Key Points

Question

What is the association of prior authorization and copay with patient access to PCSK9 inhibitors among those who are prescribed therapy?

Findings

In this observational analysis, in the first year of PCSK9 inhibitors availability, only 47.2% of patients prescribed PCSK9 inhibitors received insurance approval for therapy, and of those, 34.7% never filled the prescription from the pharmacy. Prescription abandonment was largely explained by out-of-pocket cost.

Meaning

Less than one-third of patients prescribed PSCK9 inhibitors therapy never received therapy owing to a combination of lack of insurance approval and cost sharing.

Abstract

Importance

Although PCSK9 inhibitors (PCSK9i) were approved in 2015, their high cost has led to strict prior authorization practices and high copays, and use of PSCK9i in clinical practice has been low.

Objective

To evaluate patient access to PCSK9i among those prescribed therapy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Using pharmacy transaction data, we evaluated 45 029 patients who were newly prescribed PCSK9i in the United States between August 1, 2015, and July 31, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The proportion of PCSK9i prescriptions approved and abandoned (approved but unfilled); multivariable analyses examined factors associated with approval/abandonment including payor, prescriber specialty, pharmacy benefit manager, out-of-pocket cost (copay), clinical diagnoses, lipid-lowering medication use, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels.

Results

Of patients given an incident PCSK9i prescription, 51.2% were women, 56.6% were 65 years or older, and 52.5% had governmental insurance. Of the patients given a prescription, 20.8% received approval on the first day, and 47.2% ever received approval. Of those approved, 65.3% filled the prescription, resulting in 30.9% of those prescribed PCSK9i ever receiving therapy. After adjustment, patients who were older, male, and had atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease were more likely to be approved, but approval rates did not vary by patient low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level nor statin use. Other factors associated with drug approval included having government vs commercial insurance (odds ratio [OR], 3.3; 95% CI, 2.8-3.8), and those filled at a specialty vs retail pharmacy (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.66-2.33). Approval rates varied nearly 3-fold among the top 10 largest pharmacy benefit managers. Prescription abandonment by patients was most associated with copay costs (C statistic, 0.86); with abandonment rates ranging from 7.5% for those with $0 copay to more than 75% for copays greater than $350.

Conclusions and Relevance

In the first year of availability, only half of patients prescribed a PCSK9i received approval, and one-third of approved prescriptions were never filled owing to copay.

This study evaluates patient access to PCSK9 inhibitors among those prescribed therapy.

Introduction

Since 2015, 2 PCSK9 inhibitors (PCSK9i), alirocumab and evolocumab, have been approved for adults with persistently elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels despite maximally tolerated statin therapy and those with familial hypercholesterolemia. The retail cost for these PCSK9i can be as much as $14 000 per year, leading health insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to implement utilization management processes including prior authorization and patient therapy copays. To date, limited empirical information is available on how these preauthorization processes and copays jointly are associated with access to PCSK9i in community practice.

In this analysis, we evaluated what proportion of patients prescribed PCSK9i ultimately received therapy and factors associated with both approval and dispensing in the first year after PCSK9i were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Specifically, we calculated the proportion of patients who received a rejection initially (within 24 hours) as well as the proportion who ultimately received approval. We also examined the proportion of approved prescriptions that were filled vs left at the pharmacy (abandoned) and determined the duration between initial prescription and medication dispense. Next, we examined what factors were associated with an increased odds of receiving therapy. Finally, we examined the association between patient copay and prescription abandonment.

Methods

Data Description

Using pharmacy claims transactional data from Symphony Health Solutions, we evaluated new PCSK9i prescriptions from August 1, 2015, through July 31, 2016. The Symphony Health Solutions database captures full life cycle pharmacy claims data from initial submission of a prescription through its final disposition from more than 90% of retail, 60% of mail-order, and 70% of specialty pharmacies in the United States. Pharmacy-level transmissions are date and time stamped and include whether (1) the claim was rejected or approved; (2) the patient filled the prescription (dispensed) or left it at the pharmacy after it was approved (abandoned); and (3) secondary insurance or a coupon program was used to defray the patient’s copay. Available patient characteristics included sex, age, payor(s), PBM(s), prescribing clinician taxonomy code, and pharmacy type used. The payor associated with a patient was determined by evaluating all payors for which prescription claims were processed for a given patient during the prescription episode. Payor types were split into commercial or government (including Veterans Affairs, Tricare, Medicare, Managed Medicaid, and Medicaid).

