Abstract

Vibrio fluvialis, an emerging foodborne pathogen of increasing public health concern, contains two distinct gene clusters encoding type VI secretion system (T6SS), the most newly discovered secretion pathway in Gram-negative bacteria. Previously we have shown that one of the two T6SS clusters, namely VflT6SS2, is active and associates with anti-bacterial activity. However, how its activity is regulated is not completely understood. Here, we report that the global regulator integration host factor (IHF) positively modulates the expression and thus the function of VflT6SS2 through co-regulating its major cluster and tssD2-tssI2 (also known as hcp-vgrG) orphan clusters. Specifically, reporter gene activity assay showed that IHF transactivates the major and orphan clusters of VflT6SS2, while deletion of either ihfA or ihfB, the genes encoding the IHF subunits, decreased their promoter activities and mRNA levels of tssB2, vasH, and tssM2 for the selected major cluster genes and tssD2 and tssI2 for the selected orphan cluster genes. Subsequently, the direct bindings of IHF to the promoter regions of the major and orphan clusters were confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Site-directed mutagenesis combined with reporter gene activity assay or EMSA pinpointed the exact binding sites of IHF in the major and orphan cluster promoters, with two sites in the major cluster promoter, consisting with its two observed shifted bands in EMSA. Functional studies showed that the expression and secretion of hemolysin-coregulated protein (Hcp) and the VflT6SS2-mediated antibacterial virulence were severely abrogated in the deletion mutants of ΔihfA and ΔihfB, but restored when their trans-complemented plasmids were introduced, suggesting that IHF mostly contributes to environmental survival of V. fluvialis by directly binding and modulating the transactivity and function of VflT6SS2.

Keywords: type VI secretion system (T6SS), integration host factor, regulation of gene expression, bacterial killing, Vibrio fluvialis, electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Introduction

The type VI secretion system (T6SS) is the most recently discovered contact-dependent protein secretion system in Gram-negative bacteria (Alteri and Mobley, 2016). Although T6SS is encoded within gene clusters that vary in genetic contents and organization in diverse bacteria (Filloux et al., 2008), a minimal set of 13 core T6SS genes have been recognized (Boyer et al., 2009; Silverman et al., 2012). Structurally, T6SS mimics a contractile phage tail in a topologically reversed orientation (Basler et al., 2012; Ho et al., 2014), and functionally, it acts as a virulence determinant against eukaryotic host cells or is involved in interbacterial interactions and competition functions (Pukatzki et al., 2006, 2007; Russell et al., 2014; Alteri and Mobley, 2016).

The T6SS operating is energetically costly to bacterial cells, so its gene cluster is tightly controlled to adapt its expression and assembly to changing environmental conditions (Journet and Cascales, 2016). Environmental cues, such as temperature (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Salomon et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2017), salinity/osolarity (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2017), iron limitation (Brunet et al., 2011), stresses (Gueguen et al., 2013), cell lysates (LeRoux et al., 2015) etc., affect the expression of T6SS in various species. At present, VasH is the first identified T6SS regulator encoded within the Vibrio cholerae T6SS major cluster, which works as a transactivator of T6SS in V. cholerae together with σ54 (Bernard et al., 2011; Kitaoka et al., 2011). Additional regulators, including ferric-uptake regulator (Fur) and histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS), were found to repress T6SS in different bacterial strains (Brunet et al., 2011; Chakraborty et al., 2011; Salomon et al., 2014; Alteri and Mobley, 2016). Quorum sensing coordinates T6SS expression by repressing it at low cell density through four small RNAs activated by phosphorylated LuxO while upregulating it at high cell density through HapR (Shao and Bassler, 2014; Joshi et al., 2017). A posttranslational regulatory system termed the threonine phosphorylation controls the T6SS expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Mougous et al., 2007). Further defining the activation signals, exploring novel regulators and characterizing the regulatory modules of T6SS are helpful to broaden our understanding of its function in specific bacteria species under the surviving niches and pathogenicity process.

We previously sequenced the whole genome of a clinical isolate of V. fluvialis, an emerging foodborne pathogen of increasing public health concern, whose sequence analysis revealed the existence of T6SS homologous gene clusters (Lu et al., 2014). Subsequently, we characterized the organization, function, and expression regulation of T6SS in V. fluvialis (Huang et al., 2017). We showed that one of the two T6SSs, termed VflT6SS2, is functionally active under low (25°C) and warm (30°C) temperatures. The functional expression of VflT6SS2 is associated with antibacterial activity which is Hcp-dependent and requires the transcriptional regulator VasH as in V. cholerae (Kitaoka et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2017). The genetic composition and organization of VflT6SS2 in V. fluvialis are highly homologous to the T6SS in V. cholerae, except possessing three hcp-vgrG orphan clusters, named tssD2_a-tssI2_a, tssD2_b-tssI2_b and tssD2_c-tssI2_c in V. fluvialis. Mutation analysis found that single deletion of tssD2_a, tssD2_b, or tssDI2_c had no influence on Hcp secretion as well as VflT6SS2-dependent killing of Escherichia coli, but double deletion of tssD2_a and tssD2_b significantly decreased Hcp expression and VflT6SS2’s killing function (Huang et al., 2017). However, the mechanism behind the differential contribution of the three hcps to VflT6SS2 function is still unclear.

Using reporter fusion assays, we firstly showed that tssD2_a has the highest expression level, followed by tssD2_b, and then tssD2_c, and all their expressions are positively controlled by the transcriptional regulator VasH as showed in V. cholerae (Bernard et al., 2011; Kitaoka et al., 2011). Promoter sequence analysis of tssD2-tssI2 alleles and the VflT6SS2 major cluster revealed the existences of consensus recognition sequence of integration host factor (IHF), a specific DNA-binding protein that functions in genetic recombination as well as transcriptional and translational controls (Freundlich et al., 1992). IHF is a heterodimeric protein composed of IHFα and IHFβ subunits encoded by unlinked ihfA and ihfB genes, respectively. Deletion of either ihfA or ihfB results in a significantly reduced transcription of tssD2-tssI2 alleles and the major cluster operon. Consistently, the expression and secretion of Hcp and the VflT6SS2-mediated antibacterial virulence were severely decreased in the ihfA or ihfB mutants, but restored with ihfA or ihfB overexpression from trans-complemented plasmids. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) demonstrated the direct binding of IHF to the promoters of tssD2-tssI2 and VflT6SS2 major cluster. In addition, sequence mutation analysis further confirmed that the regulatory effect relies on the binding of IHF to its consensus recognition sites. In summary, in this study, we made clear the differential expression patterns of tssD2-tssI2 clusters and demonstrated that IHF directly and positively regulates VflT6SS2 expression in V. fluvialis by co-transactivating both the tssD2-tssI2 orphan clusters and the VflT6SS2 major cluster, thus contributing to the survival of bacteria in highly competitive environments.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Culture Conditions, and Plasmids

The wild-type (WT) V. fluvialis 85003 and its derivative mutants were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (pH7.4) containing 1% NaCl (170 mM) at 30°C unless specifically indicated. E. coli DH5αλpir and SM10λpir were routinely cultured at 37°C and used for cloning purposes. Culture media were supplemented with ampicillin (Amp, 100 μg/ml), streptomycin (Sm, 100 μg/ml), tetracycline (Tc, 10 μg/ml for E. coli, 2.5 μg/ml for V. fluvialis), chloramphenicol (Cm, 10 μg/ml), rifampicin (Rfp, 50 μg/ml), or isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) as required. All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain/plasmid | Characteristics | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5αλpir | sup E44ΔlacU169 (ΦlacZΔM15) recA1 endA1 hsdR17 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1pir (Laboratory stock) | Mekalanos Laboratory (Harvard Medical School) |

| SM10λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2Tc::Mu (λpirR6K), KmR | Mekalanos Laboratory (Harvard Medical School) |

| MG1655 | K-12 F- λ- ilvG- rfb-50 rph-1, RfpR | Laboratory stock |

| V. fluvialis | ||

| 85003 | V. fluvialis, wild-type, SmR | Lu et al., 2014 |

| ΔihfA | 85003, ΔihfA | This study |

| ΔihfB | 85003, ΔihfB | This study |

| ΔvasH | 85003, ΔvasH | Huang et al., 2017 |

| ΔihfA/pSRihfA | ΔihfA containing complemented plasmid pSRihfA | This study |

| ΔihfA/pSRKTc | ΔihfA containing control vector pSRKTc | This study |

| ΔihfB/pSRihfB | ΔihfB containing complemented plasmid pSRihfB | This study |

| ΔihfB/pSRKTc | ΔihfB containing control vector pSRKTc | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pWM91 | Suicide vector containing R6K ori, sacB, lacZα; AmpR | Laboratory stock |

