Summary

The gut has great importance for the commercial success of poultry production. Numerous ion transporters, exchangers, and channels are present on both the apical and the basolateral membrane of intestinal epithelial cells, and their differential expression along the crypt-villus axis within the various intestinal segments ensures efficient intestinal absorption and effective barrier function. Recent studies have shown that intensive production systems, microbial exposure, and nutritional management significantly affect intestinal physiology and intestinal ion transport. Dysregulation of normal intestinal ion transport is manifested as diarrhoea, malabsorption, and intestinal inflammation resulting into poor production efficiency. This review discusses the basic mechanisms involved in avian intestinal ion transport and the impact of development during growth, nutritional and environmental alterations, and intestinal microbial infections on it. The effect of intestinal microbial infections on avian intestinal ion transport depends on factors such as host immunity, pathogen virulence, and the mucosal organisation of the particular intestinal segment.

Keywords: intestine, ion transport, chicken, turkey, poultry, diarrhea, enteritis, malabsorption

Introduction

Advances in poultry management and disease prophylaxis have significantly improved the growth performance. However, intestinal diseases remain a substantial challenge for the production goals of modern poultry industry and raise the concerns for increased morbidity and mortality, poor growth efficiency and resultant economic losses. The intestinal epithelial lining has a duel task of absorbing nutrients via numerous ion channels and transporters present on the apical intestinal epithelial border and, at the same time, defending the host from the toxins and pathogens present in the intestinal lumen. Intestinal ion transport is affected by nutrition, microflora, and environment, the most important factors that influence poultry intestinal health. Recent studies on virulence factors of pathogens and their complex interaction with the host intestinal ion transport have shed light on the mechanism of many enteric infections.

Organisation of the intestinal mucosa

The intestinal luminal surface represents the largest area of the body that is in direct contact with environmental contaminants and microbial agents, and its most striking anatomical features are its segmental division and the organisation of the intestinal mucosa into the crypt-villus axis. The length of villi decreases from the proximal to the distal end of the intestine. For instance, in broiler chicken, the average villous length is 1.80 μm in the duodenum (Leeson et al., 2005, Chou et al., 2009, Panda et al., 2009) and 1.08 μm in the colorectal region (Nasrin et al., 2012). The presence of a crypt-villus axis along the length of intestine has immediate functional implications. While the immature crypt epithelium is primarily involved in ion secretion, the mature villus epithelium derived from the crypts is involved in nutrient absorption. At the cellular level the epithelial lining is composed of a single layer of columnar epithelial cells and interepithelial tight junctions (TJ) present at the apical-most region of the paracellular space between adjacent enterocytes (Figure 1). Tight junctions consist of an array of membrane-spanning proteins (e.g., barrier forming occludin and pore forming claudins) that are linked to the cytoskeleton by the cytoplasmic plaque protein zona occludin. Thus, such an intestinal barrier, consisting of a surface epithelium with intercellular TJs, not only permits the selective movement of ions, nutrients and water, but also restricts the translocation of microbes and toxins from the lumen (Podolsky, 1997).

Figure 1. Basic ion absorption mechanisms in intestinal epithelial cells. An efficient absorption of Na+ involves transcellular (multiple ion transporters on the apical and basolateral membrane) and paracellular routes.

Basic scheme of intestinal ion transport

The lipid bilayers in the plasma membrane of the intestinal epithelial cells are relatively impermeable to ions which necessitates the presence of special carriers on the cell membrane to facilitate the transport of ions from the intestinal lumen into the epithelial cells and vice versa. These special carrier proteins are predominantly either transporters or ion channels. Transporters are proteins which bind a specific solute and is subsequently moved across the membrane due to a conformational change in the protein while ion channels are proteins that form charge- and size-specific pores in the plasma membrane. This basic scheme of ion transport across the intestinal lining permits efficient ion homeostasis. Crucial to this process is the polarity of the epithelial cells conferred by the presence of the apical TJs which ensures that the apical and basolateral ion transporters remain in their respective locations in the cell membrane (Figure 1).

Ion transport at the membranes occurs as follows. At the basolateral membrane, an ion gradient generated by the ATP driven movement of Na+ and K+ via the Na+K+ATPase (sodium potassium ATPase, commonly referred to as the ‘sodium pump’) helps passive diffusion of Na+, K+, and Cl– through the Na+-K+-Cl- cotransporter NKCC1 (Figure 1). At the apical membrane, three major mechanisms of sodium absorption are present. The first mechanism involves the sodium glucose linked transporter (SGLT-1), which is stimulated by the presence of glucose in the lumen. Oral rehydration solutions containing sugar and salt make use of this mechanism to significantly increase the absorption of sodium. Importantly, this movement of sodium and glucose also establishes a gradient that stimulates the movement of sodium and water through the paracellular space, which is referred to as the ‘sodium drag’. The second mechanism pertains to the sodium hydrogen exchanger isoform-3 (NHE3) which is present throughout small intestine and exchanges one sodium ion for every proton. This is an important mechanism of post-prandial sodium absorption. The electrogenic sodium channels (ENaC) represent the third mechanism of sodium absorption and are important in the large intestine. ENaC are important targets of the renin–angiotensin– aldosterone system that regulates blood pressure and fluid balance.

Apart from these mechanisms, a cell electric potential that is 30–40 mV negative relative to the lumen provides an additional driving force for the coupled movement of Na+ with solutes such as amino acids, oligopeptides and bile acids through a separate set of transporters (Field, 2003). In the avian caecum, naturally occurring volatile fatty acids such as acetate and butyrate act as substrates for energy dependent sodium transport (Grubb, 1991a), indicating efficient and segment-specific ion transport. The lower intestine (colon and coprodeum) of the domestic fowl represents a special intestinal segment that can be considered as serving a reserve function. Under demanding conditions, such as a low salt diet, the colon and the coprodeum undergo both morphological changes, such as an increase in surface area, and functional changes, such as the greater expression of the electrogenic sodium channels (Laverty et al., 2001, Elbrond et al., 2004, Laverty et al., 2006).