Pharmacy transaction data at the patient level were linked to electronic health record and claims data for a subset of patients. Among patients with electronic health record and claims linkages, we identified adults with a diagnosis of prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) on the day of or prior to the first prescription for a PCSK9i. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease was defined as a diagnosis of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease (prior stroke, transient ischemic attack, and carotid stenosis), peripheral arterial disease, or other atherosclerotic vascular disease on the day of or prior to the PCSK9i prescription. eTable 1 in the Supplement lists the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes used to classify patient diagnoses. Medication data were used to identify adults with an active prescription for a statin, a high-intensity statin (atorvastatin ≥ 40 mg or rosuvastatin ≥ 20 mg), ezetimibe, or other lipid-lowering therapy at the time of PCSK9i prescription. Follow-up was available from August 1, 2015, through August 31, 2016.

The unit of analysis was at the patient level because patients could be issued multiple or redundant prescriptions for the same medication or could be prescribed 2 different PCSK9i types and because individual prescriptions were often submitted and resubmitted multiple times in succession, either for administrative reasons (eg, wrong date of birth) or clinical appeals. The first transaction for any PCSK9i prescription for a patient was considered the prescribing date, with the first prescription episode defined as the time between the prescribing date and first PCSK9i dispense for those who received medication, the time between the prescribing date and first approval for abandoned prescriptions, and the time between prescribing date and last rejection for those who were never approved.

This study was approved by the Duke University institutional review board. Informed consent was not required because this analysis used deidentified data from Symphony Health Solutions.

Factors Associated With Approval

We evaluated ultimate approval and dispense rates, as well as approval rates in the first 24 hours after a prescription was submitted, for all prescriptions between August 1, 2015, and July 31, 2016. Approval rates in the first 24 hours were used to determine the proportion of prescriptions filled on initial attempt vs those that were approved later with appeals or resubmissions of claims over time. Next, differences in approval rates were evaluated by pharmacy type (retail, mail order, institutional, or specialty), payor type (government, commercial, government and commercial, or other/none), and clinician type (cardiology, endocrinology, general practice including family medicine and internal medicine, and other), which were defined by clinician taxonomy codes. Multivariable logistic regression modeling was used to evaluate factors associated with receiving approval for medication, and included age, sex, payor type, prescriber specialty, and pharmacy type. In addition, to evaluate differences in approval rates by PBM, the model included indicator variables for the top 10 PBMs volume of patients prescribed PSCK9i therapy in the sample.

To evaluate the association of clinical factors and medication use with approvals, the multivariable model of approvals was rerun for the subsample of patients on whom clinical and medication data were available. A further subset of patients had linked laboratory data available with at least 1 LDL-C value in the prior year. Approval rates by most recent LDL-C level were evaluated for this subset of patients by evaluating the odds of approval at different LDL-C levels adjusting for patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and payor factors as in prior logistic regression models. To assess the degree to which clinical, medication, and laboratory data were associated with approvals, the C statistics from this full model and a model without diagnoses, laboratory, and medication data were calculated.

Factors Associated With Dispensing After Approval

To allow for comparison of out-of-pocket costs when variable medication quantities were issued to patients, copay was defined as a patient’s out-of-pocket cost for a 1-month supply of medication after any insurance claim, coupon, or patient assistance programs. To evaluate the relationship between copay and abandonment (prescription approved but not picked up at the pharmacy), the proportion of prescriptions dispensed (vs abandoned) by percentile of copay was evaluated for approved prescriptions. Next, a multivariable logistic regression model was created to evaluate the association between copay and prescription dispensing (vs abandonment), first alone and then after adjusting for age, sex, payor type, prescriber specialty, pharmacy type, and time to first approval. Owing to the nonlinear relationship between patient copay and prescription abandonment, the association between copay and prescription dispensing was modeled using restricted cubic splines with knots at the 40th, 60th, and 80th percentiles. Because copay is modeled with restricted cubic splines, odds ratios (ORs) for specific copays are displayed. The C statistic for this full multivariable logistic regression model was calculated in addition to the C statistic for a model using only copay to determine the degree to which copay alone affected prescription abandonment.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and STATA SE 14.2 (STATACorp).

