Abstract

The influence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes in the natural history of the disease and its response to antiviral treatment have been addressed in many studies. In Brazil, studies on HBV genotype circulation have been restricted to specific population groups and states. Here, we have conducted a nationwide multicentre study with an unprecedented sample size representing all Brazilian regions in an effort to better understand the viral variants of HBV circulating among chronic carriers. Seven HBV genotypes were found circulating in Brazil. Overall, HBV/A was the most prevalent, identified in 589 (58.7 %) samples, followed by HBV/D (23.4 %) and HBV/F (11.3 %). Genotypes E, G, C and B were found in a minor proportion. The distribution of the genotypes differed markedly from the north to the south of the country. While HBV/A was the most prevalent in the North (71.6 %) and Northeast (65.0 %) regions, HBV/D was found in 78.9 % of the specimens analysed in the South region. HBV/F was the second most prevalent genotype in the Northeast region (23.5 %). It was detected in low proportions (7 to 10 %) in the North, Central-West and Southeast regions, and in only one sample in the South region. HBV/E was detected in all regions except in the South, while monoinfection with HBV/G was found countrywide, with the exception of Central-West states. Our sampling covered 24 of the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District and is the first report of genotype distribution in seven states. This nationwide study provides the most complete overview of HBV genotype distribution in Brazil to date and reflects the origin and plurality of the Brazilian population.

Keywords: HBV, genotypes, Brazil

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B still represents a significant global public health problem despite the availability of an effective preventive vaccine against the aetiologic agent of the infection, hepatitis B virus (HBV). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 240 million people worldwide are chronic carriers of HBV, an infection that represents an increasing risk of liver complications such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1, 2].

HBV features a unique replication strategy in which the production of new genomic DNA molecules is preceded by an RNA intermediate synthesized by reverse transcription. The lack of proofreading activity during this replication step yields high substitution rates in the genome, conferring an increased genetic variability to HBV than would be expected for a DNA virus [3].

Based on this genetic variability, HBV has been classified into eight genotypes (A–H) by divergences of more than 7.5 % in the entire genome sequences within each genetic group [4, 5]. More recently, two additional genotypes (I and J) were tentatively proposed [6, 7]. Although recent studies have shown that the distribution pattern of HBV genotypes is changing, especially in regions of the world with elevated migratory waves, in general these ten genetic groups have distinct geographical distributions [8, 9]. Genotype A has a worldwide distribution but is primarily found in Northern Europe, North America and sub-Saharan Africa. Genotypes B and C are preferably found in East and Southeast Asia, and Oceania. A worldwide distribution is also a characteristic of the genotype D strains, with higher prevalence being reported in European, Middle Eastern and Mediterranean countries. Genotype E is endemic to West Africa and is rarely found outside Africa, a pattern similar to that observed for genotypes F and H, whose geographic distributions are almost restricted to Central and South America. Genotype G is not restricted to a specific location and has been reported in samples from the USA, Mexico, France, Germany, Turkey, Brazil and Japan. The newly designated genotypes I and J were only detected in individuals from Vietnam and Japan, respectively [4, 10].

Brazil is a federal republic composed of a Federal District and 26 states that are distributed within five geographic regions (North, Northeast, Central-West, Southeast and South), each presenting socio-demographic, economic and cultural particularities. One of the main characteristics of the population as a whole is its aetiological plurality, with great miscegenation among the native population, European colonizers, descendants of African slaves and more recent immigration of individuals from European, Asian and African countries. Regarding the prevalence of HBV infection, different rates can be observed throughout the country. While Brazil is considered a country with low to intermediate prevalence of HBsAg carriers (less than 1 %) [11, 12], there are some areas of high endemicity for HBV infection like the Amazon basin and villages located in the South and Southeast regions [13].

Although studies regarding HBV genotype circulation in Brazil have been published, most are restricted to a particular state and to specific population groups. In addition, HBV genotype distribution is unknown in seven of the 26 Brazilian states, namely Amapá, Espírito Santo, Ceará, Minas Gerais, Paraíba, Sergipe and Roraima. This multicentre study included samples from 24 of the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District, including samples from capitals and from hundreds of cities countrywide, being the most comprehensive and representative overview of the circulation of HBV genotypes among chronic carriers in Brazil to date.

Results

Sampling, demographic characteristics and overall HBV genotype distribution

Among the 1004 samples included in the study, the proportion of samples from each Brazilian geographical region included in this nationwide overview of HBV genotype distribution roughly reproduces the proportion of the population living in the corresponding regions, with the exception of the South region, which was slightly under-represented in the total sample size. Regarding all 26 Brazilian states, only two states, Piauí and Rio Grande do Norte, both located in the Northeast region, had no samples included in the study. In relation to gender, of the 915 samples with available information, 58.7 % were from men. The mean age of the patients was 43.4±13.7 years with more than 50 % of the samples with available information being from individuals between 30 and 50 years old. Viral load was available for 919 samples and the majority (37.2 %) of them had values between 3.3 and 4.3 log, a range that requires continuous monitoring of the individual in order to evaluate the necessity of starting antiviral treatment. The distributions of demographic and virological characteristics according to geographic region of the study population are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and virological characteristics of the study population and distribution of HBV genotypes by geographic region.

| Brazilian regions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (n=211) | Northeast (n=217) | Central-West (n=87) | Southeast (n=394) | South (n=95) | Total (n=1004) | |

| Gender* | ||||||

| Female | 103 (52.3 %) | 78 (52.3 %) | 24 (33.8 %) | 136 (34.7 %) | 37 (38.9 %) | 378 (41.3 %) |

| Male | 94 (47.7 %) | 82 (47.7 %) | 47 (66.2 %) | 256 (65.3 %) | 58 (61.1 %) | 537 (58.7 %) |

| Age (years)* | ||||||

| <20 | 4 (2.3 %) | 4 (6.1 %) | 0 (0 %) | 7 (1.9 %) | 1 (1.2 %) | 16 (2.1 %) |

| 20–30 | 38 (22.0 %) | 14 (21.2 %) | 15 (21.4 %) | 54 (14.7 %) | 8 (9.4 %) | 129 (16.9 %) |

| 31–40 | 42 (24.3 %) | 23 (34.8 %) | 19 (27.1 %) | 95 (25.9 %) | 11 (12.9 %) | 190 (25.0 %) |

