Abstract

Objective

To develop an evidence-based guideline to help clinicians make decisions about when and how to safely taper and stop antipsychotics; to focus on the highest level of evidence available and seek input from primary care professionals in the guideline development, review, and endorsement processes.

Methods

The overall team comprised 9 clinicians (1 family physician, 1 family physician specializing in long-term care, 1 geriatric psychiatrist, 2 geriatricians, 4 pharmacists) and a methodologist; members disclosed conflicts of interest. For guideline development, a systematic process was used, including the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. Evidence was generated from a Cochrane systematic review of antipsychotic deprescribing trials for the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, and a systematic review was conducted to assess the evidence behind the benefits of using antipsychotics for insomnia. A review of reviews of the harms of continued antipsychotic use was performed, as well as narrative syntheses of patient preferences and resource implications. This evidence and GRADE quality-of-evidence ratings were used to generate recommendations. The team refined guideline content and recommendation wording through consensus and synthesized clinical considerations to address common front-line clinician questions. The draft guideline was distributed to clinicians and stakeholders for review and revisions were made at each stage.

Recommendations

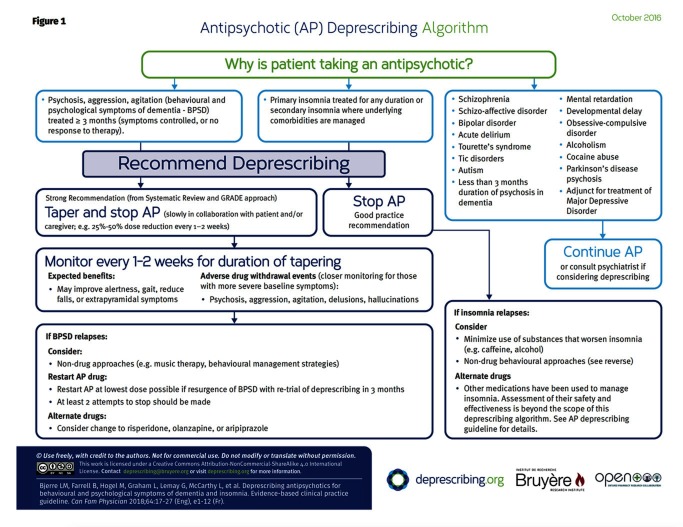

We recommend deprescribing antipsychotics for adults with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia treated for at least 3 months (symptoms stabilized or no response to an adequate trial) and for adults with primary insomnia treated for any duration or secondary insomnia in which underlying comorbidities are managed. A decision-support algorithm was developed to accompany the guideline.

Conclusion

Antipsychotics are associated with harms and can be safely tapered. Patients and caregivers might be more amenable to deprescribing if they understand the rationale (potential for harm), are involved in developing the tapering plan, and are offered behavioural advice or management. This guideline provides recommendations for making decisions about when and how to reduce the dose of or stop antipsychotics. Recommendations are meant to assist with, not dictate, decision making in conjunction with patients and families.

Deprescribing is the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or stopping of medication that might be causing harm or that might no longer be providing benefit.1 The goal of deprescribing is to reduce medication burden and harm while maintaining or improving quality of life. However, deprescribing can be difficult, especially when medications do not appear to be causing overt harm.2 In an effort to provide evidence-based recommendations and tools to aid clinicians in reducing or stopping medications that might no longer be needed or that might be causing harm, we initiated the Deprescribing Guidelines in the Elderly project (www.open-pharmacy-research.ca/research-projects/emerging-services/deprescribing-guidelines).

In a national modified Delphi consensus process, antipsychotics were selected as a high priority for deprescribing guideline development owing to their risk of harm and high prevalence of use.3

Antipsychotics are commonly used in the elderly, particularly in those residing in long-term care (LTC) facilities, to control certain behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) including delusions, hallucinations, aggression, and agitation when there is potential for harm to the patient or others.4 A 2014 meta-analysis demonstrated statistically significant improvements in symptoms of BPSD as measured using 5 different scales for patients taking atypical antipsychotics compared with placebo.5 However, antipsychotic treatment initiated for BPSD is often continued chronically, despite a lack of documented ongoing indications for many patients. Because behavioural features of dementia change over time as the disease progresses,6 it is important to reassess the continued need for treatment.

In addition to their use for treating BPSD, atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine are increasingly being used for their sedating properties in the treatment of insomnia. Prescriptions of quetiapine issued in Canada for sleep disturbances increased 10-fold in the 7-year period between 2005 and 2012.7

Antipsychotics have been associated with numerous side effects, the most severe of which are increased overall risk of death and increased risk of cerebrovascular adverse events.4 Atypical antipsychotics can cause weight gain and precipitate or worsen diabetes.8 While the absolute risk of some of these events is small, older people are often at higher risk of these outcomes. When antipsychotics are inappropriately prescribed or used for extended periods, they might contribute to polypharmacy, with its attendant risks of nonadherence, prescribing cascades, adverse reactions, medication errors, drug interactions, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations.9–12

Overuse of antipsychotics in the elderly has been a growing concern.13 A total of $75 million was spent on antipsychotic prescriptions dispensed to elderly patients in Canada in the second quarter of 2014, representing an increase in prescriptions of 32% in a 4-year span.13 In terms of volume, 22.4% of residents in Canadian LTC homes in 2014 were taking antipsychotics chronically.14

Our primary target audience includes Canadian primary care and LTC physicians, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, and specialists who care for patients taking antipsychotics.