Results

Population Description and Rates of Rejection, Approvals, and Dispensing

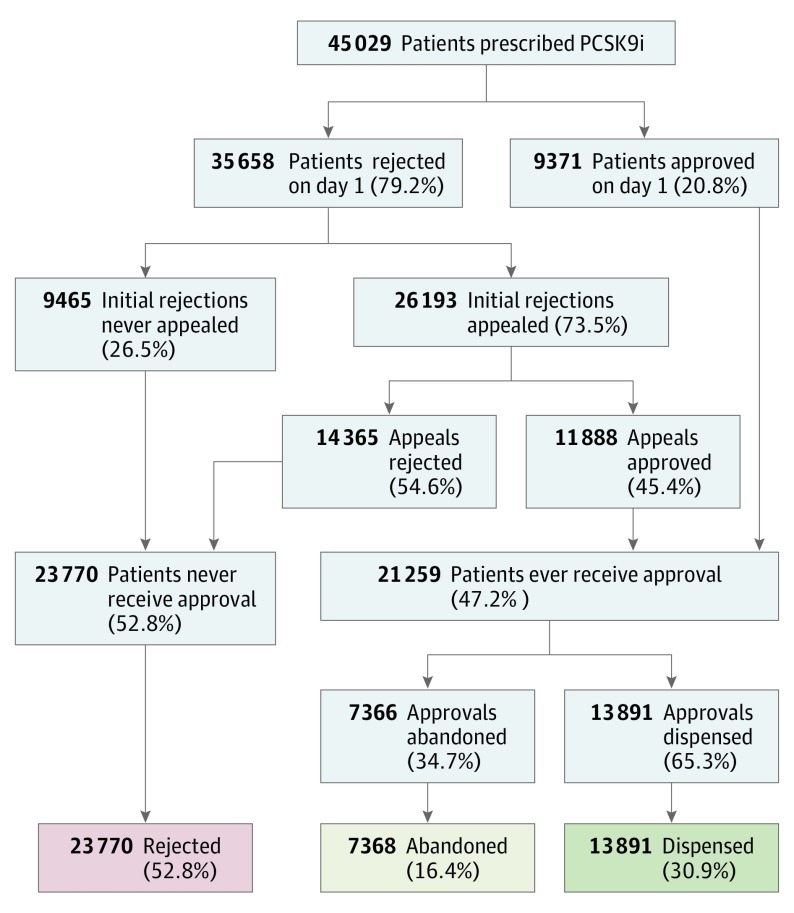

We analyzed 45 029 patients initially prescribed a PCSK9i between August 1, 2015, and July 31, 2016, in the Symphony Health Solutions data. In the first day following submission of the incident prescription, 35 658 patients (79.2%) were initially rejected and 20.8% were approved. Of those rejected, 73.5% (n = 26 193) were appealed or resubmitted, after which an additional 11 888 (45.4% of appeals and 26.4% of all patients) received approval, leading to an ultimate approval rate of 47.2% (Figure 1). Among 21 259 patients who received approval, 7368 (34.7% of those who received approval) never picked up the medication and therefore were considered “abandoned.” Ultimately, 13 891 of 45 029 patients (30.9%) initially prescribed a PCSK9i actually received therapy (Figure 1). The median time between initial submission and approval was 3.9 days (interquartile range, 0-20.0). However, approval times were more prolonged for other patients; 17.2% of patients waited 30 days or more, the top 10% of patients waited at least 52 days, and the top 5% waited 87 days or longer for approval (eFigure in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Rejections, Dispenses, and Abandonment in Patients Initially Prescribed Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibitors (PCSK9i).

Table 1 shows characteristics of patients prescribed PCSK9i by those receiving initial (first-day) prescription approval and those who received ultimate approval. Most patients (23 652; 52.5%) had government insurance, and of those with government insurance, 89.8% had Medicare. Commercial insurers covered 40.0% of patients (n = 17 999), and 4.5% (n = 2043) had both commercial and government insurance. Retail pharmacies were most commonly used (35 234; 78.2%), although nearly one-fifth of prescriptions were filled through a specialty pharmacy. A total of 18 398 unique physicians wrote prescriptions for PSCK9i, with median of 1 (interquartile range, 1-3) patient per physician. Nearly half of those patients were prescribed therapy by a cardiologist (48.3%), followed by general practitioners (36.8%).

