Abstract

Objective

We conducted a neuroimaging analysis to understand the neuroanatomical correlates of gray matter loss in a group of mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease patients who developed delusions.

Methods

With data collected as part of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, we conducted voxel-based morphometry to determine areas of gray matter change in the same Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative participants, before and after they developed delusions.

Results

We identified 14 voxel clusters with significant gray matter decrease in patient scans post-delusional onset, correcting for multiple comparisons (false discovery rate, p < 0.05). Major areas of difference included the right and left insulae, left precuneus, the right and left cerebellar culmen, the left superior temporal gyrus, the right posterior cingulate, the right thalamus, and the left parahippocampal gyrus.

Conclusions

Although contrary to our initial predictions of enhanced right frontal atrophy, our preliminary work identifies several neuroanatomical areas, including the cerebellum and left posterior hemisphere, which may be involved in delusional development in these patients.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, delusions, psychosis, voxel-based morphometry

Introduction

Delusions are common symptoms that are estimated to occur in approximately one-third of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias (Ropacki and Jeste, 2005). They are clinically significant and are often associated with a number of adverse clinical outcomes, including increased caregiver burden (Fischer, 2012), functional impairment (Fischer et al., 2012), and accelerated cognitive decline(Sweet et al., 2010). While these symptoms have been well described in the literature, the precise neuroanatomical mechanisms that are responsible for these symptoms to date have been poorly understood. Moreover, medications used to treat these symptoms have been demonstrated to be only modestly effective and have been demonstrated to lead to increased mortality (Schneider et al., 2005), emphasizing the need for different treatment approaches. Ismail et al. (2011) recently reviewed the existing literature on the neurobiology of delusions in AD and established that many previous studies failed to differentiate delusions from hallucinations, and also considered paranoid and misidentification delusions together (Ismail et al., 2011). As a result, it has been difficult to determine the neuroanatomical correlates of delusions based on analyses of existing data. A recent review of neuroimaging studies (Ismail et al., 2012) tends to favor focal atrophy in the right frontal region, consistent with the hypothesis that damage to the right frontal lobe disrupts the monitoring function of the brain, thus resulting in the development of delusional thoughts. In his review, eight of 10 Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) studies showed diminished blood flow to the right hemisphere, the vast majority to the right frontal lobe. As well, six of the seven volumetric studies showed focal atrophy in the right hemisphere, the majority to the right frontal lobe. Focal damage to the right hemisphere has been postulated as a possible mechanism of delusion formation (Devinsky, 2009). According to Devinsky and colleagues, delusions may arise when the right hemisphere, which traditionally provides a monitoring function, is underactive and is unable to inhibit the left hemisphere.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) is a repository of clinical and biomarker data collected on nearly 800 North Americans diagnosed at baseline with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or early stage AD. Access to this data set provides a unique opportunity for examining the neural correlates of symptoms such as delusions. This study conducted voxel-based morphometry (VBM) on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans of a subset of patients before the onset of delusions (visit on average 6 months prior to onset of delusions) and compared them to scans from the first visit at which delusions were reported. We aimed to identify what brain regions undergo atrophy during the transition from non-delusional to delusional status. While we have explored this question in a cross-sectional fashion (Ting et al., 2015), few studies to date have looked at this question longitudinally. The majority of cross-sectional studies conducted to date demonstrate gray matter volume loss in AD patients with psychosis when compared with AD patients without psychosis, specifically involving the frontal lobes (Murray et al., 2014). Two of three CT studies comparing AD patients with and without delusions showed focal atrophy in the right frontal areas (Forstl et al., 1991; Forstl et al., 1994). MRI studies to date conducted using VBM and region of interest analysis showed a broader range of findings, including right frontoparietal, left frontal, and left claustrum (Bruen et al., 2008); right hippocampus (Serra et al., 2010) and left medial orbitofrontal; and superior temporal in female subjects only (Whitehead et al., 2012). In one of the few longitudinal studies carried out to date, Nakaaki et al. compared the baseline MRIs of patients who developed delusions (n=18) with the MRIs of patients who did not (n=35) using VBM, establishing volume changes in the bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, right posterior cingulate gyrus, right orbital frontal cortex, right anterior cingulate, left insula, and both sides of the inferior frontal cortices (Nakaaki et al., 2013). The study concluded that structural changes in the frontal and medial temporal lobes may mediate or contribute to the development of delusions. However, the study only looked at baseline scans and did not compare volumetric changes over time pre-delusion and post-delusion onset, limiting the conclusions. Our study is the first of its kind to compare gray matter changes pre-delusion and post-delusion onset. Based on our previous work in this area and the results of prior studies (Ismail et al., 2012), we hypothesized that delusion onset in the same patients would be associated with greater atrophy in the right hemisphere regions, specifically the right frontal lobe.