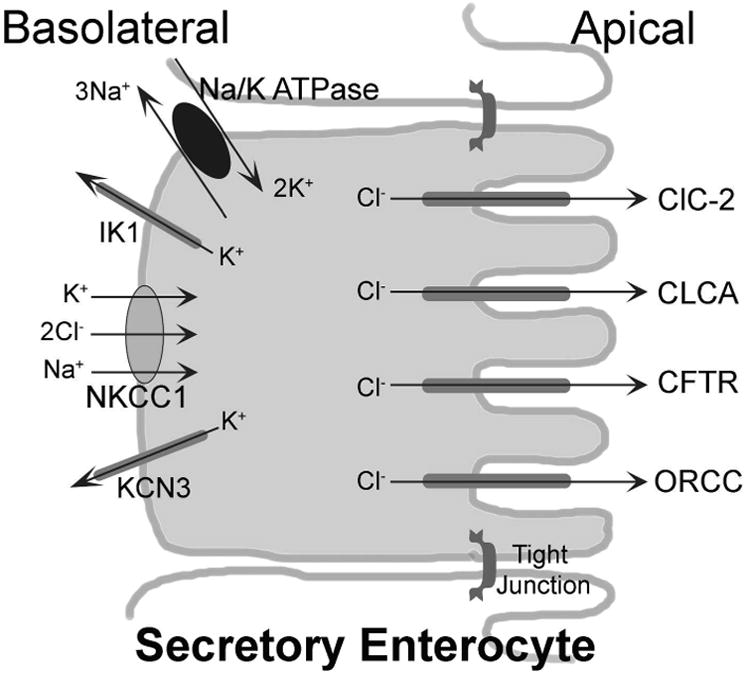

From a secretion point of view, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is the major chloride channel present on the apical membrane (Figure 2). Genetic mutations in the CFTR are responsible for the notoriously serious human condition. The K+ extruding potassium channels on the basolateral membrane (IK1, calcium activated potassium channel; KCN3, voltage gated potassium channel) helps maintain an intracellular electronegative potential which also aids in the diffusion of chloride through the apical channels. Besides CFTR, several other chloride channels, such as the Ca+ activated chloride channel (CLCA), the outwardly rectifying chloride channel (ORCC) and the chloride channel ClC-2 are present on the apical membrane. However, these channels may have a relatively minor role in chloride secretion compared to the CFTR. In chicken colonocytes, the anion exchanger (Cl/HCO3-) and the Na+/HCO3− cotransporter, in association with the NHE, maintain ion homeostasis by efficiently exchanging Na+, Cl−, H+, and HCO3− (Calonge and Ilundain, 1998).

Figure 2. Basic ion secretion mechanisms in intestinal epithelial cells. The Cl− secretion is maintained through co-ordination between K+ channels and NKCC1 on basolateral side and CFTR on apical side.

It is important to mention here that several of these ion transport mechanisms are not well characterised in the avian intestine. For example, though the expression and activity of the CFTR Cl− channel has been demonstrated in the renal proximal tubule of chickens (Laverty et al., 2012), its identity in the chicken intestine has not yet been clearly established. Besides cellular and molecular biology techniques, many of the studies on intestinal ion transport are performed using the Ussing chambers, which mimic the intestinal in vivo transport function but in an ex vivo experimental setting. This technique utilises measurement of the short-circuit current as an indicator of net ion transport across an epithelium such as gut mucosa and measurement of the flux of paracellular inert probes such as mannitol or inulin as an indicator of epithelial paracellular permeability (Grubb, 1991b, Clarke, 2009).

Intestinal ion transport during development

In chickens, enterocyte proliferation is not strictly restricted to the crypts at hatching and the crypt-villus axis develops in the first five days after hatching (Uni et al., 2000). The villous transit time (time required for the migration of cells from the crypt to the tip of the villus) was found to be 72 hours after two days of hatching but 96 hours after two of weeks of age (Uni et al., 2000), indicating a rapid compartmentalisation of the intestinal mucosa immediately after the hatching. The Paneth cells residing in intestinal crypts of many mammals have an important role in cell renewal and immunity. Though existence of Paneth cells in the chicken intestine was not clear previously (Nile et al., 2004), a recent study based on ultrastructural examination and in-situ hybridisation for lysozyme cmRNA, demonstrated the presence of Paneth cells in chicken intestinal crypts (Wang et al., 2016). During late incubation and around hatching, the intestinal mucosa strategically prepares for digesting carbohydrate- and protein-rich exogenous food, and it has been shown that the mRNA expression and activity of SGLT-1 and Na+K+ATPase significantly increase during this period (Uni et al., 2003). Hitherto sterile, the chicken intestinal tract undergoes microbial colonisation immediately after hatching and the quality of such microbial colonisation can have an enormous impact on intestinal health and growth. Besides affecting growth and intestinal microbial composition (Nakphaichit et al., 2011), colonisation pattern and initial exposure to varied bacterial communities can also affect ion transport related gene expression in the chicken gut (Yin et al., 2010).

