Abstract

Introduction

There has been increasing interest in the availability of non-prescription benzodiazepines and their sale as new psychoactive substances. We wanted to determine UK availability from Internet suppliers and motivations for use of three benzodiazepines (diclazepam, flubromazepam, and pyrazolam).

Methods

In November 2014 and March 2016, using the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Snapshot Methodology, Internet search engines (google.co.uk, uk.yahoo.com and ask.com.uk) were searched using the terms ‘buy diclazepam’, ‘buy flubromazepam’ and ‘buy pyrazolam’. Threads from drug-user forums (bluelight.org, drugs-forum.com, erowid.org, legalhighsforum.com) were analysed using a general inductive approach. Data were converted into price per gram/pellet to allow cost comparisons and to determine motivations for use.

Results

There was an increase in websites selling these benzodiazepines between 2014 and 2016: diclazepam (49 in 2014 to 55 in 2016), pyrazolam (33 to 35), and flubromazepam (39 to 45). Thirty-eight (63.3%) sites were based in the UK/Europe. Drugs were sold as pellets (49 websites, 81.7%), powder (19, 31.7%), and blotters (1, 1.7%). Pill forms were not available, and one (1.7%) website sold diclazepam/flubromazepam in liquid form. The cost reduced with increasing purchase quantities. Main motivations for use included anxiolysis, management of benzodiazepine withdrawal, sedation/sleep aid, and management of stimulant withdrawal.

Conclusions

These three benzodiazepines are widely available online, most commonly as pellets, and are (mis)used for a number of reasons. This study could be used to support triangulation of data from other sources to inform harm minimisation strategies.

Keywords: New psychoactive substances, Benzodiazepines, Diclazepam, Flubromazepam, Pyrazolam

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, there have been an increasing number of new psychoactive substances (NPS) being sold through the Internet [1–4]. Most recently, this market has evolved to include a number of benzodiazepines that are not registered as medicinal products in Europe. Initial NPS-benzodiazepines available in the UK included etizolam and phenazepam in 2010 although these are legally prescribed elsewhere in the world, such as Japan and Russia, respectively [5–7]. There have been reports of acute toxicity and deaths associated with recreational use of phenazepam in the UK resulting in its classification as a class C schedule 2 drug under the UK Misuse of Drugs Act, 1971 in 2012 [8, 9]. Table 1 demonstrates examples of drugs that have been classified within schedule 2 of this Act [10].

Table 1.

Schedule 2 of the UK Misuse of Drugs Act, 1971, classifies drugs according to their therapeutic usefulness, potential for abuse, diversion and the perceived need for control, into categories A, B and C. Category A is associated with the highest degree of potential harm. Non-authorised manufacture, possession and supply could result in imprisonment and monetary penalties

| Class A | Heroin, methadone, cocaine, crack, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, methamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, N,N-dimethyltryptamine and psilocybin mushrooms |

| Class B | Amphetamine, barbiturates, cannabis, synthetic cannabinoids, cathinone derivatives, codeine, ketamine, methoxetamine and methylphenidate |

| Class C | Gamma-hydroxybutyrate and gamma-butyrolactone, diazepam, flunitrazepam and most other tranquillisers, anabolic steroids, khat and benzylpiperazine |

Phenazepam has also been subject to control in a number of other European countries, such as Sweden and Germany [11]. Since 2012/2013, there have been reports to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) Early Warning System (EWS) of the availability of NPS-benzodiazepines, diclazepam, flubromazepam and pyrazolam, not only in the UK, but also from a number of other European countries including Germany, Norway, Luxembourg, Italy, Denmark, Hungary, Finland, Sweden and Poland [12].

Diclazepam, pyrazolam, and flubromazepam were investigated in drug candidate research studies in the 1960s and 1970s [13–15] but were never registered or marketed as medicinal products in Europe. More recently, there have been studies that have investigated the pharmacokinetics of these drugs in humans and also their analytical detection in a range of biological matrices [16–18]; however, currently, there is limited data on their potential for acute toxicity, prevalence of use or availability. There have been anecdotal reports of their availability from Internet sites selling other new psychoactive substances [12], but there have been no systematic studies investigating their availability on the Internet. Using established recognised EMCDDA snapshot methodology [19, 20], we investigated the availability of diclazepam, flubromazepam, and pyrazolam from Internet suppliers and undertook a qualitative review of user discussion forums to understand motivations for their use. These three benzodiazepines were selected as they were the first non-controlled benzodiazepines reported to the EMCDDA [21]. Since June 2017, diclazepam, flubromazepam, pyrazolam, and etizolam have been registered as class C schedule 2 drugs under the UK Misuse of Drugs Act, 1971 [22].

Methodology

Using the EMCDDA methodology [19, 20], an Internet snapshot survey for the availability and pricing of these benzodiazepines was initially undertaken in November 2014 and then repeated in March 2016 to determine any changes over time in their availability. The Internet search engines ‘google.co.uk’, ‘yahoo.co.uk’, and ‘ask.com.uk’ were searched in English using the search terms ‘buy diclazepam’, ‘buy flubromazepam’, and ‘buy pyrazolam’.

Sampling was undertaken to exhaustion for each search term, whereby the first 100 Internet sites identified were reviewed in full to understand their content and then sampling continued until 20 consecutive unrelated sites were identified. Information was collected on the number of sites offering each of these drugs for sale and accessible to the UK market, the form of the drug and the cost. The origin of the Internet site was determined by either the listed physical address on the Internet site or a claim where the main site of operations/supply was available in the nominated country(s). The place of manufacture of drugs was determined by similar specific claims on the Internet site, where this information was available.

