Plantar fasciitis (PF) is the most commonly reported cause of inferior heel pain, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 3.6% to 7% in the general population.1,2 In runners, it is one of the most common injuries, accounting for up to 8% of all running-related injuries.3 The term fasciitis, commonly used in the literature, is likely a misnomer, as studies have introduced evidence showcasing a degenerative disease process without evidence for inflammation, suggesting that fasciosis or fasciopathy might be more appropriate terms.4

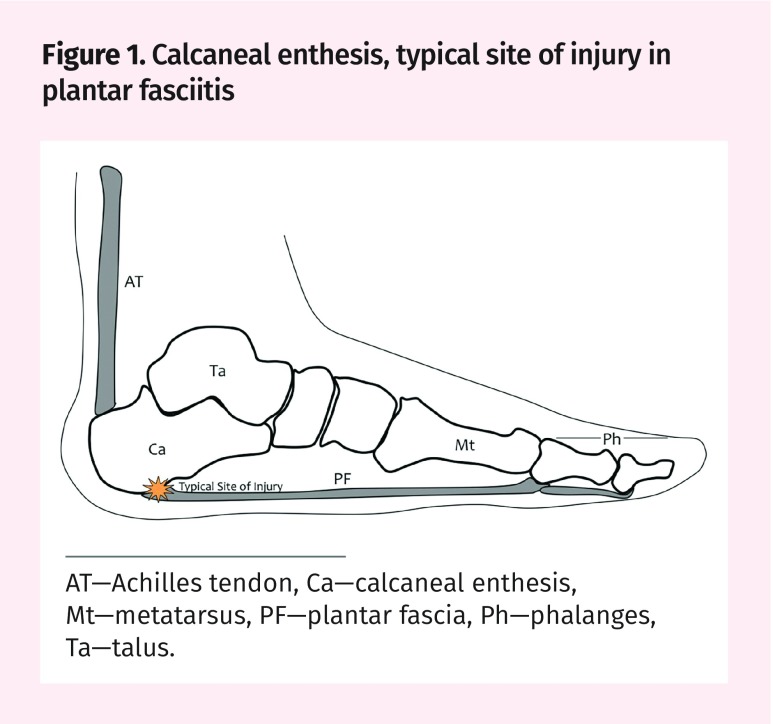

The plantar fascia is a thick sheath of type 1 collagen that supports the arch of the foot. It originates from the calcaneal tuberosity and inserts into the heads of the metatarsal bones.5 Its main function is to support the arch of the foot and act as a tension bridge, providing support while stationary as well as shock absorption during movement.6 In both active and sedentary individuals, PF is thought to be caused by prolonged standing or running, resulting in biomechanical overuse leading to microtears at the calcaneal enthesis (Figure 1).7

Figure 1.

Calcaneal enthesis, typical site of injury in plantar fasciitis

AT—Achilles tendon, Ca—calcaneal enthesis, Mt—metatarsus, PF—plantar fascia, Ph—phalanges, Ta—talus.

Available treatment options for PF include local steroid injections, orthotics, night splinting, and stretching. While symptoms typically improve within a year of onset regardless of treatment, approximately 40% of patients continue to have symptoms after 2 years.8 This suggests the need for novel therapies in order to better treat the considerable pain and disability associated with PF. One such example is high-load strength training (HLST). The purpose of HLST is to stress a tendon with a high tensile load in order to stimulate collagen production and, ultimately, expedite recovery.9 High-load strength training has shown promise in treating other degenerative tendon disorders such as Achilles and patellar tendinopathy, and more recently PF.9 In patients with PF, loading of the Achilles tendon in conjunction with dorsal flexion of the metatarsophalangeal joints (windlass mechanism) can be used to synergistically cause high-load tensile forces across the plantar fascia (Figure 2).9

Figure 2.

Loading of the Achilles tendon in conjunction with dorsal flexion of the metatarsophalangeal joints (windlass mechanism) can be used to synergistically cause high-load tensile forces across the plantar fascia

AT—Achilles tendon, Ca—calcaneal enthesis, Mt—metatarsus, PF—plantar fascia, Ph—phalanges, Ta—talus.