Effect of feed and feed additives on intestinal ion transport

Intestinal epithelial ion transport adapts remarkably to changes in the diet. Hens maintained on a low-NaCl diet for more than three-weeks have been shown to not only increase transepithelial sodium transport but also acquire a 100% increase in microvillus surface area with relatively greater numbers of open sodium channels in the cell membranes of the lower intestine (Sodring Elbrond et al., 1991). A low sodium diet increases Na+/H+ exchange in the chicken ileum and colon due to an increase in the expression and activity of the NHE2 transporter isoform (Donowitz et al., 1998). Contrarily, SGLT-1 expression decreases within two days of feeding a modified low sodium diet. It has been suggested that while activity of the apical NHE2 transporter in the ileum and the colon is regulated by aldosterone that of SGLT-1 is regulated by arginine vasotocin (De La Horra et al., 2001). Low dietary sodium is known to reduce the activity and sodium affinity of the Na+K+-ATPase located on the basolateral membrane (Gal-Garber et al., 2003). Dietary protein composition has been shown to influence the mRNA abundance of PepT1 (a peptide transporter 1), amino acid (AA) transporters and aminopeptidase N in the small intestine of the chicken (Gilbert et al., 2010). A reduction in the phosphorus content of the diet given to chickens from hatching till four days of age has been shown to significantly induce the mRNA expression of the sodium-phosphate Na-Pi cotransporter in the small intestine (Yan et al., 2007). Further, while dietary addition of phytate has been shown to hamper carbohydrase activity and overall digestive competence, the inclusion of phytase in the diet reversed these phytate-induced effects and led to an increase in the expression of amylase, brush border enzymes sucrase and maltase, and Na+K+-ATPase (Liu et al., 2008). The dietary supplementation of a probiotic Lactobacillus spp. can positively modify the architecture of the intestinal mucosal surface, and basal and glucose stimulated ion transport (Awad et al., 2010). Although numerous studies have demonstrated that an inclusion of dietary probiotics positively affects growth, intestinal morphology, immunity and resistance to intestinal pathogenic organisms (Patterson and Burkholder, 2003, Ashraf et al., 2013, Bai et al., 2013, Cao et al., 2013, Lei et al., 2013), the effects of probiotics on avian intestinal ion transport remain largely undefined and thus warrant further studies. This is particularly important as pre- and probiotics are being increasingly added to poultry feed for the maintenance of gut health.

Intestinal ion transport and microbial infections

Gastrointestinal infections are the outcome of the interplay between various pathogen virulence factors and host defence mechanisms that can result in altered gut transport or impaired barrier function, both of which can manifest clinical symptoms such as diarrhoea. Intestinal ion transport is critical for maintaining homeostasis of the luminal microbial population as studies have shown that the loss of ion transporters such as the CFTR and the NHEs can cause dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation (Norkina et al., 2004, Larmonier et al., 2013). Microbial infections affect intestinal ion transport, resulting in either hypersecretion or malabsorption, and utilize multiple pathways for the same. Many microbial agents are known to directly interact with individual intestinal ion transporters to either increase or decrease their activity and affect their presence on the apical membrane of the epithelial cells. Pathogenic microbial agents interact with TJs and the surrounding actin cytoskeleton to diminish intestinal barrier function. The loss of intestinal barrier function allows luminal antigens an increased access to the immune cells in lamina propria, which further activate the inflammatory cascade and exacerbate the diarrhoea. The inflammatory cytokines produced by the epithelial cells and the cells of the lamina propria are known to enhance intestinal secretion (Chang et al., 1990). The effects of common microbial infections on avian intestinal ion transport are presented below.

Escherichia coli

In mammals, diarrhoea-causing Escherichia coli are grouped mainly as enteropathogenic (EPEC), enterohaemorrhagic (EHEC), enteroaggregative (EAEC), enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroinvasive, and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC) (Hodges and Gill, 2010). Most of the resident intestinal E. coli organisms of poultry are non-pathogenic and enteritis caused by them is rather uncommon compared to extra-intestinal diseases caused by the avian pathogenic variety (APEC). Nonetheless, E. coli serogroup O78, which is common in poultry, is classified as ETEC and its infections are characterised by an increase in intestinal fluid secretion mediated by colonisation factors and enterotoxins. Both ETEC heat labile and heat stable toxins elicit chloride secretion but utilise different second messengers; the heat labile toxins activate cAMP while the heat stable toxins activate cGMP (Field, 2003). A recent in vitro study has shown that both APEC IMT4529 (O24:H4) and a control avian non-pathogenic E. coli IMT11322 (Ont:H16) decrease chicken jejunal permeability (conductance) (Awad et al., 2014) prompting the conclusion that contact with E. coli alone was sufficient for the intestinal epithelium to immediately tighten the paracellular TJ barrier. However, in the same study, pathogenic E. coli increased ion secretion in the chicken jejunum in cAMP/PKA-dependent response to the cholera toxin which is a secretagogue. Further studies are warranted to examine if the APEC and ETEC have differential effects on intestinal ion transport and barrier function and if such differences form the basis for disease manifestation.

Salmonella spp

Elaborate studies show that the interaction between Salmonella spp. and the intestinal mucosa is a complex process where subsets of virulence genes influence distinct aspects of pathogenesis, including its effects on intestinal ion transport. By means of a needle and syringe-like type III secretory system (TTSS-1) virulence factors such as the Salmonella spp. pathogenicity island-1 (SPI-1), Outer Proteins (Sop) and the Invasion Protein (Sip) are delivered into the intestinal epithelial cells (Wallis and Galyov, 2000). Given the extensive alterations in the ion transport caused by the inflammatory response to salmonellosis, it has been a challenge for researchers to deduce its primary effects on intestinal ion transport using a relevant experimental model. One such study using human intestinal xenografts in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice revealed that an infection with Salmonella typhimurium rapidly increases both basal and Ca2+- and cAMP-stimulated ion transport in a cyclooxygenase (COX-2)-mediated and prostaglandin PGE2 -dependent manner (Bertelsen et al., 2003). It has been suggested that SopB-dependent increase in Inositol-1,4,5,6-tetraphosphate levels can antagonise the closure of chloride channels in salmonella-infected cells, thus leading to excessive fluid secretion (Eckmann et al., 1997, Norris et al., 1998, Wallis and Galyov, 2000). Inositol phosphates (IPs) represent a family of membrane molecules that act as second messengers and regulate a wide array of cellular functions. Salmonella-infected epithelial cells are known to release chemoattractants that stimulate the transepithelial migration of neutrophils through TJs into the paracellular spaces causing further fluid loss (Wallis and Galyov, 2000). Such inflammatory responses may result in extrusion of the infected cells from the epithelial lining which would then lead to blunting of the villi and loss of absorptive surface. A recent in vitro study using Salmonella enteritidis, which causes an asymptomatic salmonella infection in chicken, showed that conductance (permeability) of the intestinal epithelium and intestinal ion transport were both reduced upon application of either living bacteria or the salmonella endotoxin to the intestinal mucosa (Awad et al., 2012). The authors postulated that this effect was consistent with the absence of diarrhoea during salmonellosis in the chicken.