The cost of each benzodiazepine was then converted into cost—British Pound (GBP)—per gram for powder or cost per pellet/pill/blotter to allow comparison across different purchase quantities. For the purposes of the study, pills are defined as any solid dosage form of the drug, pellets are spherical particulates manufactured by the agglomeration of fine powders/granules [23] and blotters are highly absorbable paper often perforated to micro-tabs with impregnated liquid doses of drugs [24]. The advertised formulations were not purchased to test the manufacturer’s claim. Where Internet sites provided costs in US Dollars or Euros, the amounts were converted to GBP for comparison using the European Budget Commission Internet site and daily conversion currency conversion rates at the time of use [25]. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel® 2007 and SPSS® version 21 and presented as frequency and percentages. Continuous data are non-parametric and presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and compared using Mann-Whitney U test. Kruskall-Wallis test was performed to test for differences between the range of price per weight of NPS-benzodiazepines. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages and compared by Fisher’s exact test. p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

To understand drug-users’ motivation for purchasing (and using) these emerging benzodiazepines, a review was undertaken of the drug-user forums bluelight.org, drugs-forum.com, erowid.org and legalhighsforum.com. These sites have been previously identified as leading sources of online information on NPS [26]. In March 2016, these open access sites were searched using the terms ‘diclazepam’, ‘pyrazolam’, and ‘flubromazepam’. All yielded threads were reviewed. Information relating to motivation were analysed using a general inductive approach [27] and compiled in a Microsoft Excel® 2007 document. This involved close reading of the text, which was carried out by two members of the evaluation team, specific text segments related to the objectives were identified and this information was coded into basic elements. These were then narrowed down to reduce overlap and redundancy [27]. This sought to identify recurrent patterns of experience as coded elements which were then reorganised into overarching themes.

This study did not require Institutional Review Board approval [28]. Data was collected through pre-existing publicly available datasets from anonymous users, and there was no direct intervention or interaction with forum discussions or members.

Results

Internet Sites Selling Diclazepam, Flubromazepam and Pyrazolam

The initial snapshot survey (November 2014) revealed a total of 55 Internet sites selling these drugs (49 selling diclazepam, 39 selling flubromazepam, and 33 selling pyrazolam). All three drugs were available from 24 sites and various combinations of two of the three drugs from 16 sites. The remaining 15 sites were selling only one drug. The search engine ‘google.co.uk’ provided the complete list of Internet sites identified; whilst there was some overlap between Internet suppliers on ‘yahoo.com.uk’ (39 sites) and ‘ask.com.uk’ (28 sites), these search engines did not provide any new Internet sites to those identified through ‘google.co.uk’. The subsequent snapshot survey (March 2016) identified an increase in websites per NPS-benzodiazepines, there were 60 identified websites overall with 55 websites selling diclazepam (33 new, 60%), 35 websites selling pyrazolam (19 new, 54.3%), and 45 selling flubromazepam (28 new, 62.2%). All three drugs were available from 31 Internet sites and various combinations of two of the three drugs from 15 Internet sites. The remaining 14 sites were selling only one drug. The search engine ‘google.co.uk’ provided the majority of Internet sites overall; however, in the latter snapshot survey, both ‘yahoo.com.uk’ (35 Internet sites, 10 new sites) and ‘ask.com.uk’ (16 sites, 1 new site) provided additional Internet sites not found on previous search engine searches.

A range of concentrations and purchase quantities advertised for each form of the drug was available. In November 2014, the drugs were sold in various forms including pellets (50 Internet suppliers, 90.9%), powder (10, 18.2%), blotters (2, 3.6%), and pills (1, 1.8%); a breakdown of Internet sites for each drug is shown in Table 2. One Internet site sold all three in blotter form (diclazepam (2.5 mg per blotter), flubromazepam (2.5 mg per blotter), and pyrazolam (1.5 mg per blotter) in purchase quantities ranging from 10 to 1000 blotters. Diclazepam and flubromazepam were available in pill form and sold from one Internet site only, in quantity ranges of 50 pills (one bottle) to 2000 pills (one zip bag).

Table 2.

Variable drug forms and dose strengths of novel benzodiazepines sold by Internet suppliers in November 2014 and March 2016

| Benzodiazepine | Date | Number of Internet suppliers | % Internet suppliers originating from the UK | Dose form, quantity purchase range and median prices per pellet/powder quantity over this range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellets: dose form in milligrams (number of pellets available) | Powder: number of grams available | Blotters: dose form in milligrams (number of blotters available) | Pills: dose form in milligrams (number of pills available) | Solution: dose form in milligrams (number of milliliters available) | ||||

| Diclazepam | November 2014 | 49 | 67.3% (33) | 1, 2 (1–100,000) | 0.05–50 | 2.5 (10–500) | 1 (50–2000) | None available |

| March 2016 | 55 | 52.7% (29) | As above | 0.05–1000 | None available | None available | 2.5 mg/ml 10–100 |

|

| Flubromazepam | November 2014 | 39 | 64.1% (25) | 4, 5, 8 (1–100,000) | 0.05–50 | 2.5 (10–1000) | 4 mg (50–2000) | None available |

| March 2016 | 45 | 51.1% (23) | 4, 5, 8, 10 (1–100,000) | 0.05–1000 | As above | None available | 5 mg/ml 10–100 |

|

| Pyrazolam | November 2014 | 33 | 75.8% (25) | 0.5, 1 (1–100,000) | 0.05–2 | 1.5 (10–1000) | None available | None available |

| March 2016 | 35 | 62.9% (22) | As above | 0.05–50 | 1.5 (500) | None available | None available | |

By March 2016, drugs were no longer available for sale in pill form, but liquid solution was now available for diclazepam and flubromazepam (2.5 and 5 mg/ml for 10–100 ml purchase quantities, respectively) from one (1.7%) Internet supplier; other forms available were pellets (49 websites, 81.7%), powder (19, 31.7%) and blotters (1, 1.7%) (Table 2). Also, whilst pellet purchases remained very similar to November 2014, powder was available in larger 1 kg quantities for diclazepam and flubromazepam (Table 2).