Our target patient population includes elderly patients taking antipsychotics for the purpose of treating BPSD, for treating primary insomnia, or for treating secondary insomnia when the underlying comorbidities are managed. This guideline does not apply to those taking antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, acute delirium, Tourette syndrome or tic disorders, autism, mental retardation or developmental delay, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcoholism, cocaine abuse, or Parkinson disease psychosis; to those taking them as an adjunct for the treatment of depression; or if psychosis in patients with dementia has been treated for less than 3 months’ duration.

METHODS

We used a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise to develop the methods for the antipsychotic deprescribing guideline.15,16

The Guideline Development Team (GDT) comprised 9 clinicians (4 pharmacists [B.F., L.M., L.R.W., C.R.F.], 2 geriatricians [G.L., S.S.], 1 family physician [L.M.B.], 1 geriatric psychiatrist [A.W.], and 1 family physician specializing in LTC [L.G.]) and a Cochrane methodologist (V.W.). Expertise, role descriptions, and conflict of interest statements are available at CFPlus.* We selected a guideline chair (L.M.B.) based on expertise in pharmacoepidemiology and in primary care clinical medicine. A Canadian Library of Family Medicine librarian conducted searches in collaboration with 1 staff member (M.H.).

We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system for guideline development (Box 1).17–20 We generated 2 clinical management questions using the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) approach: What are the effects (harms and benefits) associated with deprescribing compared with continuation of antipsychotic medication for the treatment of BPSD in adults, and what are the benefits and harms associated with the treatment of insomnia with atypical antipsychotics?

Box 1. Notes on the GRADE framework for guideline development.

This guideline was developed in accordance with the methods proposed by the GRADE Working Group17 and was informed by a subset of data from an existing systematic review18 and by a new systematic review19,20:

We focused our review and recommendations on outcomes important to patients, such as harms or benefits resulting from deprescribing antipsychotic medication. Outcomes were proposed by the team lead and guideline coordinator and were reviewed and approved by the Guideline Development Team

Ratings in the evidence profile tables included high, moderate, low, or very low and depended on our confidence in the estimates of effect. Because only randomized controlled trials were used, they started with a high quality rating, but could be rated down by limitations in any of 4 domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, and imprecision. Other areas that were considered in formulating a final rating included harms, patient values and preferences, and resource use

The GRADE Working Group outlines appropriate wording for recommendations depending on the rating of strength and confidence in the evidence. A strong recommendation with implications for patients (phrased as “we recommend ...”) implies that all patients in the given situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not. A weak recommendation (phrased as “we suggest ...”) implies that most patients would wish to follow the recommendation, but some patients would not. Clinicians must help patients and caregivers make treatment decisions consistent with patients’ values and preferences. Implications for clinicians are similar such that a strong recommendation implies all or most patients should receive the intervention. A weak recommendation should prompt a clinician to recognize that different choices will be appropriate for individual patients

GRADE—Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

The first question was addressed using the results of the 2013 Cochrane review “Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia.”18 We communicated with the Managing Editor for the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, who updated the search for this review in March of 2015, and concluded that no additional studies that met their inclusion criteria had been published since the 2013 review. Patient-important outcomes included the ability to successfully withdraw medication, a change in BPSD, the presence or absence of withdrawal symptoms, a change in the adverse effects of antipsychotics, a change in quality of life, and mortality. The results from individual studies for the outcomes of interest could not be pooled; thus, we produced a narrative summary of findings, which can be found at CFPlus.*

As there were no studies examining the deprescribing of antipsychotics used for the treatment of insomnia, we decided to focus on finding evidence for the effectiveness of such treatment. To answer our second PICO question, we conducted a systematic review to study the efficacy of antipsychotics for insomnia, focusing on patient-important outcomes such as total sleep time, latency to sleep, and sleep satisfaction.19,20

The GDT chair drafted recommendations based on the summaries of evidence, taking into account literature on patient preferences about antipsychotic use, a review of reviews of harms of continuing antipsychotic use, and resource implications (in terms of antipsychotic cost and costs potentially associated with stopping antipsychotics). Members reviewed the draft recommendations and discussed them in person and via teleconference. Voting on the recommendations was subsequently conducted anonymously by e-mail. Unanimous agreement was sought; 80% agreement (ie, 8 of the 10 GDT members) was considered the cutoff for consensus. All 10 members of the GDT agreed with the recommendations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The recommendations are outlined in Box 2. The algorithm developed for this guideline is provided in Figure 1. The GRADE evidence tables used to evaluate the evidence for each patient-important outcome can be found at CFPlus.* The rationale for the recommendations is outlined in Table 1.18 The recommendations apply to adults who have been prescribed antipsychotics for insomnia or for BPSD, provided the symptoms of the latter are controlled or the patient is unresponsive to a reasonable trial of therapy. The evidence base for deprescribing relates mainly to patients with BPSD but can be extrapolated to those with insomnia or when short-term use is generally adequate (eg, transient delirium or psychosis unrelated to BPSD). The recommendations do not apply to those who have been prescribed antipsychotics for the treatment of disorders such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, acute delirium, Tourette syndrome or tic disorders, autism, mental retardation or developmental delay, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcoholism, cocaine abuse, or Parkinson disease psychosis; or as an adjunct in the treatment of depression; or for the treatment of delusions and hallucinations in patients with dementia.

