA [16] suggestive of transcript preference in NAD+ capping (see below).

Post-transcriptional NAD+ capping in mammalian cells

The demonstration that eukaryotic RNAP II can use NAD+ as an initiating nucleotide in vitro [17] suggests that NAD+-capped mRNAs detected in yeast [15] and human cells [16] are also generated by use of NAD+ as an NCIN by RNAP II. However, a similar transcriptional NCIN model cannot account for all mammalian NAD+-capped RNAs. In particular, the existence of an NAD+ cap on mammalian snoRNAs and the related small Cajal body RNAs (scaRNAs) indicates a post-transcriptional mechanism is also involved [16]. SnoRNAs and scaRNAs function as guide RNAs in the pseudouridylation and methylation of ribosomal RNAs and U-rich small nuclear RNAs, respectively [30, 31]. They are predominantly encoded within host gene introns and generated as exonucleolytic-resistant ribonucleoprotein complexes lacking a modification at their 5′ end [30–32]. The presence of NAD+ caps on intronic RNAs strongly suggest NAD+ caps can be added to the 5′ end of RNAs post-transcriptionally and supports the existence of an NAD+ capping mechanism in addition to the NCIN model in mammalian cells.

Addition of the canonical m7G cap to the 5′ end of pre-mRNAs occurs cotranscriptionally by the combination of three enzymatic activities: a triphosphatase activity, a guanylyltransferase activity, and a methyltransferase activity [33, 34]. Three different proteins carry out the distinct activities in yeast, while the triphosphatase and guanylyltransferase activities are carried out by a single bifunctional capping enzyme in mammals [35]. A multistep cytoplasmic recapping of 5′ end monophosphorylated RNA has also been reported [36]. Although the mechanism for NAD+ cap addition is unknown, at least two distinct modes of NADding can be envisioned. First, nicotinamide or its derivative, could be linked onto an RNA containing a 5′ adenosine. Second, addition of an intact NAD+ molecule onto the 5′ end of an RNA regardless of the first nucleotide on the RNA. Based on current identified RNA ligases [37] a simple ligation of NAD+ onto sno/scaRNA appears unlikely as the mechanism for NADding. Whether NADding occurs through a currently unknown RNA ligase or through a multiprotein sequential process is unknown. Identification of the NADding mechanism and the enzyme(s) involved will be an important step forward in our understanding of NAD+-capping and provide insight into potential modes of NADding regulation.

DXO and deNADding of mammalian RNA

The DXO family of proteins are non-canonical decapping enzymes, that remove the entire cap structure of capped, or incompletely capped, RNA [28] (Figure 3A). This activity is distinct from that of the “traditional” decapping enzymes, Dcp2 [38–40], Nudt3 [41] and Nudt16 [42] that cleave the cap within the triphosphate linkage (Figure 3A). The ability of DXO to function on incomplete cap structures suggested a potential role for this enzyme in the removal of NAD+-caps. Consistent with this notion, DXO, but not Dcp2, exhibits deNADding activity on RNA transcripts in vitro [16]. The deNADding activity of DXO results in removal of the entire NAD+ moiety leaving a 5′ end monophosphate RNA which is mechanistically distinct from that of NudC-mediated deNADding, which results in the conversion of NAD+-capped RNA to NMN plus 5′ monophosphate RNA (Figure 3B). Notably, the activity of DXO on NAD+-capped RNA is ~6 fold more efficient than the activity on m7G-capped RNA, suggesting deNADding is likely a prominent activity for DXO in cells.

Two lines of evidence support a role for DXO in modulating levels of NAD+-capped RNAs in cells. The first is from transfected generic RNAs. NAD+-capped RNAs transfected into HEK293T cells lacking DXO are more stable than NAD+-capped RNAs transfected into cells lacking the Dcp2 decapping enzyme, which does not cleave NAD+ capped RNA [16]. Second, NAD+-capped RNA levels are elevated in cells lacking DXO, with the most prominent being the sno/scaRNAs, which can increase up to nine fold. Together, these findings indicate DXO is a deNADding enzyme in cells that specifically targets a subset of NAD+-capped RNAs.