Methods

The present study examined 24 ADNI participants at baseline with delusions (D+) and 1.5-Tesla MRI scans selected from ADNI, and who also had MRI scans on average 6 months prior to delusional onset (D−). All participants had a diagnosis of MCI at baseline. The ADNI database includes data from more than 800 participants diagnosed at baseline as elderly control subjects (n = 200), amnestic MCI (n = 400), or early AD (n = 200), collected from 50 sites across North America. A diagnosis of MCI (Petersen, 2004) was based on ‘Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores between 24–30 (inclusive), a memory complaint,…objective memory loss measured by education-adjusted scores on Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) Logical Memory II, a CDR of 0.5, absence of significant enough levels of impairments in other cognitive domains so that criteria for dementia are not met, largely preserved activities of daily living, and an absence of dementia’ (ADNI, 2015). Diagnosis of probable AD was based on National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke - Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria (McKhann et al., 2011). At each visit, determination of MCI or AD was made by a neurologist or psychiatrist based on clinical data from that study visit, including MMSE, clinical dementia rating (CDR), and neuropsychological test scores. The CDR is a global measure of dementia severity often used for staging and ranges from a score of 0 (no dementia) to 3 (severe dementia). A Central Review Committee ensured that conversion from MCI to AD was evaluated consistently across sites using standard criteria. Onset of delusions was determined from a score of 1 on the delusions item of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire (NPI-Q) completed by a knowledgeable informant. The NPI-Q delusion item asks ‘Does the patient believe that others are stealing from him or her or planning to harm him or her in some way?’ (Informants are asked to respond ‘yes’ to each symptom if the patient had the symptom during the previous month.) Participants were included in our study if they had a baseline diagnosis of MCI, developed delusions during study participation, and had an MRI scan from the visit at which delusions were first reported and a scan from the immediately preceding visit. Individuals who also developed hallucinations were excluded. Seventy (70.8%) of the participants progressed to AD by the onset of delusions. Pre-processed T1 MR images were downloaded from the ADNI server.

We conducted VBM to characterize the atrophy patterns associated with the time-based onset of delusions in MCI, in SPM8 software guided by John Ashburner’s VBM Tutorial (Ashburner, 2010). We utilized the VBM8 toolbox, which modified the traditional processing pipeline to better compare longitudinal scans. Images were assessed for gross anatomical abnormalities and approximately registered to an average Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template of 152 T1 MRI scans. All images were normalized to participants’ baseline scans. The images were modulated and smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel at 8-mm full-width half maximum. The resulting images were entered into a general linear model for a dependent two-sample t-test. All significance values were corrected for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate p< 0.05 with no masking. Only clusters greater than 50 voxels in size were considered to minimize false positives. Cluster coordinates in MNI space were converted into Talairach coordinates, and neuroanatomical location was identified using a computerized Talairach Atlas. Informed consent of participants for neuroimaging research was obtained at all ADNI partner sites. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board.