Box 2. Recommendations for deprescribing antipsychotics.

For adults with BPSD treated for at least 3 mo (symptoms stabilized or no response to adequate trial), we recommend the following:

Taper and stop antipsychotics slowly in collaboration with the patient and caregivers: eg, 25%–50% dose reduction every 1–2 wk (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence)

For adults with primary insomnia treated for any duration or secondary insomnia in which underlying comorbidities are managed, we recommend the following:

Stop antipsychotics; tapering is not needed (good practice recommendation)

BPSD—behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Figure 1.

Table 1.

Evidence to recommendations table for deprescribing APs: Does deprescribing (dose reduction or frank discontinuation) APs compared with continuous AP use result in benefits or harms for adults > 18 y (excluding those prescribed APs for treatment of psychosis) in primary care and LTC settings?

| DECISION DOMAIN | SUMMARY OF REASON FOR DECISION | SUBDOMAINS INFLUENCING DECISION |

|---|---|---|

| QoE: Is there high- or moderate-quality evidence? Yes ☑ No □ (See references 1–10 in the evidence reviews at CFPlus*) | The QoE for the success of deprescribing is high

The QoE for effectiveness of atypical APs for insomnia is very low

|

The baseline symptom level might have an influence on the success of deprescribing APs. Patients with more severe baseline scores were more likely to experience relapses (defined as a 30% increase in the NPI score) in 2 studies. Withdrawal in patients with severe behavioural baseline scores might not be successful or should not be attempted |

| Balance of benefits and harms: Is there certainty that the benefits outweigh the harms? Yes ☑ No □ (See references 1–9 in the evidence reviews at CFPlus*) |

Overall, benefits of AP deprescribing appear to outweigh harms

Effectiveness of atypical APs for insomnia

|

Is the baseline risk for benefit similar across subgroups? Yes ☑ No □ Should there be separate recommendations for subgroups based on risk levels? Yes □ No ☑ Is the baseline risk for harm similar across subgroups? Yes □ No ☑

Should there be separate recommendations for subgroups based on harms? Yes ☑ No□

|

| Values and preferences: Is there confidence in the estimate of relative importance of outcomes and patient preferences? Yes ☑ No □ |

Reasons for prescribing APs include aggressive behaviour (physical and verbal), easier management of patients during daily care, as a sleep aid, or to help caregivers cope. Other viable options, such as nonpharmacologic alternatives, are less widely used owing to limited access, being highly resource dependent, and requiring additional staff training. APs can have a small effect in decreasing caregiver burden. Thus, there might be resistance from home-care staff when decreasing AP use or pressure from nursing home staff to prescribe APs. Inadequate staffing, additional workload, and increased demands are barriers to decreasing APs. Caregivers find the use of APs for controlling behaviour harmful. In addition, caregivers observe better patient QoL when APs are not used. Families would like more information on the side effects of APs |

Perspective taken: the perspectives of the patient and caregivers are central to the decision to deprescribe APs, but so is the availability of professional health care support to monitor and accompany the process Source of values and preferences: literature review, pilot study of guidelines in both LTC and outpatient settings Source of variability, if any: variability difficult to estimate Method for determining values satisfactory for this recommendation? Yes ☑ No□ All critical outcomes measured? Yes ☑ No □

|

| Resource implications: Are the resources worth the expected net benefit? Yes ☑ No □ |

As there is little evidence about cost implications of deprescribing APs, and none about cost-effectiveness, it is difficult to precisely estimate this trade-off. It is likely that in some cases deprescribing APs might lead to increased caregiver resource requirements; on the other hand, patients will no longer be exposed to numerous potential side effects of APs (increased risk of falls, stroke, death, somnolence, confusion, dizziness, EPS, metabolic disturbances, weight gain, anticholinergic side effects, tardive dyskinesia, orthostatic hypotension, cardiac conduction disturbances, sedation, cognitive slowing); medication costs will also decrease |

Feasibility: Is this intervention generally available? Yes ☑ No □ Opportunity cost: Is this intervention and its effects worth withdrawing or not allocating resources from other interventions? Yes ☑ No □ Is there a lot of variability in resource requirements across settings? Yes ☑ No □

|

| Strength of main recommendation: strong | The strong recommendation is based on the lack of evidence of substantial harms of deprescribing APs for BPSD, the evidence for benefits of avoiding unnecessary exposure to APs, the societal costs of inappropriate AP use, and the feasibility of this intervention in primary care and LTC; for insomnia, there is a lack of evidence for efficacy of APs and there is potential for harm | |

| Remarks and values and preference statement | These recommendations place a high value on the minimal clinical risk of deprescribing, reducing the inappropriate use of APs and their side effects, and the associated resource use given the high cost, both monetary and nonmonetary, associated with long-term AP use. They place some value on the potential for harms from attempted deprescribing and on potentially increased caregiver resource use as a result of deprescribing APs | |

AP‑antipsychotic, BPSD‑behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, EPS‑extrapyramidal symptoms, LTC‑long-term care, MD‑mean difference, NPI‑Neuropsychiatric Inventory, NPS‑neuropsychiatric symptoms, QoE‑quality of evidence, QoL‑quality of life, RCT‑randomized controlled trial.