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients Prescribed PCSK9i, First-Day Approval, and Ultimate Approval Rates.

| Parameters | No. of Patients (% Sample) | Patients Approved Day 1, No. (%) |

Patients Ever Receiving Approval, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | 45 029 (100) | 9371 (20.8) | 21259 (47.2) |

| Age, y | |||

| <45 | 1702 (3.8) | 251 (14.7) | 469 (27.6) |

| 45-54 | 5239 (11.6) | 814 (15.5) | 1736 (33.1) |

| 55-64 | 12 591 (28.0) | 2084 (16.6) | 4441 (35.3) |

| 65-74 | 16 660 (37.0) | 4041 (24.3) | 9435 (56.6) |

| ≥75 | 8837 (19.6) | 2181 (24.7) | 5178 (58.6) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 23 065 (51.2) | 4788 (20.8) | 10905 (47.3) |

| Male | 21 964 (48.8) | 4583 (20.9) | 10354 (47.1) |

| Pharmacy | |||

| Retail | 35234 (78.2) | 6173 (17.5) | 14882 (42.2) |

| Institutional | 239 (0.5) | 37 (15.5) | 102 (42.7) |

| Mail-order pharmacy | 255 (0.6) | 199 (78.0) | 218 (85.5) |

| Specialty | 9300 (20.7) | 2962 (31.8) | 6057 (65.1) |

| Clinician | |||

| Cardiologist | 21 767 (48.3) | 4844 (22.3) | 11485 (52.8) |

| General practitioner | 16 593 (36.8) | 3112 (18.8) | 6740 (40.6) |

| Endocrinologist | 2234 (5.0) | 428 (19.2) | 997 (44.6) |

| Other clinician | 4435 (9.8) | 987 (22.3) | 2037 (45.9) |

| PBM | |||

| PBM 1 | 3303 (7.3) | 1118 (33.8) | 2211 (66.9) |

| PBM 2 | 500 (1.1) | 98 (19.6) | 195 (39.0) |

| PBM 3 | 1358 (3.0) | 176 (13.0) | 519 (38.2) |

| PBM 4 | 8196 (18.2) | 1346 (16.4) | 3233 (39.4) |

| PBM 5 | 8540 (19.0) | 1298 (15.2) | 3112 (36.4) |

| PBM 6 | 8054 (17.9) | 1943 (24.1) | 5383 (66.8) |

| PBM 7 | 1062 (2.4) | 170 (16.0) | 478 (45.0) |

| PBM 8 | 8163 (18.1) | 1371 (16.8) | 3632 (44.5) |

| PBM 9 | 2833 (6.3) | 430 (15.2) | 1087 (38.4) |

| PBM 10 | 617 (1.4) | 18 (2.9) | 156 (25.3) |

| Payor | |||

| Commercial | 17 999 (40.0) | 2489 (13.8) | 5111 (28.4) |

| Government | 23 652 (52.5) | 5767 (24.4) | 14236 (60.2) |

| Government and commercial | 2043 (4.5) | 332 (16.3) | 1084 (53.1) |

| Other | 1335 (3.0) | 783 (58.7) | 828 (62.0) |

| Clinical | |||

| Overall clinical subsample | 17,851 | 3688 (20.7) | 8738 (48.9) |

| Any ASCVD | 12 186 (68.3) | 2657 (21.8) | 6362 (52.2) |

| CAD | 10 869 (60.9) | 2359 (21.7) | 5708 (52.5) |

| PAD | 3262 (18.3) | 753 (23.1) | 1780 (54.6) |

| CVD | 4235 (23.7) | 952 (22.5) | 2296 (54.2) |

| Statin | |||

| High intensity | 2071 (11.6) | 425 (20.5) | 1012 (48.9) |

| Low to moderate intensity | 2053 (11.5) | 393 (19.1) | 1001 (48.8) |

| No statin | 13727 (76.9) | 2870 (20.9) | 6725 (49.0) |

| Ezetimibe | |||

| Yes | 1874 (10.5) | 389 (20.8) | 972 (51.9) |

| No | 15 977 (89.5) | 3299 (20.6) | 7766 (48.6) |

| Other LLT | |||

| Yes | 2072 (11.6) | 445 (21.5) | 1054 (50.9) |

| No | 15 779 (88.4) | 3243 (20.6) | 7684 (48.7) |

| Laboratories | |||

| Overall laboratory subsample | 5383 (100.0) | 1089 (20.2) | 2637 (49.0%) |

| <70 | 548 (10.2) | 139 (25.4) | 286 (52.2) |

| 70-99 | 726 (13.5) | 160 (22.0) | 368 (50.7) |

| 100-129 | 1031 (19.2) | 219 (21.2) | 528 (51.2) |

| 130-159 | 1246 (23.1) | 228 (18.3) | 621 (49.8) |

| 160-189 | 941 (17.5) | 174 (18.5) | 435 (46.2) |

| ≥190 | 891 (16.6) | 169 (19.0) | 399 (44.8) |

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PBM, pharmacy benefit manager; PCSK9i, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors.