The established role for the DXO family of proteins in 5′QC [43] raises an interesting question. Is NAD+ capping a result of random aberrant incorportation of NAD+ as an initiating nucleotide that is subjected to the DXO 5′QC mechanism? Although this remains a formal posibility, several observations argue against nonspecific NAD+-capping as the promonent pathway. First, random incorporation of NAD+ caps would be expected at all adenosine transcription initiation sites, resulting in proportional random distribution of NAD+ caps at the 5′ end of RNAs. However, this is not the case as subsets of RNA classes contain either higher or lower proportions of NAD+ caps relative to the same class of RNAs containing canonical caps [16]. The nonuniform distribution of NAD+-capped RNAs supports the premise that NAD+ capping is not a stochastic event uniformly NAD+ capping all RNAs. A comparison of cellular NAD+ levels under parameters that increase or decrease NAD+ levels, to that of potential corresponding changes in NAD+-capped RNA levels in cells can begin to address this point. An outcome of 1:1 uniformity between cellular NAD+ and NAD+-caps would be predicted from random incorporation, while variances between the two would be observed with specific NAD+-capping. Second, and perhaps most significantly, identification of NAD+-caps on a subset of sno/scaRNAs demonstrates NAD+-capping is an orchestrated and not a random process, at least for this subset of RNAs.

NAD+ cap promotes RNA decay in human cells

In contrast to the m7G cap, which stabilizes the 5′ end of mRNAs, the 5′ NAD+-cap promotes decay of RNAs it is attached to. NAD+-capped and polyadenylated luciferase mRNAs transfected into HEK293T cells are less stable than the same mRNAs lacking a 5′-end cap [16]. Therefore, the NAD+-cap does not serve as a simple passive marker on the 5′ end of RNAs, but rather functions to actively recruit and confer deNADding and decay. Moreover, the decay of an NAD+-capped mRNA is mediated through DXO as indicated by the equivalent stability of an NAD+-capped luciferase mRNA to that of an m7G-capped luciferase mRNA in DXO-knockout cells. It appears the NAD+ cap fulfills a function similar to mRNA 3′ terminal uridylation. The uridine tract on the 3′ end of an mRNA promotes its decay [44] by is susceptibility to the Dis3L2 3′ exonuclease [45, 46] as well as by recruiting the mRNA decapping complex [47, 48]. By analogy, the NAD+-cap serves as a 5′-end tag to recruit DXO and facilitate the demise of the mRNA (Figure 4). The deNADding activity of DXO hydrolyzes and releases NAD+, leaving the 5′ monophosphorylated mRNA molecule which can further be degraded by the intrinsic 5′-3′ exonucleolytic activity of DXO [28].

Figure 4. Model of DXO-mediated NAD+-capped mRNA decay.

(Left) DXO can detect and remove the NAD+ cap and degrade the mRNA by its intrinsic 5′ to 3′ exonucleolytic activity. The polyadenylated tail is shown as AAAn with the “An ?” representing the unknown parameter of whether the tail is deadenylated to an oligoadenylated tail prior to deNADding. The DXO enzyme is as shown. Labeling is as in the legend to Figure 1. (Right) Decay of m7G capped RNA by decapping (blue) and 5′ exonuclease (brown) is shown. The Stop sign denotes a stable 5′ end decay intermediate refractory to exonucleolytic decay. The potential NADding of the stable intermediate to further promote decay is represented by the blue arrow and question mark.

An important question remains regarding the physiological function of the NAD+ cap, to which the NAD+ capped sno/scaRNAs may provide a clue. Intronic sno/scaRNAs are generated by their exonucleolytic resistant property following release of the spliced intron [49] and are therefore expected to be refractory to exonucleolytic decay as exemplified by snoRNA associated long noncoding RNAs (sno-lncRNAs) which consist of stable intronic RNAs flanked on both termini by snoRNAs [50]. Addition of an NAD+ cap could provide a mechanism to recruit the DXO exonuclease to promote their decay. It is also plausible that 5′ end stable decay intermediates of mRNAs that originally initiated as a m7G capped mRNA, could potentially be NAD+ capped to further promote their decay (Figure 4). However, it should be noted that this latter scenario is a model that still requires experimental verification.

NAD+ cap does not support translation in human cells

A prominent feature of the m7G cap is its role in translation initiation by recruitment of the initiation complex onto the mRNA [51]. Translation initiation complex assembly onto an mRNA can also occur by m7G cap-independent mechanisms [52]. The capacity of the NAD+ cap in translation was assessed by transfection of NAD+-capped and polyadenylated luciferase mRNA into HEK293T cells where the level of translation from this mRNA was no more than the background level of translation from an identical uncapped RNA [16]. These findings show that the NAD+ cap does not support translation of the exogenous mRNA used. However, these studies cannot rule out the possibility that the NAD+ cap may promote alternative cap independent mechanisms within the proper endogenous mRNA context. NAD-captureSeq of polysomal mRNA fractions will be necessary to begin addressing cap-alternative modes of potential NAD+-capped mRNA translation.