For patients stabilized for a minimum of 3 months on antipsychotic treatment for BPSD, gradual withdrawal of antipsychotics does not lead to worsening symptoms compared with those who continue taking antipsychotics. No consistent changes in cognition, mortality, or quality of life were observed, although 1 study found a significant decrease in mortality among those who discontinued antipsychotic treatment21; a second small study found worsening of sleep efficiency in those who had had antipsychotics withdrawn.22 Table 1 outlines the evidence to recommendations considerations across all decision domains for deprescribing of antipsychotics in BPSD (quality of evidence, balance of benefits and harms, patient values and preferences, and resource implications).18 With regard to treatment of insomnia, only 1 small study (13 patients) was found; no results were statistically significant for benefit.23

Based on the lack of evidence of the harm of deprescribing and the evidence for the benefit of reducing inappropriate antipsychotic use in terms of avoidance of the drug-related harms, the high societal cost of inappropriate antipsychotic use, the potential net cost benefit of switching to behavioural therapy, and the feasibility of an antipsychotic deprescribing intervention, we rated the recommendation to reduce or stop antipsychotic use for the treatment of BPSD as strong. Based on the lack of evidence for the efficacy of antipsychotics for treating insomnia, and the potential for harm and high cost, we rated the recommendation to eliminate antipsychotic use for the treatment of insomnia as strong.

Considerations of harms include the potential of well-known side effects (drowsiness, headache, extrapyramidal symptoms, weight gain, etc) and a heightened awareness of more serious adverse events, including a 1.5- to 2.0-fold increased risk of death and a 2.0-fold increased risk of cerebrovascular events.24 While the absolute risks of these serious adverse events are low and have not been confirmed in recent studies, they are serious enough to have prompted Health Canada to issue a warning. The ranges of frequency ratios of harms are available at CFPlus.*

With regard to values and preferences, some family members and front-line caregivers believe that the benefits of using antipsychotics for BPSD, including reducing caregiver burden, outweigh the risks of side effects despite an understanding of and concern about associated negative outcomes. However, others think those taking antipsychotics have a lower quality of life, and some will remove individuals from residential settings to reduce the risk that they will be prescribed antipsychotics. Providers, caregivers, and family members are aware of the difficulties in reducing antipsychotic use, including inadequate staffing, education, and resources for nonpharmacologic approaches. As treatment decisions are usually influenced by family expectations, attempts to withdraw antipsychotics should include their input. Evidence reviews and related references are available at CFPlus.*

In Canada, antipsychotic costs for seniors during the second quarter of 2014 reached $75 million.13 The rate of prescribing is 14 times higher in LTC facilities than in the community setting.13 Cost-effectiveness studies examining treatment options for BPSD show that behavioural interventions, such as cognitive stimulation therapy, are projected to reduce costs, compared with antipsychotic use, from avoided falls and strokes and when quality-of-life improvements were considered.25 Antipsychotic use for treating BPSD has been shown to have a small but statistically significant effect on reducing caregiver burden, similar to the effects of support groups and psycho-educational interventions; however, the cost implications vary.26,27 Evidence reviews and related references can be found at CFPlus.*

Clinical considerations

Combined with clinical judgment and an individualized approach to care, this guideline is intended to support clinicians and patients in successfully deprescribing antipsychotics, ultimately striving for better patient care.

The following questions were articulated by the GDT as being important to consider when making decisions about the steps for deprescribing antipsychotics.

Is there an indication and are there risk factors that warrant continued use?

An important first step is to clarify when the antipsychotic was started and for what reason. This might require a chart review and discussion with the patient, caregivers, other prescribers (often other specialists), or pharmacist. If patients are using antipsychotics for insomnia, deprescribing is compelling, as there are no data to support antipsychotic use for this specific indication. Examples of patients in whom antipsychotics should be continued include those meeting exclusion criteria (eg, taking antipsychotics for psychosis), patients for whom repeated attempts have been made to deprescribe without success, and, in some cases, patients who recently started taking antipsychotics for BPSD and in whom it is too early to assess benefits and harms.

Guidelines such as those from the Fourth Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia suggest that risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole should be considered for patients with severe agitation, aggression, and psychosis associated with dementia when there is risk of harm to the patient or others.28 However, research has demonstrated that antipsychotic medications have little to no effect on many BPSDs, such as wandering, hiding, hoarding, repetitive activities, vocally disruptive behaviour, and inappropriate dressing, and thus their use for such indications is inappropriate.29

How should tapering be approached?

