Abstract

Purpose of review

Living donor transplantation offers patients with end-stage renal disease faster access to transplant and better survival and quality of life than waiting for a deceased donor or remaining on dialysis. While many people state they would be willing to help someone in need through kidney donation, there are education and communication barriers to donor candidate identification. These barriers might be mitigated by technological innovations, including the use of social media.

Recent findings

This article describes the state of contemporary evidence regarding use of social media tools and interventions to increase access to living donor transplantation, as reported in peer-reviewed medical literature, as well as programs that have not yet been formally evaluated.

Summary

As social media platforms continue to grow and expand, a commitment to understanding and facilitating the use of social media by the transplant community may support patients who are interested in using social media as a tool to find a living kidney donor.

Keywords: Living organ donation, living donor transplantation, social media, internet, digital health

INTRODUCTION

Living organ donor transplantation provides excellent patient outcomes compared to other options for patients facing end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) offers patients with ESRD the opportunity to access a transplant faster than waiting for a deceased donor kidney, with the possibility of avoiding dialysis altogether, and superior long-term survival compared to both dialysis and deceased donor kidney transplantation. The American Society of Transplantation has promoted LDKT as the “best treatment option” for eligible patients with kidney failure [1]. There are more than 100,000 persons on the national kidney transplant waiting list, but despite the benefits of LDKT, it is the least common treatment option for patients with ESRD. Currently, 5,500 cases of LDKT are performed in the US each year compared to 13,000 cases of deceased donor kidney transplantation [2, 3]. There are widely cited barriers to LDKT including identifying a potential and willing living donor[4] [5], ensuring a healthy living donor,[6] and utilizing a healthy living donor [7–9]. One of these barriers, identifying a potential and willing living donor, often stems from a transplant candidate’s 1) reluctance to ask [4, 10], and 2) lack of knowledge about the process of living donation [4, 11]. Both of these barriers may be mitigated by technological innovations, including the use of social media.

In 2003, several online sites were launched including MySpace, Friendster, and Facebook [12]. Given the popularity and growth of these sites over the past decade, social media has now become a seamless part of everyday life, with more than 70 percent of Facebook users logging into the site daily [13]. Furthermore, a 2015 Pew Research Center report found that 52 percent of online adults adopted two or more social media sites [14]. As the term social media has many meanings and is often conceptually related to other terms including social networking sites and online social networks, it is not always clear what tools, platforms, and social phenomena are construed as social media [15]. Social media share commonalties and features across platforms, including sharing and evaluating content, means for connecting with a social network, and search and save functions [16]. While all media has been considered social, only a particular subset has been fundamentally defined by their sociality [17], thus, social media can be defined as: “web-based services that allow individuals, communities, and organizations to collaborate, connect, interact, and build community by enabling them to create, co-create, modify, share, and engage with user generated content that is easily accessible” [15].

Ten types of social media applications have been identified in an attempt to explain how each type of platform may be leveraged for specific marketing purposes and goals [18]. Social networking sites, bookmarking, social news, media sharing, microblogging, blogs and forums, collaborative authoring, conferencing, scheduling and meeting tools, and geo-location based sites (Table 1). While not all social media types and platforms have been used or examined by the transplant community for their effectiveness, patients, families, and transplant hospitals have been leveraging social media for over a decade to help with the search for a healthy and willing living donor [19]. Unlike primary traditional one-way communication channels such as billboards, radio advertisements, and television, social media is advantageous in that there is lower barrier to entry and content can quickly be spread or ‘go viral’ [20, 21]. Thus, the development of social media communities in organ transplantation for the purpose of seeking a living donor have largely grown from patient and grassroots efforts [19].

Table 1.