| pSRKTc | Broad-host-range vector containing lac promoter, lacIq, lacZα,TetR | Khan et al., 2008 |

| pBBRlux | bioluminescence based reporter plasmid containing a promoterless luxCDABE operon; CmR | Wu et al., 2015 |

| pWM-ΔihfA | 1.69 kb BamHI-XhoI ΔihfA fragment of V. fluvialis in pWM91 | This study |

| pWM-ΔihfB | 1.70 kb BamHI-XhoI ΔihfB fragment of V. fluvialis in pWM91 | This study |

| pSRihfA | 313 bp NdeI-XhoI ihfA ORF of V. fluvialis in pSRKTc | This study |

| pSRihfB | 304 bp NdeI-XhoI ihfB ORF of V. fluvialis in pSRKTc | This study |

| ptssD2a-lux | 375 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of tssD2_a promoter region in pBBRlux | This study |

| ptssD2aM-lux | 375 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of tssD2_a promoter with IHF consensus mutation in pBBRlux | This study |

| ptssD2b-lux | 375 bp SacI-SpeI fragment of tssD2_b promoter region in pBBRlux | This study |

| ptssD2c-lux | 604 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of tssD2_c promoter region in pBBRlux | This study |

| ptssD2c′-lux | 395 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of shortened tssD2_c promoter region in pBBRlux | This study |

| pVflT6SS2-lux | 450 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of VflT6SS2 major cluster promoter region in pBBRlux | This study |

| pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1M | 450 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of VflT6SS2 promoter with mutations in the first IHF binding site in pBBRlux | This study |

| pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf2M | 450 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of VflT6SS2 promoter with mutations in the second IHF binding site in pBBRlux | This study |

| pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf3M | 450 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of VflT6SS2 promoter with mutations in the third IHF binding site in pBBRlux | This study |

| pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1+2M | 450 bp SacI-BamHI fragment of VflT6SS2 promoter with mutations in the first and second IHF binding sites in pBBRlux | This study |

Construction of Transcriptional Reporteeporter Plasmids

Promoter regions of tssD2_a, tssD2_b, tssD2_c, and VflT6SS2 major cluster were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the Prime STAR® HS DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and the products were cloned into pBBRlux, which contains a promoterless luxCDABE reporter. The resultant recombinant constructs were named ptssD2a-lux, ptssD2b-lux, ptssD2c-lux, and pVflT6SS2-lux. ptssD2aM-lux, pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1M, pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf2M, pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf3M, and pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1+2M plasmids, which contain single or double site mutations in the predicted IHF binding sites, were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using ptssD2a-lux, pVflT6SS2-lux or pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1M as a template. Truncated ptssD2c′-lux was yielded by overlap extension PCR using ptssD2c-lux as the template. The detailed information about these constructs is listed in Table 1, and all the constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Primer sequences used here are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Primers | Oligonucleotide sequences (5′-3′)∗ |

|---|---|

| pHcp-up-SacI | CCCGAGCTCAGTCCGTCGCCATCAAATAG |

| pHcp-dn-BamHI | CGGGATCCGAGTTTGACCTTCGATAGAG |

| pHcp-A-up-SacI | CCCGAGCTCTGAGAATAGCCTTCCTTGAC |

| pHcp-B-up-SacI | CCCGAGCTCGTGCCACCTTTGGCTACGTT |

| pHcp-B-dn-SpeI | GGACTAGTGAGTTTGACCTTCGATAGAG |

| pHcp-C′-dn | CCAACTGGGCAATAACAAATAATCAATAAGTT AGCGC |

| pHcp-C′-up | TTGATTATTTGTTATTGCCCAGTTGGCAAGTTAT |

| pHcp-A-M-up | GGCAAGGTTTTAAATATCACTAATACCTTTT AAAAGAATGCCAAAGTGG |

| pHcp-A-M-dn | TTTGGCATTCTTTTAAAAGGTATTAGTGATA TTTAAAACCTTGCCATTAGA |

| pT6SS2-up-SacI | ACGAGCTCACCATGATCTGTTCTGGGAT |

| pT6SS2-dn-BamHI | CGGGATCCTTAGGAGCTACACTTCCTTC |

| pT6SS2-1M-dn | TCTATTCATTTAATCATGTTTACGTGCACAAA AATCACAAGAATA |

| pT6SS2-1M-up | TGATTTTTGTGCACGTAAACATGATTAAATGAA TAGAATGTGCTCG |

| pT6SS2-2M-dn | TTTTTAGTAAATATCACTTCTACCAATTGATTA ATTCACCCGACTT |

| pT6SS2-2M-up | AATTAATCAATTGGTAGAAGTGATATTTACTAA AAATCAAATAAGATA |

| pT6SS2-3M-dn | AATAGTTGTGTCAATATCACCTTGATAATACAC ATTAGAAATATC |

| pT6SS2-3M-up | TGTGTATTATCAAGGTGATATTGACACAACTAT TTCATTGACAAC |

| vflihfA-F1-up-BamHI | CGGGATCCGGAGAGTGAATGAGCCTA |

| vflihfA-F1-dn | TTTTATGGCGGTCGTAAAAAGACCGAGC |

| vflihfA-F2-up | TTTTTACGACCGCCATAAAACTTCCCTC |

| vflihfA-F2-dn-XhoI | CCGCTCGAGTCACCCTGAGCTTGAACG |

| vflihfB-F1-up-BamHI | CGGGATCCTGGTTCGTCGACAAGCTG |

| vflihfB-F1-dn | AAACTATGACCGAAAACATTTGATTTACG |

| vflihfB-F2-up | AATGTTTTCGGTCATAGTTTCCCTCATCG |

| vflihfB-F2-dn-XhoI | CCGCTCGAGCAGTCATTCGCTGAAGCAC |

| vflihfA-F-XhoI | CCGCTCGAGTTACGACTTTTTAATGTTC |

| vflihfA-R-NdeI | GGAATTCCATATGGCGCTCACAAAGGC |

| vflihfB-F-XhoI | CCGCTCGAGTCAAATGTTTTCGTTTACA |

| vflihfB-R-NdeI | GGAATTCCATATGACTAAGTCTGAATTG |

| VF-recA-qPCR-up | ACCGAGTCAACGACGATAAC |

| VF-recA-qPCR-dn | TGATGAACTGCTGGTGTCTC |

| qvipA/tssB2-F | CTGACGACAACAGTGAAGAAC |

| qvipA/tssB2-R | TGCGAAGCCACAGAATCC |

| hcp-qPCR-F-com | TCGGCGATTCATTCGTT |

| hcp-qPCR-R-com | CAGTTCAACCGTCGTCATCT |

| vgrG-qPCR-F-AB | GCATCTTCCAACTCAACAC |

| vgrG-qPCR-R-AB | GTACACCAGCCCTTCTTC |

| VF-vasK-qPCR-F | ACATCCAACGCCAATACG |

| VF-vasK-qPCR-R | CAATCGCAGTGAAGACAAC |

| VF-vasH-qPCR-F | GGTAATCGGATACTGGAAC |

| VF-vasH-qPCR-R | CATGTCAACTTGCTGGAT |

| HcpA-up-Biotin | TGAGAATAGCCTTCCTTGAC |

| HcpA-dn-Biotin | GAGTTTGACCTTCGATAGAG |

| T6SS2-up-Biotin | ACCATGATCTGTTCTGGGAT |

| T6SS2-dn-Biotin | TTAGGAGCTACACTTCCTTC |

∗The underlined bases indicate the restriction enzyme sites.

Construction of Mutants and Complementation Plasmids

In-frame deletion mutants ΔihfA and ΔihfB were constructed by allelic exchange using 85003 as a precursor. Briefly, chromosomal DNAs flanking the ihfA and ihfB open reading frames (ORFs) were amplified with primer pairs listed in Table 2. The amplified upstream and downstream DNAs of the target genes were stitched together by overlapping PCR as described previously (Wu et al., 2015). The resulting 1.69 kb ΔihfA and 1.70 kb ΔihfB fragments were cloned at BamHI/XhoI sites into pWM91 suicide plasmid. The resultant recombinant plasmids, pWM-ΔihfA and pWM-ΔihfB, were mobilized into the strain 85003 from E. coli SM10λpir by conjugation. Exconjugants were selected in LB medium containing Amp and Sm and counter-selected by growing on LB agar containing 15% sucrose. Sucrose-resistant colonies were tested for Amp sensitivity, and mutant allele was verified by PCR and further confirmed by DNA sequencing. The construction procedure for vasH mutant was described previously (Huang et al., 2017).

Complementation plasmids, pSRihfA and pSRihfB, were constructed by cloning the ihfA and ihfB coding sequences into pSRKTc using NdeI/XhoI sites. The ihfA and ihfB were expressed from the lac promoter with the induction of IPTG.