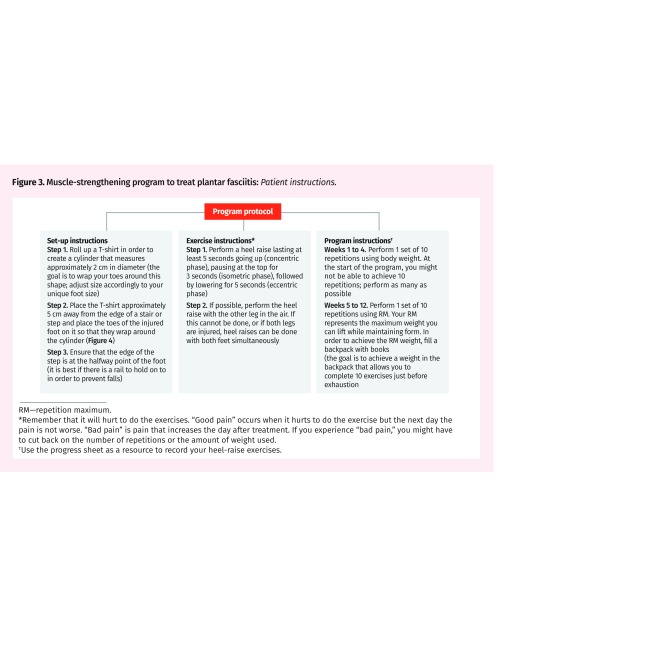

In this article we will describe a muscle-strengthening program that involves progressive eccentric and concentric resistance exercises for the treatment of PF. While this HLST muscle-strengthening program can be used in conjunction with other prescribed PF therapies (eg, weight loss, other types of stretches, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other treatments noted in the introduction), it can also be considered a stand-alone therapy to treat the symptoms of PF. The exercise can be done at home and requires items commonly found around the house.

Muscle-strengthening program

This HLST muscle-strengthening program was initially proposed by Rathleff and colleagues,9 and encompasses concentric and eccentric heel-raise exercises designed to treat PF. However, we have modified aspects of the program in order to simplify its execution for patients in the clinical or home-based settings (Figure 3).* In order to increase patient compliance and reduce dropout, we have also created a progress sheet that patients can use to record the completion of daily exercises (available at CFPlus).* From our experience, we found that the original protocol of the program was difficult for patients to comprehend and maintain, especially owing to the multiple numbers of changing sets. By simplifying the protocol we have seen improved adherence and therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 3.

Muscle-strengthening program to treat plantar fasciitis: Patient instructions.

RM—repetition maximum.

*Remember that it will hurt to do the exercises. “Good pain” occurs when it hurts to do the exercise but the next day the pain is not worse. “Bad pain” is pain that increases the day after treatment. If you experience “bad pain,” you might have to cut back on the number of repetitions or the amount of weight used.

†Use the progress sheet as a resource to record your heel-raise exercises.