Types of Social Media, Examples, and Definitions

| Types of social media | Definitions | Example Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Social networking sites | ‘Web-based services that allow individuals to 1) construct a public or semi-public profile with a bounded system, 2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and 3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system.’[12] | Facebook |

| Bookmarking | ‘Provide a mix of both direct (intentional navigational advice as well as indirect (inferred) advice based on collective public behavior. By definition these social bookmarking systems provide “social filtering” on resources from the web and intranet. The act of bookmarking indicates that one is interested in a given resource. At the same time, tags provide semantic information about how the resource can be viewed.’[42] | StumbleUpon |

| Microblogging | ‘Services that focus on short updates that are pushed out to anyone subscribed to receive the updates.’[18] | Twitter Tumblr |

| Blogs and forums | ‘Online forums allow members to hold conversations by providing messages. Blog comments are similar except they are attached to blogs and usually the discussion centers around the topic of the blog post.’ [18] | WordPress Blogger |

| Media sharing (primary function) | ‘Services that allow you to upload and share various media such as pictures and video. Most services have additional features such as profiles, commenting, etc.’[18] | Instagram YouTube |

| Social news | “Services that allow people to post various news items or links to outside articles and then allows it’s users to “wove” on the items. The voting the is core social aspect as the items that get the most votes are displayed most prominently. The community decides which news item gets seen by more people.’[18] | Reddit Digg |

| Collaborative authoring | ‘Web-based services that enable users to create content and allow anyone with access to modify, edit, or review that content.’[43] | GoogleDocs Wikipedia Dropbox |

| Web-conferencing | ‘Web-conferencing may be used as an umbrella term for various types of online collaborative services including web-seminars (“webinars”), webcasts, and peer-level webmeetings[44, 15] | Skype Google Hangout |

| Scheduling and meeting | Web based services enabling group-based event decisions[45] [46] | Doodle, Microsoft Outlook |

| Geo-location based | Services that allow its users to connect and exchange messages based on their location. Most platforms have this, but some are distinctly created for this purpose. | Foursquare Tinder |

Transplant hospitals’ comfort with social media use by patients to help identify a living donor, as well as evaluation and acceptance practices for living donor candidates identified or meeting their recipient only through social media, is likely not uninform and currently unknown. However, there have also been calls within the transplant community to increase the use of publically facing interventions, such as social media, to promote living kidney donation to the general public [22]. The 2015 American Society of Transplantation consensus conference on best practices in living kidney donation identified providing patients and caregivers with training about how to identify and approach a potential living donor as a high priority action item [1]. As use of social media is an emerging area in organ transplantation, the state of contemporary evidence on social media strategies to increase access to living donor transplantation has not been reviewed. This article describes use of social media tools and interventions for living donor identification as reported in peer-reviewed medical literature, as well as programs that have not yet been formally evaluated.

REVIEW METHODOLOGY

We queried the PUBMED electronic database for reports published through August 1, 2017 using the subject headings “living donor* or “living organ donor”* or “live organ donor” or “living kidney donor” or “live kidney donor” or “kidney donor,” or “live donor kidney transplantation,” “living donation,” and “social media.” Searches were limited to articles published in English. The search term “living donor and social media” yielded the most comprehensive results (n = 24). We also searched for “living donation and mobile apps” and “living donation and mobile applications” (n =3). We then queried Google for the same search terms to identify unpublished, lay/community, and grassroots efforts at using social media to increase LDKT. This was not designed as a systematic review in which only a narrow range of studies are identified. Rather given the paucity of evidence on social media interventions to increase LDKT [23] and in general, social media in transplantation, strategies that have not been formally evaluated or that have no published data are included in this review. A detailed description of educational interventions and programs designed to increase LDKT which may have dissemination platforms on social media can be found in Hunt et al., 2017 [24]. The current review focuses on the emerging area of social media and LDKT, and specifically provides descriptions of online social networking, media strategies and platforms for transplant candidates seeking a living kidney donor.

Early Efforts: Donor-Recipient Matching Social Networking Websites

As possibly one of the earliest ways social media has been used to help transplant candidates find a living donor, donor-recipient matching websites such as MatchingDonors.com [25] have been documented since 1994 [26]. This donor-recipient matching website boasts 1.5 million website hits per month, and has become one of the most successful nonprofit organizations finding living organ donors for patients needing transplants. Now with a paired exchange program, MatchingDonors.com claims that nearly 15,000 registered potential living donors participate on their site. MatchingDonors.com requires that a user pay for posting a profile containing information about their need for a kidney. Patient memberships (organ registration fee) is based on length of membership, with plans ranging from 7 day trial memberships ($49.00), 90 days ($441.00), or even lifetime memberships ($595.00) [25].