Clostridia spp

Necrotic enteritis (NE) is an important enteric disease in poultry that is caused by Clostridium perfringens (types A and C). Predisposing conditions such as coccidiosis, ascaridiasis or salmonellosis infections are associated with clostridia overgrowth and toxin production that cause severe mucosal damage and elicit a strong host inflammatory response. A report on the effects of the application of a purified C. perfringens α toxin indicated that the toxin induced a secretory response when applied on the serosal side, but that it inhibited sodium-glucose co-transport on the mucosal side of isolated jejunal mucosa of laying hens (Rehman et al., 2006). However, the mucosal application of the α toxin did not change the electrophysiological response, indicating that the impairment of apical TJ barrier may be necessary in order for the clostridia toxin to exert its effects on the basolateral side. In fact, the C. perfringens enterotoxin has been shown to interact with at least two TJ proteins, namely occludin and claudin, both of which are critical for maintaining the integrity of the TJ barrier (Sonoda et al., 1999, Singh et al., 2000). The C. botulinum C2 toxin has been shown to increase fluid secretion in intestinal loops and cause necrosis of the intestinal mucosa in chickens and pheasants (Kurazono et al., 1987). The C. difficile toxin B can cause translocation of the apical NHE3 transporter to the sub-apical endomembrane compartment which leads to Na+ malabsorption, and it is possible that the toxin can inactivate the Rho-family GTPases and affect interactions NHE3 with the actin cytoskeleton (Hayashi et al., 2004). Thus, it is possible that initial effect of the clostridia toxins on intestinal ion transport and TJ barrier may lead to the loss of intestinal epithelial homeostasis and ultimately cause the massive cell destruction and necrosis seen during NE.

Rotavirus

Rotavirus has been implicated as the causal organism of diarrhoea in chicken, turkey and several other avian species (Day et al., 2007, Pantin-Jackwood et al., 2007). Infections can occur in any age group, can be subclinical or clinical, and cause morbidity and diarrhoea (McNulty et al., 1978). Recent studies attribute most of the effects of a rotavirus infection on intestinal ion transport to a viral enterotoxin which is a non-structural protein named NSP4. Though the diarrhoeagenic effects of the rotavirus NSP4 have not been directly studied in the avian intestine, a specific antigenic site (AS II, residues 136 to 150) has been shown to be conserved among a variety of mammalian and avian rotaviruses (Borgan et al., 2003) and the avian rotavirus NSP4 glycoproteins are known to be enterotoxic to suckling mice (Mori et al., 2002).

Astrovirus

Astroviruses cause morbidity and enteric infections in a number of mammalian hosts (Grohmann et al., 1993, Glass et al., 1996, Koci et al., 2003) and are known to be widely prevalent in commercial chicken and turkey flocks (Reynolds and Saif, 1986, Reynolds et al., 1987, Baxendale and Mebatsion, 2004). Diarrhoea, retarded growth and altered intestinal maltase activity with minimal histologic changes have been described in the intestine of astrovirus-infected juvenile turkeys (Thouvenelle et al., 1995). The Turkey astrovirus, TAstV-2, originally isolated from natural outbreaks of complex diarrheal diseases involving multiple organisms, has been reported to cause experimental diarrhoea even in the absence of overt histological changes and enterocyte death (Koci et al., 2003). In studies, TAstV-2 infection reduced the transport of Na+ by redistribution of the apical NHE3 (Na+-H+ exchanger) from the membrane to the cytosol which was, in turn, associated with a rearrangement of the F-actin filaments (Nighot et al., 2010). As opposed to secretory diarrhoea due to excessive Cl– efflux, impaired Na+ absorption causes malabsorptive diarrhoea as the retention of Na+ in the lumen results in a reduction in the ion gradient required for efficient water absorption. The role of autocrine and paracrine cytokines is also important for maintaining intestinal homeostasis. For example, an increase in TGF-β activity, which preserves epithelial barrier function and dampens the cAMP-mediated Cl– secretory response (Howe et al., 2002), has been reported to occur within 24 hours of TAstV-2 infection and it remains elevated till 12 days post infection in turkey poults (Koci et al., 2003).