| 41–50 | 49 (28.3 %) | 11 (16.7 %) | 18 (25.7 %) | 91 (24.8 %) | 31 (36.5 %) | 200 (26.3 %) |

| 51–60 | 20 (11.6 %) | 10 (15.1 %) | 9 (12.9 %) | 75 (20.4 %) | 17 (20.0 %) | 131 (17.2 %) |

| >60 | 20 (11.6 %) | 4 (6.1 %) | 9 (12.9 %) | 45 (12.3 %) | 17 (20.0 %) | 95 (12.5 %) |

| Viral load*, † | ||||||

| <3.3 | 87 (44.4 %) | 54 (28.1 %) | 14 (22.9 %) | 71 (18.8 %) | 26 (28.3 %) | 252 (27.4 %) |

| 3.3–4.3 | 69 (35.2 %) | 75 (39.1 %) | 19 (31.2 %) | 137 (36.2 %) | 42 (45.6 %) | 342 (37.2 %) |

| >4.3 | 30 (15.3 %) | 47 (24.5 %) | 20 (32.8 %) | 132 (34.9 %) | 22 (23.9 %) | 251 (27.3 %) |

| >8 | 10 (5.1 %) | 16 (8.3 %) | 8 (13.1 %) | 38 (10.1 %) | 2 (2.2 %) | 74 (8.1 %) |

| Genotype | ||||||

| A | 151 (71.6 %) | 141 (65.0 %) | 50 (57.5 %) | 232 (58.9 %) | 15 (15.8 %) | 589 (58.7 %) |

| D | 30 (14.2 %) | 17 (7.8 %) | 23 (26.4 %) | 89 (22.6 %) | 75 (78.9 %) | 235 (23.4 %) |

| F | 23 (10.9 %) | 51 (23.5 %) | 9 (10.3 %) | 29 (7.4 %) | 1 (1.0 %) | 114 (11.3 %) |

| Others | 3 (1.4 %) | 6 (2.8 %) | 2 (2.3 %) | 31 (7.9 %) | 1 (1.0 %) | 41 (4.1 %) |

| Mixed | 4 (1.9 %) | 2 (0.9 %) | 3 (3.4 %) | 13 (3.3 %) | 3 (3.2 %) | 25 (2.5 %) |

*Data considering available information for each category.

†Log.

A total of 1004 serum samples were genotyped by INNO-LiPA HBV Genotyping (INNO-LiPA) assay (n=835) and by direct nucleotide sequencing (n=169). Seven HBV genotypes (A–G) were found circulating in Brazil. Overall, HBV genotype A was the most prevalent, being identified in 589 (58.7 %) samples, followed by genotypes D (235; 23.4 %) and F (114; 11.3 %). Genotypes E, G, C and B were found in minor proportions in 18, 13, 9 and 1 sample(s), respectively. Among the samples genotyped by INNO-LiPA assay, infection with more than one genotype (mixed infection) was detected in 25 samples (2.5 %).

Statistical analyses to evaluate the relationship between the most prevalent genotypes (A, D and F) and gender, age groups and viral load did not reveal any significant relationship.

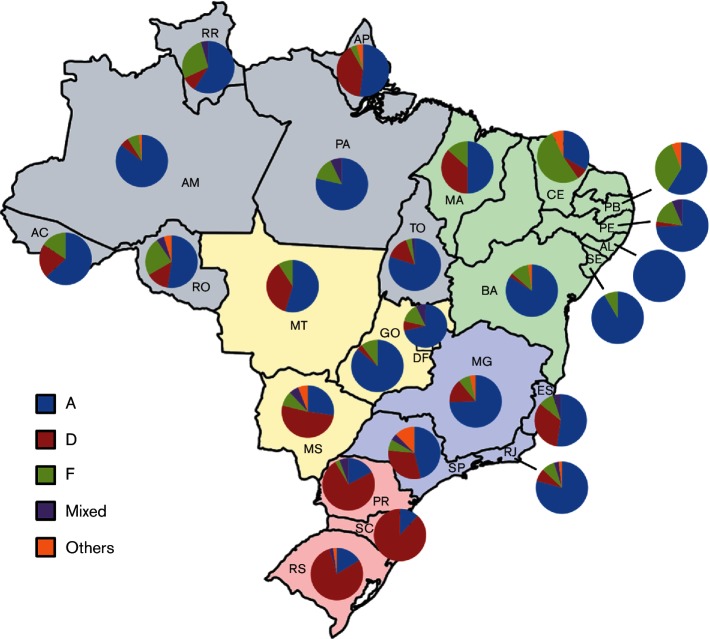

A distinct genotype distribution was found in the different states of the country (Fig. 1). The distribution of HBV genotypes A, D and F in the five Brazilian geographic regions indicated that HBV/A was the most prevalent in the North (151/211; 71.6 %), Northeast (141/217; 65.0 %), Central-West (50/87; 57.5 %) and Southeast (232/394; 58.9 %) regions (Table 1). An exception to this higher prevalence of genotype A was observed in the South region, where genotype D was found in nearly 80 % of the specimens analysed. HBV/D was the second most prevalent in the North, Central-West and Southeast regions, accounting for 14.2, 27.6 and 22.6 %, respectively, of total sampling in these regions. In relation to genotype F, a similarly low proportion (7 to 11 %) was found in samples from the North, Central-West and Southeast regions. This genotype was found in only one sample from the South region and had a high proportion (23.5 %) in the Northeast region, being the second-most prevalent after genotype A.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of HBV genotypes in Brazilian states. State abbreviations: North – AC, Acre; AM, Amazonas; AP, Amapá; PA, Pará; RO, Rondônia; RR, Roraima; and TO, Tocantins. Northeast – AL, Alagoas; BA, Bahia; CE, Ceará; MA, Maranhão; PB, Paraíba; PE, Pernambuco; and SE, Sergipe. Central-West – DF, Federal District; GO, Goiás; MT, Mato Grosso; and MS, Mato Grosso do Sul. Southeast – ES, Espírito Santo; MG, Minas Gerais; RJ, Rio de Janeiro; and SP, São Paulo. South – PR, Paraná; SC, Santa Catarina; and RS, Rio Grande do Sul.