Donor-recipient matching social networking websites like Matchingdonors.com raise ethical concerns about the reinforcement of inequities between those who can and cannot pay for services that offer enhanced or increased access to interested potential living donors [19]. Despite any ethical concerns, LDKT facilitated through donor-recipient social networking websites continue at US transplant hospitals, although there is no national data to report about the practice. It should be noted that payment to broaden the reach of a patient message about living donation is not unique to donor-recipient matching websites, considering for example, the expense for a paid billboard advertisement [27].

Facebook: The New Way to Find a Kidney Donor

Founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg while a student at Harvard University, Facebook originally was an online registry only for college students to rate each other’s attractiveness [28]. Since 2006, Facebook has been open to anyone with a valid email address, and today is the most popular social media site used by American adults daily [13]. Facebook users can post comments, share photographs and links to news or other interesting content on the Internet, play games and apps, chat live, and even stream live video. Facebook remains free to join, and makes a profit through advertising revenue. Content shared on Facebook can be made publicly accessible, or it can be shared only among a select group of friends or family, or with a single person.

Facebook has been shown to be a successful social media platform for increasing organ donation awareness and registration, even bolstering donor registration rates [29]. Now, Facebook has emerged as a platform in which patients might have the capacity to regularly drive the dissemination of information about living kidney donation to their social network [19]. As evidence to this effect, there has been one published survey of transplant candidates completed during an office visit about their Facebook use. In this study, Kazley et al. report that 51% (102/199) of transplant candidates would be willing to post information about living donation on their social network sites; Facebook was the most popular site [30].

Facebook Pages

Through Facebook Pages and Facebook Groups, making connections on the social media platform is not limited to friends [31]. Facebook Pages created by hopeful transplant candidates seeking a living donor have emerged on their own, although they were traditionally designed for authenticated brands to have a presence on the social network. Unlike a profile, Facebook Pages are visible to everyone on the Internet by default. Anyone can connect with a Facebook Page by ‘becoming a fan.’ When someone ‘likes’ a Facebook Page, they can elect to then receive updates in their News Feed and interact with the Page.

Chang et al. published a formal evaluation of Facebook Pages to help transplant recipients find a living kidney donor [32]. In this study, of the 91 Facebook Pages identified, 29 (32%) reported living donors being tested on their behalf; there was no significant difference in age between individuals who had potential living donors tested and those who did not (35.0 vs. 38.6, p = 0.6) [32]. Of the 13 Facebook users whose pages that reported receipt of a kidney transplant, three received deceased donor transplants, nine received liing donor transplants, and one page did not provide enough information to determine the donor type. Patient-created Facebook Pages that shared more of their characteristics, and those providing more information about transplantation had higher page traffic [32].

There is no published evidence about the effectiveness of lay efforts aimed at teaching transplant candidates about beginning Facebook Pages to find a living kidney donor. There are Facebook Pages like “Find a Kidney Central” which provide templates to transplant candidates for creatining their own Facebook pages. As of September 13, 2017, there were over 9,622 Facebook users interacting with the Find a Kidney Central page. The “KidneyBuzz” Facebook Page has a large following of over 66,000 Facebook users, and provides their “Find a Kidney Donor Campaign” service. This online program is aimed at increasing the opportunity that a customer will be able to reach potential living kidney donors. KidneyBuzz.com “Find a Kidney Donor Campaign” charges a monthly fee of $48. After signing up, a KidneyBuzz.com personal account manager will contact a transplant candidate to discuss their background, and forward this information to their Social Media team. The Social Media team will then develop a personal and robust biography to share the transplant candidate’s story to “effectively paint (you) as a 3-Dimensional person on Social Media”[33]. The KidneyBuzz.com Social Media Team will then include key terms and key words into the transplant candidate’s biography and will manage a strategic campaign to help improve the chances of connecting with potential living donors. Patient testimonials serve as the strongest evidence to the effectiveness of these lay efforts.

Facebook Groups

Facebook Groups allow people to connect for a common cause, issue or activity to organize, express objectives (e.g. living kidney donation), participate in group discussion, and to share related content and photos [31]. A Facebook user creating a Group can make access publicly available for anyone to join, require administrator approval for members to join, or keep membership private and by invitation only. Like Facebook Pages, new posts by a Group are included in the News Feeds of its members, and members can interact and share with one another from the group. There have been no published studies about the effectiveness of Facebook Groups for improving transplant candidate access to living kidney donation.

