Abstract

Background

Anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous (IV) N-acetylcysteine (NAC) are well-recognized adverse events during treatment for acetaminophen (APAP) poisoning. Uncertainty exists regarding their incidence, severity, risk factors, and management. We sought to determine the incidence, risk factors, and treatment of anaphylactoid reactions to IV NAC in a large, national cohort of patients admitted to hospital for acetaminophen overdose.

Methods

This retrospective medical record review included all patients initiated on the 21-h IV NAC protocol for acetaminophen poisoning in 34 Canadian hospitals between February 1980 and November 2005. The primary outcome was any anaphylactoid reaction, defined as cutaneous (urticaria, pruritus, angioedema) or systemic (hypotension, respiratory symptoms). We examined the incidence, severity and timing of these reactions, and their association with patient and overdose characteristics using multivariable analysis.

Results

An anaphylactoid reaction was documented in 528 (8.2%) of 6455 treatment courses, of which 398 (75.4%) were cutaneous. Five hundred four (95.4%) reactions occurred during the first 5 h. Of 403 patients administered any medication for these reactions, 371 (92%) received an antihistamine. Being female (adjusted OR 1.24 [95%CI 1.08, 1.42]) and having taken a single, acute overdose (1.24 [95%CI 1.10, 1.39]) were each associated with more severe reactions, whereas higher serum APAP concentrations were associated with fewer reactions (0.79 [95%CI 0.68, 0.92]).

Conclusion

Anaphylactoid reactions to the 21-h IV NAC protocol were uncommon and involved primarily cutaneous symptoms. While the protective effects of higher APAP concentrations are of interest in understanding the pathophysiology, none of the associations identified are strong enough to substantially alter the threshold for NAC initiation.

Keywords: Acetaminophen, Paracetamol, N-acetylcysteine, Adverse drug event

Introduction

Adverse reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine (NAC) including urticaria, pruritus, facial flushing, wheezing, dyspnea, and hypotension are well-recognized complications of treatment for acetaminophen poisoning [1, 2]. These reactions have been termed “anaphylactoid” as the mechanism is believed to involve non-IgE-mediated histamine release or direct complement activation. Importantly, and unlike true anaphylaxis, prior exposure to NAC is not required, nor is continued or future treatment contraindicated [3]. The reported incidence varies widely from 3.7 to 44%, likely due to differences in the definition of an anaphylactoid reaction; the inclusion of non-anaphylactoid adverse events such as nausea, vomiting, and headache; the initial rate of infusion of IV NAC; treatment thresholds including variable Rumack-Matthew nomogram treatment lines; and retrospective versus prospective data collection [2, 4, 5].

It is believed that several factors are associated with an increased risk of anaphylactoid reaction to NAC, including a history of asthma [6, 7], atopic disease [5], family history of allergy [8], lower acetaminophen concentrations on admission [4, 8–10], female sex [10], younger age [10], lower alcohol consumption [10], a history of previous reaction to NAC [10], and a time interval from ingestion to treatment with NAC greater than 8 h [4]. In addition, two randomized clinical trials and several prospective studies have examined the effect of changing the infusion protocol on adverse reactions, with contradictory results [11–13]. A better understanding of NAC anaphylactoid reactions would inform the ongoing discussion regarding optimal loading protocols [12, 13], risk-benefit of the intravenous route over oral [14], and treatment threshold for NAC [15], an essential antidote which must often be dosed empirically before specific signs of toxicity are apparent. Furthermore, variations in the management of anaphylactoid reactions still exist, and clinicians may be reluctant to re-administer NAC following such a reaction, despite expert consensus supporting such a practice [1].

A large, multicenter study of acetaminophen overdose patients admitted to Canadian hospitals over 25 years provided a unique opportunity to study the incidence, clinical features, risk factors, and management of anaphylactoid reactions to IV NAC. We sought to estimate the incidence, timing, type, and severity of anaphylactoid reactions to the 21-h IV NAC protocol and to identify the risk factors associated with these reactions.

Methods

Design

This was a planned analysis of the Canadian Acetaminophen Overdose Study database, a large, retrospective cohort of patients hospitalized following acetaminophen overdose. The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary approved the study.