A detailed distribution of the genotypes found in each state is presented in Table 2. The regional distribution of HBV genotypes per state indicated that differences in genotype frequency could be remarkable between states within the same geographic region. In the North region, HBV/A was the most prevalent in all states (Fig. S1, available in the online Supplementary Material), achieving proportions greater than 78 % in samples from Pará, Amazonas and Tocantins. Unlike other states, Amapá showed a high proportion of genotype D (40 %) and had a single case of monoinfection with genotype G. Genotype F was the second most common in Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia and Roraima. Two chronic carriers infected with genotype E were identified in Amazonas and Rondônia.

Table 2. HBV genotype distribution in HBsAg-positive samples according to locality.

| Location | n | Genotype distribution (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | Mix* | |||

| Brazil | 1004 | 589 (58.7) | 1 (0.1) | 9 (0.9) | 235 (23.4) | 18 (1.8) | 114 (11.3) | 13 (1.3) | 25 (2.5) | |

| Region | State | |||||||||

| North | 211 | 151 (71.6) | – | – | 30 (14.2) | 2 (0.9) | 23 (10.9) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Acre (AC) | 19 | 12 (63.2) | – | – | 4 (21.0) | – | 3 (15.8) | – | – | |

| Amapá (AP) | 25 | 13 (52.0) | – | – | 10 (40.0) | – | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.0) | – | |

| Amazonas (AM) | 55 | 47 (85.4) | – | – | 3 (5.4) | 1 (1.8) | 4 (7.3) | – | – | |

| Pará (PA) | 14 | 11 (78.6) | – | – | – | – | 2 (14.3) | – | 1 (7.1) | |

| Rondônia (RO) | 21 | 11 (52.4) | – | – | 3 (14.3) | 1 (4.8) | 5 (23.8) | – | 1 (4.8) | |

| Roraima (RR) | 22 | 13 (59.1) | – | – | 2 (9.1) | – | 6 (27.3) | – | 1 (4.5) | |

| Tocantins (TO) | 55 | 44 (80.0) | – | – | 8 (14.5) | – | 2 (3.6) | – | 1 (1.8) | |

| Northeast | 217 | 141 (65.0) | – | 2 (0.9) | 17 (7.8) | 2 (0.9) | 51 (23.5) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Alagoas (AL) | 26 | 26 (100) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Bahia (BA) | 44 | 37 (84.1) | – | – | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (11.3) | - | - | |

| Ceará (CE) | 57 | 19 (33.3) | – | 2 (3.5) | 4 (7.0) | 1 (1.7) | 30 (52.6) | 1 (1.7) | – | |

| Maranhão (MA) | 30 | 15 (50.0) | – | – | 11 (36.7) | – | 4 (13.3) | – | – | |

| Paraíba (PB) | 17 | 10 (58.8) | – | – | – | – | 6 (35.3) | 1 (5.9) | – | |

| Pernambuco (PE) | 31 | 23 (74.2) | – | – | 1 (3.2) | – | 5 (16.1) | – | 2 (6.4) | |

| Sergipe (SE) | 12 | 11 (91.7) | – | – | – | – | 1 (8.3) | – | – | |

| Central-West | 87 | 50 (57.5) | – | – | 24 (27.6) | 1 (1.1) | 9 (10.3) | – | 3 (3.4) | |

| Distrito Federal (DF) | 14 | 10 (71.4) | – | – | 1 (7.1) | – | 2 (14.3) | – | 1 (7.4) | |

| Goiás (GO) | 29 | 25 (86.2) | – | – | 1 (3.4) | – | 3 (10.3) | – | – | |

| Mato Grosso (MT) | 11 | 6 (54.5) | – | – | 4 (36.7) | – | 1 (9.1) | – | – | |

| Mato Grosso do Sul (MS) | 33 | 9 (27.3) | – | – | 18 (54.5) | 1 (3.0) | 3 (9.1) | – | 2 (6.1) | |

| Southeast | 394 | 232 (58.9) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.8) | 89 (22.6) | 13 (3.3) | 30 (7.6) | 9 (2.3) | 13 (3.3) | |

| Espírito Santo (ES) | 21 | 11 (52.4) | – | – | 7 (33.3) | – | 2 (9.5) | – | 1 (4.8) | |

| Minas Gerais (MG) | 55 | 41 (74.5) | – | – | 8 (14.5) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (7.3) | – | – | |

| Rio de Janeiro (RJ) | 101 | 80 (79.2) | – | – | 8 (7.9) | 1 (1.0) | 8 (7.9) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (3.0) | |

| São Paulo (SP) | 217 | 100 (46.1) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (3.3) | 66 (30.4) | 10 (4.6) | 16 (7.4) | 8 (3.7) | 9 (4.1) | |

| South | 95 | 15 (15.8) | – | – | 75 (78.9) | – | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Paraná (PR) | 35 | 6 (17.1) | – | – | 26 (74.3) | – | 1 (2.9) | – | 2 (5.7) | |

| Rio Grande do Sul (RS) | 43 | 7 (16.3) | – | – | 34 (79.1) | – | – | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Santa Catarina (SC) | 17 | 2 (11.8) | – | – | 15 (88.2) | – | – | – | – | |

*Mixed genotype infection: 11 A/G; 5 A/D; 3 D/F; 2 A/F; 2 A/B; 2 D/E.

A high predominance of genotype A could be observed in all Northeast states, with the exception of Ceará (Fig. S2). This genotype was found exclusively among samples from Alagoas and had substantial frequencies in Sergipe (91.7 %), Bahia (84.1 %) and Pernambuco (74.2 %). Genotype D was not frequently found in the Northeast region as a whole, having a considerable proportion only in Maranhão, infecting 36.7 % of the analysed samples. Genotype F was the major genotype circulating in Ceará (52.6 %) and found in 35.5 % of the samples from Paraíba. HBV genotypes C, E and G, not commonly detected in Brazil, were found in Ceará. Bahia had one case of genotype E infection and an HBV/G monoinfection was observed in Paraíba.

Regarding the Central-West region, in the Federal District and in Goiás, the great majority of samples was classified as HBV/A (71.4 and 86.2 %, respectively) while genotype D prevailed in Mato Grosso do Sul (54.5 %). Frequencies under 15 % were observed for HBV/F in the states from this region and only one infection with genotype E was found in Mato Grosso do Sul (Fig. S3).

In São Paulo, Brazil's most populated state, seven HBV genotypes (A–G) were detected circulating among chronic carriers. Genotypes A, D and F were most frequently observed (46.1, 30.4 and 7.4 %, respectively). São Paulo had 10 cases of HBV/E, eight monoinfections with HBV/G, seven HBV/C and one HBV/B. In Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, genotype A represented nearly 80 % of the analysed samples and Espírito Santo had the greatest proportion of genotype D (33.3 %) among the states of the Southeast region (Fig. S4).