Regulation of 5′ end non-canonical cap in yeast

NAD+-capped mRNAs were also recently identified in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae using the NAD-captureSeq approach [15] reinforcing the widespread utilization of NAD+ caps in diverse organisms.

NAD+ capping

Addition of the NAD+ cap in yeast appears to predominantly occur through the NCIN model of NADding [15], indicating transcriptional incorporation of an NAD+ cap is a prevalent theme across multiple kingdoms. Interestingly, the extent of NAD+ capped mRNA is comparable between yeast and human cells. Estimates of NAD+-capped mRNA in yeast range from 1–5% of a given mRNA population [15] which is similar to mammalian cells under normal growth conditions [16]. However, NAD+-capped mRNAs increase in yeast cells grown in synthetic media [15] an indication that the levels of NAD+-capped mRNA detected under optimal growth conditions may be an underestimation. The results also imply cellular stress may contribute to the extent of NAD+ capped mRNA. Whether additional cellular or environmental conditions alter levels of NAD+ capped mRNA in yeast remains unknown. Beyond nuclear encoded mRNAs, gene ontology analysis of the NAD+-capped transcripts in yeast uncovered an enrichment of mitochondrial mRNAs [15]. Mitochondrial transcription begins with an adenosine as the first nucleotide [53], suggesting NAD+ capping of mitochondrial mRNA through the NCIN mechanism may provide an avenue of coordinating the fate of RNA with cellular metabolism.

Removal of the NAD+ cap

At present the functional role of the NAD+ cap in yeast has not been determined. Whether NAD+ caps stabilize mRNAs as observed in bacteria [17], destabilize RNA as observed in mammals [16], and/or impact translation, is unknown. Nevertheless, insight into potential deNADding enzymes exist. Yeast contain two members of the DXO family of proteins, Rai1p [54] and Dxo1p [27]. Rai1p forms a heterodimer with the nuclear 5′-3′ exoribonuclease, Rat1p [54, 55], which degrades RNAs carrying a 5′ monophosphate. Rai1p can generate 5′ monophosphorylated RNA substrates for Rat1p by catalyzing the removal of an incomplete cap lacking the N7 methyl moiety [29]. Dxo1p can remove an incomplete cap lacking the N7 methyl moiety and similar to DXO, contains intrinsic 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activity to degrade the decapped mRNA [27]. Similar to mammalian DXO, the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rai1p and Kluyveromyces lactis Dxo1p exhibit deNADding activity in vitro [16]. Furthermore, the deNADding activity of both proteins is more robust than their respective incomplete cap decapping activities. Whether one or both proteins function as deNADding enzymes in yeast cells, and whether they target specific subclasses of NAD+-capped RNAs will be important areas to address.

The yeast enhancer of decapping protein, Edc3, is an NAD(H) binding protein and reported to cleave free NAD+ in vitro at excess protein concentrations [56]. These observations suggest Edc3 may function as a deNADding enzyme. However, NAD(H) binding influences the cellular localization of Edc3 in yeast cells [56] implying that similar to the sirtuin family of DNA deacetylases that require NAD+ binding for their function [57, 58], NAD(H) may be an essential Edc3 cofactor rather than a substrate on the 5′ of an mRNA. Whether Edc3 utilizes NAD(H) as a cofactor or functions as a deNADding enzyme remains to be determined.

Potential link between NAD+ capping and cellular metabolism

RNA-binding proteins have been known to bridge RNA metabolism and cellular metabolism since the 1990’s with the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle enzyme, aconitase, being one of the best studied examples [59]. In the absence of iron, the aconitase enzyme is endowed with RNA-binding properties to bind a stem loop structure and influence mRNA stability and translation [60, 61]. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) glycolytic enzyme is also an RNA-binding protein and its binding activity is modulated by the presence of NAD+. NAD+ inhibits the RNA binding property of GAPDH, but is necessary for GAPDH enzymatic activity [62]. The identification of NAD+ capped RNAs indicates the connection between RNA fate and cellular metabolism may extend beyond just RNA-binding proteins and include the RNA itself through its 5′ end cap. The fact that DXO regenerates an intact NAD+ from an mRNA is suggestive of an intimate link between these processes. Cellular NAD+ levels are altered in response to energy stresses, such as glucose deprivation [63], fasting [64, 65] and caloric restriction [66] indicating the nutrient state of a cell influences NAD+ concentrations. It is highly probable that such changes would impact NAD+ capping. Since nutrient deprivation can manifest altered mRNA stability [67–69] and NAD+ caps promote mRNA decay [16], a tantalizing possibility exists that the energetic state of a cell can impact NAD+-capping and in turn mRNA turnover. Such a connection could position the NAD+ cap as an important rheostat influencing the stability of transcripts involved in cellular energetics. The relative higher level of NAD+-capped RNA observed in stationary phase bacteria [17] and yeast grown in synthetic media [15] support such a possibility.