Participants and Setting

The Canadian Acetaminophen Overdose Study was a structured explicit medical record review of all patients admitted for acetaminophen poisoning to 34 hospitals in eight large Canadian cities between February 1980 and November 2005. Potentially eligible patients with acetaminophen poisoning as their primary or secondary discharge diagnosis were identified using the International Classification of Diseases codes 965.4 (9th revision, poisoning by aromatic analgesic) and T39.1 (10th revision, poisoning by nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics, and antirheumatics [4-aminophenol derivatives]). A single investigator trained one to three medical record reviewers per city until a percentage agreement of 80% or greater and an interreviewer κ > 0.8 were established on a random subset of at least 50 records per reviewer. Medical record reviewers were blinded to the study hypothesis. Accuracy of data collection was assessed by independent review of the first 100 charts for each data abstractor, followed by quarterly database assessment for the duration of data collection. Data was collected from paper medical records for the entire study period (July 1997 to November 2005), which predated the widespread adoption of electronic medical records. The primary objective of this medical record review was to obtain a comparable number of patients treated with the 21-h IV NAC protocol to compare outcomes to those treated with the 72-h oral NAC protocol. Further details on the design, selection of participants, definitions, and data collection of the Canadian Acetaminophen Overdose Study have been described previously [14].

For the purposes of the current study, patients were selected from the larger dataset if they were treated initially with the 21-h IV NAC protocol, regardless of ingestion type or whether the extrapolated 4-h acetaminophen concentration was above or below the Rumack-Matthew nomogram line. Subjects were deemed to have been treated initially with the 21-h IV NAC course of therapy when it had been ordered as a 150 mg/kg infusion over 15 to 60 min, followed by 50 mg/kg over 4 h, and finally 100 mg/kg over 16 h, consistent with the approved product label in Canada (the label specifies a loading dose over 15 min). Actual treatment durations less than or greater than 21 h were retained, but patients initially treated with NAC regimens other than the 21-h IV protocol (e.g., 48 h IV, 72 h oral) were excluded.

Study Definitions

Chart abstractors were trained to identify potential adverse reactions to NAC by thorough review of the available medical records, including emergency department physician and nursing notes, consultations, admission history and physical, orders, inpatient records, and discharge summaries. An anaphylactoid reaction was defined as the presence of any of the following during the NAC infusion: documentation in the medical record of the words “anaphylactic,” “anaphylactoid” or “allergic reaction”; urticaria (any variant of the word “rash”); pruritus (any variant of the word “itchy”); hypotension (adults: systolic ≤ 90 mmHg or a decrease of ≥ 40 mmHg; pediatrics (age < 18): systolic ≤ 70 + (age in years × 2) mmHg); edema (angioedema, swelling of the lips, tongue, and/or around eyes); respiratory symptoms (cough, wheeze, stridor, shortness of breath, chest tightness, respiratory distress, or bronchospasm); or death attributed to NAC. Reactions were classified as cutaneous (yes/no) if the reaction included urticaria, pruritus, and/or edema, and as systemic (yes/no) if the clinical features included respiratory symptoms or hypotension [2]. We did not collect data on asthma, atopy, family history of allergy, and previous reactions to IV NAC during the medical record review; therefore, we were unable to study the effect of these risk factors on the development of an anaphylactoid reaction.

Anaphylactoid reactions were deemed absent when none of the above terms were mentioned on the data collection form. Nausea or vomiting was not deemed per se to represent an anaphylactoid reaction. The infusion rate of NAC during which the reaction began, the duration of initial loading dose, and any treatment of the reaction including temporary or permanent discontinuation of the infusion were documented. Finally, any medications administered to treat the anaphylactoid reaction were also extracted from the medical record. These medications were classified into one of four categories: antihistamines, beta-agonists, corticosteroids, or epinephrine.

Acetaminophen ingestions were classified as acute (either single ingestion taken at a known time consistently reported in the medical record, or when the ingestion window including the most extreme discrepant times in the medical record was ≤ 8 h) or chronic (ingestion over > 8 h). The highest measured (peak) acetaminophen concentration was identified from all concentrations obtained. For all acute ingestions, the first post-4 h serum acetaminophen concentration was also identified using any measurements obtained at least 4 h but no more than 24 h after an acute ingestion, and converted to a 4-h equivalent concentration assuming a 4-h elimination half-life. When the time of ingestion was not a single moment in time or not consistently reported, the time of ingestion was taken to be the earliest possible time of the ingestion window, as per usual clinical practice.