Results

The mean age of the sample at baseline was 74.13 (standard deviation (SD)=6.1, 56–84) with the majority of the sample composed of male participants (n=14, 58.3%). One participant was identified as Asian, while the remaining 23 were identified as White. The mean MMSE at baseline was 26.54 (SD=1.88; 24–30), which decreased to 21.29 (SD=5.86, 9–30) by onset of delusions. The CDR for all patients at baseline was 0.5, with the mean CDR at delusion onset being 1.02 (SD=0.5). Seven participants (29.2% of participants) had a CDR of 0.5 at D+, 13 participants (54.2%) had a CDR of 1.0, and four participants (16.7%) had a CDR of 2.0 at D+. Detailed demographics information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of longitudinal MRI VBM study participants

| Pre-delusion visit (D−) |

Delusion visit (D+) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline age | 74.13 (SD = 6.10) | |

| Education (years) | 16.08 (SD = 3.06) | |

| MMSE | 26.54 (SD = 1.89) | 21.29 (SD = 5.86) |

| Diagnosis | MCI (N = 24) | MCI (N = 7) |

| AD (N = 17) | ||

| Delusion severity | N/A | 1—mild (N = 13) |

| 2—moderate | ||

| (N = 10) | ||

| 3—severe (N = 1) | ||

| Total NPI-Q score | 4.25 (SD = 3.59) | 7.79 (SD = 5.07) |

| Global CDR | 0.5 (N = 24) | 0.5 (N = 7) |

| 1 (N = 13) | ||

| 2 (N = 4) | ||

| CDR sum of boxes | 3.96 (SD = 2.21) | 5.90 (SD = 2.93) |

| Visit number | Month 6 (N = 5) | Month 12 (N = 5) |

| Month 12 (N = 6) | Month 18 (N = 6) | |

| Month 18 (N = 3) | Month 24 (N = 3) | |

| Month 24 (N = 3) | Month 36 (N = 3) | |

| Month 36 (N = 7) | Month 48 (N = 7) |

VBM, voxel-based morphometry; SD, standard deviation; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire; CDR, clinical dementia rating.

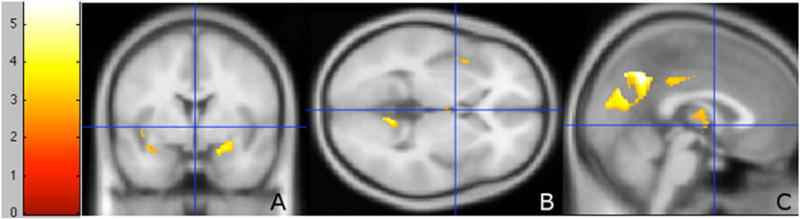

Voxel-based morphometry analyses comparing MRI brain scans of MCI/AD patients who developed delusions with the scans obtained prior to delusion onset revealed significant differences in gray matter morphology (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Suprathreshold voxel clusters between D+ MCI/AD patients compared with the same patients prior to delusional onset (D−). (A) coronal section, (B) axial section, and (C) sagittal section. Contrast D > D+, paired two-sample t-test in a general linear model. Significance threshold (FDR) corrected, p < 0.05. Greater value on scale indicates greater voxel significance.

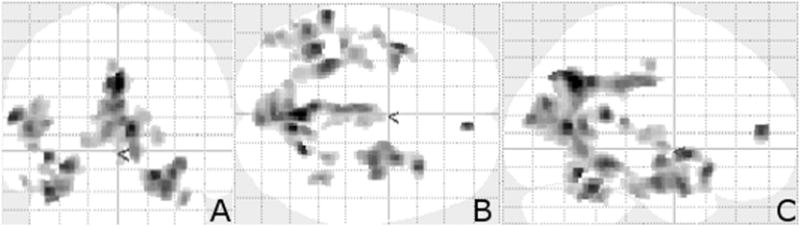

Contrary to our predictions, the majority of the clusters were in the left hemisphere of the brain (Figure 2), and included the left precuneus, the right and left insulae, the right and left cerebellar culmen, the left superior temporal gyrus, the left parahippocampal gyrus, the right thalamus, and the right posterior cingulate (Table 2). In total, 14 suprathreshold voxels at a threshold significance of p < 0.05 (false discovery rate corrected for multiple comparisons) were identified.