In the South region, a high predominance of genotype D strains among the study population was observed (Fig. S5). This genotype was very frequent in all three states, representing 74.3 % of the samples from Paraná, 79.1 % from Rio Grande do Sul and 88.2 % from Santa Catarina. HBV/A prevalence ranged from 11.8 to 17.1 % and HBV/F was found in only one sample from Paraná. In Rio Grande do Sul, one sample characterized as a monoinfection with genotype G was detected.

Confirmation of INNO-LiPA results by direct sequencing and genotype-specific PCR assay

In order to confirm the reliability of HBV genotyping by LiPA, 85 samples genotyped using this methodology, including randomly selected samples and those characterized as genotypes not commonly reported in Brazil (genotypes B, C, E and H), were submitted to direct nucleotide sequencing to compare the results. Comparison between both methodologies indicated a 97.6 % (83/85) concordance of the results. The two samples with discordant results had been characterized by LiPA as genotype H. The phylogenetic analysis performed after the determination of the nucleotide sequences of these samples did not confirm this result, indicating that these samples were phylogenetically related to genotype D and F strains.

Also, a semi-nested PCR assay using HBV genotype G-specific primers was performed to confirm the high proportion (68/835; 8.1 %) of mixed infection with genotype G indicated by the INNO-LiPA assay results, especially the mixed infection of genotypes D/G and F/G, an unusual infection profile. Co-infection with genotypes D/G represented almost half (28/68; 41.2 %) of the total mixed infections found while co-infection with genotypes F/G was the second most commonly observed in 22.1 % of samples considered infected with more than one genotype. This result should be analysed with caution since further tests to confirm the presence of HBV/G using PCR primers specific for the characteristic 36 bp insertion in the genome of genotype G strains were negative. Furthermore, analysis of the electropherograms generated by nucleotide sequencing of available samples considered D/G or F/G by LiPA did not show any evidence of overlapping peaks that could suggest the occurrence of a mixed infection. Due to these observations, mixed infections D/G and F/G determined by INNO-LiPA seem to represent a methodology flaw with unspecific binding of the amplified PCR product of certain subgenotypes to the genotype G-specific probe, as discussed below. Aiming at a more accurate and likely scenario of HBV genotype distribution in Brazil, samples classified as mixed infection D/G or F/G were considered as monoinfection with genotypes D or F. Apart from these two mixed infections, co-infection with genotypes A and G was the most prevalent overall, identified in 11 samples. Further investigation by clonal analysis or next-generation sequencing (NGS) to confirm the mixed genotype infection determined by INNO-LiPA assay is warranted.

Discussion

The efforts of the Brazilian Ministry of Health in establishing a nationwide cooperation of nine public laboratories (Brazilian Hepatitis B Research Group) in a project conceived to trace an updated map of the genetic profile of HBV circulating among chronic carriers across Brazil resulted in a broad overview of the current situation in virtually all Brazilian states.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of HBV genotype distribution in seven Brazilian states: Amapá, Roraima, Ceará, Paraíba, Sergipe, Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais and in the Federal District of Brazil. With the exception of Ceará, genotype A was the major circulating strain in these states, with prevalence ranging from 52.0 % in Amapá to 91.7 % in Sergipe. A pronounced presence of HBV/F was observed in Ceará (52.6 %) and in Paraíba (35.3 %). Circulation of genotypes not commonly reported in Brazil was detected in Amapá (HBV/G), Minas Gerais (HBV/E), Paraíba (HBV/G) and Ceará (genotypes C, E and G). The knowledge of the circulation of HBV genotypes in these states provides relevant background information for future molecular epidemiological surveillance policies to identify and control viral dispersion, especially importation and dissemination of ‘foreign’ genotypes.

The overall HBV genotype distribution in Brazil reported here confirmed the preponderant circulation of genotypes A, D and F indicated by previous studies [14–18]. However, the overall prevalence of genotypes A (58.7 %), D (23.4 %) and F (11.3 %) found in the current study differed significantly (P<0.00001) from the proportion reported by Mello et al. (A: 48.5 %; D: 38.5 %; F: 13.0 %) in a study that also included samples from all Brazilian regions [17]. This discrepancy, which is more than that associated with a shift in the circulation of HBV strains in Brazil during the decade separating sampling, may reflect differences between the two studies in the study population (blood donors versus chronic carriers) and, mainly, the wide coverage of the present work with regard to sampling. Mello et al. [17] had limited access to samples from some geographic regions, which led to an extrapolation of results found in a single state capital to a region as a whole. Moreover, the previous study included samples from only nine Brazilian states. Here, we provide a robust sampling encompassing 24 of the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District, including not only samples from state capitals but also from hundreds of cities countrywide, making the results presented here the most accurate picture of the distribution of HBV genotypes described so far.

In addition to genotypes A, D and F, another four HBV genotypes were found to be circulating in Brazil in minor proportions. To our knowledge, only one previously published work reported the co-circulation of the main eight HBV genotypes in a single country. Osiowy et al. [19] identified, in a study with acute and chronic hepatitis B cases, HBV genotypes A–I circulating in Canada, a country that shares some similarities with Brazil, such as the continental dimensions of its territory and having immigrants of different nationalities [19]. It is interesting to note that, in our study, genotypes A–G were detected in a single state, São Paulo. It is Brazil's most populated state, has a large number of immigrant communities and is one of the main destinations of internal migratory flux in Brazil. The circulation of genotypes B, C and E is usually restricted to specific geographic regions (HBV/B and HBV/C in Eastern Asia and HBV/E in West Africa) [20] and there are only a few reports of its circulation in Brazil [15, 18, 21]. It is likely that these ‘foreign’ genotypes reflect the origin of the immigrants or the country where a Brazilian citizen acquired the virus, reinforcing the concept that HBV genotype might act as a valuable tool in the surveillance of viral spread. Regarding HBV genotype G, the least common throughout the world and usually found in co-infection with another genotype, our findings indicated the presence of 13 samples in monoinfection, a condition rarely reported in studies worldwide [22–24], which deserves further investigation to confirm the single genotype character of the infection.