Outcome

Because reactions differ in severity, the primary outcome was a three-level ordinal variable ranked by increasing severity: no reaction, cutaneous only, and any systemic reaction. We also examined as secondary outcomes each reaction type as binary variables: any anaphylactoid reaction (yes/no), any systemic reaction (yes/no), and any cutaneous reaction (yes/no).

Data Analysis

Serum acetaminophen concentrations were logarithmically transformed, as were time intervals given the substantial positive skew. For univariate comparisons of these continuous measures between the three mutually exclusive reaction groups (no reaction, cutaneous only, and any systemic reaction), the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test on the untransformed natural scale measures was used to confirm the findings of the parametric analysis based on comparing the log-transformed means via ANOVA. In the primary analysis, the three-level outcome of reaction severity was modeled using mixed-direction stepwise multivariable logistic regression with a threshold for addition to the model of 0.1 and for removal of 0.05. We considered each of the following candidate predictor variables: age, sex, ingestion type, peak acetaminophen, first post-4 h acetaminophen, dose reportedly ingested, interval from ingestion to NAC, and ethanol coingestion. In separate secondary analyses, the binary variables by reaction type were also modeled using the same candidate predictors and model construction.

Results

Of 11,987 hospital admission records in the primary study database, 1037 were excluded because their chart was not available for review, 3487 because they did not receive NAC, and 1008 because a NAC protocol other than the 21-h IV was started. Thus, 6455 patients all initially treated with the 21-h IV NAC protocol were included in this study. Of these patients, 136 died, including 34 who did not exhibit clinical signs of hepatotoxicity and 16 who underwent liver transplantation. Less than 3% of patients were enrolled prior to 1988, and we consistently identified more than 300 cases a year treated with the 21-h IV NAC protocol from 1992 to 2005. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of this group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Characteristic | Result (n = 6455) |

|---|---|

| Age, years [IQR] | 24 [17, 37] |

| Female (%) | 4457 (69.0) |

| APAP ingestion type (%): | |

| Acute ingestion at single, known time | 3496 (54.2) |

| Acute ingestion at inconsistently reported time | 1739 (26.9) |

| Chronic ingestion (ingestion over > 8 h) or time unknown | 1220 (18.9) |

| Peak (highest measured) APAP concentration, μg/mL [IQR] | 126 [50.8, 197] |

| First post-4 h APAP concentrationa, μg/mL [IQR] | 103 [37.8, 175] |

| Time from ingestion to above APAP concentrationa, h [IQR] | 8.4 [5.0, 18] |

| Equivalent 4 h APAP concentrationa, μg/mL [IQR] | 244 [154, 606] |

| Rumack-Matthew nomogram risk zone (%): | |

| ≥ 500 μg/mL | 477 (7.4) |

| 400 μg/mL to < 500 μg/mL | 233 (3.6) |

| 300 μg/mL to < 400 μg/mL | 477 (7.4) |

| 200 μg/mL to < 300 μg/mL | 899 (13.9) |

| 150 μg/mL to < 200 μg/mL | 715 (11.1) |

| < 150 μg/mL | 798 (12.4) |

| Not measured between 4 and 24 h | 1636 (25.3) |

| Not applicable (chronic/time unknown) | 1220 (18.9) |

| Time from ingestion to start of NAC, h [IQR] | 9.3 [6.2, 19] |

| Dose of APAP reportedly ingested, g [IQR] | 15 [6.5, 30] |

| Ethanol co-ingested (%) | 1848 (28.6) |

| Alcoholic (%) | 1417 (30.0) |

| Total duration of NAC therapy (%): | |

| Less than 20 h | 516 (8.0) |

| 20 to 21 h | 4872 (75.5) |

| Greater than 21 h | 1067 (16.5) |

| NAC therapy interrupted (%): | 274 (4.2) |

| Peak aminotransferase (AST or ALT) recorded, IU/L | 31 [20, 87] |

Continuous measures are shown as the median and interquartile range [IQR]

APAP acetaminophen, NAC N-acetylcysteine

aFirst post-4-h APAP concentration, times from ingestion, and subsequent nomogram-based transformations are undefined for chronic/time unknown ingestions or when obtained outside the 4- to 24-h window post ingestion