Supplier’s Country of Origin

Of the 55 Internet sites identified in November 2014 selling these drugs, most appeared to originate from the UK (34, 61.8%), elsewhere in Europe (7, 12.7%), in both the UK and elsewhere in Europe (3, 5.5%) and the USA (2, 3.6%). The origin of the remaining nine Internet sites (16.4%) was not readily identifiable. Five (9.1%) Internet sites listed the countries of manufacture. One Internet site listed diclazepam production in the UK, and another Internet site listed diclazepam production in Europe, India, and China. Two Internet sites listed both flubromazepam and diclazepam production in China, Hong Kong, and Europe. One Internet site selling pyrazolam and flubromazepam only cited manufacture across Europe and Asia. There was no significant change in the sites that specified their origin/manufacture in the second snapshot survey in March 2016, the majority still being based in the UK (30, 50%). The remaining had various origins: Europe (8, 13.3%), USA (7, 11.7%), China (5, 8.3%), India (1, 1.7%), Canada (1, 1.7%), and unknown (8, 13.3%).

Pricing of NPS-Benzodiazepines

Currency

In the initial snapshot survey of 55 Internet sites, the majority (48, 87.3%) of Internet sites quoted prices in GBP, five (9.1%) quoted prices in Euros and two (3.6%) in US dollars. By March 2016, a slightly higher proportion of Internet sites were marketed in non-GBP currency (combined Euros and US dollars) with 44 (74%) Internet sites being in GBP versus 6 (10%) that quoted prices in Euros and 10 (16%) in US dollars. However, this was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.068).

Change in Cost with Bulk Purchase

Price per Gram Powder

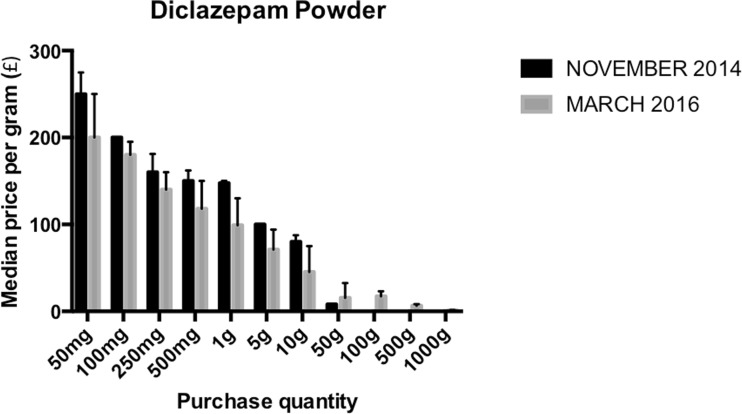

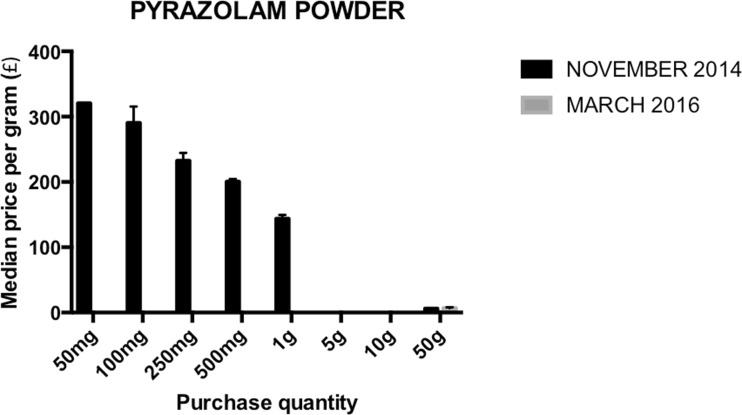

In both years studied, the cost of diclazepam and flubromazepam powder was lower when purchasing in bulk (limited suppliers for pyrazolam powders prevented the analysis) (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

Price per gram for different purchase quantities of diclazepam powder found in the Internet snapshot surveys. In November 2014, the median cost per gram of diclazepam powder reduced from £249.9 (£224.85–£274.95) for 50 mg purchase quantities to £8.10 per gram for 50 g (one supplier) purchase quantities. Median (IQR) and Kruskal-Wallis test were performed on diclazepam powder data for November 2014 purchase quantities of 100 mg (n = 4, £200 [£200–£200]), 1 g (n = 6, £147.5 [£99.75–£150]) and 10 g (n = 4, £80 [£80–£87.5]) (p value < 0.001) and March 2016 purchase quantities of 100 mg (n = 6, £180 [£120–£195]), 1 g (n = 9, £99 [£56.79–£130]) and 10 g (n = 7, £45.44 [£32.89–£75.18]) (p value < 0.0054)

Fig. 2.

Price per gram for different purchase quantities of pyrazolam powder found in the Internet snapshot surveys. The median cost per gram of pyrazolam powder reduced from £320.00 (one supplier) for 50 mg purchase quantities to £5.80 (one supplier) for 50 g powder purchase quantities. A comparison of price/gram of pyrazolam powder purchase quantities within each snapshot survey and between time points could not be performed due to limited data for November 2014 and March 2016

Fig. 3.