Concluding Remarks

The discovery of the m7G cap on mRNAs over four decades ago opened a new and exciting area of research for RNA biology and the control of mRNA fate through its addition and removal, that still continues to date. Discovery of a new RNA cap, the NAD+ cap, provides yet another layer of complexity and excitement to the field. We have only begun delineating the role of the NAD+ cap in mRNA turnover with much of the molecular details for the function and outcome of the NAD+ cap unknown. Other than transcriptional initiation, how is the NAD+ cap added and what are the enzyme(s) involved? Does the function of an NAD+ cap extend beyond RNA turnover? Although an NAD+-capped exogenous luciferase mRNA was not translated when transfected into cells [16], could endogenous NAD+-capped mRNA be translated by cap-independent mechanisms [70], bypassing the need for a m7G cap? Is there an equivalent to the eIF4E m7G cap binding protein for the NAD+ cap? If so, would it modulate mRNA turnover, translation or localization?

Identification of the DXO family of proteins as deNADding enzymes is a major step towards understand the physiological regulation of NAD+ capping. However, based on the precedent in mammalian cells where there are multiple m7G decapping enzymes [22], additional deNADding enzymes with selective specificities are expected. Moreover, all the studies thus far have focused on NAD+ capping. RNAP can also incorporate the reduced form of NAD+, NADH as the first nucleotide [17]. Are RNAs capped with NADH and considering the contrasting energetic states of NAD+ and NADH, do RNAs with these modifications have distinct functions? Beyond the NAD+ cap, a pressing question is whether additional nucleoside metabolites are used as a 5′ end cap. Polymerases can incorporate NCIN’s in vitro [71] and E. coli and S. venezuelae RNAs can contain dpCoA at their 5′ end [14]. It is highly likely that the NAD+ cap is only the beginning of a new revolution in 5′ end capping (See Outstanding Questions). We are at an analogous position with nucleoside metabolite capping of mRNA as we were in the 1970’s with the discovery of the m7G cap. The road ahead will undoubtedly be just as exciting and full of surprising new discoveries to be uncovered.

Outstanding Questions.

What determines the proportion of a given mRNAs capacity to be capped with an NAD+, rather than a m7G cap and does the percentage of NAD+ cap on any given mRNA population change with intracellular or extracellular stimuli?

Capping of intronic RNAs must proceed through a post-transcriptionally NAD+ capping mechanism. What are the enzymes and the pathway involved?

Do cells possess an NAD+ cap-binding protein (NCBP) and is the state of the NAD+ cap modulated by such a protein?

Do eukaryotic cells also contain additional 5′-end nucleoside metabolite caps other than NAD+ and do they provide a conduit between RNA metabolism and cellular energetics?

Trends.

Eukaryotic cells contain NAD+ capped RNAs

NAD+ cap can be added by both transcriptional initiation with NAD+ in place of ATP, as well as a novel NAD+ capping mechanism.

5′ end NAD+ cap promotes rapid decay of the RNA at least in part by the DXO family of proteins.