Figure 2.

Transparent brain projection of suprathreshold voxel clusters between D+ MCI/AD patients compared with the same patients prior to delusional onset (D−). Significance threshold FDR corrected p < 0.05. (A) coronal projection, (B) axial projection, and (C) sagittal projection. The majority of the significant voxel clusters are located in the left posterior regions of the brain. These transparent projections permit a complete view of all significant clusters.

Table 2.

Suprathreshold voxel clusters in longitudinal VBM analysis of ADNI MCI/AD participants who developed delusions, FDR corrected p < 0.05 with cluster size greater than or equal to 50

| Suprathreshold voxel clusters, p < 0.05 FDR corrected | Puncorr (cluster) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Cluster no. | Coordinates (Talairach)

|

Cluster size KE | Location (nearest gray matter) | T | qFDR Corr (peak) | |||

| X | Y | Z | ||||||

| 1 | −2 | −58 | 32 | 3011 | Left precuneus | 5.59 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 18 | −52 | −13 | 103 | Right cerebellar culmen | 5.16 | 0.022 | 0.274 |

| 3 | −57 | −40 | 17 | 902 | Left superior temporal gyrus | 5.12 | 0.022 | 0.004 |

| 4 | −38 | −44 | −19 | 252 | Left cerebellar culmen | 5.12 | 0.022 | 0.095 |

| 5 | −38 | 4 | 1 | 350 | Left insula | 4.99 | 0.022 | 0.054 |

| 6 | −29 | −38 | −7 | 633 | Left parahippocampal gyrus | 4.94 | 0.022 | 0.013 |

| 7 | 5 | 44 | 18 | 62 | Right medial frontal gyrus | 4.93 | 0.022 | 0.397 |

| 8 | 29 | 16 | −5 | 1180 | Right insula | 4.85 | 0.022 | 0.001 |

| 9 | −40 | −31 | 15 | 90 | Left superior temporal gyrus | 4.11 | 0.023 | 0.306 |

| 10 | 35 | −41 | −23 | 90 | Right cerebellar culmen | 4.07 | 0.023 | 0.306 |

| 11 | −45 | −8 | 5 | 53 | Left insula | 3.80 | 0.025 | 0.436 |

| 12 | 23 | −38 | −12 | 75 | Right cerebellar culmen | 3.79 | 0.025 | 0.351 |

| 13 | 3 | −18 | 12 | 200 | Right thalamus | 3.55 | 0.028 | 0.133 |

| 14 | 19 | −53 | 6 | 74 | Right posterior cingulate | 3.51 | 0.028 | 0.354 |

VBM, voxel-based morphometry; ADNI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; FDR, false discovery rate.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first VBM study to compare MRI scans of AD/MCI patients, before and after delusion onset. Previous MRI studies looking at gray matter volumetric changes in AD patients with delusions have favored increased atrophy, most marked in the frontal lobes (Bruen et al., 2008; Serra et al., 2010; Whitehead et al., 2012). Contrary to our predictions, onset of delusions in our sample was associated with significant volume reductions predominately in the left posterior hemisphere and also in the cerebellum. Somewhat unexpectedly, fewer gray matter changes were noted in frontal or temporal lobe regions. The results are consistent to some degree with the findings of Nakaaki et al. who conducted VBM to compare AD patients who did and did not develop delusions over time (Nakaaki et al., 2013). In that study, gray matter atrophy was also observed in the parahippocampal gyri bilaterally, the right posterior cingulate gyrus, and the right insula. However, changes were also observed in the inferior frontal cortex and the right anterior cingulate gyrus and involved primarily the right hemisphere, contrary to our findings. This study only looked at baseline changes, however, and did not compare changes over time pre-delusion and post-delusion onset.