Price per gram for different purchase quantities of flubromazepam powders found in the Internet snapshot surveys. Flubromazepam median cost per gram of powder reduced from £249.9 (£224.85–£274.95) for 50 mg purchase quantities to £58.5 (£58.50–£67.50) for 10 g purchase quantities. Median (IQR) and Kruskal-Wallis test were performed on flubromazepam powder data for November 2014 purchase quantities of 100 mg (n = 3, £215 [£165–£215]), 1 g (n = 4, £100 [£99–£100]) and 10 g (n = 3, £58.5 [£58.5–£67.5]) (p value < 0.0004) and March 2016 purchase quantities of 100 mg (n = 5, £180 [£180–£250]), 1 g (n = 10, £100 [£67.34–£116.25]) and 10 g (n = 7, £48 [£32.47–£64.8]) (p value < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in price/gram of powder over the two surveyed time points (Mann-Whitney test, 100 mg, p = 0.420 and 10 g, p = 0.364)

Price per Pellet

There was a statistically significant reduction in price/pellet for diclazepam, pyrazolam and flubromazepam with increasing purchase quantities within each snapshot survey (data shown in the Appendix).

Change in Cost over Time

Price per Gram Powder

The price/gram of NPS-benzodiazepine powder over the two surveyed time points was compared using a convenience sample of low and high powder purchase quantities—100 mg and 10 g of powder. The difference in price over time achieved statistical significance at higher purchase quantities for diclazepam powder only (Mann-Whiney test 100 mg, p value 0.291 versus 10 g, p value = 0.046) (see Figs. 1, 2 and 3). The availability of 1000 g of diclazepam powder was not noted in November 2014.

Price per Pellet

There was a statistically significant difference in cost over time for large purchase quantities of pyrazolam pellets only (Appendix). There was a decrease in prices for 10,000 pellets between November 2014 (9 websites) versus March 2016 (7) (p = 0.04). A total increase of Internet sites selling the pellet form of pyrazolam (November 2014, n = 31 and March 2016, n = 31) was not simultaneously shown.

Motivation for the Use of NPS-Benzodiazepines

Overall, we identified 333 posts on the discussion forums, which included content on the motivation of use (pyrazolam—152 posts; diclazepam—137 posts; flubromazepam—44 posts). There was overlap within some posts discussing more than one of the studied drugs or more than one reason for use was identified within the same post. General inductive analysis of identified posts revealed seven main themes regarding the benzodiazepines overall. In order of frequency, these were anxiolysis (134 coded elements), tapering benzodiazepines/management of benzodiazepine withdrawal (55), sedation/sleep aid (55), management of stimulant withdrawal (51), euphoria (21), ability to function during use (19), and muscle relaxation (11). Other minor themes included use to combat alcohol withdrawal (6), opioid withdrawal (4), calm a ‘trip’ (4), increased sociability (4), unavailability of preferred benzodiazepine supply (3), low cost (3), combat vasoconstriction (1), chronic pain (1), and solubility (1), which are shown in Table 3. There was some variation between motivations for use of pyrazolam, flubromazepam, and diclazepam. Pyrazolam was favoured for anxiolysis whilst diclazepam was preferred for sedation/sleep aid and both diclazepam and flubromazepam were frequently cited for treatment of benzodiazepine withdrawal.

Table 3.

Main themes associated with motivations of use of benzodiazepines diclazepam, flubromazepam and pyrazolam

| Diclazepam | Pyrazolam | Flubromazepam | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Anxiolysis | 37 | 23.9 | 87 | 53.0 | 10 | 10.2 | 134 |

| Ability to function during use | 3 | 1.9 | 14 | 8.5 | 2 | 2.0 | 19 |

| Euphoria | 5 | 3.2 | 10 | 6.1 | 6 | 6.1 | 21 |

| Management of stimulant withdrawal | 25 | 16.1 | 17 | 10.1 | 9 | 9.2 | 51 |

| Tapering benzodiazepines/management of benzodiazepine withdrawal | 35 | 22.6 | 4 | 2.4 | 16 | 16.3 | 55 |

| Sedation/sleep aid | 32 | 20.6 | 18 | 11.0 | 5 | 5.1 | 55 |

| Muscle relaxant | 4 | 2.6 | 4 | 2.4 | 3 | 3.1 | 11 |

| Other | 14 | 9.0 | 10 | 6.1 | 3 | 3.1 | |

| Alcohol withdrawal | 2 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 2.0 | 6 |

| Opioid withdrawal | 2 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.2 | 4 | ||

| Calm a ‘trip’ | 2 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.2 | 4 | ||

| Increased sociability | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Unavailability of preferred benzodiazepine supply | 3 | 2.0 | 3 | ||||

| Inexpensive | 3 | 2.0 | 3 | ||||

| Combat vasoconstriction (MPA use) | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | ||||

| Chronic pain | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | ||||

| Soluble route | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | ||||

n refers to the number of elements indicating a motivation of use (more than one motivation could exist in a single post). This exceeded the total individual posts for all three drugs (pyrazolam—164 elements, diclazepam—155 elements, flubromazepam—54 elements)

Discussion

We have shown in this study that these three NPS-benzodiazepines are available to potential UK users from numerous Internet sites and that it is possible to purchase them in bulk quantities with decreasing cost per unit. This trend in the pricing of NPS has been similarly observed in previous Internet snapshot studies using EMCDDA methodology for other new psychoactive substances such as alpha-methyltryptamine, 4,4′-dimethylaminorex and methiopropamine [2–4].