Luminescence Activity Assay

Vibrio fluvialis strain containing lux reporter fusion plasmids was grown overnight with shaking, diluted 1:100 in fresh LB, and 200 μl aliquots were transferred into an opaque-wall 96-well microtiter plate (Ostar 3917). The plates were incubated at 30°C or 37°C with agitation. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) and luminescence were measured by using a microplate reader (Infinite M200 Pro, Tecan). Luminescence activity is calculated as light units/OD600 after the light units and OD600 were blank-corrected.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Vibrio fluvialis strains were grown in LB medium to OD600 1.5. Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed as described previously (Wu et al., 2015). qRT-PCR was performed by CFX96 (Bio-Rad) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Relative expression values (R) were calculated using the equation R = 2-(ΔCqtarget-ΔCqreference), where Cq is the fractional threshold cycle. The recA mRNA was used as an internal reference. A control mixture using total RNA as a template was performed for each reaction to exclude chromosomal DNA contamination. The primers used for these target genes, recA, tssD2 (hcp), tssI2 (vgrG), tssB2 (vipA), vasH, and tssM2 (vasK), were listed in Table 2.

Analyses of VflT6SS2 Expression and Secretion

Overnight cultures of V. fluvialis were diluted 1:100 in 5 mL fresh LB and incubated to OD600 of 1.5 with shaking at 30°C. In complementation assays, ΔihfA/pSRihfA or ΔihfB/pSRihfB were grown to OD600 of 0.5 with Tc. Then, each culture was divided in half. One half was induced by the addition of IPTG (final concentration of 0.5 mM), and the other half was used as a control. The cultures were continually incubated for 3 h with shaking. ΔihfA and ΔihfB containing pSRKTc were used as controls. Protein samples from cell pellets and cell-free supernatants were prepared as previously described with minor modifications (Huang et al., 2017). Trichloroacetic acid precipitated proteins from 1 ml cell-free culture supernatant were suspended in 100 μl RIPA lysis buffer (mild) (ComWin Biotech, Beijing, China). Cell pellets from 1 ml culture were suspended in 200 μl RIPA lysis buffer (mild). After 30 min incubation on ice, samples were centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C and supernatants were normalized to the amount of total protein as assayed by the BCATM protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). Western blot analysis was performed as described previously using polyclonal rabbit anti-Hcp antibody and anti-E. coli cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) antibody (BioLegend, United States) (Huang et al., 2017).

Bacterial Killing Assay

Bacterial killing assay was used to evaluate the antibacterial virulence of V. fluvialis and performed as described previously with E. coli MG1655 as the prey strain (Huang et al., 2017). V. fluvialis predator strains 85003, ΔihfA and ΔihfB were grown overnight on LB agar containing 2% NaCl (340 mM) at 30°C. For complementation strains, ΔihfA/pSRihfA and ΔihfB/pSRihfB, a 2-h extra induction with IPTG in LB was included to fully induce ihfA and ihfB expressions. The colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter of the prey E. coli at the beginning (0 h) and after 5-h incubation with predator (5 h) were determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions on Sm and Rfp resistant agar plates. Strain with control vector was used as a negative control.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The 375 bp probes for the wild-type and mutated tssD2a promoter regions were amplified with primer pair HcpA-up-Biotin/HcpA-dn-Biotin using plasmids ptssD2a-lux and ptssD2aM-lux as templates, respectively. The 450 bp probe for the VflT6SS2 major cluster promoter was amplified with primer pair T6SS2-up-Biotin/T6SS2-dn-Biotin using pVflT6SS2-lux as a template. Binding reactions were performed by mixing 20 ng biotin-labeled probe with increasing amounts of purified V. cholerae IHF heterodimers in a volume of 20 μl containing binding buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2.5 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol], 0.5 μg of calf thymus DNA, and 5 μg/ml bovine serum albumin. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and then separated on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel. The separated free probe DNA and DNA-protein complexes were transferred onto nylon membranes and visualized with the Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The above primer sequences were displayed in Table 2. The constructions of the plasmids expressing V. cholerae IHFα and IHFβ subunits and their expressions and purifications will be introduced elsewhere (Li et al., manuscript in preparation).

Results

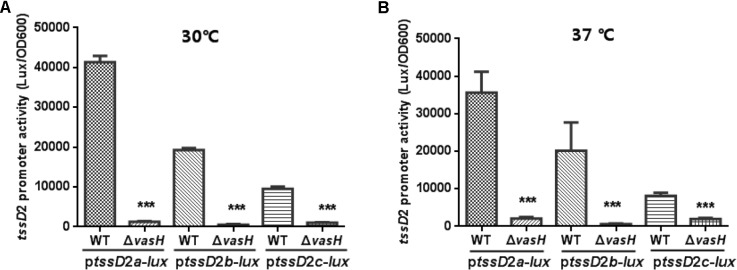

Expressions of Three tssD2-tssI2 Clusters in V. fluvialis VflT6SS2

Our previous study showed that V. fluvialis VflT6SS2 contains three tssD2-tssI2 alleles on different chromosomal locations which are involved in interbacterial competition and the anti-bacterial activity requires transcriptional regulator VasH (Huang et al., 2017). To further dissect the expression and contribution of each allele, we constructed ptssD2a-lux, ptssD2b-lux, and ptssD2c-lux reporter plasmids and introduced them into WT and isogeneic ΔvasH mutant and measured the heterogeneous promoter-driven luminance activity at 30°C culture conditions. As shown in Figure 1A, in the WT, ptssD2c-lux has the lowest promoter activity which is only one fourth of that of ptssD2a-lux, the one with the highest activity. The activity of ptssD2b-lux falls in between. In the vasH deletion background, the promoter activities of the three alleles are all very low compared to the WT. These results are consistent with our previous tssD2 mutations’ phenotypes (Huang et al., 2017) and provide a possible explanation why expression of tssD2_c alone cannot maintain the function of VflT6SS2 in terms of Hcp secretion and interbacterial virulence. Our results also show that although three tssD2-tssI2 alleles in V. fluvialis have differential expression profiles, they are all positively regulated by VasH as in V. cholerae (Dong and Mekalanos, 2012).

FIGURE 1.

Promoter activities of ptssD2a-lux, ptssD2b-lux and ptssD2c-lux under different culture temperatures. Overnight cultures of the V. fluvialis strains 85003 (WT) or ΔvasH containing either ptssD2a-lux, ptssD2b-lux, or ptssD2c-lux reporter fusions were diluted 1:100 in LB medium and 200 μl aliquots were transferred to Opaque-wall 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated at 30°C (A) or 37°C (B) with shaking for measuring the OD600 and light units. Luminescence activity is calculated as light units/OD600. The data represent three independent experiments. ∗∗∗Significantly different between WT and ΔvasH mutant (t-test, P < 0.001).

The VflT6SS2 was previously shown to be unfunctional at 37°C with extremely low tssD2 mRNA levels (Huang et al., 2017), so we wondered whether this is due to very low transcription of the three tssD2 alleles under this temperature. So we measured the promoter activities of ptssD2a-lux, ptssD2b-lux, and ptssD2c-lux at 37°C culture condition. Beyond our expectation, the transcription levels of ptssD2a-lux, ptssD2b-lux, and ptssD2c-lux at 37°C are nearly comparable to that at 30°C (Figure 1B), suggesting a post-transcriptional regulation is probably involved in the rapid degradation of hcp (tssD2) transcripts.

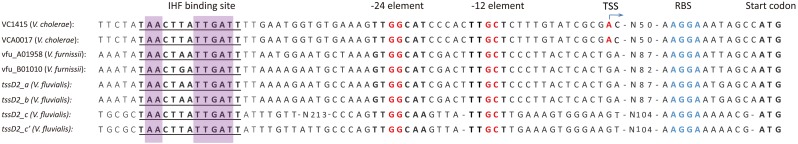

Bioinformatics Analysis of the Promoter Regions of the Three tssD2-tssI2 Clusters in V. fluvialis

To gain insight into the regulation of tssD2-tssI2 alleles, we first inspected the sequence features of the promoter regions of tssD2_a, tssD2_b and tssD2_c. σ54 (-12/-24) consensus sequences and putative IHF binding site were predicted in all three alleles’ promoters (Figure 2). The presence of σ54 consensus sequences indicates the dependence of Eσ54 for the transcription of the tssD2 clusters, which is in agreement with the requirement of VasH for the promoter activities (Figure 1). VasH functions as a specialized activator which binds to σ54 and induces conformational rearrangement in the Eσ54 closed complex (Kitaoka et al., 2011). In addition, a 13-bp asymmetric consensus sequence TAACTTATTGATT within the three promoters was identified which excellently matches with E. coli IHF consensus sequence YAANNNNTTGATW, where Y stands for T or C, N for any base, and W for A or T (Craig and Nash, 1984). Moreover, the σ54 consensus sequences and IHF binding sites show similar sequence intervals among hcp homologs from V. cholerae, Vibrio furnissii, and V. fluvialis except for the tssD2_c which shows a 225-bp instead of 16-bp interval (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Characteristics of the promoters of hcp homologs among different Vibrio species. The hcp promoter sequences from V. cholerae, V. furnissii, and V. fluvialis were compared which share highly sequence homology in T6SS. The IHF binding sites are underlined, and the conserved bases in E. coli are indicated with purple background. The potential ribosome binding sites (RBS) are labeled with blue bases. The –24 and –12 elements of σ54 binding sites are marked with red bases. The transcriptional start sites (TSSs) of VC1415 (hcp-1) and VCA0017 (hcp-2) are designated with an arrow according to that reported in a serotype O17 V. cholerae strain (Williams et al., 1996).