Among those with clinical data available (n = 17 851; 39.6% of the sample), 68.3% had a diagnosis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (n = 12 186), the most common of which was coronary artery disease (n = 10 869; 60.9%, Table 1). Lipid-lowering therapy use was infrequent at the time of PCSK9i prescription, with only 23.1% receiving a statin (2071 [11.6%] receiving high intensity and 2053 [11.5%] receiving low/moderate intensity), 10.5% receiving ezetimibe (n = 1874), and 11.6% receiving another form of lipid-lowering therapy (n = 2072). In the subsample of patients with laboratory data available and an LDL-C value within the last year (n = 5383), 16.6% had an LDL-C value greater than 190 mg/dL (n = 891), 17.5% between 160 and 189 mg/dL (n = 941), and 10.2% less than 70 mg/dL (n = 548; to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259). Of note, patient characteristics as well as approval rates were generally similar among those who had clinical and/or laboratory data available as was seen in the overall patient sample (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Factors Associated With Receiving Ultimate Prescription Approval

In multivariable modeling, several demographic, clinical, and payor factors were associated with the likelihood that a PCSK9i prescription would be approved. Table 2 provides the ORs for ultimate approval among the subsample of patients with laboratory and clinical data available (n = 5383); however, the magnitude and direction of these associations were similar in the overall patient sample and among those with clinical data only (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Patients who were older and men were more likely to have their prescription approved than their counterparts. Adults with prior ASCVD were more likely to receive approval for therapy than adults without a diagnosis of ASCVD (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.04-1.35), yet there was no difference in odds of approval seen in those receiving a high-intensity statin (vs no statin, OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.9-1.2), a low/moderate–intensity statin (vs no statin, OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4), nor by the patient’s most recent LDL-C level to the time of PCSK9i prescription. Those receiving ezetimibe were more likely to receive approval (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.6).

Table 2. Predictors of Approval Among Patients With Laboratory, Clinical, and Medication Data.

| Patients (N = 5383) | Multivariable Results for Ever Receiving Approval, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age, y (reference: <45) | |

| 45-54 | 1.31 (0.87-1.98) |

| 55-64 | 1.48 (1.00-2.19) |

| 65-74 | 1.90 (1.28-2.82) |

| ≥75 | 1.79 (1.19-2.69) |

| Female vs male | 0.95 (0.84-1.08) |

| Pharmacy | |

| Specialty vs retail | 1.96 (1.66-2.33) |

| Mail order | 6.43 (2.67-15.50) |

| Institutional | 4.98 (1.83-13.60) |

| Specialty (reference: general) | |

| Cardiologist | 1.42 (1.24-1.63) |

| Endocrinologist | 1.03 (0.75-1.42) |

| Other | 1.37 (1.08-1.73) |

| Payor (reference: commercial) | |

| Government | 3.27 (2.79-3.83) |

| Government and commercial | 2.6 (1.95-3.46) |

| PBM | |

| PBM 1 | 2.32 (1.73-3.13) |

| PBM 2 | 1.15 (0.67-1.98) |

| PBM 3 | 0.95 (0.66-1.37) |

| PBM 4 | 0.75 (0.6-0.93) |

| PBM 5 | 0.76 (0.61-0.94) |

| PBM 6 | 1.19 (0.94-1.5) |

| PBM 7 | 1.32 (0.92-1.92) |

| PBM 8 | 0.77 (0.62-0.95) |

| PBM 9 | 1.22 (0.92-1.62) |

| PBM 10 | 0.54 (0.32-0.9) |

| Indication | |

| Prior ASCVD vs primary | 1.18 (1.04-1.35) |

| Medication | |

| High-intensity statin vs no statin | 1.03 (0.85-1.24) |

| Low/moderate statin vs no statin | 1.14 (0.94-1.38) |

| Ezetimibe vs none | 1.29 (1.07-1.56) |

| Other LLT vs none | 1.22 (1.01-1.48) |

| Last LDL-C, mg/dL (reference: <70 mg/dL) | |

| 70-99 | 0.93 (0.73-1.19) |

| 100-129 | 0.94 (0.74-1.18) |

| 130-159 | 0.92 (0.73-1.15) |

| 160-189 | 0.89 (0.7-1.12) |

| ≥190 | 0.9 (0.71-1.15) |

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; OR, odds ratio; PBM, pharmacy benefit manager; PCSK9i, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors.

SI conversion factor: To convert LDL-C to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259.

Patients with prescriptions written by general practitioners had the lowest approval rates, while those from cardiologists had the highest chance of success (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.24-1.63 for cardiology vs general practice). Patients who had prescriptions processed by specialty pharmacies were more likely to be approved than retail pharmacies (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.66-2.33). Patients with government insurance plans had a higher odds of approval than those with commercial insurance (OR, 3.27; 95% CI, 2.79-3.83).