Analysing the results of genotype distribution focusing on states per geographic region, previous studies carried out with samples from the North region reported a predominance of HBV/A in Acre, Amazonas, Pará and Tocantins [25–28], which was corroborated by our findings. A higher frequency of genotype D (45 %) compared to other states in the North region was observed in a study with HBsAg-positive pregnant women in Acre [29]. Here, although in a lower prevalence likely due to differences in the studied population, we also found a higher proportion of HBV/D samples in this state (21 %). However, it was in Amapá that a remarkable presence of genotype D (40 %) could be noticed. Since this higher frequency differs from that observed in neighbouring states, a refined characterization of the subgenotype level of D strains circulating in Amapá would be interesting to elucidate if its origin is related to internal migratory flux or the influence of its bordering country, French Guiana.

In Northeastern states, we found exclusively HBV/A in samples from Alagoas and frequencies over 74 % in Bahia, Sergipe and Pernambuco. A major circulation of this genotype had already been reported in previous studies with chronic carriers in Alagoas (92.5 %) [30] and Bahia (85.5 %) [21]. Heading to the northern portion of this region, we noticed an increase in the detection of HBV/F strains in Paraíba and especially in Ceará. A remarkably high prevalence of genotype F, a genotype typically found in Brazil's indigenous population, was found in Ceará state, where constant movement of individuals towards the Amazon region in search of temporary work in isolated areas can be noticed historically and could suggest greater contact with the Brazilian indigenous population. A recent manuscript describing HBV genotype distribution in Piauí reported genotype F as the second most prevalent genotype in the state, highlighting the tendency of finding this genotype in greater proportions in this part of the country [31]. Regarding genotype D, although its detection was low in the Northeast region as a whole (7.8 %), we found it circulating in 36.7 % of the samples from Maranhão. The presence of HBV/D in Maranhão had been reported earlier [32, 33] with a predominance of subgenotype D4 strains, considered an ancient and rarely reported subgenotype possibly related to an African origin [32, 34]. Interestingly, samples from Maranhão available in our study were genotyped by direct sequencing and demonstrated being closely related with D4 reference sequences, presumably related to the strong influence of African descendants in Maranhão's population.

Most of the studies conducted in the states in the Central-West region have been targeted to specific population groups such as injecting drug users [35], men who have sex with men [36], waste collectors [37] and HIV-positive patients [38, 39], impairing an appropriate comparison with our sampling. Despite this, these previous studies reported a greater incidence of HBV/A in Goiás and HBV/D in Mato Grosso do Sul, which was confirmed here. Genotype distribution in Federal District, geographically located inside the territory of Goiás, followed the findings from this state. The Central-West region is considered an area of late occupation in Brazil that received migratory fluxes from the South, Southeast and Northeast regions after the federal capital of Brazil moved to Brasília in 1960. Our results indicated that Goiás and the Federal District had a genotype distribution similar to that observed in the Southeast region while the higher frequency of HBV/D found in Mato Grosso do Sul might be related to its geographical proximity to the states in the South region.

The circulation of three main genotypes, A, D and F, has been demonstrated in the Southeast region since the first report on HBsAg subtype diversity in 1987 [40]. The higher prevalence of HBV/A, followed by HBV/D and HBV/F in smaller proportions, has been confirmed in several studies since then [14, 17, 41–47]. Here, we show for the first time the distribution of genotypes in two other states in the Southeast region, Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo. The main presence of the three genotypes was observed, with a significantly higher proportion of genotype D found in Espírito Santo when compared to Rio de Janeiro (P<0.005). This difference might be explained by the historical process of territorial occupation in Espírito Santo, where a large migratory contingent, mainly composed of Italians, has settled in the state since the 19th century [48]. In São Paulo, our findings indicated the circulation of HBV genotypes typically found in other parts of the world, as is the case for genotypes B and C in Asia and genotype E in West Africa. The identification of 12.4 % of samples with genotypes rarely found in Brazil agrees with the cosmopolitan character of São Paulo, a state that is home to diverse foreign communities of different ethnicities.

The relationship between HBV genotype and the ancestral origin of an infected individual is very evident when analysing samples from states in the South region. All three states were the destination of a large contingent of European immigrants, coming especially from Italy and Germany in the mid-20th century. This ancestral background is likely responsible for the very high prevalence of HBV/D found in Paraná (74.3 %), Rio Grande do Sul (79.1 %) and Santa Catarina (88.2 %), which is corroborated in the studies available in the literature [15, 49–51]. A genetic study based on mtDNA heritage also confirmed a greater influence of European origins in the population from the South region [52].

The method chosen for this study was the commercial assay ‘INNO-LiPA HBV Genotyping’ which has automated hybridization, scanner reading and strip interpretation, and standardization and reproducibility that allow the execution of tests in different laboratories around the country. This methodology is considered relatively simple, rapid and reliable, and has been used in other large-scale studies [19, 53]. One of the advantages highlighted by the commercial line probe assay manufacturer is the greater sensitivity of the test when compared to direct sequencing, which makes it capable of identifying minority viral populations. However, a limitation of methods based on reverse hybridization is that polymorphisms in the genomic region amplified for the hybridization with the immobilized probes may lead to unspecific binding and consequent misinterpretation of the result. Although previous studies had reported that INNO-LiPA was sensitive in detecting infection with more than one HBV genotype (mixed infection), especially genotypes A/B, A/C, A/G and B/C co-infection [53–55], our results showed an unexpectedly high proportion (8.1 %) of mixed infection determined by INNO-LiPA assay. Interestingly, the most detected co-infection was between genotypes D/G (28/68; 41.2 %) and F/G (15/68; 22.1 %), two genotype mixtures that have not been reported yet. Preliminary investigation using PCR amplification with genotype G-specific primers indicated that there was no evidence for the presence of HBV/G isolates co-infecting these samples. A possible unspecific ligation site in the INNO-LiPA probes, particularly the genotype G probe, with Brazilian strains of genotype D and F may have occurred. Knowing about such misinterpretation of the INNO-LiPA assay in certain HBV subgenotypes is important in diagnosis and clinical practice since some studies reported that the occurrence of a mixed genotype infection is related to a worse outcome and progression of the disease than a single genotype infection [56, 57]. In terms of genotype circulation, however, the assumption that mixed infections D/G and F/G were methodological artefacts would not greatly affect the overall genotype distribution.