One potential theory that may explain our findings is that damage to the posterior brain regions may result in increased connectivity to the frontal lobes. It is possible that this hyperconnectivity may trigger delusion formation. This has been postulated as a mechanism of delusion formation by Nagahama et al. who found a correlation between delusions of theft and hyperperfusion of the frontal lobes in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (Nagahama et al., 2007). It has also been observed in patients with behavioral variant frontal–temporal dementia (Farb et al., 2013). In addition, posterior brain regions, including the precuneus and posterior cingulate gyrus, are part of the default mode network, and disruptions in default mode network connectivity have been implicated both in AD (Pievani et al., 2011) and psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia (Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2009).

Finally, the cerebellum has been implicated as a region of interest in patients with psychotic disorders, specifically schizophrenia (Okugawa et al., 2002), although the precise mechanism by which these changes are induced is unclear. According to Andreasen and colleagues, the cerebellum plays a critical role in coordinating sensory-motor inputs, and damage to the cerebellum may impair this coordinating function, resulting in the emergence of psychotic symptoms (Andreasen et al., 1998). Another potential explanation for the disparate findings is that different types of delusions may arise from damage to different regions of the brain. Nakatsuka et al. conducted SPECT scans on 59 AD patients and discovered different delusion types correlated with damage to different brain regions (Nakatsuka et al., 2013). Similarly, Spalletta et al. (2013) correlated somatic delusions in patients with schizophrenia with reduced gray matter volume in the left fronto-insular cortex, suggesting that in other psychotic illnesses, subtypes of delusions may be associated with damage to specific neuroanatomical regions (Spalletta et al., 2013).

While the findings of this study are of interest, there are some limitations that should be noted. The sample size was quite small (24 patients) and this may have affected the validity of our findings. While all patients had a diagnosis of MCI at baseline, not all had progressed to AD at the time of delusion onset; thus, the sample is heterogeneous with respect to rate of progression of cognitive impairment. We did not identify delusional subtypes. However, the NPI-Q delusion item asks exclusively about the presence of paranoid ideation/delusions of theft in the previous month. Individuals who developed transient delusions that resolved prior to the second study visit, or who developed other types of delusions (such as misidentification delusions), would not be captured in the present study. It is possible that some delusions captured by the NPI-Q could relate to systemic illness or medication side-effects that are independent of the patient’s neurodegenerative disease. However, it seems unlikely that patients experiencing a delirium would be able to complete the clinical assessment and MRI. We did not compare our findings to a control group of AD subjects who did not develop delusions. Relatively few ADNI participants developed delusions, and those for whom delusions were first reported on the M6 (sixth month from study baseline) study visit could not be included in our study because MRI was not performed at baseline. As a result, it is possible that the changes we observed in the cerebellum and posterior left hemisphere may be attributable to factors other than delusions. Moreover, most of the changes we found were clustered in the left posterior lobe, contrary to our predictions. Finally, it is hard to determine the clinical significance of volumetric brain changes over such a short time frame (pre-delusion and post-delusion onset) as it is still not clear at what point in the disease trajectory delusions develop. Future studies should address these limitations.

In conclusion, we conducted a VBM study investigating the gray matter changes associated with delusion onset in MCI/AD subjects. The results of our study suggest, although preliminary, that delusions in AD may arise from damage to the posterior left hemisphere and cerebellum. Understanding the role of these brain regions in delusion formation, both in AD and in other diseases, may in time lead to the development of targeted treatments that would reduce disease burden caused by delusions.

Key points.

Delusions occur in up to 50% of patients with AD.

Studies to date have been limited in their ability to identify neural correlates of delusions in MCI/AD.

Most studies to date have been cross-sectional in design and did not separate delusions from psychosis, thus limiting conclusions.