Other microbial infections

Asymptomatic infections can affect intestinal ion transport and compromise production efficiency in poultry. One such example is infection with Campylobacter jejuni, which has been shown to reduce the intestinal absorptive surface area, alter ion transport and reduce intestinal epithelial barrier function in chickens (Awad et al., 2015). The effects of protozoan infections on intestinal ion transport in poultry is largely unknown but studies in other species and laboratory animals indicate that protozoan infections can profoundly affect intestinal ion transport. For instance, chronic cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised mice has been shown to decrease net ileal ion transport, weaken the paracellular barrier and impair Na+-glucose cotransport (Kapel et al., 1997). During experimental infections with Eimeria separata in the rat, sodium absorption in the infected region of the proximal colon was impaired but a compensatory increase in sodium absorption was observed in the non-infected distal colon through the aldosterone-regulated ENaC channel (Cirak et al., 2004). Severe infection with Spironucleus spp. in farmed pheasants and partridges has been shown to reduce intestinal ion absorption by more than half when compared to healthy birds (Lloyd et al., 2005). Among mycotoxins, an acute exposure to aflatoxin AFB1 has been shown to increase apical anion secretion in the jejunal epithelium of chickens with minimal effects on active glucose uptake (Yunus et al., 2010). Various trichothecenes such as DON, NIV and 15-Ac-DON have been shown to be capable of reducing SGLT activity (Awad et al., 2004, Awad et al., 2005, Awad et al., 2007, Awad et al., 2008).

Adaptation of avian intestinal ion transport to nutritional and environmental alterations

There is substantial evidence that ion transport in the avian intestine adapts to nutritional or environmental changes. For example, dehydration results in an increase in sodium-hydrogen exchange, albeit with segmental differences; NHE2 activity increases in the ileum and the colon, while in the jejunum, the activity of both NHE2 and NHE3 increases. Dehydration also leads to an increase in serum aldosterone levels and sodium glucose co-transport in all intestinal segments (De la Horra et al., 1998). Another example of intestinal adaptation is an increase in the intestinal uptake of Ca2+ and calcium binding protein after restricted feeding during moulting in hens (Berry and Brake, 1991, al-Batshan et al., 1994). Pharmacologic stress, due to the administration of corticosterone, has been shown to result in a compensatory increase in intestinal absorptive function, i.e., an increase in the relative abundance of SGLT-1, vitamin D-dependent calcium-binding protein-28,000 molecular weight (CaBP-D28k), peptide transporter 1 (PepT-1) and the liver fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP) (Hu et al., 2010).

Adaptation of fast growing broilers to the exposure of ambient heat is an important matter for commercial poultry production. Broiler chicken exposed to warm temperatures (30°C) have been shown to exhibit an approximately 50% increase in the expression and activity of SGLT-1 in the jejunum. This is thought to be an adaptive response to heat because even though birds exposed to warm temperatures displayed reduced feed intake, pair-fed control birds (birds maintained at thermo-neutral temperature (20°C) but offered feed equal in amount to that consumed by warm temperature birds) did not exhibit such changes in the expression or activity of SGLT-1(Garriga et al., 2006). Heat exposure reduced the gene expression of glucose transporter 2 (GLUT-2) which diffuses monosaccharides from the basolateral side of intestinal epithelial cells into the extracellular fluid, fatty acid binding protein FABP1, and fatty acid receptor CD36 in broiler chicken (Sun et al., 2015). The serum electrolyte and acid-base imbalances seen in broiler chicken exposed to heat are thought to be mediated by reduced activity of Na+K+ATPase, Mg2+-activated ATPase, and Na+-ATPase in the intestine and kidney (Chen et al., 1994). While ion transport and digestive activity is optimised to a certain degree in the face of reduced feed intake and decreased absorptive compartment (decreased intestinal surface area) caused by the heat exposure (Mitchell and Carlisle, 1992), the threshold of physiological responses under such conditions requires further investigation.

Conclusions

The current understanding of ion transport in the avian intestine is inadequate. Advances in scientific instrumentations, availability of reagents specific to ion channel studies and better genetic and pharmacologic experimental approaches will continue to improve our understanding of ion transport in the avian intestine. Available information suggests that the intestinal ion transport is efficiently adapted to alterations in nutrition and environment. However, the threshold of such adaptation should be critically considered and aligned with the management and production goals. Ion transporters have been studied as targets for the mitigation of defects in intestinal fluid homeostasis due to both infective and non-infective processes. For instance, the chloride channel CFTR inhibitors thiazolidinone (Ma et al., 2002) and glycine hydrazide (GlyH) (Sonawane et al., 2007) have been shown to block cholera toxin-induced small intestinal fluid secretion in experimental mice models. Zinc is considered to be an antidiarrhoeal agent that inhibits cAMP-stimulated Cl− secretion by blocking the basolateral K-channel (Hoque et al., 2005, Sandle, 2011). Removal of antibiotics from animal feed, the use of feed alternatives such as pre- and probiotics and phytonutrients, hyperimmune antibodies, bacteriophages, antimicrobial peptides and toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists are all being investigated for potential use in animal feed for the maintenance of host health (Lillehoj and Lee, 2012). Nonetheless, the effects of using such disease-mitigating agents on intestinal ion transport merit further research and investigation. Better understanding of intestinal ion transport in poultry will help in the development of scientific strategies to maximise their gut health, welfare, and ultimately, production.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Fred Hoerr, Auburn, Alabama for invaluable inputs on this manuscript.