The likelihood for prescription approval also varied significantly by which PBM was used (Table 2). In fact, knowing patient age, sex, pharmacy type, prescriber type, payor, and PBM could correctly discriminate ultimate approval in 72% of cases (C statistic, 0.721). Including laboratory, medication, and diagnoses data only increased the model prediction to a C statistic of 0.737.

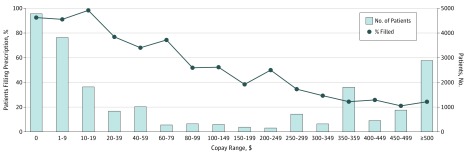

Factors Associated With Abandonment of Approved Prescriptions

Among patients who received approval for therapy (n = 21 259), 7368 (34.7%) never filled the prescription. Patient copays ranged from $0 to $2822 per month supply, with a median of $15 and interquartile range of $15 to $373. Figure 2 demonstrates the association between patient copays and the proportion of patients who had therapy dispensed. Overall, 23% of patients with approved prescriptions had a $0 copay (n = 4781); of these, 92.6% of patients (n = 4425) picked up the medication from the pharmacy. The rate of dispensing dropped as copays increased until around $350, after which, dispensing rates were flat between 20% to 25%. Once the prescription was approved, copay alone was highly predictive of whether a patient would fill their prescription; the C statistic was 0.86 for the logistic regression model evaluating the association between copay and prescription abandonment with copay alone. Including payor, clinician, time to approval, and pharmacy type only marginally increased model performance (C statistic for multivariable model, 0.87).

Figure 2. Relationship Between Copay and Prescription Abandonment for Patients Approved for Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibitors (PCSK9i) Therapy.

Proportion of patients who filled their prescription after approval by range of copay (black line with markers), and the number of patients whose out of pocket costs were in that range (gray bars). Copay reflects ultimate out of pocket costs after co-insurance, patient approval program use, and coupon use.

After adjusting for patient demographics, pharmacy, prescribing clinician, and payor, copay remained highly predictive of whether a patient would pick up the medication from the pharmacy after it was approved. Table 3 shows the proportion of prescriptions dispensed after approval by subgroup, and results from multivariable logistic regression of factors associated with prescription dispensing after approval. Compared with patients who had no out-of-pocket costs, those with a $10 copay had a 19% lower odds of filling their prescription (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.81-0.82), and those with a $100 copay had a 84% lower odds (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.15-0.17; Table 3). In addition to higher copay, women, those with government insurance, use of a specialty pharmacy, and increased times to approval were associated with lower rates of medication dispensing in multivariable modeling.

Table 3. Percentage of Approved Prescriptions Dispensed and Factors Associated WIth Dispensing After Approval Among Approved Prescriptions.

| Subgroup | No. Approved | Dispensed After Approval, No. (%) |

Multivariable Results for Dispensing After Approval, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 21 259 | 13 891 (65.3) | NA |

| Age, y | |||

| <45 | 469 | 367 (78.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| 45-54 | 1736 | 1422 (81.9) | 1.06 (0.76-1.47) |

| 55-64 | 4441 | 3414 (76.9) | 1.02 (0.75-1.39) |

| 65-74 | 9435 | 5687 (60.3) | 1.11 (0.82-1.50) |

| >75 | 5178 | 3001 (58.0) | 1.02 (0.75-1.39) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 10 905 | 6940 (67.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 10 354 | 6951 (63.7) | 0.83 (0.77-0.89) |

| Pharmacy | |||

| Retail | 14 882 | 9982 (67.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Institutional | 102 | 74 (72.6) | 1.41 (0.81-2.47) |

| Mail order | 218 | 159 (72.9) | 3.44 (1.82-6.49) |

| Specialty | 6057 | 3676 (60.7) | 0.89 (0.82-0.97) |

| Clinician type | |||

| General practice | 6740 | 4261 (63.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| Cardiology | 11 485 | 7539 (65.6) | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) |