The Office for National Statistics General Household Survey in 2007 revealed 0.5% of the UK population had used a ‘tranquiliser’ in the last year. Data regarding benzodiazepine dependence in the UK has not been directly measured, however is estimated that between 0.5 and 1.5 million people are benzodiazepine dependent based on general practice prevalence surveys of long-term users (greater than 6 months) [29, 30]. According to the National Treatment Agency, 4% (n = 1254) of all drug misuse clients have sought specific treatment relating to benzodiazepine use as the ‘primary drug’ of dependence, and this has been stable as a relative proportion of clients seeking help compared with 2013–2014 (4%, n = 5806). A relatively high prevalence of adjunct benzodiazepine use is noted, 11% (n = 16,103), in those who present with opiate misuse as a ‘primary drug’ problem [31].

In 2016, there were 406 drug poisoning deaths involving benzodiazepines in the UK, the highest number registered since 1993 when records commenced [32]. Only 17 of these involved benzodiazepines where no other drug was mentioned—diazepam (7) and temazepam (3), the remaining benzodiazepines were not listed [32]. There has been a steady increase in the deaths attributed to new psychoactive substances-benzodiazepine analogues that have been recorded on the death certifications from 2011 (2) to 2016 (10); 44 deaths in total have been recorded [32]. Most recently, some of the NPS-benzodiazepines including diclazepam and flubromazepam have been listed as co-ingestants in mortality case profiles analysing other ‘legal highs’ such as MT-45 (an opioid analgesic drug) [33]. There is one published case report of co-use of diclazepam with an amphetamine-like substance in a young male who presented to an Emergency Department in France; however, predominant sympathomimetic effects were observed and the significance of the co-ingested diclazepam is not clear [34]. The National Programme on Substance Abuse Deaths (NPSAD) collects data that is voluntarily submitted by coroners in England and demonstrated a total of 25 instances where an NPS-benzodiazepine was implicated in the cause of death—diclazepam (3), pyrazolam (1), and flubromazepam (7)—from 2013 to 2016 [35]. All NPS-benzodiazepines reported were found in combination with other drugs; detectable opiates were present in over half the cases [35]. There have been studies indicating the increased risk of death due to augmented risk of upper airway obstruction/respiratory depression with concomitant benzodiazepine use particularly with other sedative drugs [36].

There is little data regarding NPS-benzodiazepine use amongst the UK population. Of the 7326 UK respondents to the 2013/2014 Global Drug Survey, 12.4% reported last year prevalence of a ‘benzodiazepine’, although this did not specify the benzodiazepine used or the method of procurement. This is the most recent published data on benzodiazepine use in spite of more recent surveys in 2015 and 2016. Within the UK respondents in the 2013/2014 Global Drugs Survey, approximately one fifth (22.1%) of respondents reported that they had ever bought ‘drugs’ over the Internet, the highest proportion in comparison with all other countries surveyed; there was no differentiation on the substance(s) bought over the Internet [37]. The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) describes illicit sedative use amongst youths in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. This was last performed in 2011 around the advent of drug detection in Europe. Six per cent of UK respondents reported prescription use of sedatives or tranquilisers compared to 3% without a doctor’s order. This was within the lower prevalence ranges as compared with other European countries. The survey did not make specific reference to the benzodiazepine class of drugs and the type of benzodiazepines obtained by respondents [38]. UK data was not supplied in the most recent 2015 ESPAD report [39].

There is accumulating information on Internet user discussion forums on experiences with these drugs. Recreational doses have been estimated to be between 0.5 and 4 mg for pyrazolam, 4 and 12 mg for flubromazepam, and 1 and 2.5 mg for diclazepam for non-dependent users [40–42]. Therefore, the large amounts available for individual purchases, which can include up to 100,000 pellets or 1 kg of powder, suggest they are being sold not only for individual use, but also potentially for sharing amongst friends and/or distribution through street-level drug dealing.

Most of the seizures of these NPS-benzodiazepines reported to the EMCDDA were in tablet form [43], in contrast to the majority (94.5%) of Internet sales advertised in pellet form and only one site (1.8%) offering the drugs in pill form (2014 only). From a drug enforcement perspective, the most commonly seized class C drug in 2016/2017 was benzodiazepines with 1945 seizures; the total quantity of benzodiazepines seized in 2016/2017 (567,438 doses) was more than double that in 2015/2016 (246,544) in the UK [44]. However, a breakdown of type was not supplied in the report. It is possible that pills/tablets may be labelled as ‘pellets’ on Internet sites in an attempt to avoid medicinal marketing regulations. This has been seen with other new psychoactive substances sold on Internet sites [2]. Additionally, a range of diclazepam content from 0.59 to 1.39 mg compared to the 1 mg declared on the online shop was analytically confirmed in the study pills [18]. This may explain the limited effects observed by some first-time users of pyrazolam and diclazepam who reported repeated use when no immediate effects were initially observed [42, 45].