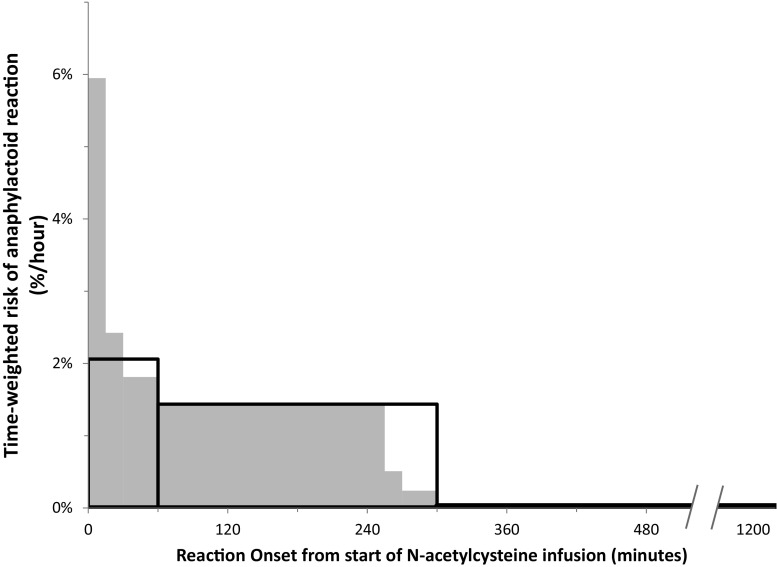

Anaphylactoid reactions were reported in 528 (8.2%) patients, of whom 398 (75.4%) manifested only cutaneous involvement. Three-hundred and seventy-one (70.3%) reactions were first noted during the second infusion phase of NAC (i.e., 50 mg/kg over 4 h) and 133 (25.1%) during the first infusion (i.e., 150 mg/kg over 15–60 min). Of the patients who developed reactions during the first infusion, 75 (56.4%) had received the loading dose administered over 15 min. After adjusting for the duration of the phase of infusion, the time-weighted risk was highest during the first phase, i.e., > 2%/h using the most conservative estimate of a 60-min duration for the first infusion compared to 1.4%/h during the second phase and 0.03%/h during the third. This time-weighted risk was even higher when the effect of shorter loading phases was incorporated into the analysis under the very conservative assumption that a shorter loading phase was not associated with an increase in anaphylactoid reactions (Fig. 1). The NAC infusion was stopped either temporarily or permanently in 274 (51.9%) cases. There were no fatalities attributed to NAC. Altogether, 403 (76.3%) patients received at least one medication for treatment of anaphylactoid reactions, mostly antihistamines (371, 92.1%). Further descriptions of the reactions are listed in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Time-weighted risk of developing an anaphylactoid reaction during the three phases of intravenous N-acetylcysteine infusion. The absolute risk for experiencing a reaction during each of the three dosing phases (150 mg/kg over 15 to 60 min, 50 mg/kg over 4 h, 100 mg/kg over 16 h) is shown, divided by the duration of the phase. Thus, the area of each rectangle is proportional to the actual number of cases. The large, open rectangles bounded by solid lines show the risk had all patients been administered the loading dose over 60 min and is therefore a very conservative estimate of the risk rate during the loading phase. The gray rectangles show a closer (yet also conservative) approximation under the null hypothesis that the risk of reaction is independent of the duration of the loading phase

Table 2.

Description of reactions

| Characteristic | Result (n = 6455) |

|---|---|

| Any anaphylactoid reaction (%) | 528 (8.2) |

| Type of reaction (%): | |

| Cutaneous only | 398 (6.2) |

| Systemic only | 34 (0.5) |

| Both cutaneous and systemic | 96 (1.5) |

| NAC dosing phase in progress at reaction onset (%): | |

| First (150 mg/kg 15–60 min) | 133 (2.1) |

| Second (50 mg/kg over 4 h) | 371 (5.7) |

| Third (100 mg/kg over 16 h) | 24 (0.4) |

| Duration of first (loading) phase in patients experiencing reaction during this phase (%): | |