Notably, there are several community-based interventions led by patients themselves. For example, the Living Kidney Donors Network (LDKN) Facebook Group is aimed offering workshops and get-togethers to help transplant candidates succeed at finding a living donor. The LDKN offers workshops to hospitals and patients and provides resources on using Facebook as a way to create a “Kidney Kampaign.”

Twitter and Hashtags to Increase Organ Donation

Founded in 2006 by Jack Dorsey in San Francisco, CA, Twitter is an online news and social networking service that enables users to post and interact with messages, known as “tweets”, restricted to 140 characters [34]. Registered Twitter users can post tweets, but those who are unregistered can only read them [35]. Twitter is embedded in American culture and is now used by professional organizations, politicians, news professionals, professors, scientists, and other leaders to reach the general population. It has become a main channel of news communication, a reality underscored by the fact that 25% of authenticated Twitter users are journalists [36]. The appeal of Twitter is evident: it provides a vast, immediate audience. Currently, 24% of internet users (21% of adults) in the United States use Twitter, including 36% of internet users 18–29 years old [13]. Twitter campaigns have successfully engaged millions of users, with a single campaign in 2013 generating over 1.7 billion social impressions over a period of two weeks [37]. By providing a high-speed, low-cost link to the general population, the Twitter platform is becoming increasingly important for any industry that wishes to grow its influence.

A Twitter hashtag is a string of characters preceded by the hash (#) character; hashtags can be viewed as topical markers, an indication to the context of the tweet, or as the core idea expressed in the tweet. The primary purpose of the hashtag is to identify the subject(s) of the message. With these categories now incorporated right in the tweet, Twitter users are able filter their home-feed to just see tweets about particular subject matter. For example, if they search for “#transplantation”, only tweets whose subject is “transplantation” will appear. Often incorporated in Twitter campaigns, hashtags are included over and over again by different Twitter accounts, and the acceptance of a hashtag is captured by the (normalized) count of its appearance in a time interval [38]. Hashtags are also being used organize content from online communities of professionals and patients through chats on Twitter, or a “tweet chat.” A Twitter chat is a public discussion on Twitter around a specific hashtag. During a tweet chat, there is a designated moderator—brand or individual—who ask questions and facilitates the discussion at a predetermined time. For example, the “#NephJC” is a nephrology journal club (www.nephjc.com) that uses Twitter to discuss the research, guidelines, and editorials that are driving nephrology. After the chat the conversations are archived by Symplur (www.symplur.com) and in Storify (www.storify.com). You can also follow posts of “#NephJC” on Pubmed.

No published studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of Twitter as an intervention to increase living kidney donation. However, there are commonly used hashtags in the field of organ donation (Table 2). The examination of Twitter and hashtags as a strategy to increase access to LDKT should be a future area of research.

Table 2.

Common Hashtags Used in Organ Donation from RiteTag.com

| Unique tweets per hour | Retweets per hour | Hashtag exposure per hour | Tweets with images (%) | Tweets with links (%) | Tweets with mentions (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hashtags that get seen immediately | ||||||

| #life | 292 | 137 | 1,401,396 | 32.88 | 47.26 | 17.12 |

| Hashtags that get seen over time | ||||||

| #organdonation | 4 | 4 | 3,417 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| #organ | 4 | 0 | 1,208 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| #lives | 4 | 0 | 721,396 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| #transplant | 4 | 4 | 51,925 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| #fortis | 4 | 0 | 55,212 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| #heart | 12 | 26 | 10,450 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| #awareness | 8 | 13 | 29,933 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 |

| #time | 33 | 17 | 172,600 | 51.25 | 75.76 | 36.36 |

| #thanks | 29 | 54 | 77,617 | 13.79 | 27.59 | 58.62 |

| #organdonor | 4 | 0 | 6,138 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| #btg | 4 | 0 | 2,529 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| #show | 42 | 25 | 74,246 | 19.05 | 100.00 | 9.52 |

| #giving | 4 | 0 | 7,312 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| #families | 8 | 0 | 84,412 | 50.00 | 100.00 | 50.00 |

| #transplantation | 4 | 0 | 47,817 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| #day | 25 | 21 | 83,442 | 16.00 | 48.00 | 0.00 |

| #people | 79 | 29 | 5,235,050 | 5.06 | 94.94 | 0.00 |

| #death | 21 | 4 | 20,696 | 19.05 | 80.95 | 19.05 |

| #donatelife | 4 | 0 | 16,646 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