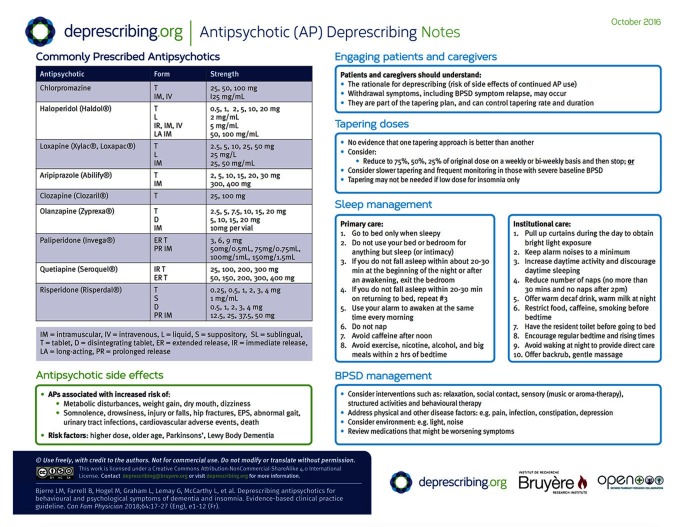

Our literature review of antipsychotic deprescribing in BPSD did not identify trials that compared tapering approaches to minimize symptom recurrence. Of the studies included in the Cochrane review18 evaluating withdrawal of antipsychotics for BPSD, 7 studies used a taper strategy involving a 50% reduction in dosage per week over a period varying from 1 to 3 weeks, while 3 studies employed abrupt discontinuation. Clinicians at the LTC sites where this deprescribing guideline was piloted were not comfortable with what was perceived as rapid tapering in the Cochrane review; they preferred slower tapering, as reflected in Figure 1. However, they were comfortable with abrupt cessation when low-dose antipsychotics had been prescribed for insomnia. Tapering strategies are outlined in Box 3.30

Box 3. Suggested tapering strategies.

For those prescribed antipsychotics for the treatment of BPSD, we recommend considering the following:

Reduce to 75%, 50%, and 25% of the original dose on a biweekly basis before stopping

Alternatively, reduce the previous dose by approximately 50% every week down to 25% of the initial dose, then stop

In addition we recommend the following:

For patients with severe baseline BPSD symptoms or long-standing use of antipsychotics, we recommend slower tapering, close monitoring for withdrawal symptoms, and establishing a clear intervention plan emphasizing the use of nonpharmacologic approaches first, in the event of increased severity or recurrence of neuropsychiatric symptoms

Furthermore, tapering might need to be individualized depending on the starting dose, available dosage forms, and how tapering is tolerated

For those prescribed antipsychotics for the treatment of insomnia, we recommend the following:

If the patient has been taking an antipsychotic for a short period of time (eg, < 6 wk), stop antipsychotic use immediately. If the patient has been taking the antipsychotic for a longer period of time, consider tapering the dose first before stopping. If there are concerns on the part of either the patient or the prescriber about possible side effects of immediate discontinuation, tapering can also be considered

All patients should be counseled about nonpharmacologic approaches to sleep (so-called sleep hygiene)30

BPSD—behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

In all cases, regardless of the severity of BPSD or the use for insomnia, patient and caregiver involvement in the decision to deprescribe antipsychotics is essential. Good communication should include the rationale (eg, risk of side effects) and consideration of values and preferences, and should ensure understanding and agreement with the proposed changes (“buy-in”), as well as involvement in making the deprescribing and monitoring plans.31

What monitoring needs to be done and how often?

It is important to clarify with the patient, family, and health care staff what specific symptoms are being treated, what the desired response to treatment is, and the need to monitor the actual response following antipsychotic initiation and, likewise, discontinuation. This might require a retrospective chart review with the aim of documenting changes in the frequency or severity of target symptoms. It might be of value to use an objective measure such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) subscales or the behavioural subscales of the Resident Assessment Instrument–Minimum Data Set tool to quantify the frequency and severity of the symptoms at baseline and follow these parameters through time. Response can be defined as a decrease of 50% in the 3 target symptoms (psychosis, agitation, aggression).32 Physicians and caregivers should also monitor for expected benefits of deprescribing (such as reduced falls and improved cognition, alertness, function, extrapyramidal symptoms, and gait). Close monitoring (eg, every 1 to 2 weeks) is essential during the tapering process, and the use of objective measures can be helpful in identifying any behavioural recurrence or withdrawal symptoms, as well as the success of deprescribing.

Predictors of successful discontinuation of therapy include lower baseline severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI score < 15)33,34 and lower dosage of antipsychotic to achieve symptom control.22,35 Those receiving a higher dosage and those with higher NPI scores or higher global severity (as NPI or other tools are not commonly used) might require closer monitoring. Monitoring tools such as the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, which is brief and easy to apply, might be more amenable to use for patients in LTC settings, where health care professionals are present.36,37 In the outpatient setting, family and caregiver involvement is key to monitoring behavioural recurrence, with close medical follow-up.