Overall, the most prominent themes regarding motivations for use were anxiolysis (“if they are purely anti anxiety then thats what im looking for”) [46], sedation/sleep aid (“I am unable to sleep at night… so I use flubro at night”) [47], tapering benzodiazepines (“Right now I’m just trying to avoid withdrawals”), and ‘come down’ following the use of amphetamines, cocaine or other stimulants (“I am going to use the diclazepam for sleep after I take the MPA”) [45]. The primary appeal of pyrazolam was its anxiolytic properties [42] and particularly its cited ability to remain ‘functional’ during use. On the other hand, diclazepam and flubromazepam were popular for their long half-life, which was felt to make it an effective agent for tapering off benzodiazepines and a sleep aid. Some consumers have suggested that flubromazepam has a greater ‘euphoric’ effect but has resulted in prolonged fatigue over days [41]. In pharmacokinetic studies, diclazepam was observed to have an approximate elimination half-life of 42 h [18] and pyrazolam 17 h (it was noted that this was 3-fold longer than the half-life listed on the vendor Internet site the tablets were bought from) [17]. Flubromazepam had a half-life of 106 h [16], and this is considerably longer than other benzodiazepines in therapeutic use such as diazepam (20–100 h) [48] and other NPS-benzodiazepines such as phenazepam (60 h) [49]. Such long unanticipated half-lives in these three benzodiazepines and variation in content may place users at risk of significant adverse events such as overdose.

The main limitation to our study is that products were not purchased to determine the actual contents and formulation of the drugs sold. This is similar to other Internet snapshot surveys using EMCCDA methodology. It was not possible to confirm if websites indeed were vendors given the possibility of fraudulent sites. It is not possible to confirm the site of manufacture, and websites can be presented as originating from a particular country whilst operating from another. The 2016 EMCDDA drug report highlighted false advertising of illicit benzodiazepines; for example, seized diazepam tablets had been identified to contain phenazepam [50]. In the few studies reporting the pharmacokinetic profile of diclazepam, pyrazolam, and flubromazepam, tablets that were purchased over the Internet have contained the NPS-benzodiazepines in question [16–18].

Other Internet sources such as the ‘dark web’ were not explored. The ‘dark web’ is a portion of the deep web, a part of the Internet that is intentionally hidden and not accessible through standard web browsers. It requires additional software that can anonymise identity and is most widely known for illegal activity [51]. Whilst there is some stability in advertised supply over the two surveyed time points, the Internet NPS market has the potential to change rapidly within this timeframe and such tribulation will not be reflected in the survey. This study was undertaken in English only, and therefore it is possible that there may be other unidentified sites selling these benzodiazepines on non-English language Internet sites as well as user information. Further, drug-user motivation comments/posts reviewed were retrieved from forums that explicitly forbid discussion of vendors and general drug availability. Hence, it is not possible to extrapolate if motivation for use of NPS-benzodiazepines is related to ease of access/cost in light of Internet snapshot findings. There may be misattribution of drug effect and subsequent motivation to use in the context of poly-drug use; however, this is applicable to the interpretation of all user reports of recreational drug use. Individuals who post on drug-user forums may not be representative of all NPS users.

Conclusion

The online market of NPS-benzodiazepines diclazepam, flubromazepam, and pyrazolam is extensive in the UK. The most comprehensive list of vendors available was found through ‘google.co.uk’. NPS-benzodiazepines have increasingly been implicated in deaths secondary to drug poisonings particularly as lethal co-ingestants. This study is an important addition to toxicovigilance efforts of these three substances in the UK. The use of this methodology paves the way for future comparison studies to evaluate the impact of possible interventions around the control of these agents and understanding around patterns of use.

Appendix: Supplementary data regarding price per pellet of diclazepam, pyrazolam and flubromazepam with increasing bulk purchase and comparison of cost over the two surveyed time points

Change in Price/Pellet with Bulk Purchase

The median price per 1 mg diclazepam pellet in November 2014 reduced from £0.75 (£0.49–£1.00) for 10 pellets purchase quantities to £0.08 (£0.08–£0.10) for 10,000 pellets purchase quantities (KW p value < 0.0001), £1.00 (IQR £1.00–£1.20, for 10 pellets) to £0.20 (IQR £0.15–£0.35, for 10,000 pellets) (KW p value < 0.0001) for 4 mg flubromazepam pellets and from £1.00 (IQR £0.5–£1.00, for 10 pellets) to £0.14 (IQR £0.14–£0.22, for 10,000 pellets) (KW p value < 0.0001) for 0.5 mg pyrazolam pellets. In March 2016, the median price per pellet was £0.55 (IQR £0.5–£0.72, for 10 pellets) to £0.09 (IQR £0.09–£0.12, for 10,000 pellets) (KW p value < 0.0001) for 1 mg diclazepam pellets, £1.00 (IQR £0.80–1.08, for 10 pellets) to £0.15 (IQR £0.15–£0.17, for 10,000 pellets) (KW p value < 0.0001) for 4 mg flubromazepam pellets and from £0.6 (IQR £0.50–£0.81, for 10 pellets) to £0.13 (IQR £0.13–£0.13, for 100,000 pellets) (KW p value < 0.0001) for 0.5 mg pyrazolam pellet.

Change in Price/Pellet over Time

We compared advertised prices of a convenience sample of small and large purchase quantity of pellets—10 pellets and 10,000 pellets—for each benzodiazepine (median costs at these purchase quantities shown above). The purchase quantity of 10 pellets of 1 mg diclazepam pellets November 2014 (supplier number = 33) versus March 2016 (24) (Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.324) and 100,000 pellets (November 2014 (9) versus Mar 2016 (4): p = 0.258) did not significantly increase over time. This was also the case for pyrazolam 0.5 mg 10 pellet purchases from the November 2014 survey (25) versus March 2016 survey (20) (p = 0.086). Flubromazepam 4 mg pellets had no cost difference over the 10 pellet purchase quantity (November 2014 (26) versus March 2016 (28), p = 0.086) and 10,000 pellet purchase quantity (November 2014 (9) versus March 2016 (5), p = 0.193).