References

- Al-Batshan HA, Scheideler SE, Black BL, Garlich JD, Anderson KE. Duodenal calcium uptake, femur ash, and eggshell quality decline with age and increase following molt. Poultry science. 1994;73:1590–1596. doi: 10.3382/ps.0731590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf S, Zaneb H, Yousaf MS, Ijaz A, Sohail MU, Muti S, Usman MM, Ijaz S, Rehman H. Effect of dietary supplementation of prebiotics and probiotics on intestinal microarchitecture in broilers reared under cyclic heat stress. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 2013;97 Suppl 1:68–73. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Aschenbach JR, Khayal B, Hess C, Hess M. Intestinal epithelial responses to salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis: Effects on intestinal permeability and ion transport. Poultry science. 2012;91:2949–2957. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Aschenbach JR, Setyabudi FM, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Bohm J, Zentek J. In vitro effects of deoxynivalenol on small intestinal d-glucose uptake and absorption of deoxynivalenol across the isolated jejunal epithelium of laying hens. Poultry science. 2007;86:15–20. doi: 10.1093/ps/86.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Bohm J, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Hulan HW, Zentek J. Effects of deoxynivalenol on general performance and electrophysiological properties of intestinal mucosa of broiler chickens. Poultry science. 2004;83:1964–1972. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.12.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Ghareeb K, Bohm J. Effect of addition of a probiotic micro-organism to broiler diet on intestinal mucosal architecture and electrophysiological parameters. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 2010;94:486–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2009.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Hess C, Khayal B, Aschenbach JR, Hess M. In vitro exposure to escherichia coli decreases ion conductance in the jejunal epithelium of broiler chickens. PloS one. 2014;9:e92156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Molnar A, Aschenbach JR, Ghareeb K, Khayal B, Hess C, LIEBHART D, DUBLECZ K, HESS M. Campylobacter infection in chickens modulates the intestinal epithelial barrier function. Innate immunity. 2015;21:151–160. doi: 10.1177/1753425914521648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Bohm J, Zentek J. Effects of b-trichothecenes on luminal glucose transport across the isolated jejunal epithelium of broiler chickens. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 2008;92:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2007.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad WA, Rehman H, Bohm J, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Zentek J. Effects of luminal deoxynivalenol and l-proline on electrophysiological parameters in the jejunums of laying hens. Poultry science. 2005;84:928–932. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.6.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai SP, Wu AM, Ding XM, Lei Y, Bai J, Zhang KY, Chio JS. Effects of probiotic-supplemented diets on growth performance and intestinal immune characteristics of broiler chickens. Poultry science. 2013;92:663–670. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxendale W, Mebatsion T. The isolation and characterisation of astroviruses from chickens. Avian pathology. 2004;33:364–370. doi: 10.1080/0307945042000220426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry W, Brake J. Modulation of calbindin-d28k in avian egg shell gland and duodenum. Poult Sci. 1991;70:655–657. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen LS, Paesold G, Eckmann L, Barrett KE. Salmonella infection induces a hypersecretory phenotype in human intestinal xenografts by inducing cyclooxygenase 2. Infection and immunity. 2003;71:2102–2109. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.2102-2109.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgan MA, Mori Y, Ito N, Sugiyama M, Minamoto N. Antigenic analysis of nonstructural protein (nsp) 4 of group a avian rotavirus strain po-13. Microbiology and immunology. 2003;47:661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calonge ML, Ilundain AA. Hco3(-)-dependent ion transport systems and intracellular ph regulation in colonocytes from the chick. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1998;1371:232–240. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao GT, Zeng XF, Chen AG, Zhou L, Zhang L, Xiao YP, Yang CM. Effects of a probiotic, enterococcus faecium, on growth performance, intestinal morphology, immune response, and cecal microflora in broiler chickens challenged with escherichia coli k88. Poultry science. 2013;92:2949–2955. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EB, Musch MW, Mayer L. Interleukins 1 and 3 stimulate anion secretion in chicken intestine. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1518–1524. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91084-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Sangiah S, Chen H, Roder JD, Shen Y. Effects of heat stress on na+,k(+)-atpase, mg(2+)-activated atpase, and na(+)-atpase activities of broiler chickens vital organs. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. 1994;41:345–356. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SH, Chung TK, Yu B. Effects of supplemental 25-hydroxycholecalciferol on growth performance, small intestinal morphology, and immune response of broiler chickens. Poultry science. 2009;88:2333–2341. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirak VY, Kowalik S, Burger HJ, Zahner H, Clauss W. Effects of eimeria separata infections on na+ and cl- transport in the rat large intestine. Parasitology research. 2004;92:490–495. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke LL. A guide to ussing chamber studies of mouse intestine. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2009;296:G1151–G1166. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90649.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JM, Spackman E, Pantin-Jackwood M. A multiplex rt-pcr test for the differential identification of turkey astrovirus type 1, turkey astrovirus type 2, chicken astrovirus, avian nephritis virus, and avian rotavirus. Avian Diseases. 2007;51:681–684. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086(2007)51[681:AMRTFT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Horra MC, Calonge ML, Ilundain AA. Effect of dehydration on apical na+-h+ exchange activity and na+-dependent sugar transport in brush-border membrane vesicles isolated from chick intestine. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 1998;436:112–116. doi: 10.1007/s004240050611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Horra MC, Cano M, Peral MJ, Calonge ML, Ilundain AA. Hormonal regulation of chicken intestinal nhe and sglt-1 activities. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2001;280:R655–660. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.3.R655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donowitz M, De La Horra C, Calonge ML, Wood IS, Dyer J, Gribble SM, De Medina FS, Tse CM, Shirazi-Beechey SP, Ilundain AA. In birds, nhe2 is major brush-border na+/h+ exchanger in colon and is increased by a low-nacl diet. The American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:R1659–1669. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.6.R1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann L, Rudolf MT, Ptasznik A, Schultz C, Jiang T, Wolfson N, Tsien R, Fierer J, Shears SB, Kagnoff MF, Traynor-Kaplan AE. D-myo-inositol 1,4,5,6-tetrakisphosphate produced in human intestinal epithelial cells in response to salmonella invasion inhibits phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:14456–14460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbrond VS, Jones CJ, Skadhauge E. Localisation, morphology and function of the mitochondria-rich cells in relation to transepithelial na(+)-transport in chicken lower intestine (coprodeum) Comparative biochemistry and physiology Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology. 