| 15 min | 75 (1.1) |

| 30 min | 26 (0.4) |

| > 30 min | 32 (0.5) |

| NAC infusion interrupted or discontinued | 274 (4.2) |

| Medications administered for anaphylactoid reaction (%): | |

| Antihistamines | 371 (5.7) |

| β2-agonists | 15 (0.2) |

| Epinephrine | 10 (0.2) |

| Corticosteroids | 7 (0.1) |

| Any medication | 403 (6.2) |

NAC N-acetylcysteine, IQR interquartile range

Table 3 compares the characteristics of patients by the primary outcome of reaction severity (i.e., none, cutaneous only, or systemic). Risk factors of patients who developed more severe reactions included age, female sex, and no coingestion of ethanol. In addition, the measured acetaminophen concentrations were lower in patients with more severe reactions, and the time interval from ingestion to treatment with NAC was substantially longer, especially in patients with systemic reactions. Thus, the extrapolated 4-h equivalent acetaminophen concentrations as calculated by the nomogram (which estimate the ingested dose by incorporating the delay postingestion) were more similar between groups, being only slightly higher in patients with no reaction.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients classified by reaction type

| Characteristic | No reaction (n = 5927) | Cutaneous reaction only (n = 398) | Any systemic reaction (n = 130) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [IQR] | 24 [17, 37] | 22 [17,32] | 22 [18,34] | < 0.001 |

| Female (%) | 4056 (68.4) | 301 (75.6) | 100 (76.9) | 0.002 |

| Acute ethanol ingestion, no. (%) | 1713 (28.9) | 91 (23.7) | 30 (23.1) | 0.03 |

| Acute ingestion at single, known time (%) | 3158 (53.3) | 262 (65.8) | 76 (58.5) | < 0.001 |

| First post-4 h APAP concentration, μg/mL [IQR] | 106 [40.5177] | 95.0 [23.4, 157] | 42.8 [11.4, 90.9] | <0.001 |

| Equivalent 4 h APAP concentration, μg/mL [IQR] | 248 [156, 617] | 206 [144, 387] | 223 [134, 866] | 0.002 |

| Time from ingestion to start of NAC, h [IQR] | 9.2 [6.2, 19] | 9.6 [6.2, 21] | 15 [8.3, 27] | < 0.001 |

Continuous measures are shown as the median and interquartile range [IQR] while discrete data are shown as count (percentage)

Table 4 describes the results of the logistic regression analysis of predictor variables. The factors that were independently associated with a more severe reaction were being female; having overdosed at a single, known, and consistently reported time; and having a lower measured serum acetaminophen concentration. While these associations were statistically significant, the strength of association was rather weak, with adjusted odds ratios near one. These factors, and the strength of the associations, were consistent across the secondary models by reaction type. In this analysis, age, first post-4 h [APAP], dose of APAP reportedly ingested, time from ingestion to start of NAC, and coingestion of ethanol were not associated with a more severe reaction.

Table 4.

Multivariable modeling of association between anaphylactoid reaction type and patient characteristic. Each modeled outcome is shown as a separate row. Odds ratios [95% confidence intervals] are shown for an increase in severity of reaction (i.e., any systemic reaction vs. cutaneous only vs. no reaction for the multilevel primary model; yes vs. no for the binary secondary models) for each factor remaining in the final model (i.e., after adjustment for all factors); therefore, an odds ratio < 1.0 signifies a lower likelihood of reaction/severity. APAP concentrations were logarithmically transformed, and the odds ratios shown denote the odds ratio associated with a doubling of the measure

| Model | Female | Acute ingestion at single, known time | Peak (highest measured) [APAP] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any systemic vs. cutaneous only vs. no reaction (primary model) | 1.24 [1.08, 1.42] | 1.24 [1.10, 1.39] | 0.79 [0.68, 0.92] |

| Any systemic vs. no systemic reaction | NS | NS | 0.72 [0.50, 1.04] |

| Any cutaneous vs. no cutaneous reaction | 1.23 [1.07, 1.43] | 1.21 [1.06, 1.37] | 0.81 [0.70, 0.93] |

| Any vs. no reaction | 1.23 [1.07, 1.42] | 1.23 [1.09, 1.38] | 0.79 [0.68, 0.92] |

NS not significant at P = 0.05 (i.e., removed from final model)

Discussion

In this large, national cohort of acetaminophen overdose patients, anaphylactoid reactions occurred in about one in 12 (8.2%) treatment courses when using the traditional 21-h IV NAC protocol. Most reactions were cutaneous, and only one in 50 (2.0%) treatment courses reportedly exhibited respiratory effects and/or hypotension. Almost all reactions were noted during the first 5 h of IV NAC. Patients who developed reactions had lower measured serum acetaminophen concentrations. Our data suggest that the acetaminophen concentrations were lower primarily due to longer time intervals from ingestion to presentation, rather than being due to a smaller ingested dose per se. To our knowledge, this cohort is by far the largest reported in the literature with respect to the incidence of anaphylactoid reactions to IV NAC for any indication.