| Endocrinology | 997 | 660 (66.2) | 1.06 (0.87-1.28) |

| Other | 2037 | 1431 (70.2) | 1.49 (1.29-1.72) |

| Payor type | |||

| Commercial only | 5111 | 4071 (79.7) | 1 [Reference] |

| Government only | 14 236 | 8418 (59.1) | 0.57 (0.50-0.64) |

| Commercial and government | 1084 | 762 (70.3) | 0.68 (0.55-0.83) |

| Other | 828 | 640 (77.3) | 1.17 (0.91-1.51) |

| Copay, $ | NAa | NAa | 1 [Reference] |

| 10 | NAa | NAa | 0.81 (0.81-0.82) |

| 20 | NAa | NAa | 0.66 (0.65-0.67) |

| 40 | NAa | NAa | 0.44 (0.43-0.45) |

| 100 | NAa | NAa | 0.16 (0.15-0.17) |

| 200 | NAa | NAa | 0.06 (0.05-0.06) |

| 300 | NAa | NAa | 0.04 (0.03-0.04) |

| 500 | NAa | NAa | 0.03 (0.03-0.03) |

| Time to approval, d | |||

| 0-1 | 9858 | 6620 (67.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| 2-7 | 2829 | 1908 (67.4) | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) |

| 8-14 | 2263 | 1432 (63.3) | 0.90 (0.79-1.03) |

| 15-31 | 2647 | 1602 (60.5) | 0.74 (0.65-0.83) |

| >1 mo | 3662 | 2329 (63.6) | 0.78 (0.70-0.87) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Multivariable model results from copay reflects ultimate out of-pocket costs after co-insurance, patient approval program use, and coupon use. Because copay was modeled using restricted cubic splines, representative ORs are presented at each copay level. See Figure 2 for absolute dispense rates by copay ranges.

Discussion

The high retail cost of PCSK9i therapy has led to significant debate about their cost-effectiveness and optimal price points. In response to these costs, payors have implemented various utilization management strategies including prior authorization requirements and patient cost-sharing (copays). While these strategies have contained costs, our analysis suggests that these practices may be a blunt instrument to identify those at highest risk or those who may benefit the most.

Our study was not designed to address the appropriateness of current drug prices; rather, our analyses address the degree to which utilization management and patient out-of-pocket costs were associated with the likelihood that a patient prescribed therapy by their physician would ultimately receive this therapy. In the first year of PSCK9i availability, fewer than 1 in 3 adults initially prescribed PCSK9i therapy actually received it: 52.8% never received approval, and 34.7% of those approved never filled the prescription. While those with ASCVD were slightly more likely to receive approval than those without, there was no difference in approval rates by statin use or LDL-C levels. In contrast, nonclinical factors, such as the patient’s payor type, PBM, and type of pharmacy used, all strongly were associated with the likelihood that a prescription would be approved. Once approved, out-of-pocket costs were the primary driver of prescription abandonment.

Clinicians and pharmacy type both were associated with the success of initial prescriptions. Cardiologists were more successful than other clinicians in obtaining approval for PCSK9i, which may indicate that subspecialists were better able to select patients who met these criteria. Alternately, the increased volume of prescriptions written by cardiologists may have allowed them to develop support systems to better navigate the complex application and appeal process for their patients. Specialty pharmacies also had higher approval rates, potentially owing to systems to support clinicians in appealing payor rejections.

However, one of strongest factors associated with approval rates was which payor and PBM were involved. This is likely owing to differences in both criteria required for approval and the process itself. While we were unable to determine the proportion of rejections that were clinically appropriate, concerns have been raised by patients and professional societies that the approval process may limit therapy access to those who are clinically indicated. We did find that patients with established ASCVD and patients receiving ezetimibe had a slightly higher odds of receiving approval for PCKS9i. However, we found no difference in approval rates among patients who were receiving any statin or a high-intensity statin and those who were not, nor was there any difference in approval rates by LDL-C levels. Additionally, even after adjusting for these factors, nonclinical factors, such as payor type, PBM, prescriber type, and pharmacy used, remained highly associated with of approval success. One interesting finding was that 10.2% of patients had a most recent LDL-C value less than 70 mg/dL, with just more than half of those patients receiving approval. Although the Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk (FOURIER) trial shows that PCSK9i are effective in those with low-starting LDL-C, most payor criteria at the time required LDL-C to be greater than 70 mg/dL. Whether this represents potential inappropriate prescribing vs patients who later developed statin intolerance remains unclear and should be further studied.