Considering that the promoter of tssD2_c displayed the lowest transcription activity in WT compared to those of tssD2_a and tssD2_b (Figure 1), we wondered whether the 225-bp interval is responsible for its reduced transcription. To test this possibility, we constructed a new reporter fusion, ptssD2c′-lux, which contains a modified tssD2_c promoter with only 16-bp space between the IHF binding site and the σ54 motif (Figure 2). However, the ptssD2c′-lux produced more than sixfold less luminance activity than its WT (data not shown), indicating that the 225-bp sequence likely contains unknown cis-acting element(s) essential for its promoter activity and the long sequence spacing is probably not of the reason for the low transcriptional activity of ptssD2c-lux. The underlying mechanism remains to be investigated.

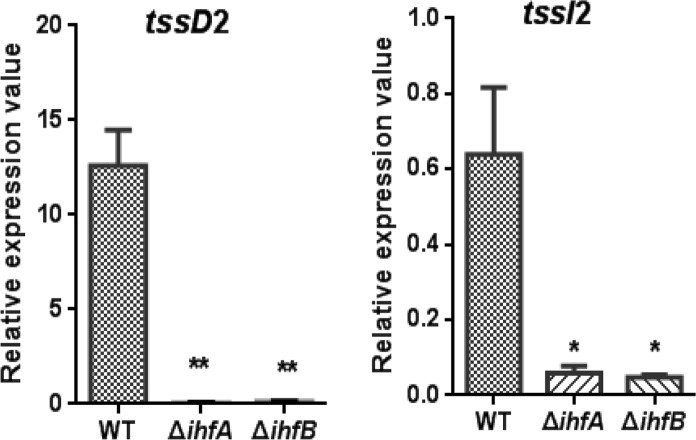

IHF Positively Regulates V. fluvialis VflT6SS2

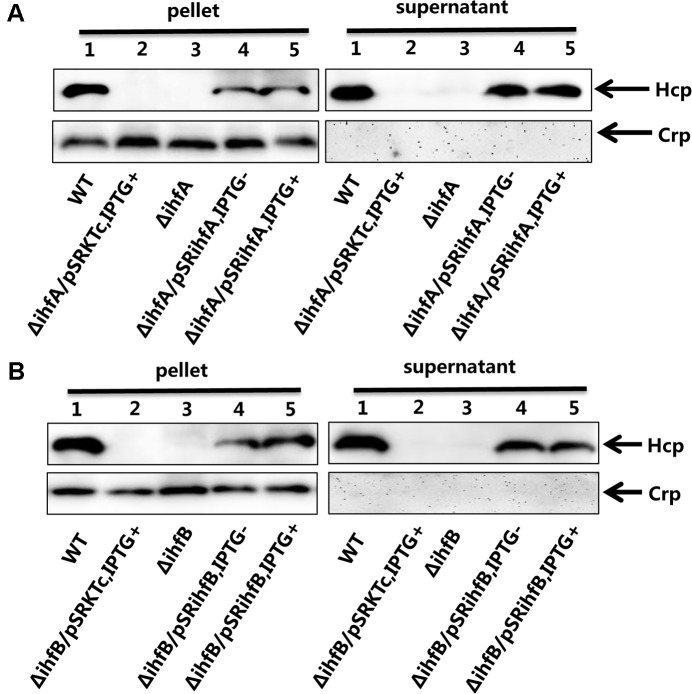

The IHF is a heterodimeric protein consisting of two subunits, IHFα and IHFβ, encoded by the ihfA and ihfB genes, respectively. The IHFα (11.0 kDa) and IHFβ (10.8 kDa) subunits in V. fluvialis have 45% sequence identity to each other. To assess the regulatory role of IHF on VflT6SS2, we generated ΔihfA and ΔihfB mutants based on strain 85003. We first compared the mRNA levels of tssD2 and tssI2 between the WT and the ihf mutants. As shown in Figure 3, the mRNA levels of tssD2 and tssI2 are significantly reduced in ΔihfA and ΔihfB mutants relative to their WT. Consistently, the expression and secretion of Hcp are completely abolished in these mutants (Figures 4A,B, lanes 3), indicating that IHF plays a role in the positive regulation of VflT6SS2. Furthermore, introduction of a complemented plasmid pSRihfA or pSRihfB into corresponding ΔihfA or ΔihfB mutant restored Hcp expression and secretion while introduction of their control vector pSRKTc failed to do so (Figures 4A,B, compare lane 2 to lanes 4 and 5). Recovery of Hcp production even occurred in conditions without IPTG induction (Figures 4A,B, compare lane 4 to lane 5). These results suggested that IHF is required for expression of hcp. The identical phenotypes of the ΔihfA and ΔihfB mutants also imply that IHFα and IHFβ form a complex to modulate Hcp expression in V. fluvialis, though differential effects on transcription by deletion of ihfA or ihfB were reported during culture in rich LB medium (Mangan et al., 2006).

FIGURE 3.

qRT-PCR analysis of the mRNA abundance of hcp-vgrG orphan clusters in V. fluvialis WT and IHF deletion mutant. V. fluvialis 85003 (WT), ΔihfA, or ΔihfB mutant was grown at 30°C in LB medium to around OD600 1.5. RNA was extracted, and the mRNA abundances of tssD2 (hcp) and tssI2 (vgrG) were determined by qRT-PCR as described in the Section “Materials and Methods.” The data represent three independent cultures. ∗∗Significantly different from WT (t-test, P < 0.01). ∗Significantly different from WT (t-test, P < 0.05).

FIGURE 4.

Influence of IHF on the VflT6SS2 Hcp expression and secretion. (A) V. fluvialis 85003 (WT), ΔihfA mutant, ΔihfA with the empty vector pSRKTc, or with IHFα expression vector pSRihfA. (B) V. fluvialis 85003 (WT), ΔihfB mutant, ΔihfB with the empty vector pSRKTc, or with IHFβ expression vector pSRihfB. Strains were grown at 30°C in LB medium to around OD600 1.5. Western blot analysis with the anti-Hcp or anti-CRP antibody was performed with 7 μg of total protein extract from the cell pellets and culture supernatants. Lane 1, WT; Lane 2, ΔihfA or ΔihfB with the empty vector pSRKTc with IPTG induction; Lane 3, ΔihfA or ΔihfB; Lane 4, ΔihfA or ΔihfB with corresponding expression vector pSRihfA or pSRihfB without IPTG induction; Lane 5, ΔihfA or ΔihfB with corresponding expression vector pSRihfA or pSRihfB with IPTG induction. The arrows show the immunoblot band to Hcp or Crp. The Crp protein is absent in the culture supernatants, indicating the detection of Hcp in the supernatants was not a consequence of cell lysis.

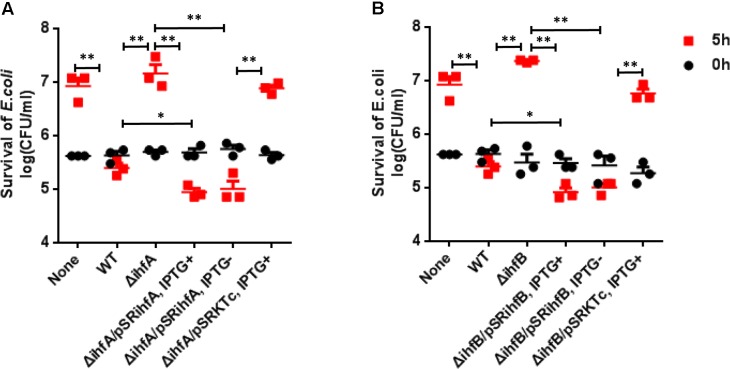

Previously we have shown that VflT6SS2 plays a role in interbacterial virulence of V. fluvialis (Huang et al., 2017). Since IHF regulates the expression of VflT6SS2, we speculate that IHF modulates interbacterial competition through targeting VflT6SS2. Therefore, we performed bacterial killing assay by employing E. coli MG1655 as a prey. Our results showed that the colony-forming ability of the E. coli prey was retained when co-cultured with ΔihfA (Figure 5A) or ΔihfB (Figure 5B) mutants, but not with its WT. However, this ability was compromised when incubated with trans-complemented strains ΔihfA/pSRihfA and ΔihfB/pSRihfB, regardless of whether ihfA or ihfB was induced by IPTG or not (Figures 5A,B). Strains ΔihfA/pSRKTc and ΔihfB/pSRKTc induced with IPTG were used as controls and showed similar phenotypes to ΔihfA and ΔihfB mutants. Furthermore, under induced condition, the survival of MG1655 incubated with ΔihfA/pSRihfA or ΔihfB/pSRihfB was even lower than that incubated with its WT, which possesses only one copy of ihfA and ihfB on the chromosome. All together, these results indicate that IHF contributes to the competitive fitness of V. fluvialis through activating the VflT6SS2-mediated bactericidal activity.