How should symptoms be managed?

Nonpharmacologic approaches for insomnia (minimizing caffeine or alcohol that can worsen insomnia, or behavioural approaches) or other pharmacologic alternatives as suggested in contemporary sleep guidelines30,38,39 should be considered, keeping in mind that such guidelines are not specific to the geriatric population. Some of the recommended alternatives might not be appropriate for the elderly (eg, benzodiazepines, amitriptyline, zopiclone).40

Nonpharmacologic approaches should be considered before pharmacologic approaches for management of BPSD when the situation is not urgent or when symptoms are not severe.29 These approaches could include social contact interventions, sensory or relaxation interventions (eg, music therapy, aromatherapy), structured activities, or behavioural therapy.29

In patients whose BPSD recurs with discontinuation, addressing pain might be of value, as it is a common underlying cause of agitation in dementia; a recent randomized controlled trial in 352 patients reported a 17% improvement in agitation after stepped treatment with analgesics, similar to the benefit seen with antipsychotics.41 Further search for triggers and exacerbating factors including other diseases (eg, common viral illnesses, other infections), environmental causes (eg, new routine, relocation), physical problems (eg, constipation), other medications, and depression might also be of value.42 Such treatment is not a direct alternative to antipsychotics, but plays an important part in managing and preventing agitation and might reduce the need to restart antipsychotics. Realistically, some patients will not be successful with discontinuation; restarting an antipsychotic43 (eg, risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole)44 at the lowest dose possible can be done with retrial of discontinuation after 3 months.45

Clinical and stakeholder review

External clinical review of the guideline was conducted by a pharmacist, a geriatrician, a family physician, and a nurse using the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation) Global Rating Scale tool.46 Relevant stakeholder organizations (eg, family practice, pharmacy, psychology, LTC) were invited to similarly review and endorse the guidelines (Box 4). Modifications were made to the original guideline draft to address reviewer comments.

Box 4. Guideline endorsements.

This evidence-based clinical practice guideline for antipsychotics has been endorsed by the following groups:

College of Family Physicians of Canada

Canadian Pharmacists Association

Canadian Society of Consultant Pharmacists

How this deprescribing guideline relates to other clinical practice guidelines for antipsychotics

Existing clinical practice guidelines,43,47 including Canadian guidelines,29,44 as well as best-practice recommendations for older adults,40,48 consistently support the use of antipsychotics for BPSD only when patients are at risk of harming themselves or pose a considerable threat to others. In a 2012 systematic appraisal of guidelines for BPSD, Azermai et al reported that only 2 of the 15 evaluated guidelines addressed discontinuation of antipsychotics.49 Both recommended deprescribing after 3 to 6 months of behavioural stability.49 More recent guidelines44,47 or evidence-based updates to guidelines acknowledge that antipsychotics prescribed for the treatment of BPSD can be safely withdrawn in many patients, and discontinuation should be attempted when symptoms are stabilized.43 There is no information in current guidelines to assist physicians with deprescribing approaches (eg, tapering or abrupt cessation).

An antipsychotic deprescribing guideline supplements current treatment guidelines in offering clinicians recommendations and clinical considerations to support the deprescribing of antipsychotics after BPSD has been stabilized or following an appropriate trial without response to treatment.

Evidence-based and best-practice guidelines for treatment of insomnia recommend against using antipsychotics in all age groups, except when patients have comorbid insomnia related to conditions that are amenable to treatment with antipsychotics (eg, severe anxiety or bipolar disorder).38,39,48,50

Gaps in knowledge

Despite the widespread use of antipsychotics, numerous gaps in knowledge exist that could alter the strength of the recommendations in this guideline.

What are patients’ values and preferences regarding the use or deprescribing of antipsychotics for treating BPSD? Although there might be difficulties in obtaining reliable and usable data from this population, it is nonetheless a valuable perspective that should be included in weighing the benefits against the harms of using antipsychotics for BPSD. Such information would inform prescriber-patient-family discussions about BPSD treatment and deprescribing.

What are the indirect costs or cost savings associated with deprescribing antipsychotics for the treatment of BPSD? These indirect costs could result from changed caregiver requirements—either increased, if symptoms worsen, or decreased, if patients become more independent with activities of daily living—when a patient’s antipsychotic medication is reduced or discontinued.

In the case of the use of antipsychotics for treating insomnia, several additional pieces of evidence would have proven beneficial in weighing the benefits and harms of deprescribing. Are antipsychotics effective for treating insomnia? Only 1 study involving 13 participants was identified in the literature.23 Given that it showed modest but not statistically significant improvements in all 3 sleep outcomes, additional studies could strengthen the evidence for or against using antipsychotics for this purpose. What are the effects of deprescribing antipsychotics prescribed for the treatment of insomnia? What is the adverse effect profile of antipsychotics prescribed for the treatment of insomnia? Antipsychotics are generally taken at a lower dose for the treatment of insomnia than for other indications; however, the harms literature generally reports on antipsychotics used at higher doses. The adverse effect profile might not be the same in the case of insomnia.