Applications: Moving to Mobile

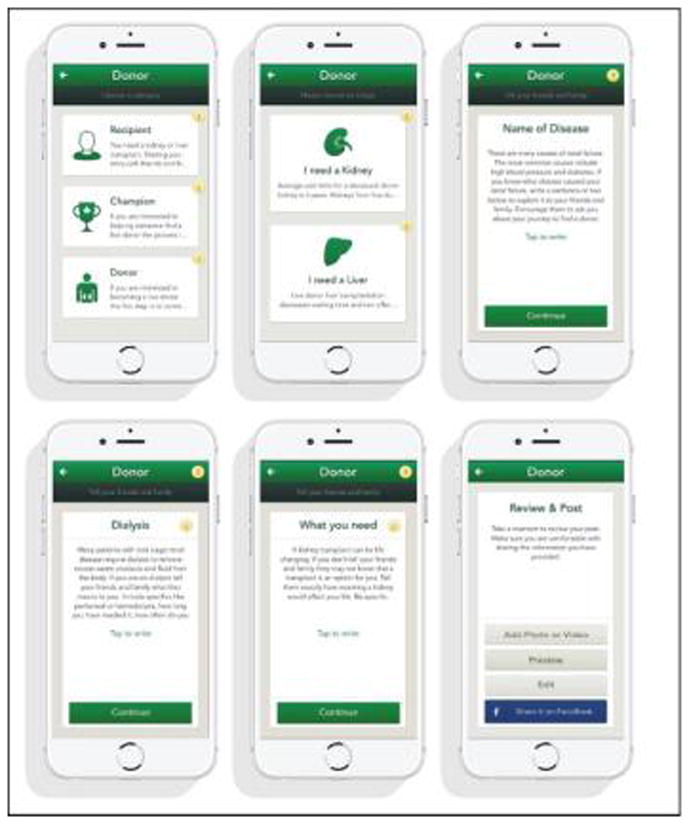

With the arrival of the smartphone and mobile medical devices, mobile health (mHealth) applications have become a reality for patients, and are emerging in the field of organ transplantation. Fleming et al., 2017 [39] recently reviewed emerging mHealth applications in the field of solid organ transplantation. There has been one smartphone application developed specifically for transplant candidates in need of a living kidney donor. The Donor smartphone app was developed by Johns Hopkins University, and is designed to help transplant candidates who face many barriers to finding a living donor, including hesitance to initiate conversations, lack of knowledge, and not knowing who in their network to ask. Using the Donor smartphone app allows transplant candidates to post their need for a living donor directly to their Facebook page. The Donor smartphone app provides step-by step instructions that helps transplant candidates to construct and share “their story” with their expanded social network (Figure 1), and includes vetted information about risk, benefits, and the process of living donation. Development of this app was grounded in ethical consideration of the critical need for veracity or truthfulness when using social media to communicate about living donation [19], such that the Donor smartphone app’s guided approach to facilitating living donation can help ensure transplant candidates are able to both accurately represent themselves and why they need a transplant, and to tell their best story in the hopes of securing a potential donor [27].

Figure 1.

The Donor Smartphone App

In a pilot study of the app among 54 adult transplant candidates, 24% of patients in the intervention group had at least one living donor referral. Transplant candidates using the app were significantly more likely to have a live donor referral compared with matched controls on the waitlist over 10-months after enrollment (odds ratio 6.61,95% CI 2.43–17.98;p < 0.001) [40]. Importantly, over 70% of study participants rated the app to be good or excellent with regards to installation, readability, simplicity, clarity, and informativeness; 83% of study participants rated the app to be good or excellent with regards to the installation process. Most (90%) study participants rated good or excellent with regards to readability, 69% with regards to simplicity, 76% with regards to clarity [40]. The Donor smartphone app is currently being evaluated as part of a multi-site clinical trial of the Live Donor Champion advocacy-training program [41, 24].