FIGURE 5.

Influence of IHF on the VflT6SS2-dependent competition between V. fluvialis and E. coli strain MG1655. (A) V. fluvialis 85003 (WT), ΔihfA mutant, ΔihfA with expression vector pSRihfA or with the empty vector pSRKTc. (B) V. fluvialis 85003 (WT), ΔihfB mutant, ΔihfB with expression vector pSRihfB or with the empty vector pSRKTc. Bacterial killing assay was performed as described in the Section “Materials and Methods.” The CFU of the prey E. coli strain MG1655 was determined at the start point (0 h) and after 5-h (5 h) co-culture with V. fluvialis predator at 30°C on LB agar containing 2% NaCl (340 mM). The data represent three independent experiments. None = medium only. WT = wild-type. ∗∗Significant differences between sample groups at 5 h (t-test, P < 0.01). ∗Significant differences between sample groups at 5 h (t-test, P < 0.05).

IHF Transcriptionally Activates the Expression of tssD2-tssI2

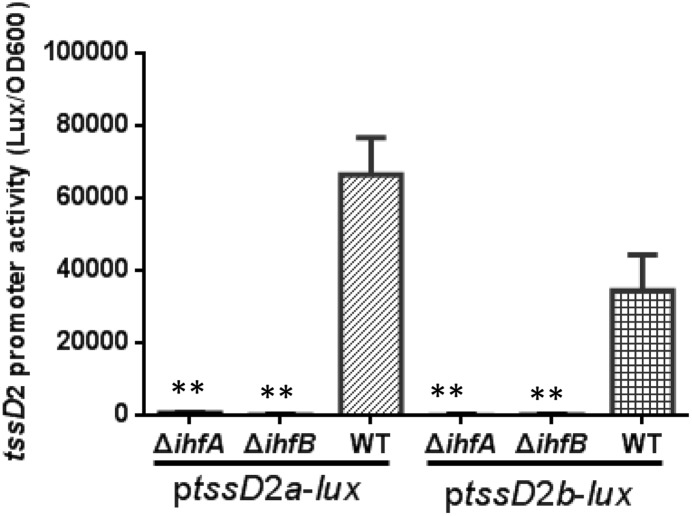

The IHF is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein, and its regulatory function relies on its ability to bend the DNA to which it binds (Robertson and Nash, 1988; Stonehouse et al., 2008; Prieto et al., 2012). The presence of IHF binding sites on tssD2 promoters implies a direct transcriptional regulation by IHF. Since tssD2_a and tssD2_b are two highly expressed alleles, we focused on these two. First, we introduced the ptssD2a-lux or ptssD2b-lux reporter fusion into WT, ΔihfA, or ΔihfB mutant, and their promoter activities were measured. As shown in Figure 6, the luminescence activities of ptssD2a-lux or ptssD2b-lux in ΔihfA and ΔihfB mutants were almost undetectable compared to those in WT, indicating that the promoters of tssD2_a and tssD2_b cannot initiate transcription without expression of IHF.

FIGURE 6.

Influence of IHF on tssD2a-lux and tssD2b-lux expression. Overnight cultures of the V. fluvialis strains 85003 (WT), ΔihfA or ΔihfB each containing either ptssD2a-lux or ptssD2b-lux reporter fusions were diluted 1:100 in LB medium and 200 μl aliquots were transferred to Opaque-wall 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated at 30°C with shaking for measuring the OD600 and light units. Luminescence activity is calculated as light units/OD600. The data represent three independent experiments. ∗∗Significantly different from the WT (t-test, P < 0.05).

To further demonstrate that IHF relies on the predicted binding site and induces the transcription of tssD2, we set out to introduce mutations in the IHF binding site in its promoter region. As the predicted IHF binding sites in tssD2_a and tssD2_b are identical (Figure 2), we selected tssD2_a as a representative. We first introduced 4-bp changes in the most highly conserved IHF binding sites by replacing the first A and the TGA with C and ACC, respectively, and named this construct as ptssD2aM-lux(Figure 7A). In V. cholerae, these mutations have been demonstrated to abolish the binding of IHF to tcpA promoter (Stonehouse et al., 2008). Therefore, we compared the promoter activity between ptssD2a-lux and ptssD2aM-lux in WT and ΔihfA mutant. As depicted in Figure 7B, the luminescence activity of the ptssD2aM-lux was sixfold less than that of ptssD2a-lux in WT background, but no significant difference was observed in ΔihfA mutant (Figure 7B), suggesting that the predicted IHF binding site is required for its effect on transactivation of tssD2.

FIGURE 7.

Influence of IHF consensus site mutations on tssD2a promoter activity and IHF binding. (A) The ptssD2aM-lux was constructed by introducing 4-bp changes in the IHF consensus site at the tssD2a promoter region. (B) Overnight cultures of V. fluvialis WT and ΔihfA strains containing either ptssD2a-lux or ptssD2aM-lux reporter fusions were diluted 1:100 in LB medium and 200 μl aliquots were transferred to Opaque-wall 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated at 30°C with shaking for measuring the OD600 and light units. Luminescence activity is calculated as light units/OD600. The data represent three independent experiments. ∗∗Significantly different between the ptssD2a-lux and the ptssD2aM-lux reporter fusions (t-test, P < 0.01). (C) EMSAs for IHF binding to wild-type tssD2_a promoter (left, probe-tssD2a) or to its mutations (right, probe-tssD2aM). Assays were performed as described in the Section “Materials and Methods.” The biotin-labeled 375-bp DNA probes (20 ng) was incubated with increasing amounts of purified V. cholerae IHF protein. The arrow on the left side indicates the unbound free probe, whereas the arrow on the right side indicates the probe bound to IHF protein.

The EMSAs were used to assess whether IHF directly binds to tssD2_a promoter region. Due to high sequence identity of IHF between V. cholerae and V. fluvialis (92% for IHFα, 95% for IHFβ), we used purified V. cholerae IHF protein in the EMSAs. Increasing amounts of V. cholerae IHF were incubated with 20 ng of tssD2_a native or mutation-possessing promoter fragments. As shown in Figure 7C, IHF did bind tssD2_a native promoter. The intensities of the retarded-bands increased in an IHF protein dose-dependent manner and the wild-type promoter fragment was completely shifted in the presence of 590 nM IHF, while the fragment containing the IHF binding mutations failed to efficiently bind IHF. Together, our current findings supported a direct binding of IHF on tssD2_a promoter.