Our findings with regard to the time of adverse reaction onset are concordant with prior studies [4, 11, 16, 17] and with pharmacokinetic models estimating serum NAC concentrations to be much higher during the first few hours of the traditional infusion protocol [13]. In our study, the total number of reactions was highest during the second phase of IV NAC, similar to the findings of Waring et al. [8]. However, since the first or loading phase is considerably shorter than the second (1 h or less versus 4 h), and given any non-zero delay to the recognition of the reaction, the reaction risk rate is actually highest during the loading phase. Similarly, the substantial number of reactions occurring during the first phase when it is at its shortest (i.e., 15 min rather than 60) suggest that the risk rate is substantially higher when this loading dose is given quickly. We did not record the duration of the loading phase in patients not having a reaction during that phase and cannot easily estimate when Canadian physicians moved from the 15- to the 60-min load as our cohort spans 25 years. As a result, we cannot explicitly test the hypothesis that a longer infusion phase is associated with a lower risk of anaphylactoid reactions. Nevertheless, the compelling and dramatic fall in the time-weighted risk parallels the front-end heavy-dosing protocol and corroborates the widely held notion that administering the loading dose over 60 min is associated with a lower incidence and/or less severe reactions to IV NAC.

Kerr et al. found no difference in the incidence of reactions to IV NAC when the loading dose (150 mg/kg) was given over 15 versus 60 min [11]. However, this study has been criticized for lack of power, confounding by co-ingested medications, and lack of blinding. A systematic review by Brok and colleagues reported that administering the infusion of the first dose of NAC over 60 min resulted in reduced odds of any NAC-associated adverse event (including both anaphylactoid and non-anaphylactoid reactions) [18]. A subsequent randomized trial of a shorter infusion protocol with a slower initial load (100 mg/kg over 2 h, then 200 mg/kg over 10 h) has shown fewer adverse effects including anaphylactoid reactions and especially vomiting or retching [12]. Investigators in Australia have reported fewer adverse effects compared to historical controls when using a so-called two-bag schedule (200 mg/kg over 4 h followed by 100 mg/kg over 16 h) [19] [20].

Another group reported their experience with a different two-bag schedule in which the first infusion was slowed even further when patients present shortly after acute overdose. In that study, patients were also empirically administered NAC based primarily on history pending initial laboratory test results [21]. The investigators concluded that empirical administration based on dose reportedly ingested led to an unacceptably high rate of reactions as most patients did not ultimately need treatment. The study also summarized the adverse reactions from prior prospective human studies, pointing out heterogeneity in the classification of these reactions.

Taken in this context, our results and the absence of any known clinical benefit for a faster infusion rate suggest that the loading dose should not be given faster than over 60 min. Indeed, slower infusions should continue to be explored and the collective experience compared to the incidence rates reported herein and by others. We hope that this report provides a relevant benchmark of the risk of cutaneous or systemic reactions to the 21-h IV NAC protocol, with clear and reproducible methodology that can be used to test the safety and tolerability of alternative NAC dosing schedules. Importantly, standardization in the identification and grading of adverse effects with regard to severity should be sought to allow meaningful comparisons, in addition to testing for efficacy [22].

Others have previously noted that lower acetaminophen concentrations and increasing time from ingestion to NAC treatment are risk factors for anaphylactoid reactions (4,8,9). Acetaminophen itself may exert a protective effect, possibly by inhibition of multiple cyclo-oxygenase enzymes [8]. Our findings suggest that the increasing time delay to NAC is not an independent risk factor, but rather results in patients having a lower acetaminophen concentration due to endogenous clearance over time. In fact, after adjusting for time of serum acetaminophen sampling after single, acute overdose, the estimated 4-h acetaminophen concentrations are remarkably similar between groups, suggesting that any protective effect of acetaminophen is not determined by the ingested dose but rather the remaining parent drug concentration in circulation at the time NAC is started.