2004;137:683–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M. Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;111:931–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI18326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal-Garber O, Mabjeesh SJ, Sklan D, Uni Z. Nutrient transport in the small intestine: Na+,k+-atpase expression and activity in the small intestine of the chicken as influenced by dietary sodium. Poultry science. 2003;82:1127–1133. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.7.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriga C, Hunter RR, Amat C, Planas JM, Mitchell MA, Moreto M. Heat stress increases apical glucose transport in the chicken jejunum. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2006;290:R195–201. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00393.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ER, Li H, Emmerson DA, Webb KE, Jr, Wong EA. Dietary protein composition influences abundance of peptide and amino acid transporter messenger ribonucleic acid in the small intestine of 2 lines of broiler chicks. Poultry science. 2010;89:1663–1676. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass RI, Noel J, Mitchell D, Herrmann JE, Blacklow NR, Pickering LK, Dennehy P, Ruiz-Palacios G, De Guerrero ML, Monroe SS. The changing epidemiology of astrovirus-associated gastroenteritis: A review. Archives of virology Supplementum. 1996;12:287–300. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann GS, Glass RI, Pereira HG, Monroe SS, Hightower AW, Weber R, Bryan RT. Enteric viruses and diarrhea in hiv-infected patients. Enteric opportunistic infections working group. The New England journal of medicine. 1993;329:14–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307013290103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb BR. Avian cecum: Role of glucose and volatile fatty acids in transepithelial ion transport. The American Journal of Physiology. 1991a;260:G703–710. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.5.G703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb BR. Ion transport across the chick ileum: A good model for transport studies. Comparative biochemistry and physiology A, Comparative physiology. 1991b;100:753–757. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(91)90403-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Szaszi K, Coady-Osberg N, Furuya W, Bretscher AP, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. Inhibition and redistribution of nhe3, the apical na+/h+ exchanger, by clostridium difficile toxin b. The Journal of general physiology. 2004;123:491–504. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges K, Gill R. Infectious diarrhea: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Gut microbes. 2010;1:4–21. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.1.11036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque KM, Rajendran VM, Binder HJ. Zinc inhibits camp-stimulated cl secretion via basolateral k-channel blockade in rat ileum. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2005;288:G956–963. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00441.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K, Gauldie J, Mckay DM. Tgf-beta effects on epithelial ion transport and barrier: Reduced cl- secretion blocked by a p38 mapk inhibitor. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2002;283:C1667–1674. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00414.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XF, Guo YM, Huang BY, Bun S, Zhang LB, Li JH, Liu D, Long FY, Yang X, Jiao P. The effect of glucagon-like peptide 2 injection on performance, small intestinal morphology, and nutrient transporter expression of stressed broiler chickens. Poultry science. 2010;89:1967–1974. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapel N, Huneau JF, Magne D, Tome D, Gobert JG. Cryptosporidiosis-induced impairment of ion transport and na+-glucose absorption in adult immunocompromised mice. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1997;176:834–837. doi: 10.1086/517316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koci MD, Moser LA, Kelley LA, Larsen D, Brown CC, Schultz-Cherry S. Astrovirus induces diarrhea in the absence of inflammation and cell death. Journal of virology. 2003;77:11798–11808. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11798-11808.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurazono H, Hosokawa M, Matsuda H, Sakaguchi G. Fluid accumulation in the ligated intestinal loop and histopathological changes of the intestinal mucosa caused by clostridium botulinum c2 toxin in the pheasant and chicken. Research in veterinary science. 1987;42:349–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larmonier CB, Laubitz D, Hill FM, Shehab KW, Lipinski L, Midura-Kiela MT, Mcfadden RM, Ramalingam R, Hassan KA, Golebiewski M, Besselsen DG, Ghishan FK, Kiela PR. Reduced colonic microbial diversity is associated with colitis in nhe3-deficient mice. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2013;305:G667–677. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00189.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty G, Anttila A, Carty J, Reddy V, Yum J, Arnason SS. Cftr mediated chloride secretion in the avian renal proximal tubule. Comparative biochemistry and physiology Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology. 2012;161:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty G, Bjarnadottir S, Elbrond VS, Arnason SS. Aldosterone suppresses expression of an avian colonic sodium-glucose cotransporter. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2001;281:R1041–1050. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.4.R1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty G, Elbrond VS, Arnason SS, Skadhauge E. Endocrine regulation of ion transport in the avian lower intestine. General and comparative endocrinology. 2006;147:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson S, Namkung H, Antongiovanni M, Lee EH. Effect of butyric acid on the performance and carcass yield of broiler chickens. Poultry science. 2005;84:1418–1422. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.9.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei K, Li YL, Yu DY, Rajput IR, Li WF. Influence of dietary inclusion of bacillus licheniformis on laying performance, egg quality, antioxidant enzyme activities, and intestinal barrier function of laying hens. Poultry science. 2013;92:2389–2395. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj HS, Lee KW. Immune modulation of innate immunity as alternatives-to-antibiotics strategies to mitigate the use of drugs in poultry production. Poultry science. 2012;91:1286–1291. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Ru YJ, Li FD, Cowieson AJ. Journal of animal science. 2008;86:3432–3439. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S, Irvine KL, Eves SM, Gibson JS. Fluid absorption in the small intestine of healthy game birds and those infected with spironucleus spp. Avian pathology. 2005;34:252–257. doi: 10.1080/03079450500112179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Thiagarajah JR, Yang H, Sonawane ND, Folli C, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Thiazolidinone cftr inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002;110:1651–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI16112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcnulty MS, Allan GM, Stuart JC. Rotavirus infection in avian species. The Veterinary record. 