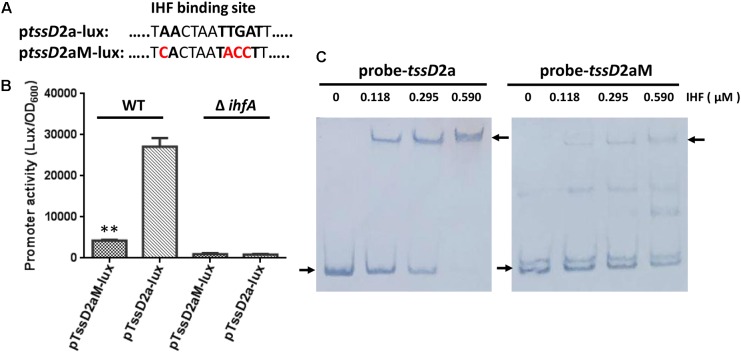

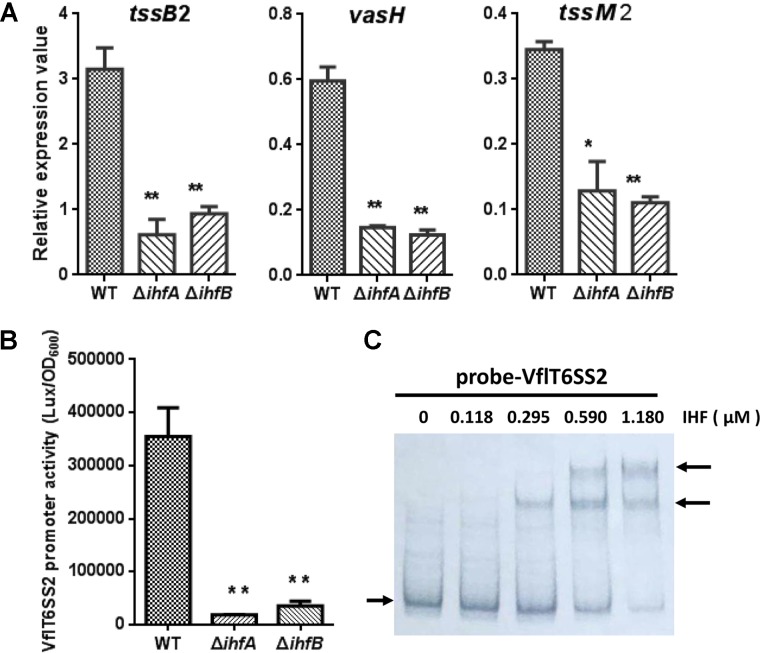

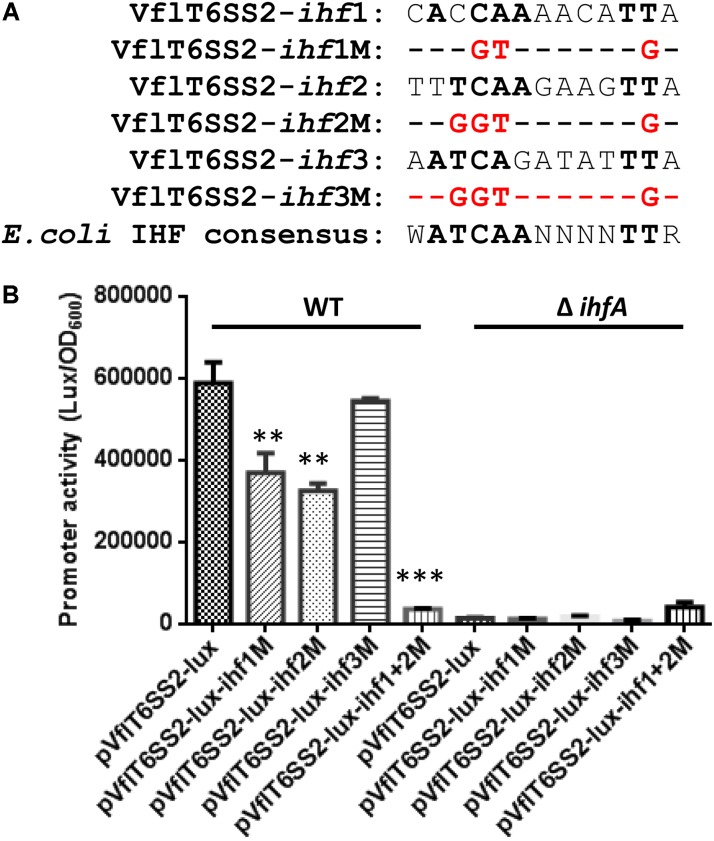

IHF Regulates the Major Cluster of VflT6SS2

The T6SS major cluster and hcp-vgrG orphan cluster could be co-regulated or separately controlled by specific regulators. In V. cholerae, VasH was shown to regulate two hcp operons but not T6SS core cluster (Dong and Mekalanos, 2012). We wondered whether the major cluster of VflT6SS2 is also regulated by IHF. Firstly we scanned the upstream intergenic sequence of tssB2 (vipA), the first gene of the major cluster, for the putative IHF binding site(s) using the software virtual footprint1. This analysis returned three medium-scoring binding sites of IHF. The first putative IHF binding sequence (5′-CACCAAAACATTA-3′) is located at nucleotides -297 to -281 relative to tssB2 start codon. The second (5′-TTTCAAGAAGTTA-3′) and the third (5′-AATCAGATATTTA-3′) lie at nucleotides -139 to -124 and -111 to -90, respectively. Generally, these sites are less-conserved and each of them has one mismatch from the E. coli IHF consensus sequence (5′-WATCAANNNNTTR-3′, where W = A or T, N = any base, and R = A or G) at different positions (Craig and Nash, 1984). To determine the actual effect of IHF on the transcription of the major cluster of VflT6SS2, we measured the mRNA levels of three selected genes (tssB2, vasH, and tssM2) within the major cluster in WT and IHF deletion mutants. As shown in Figure 8A, the abundances of tssB2, vasH, and tssM2 were significantly decreased in ΔihfA and ΔihfB mutants compared to its WT. Then, we constructed the VflT6SS2 major cluster promoter transcriptional fusion, namely pVflT6SS2-lux, which was introduced into the WT, ΔihfA or ΔihfB mutant. As expected, the luminescence activities of pVflT6SS2-lux were significantly lower in the ΔihfA and ΔihfB mutants compared to the WT, indicating that IHF upregulates the promoter activity of the major cluster of VflT6SS2 to induce its expression (Figure 8B). To confirm the direct binding of IHF to the promoter region of the VflT6SS2 major cluster, we performed EMSA. As displayed in Figure 8C, IHF was capable of binding VflT6SS2 promoter and two shifted bands appeared with the increase of IHF protein content, suggesting that IHF possibly has two binding sites in the promoter region of the VflT6SS2 major cluster (Figure 8C).

FIGURE 8.

The regulation of IHF on VflT6SS2 major cluster. (A) The mRNA abundances of VflT6SS2 major cluster genes tssB2, vasH, and tssM2 in WT and IHF deletion mutants. V. fluvialis strains 85003 (WT), ΔihfA, or ΔihfB mutant was grown at 30°C in LB medium to around OD600 1.5. RNA was extracted, and the mRNA abundances of tssB2, vasH, and tssM2 were determined by qRT-PCR. The data represent three independent cultures. ∗∗Significantly different from WT (t-test, P < 0.01). ∗Significantly different from WT (t-test, P < 0.05). (B) The transcriptional activity of the VflT6SS2 major cluster promoter in V. fluvialis WT and IHF deletion mutants. Overnight cultures of V. fluvialis strains 85003 (WT), ΔihfA, or ΔihfB containing the pVflT6SS2-lux reporter plasmid were diluted 1:100 in LB medium and 200 μl aliquots were transferred to Opaque-wall 96-well microtiter plate which was incubated at 30°C with shaking for the measurement of the OD600 and light units. Luminescence activity is calculated as light units/OD600. The data represent three independent experiments. ∗∗Significantly different from WT (t-test, P < 0.01). (C) EMSA for IHF binding to the promoter of VflT6SS2 major cluster. Assay was performed as described in the Section “Materials and Methods.” The biotin-labeled 450-bp DNA probes (20 ng) was incubated with increasing amounts of purified V. cholerae IHF protein. The arrow on the left side indicates the unbound free probe, whereas the arrow on the right side indicates the probes bound with IHF protein.

To further figure out the authentic IHF binding sites among the three predicted ones in the promoter region of VflT6SS2 major cluster, we introduced mutations in each of the three predicted IHF binding sites as depicted in Figure 9A. As shown in Figure 9B, the luminescence activities of pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1M and pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf2M were apparently decreased compared to its wild-type pVflT6SS2-lux but that of pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf3M did not. These results indicate that IHF might bind to the first and second predicted sites to regulate the expression of VflT6SS2 major cluster. To further confirm these results, we introduced mutations in both of the ihf1 and ihf2 sites. As shown in Figure 9B, the joint mutations of the two sites almost completely abolished the promoter activity of pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1+2M. This result confirms that IHF mostly binds to the ihf1 and ihf2 sites in the promoter of VflT6SS2 major cluster to modulate its expression.

FIGURE 9.

Contributions of the three putative IHF binding sites to the promoter activity of VflT6SS2 major cluster. (A) The sequences of the three predicted IHF binding sites within the promoter region of VflT6SS2 major cluster and the mutations that we incorporated into each binding site. The nucleotides identical to the E. coli consensus site are in bold. (B) Overnight cultures of V. fluvialis WT and ΔihfA strains containing either pVflT6SS2-lux, pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1M, pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf2M, pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf3M, or pVflT6SS2-lux-ihf1+2M reporter fusions were diluted 1:100 in LB medium and 200 μl aliquots were transferred to Opaque-wall 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated at 30°C with shaking for measuring the OD600 and light units. Luminescence activity is calculated as light units/OD600. The data represent three independent experiments. ∗∗Significantly different from pVflT6SS2-lux (t-test, P < 0.05). ∗∗∗Significantly different from pVflT6SS2-lux (t-test, P < 0.01).