This large-scale study had some limitations. Information about the ethnic background of the studied individuals would have been useful to establish a relation with the different genotypes found. Furthermore, demographic data was not available for all the samples and the cross-sectional nature of our study meant that the sampling included multiple scenarios regarding the stage of disease chronicity and management. The presence of untreated individuals along with patients under antiviral therapy for years or starting a rescue treatment with a new drug prevented the application of statistical analysis aiming to identify a relationship between certain genotypes and the outcome of disease.

The influence of the different HBV genotypes in the natural history of the disease and the response to antiviral treatment remains unclear [10]. Nonetheless, there is increasing evidence that HBV genotypes may be associated with a higher rate of progression to chronic infection and hepatocellular carcinoma, spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion, mutations in the precore and/or in basal core promoter, and response to interferon-based therapy [9]. Moreover, the genetic variability of HBV expressed in the different genotypes and its distinct distribution around the world and in relation to ethnic background make genotype classification a useful tool in epidemiological and transmission studies.

In this nationwide, multicentre study, our findings provide the most complete overview of HBV genotype distribution in Brazil to date, spanning virtually all Brazilian states and hundreds of cities countrywide. These data might contribute to molecular epidemiological surveillance of strains circulating in the country, assisting and supporting the strategic actions of the Ministry of Health to monitor and control viral dissemination.

Methods

Study population

In order to access the distribution of HBV genotypes across Brazil, a joint effort of nine public institutions representing all five regions of the country (North, Northeast, Central-West, Southeast and South) analysed serum samples from 1004 HBsAg-positive chronic hepatitis B carriers who attended public health care services between the years 2013 and 2015. Federal District and all Brazilian states except Piauí and Rio Grande do Norte, located in Northeast region, were represented in sampling that included individuals not only from state capitals but also several cities countrywide. The number of samples analysed in each state is given in Table 2.

Viral DNA extraction

HBV DNA was isolated from serum samples using the Biopur Mini Spin Viral DNA Extraction Kit (Biometrix Diagnostica, Paraná, Brazil) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Viral DNA was recovered in 50 µL of elution buffer and stored for further application to HBV genotyping using two strategies: (i) commercial line probe assay INNO-LiPA HBV Genotyping (Fujirebio Europe, Gent, Belgium) and (ii) direct nucleotide sequencing along with phylogenetic analysis.

Genotyping by line probe assay

A total of 835 extracted viral DNA samples were submitted to nested PCR amplification using specific biotinylated primers directed to the HBsAg genomic region supplied by the INNO-LiPA HBV Genotyping Kit. The PCR cycle conditions were based on the manufacturer’s protocol and amplicons were visualized in a 2 % agarose gel for certification of proper product length. PCR product denaturation, hybridization to genotype-specific probes immobilized on membrane strips and posterior processing of the strips in a streptavidin-based chromogenic reaction were performed using the automated workstation AutoBlot3000H (MedTec, North Carolina, USA). Reading and interpretation of strips were also automated using a scanner and LiRAS report software (Fujirebio Europe, Gent, Belgium). All participating laboratories processed the samples using this equipment and following the same protocol.

Genotyping by direct nucleotide sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

A total of 169 extracted HBV DNA samples were submitted to PCR amplification and nucleotide sequencing of a genomic region containing portions of both ORFs P and S with primers and thermal cycling profiles as described by Mallory et al. [58]. The generated PCR products of approximately 1 kb were purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, USA) and prepared for sequencing using the BigDye Terminator 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) along with internal sequencing primers as described by Mallory et al. [58]. Sequencing products were electrophoresed on an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

HBV genotyping was performed by phylogenetic analysis of the DNA sequences determined in this study compared with a multiple sequence alignment of HBV sequences representing all known genotypes available in GenBank. Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the maximum-likelihood method (bootstrap resampling test with 1000 replicates) in mega version 6.0 software [59] under the model of nucleotide substitution GTR+G+I, which was selected as the best-fit model by the jModeltest program [60].

Confirmation of INNO-LiPA results by direct sequencing and genotype-specific PCR assay

To confirm the reliability of genotyping results of the INNO-LiPA HBV Genotyping Kit, 10.2 % (85/835) of the samples were randomly selected for direct nucleotide sequencing. In addition to this randomly selected percentage of samples, those characterized by INNO-LiPA as genotypes B, C, E and H, rarely reported in Brazil, were also submitted to direct sequencing, upon availability of the specimen. Also, a semi-nested PCR assay using HBV genotype G-specific primers was performed as previously described [61] to confirm the high proportion of mixed infection with genotype G indicated by the INNO-LiPA assay results, especially mixed infection of genotypes D/G and F/G, an unusual profile of infection.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were used to describe the distribution of hepatitis B genotypes and categorical variables gender, age group and viral load range. Differences in genotype prevalence in each region and its comparison with previously reported data were also accessed by univariate analysis. Fisher’s exact test and Pearson's chi-squared test were used to test the significance level of associations, which was assessed at the 0.05 probability level. All analyses were conducted using the software Epi Info version 7.1 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA).

Funding information

This study was supported by funding from the ‘Ministério da Saúde, Fundo Nacional de Saúde, Departamento de DST/AIDS e Hepatites Virais’, approved in process number 25000.214350/2012–24.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the director of ‘Departamento de DST, AIDS e Hepatites Virais’, Dr Fabio Mesquita, and the directors and staff members of Laboratory of Public Health (Laboratório Central de Saúde Pública – LACEN) of the following Brazilian states: Acre, Alagoas, Amapá, Amazonas, Bahia, Ceará, Distrito Federal, Espírito Santo, Goiás, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais, Pará, Paraíba, Paraná, Pernambuco, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul, Roraima, Santa Catarina, Sergipe, Tocantins, Roraima, and Rondônia. The authors also thank the directors and staff members of ‘Laboratório Macro Regional de Saúde’ from Uberaba/MG, ‘Ambulatório de Hepatites Virais do FMT-HVD’ from Manaus/AM, ‘Fundação Ezequiel Dias/FUNED/MG’, and ‘Hospital Geral de Guarus’ from Campos dos Goytacazes/RJ.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) on 16 December 2013 (protocol number: 495.687) and conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Glossary

Supporting information.