What is the most effective strategy for tapering or stopping antipsychotics? Direct comparison of different deprescribing approaches would be helpful to determine if there is a best approach. This evidence would improve prescriber confidence in taking a patient off an antipsychotic.

Last, and falling outside the recommendations of this guideline, family physicians often see patients prescribed antipsychotics by psychiatrists for reasons other than BPSD or insomnia. Trials examining the outcomes of deprescribing antipsychotics for those with other conditions would prove beneficial to health care professionals weighing the harms and benefits of deprescribing in patients who might also be at higher risk of the adverse effects of continued antipsychotic treatment.

Next steps

The deprescribing team will endeavour to provide routine guideline updates as new evidence emerges that could change the recommendations. Prospective evaluation of the effects of the adoption of this and other deprescribing guidelines will be part of the research strategy in the future.

Conclusion

Overuse of medication is acknowledged to be a key contributor to polypharmacy, with attendant negative effects on health. Antipsychotics are increasingly used for indications for which they are not licensed or for which they have not been studied, such as BPSD and insomnia, yet their potential for harm with long-term use is well established. A systematic review identified that antipsychotics can be safely deprescribed in many patients with BPSD.18 Our systematic review of antipsychotic use in insomnia19,20 did not identify any studies of discontinuation that could inform our present guideline; however, we were also unable to find evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for treating insomnia in the first place, suggesting that patients receiving antipsychotics for insomnia should have them stopped. When deprescribing antipsychotics, patient, family member, and caregiver involvement is crucial. The evidence, tapering strategies, and associated algorithm presented in this current guideline are intended to support this process.

This evidence-based guideline is one of a series of guidelines aimed at helping clinicians make decisions about when and how to safely stop medications. Implementation of such guidelines will encourage clinicians to carefully evaluate the ongoing use of medications and potentially reduce the negative effects of polypharmacy in the future.

Acknowledgments

For their clinical review of the guideline and invaluable feedback, we thank Allison Bell, a pharmacist with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority in Manitoba; Dr David Strang, a geriatrician with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority; Dr John Crosby, a family physician practising in Cambridge, Ont; and Linda Hunter, former Chief Nursing Officer at Perley and Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre in Ottawa, Ont.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

▸ Antipsychotics are frequently used to control behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and for the treatment of insomnia.

▸ Antipsychotics have the potential for considerable harm, including an increased overall risk of death, cerebrovascular adverse events, extrapyramidal symptoms, gait disturbances and falls, somnolence, edema, urinary tract infections, weight gain, and diabetes; the risk of harm is higher with prolonged use and in the elderly.

▸ A systematic review of antipsychotic deprescribing (dose reduction or discontinuation) in patients taking them to control BPSD failed to demonstrate negative outcomes resulting from deprescribing.

▸ The evidence in support of the effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for insomnia is poor and of low quality.

▸ This guideline recommends deprescribing antipsychotics in elderly patients taking them for insomnia and in adults who have had an adequate trial for BPSD (ie, behaviour stabilized for 3 months or unresponsive to treatment).

Footnotes

Descriptions of contributors’ expertise, roles, and conflicts of interest; the narrative summary of findings and related references; the GRADE evidence tables; the ranges of frequency ratios of harms; and an easy-to-print version of the algorithm are available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Contributors

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the guideline; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approving the final version.

Competing interests

Dr Farrell received research funding to develop this guideline; received financial payments from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Commonwealth Fund for a deprescribing guidelines summary; and from the Ontario Long Term Care Physicians Association, the Ontario Pharmacists Association, and the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists for speaking engagements. Dr Bjerre received a financial payment from the Ontario Long Term Care Physicians association for a speaking engagement. None of the other authors has any competing interests to declare.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de janvier 2018 à la page e1.