In addition, we checked the sequence conservation of ihf1 and ihf2 sites at the T6SS major cluster promoters among different Vibrio species which share similar T6SS genetic organization. Exactly the same ihf1 and ihf2 binding sites as in the V. fluvialis 85003 were found in another V. fluvialis strain ATCC33809 isolated from Bangladesh. In V. furnissii, a genetically closest species to V. fluvialis among Vibrionaceae (Lu et al., 2014), an identical sequence to V. fluvialis ihf2 binding site is present. While in V. cholerae, no such putative binding sites were identified at the promoter region of T6SS core cluster. These results suggest that the IHF-dependent regulation of the major T6SS cluster may vary in different Vibrio species.

Discussion

The IHF has been implicated in the regulation of over 100 genes with various functions in E. coli (Arfin et al., 2000) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Mangan et al., 2006). Furthermore, IHF has increasingly been identified as a regulator of virulence gene expression. IHF activates expression of virulence genes virF, virB, and icsA in Shigella flexneri, and two main virulence factors tcpA and ctx in V. cholerae (Porter and Dorman, 1997; Stonehouse et al., 2008). IHF is involved in transcriptional regulation of Brucella abortus virB operon, which encodes the type IV secretion system (T4SS) (Sieira et al., 2004). In this study, we provide evidences to support that IHF activates the expression of VflT6SS2 and thus antibacterial virulence in V. fluvialis by co-regulation of its major cluster and three orphan clusters.

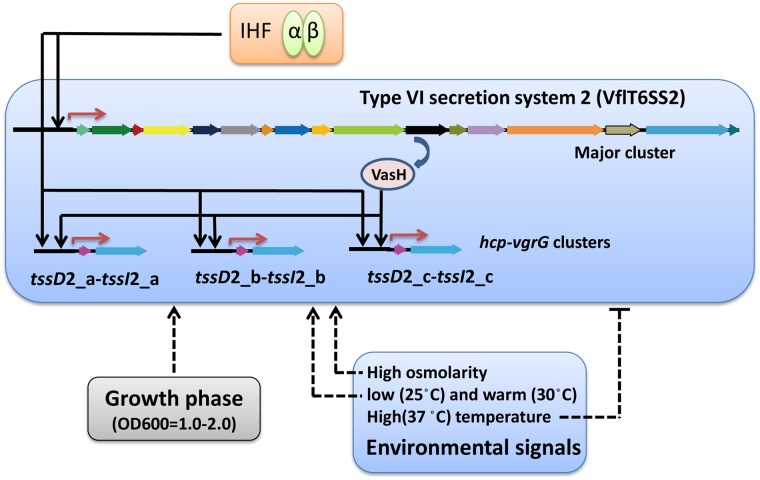

Bioinformatics analysis revealed the presence of putative IHF binding sites at the promoter regions of the three hcp-vgrG orphan clusters and the major cluster in V. fluvialis VflT6SS2. Deletion of either ihfA or ihfB resulted in a significant reduction in the expression of both the orphan and the major clusters, suggesting their co-regulation by IHF. Reporter fusion studies, EMSAs and site-directed mutagenesis jointly demonstrated the direct binding and positive transcriptional activation of VflT6SS2 by IHF. Bacterial killing assay clearly showed that lack of IHF impaired the antibacterial virulence of V. fluvialis against prey strain E. coli, while overexpression of IHF from trans-complemented plasmid not only restored, but also increased the killing activity of V. fluvialis predators to a significantly higher level than its WT (Figure 5). The co-regulatory mode of the major and orphan clusters by IHF denotes that IHF likely plays a critical role in the control of VflT6SS2 in V. fluvialis, where it firstly activates the expression of the major cluster encoding VasH and other structural components, and then together with VasH, it synergistically activates the expression of hcp-vgrG orphan clusters whose products serve both as the T6SS structural components and effector proteins. In other words, the hcp-vgrG orphan clusters are under dual control by the global regulator IHF and T6SS specific regulator VasH.

However, it seems that co-regulation of the T6SS major cluster and hcp-vgrG orphan cluster is not a common feature in Vibrio species. The regulation of IHF on hcp-vgrG orphan clusters seems more conservative than its regulation on major clusters. The promoters of hcp homologues in V. cholerae, V. furnissii and V. fluvialis all contain IHF binding sites which are highly conserved in the locations and sequence compositions (12 bp is identical out of 13-bp binding sequence, Figure 2), but the IHF binding sites at the promoters of major clusters show much variation in terms of the number of binding sites and the sequence compositions. EMSA and consensus site mutation analysis (Figures 8C, 9) demonstrated that there are two functional IHF binding sites in the VflT6SS2 major cluster promoter, while sequence comparison analysis revealed lack of or only one less conserved binding site in the corresponding major cluster promoters in V. cholerae and V. furnissii. So, unlike in the halophilic species, including V. fluvialis and V. furnissii, IHF may only specifically regulate the hcp-vgrG orphan clusters but not T6SS major cluster in the V. cholerae. The different regulation mode among different species may reflect or correlate with the distinct survival niches of the species and is worthy of being investigated later.

In addition, our results clearly showed that the three tssD2-tssI2 orphan clusters of VflT6SS2 display differential expression patterns (Figure 1). Combined with our previous data about tssD2 mutants (Huang et al., 2017), the results suggest that a moderate hcp expression (no less than the level of tssD2_b expression) is probably required to keep the function of VflT6SS2 in terms of the Hcp effector secretion and antibacterial virulence activity, and a lower expression (such as similar to tssD2_c) cannot maintain the function of VflT6SS2 under general growth conditions. Currently, the mechanism behind the differential expression is still unclear. The promoter sequences of tssD2_a-tssI2_a and tssD2_b-tssI2_b are highly homology from -228 to -1 bp (98.25% identity) relative to the start codon of the tssD2 ORFs, however, low sequence homology exists between -335 and -229 bp, which might be one reason for the differential transcription of tssD2_a and tssD2_b through affecting the binding of VasH activator. Sequence alignment analysis of T6SS-associated bacterial enhancer binding proteins (bEBPs) suggests that VasH probably responds to different signals and binds to different DNA sequences (Bernard et al., 2011). However, this hypothesis remains to be examined. VasH has been shown to bind to the promoter region of the hcp-vgrG orphan cluster in V. cholerae, but its specific binding sequences are not yet determined (Bernard et al., 2011). We do not know whether the two hcp-vgrG clusters in V. cholerae T6SS were differently expressed as in the V. fluvialis, but great sequence divergence does exist in the two hcp promoter regions starting from -193 bp relative to the start codon of the ORFs.

The tssD2_c-tssI2_c cluster is closely neighbored by three predicted phage integrases on the chromosome, suggesting a possibility of extraneous acquisition. The promoter of tssD2_c-tssI2_c cluster is highly heterologous to those of tssD2_a-tssI2_a and tssD2_b-tssI2_b, with a 225-bp-long sequence interval between the IHF and σ54 binding sites rather than a 16-bp interval found in the other two clusters. IHF was found to be necessary for the activation of transcription of some σ54 promoters where it acted to assist distant, DNA-bound transcriptional regulators or enhancer-like elements for the initiation of transcription (Freundlich et al., 1992; Engelhorn and Geiselmann, 1998). So, we originally inferred that the long sequence interval between the IHF and σ54 binding sites in tssD2_c promoter may somehow account for its low transcriptional activity, but experimental analysis of tssD2_c promoter with artificially shortened interval revealed that the interval sequence is not the reason, instead, it contains a probable cis-acting element required for maintaining its basal transcriptional activity.

The physiological significance of containing multiple copies of hcp-vgrG genes in T6SS system in V. fluvialis, as seen in other bacteria, is still unclear, and the same question for their differential expressions. To some extent, this may represent an alternative regulatory mechanism which selectively expresses hcp-vgrG pairs at certain conditions, allowing the bacteria to produce distinct Hcp/VgrG structures or forming different cocktails of Hcp/VgrG structures (Bernard et al., 2011). Hcp is not only the structural component forming 600-nm-long homohexameric inter tube through which the toxin effectors was loaded and secreted (Journet and Cascales, 2016), but also serves as an important chaperone for T6SS effectors by being secreted together with them to prevent their degradation (Silverman et al., 2013). We speculate that the chaperone function of Hcp may be benefited from the multicopy and colocation with effector VgrGs within the different clusters.

Taken together, we demonstrated here that functional expression of VflT6SS2 in V. fluvialis was positively regulated by the global regulator IHF. Current results add new information to the highly complex regulatory circuitry controlling the expression of T6SS and further broaden our knowledge of T6SS regulation. In Figure 10, we propose a model for the expression and regulation of VflT6SS2 in V. fluvialis, including transcriptional regulators and environmental signals. Specifically, IHF positively co-regulates the VflT6SS2 major cluster and hcp-vgrG orphan clusters, and the orphan clusters undergo dual regulation of IHF and VasH. Environmental conditions, such as growth stage at OD600 1.0-2.0, high osmolality, and low (25°C) or warm (30°C) temperature facilitate while high temperature (37°C) represses VflT6SS2 expression.