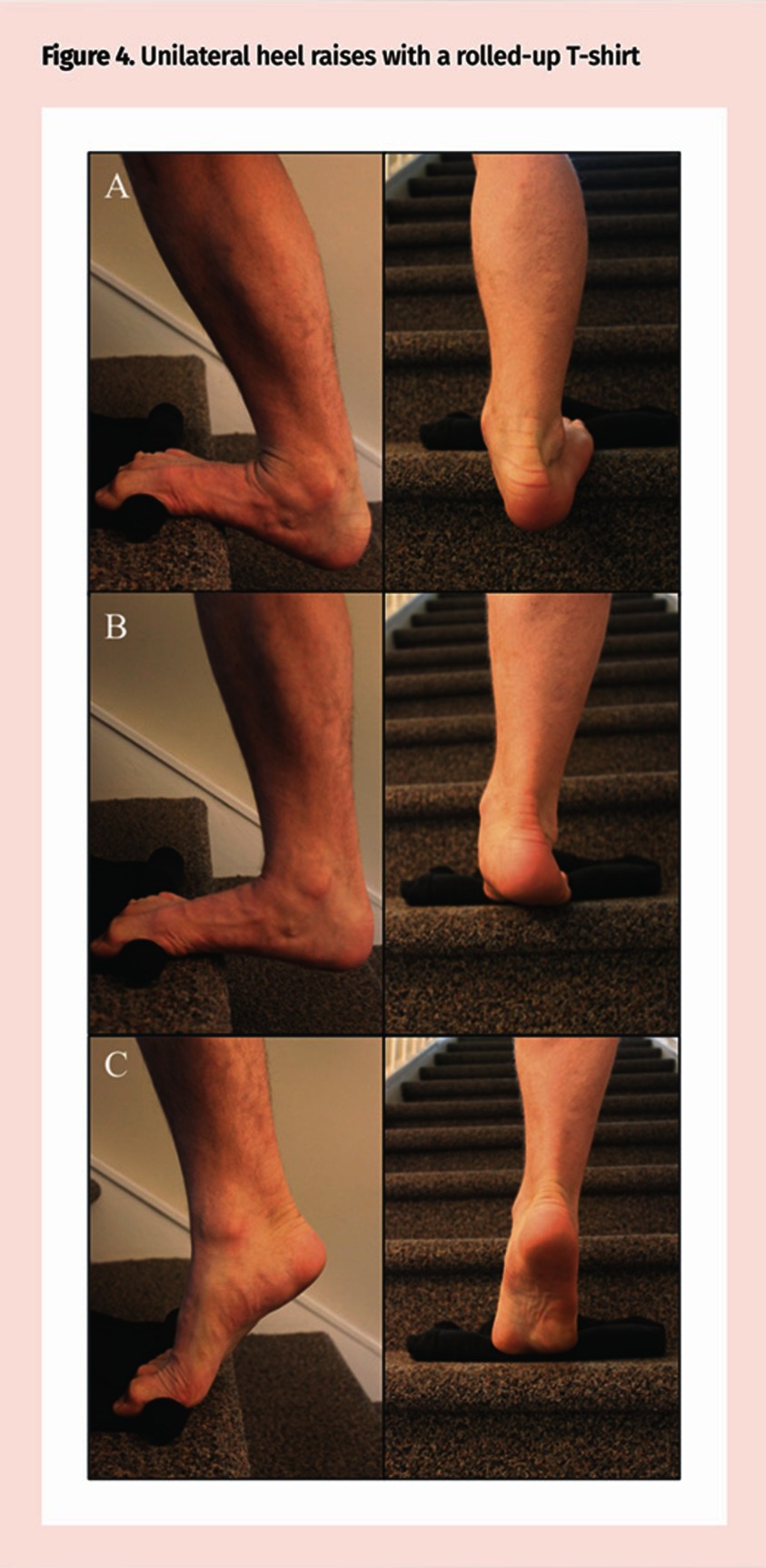

We recommend that the following exercises be performed daily for a minimum of 3 months or until pain cessation (Figure 3). Previous articles have recommended the use of a towel for toe grip.9 However, based on our experiences with patients, we found that a towel is not ideal for toe gripping owing to its thickness. Rather, it is better to use a rolled-up cotton T-shirt, as this has the benefit of being easily manipulated to a patient’s individual build owing to its pliable nature (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Unilateral heel raises with a rolled-up T-shirt

Discussion

The rationale for the protocol of this regimen is that stressing the plantar fascia through progressive concentric and eccentric resistance exercises (using the windlass mechanism in combination with Achilles tendon loading) can stimulate increased collagen synthesis. Collagen type 1 fibres, which make up the plantar fascia, respond to high-load tension with increased collagen synthesis.10 In patients with PF, this has the potential to heal the degenerative changes seen at the plantar fascia enthesis, leading to a more normalized tendon structure, less pain, and, ultimately, improved patient outcomes. An additional benefit observed in individuals who participate in this protocol is the potential for increased ankle dorsiflexion strength.9 This can counteract the typical decline in ankle dorsiflexion strength observed in those with PF.11