Membership list of the Brazilian Hepatitis B Research Group

| No. | Name | Institution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ricardo Wagner de Almeida | Laboratório de Hepatites Virais, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil |

| 2 | Vanessa Duarte da Costa | |

| 3 | Bárbara Vieira do Lago | |

| 4 | Lia Laura Lewis Ximenes de Souza | |

| 5 | Natalia Picelli | Laboratório de Biologia Molecular do Hemocentro, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu, Unesp, Botucatu, SP, Brazil |

| 6 | Sarita Fiorelli Dias Barreto | |

| 7 | José Napoleão Monte da Cruz | Laboratório Central de Saúde Pública do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil |

| 8 | Eline Carvalho Pimentel de Oliveira | Laboratório Central de Saúde Pública da Bahia, Salvador, BA, Brazil |

| 9 | Leonardo de Assis Bertollo | |

| 10 | Gilza Bastos dos Santos Sanches | Laboratório Central de Saúde Pública do Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, MS, Brazil |

| 11 | Ana Olivia Pascoto Esposito | |

| 12 | Ana Flávia Nacif Pinto Coelho Pires | Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil |

| 13 | Bruna Lovizutto Protti Wohlke | Departamento de DST, AIDS e Hepatites Virais, Brasília, DF, Brazil |

| 14 | Miriam Franchini | |

| 15 | José Boullosa Alonso Neto | |

| 16 | Sonia Kaori Miyamoto | Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, PR, Brazil |

| 17 | Hellen Capellari Menezes | |

| 18 | Isabella Letícia Esteves Barros | |

| 19 | Marcilio Figueiredo Lemos | Instituto Adolfo Lutz, São Paulo, SP, Brazil |

| 20 | Wornei Silva Miranda Braga | Fundação de Medicina Tropical Doutor Heitor Vieira Dourado, Manaus, AM, Brazil |

| 21 | Marcia da Costa Castilho |

Supplementary Data

Footnotes

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus ; NGS, next-generation sequencing.

Five supplementary figures are available with the online Supplementary Material.