FIGURE 10.

Schematic representation of the regulation of V. fluvialis VflT6SS2. Activation is designated by arrow-headed lines while inhibition is indicated by bar-headed lines. Solid lines in the VflT6SS2 bubble represent the direct binding to the promoter by the regulators. Dashed lines that do not enter the VflT6SS2 bubble represent regulation through unknown mechanisms. Red arrows denote transcriptional start sites.

Author Contributions

WL and BK conceived and designed the experiments. JP, MZ, YH, and XL performed the experiments. WL, JP, JL, and ZR analyzed the data and discussed the results. WL and JP wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- ΔihfA

isogenic ihfA mutant

- ΔihfB

isogenic ihfB mutant

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- Hcp

hemolysin-coregulated protein

- IHF

integration host factor

- LB

Luria-Bertani broth

- OD600

optical density at 600 nm

- ORF

open reading frame

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- T6SS

type VI secretion system

- WT

wild-type

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFC1601503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81772242), and the National Science and Technology Major Project (2018ZX10713003-002-009).

References

- Alteri C. J., Mobley H. L. (2016). The versatile type VI secretion system. 4:VMBF-0026-2015. 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0026-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfin S. M., Long A. D., Ito E. T., Tolleri L., Riehle M. M., Paegle E. S., et al. (2000). Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12. The effects of integration host factor. 275 29672–29684. 10.1074/jbc.M002247200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M., Pilhofer M., Henderson G. P., Jensen G. J., Mekalanos J. J. (2012). Type VI secretion requires a dynamic contractile phage tail-like structure. 483 182–186. 10.1038/nature10846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C. S., Brunet Y. R., Gavioli M., Lloubes R., Cascales E. (2011). Regulation of type VI secretion gene clusters by sigma54 and cognate enhancer binding proteins. 193 2158–2167. 10.1128/JB.00029-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer F., Fichant G., Berthod J., Vandenbrouck Y., Attree I. (2009). Dissecting the bacterial type VI secretion system by a genome wide in silico analysis: what can be learned from available microbial genomic resources? 10:104. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet Y. R., Bernard C. S., Gavioli M., Lloubes R., Cascales E. (2011). An epigenetic switch involving overlapping fur and DNA methylation optimizes expression of a type VI secretion gene cluster. 7:e1002205. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Sivaraman J., Leung K. Y., Mok Y. K. (2011). Two-component PhoB-PhoR regulatory system and ferric uptake regulator sense phosphate and iron to control virulence genes in type III and VI secretion systems of Edwardsiella tarda. 286 39417–39430. 10.1074/jbc.M111.295188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig N. L., Nash H. A. (1984). E. coli integration host factor binds to specific sites in DNA. 39(3 Pt 2), 707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong T. G., Mekalanos J. J. (2012). Characterization of the RpoN regulon reveals differential regulation of T6SS and new flagellar operons in Vibrio cholerae O37 strain V52. 40 7766–7775. 10.1093/nar/gks567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhorn M., Geiselmann J. (1998). Maximal transcriptional activation by the IHF protein of Escherichia coli depends on optimal DNA bending by the activator. 30 431–441. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filloux A., Hachani A., Bleves S. (2008). The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. 154(Pt 6), 1570–1583. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016840-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freundlich M., Ramani N., Mathew E., Sirko A., Tsui P. (1992). The role of integration host factor in gene expression in Escherichia coli. 6 2557–2563. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueguen E., Durand E., Zhang X. Y., d’Amalric Q., Journet L., Cascales E. (2013). Expression of a Yersinia pseudotuberculosis type VI secretion system is responsive to envelope stresses through the OmpR transcriptional activator. 8:e66615. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho B. T., Dong T. G., Mekalanos J. J. (2014). A view to a kill: the bacterial type VI secretion system. 15 9–21. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Du P., Zhao M., Liu W., Du Y., Diao B., et al. (2017). Functional characterization and conditional regulation of the type VI secretion system in Vibrio fluvialis. 8:528. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T., Sabharwal D., Broms J., Milton D. L., Sjostedt A., Uhlin B. E., et al. (2012). Pathoadaptive conditional regulation of the type VI secretion system in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains. 80 575–584. 10.1128/IAI.05510-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A., Kostiuk B., Rogers A., Teschler J., Pukatzki S., Yildiz F. H. (2017). Rules of engagement: the type VI secretion system in Vibrio cholerae. 25 267–279. 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journet L., Cascales E. (2016). The type VI secretion system in Escherichia coli and related species. 7 1–20. 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0009-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S. R., Gaines J., Roop R. M., II, Farrand S. K. (2008). Broad-host-range expression vectors with tightly regulated promoters and their use to examine the influence of TraR and TraM expression on Ti plasmid quorum sensing. 74 5053–5062. 10.1128/AEM.01098-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka M., Miyata S. T., Brooks T. M., Unterweger D., Pukatzki S. (2011). VasH is a transcriptional regulator of the type VI secretion system functional in endemic and pandemic Vibrio cholerae. 193 6471–6482. 10.1128/JB.05414-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoux M., Kirkpatrick R. L., Montauti E. I., Tran B. Q., Peterson S. B., Harding B. N., et al. (2015). Kin cell lysis is a danger signal that activates antibacterial pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. 4:e05701. 10.7554/eLife.05701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Liang W., Wang Y., Xu J., Zhu J., Kan B. (2014). Identification of genetic bases of Vibrio fluvialis species-specific biochemical pathways and potential virulence factors by comparative genomic analysis. 80 2029–2037. 10.1128/AEM.03588-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan M. W., Lucchini S., Danino V., Croinin T. O., Hinton J. C., Dorman C. J. (2006). The integration host factor (IHF) integrates stationary-phase and virulence gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. 59 1831–1847. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougous J. D., Gifford C. A., Ramsdell T. L., Mekalanos J. J. (2007). Threonine phosphorylation post-translationally regulates protein secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. 9 797–803. 10.1038/ncb1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M. E., Dorman C. J. (1997). Positive regulation of Shigella flexneri virulence genes by integration host factor. 179 6537–6550. 10.1128/jb.179.21.6537-6550.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto A. I., Kahramanoglou C., Ali R. M., Fraser G. M., Seshasayee A. S., Luscombe N. M. (2012). Genomic analysis of DNA binding and gene regulation by homologous nucleoid-associated proteins IHF and HU in Escherichia coli K12. 40 3524–3537. 10.1093/nar/gkr1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukatzki S., Ma A. T., Revel A. T., Sturtevant D., Mekalanos J. J. (2007). Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. 104 15508–15513. 10.1073/pnas.0706532104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukatzki S., Ma A. T., Sturtevant D., Krastins B., Sarracino D., Nelson W. C., et al. (2006). Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. 103 1528–1533. 10.1073/pnas.0510322103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson C. A., Nash H. A. (1988). Bending of the bacteriophage lambda attachment site by Escherichia coli integration host factor. 263 3554–3557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A. B., Wexler A. G., Harding B. N., Whitney J. C., Bohn A. J., Goo Y. A., et al. (2014). A type VI secretion-related pathway in Bacteroidetes mediates interbacterial antagonism. 16 227–236. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon D., Gonzalez H., Updegraff B. L., Orth K. (2013). Vibrio parahaemolyticus type VI secretion system 1 is activated in marine conditions to target bacteria, and is differentially regulated from system 2. 8:e61086. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon D., Klimko J. A., Orth K. (2014). H-NS regulates the Vibrio parahaemolyticus type VI secretion system 1. 160(Pt 9), 1867–1873. 10.1099/mic.0.080028-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y., Bassler B. L. (2014). Quorum regulatory small RNAs repress type VI secretion in Vibrio cholerae. 92 921–930. 10.1111/mmi.12599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieira R., Comerci D. J., Pietrasanta L. I., Ugalde R. A. (2004). Integration host factor is involved in transcriptional regulation of the Brucella abortus virB operon. 54 808–822. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. M., Agnello D. M., Zheng H., Andrews B. T., Li M., Catalano C. E., et al. (2013). Haemolysin coregulated protein is an exported receptor and chaperone of type VI secretion substrates. 51 584–593. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. M., Brunet Y. R., Cascales E., Mougous J. D. (2012). Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system. 66 453–472. 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonehouse E., Kovacikova G., Taylor R. K., Skorupski K. (2008). Integration host factor positively regulates virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. 190 4736–4748. 10.1128/JB.00089-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. G., Varcoe L. T., Attridge S. R., Manning P. A. (1996). Vibrio cholerae Hcp, a secreted protein coregulated with HlyA. 64 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R., Zhao M., Li J., Gao H., Kan B., Liang W. (2015). Direct regulation of the natural competence regulator gene tfoX by cyclic AMP (cAMP) and cAMP receptor protein (CRP) in Vibrios. 5:14921. 10.1038/srep14921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]