Management guidelines for anaphylactoid reactions to IV NAC were proposed many years ago by Bailey and McGuigan [1]. Their guidelines recommend no specific treatment and no change in the NAC infusion if the only symptom is flushing; diphenhydramine 1 mg/kg intravenously for urticaria; diphenhydramine and holding the infusion for 1 h for angioedema; and diphenhydramine, holding the infusion, and consideration of ephedrine for respiratory symptoms or hypotension. If no symptoms reappear after 1 h after stopping the infusion, they recommended that the NAC infusion be restarted. Pretreatment with an antihistamine may also be considered in patients who have previously developed reactions (10). In our study, most patients who were treated with a medication received an antihistamine. Over half of our patients also had their NAC infusion stopped either temporarily or permanently. We did not attempt to adjudicate whether any of these actions were, in fact, appropriate.

There have been reports of patients developing fulminant liver failure and undergoing hepatic transplantation when NAC was inappropriately discontinued after an anaphylactoid reaction [23]. While administration of IV NAC is not without risk, our results suggest that when anaphylactoid reactions occur, they result in primarily cutaneous symptoms, and fatalities are rare. Given the low incidence of reactions in our study, and the ability to easily treat these reactions should they occur, we believe that IV NAC remains an extremely safe antidote for acetaminophen poisoning.

We encourage clinicians to verify the need for NAC prior to resuming the infusion, but not to withhold the antidote should it in fact be warranted. NAC is often administered empirically when patients present late, or despite serum acetaminophen concentrations below the treatment line of the nomogram, yet these patients are at higher risk for adverse reactions to the intravenous administration of NAC by virtue of having lower serum concentrations of acetaminophen. For otherwise asymptomatic patients presenting late or reporting a chronic ingestion in whom laboratory testing will be delayed, the loading dose might even be administered orally if the likelihood of requiring NAC appears to be less than the risk of a systemic anaphylactoid reaction. However, this approach will need to be studied in order to evaluate its usefulness.

Our study has several limitations. While we had hoped to study the contribution of potential patient risk factors such as asthma, atopy, family history of allergy, previous reactions to IV NAC, as well as the effect of resuming IV NAC in patients who developed a reaction, these data were not abstracted from the medical records and were therefore not available for analysis. Since the data collection was retrospective, we were dependent on the information contained within the medical record. As a result, direct comparison with adverse event rates noted during clinical trials or other prospective studies is not advisable. Our dataset was created using hospitalized patients and did not include patients treated and discharged from the emergency department. However, during the study period, the vast majority of patients treated with intravenous NAC in Canada were admitted to hospital. We only collected data on the duration of the loading phase when patients had a reaction during this phase. This limits our ability to formally test for an association between adverse reactions and rate of infusion. Finally, our database covered the time period from February 1980 to November 2005. We acknowledge the time delay from completion of data collection to presentation of results in abstract form, more comprehensive data analysis, and finally publication of results. With this in mind, there have not been substantive changes in either the administration or the formulation of IV NAC in Canada since 2005; therefore, we are confident that despite the time interval, our results remain applicable to current practice.

Conclusion

In this cohort of hospitalized patients treated initially with the 21-h IV NAC protocol for acetaminophen poisoning, the incidence of anaphylactoid reactions was low. Most reactions were noted during the first few hours of treatment and involved only cutaneous symptoms. Patients who developed reactions were more likely to be female, to have taken an acute overdose, and to have a lower acetaminophen concentration compared to those who did not develop a reaction. While these associations are relevant for understanding the underlying mechanism of this adverse drug effect, they are not strong enough to impact the current clinical decision-making surrounding initiation of NAC.

Sources of Funding

No funding was received for this study

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: Table 4 in PDF version of this article has been corrected since the original publication of the article because the first column of numbers (under the heading “Female”) in the original PDF version was typeset poorly so that the numbers could not be correctly interpreted.

Preliminary abstract presented at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians Annual Scientific Assembly, June 2009, Calgary, Alberta

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-018-0657-5.

Change history

3/12/2018

The original article has been corrected. Table 4 in PDF version of this article has been corrected since the original publication of the article because the first column of numbers (under the heading “Female”) in the original PDF version was typeset poorly.