Sources of Funding

None

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The challenge of new psychoactive substances: A Report from the Global SMART Programme. 2013. Available from: http://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/NPS_2013_SMART.pdf (22 October 2016, date last accessed).

- 2.Wood DM, Dargan PI. Using internet snapshot surveys to enhance our understanding of the availability of the designer psychoactive substance alpha-methyltryptamine (AMT) Subst Use & Misuse. 2014;49:7–12. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.808224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermette-Marcotte AE, Dargan PI, Archer JR, Gosselin S, Wood DM. An Internet snapshot study to compare the international availability of the designer psychoactive substance methiopropamine. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014;52(7):678–681. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.933346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nizar H, Dargan PI, Wood DM. Using internet snapshot surveys to enhance our understanding of the availability of the designer psychoactive substance 4-methylaminorex and 4,4′-dimethylaminorex. J Med Toxicol. 2015;11(1):80–84. doi: 10.1007/s13181-014-0425-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iverson L. Letter to Minister of State for crime prevention and ASB reduction: phenezepam advice. Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD). 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/119184/acmd-advice-phenazepam.pdf Accessed 18 August 2016.

- 6.Maskell PD, De Paoli G, Nitin Seetohul L, Pounder DJ. Phenazepam: the drug that came in from the cold. J Forensic Legal Med. 2012;19(3):122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. World Health Organisation. Etizolam. Critical review report agenda item 4.13. Thirty-ninth Meeting Geneva, 6–10 November 2017. http://www.who.int/medicines/access/controlled-substances/CriticalReview_Etizolam.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2017.

- 8.Dargan PI, Davies S, Puchnarewicz M, Johnston A, Wood DM. First reported case in the UK of acute prolonged neuropsychiatric toxicity associated with analytically confirmed recreational use of phenazepam. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(3):361–363. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1361-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcel C. Explanatory memorandum to the misuse of drugs (designation) (Amendment No. 2) (England, Wales and Scotland) Order 2012 No. 1310 and the Misuse of Drugs (Amendment no.3) (England, Wales and Scotland) Regulation 2012 No. 1311. 2012. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1310/pdfs/uksiem_20121310_en.pdf. Accessed 20 August 2016.

- 10.Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Misuse of Drugs Act 197. 1971 c. 38. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1971/38/contents. Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 11.Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. World Health Organisation. Phenazepam pre-review report agenda item 5.8. Thirty-seventh meeting. Geneva, 16–20 November 2015. http://www.who.int/medicines/access/controlled-substances/5.8_Phenazepam_PreRev.pdf Accessed 16 August 2016.

- 12.EMCDDA. EMCDDA–Europol 2013 Annual report on the implementation of council decision 2005/387/JHA. 2013. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_229598_EN_TDAN14001ENN.pdf Accessed 16 August 2016.

- 13.Hester JB, Von Voigtlander P. 6-Aryl-4H-s-triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]-benzodiazepines. Influence of 1-substitution on pharmacological activity. J Med Chem. 1979;22:1390–1398. doi: 10.1021/jm00197a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sternbach LH, Fryer RI, Metlesics W, Reeder E, Sach G, Saucy G, Stempel A. Quinazolines and 1,4-benzodiazepines. VI.1a halo-, methyl-, and methoxy-substituted 1,3-dihydro-5-phenyl-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-ones1b,c. J Org Chem. 1962;27:3788–3796. doi: 10.1021/jo01058a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sternbach LH, Fryer RI, Metlesics W, Sach G, Stempel A. Quinazolines and 1,4-benzodiazepines. V. O-aminobenzophenones. J. Org. Chem. 1962;27:3781–3788. doi: 10.1021/jo01058a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moosmann B, Huppertz LM, Hutter M, Buchwald A, Ferlaino S, Auwärter V, et al. Detection and identification of the designer benzodiazepine flubromazepam and preliminary data on its metabolism and pharmacokinetics. J Mass Spectrom. 2013;48(11):1150–1159. doi: 10.1002/jms.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moosmann B, Hutter M, Huppertz LM, Ferlaino S, Redlingshöfer L, Auwärter V. Characterization of the designer benzodiazepine pyrazolam and its detectability in human serum and urine. Forensic Toxicol. 2013;31(2):263–271. doi: 10.1007/s11419-013-0187-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moosmann B, Bisel P, Auwärter V. Characterization of the designer benzodiazepine diclazepam and preliminary data on its metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Drug Test Anal. 2014;6(7–8):757–763. doi: 10.1002/dta.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillebrand J, Olszewski D, Sedefov R. Legal highs on the Internet. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:330–340. doi: 10.3109/10826080903443628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EMCCDA. Online sales of new psychoactive substances/‘legal highs’: Summary of results from the 2011 multilingual snapshots (Briefing paper). 2012. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_143801_EN_SnapshotSummary.pdf Accessed 22 October 2016.

- 21.EMCDDA. EMCDDA-Europol 2012 Annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA, 2012. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/734/EMCDDA-Europol_2012_Annual_Report_final_439477.pdf Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 22.Home Office. Guidance. List of most commonly encountered drugs currently controlled under the misuse of drugs legislation. Updated 1 June 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/controlled-drugs-list--2/list-of-most-commonly-encountered-drugs-currently-controlled-under-the-misuse-of-drugs-legislation. Accessed 26 November 2017.

- 23.Nyol S, Gupta M. Immediate drug release dosage form: a review. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2013;3(2):155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erowid, LSD Blotter Art gallery. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/lsd/lsd_images_gallery1.shtml Accessed 28 November 2017.