Conclusions

While formal, published evidence on the effectiveness of social media use by transplant candidates to find a willing living kidney donor is at an early stage, there are many patient-driven efforts utilizing social media platforms. As social media platforms continue to grow and expand, transplant providers, researchers and policy makers should commit to understanding and facilitating the use of social media to support patients who are interested in using social media as a tool to find a living kidney donor, and reduce disparity in access to the life-saving gift of organ transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant number K01DK114388-01.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- LDKT

living donor kidney transplantation

- LKDN

Living Kidney Donors Network

- mHealth

mobile health

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Macey Henderson declares no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.LaPointe Rudow D, Hays R, Baliga P, Cohen DJ, Cooper M, Danovitch GM, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(4):914–22. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USRDS. Ch 7: Transplantation. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2015. Annual Data Report: End-stage Renal Disease (ESRD) in the United States. 2015 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Network for Organ Sharing. 2016 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. Patients’ willingness to talk to others about living kidney donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):25–31. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnieh L, McLaughlin K, Manns BJ, Klarenbach S, Yilmaz S, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Barriers to living kidney donation identified by eligible candidates with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;26(2):732–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Mandelbrot DA. The decline in living kidney donation in the United States: random variation or cause for concern? Transplantation. 2013;96(9) doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318298fa61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren DS, Zachary AA, Sonnenday CJ, King KE, Cooper M, Ratner LE, et al. Successful renal transplantation across simultaneous ABO incompatible and positive crossmatch barriers. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(4):561–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montgomery JR, Berger JC, Warren DS, James N, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Outcomes of ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2012;93(6):603. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318245b2af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiebe C, Pochinco D, Blydt-Hansen T, Ho J, Birk P, Karpinski M, et al. Class II HLA Epitope Matching—A Strategy to Minimize De Novo Donor-Specific Antibody Development and Improve Outcomes. Am J Tanspalnt. 2013;13(12):3114–22. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnieh L, McLaughlin K, Manns BJ, Klarenbach S, Yilmaz S, Taub K, et al. Evaluation of an education intervention to increase the pursuit of living kidney donation: a randomized controlled trial. Prog Transplant. 2011;21(1):36–42. doi: 10.1177/152692481102100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coorey GM, Paykin C, Singleton-Driscoll LC, Gaston RS. Barriers to preemptive kidney transplantation. Am J Nurs. 2009;109(11):28–37. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000363348.29227.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd DM, Ellison NB. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2007;13(1):210–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shannon Greenwood AP, Duggan Maeve. Social Media Update. Pew Research Center, Internet Society, and Tech; Nov 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duggan M, Ellison NB, Lampe C, Lenhart A, Madden M. Social media update 2014. Pew Research Center; 2015. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sloan L, Quan-Haase A. The SAGE handbook of social media research methods. Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgess J, Marwick A, Poell T. SAGE Handbook of Social Media: Introduction. SAGE Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruns A. Making sense of society through social media. Social Media+ Society. 2015;1(1):2056305115578679. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grahl T. Out: think. 2013. The 6 types of social media. [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Henderson ML, Clayville KA, Fisher JS, Kuntz KK, Mysel H, Purnell TS, et al. Social media and organ donation: Ethically navigating the next frontier. Am J Transplant. 2017 doi: 10.1111/ajt.14444. This article lays out an ethical framework for the use of social media in living donation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):893–901. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray K, Sanchez F, Bright G, Cheng A. E-Collaboration in Biomedical Research: Human Factors and Social Media. Advancing Medical Practice Through Technology. Applications for Healthcare Delivery, Management, and Quality. 2013:102–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Allen MB, Reese PP. Transforming Living Kidney Donation with a Comprehensive Strategy. PLoS Med. 2016;13(2):e1001948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001948. This paper discusses raising the profile of living kdiney donation among the public, and professionlizing the practice of helping patients find a donors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnieh L, Collister D, Manns B, Lam NN, Shojai S, Lorenzetti D, et al. A Scoping Review for Strategies to Increase Living Kidney Donation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(9):1518–27. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01470217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt H, Rodrigue J, Dew MA, Schaffer RL, Henderson ML, Bloom R, Kacani P, Shim P, Bolton L, Sanchez W, Lentine KL. Strategies for Increasing Knowledge, Communication and Access to Living Donor Transplantation: An Evidence Review to Inform Patient Education. Curr Transplant Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s40472-018-0181-1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Accessed November 6, 2016];MatchingDonors.com. http://matchingdonors.com/life/index.cfm.