1978;103:319–320. doi: 10.1136/vr.103.14.319-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MA, Carlisle AJ. The effects of chronic exposure to elevated environmental temperature on intestinal morphology and nutrient absorption in the domestic fowl (gallus domesticus) Comparative biochemistry and physiology A, Comparative physiology. 1992;101:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(92)90641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y, Borgan MA, Ito N, Sugiyama M, Minamoto N. Diarrhea-inducing activity of avian rotavirus nsp4 glycoproteins, which differ greatly from mammalian rotavirus nsp4 glycoproteins in deduced amino acid sequence in suckling mice. Journal of virology. 2002;76:5829–5834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5829-5834.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakphaichit M, Thanomwongwattana S, Phraephaisarn C, Sakamoto N, Keawsompong S, Nakayama J, Nitisinprasert S. The effect of including lactobacillus reuteri kub-ac5 during post-hatch feeding on the growth and ileum microbiota of broiler chickens. Poultry science. 2011;90:2753–2765. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrin M, Siddiqi M, Masum M, Wares M. Gross and histological studies of digestive tract of broilers during postnatal growth and development. Journal of the Bangladesh Agricultural University. 2012;10:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nighot PK, Moeser A, Ali RA, Blikslager AT, Koci MD. Astrovirus infection induces sodium malabsorption and redistributes sodium hydrogen exchanger expression. Virology. 2010;401:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nile CJ, Townes CL, Michailidis G, Hirst BH, Hall J. Identification of chicken lysozyme g2 and its expression in the intestine. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2004;61:2760–2766. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4345-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkina O, Burnett TG, De Lisle RC. Bacterial overgrowth in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator null mouse small intestine. Infection and immunity. 2004;72:6040–6049. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6040-6049.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FA, Wilson MP, Wallis TS, Galyov EE, Majerus PW. Sopb, a protein required for virulence of salmonella dublin, is an inositol phosphate phosphatase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:14057–14059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda AK, Rama Rao SV, Raju MV, Shyam Sunder G. Effect of butyric acid on performance, gastrointestinal tract health and carcass characteristics in broiler chickens. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2009;22:1026. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Spackman E, Day JM, Rives D. Periodic monitoring of commercial turkeys for enteric viruses indicates continuous presence of astrovirus and rotavirus on the farms. Avian Diseases. 2007;51:674–680. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086(2007)51[674:PMOCTF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JA, Burkholder KM. Application of prebiotics and probiotics in poultry production. Poultry science. 2003;82:627–631. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky DK. Healing the epithelium: Solving the problem from two sides. Journal of gastroenterology. 1997;32:122–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01213309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman H, Awad WA, Lindner I, Hess M, Zentek J. Clostridium perfringens alpha toxin affects electrophysiological properties of isolated jejunal mucosa of laying hens. Poultry science. 2006;85:1298–1302. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.7.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DL, Saif YM. Astrovirus: A cause of an enteric disease in turkey poults. Avian Diseases. 1986;30:728–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DL, Saif YM, Theil KW. Enteric viral infections of turkey poults: Incidence of infection. Avian Diseases. 1987;31:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandle GI. Infective and inflammatory diarrhoea: Mechanisms and opportunities for novel therapies. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2011;11:634–639. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh U, Van Itallie CM, Mitic LL, Anderson JM, Mcclane BA. Caco-2 cells treated with clostridium perfringens enterotoxin form multiple large complex species, one of which contains the tight junction protein occludin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:18407–18417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodring Elbrond V, Dantzer V, Mayhew TM, Skadhauge E. Avian lower intestine adapts to dietary salt (nacl) depletion by increasing transepithelial sodium transport and microvillous membrane surface area. Experimental physiology. 1991;76:733–744. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1991.sp003540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane ND, Zhao D, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Lectin conjugates as potent, nonabsorbable cftr inhibitors for reducing intestinal fluid secretion in cholera. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1234–1244. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda N, Furuse M, Sasaki H, Yonemura S, Katahira J, Horiguchi Y, Tsukita S. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin fragment removes specific claudins from tight junction strands: Evidence for direct involvement of claudins in tight junction barrier. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;147:195–204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Zhang H, Sheikhahmadi A, Wang Y, Jiao H, Lin H, Song Z. Effects of heat stress on the gene expression of nutrient transporters in the jejunum of broiler chickens (gallus gallus domesticus) International journal of biometeorology. 2015;59:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00484-014-0829-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thouvenelle ML, Haynes JS, Sell JL, Reynolds DL. Astrovirus infection in hatchling turkeys: Alterations in intestinal maltase activity. Avian Diseases. 1995;39:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uni Z, Geyra A, Ben-hur H, Sklan D. Small intestinal development in the young chick: Crypt formation and enterocyte proliferation and migration. British poultry science. 2000;41:544–551. doi: 10.1080/00071660020009054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uni Z, Tako E, Gal-Garber O, Sklan D. Morphological, molecular, and functional changes in the chicken small intestine of the late-term embryo. Poultry science. 2003;82:1747–1754. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.11.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis TS, Galyov EE. Molecular basis of salmonella-induced enteritis. Molecular microbiology. 2000;36:997–1005. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Li J, Li J, Jr, Li RX, Lv CF, Li S, Mi YL, Zhang CQ. Identification of the paneth cells in chicken small intestine. Poultry science. 2016;95:1631–1635. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Angel R, Ashwell CM. Characterisation of the chicken small intestine type iib sodium phosphate cotransporter. Poultry science. 2007;86:67–76. doi: 10.1093/ps/86.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Lei F, Zhu L, Li S, Wu Z, Zhang R, Gao GF, Zhu B, Wang X. Exposure of different bacterial inocula to newborn chicken affects gut microbiota development and ileum gene expression. The International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal. 2010;4:367–376. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunus AW, Awad WA, Kroger S, Zentek J, Bohm J. In vitro aflatoxin b(1) exposure decreases response to carbamylcholine in the jejunal epithelium of broilers. Poultry science. 2010;89:1372–1378. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]