- 25.European Commission. Budget. INFOREURO http://ec.europa.eu/budget/contracts_grants/info_contracts/inforeuro/inforeuro_en.cfm. Accessed 1 March 2016 and 25 November 2014.

- 26.Deluca P, Davey Z, Corazza O, Di Furia L, Farre M, Holmefjord Flesland L, et al. Identifying emerging trends in recreational drug use; outcomes from the Psychonaut Web Mapping Project. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Health Service Research Authority. UK policy framework for health and social care research. V3.3. 7/11/2017. https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/uk-policy-framework-health-social-care-research/ Accessed 26 November 2017.

- 29.Ford C, Law F. Guidance for the use and reduction of misuse of benzodiazepines and other hypnotics and anxiolytics in general practice 2014. https://smmgp.org.uk/media/11962/guidance025.pdf Accessed 25 October 2016.

- 30.Reed K, Bond A, Witton J, Cornish R, Hickman M, Strang J. The changing use of prescribed benzodiazepines and z-drugs and of over-the-counter codeine-containing products in England: a structured review of published English and international evidence and available data to inform consideration of the extent of dependence and harm. King’s College London. 2011. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/ioppn/depts/addictions/research/drugs/benzodiazepinesz-drugsandcodeineproducts.aspx Accessed 25 October 2016.

- 31.Public Health England. Adult substance misuse statistics from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS). 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017. https://www.ndtms.net/Publications/downloads/Adult%20Substance%20Misuse/Adult-statistics-from-the-national-drug-treatment-monitoring-system-2016-17.pdf. Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 32.Office for National Statistics. Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2016 registrations. Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales from 1993 onwards, by cause of death, sex, age and substances involved in the death. Release date 2/08/2017. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2016registrations. Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 33.EMCDDA. EMCDDA–Europol joint report on a new psychoactive substance: 1-cyclohexyl-4-(1,2-diphenylethyl)piperazine (‘MT-45’). 2014. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_230615_EN_TDAS14007ENN.pdf Accessed 16 August 2016.

- 34.Grossenbacher F, Souille J, Djerrada Z, Passouant O, Gibaja V. Exposure to 5f-P22, 5 IAI and diclazepam: a case report. Clin Toxicol. 2014;52:365. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Part of: Drug misuse and dependency Advice on U-47,700, etizolam and other designer benzodiazepines. Published: 20 December 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/579352/ACMD_TCDO_Report_U47700_and_Etizolam_and_designer_benzodiazepines.pdf Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 36.Caplehorn JRM, Drumger OH. Fatal methadone toxicity: signs and circumstances, and the role of benzodiazepines. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26(4):358–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winstock A. The Global Drug Survey 2014 findings. 2014. http://www.globaldrugsurvey.com/facts-figures/the-global-drug-survey-2014-findings/ Accessed 1 November 2016.

- 38.Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlström S, Balakireva O, Bjarnason T, Kokkevi A et al. The 2011 European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) report. Substance use among students in 36 European countries. 2011. http://www.espad.org/Uploads/ESPAD_reports/2011/The_2011_ESPAD_Report_FULL_2012_10_29.pdf Accessed 15 June 2016.

- 39.The ESPAD Group. ESPAD Report 2015. Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. http://www.espad.org/sites/espad.org/files/TD0116477ENN_002.pdf Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 40.Bluelight.org (RC’s) 2′-chlorodiazepam (diclazepam) brand new benzo RC. 2014. http://www.bluelight.org/vb/threads/685248-2-chlorodiazepam-(diclazepam)-brand-new-benzo-RC/page17. Accessed 12 October 2016.

- 41.Bluelight.org. Flubromazepam. 2012. http://www.bluelight.org/vb/threads/654337-Flubromazepam Accessed 13 October 2016.

- 42.Drugs-forum.com. Drug info—pyrazolam drug info. 2012. https://drugs-forum.com/forum/showthread.php?t=190434. Accessed 5 October 2016.

- 43.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2017), European drug report 2017: trends and developments, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/4541/TDAT17001ENN.pdf Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 44.Broadfield D, Marshall J. Home Office. Seizures of drugs in England and Wales, financial year ending 2017 Statistical Bulletin 22/17. November 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/657872/seizures-drugs-mar2017-hosb2217.pdf Accessed 1 December 2017.

- 45.Drugs-forum.com. Drug info—diclazepam drug info. 2013. Available from: https://drugs-forum.com/forum/showthread.php?t=221967&page=2 Accessed 8 October 2016.

- 46.Bluelight.org. Thread: pyrazolam megathread http://www.bluelight.org/vb/threads/633714-Pyrazolam-Megathread Accessed 13 October 2016.

- 47.Bluelight.org. Thread: clonazepam as prescribed, Etiz & Flubro as occasional alternative? 2012. http://www.bluelight.org/vb/threads/741567-Clonazepam-as-prescribed-Etiz-amp-Flubro-as-occasional-alternative Accessed 13 October 2016.

- 48.Greenblatt DJ, Shader RI, Divoll M, Harmatz JS. Benzodiazepines: a summary of pharmacokinetic properties. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;11(Suppl 1):11S–16S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zherdev VP, Caccia S, Garattini S, Ekonomov AL. Species differences in phenazepam kinetics and metabolism. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1982;7(3):191–196. doi: 10.1007/BF03189565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.EMCDDA (2016). European drug report 2016. Trends and Developments, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg http://wwwemcddaeuropaeu/system/files/publications/2637/TDAT16001ENNpdf Accessed 29 November 2017.

- 51.EMCDDA (2016) The internet and drug markets, EMCDDA Insights 21, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/2155/TDXD16001ENN_FINAL.pdf Accessed 2nd March 2018.