References

- 1.Gish RG, Given BD, Lai CL, Locarnini SA, Lau JY, et al. Chronic hepatitis B: virology, natural history, current management and a glimpse at future opportunities. Antiviral Res. 2015;121:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014;384:2053–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang ZH, Wu CC, Chen XW, Li X, Li J, et al. Genetic variation of hepatitis B virus and its significance for pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:126–144. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramvis A. Genotypes and genetic variability of hepatitis B virus. Intervirology. 2014;57:141–150. doi: 10.1159/000360947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norder H, Couroucé AM, Coursaget P, Echevarria JM, Lee SD, et al. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus strains derived worldwide: genotypes, subgenotypes, and HBsAg subtypes. Intervirology. 2004;47:289–309. doi: 10.1159/000080872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatematsu K, Tanaka Y, Kurbanov F, Sugauchi F, Mano S, et al. A genetic variant of hepatitis B virus divergent from known human and ape genotypes isolated from a Japanese patient and provisionally assigned to new genotype J. J Virol. 2009;83:10538–10547. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00462-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran TT, Trinh TN, Abe K. New complex recombinant genotype of hepatitis B virus identified in Vietnam. J Virol. 2008;82:5657–5663. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02556-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidd-Ljunggren K, Miyakawa Y, Kidd AH. Genetic variability in hepatitis B viruses. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1267–1280. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-6-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunbul M. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: global distribution and clinical importance. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5427–5434. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanwar S, Dusheiko G. Is there any value to hepatitis B virus genotype analysis? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s11894-011-0233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chávez JH, Campana SG, Haas P. [An overview of hepatitis B in Brazil and in the state of Santa Catarina] Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2003;14:91–96. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892003000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souto FJ. Distribution of hepatitis B infection in Brazil: the epidemiological situation at the beginning of the 21st century. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2016;49:11–23. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0176-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souto FJ. Hepatitis B and the human migratory movements in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2004;37:63–68. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822004000700010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araujo NM, Mello FC, Yoshida CF, Niel C, Gomes SA. High proportion of subgroup A' (genotype A) among Brazilian isolates of Hepatitis B virus. Arch Virol. 2004;149:1383–1395. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertolini DA, Gomes-Gouvêa MS, Guedes de Carvalho-Mello IM, Saraceni CP, Sitnik R, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes from European origin explains the high endemicity found in some areas from southern Brazil. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1295–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrilho FJ, Moraes CR, Pinho JR, Mello IM, Bertolini DA, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in haemodialysis centres from Santa Catarina state, Southern Brazil. Predictive risk factors for infection and molecular epidemiology. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mello FC, Souto FJ, Nabuco LC, Villela-Nogueira CA, Coelho HS, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes circulating in Brazil: molecular characterization of genotype F isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sitnik R, Pinho JR, Bertolini DA, Bernardini AP, da Silva LC, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and precore and core mutants in Brazilian patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2455–2460. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2455-2460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osiowy C, Giles E, Trubnikov M, Choudhri Y, Andonov A. Characterization of acute and chronic hepatitis B virus genotypes in Canada. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M. Geographical and genetic diversity of the human hepatitis B virus. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:14–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribeiro NR, Campos GS, Angelo AL, Braga EL, Santana N, et al. Distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes among patients with chronic infection. Liver Int. 2006;26:636–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chudy M, Schmidt M, Czudai V, Scheiblauer H, Nick S, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype G monoinfection and its transmission by blood components. Hepatology. 2006;44:99–107. doi: 10.1002/hep.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osiowy C, Gordon D, Borlang J, Giles E, Villeneuve JP. Hepatitis B virus genotype G epidemiology and co-infection with genotype A in Canada. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:3009–3015. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/005124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaaijer HL, Boot HJ, van Swieten P, Koppelman MH, Cuypers HT. HBsAg-negative mono-infection with hepatitis B virus genotype G. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:815–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crispim MA, Fraiji NA, Campello SC, Schriefer NA, Stefani MM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis Delta viruses circulating in the Western Amazon region, North Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Oliveira CM, Farias IP, Ferraz da Fonseca JC, Brasil LM, de Souza R, et al. Phylogeny and molecular genetic parameters of different stages of hepatitis B virus infection in patients from the Brazilian Amazon. Arch Virol. 2008;153:823–830. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dias AL, Oliveira CM, Castilho MC, Silva MS, Braga WS. Molecular characterization of the hepatitis B virus in autochthonous and endogenous populations in the Western Brazilian Amazon. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:9–12. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822012000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Souza KP, Luz JA, Teles SA, Carneiro MA, Oliveira LA, et al. Hepatitis B and C in the hemodialysis unit of Tocantins, Brazil: serological and molecular profiles. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:599–603. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762003000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobato C, Tavares-Neto J, Rios-Leite M, Trepo C, Vitvitski L, et al. Intrafamilial prevalence of hepatitis B virus in Western Brazilian Amazon region: epidemiologic and biomolecular study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:863–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eloy AM, Moreira RC, Lemos MF, Silva JL, Coêlho MR. Hepatitis B virus in the state of Alagoas, Brazil: genotypes characterization and mutations of the precore and basal core promoter regions. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17:704–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveira EH, Lima Verde RM, Pinheiro LM, Benchimol MG, Aragão AL, et al. HBV infection in HIV-infected subjects in the state of Piauí, Northeast Brazil. Arch Virol. 2014;159:1193–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1921-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barros LM, Gomes-Gouvêa MS, Kramvis A, Mendes-Corrêa MC, dos Santos A, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis B virus subgenotypes A1 and D4 in Maranhao state, Northeast Brazil. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;24:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Campos Albuquerque I, Sousa MT, Santos MD, Nunes JD, Moraes MJ, et al. Mutation in the S gene a determinant of the hepatitis B virus associated with concomitant HBsAg and anti-HBs in a population in Northeastern Brazil. J Med Virol. 2017;89:458–462. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yousif M, Kramvis A. Genotype D of hepatitis B virus and its subgenotypes: an update. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matos MA, Ferreira RC, Rodrigues FP, Marinho TA, Lopes CL, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection among injecting drug users in the Central-West Region of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:386–389. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762013000300019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveira MP, Matos MA, Silva ÁM, Lopes CL, Teles SA, et al. Prevalence, risk behaviors, and virological characteristics of hepatitis B virus infection in a group of men who have sex with men in Brazil: results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marinho TA, Lopes CL, Teles SA, Matos MA, Matos MA, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection among recyclable waste collectors in central Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:18–23. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0177-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freitas SZ, Soares CC, Tanaka TS, Lindenberg AS, Teles SA, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and genotypes of hepatitis B infection among HIV-infected patients in the state of MS, Central Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliveira MP, Lemes PS, Matos MA, del-Rios NH, Carneiro MA, et al. Overt and occult hepatitis B virus infection among treatment-naïve HIV-infected patients in Brazil. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1222–1229. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaspar AM, Yoshida CF. Geographic distribution of HBsAg subtypes in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1987;82:253–258. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761987000200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bottecchia M, Souto FJ, O KM, Amendola M, Brandão CE, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and resistance mutations in patients under long term lamivudine therapy: characterization of genotype G in Brazil. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clemente CM, Carrilho FJ, Pinho JR, Ono-Nita SK, da Silva LC, et al. A phylogenetic study of hepatitis B virus in chronically infected Brazilian patients of Western and Asian descent. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:568–576. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomes-Gouvêa MS, Ferreira AC, Teixeira R, Andrade JR, Ferreira AS, et al. HBV carrying drug-resistance mutations in chronically infected treatment-naive patients. Antivir Ther. 2015;20:387–395. doi: 10.3851/IMP2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haddad R, Martinelli AL, Uyemura SA, Yokosawa J. Hepatitis B virus genotyping among chronic hepatitis B patients with resistance to treatment with lamivudine in the city of Ribeirão Preto, State of São Paulo. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:224–228. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822010000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mello FC, Fernandes CA, Gomes SA. Antiviral therapy against chronic hepatitis B in Brazil: high rates of lamivudine resistance mutations and correlation with HBV genotypes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:317–325. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762012000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mendes-Correa MC, Pinho JR, Gomes-Gouvea MS, da Silva AC, Guastini CF, et al. Predictors of HBeAg status and hepatitis B viraemia in HIV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis B in the HAART era in Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tonetto PA, Gonçales NS, Fais VC, Vigani AG, Gonçales ES, et al. Hepatitis B virus: molecular genotypes and HBeAg serological status among HBV-infected patients in the southeast of Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saletto N. Sobre a composição étnica da população capixaba. Dimensões - Revista De História Da UFES. 2000;11:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becker CE, Kretzmann NA, Mattos AA, Veiga AB. Melting curve analysis for the screening of hepatitis B virus genotypes A, D and F in patients from a general hospital in southern Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50:219–225. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032013000200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gusatti CS, Costi C, Halon ML, Grandi T, Medeiros AF, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype D isolates circulating in Chapecó, Southern Brazil, originate from Italy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mello FM, Kuniyoshi AS, Lopes AF, Gomes-Gouvêa MS, Bertolini DA. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and mutations in the basal core promoter and pre-core/core in chronically infected patients in southern Brazil: a cross-sectional study of HBV genotypes and mutations in chronic carriers. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:701–708. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0158-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carvalho-Silva DR, Santos FR, Rocha J, Pena SD. The phylogeography of Brazilian Y-chromosome lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:281–286. doi: 10.1086/316931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang R, Cong X, Xu Z, Xu D, Huang W, et al. INNO-LiPA HBV genotyping is highly consistent with direct sequencing and sensitive in detecting B/C mixed genotype infection in Chinese chronic hepatitis B patients and asymptomatic HBV carriers. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1951–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hussain M, Chu CJ, Sablon E, Lok AS. Rapid and sensitive assays for determination of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes and detection of HBV precore and core promoter variants. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3699–3705. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3699-3705.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osiowy C, Giles E. Evaluation of the INNO-LiPA HBV genotyping assay for determination of hepatitis B virus genotype. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5473–5477. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5473-5477.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Acute exacerbations of chronic hepatitis B are rarely associated with superinfection of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2001;34:817–823. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toan NL, Song Leh, Kremsner PG, Duy DN, Binh VQ, et al. Impact of the hepatitis B virus genotype and genotype mixtures on the course of liver disease in Vietnam. Hepatology. 2006;43:1375–1384. doi: 10.1002/hep.21188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mallory MA, Page SR, Hillyard DR. Development and validation of a hepatitis B virus DNA sequencing assay for assessment of antiviral resistance, viral genotype and surface antigen mutation status. J Virol Methods. 2011;177:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Posada D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kato H, Orito E, Gish RG, Sugauchi F, Suzuki S, et al. Characteristics of hepatitis B virus isolates of genotype G and their phylogenetic differences from the other six genotypes (A through F) J Virol. 2002;76:6131–6137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6131-6137.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.