Limitations and future directions

One difficulty preventing optimal PF treatment is the current confusion regarding the cause and pathophysiology of the disorder.12 There is still debate as to whether PF results from an inflammatory or degenerative process, which might explain why current treatments (eg, steroid injections) might not be as effective as expected.12 Furthermore, as PF is diagnosed based mainly on history and elicitation of pain on the plantar aspect of the heel, additional investigation might be required in order to determine whether different subpopulations of PF patients exist (eg, the diagnosis of plantar fascia rupture could present with similar symptoms but requires investigation with magnetic resonance imaging).13 This could explain the variable efficacies of different treatments, as well as the current debate regarding the pathophysiology of PF.

Despite the efficacy of this protocol in previous studies and in our practice compared with other treatment paradigms,9,10 a small population of patients might continue to experience ongoing symptoms after using this protocol. This is a pattern that has been seen across most of the treatments for PF and is normal. If symptoms continue beyond a period of 6 months using this treatment protocol, patients should visit their family physician in order to pursue other potential treatment options.

Conclusion

We have presented a previously validated treatment protocol for PF with modifications in order to optimize efficacy and treatment outcomes for patients living with PF. The HLST regimen we have described is inexpensive, convenient, and, in our experience, very effective for treating the symptoms of PF. It also addresses the large number of patients who continue to experience PF-related symptoms despite conventional treatments. Finally, it is important that patients are compliant with the training paradigm and have some tolerance for pain. They should be counseled about the exacerbation of pain when performing the exercises, and should also be provided with handouts to enable them to safely follow the program’s protocol at home, as well as track their exercise regimen (CFPlus).*

We encourage readers to share some of their practice experience: the neat little tricks that solve difficult clinical situations. Praxis articles can be submitted online at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/cfp or through the CFP website (www.cfp.ca) under “Authors and Reviewers.”

Footnotes

An easy-to-print handout of Figure 3, as well as a progress sheet that is available in English for patients to track completion of heel-raise exercises, is available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Competing interests

None declared

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de janvier 2018 à la page e19.

References

- 1.Dunn JE, Link CL, Felson DT, Crincoli MG, Keysor JJ, McKinlay JB. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(5):491–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill CL, Gill TK, Menz HB, Taylor AW. Prevalence and correlates of foot pain in a population-based study: the North West Adelaide health study. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008;1(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo B. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(2):95–101. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan KM, Cook JL, Kannus P, Maffulli N, Bonar SF. Time to abandon the “tendinitis” myth. BMJ. 2002;324(7338):626–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7338.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stecco C, Corradin M, Macchi V, Morra A, Porzionato A, Biz C, et al. Plantar fascia anatomy and its relationship with Achilles tendon and paratenon. J Anat. 2013;223(6):665–76. doi: 10.1111/joa.12111. Epub 2013 Sep 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young CC, Rutherford DS, Niedfeldt MW. Treatment of plantar fasciitis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(3):467–74. 477–8. Erratum in: Am Fam Physician 2001;64(4):570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goff JD, Crawford MD. Diagnosis and treatment of plantar fasciitis. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(6):676–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Digiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, Graci PA, Williams TT, Wilding GE, et al. Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1775–81. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rathleff MS, Mølgaard CM, Fredberg U, Kaalund S, Andersen KB, Jensen TT, et al. High-load strength training improves outcome in patients with plantar fasciitis: a randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(3):e292–300. doi: 10.1111/sms.12313. Epub 2014 Aug 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langberg H, Ellingsgaard H, Madsen T, Jansson K, Magnusson SP, Aagaard P, et al. Eccentric rehabilitation exercise increases peritendinous type I collagen synthesis in humans with Achilles tendinosis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17(1):61–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00522.x. Epub 2006 Jun 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel A, DiGiovanni B. Association between plantar fasciitis and isolated contracture of the gastrocnemius. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(1):5–8. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: a degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(3):234–7. doi: 10.7547/87507315-93-3-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxena A, Fullem B. Plantar fascia ruptures in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(3):662–5. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]