Acknowledgments

Insightful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript by Drs. Xinfu Jiao and Bryce Nickels are greatly appreciated. This work was supported by NIH grant GM067005.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Furuichi Y, et al. Reovirus messenger RNA contains a methylated, blocked 5′-terminal structure: m-7G(5′)ppp(5′)G-MpCp. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72(1):362–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei CM, et al. Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell. 1975;4(4):379–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furuichi Y, et al. 5′-Terminal structure and mRNA stability. Nature. 1977;266(5599):235–9. doi: 10.1038/266235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Kiledjian M. Functional Link between the Mammalian Exosome and mRNA Decapping. Cell. 2001;107(6):751–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamm J, Mattaj IW. Monomethylated cap structures facilitate RNA export from the nucleus. Cell. 1990;63(1):109–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90292-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamond AL. The trimethyl-guanosine cap is a nuclear targeting signal for snRNPs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15(12):451–2. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90292-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams JM, Cory S. Modified nucleosides and bizarre 5′-termini in mouse myeloma mRNA. Nature. 1975;255(5503):28–33. doi: 10.1038/255028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei C, et al. N6, O2′-dimethyladenosine a novel methylated ribonucleoside next to the 5′ terminal of animal cell and virus mRNAs. Nature. 1975;257(5523):251–3. doi: 10.1038/257251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daffis S, et al. 2′-O methylation of the viral mRNA cap evades host restriction by IFIT family members. Nature. 2010;468(7322):452–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devarkar SC, et al. Structural basis for m7G recognition and 2′-O-methyl discrimination in capped RNAs by the innate immune receptor RIG-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(3):596–601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515152113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauer J, et al. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature. 2017;541(7637):371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature21022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahova H, et al. NAD captureSeq indicates NAD as a bacterial cap for a subset of regulatory RNAs. Nature. 2015;519(7543):374–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YG, et al. LC/MS analysis of cellular RNA reveals NAD-linked RNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(12):879–81. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kowtoniuk WE, et al. A chemical screen for biological small molecule-RNA conjugates reveals CoA-linked RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(19):7768–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900528106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walters RW, et al. Identification of NAD+ capped mRNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(3):480–485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619369114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiao X, et al. 5′ End Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Cap in Human Cells Promotes RNA Decay through DXO-Mediated deNADding. Cell. 2017;168(6):1015–1027. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bird JG, et al. The mechanism of RNA 5′ capping with NAD+, NADH and desphospho-CoA. Nature. 2016;535(7612):444–7. doi: 10.1038/nature18622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Julius C, Yuzenkova Y. Bacterial RNA polymerase caps RNA with various cofactors and cell wall precursors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(14):8282–8290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malygin AG, Shemyakin MF. Adenosine, NAD and FAD can initiate template-dependent RNA synthesis catalyzed by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. FEBS Lett. 1979;102(1):51–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80926-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winz ML, et al. Capture and sequencing of NAD-capped RNA sequences with NAD captureSeq. Nat Protoc. 2017;12(1):122–149. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaschke A, et al. Cap-like structures in bacterial RNA and epitranscriptomic modification. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;30:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grudzien-Nogalska E, Kiledjian M. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2016. New Insights into Decapping Enzymes and Selective mRNA Decay. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deana A, et al. The bacterial enzyme RppH triggers messenger RNA degradation by 5′ pyrophosphate removal. Nature. 2008;451(7176):355–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouvier M, Carpousis AJ. A tale of two mRNA degradation pathways mediated by RNase E. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82(6):1305–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frick DN, Bessman MJ. Cloning, purification, and properties of a novel NADH pyrophosphatase. Evidence for a nucleotide pyrophosphatase catalytic domain in MutT-like enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(4):1529–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramanathan A, et al. mRNA capping: biological functions and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(16):7511–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang JH, et al. Dxo1 is a new type of eukaryotic enzyme with both decapping and 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(10):1011–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiao X, et al. A mammalian pre-mRNA 5′ end capping quality control mechanism and an unexpected link of capping to pre-mRNA processing. Mol Cell. 2013;50(1):104–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiao X, et al. Identification of a quality-control mechanism for mRNA 5′-end capping. Nature. 2010;467(7315):608–11. doi: 10.1038/nature09338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dieci G, et al. Eukaryotic snoRNAs: a paradigm for gene expression flexibility. Genomics. 2009;94(2):83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filipowicz W, Pogacic V. Biogenesis of small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14(3):319–27. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawaji H, et al. Hidden layers of human small RNAs. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghosh A, Lima CD. Enzymology of RNA cap synthesis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2010;1(1):152–72. doi: 10.1002/wrna.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuman S. Capping enzyme in eukaryotic mRNA synthesis. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;50:101–29. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yue Z, et al. Mammalian capping enzyme complements mutant Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking mRNA guanylyltransferase and selectively binds the elongating form of RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(24):12898–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoenberg DR, Maquat LE. Re-capping the message. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(9):435–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burroughs AM, Aravind L. RNA damage in biological conflicts and the diversity of responding RNA repair systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(18):8525–8555. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lykke-Andersen J. Identification of a human decapping complex associated with hUpf proteins in nonsense-mediated decay. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(23):8114–21. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8114-8121.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Dijk E, et al. Human Dcp2: a catalytically active mRNA decapping enzyme located in specific cytoplasmic structures. EMBO J. 2002;21(24):6915–24. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z, et al. The hDcp2 protein is a mammalian mRNA decapping enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(20):12663–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192445599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grudzien-Nogalska E, et al. Nudt3 is an mRNA decapping enzyme that modulates cell migration. RNA. 2016 doi: 10.1261/rna.055699.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song MG, et al. Multiple mRNA decapping enzymes in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2010;40(3):423–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jurado AR, et al. Structure and function of pre-mRNA 5′-end capping quality control and 3′-end processing. Biochemistry. 2014;53(12):1882–98. doi: 10.1021/bi401715v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheer H, et al. Uridylation Earmarks mRNAs for Degradation… and More. Trends Genet. 2016;32(10):607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malecki M, et al. The exoribonuclease Dis3L2 defines a novel eukaryotic RNA degradation pathway. EMBO J. 2013;32(13):1842–54. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ustianenko D, et al. TUT-DIS3L2 is a mammalian surveillance pathway for aberrant structured non-coding RNAs. EMBO J. 2016;35(20):2179–2191. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mullen TE, Marzluff WF. Degradation of histone mRNA requires oligouridylation followed by decapping and simultaneous degradation of the mRNA both 5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′. Genes Dev. 2008;22(1):50–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1622708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song M, Kiledjian M. 3′ Terminal oligo U-tract-mediated stimulation of decapping. RNA. 2007;13(12):2356–2365. doi: 10.1261/rna.765807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiss T, Filipowicz W. Exonucleolytic processing of small nucleolar RNAs from pre-mRNA introns. Genes Dev. 1995;9(11):1411–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.11.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin QF, et al. Long noncoding RNAs with snoRNA ends. Mol Cell. 2012;48(2):219–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Topisirovic I, et al. Cap and cap-binding proteins in the control of gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011;2(2):277–98. doi: 10.1002/wrna.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lacerda R, et al. More than just scanning: the importance of cap-independent mRNA translation initiation for cellular stress response and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(9):1659–1680. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2428-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turk EM, et al. The mitochondrial RNA landscape of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xue Y, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAI1 (YGL246c) is homologous to human DOM3Z and encodes a protein that binds the nuclear exoribonuclease Rat1p. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(11):4006–15. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4006-4015.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiang S, et al. Structure and function of the 5′-->3′ exoribonuclease Rat1 and its activating partner Rai1. Nature. 2009;458(7239):784–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walters RW, et al. Edc3 function in yeast and mammals is modulated by interaction with NAD-related compounds. G3 (Bethesda) 2014;4(4):613–22. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.010470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katsyuba E, Auwerx J. Modulating NAD(+) metabolism, from bench to bedside. EMBO J. 2017;36(18):2670–2683. doi: 10.15252/embj.201797135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hentze MW, Preiss T. The REM phase of gene regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(8):423–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hentze MW, Kuhn LC. Molecular control of vertebrate iron metabolism: mRNA-based regulatory circuits operated by iron, nitric oxide, and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(16):8175–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wallander ML, et al. Molecular control of vertebrate iron homeostasis by iron regulatory proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(7):668–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagy E, Rigby WF. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase selectively binds AU-rich RNA in the NAD(+)-binding region (Rossmann fold) J Biol Chem. 1995;270(6):2755–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fulco M, et al. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev Cell. 2008;14(5):661–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Canto C, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458(7241):1056–60. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canto C, et al. Interdependence of AMPK and SIRT1 for metabolic adaptation to fasting and exercise in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2010;11(3):213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen D, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of SIRT1 by calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 2008;22(13):1753–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.1650608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kilberg MS, et al. Nutritional control of gene expression: how mammalian cells respond to amino acid limitation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:59–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kiledjian M, et al. Normal and Aberrantly Capped mRNA Decapping. In: Chanfreau GFaTF., editor. The Enzymes: Eukaryotic RNases and their partners in RNA degradation and biogenesis. Academic Press; 2012. pp. 165–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Talarek N, et al. Quantification of mRNA stability of stress-responsive yeast genes following conditional excision of open reading frames. RNA Biol. 2013;10(8):1299–308. doi: 10.4161/rna.25355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitchell SF, Parker R. Modifications on Translation Initiation. Cell. 2015;163(4):796–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barvik I, et al. Non-canonical transcription initiation: the expanding universe of transcription initiating substrates. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017;41(2):131–138. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]