References

- 1.Bailey B, McGuigan MA. Management of anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31(6):710–715. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70229-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kao LW, Kirk MA, Furbee RB, Mehta NH, Skinner JR, Brizendine EJ. What is the rate of adverse events after oral N-acetylcysteine administered by the intravenous route to patients with suspected acetaminophen poisoning? Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):741–750. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(03)00508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandilands E, Bateman DN. Adverse reactions associated with acetylcysteine. Clin Toxicol. 2009;47(2):81–88. doi: 10.1080/15563650802665587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch RM, Robertson R. Anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine: a prospective case controlled study. AccidEmergNurs. 2004;12:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gheshlaghi F, Eizadi-Mood N. Atopic diseases: risk factor in developing adverse reaction to intravenous N-acetylcysteine. J Res Med Sci. 2006;11(2):108–110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K. Risk factors in the development of adverse reactions to N-acetylcysteine in patients with paracetamol poisoning. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51:87–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appelboam AV, Dargan PI, Knighton J. Fatal anaphylactoid reaction to N-acetylcysteine: caution in patients with asthma. Emerg Med J. 2002;19(6):594–595. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.6.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waring WS, Stephen AF, Robinson OD, M a D, Pettie JM. Lower incidence of anaphylactoid reactions to N-acetylcysteine in patients with high acetaminophen concentrations after overdose. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46(6):496–500. doi: 10.1080/15563650701864760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pakravan N, Waring WS, Sharma S, Ludlam C, Megson I, Bateman DN. Risk factors and mechanisms of anaphylactoid reactions to acetylcysteine in acetaminophen overdose. ClinToxicol. 2008;46:697–702. doi: 10.1080/15563650802245497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt LE. Identification of patients at risk of anaphylactoid reactions to N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of paracetamol overdose. ClinToxicol. 2013;51(6):467–472. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.799677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr F, Dawson A, Whyte IM, Buckley N, Murray L, Graudins A, et al. The Australasian clinical toxicology investigators collaboration randomized trial of different loading infusion rates of N-acetylcysteine. AnnEmergMed. 2005;45(4):402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman DN, Dear JW, Thanacoody HK, Thomas SH, Eddleston M, Sandilands EA, et al. Reduction of adverse effects from intravenous acetylcysteine treatment for paracetamol poisoning: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):697–704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiew AL, Isbister GK, Duffull SB, Buckley NA. Evidence for the changing regimens of acetylcysteine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;81(3):471–481. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarema MC, Johnson DW, Berlin RJ, Sivilotti ML, Nettel-Aguirre A, Brant RF, et al. Comparison of the 20 hour intravenous and the 72 hour oral acetylcysteine protocols in the treatment of acute acetaminophen poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(4):606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman DN, Carroll R, Pettie J, Yamamoto T, Elamin M, Peart L, et al. Effect of the UK’s revised paracetamol poisoning management guidelines on admissions, adverse reactions and costs of treatment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(3):610–618. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mant TG, Tempowski JH, Volans G, Talbot JC. Adverse reactions to acetylcysteine and effects of overdose. BMJ. 1984;289(6439):217–219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6439.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson AH, Henry DA, McEwen J. Adverse reactions to N-acetylcysteine during treatment for paracetamol poisoning. Med J Aust. 1989;150(6):329–331. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brok J, Buckley N, Gluud C. Interventions for paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003328.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wong A, Graudins A. Simplification of the standard three-bag intravenous acetylcysteine regimen for paracetamol poisoning results in a lower incidence of adverse drug reactions. Clin Toxicol. 2016;54(2):115–119. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1115055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNulty R, Lim J, Chandru P, Gunja N. Fewer adverse effects with a modified 2-bag intravenous acetylcysteine protocol compared to the traditional 3-bag protocol in paracetamol overdose. Clin Toxicol. 2017;55(5):1–4. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1408812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isbister GK, Downes MA, Mcnamara K, Berling I, Whyte IM, Page CB. A prospective observational study of a novel 2-phase infusion protocol for the administration of acetylcysteine in paracetamol poisoning. Clin Toxicol. 2016;54(2):120–126. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1115057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bateman DN, Dear JW, Thomas SH. New regimens for intravenous acetylcysteine, where are we now? Clin Toxicol. 2015;3650(January):1–4. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1121545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pizon AF, LoVecchio F. Adverse reaction from use of intravenous N-acetylcysteine. J Emerg Med. 2006;31(4):434–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]