After patients were approved for a medication, we found that up to one-third abandoned the prescription at the pharmacy. This high abandonment rate was almost fully accounted for by differences in patient out-of-pocket costs; fewer than 1 in 10 patients with a $0 copay failed to fill their medication, whereas 3 of 4 patients with a copay exceeding $375 did not pick up their prescription. Furthermore, although the “sticker price” for therapy may be the same for all patients, how much patients actually paid out of pocket varied widely, from $0 for the lowest quartile of patients to more than $300 per month for the highest quartile. Although coupon and patient assistance programs can help offset copay and were used by 38% of patients in this sample, coupon programs are largely unavailable to those with government insurance. Additionally, even after adjusting for copay, patients with government insurance (which was mostly Medicare in this data set) had higher abandonment rates than those with commercial insurance; whether this finding is owing to socioeconomic factors or older age needs further exploration. Although we only assessed a patient’s first fill of PSCK9i, copay also has potential to affect medication persistence and refills and should be studied. This may be particularly relevant to Medicare beneficiaries, who often have fluctuating out-of-pocket costs based on their phase of coverage (eg, before, during, and after the “donut hole”).

Our study also found that the approval process is often prolonged. In 17% of cases, approval was only obtained after more than a month of appeals. This appeal and reapplication process adds significant time to clinicians’ workload. One study estimated that prior authorization requests and appeals in general consume up to 20 hours of staff and professional time per week, per medical practice. Additionally, we found that these delays could affect patients’ likelihood to fill their prescription even if ultimately approved. Specifically, those who waited longer for approval were less likely to pick up the prescription from the pharmacy, even adjusting for copay.

Limitations

The biggest limitation of this study is that it is challenging to fully adjudicate the complex clinical factors used in various PBM approval processes. Thus, we could not fully determine whether specific rejections met these criteria. However, our results suggest that a person’s likelihood of receiving therapy is strongly influenced by payor and PBM dynamics, including differences in payor and PBM policies for approval, which we could not account for in this analysis. Our study had some additional limitations. First, Symphony Health Solutions data do not cover 100% of all pharmacies; however, given the large proportion of US pharmacies that are covered by Symphony Health Solutions, the data we examined likely reflect the experience of most patients prescribed PCSK9i. Second, we evaluated copay as the ultimate out-of-pocket expense. Given the use of coupon cards and patient assistance programs, our analysis reflects out-of-pocket costs rather than the cost share that individual payors are expecting from patients. Finally, we only evaluated prescription patterns in the first year after US Food and Drug Administration approval of PCSK9i. Since then, outcomes trial data from the FOURIER trial have demonstrated the effectiveness of evolocumab, potentially affecting both the rate of prescribing and payor approval criteria.

Conclusions

The high cost of PCSK9 therapy has led payors to institute rigorous prior authorization practices and often leads to high patient copays. In the first year of PCSK9i availability, less than one-third of patients prescribed therapy actually received medication, owing to a combination of high rejection rates and patient abandonment after approval. Even after navigating the approval process, nearly one-third of patients did not pick up their medication, which was mostly explained by patient out-of-pocket cost.

eTable 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes Used to Identify ASCVD

eTable 2. Characteristics of Patients Prescribed PCSK9i in the Overall, Clinical, and Lab Subsample

eTable 3. Factors associated with approval in multivariable analysis, Overall Sample, Clinical, and Lab Subsample

eFigure. Duration from Initial Prescription Submission and Time to Approval

References

- 1.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) BLA approval, BLA 125559. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/125559Orig1s000ltr.pdf. Published July 24, 2015. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- 2.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) BLA approval, BLA 125522/Original 1. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/125522Orig1s000ltr.pdf. Published August 27, 2015. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- 3.Kazi DS, Moran AE, Coxson PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2016;316(7):743-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandra SR, Villa G, Fonarow GC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of LDL-C lowering with evolocumab in patients with high cardiovascular risk in the United States. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(6):313-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mastey V, Johnstone BM. Cost-effectiveness of PCSK9 Inhibitor Therapy. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2151-2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierson R. New cholesterol drugs won't be budget busters: express scripts. Health News September 30, 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-express-scr-cholesterol-idUSKCN0RU2PL20150930. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- 7.Kolata G. Study shows promise for expensive cholesterol drugs, but they are still hard to obtain. New York Times November 15, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/16/health/cholesterol-drugs-pcsk9-inhibitors.html?_r=0. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- 8.Knowles JW, Howard WB, Karayan L, et al. Access to nonstatin lipid-lowering therapies in patients at high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2017;135(22):2204-2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. ; FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators . Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casalino LP, Nicholson S, Gans DN, et al. What does it cost physician practices to interact with health insurance plans? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(4):w533-w543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes Used to Identify ASCVD

eTable 2. Characteristics of Patients Prescribed PCSK9i in the Overall, Clinical, and Lab Subsample

eTable 3. Factors associated with approval in multivariable analysis, Overall Sample, Clinical, and Lab Subsample

eFigure. Duration from Initial Prescription Submission and Time to Approval