- 26.Caplan AL. Organs.com: new commercially brokered organ transfers raise questions. The Hastings Center Rep. 2004;34(6):8–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bramstedt KA, Cameron AM. Beyond the Billboard: The Facebook-Based Application, Donor, and Its Guided Approach to Facilitating Living Organ Donation. Am J Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ajt.14004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips S. A brief history of Facebook. the Guardian. 2007;25(7) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameron AM, Massie A, Alexander C, Stewart B, Montgomery RA, Benavides N, et al. Social media and organ donor registration: the Facebook effect. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(8):2059–65. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Kazley SA, Hamidi B, Balliet W, Baliga P. Social Media Use Among Living Kidney Donors and Recipients: Survey on Current Practice and Potential. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(12):e328. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6176. This study examines social media use among kidney donors and recipients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pineda N. Facebook tips: What’s the difference between a Facebook page and group? The Facebook. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang A, Anderson EE, Turner HT, Shoham D, Hou SH, Grams M. Identifying potential kidney donors using social networking web sites. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(3):E320–E6. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.KidneyBuzz.com. Welcome to the Find A Kidney Donor Program. KidneyBuzz.com. 2017 https://www.kidneybuzz.com/find-a-kidney-donor-campaign/

- 34.Carlson N. The real history of Twitter. Business insider. 2011;13:04–13. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwak H, Lee C, Park H, Moon S, editors. What is Twitter, a social network or a news media?. Proceedings of the 19th international conference on World wide web; 2010; ACM; [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullin B. Report: Journalists are largest, most active verified group on Twitter. Poynter. 2015 May 26; [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lincoln C. 6th Annual Shorty Awards Winner in Social Good Campaign, Twitter Campaign. Small Agency. Sawhorse Media; 2013. [Accessed Jan 20 2017]. http://shortyawards.com/6th/sfbatkid. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsur O, Rappoport A, editors. What’s in a hashtag?: content based prediction of the spread of ideas in microblogging communities. Proceedings of the fifth ACM international conference on Web search and data mining; 2012; ACM; [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleming J, Taber D, McElligott J, McGillicuddy J, Treiber F. Mobile Health in Solid Organ Transplant: The Time Is Now. Am J Transplant. 2017 doi: 10.1111/ajt.14225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar K, King EA, Muzaale A, Konel J, Bramstedt KA, Massie A, et al. A smartphone app for increasing live organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(12):3548–53. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garonzik-Wang JM, Berger JC, Ros RL, Kucirka LM, Deshpande NA, Boyarsky BJ, et al. Live donor champion: finding live kidney donors by separating the advocate from the patient. Transplantation. 2012;93(11):1147. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824e75a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millen DR, Yang M, Whittaker S, Feinberg J. ECSCW 2007. Springer; 2007. Social bookmarking and exploratory search; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Archambault PM, van de Belt TH, Grajales FJ, III, Faber MJ, Kuziemsky CE, Gagnon S, et al. Wikis and collaborative writing applications in health care: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(10) doi: 10.2196/jmir.2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barton ET, Barton EA, Barton S, Boyer CR, Brosnan J, Hill P, et al. Using Technology to Enhance Extension Education and Outreach. HortTechnology. 2017;27(2):177–86. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinecke K, Nguyen MK, Bernstein A, Näf M, Gajos KZ, editors. Doodle around the world: Online scheduling behavior reflects cultural differences in time perception and group decision-making. Proceedings of the 2013 conference on Computer supported cooperative work; 2013; ACM; [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waycott J. Appropriating tools and shaping activities: The use of PDAs in the workplace. Mobile World. 2005:119–39. [Google Scholar]