References

- 1.Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66(3):201–2. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v66i3.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthierens S, Tansens A, Petrovic M, Christiaens T. Qualitative insights into general practitioners views on polypharmacy. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrell B, Tsang C, Raman-Wilms L, Irving H, Conklin J, Pottie K. What are priorities for deprescribing for elderly patients? Capturing the voice of practitioners: a modified Delphi process. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):191–210. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000200589.01396.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma H, Huang Y, Cong Z, Wang Y, Jiang W, Gao S, et al. The efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(3):915–37. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jost BC, Grossberg GT. The evolution of psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a natural history study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(9):1078–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pringsheim T, Gardner DM. Dispensed prescriptions for quetiapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Canada from 2005 to 2012: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E225–32. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson SC, Le L, Zakharyan A, Stockl KM, Harada AS, Borson S, et al. New-onset treatment-dependent diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia associated with atypical antipsychotic use in older adults without schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(3):474–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03842.x. Epub 2012 Jan 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes BD, Klein-Schwartz W, Barrueto F., Jr Polypharmacy and the geriatric patient. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23(2):371–90. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang AR, Mallet L, Rochefort CM, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Tamblyn R. Medication-related falls in the elderly: causative factors and preventive strategies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(5):359–76. doi: 10.2165/11599460-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):173–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ontario Drug Policy Research Network . Antipsychotic use in the elderly. Toronto, ON: Ontario Drug Policy Research Network; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Use of antipsychotics among seniors living in long-term care facilities, 2014. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell B, Pottie K, Rojas-Fernandez C, Bjerre LM, Thompson W, Welch V. Methodology for developing deprescribing guidelines: using evidence and GRADE to guide recommendations for deprescribing. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schunemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, Falavigna M, Santesso N, Mustafa R, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):E123–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. Epub 2010 Dec 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, Vander SR, De Sutter AI, van Driel ML, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD007726. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007726.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson W, Quay T, Tang J, Bjerre LM, Farrell B. Atypical antipsychotics for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO. 2015. CRD42015017748. Available from: www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42015017748. Accessed 2017 Nov 20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Thompson W, Quay T, Rojas-Fernandez C, Farrell B, Bjerre LM. Atypical antipsychotics for insomnia: a systematic review. Sleep Med. 2016;22:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.04.003. Epub 2016 May 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballard C, Hanney ML, Theodoulou M, Douglas S, McShane R, Kossakowski K, et al. The dementia antipsychotic withdrawal trial (DART-AD): long-term follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):151–7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70295-3. Epub 2009 Jan 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruths S, Straand J, Nygaard HA, Aarsland D. Stopping antipsychotic drug therapy in demented nursing home patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled study—the Bergen District Nursing Home Study (BEDNURS) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):889–95. doi: 10.1002/gps.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tassniyom K, Paholpak S, Tassniyom S, Kiewyoo J. Quetiapine for primary insomnia: a double blind, randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(6):729–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement . An economic evaluation of alternatives to antipsychotic drugs for individuals living with dementia. Coventry, UK: Coventry House; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Lyketsos CG, Kaczynski R, Sultzer DL, Schneider LS. Effect of second-generation antipsychotics on caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):121–8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore A, Patterson C, Lee L, Vedel I, Bergman H. Fourth Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia. Recommendations for family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:433–8. (Eng), e244–50 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health . National guidelines for seniors’ mental health: the assessment and treatment of mental health issues in long term care homes (focus on mood and behaviour symptoms) Toronto, ON: Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cote K. Normal sleep and sleep hygiene. Canadian Sleep Society; 2004. Available from: http://giic.rgps.on.ca/files/normal_sleep.pdf. Accessed 2017 Nov 20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793–807. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devanand DP, Pelton GH, Cunqueiro K, Sackeim HA, Marder K. A 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot discontinuation trial following response to haloperidol treatment of psychosis and agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(9):937–43. doi: 10.1002/gps.2630. Epub 2010 Dec 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballard CG, Thomas A, Fossey J, Lee L, Jacoby R, Lana MM, et al. A 3-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, neuroleptic discontinuation study in 100 people with dementia: the Neuropsychiatric Inventory median cutoff is a predictor of clinical outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):114–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballard C, Lana MM, Theodoulou M, Douglas S, McShane R, Jacoby R, et al. A randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled trial in dementia patients continuing or stopping neuroleptics (the DART-AD trial) PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Reekum R, Clarke D, Conn D, Herrmann N, Eryavec G, Cohen T, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the discontinuation of long-term antipsychotics in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(2):197–210. doi: 10.1017/s1041610202008396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheehan B. Assessment scales in dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012;5(6):349–58. doi: 10.1177/1756285612455733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen-Mansfield J. Instruction manual for the Cohen-Mansfield Agistation Inventory (CMAI) Rockville, MD: The Research Institute of the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(5):487–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ, Alford C, Argyropoulos SV, Baldwin DS, Bateson AN, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(11):1577–601. doi: 10.1177/0269881110379307. Epub 2010 Sep 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–46. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. Epub 2015 Oct 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corbett A, Husebo B, Malcangio M, Staniland A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Aarsland D, et al. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(5):264–74. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.53. Erratum in: Nat Rev Neurol 2013;9(7):358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hort J, O’Brien JT, Gainotti G, Pirttila T, Popescu BO, Rektorova I, et al. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(10):1236–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rabins RV, Rovner BW, Rummans T, Schneider LS, Tariot PN. Guideline watch (October 2014): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: The American Psychiatric Association; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, Gordon M, Herrmann N, Rockwood K, et al. Recommendations of the 4th Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia (CCCDTD4) Can Geriatr J. 2012;15(4):120–6. doi: 10.5770/cgj.15.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand . Antipsychotics in dementia: best practice guide. Dunedin, NZ: Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. The Global Rating Scale complements the AGREE II in advancing the quality of practice guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(5):526–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.10.008. Epub 2011 Dec 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Manchester, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Psychiatric Association . Choosing Wisely: five things physicians and patients should question. Philadelphia, PA: Choosing Wisely; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Azermai M, Petrovic M, Elseviers MM, Bourgeois J, Van Bortel LM, Vander Stichele RH. Systematic appraisal of dementia guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.07.002. Epub 2011 Aug 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry, Canadian Psychiatric Association . Thirteen things physicians and patients should question. Toronto, ON: Choosing Wisely Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]