Our study is the first longitudinal study to examine cerebral correlates of delusions using data from ADNI and demonstrates delusions in AD that may be associated with focal decrease in gray matter in the cerebellum and posterior left hemisphere.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), Catalyst Grant Program: ‘Secondary Analysis of Neuroimaging Databases’ for Study Funding and the ADNI for providing images and clinical variables for analysis. We also thank Ms. Danielle Turnbull for her contributions in preparing clinical study data for analysis, summarizing the demographics information, and providing important suggestions for improvement of the manuscript.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the ADNI (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Bio-tech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Rev, 5 December 2013, Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of Califor-nia, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. CF, WT, CM, and TS were supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Catalyst Grant in the conduction of this study.

Footnotes

This work was previously presented as a poster presentation at the 2014 American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry’s Annual Meeting, in Orlando, Florida, USA. The abstract from the poster presentation is archived in Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 22:3, Supplement 1, pp 132–133.

Conflict of interest

Windsor Ting reports no disclosures. Dr. Fischer reports no disclosures. Dr. Millikin reports no disclosures. Dr. Ismail has served on an advisory board for Merck. Dr. Schweizer reports no disclosures.

References

- ADNI. ADNI study documents. 2015 http://adni.loni.usc.edu/

- Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O’Leary DS. “Cognitive dysmetria” as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfunction in cortical-subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:203–218. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J. VBM tutorial. University College London; 2010. http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/~john/misc/VBMclass10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bruen PD, McGeown WJ, Shanks MF, Venneri A. Neuroanatomical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain J Neurol. 2008;131:2455–2463. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O. Delusional misidentifications and duplications: right brain lesions, left brain delusions. Neurology. 2009;72:80–87. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338625.47892.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farb NA, Grady CL, Strother S, et al. Abnormal network connectivity in frontotemporal dementia: evidence for prefrontal isolation. Cortex. 2013;49:1856–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CE, Ismail Z, Schweizer TA. Delusions increase functional impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33:393–399. doi: 10.1159/000339954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CE, Ismail Z, Schweizer TA. Impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manage. 2012;2:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Forstl H, Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R. Neuroanatomical correlates of clinical mis-identification and misperception in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstl H, Burns A, Levy R, Cairns N. Neuropathological correlates of psychotic phenomena in confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:53–59. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail Z, Nguyen MQ, Fischer CE, Schweizer TA, Mulsant BH. Neuroimaging of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail Z, Nguyen MQ, Fischer CE, et al. Neurobiology of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:211–218. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PS, Kumar S, Demichele-Sweet MA, Sweet RA. Psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama Y, Okina T, Suzuki N, et al. Classification of psychotic symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:961–967. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180cc1fdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaaki S, Sato J, Torii K, et al. Decreased white matter integrity before the onset of delusions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: diffusion tensor imaging. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:25–29. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S38942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka M, Meguro K, Tsuboi H, et al. Content of delusional thoughts in Alzheimer’s disease and assessment of content-specific brain dysfunctions with BEHAVE-AD-FW and SPECT. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:939–948. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okugawa G, Sedvall G, Nordstrom M, et al. Selective reduction of the posterior superior vermis in men with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;55:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pievani M, de Haan W, Wu T, Seeley WW, Frisoni GB. Functional network disruption in the degenerative dementias. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:829–843. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70158-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropacki SA, Jeste DV. Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2022–2030. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934–1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra L, Perri R, Cercignani M, et al. Are the behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease directly associated with neurodegeneration? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:627–639. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalletta G, Piras F, Alex Rubino I, Caltagirone C, Fagioli S. Fronto-thalamic volumetry markers of somatic delusions and hallucinations in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;212:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet RA, Bennett DA, Graff-Radford NR, Mayeux R, National Institute on Aging Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study G. Assessment and familial aggregation of psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease from the National Institute on Aging Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study. Brain. 2010;133:1155–1162. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting WK, Fischer CE, Millikin CP, et al. Grey matter atrophy in mild cognitive impairment/early Alzheimer disease associated with delusions: a voxel-based morphometry study. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12:165–172. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150204130456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead D, Tunnard C, Hurt C, et al. Frontotemporal atrophy associated with paranoid delusions in women with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:99–107. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211000974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]