Abstract

Background

In 2014, 15 500 persons in Germany were given the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma. This disease is the third most common cancer of the urogenital system. The mean age at diagnosis is 68 years in men and 71 in women.

Methods

Pertinent publications up to 2014 were retrieved by a systematic literature search and reviewed in a moderated, formalized consensus process. Key questions were generated and answered by the adaptation of existing international guidelines, on the basis of an independent literature review, and by expert consensus. Representatives of 30 medical specialty societies, patient self-help groups, and other organizations participated in the process.

Results

The search for guidelines yielded 80 hits, 23 of which were judged by DELBI to be potentially relevant; 7 were chosen for adaptation. Smoking, obesity, and hypertension increase the risk of renal cell carcinoma. Its 5-year survival rate is 75% for men and 77% for women. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for 2.6% of all deaths from cancer in men and 2.1% in women. Nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy are the standard treatments. Locally confined tumors in clinical stage T1 should be treated with kidney-preserving surgery. Minimally invasive surgery is often possible as long as the surgeon has the requisite experience. For patients with metastases, overall and progression-free survival can be prolonged with VEGF and mTOR inhibitors. The resection or irradiation of metastases can be a useful palliative treatment for patients with brain metastases or osseous metastases that are painful or increase the risk of fracture.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive surgery and new systemic drugs have expanded the therapeutic options for patients with renal cell carcinoma. The search for new predictive and prognostic markers is now in progress.

Renal tumors account for 3–4% of all malignant tumors in adults; 80–90% of these are renal cell carcinomas, which are unilateral in 97% of patients and bilateral in 3%. Roughly 15 500 patients were given the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma in Germany in 2014 (1). The disease affects men more often than women (63% vs. 37%); it is the 8th most common cancer in men and the 10th most common in women. The mean age at the time of diagnosis is 68 years in men and 71 in women (1).

The first S3 guideline on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of renal cell carcinoma was completed and published online in September 2015 (2). It was sponsored by the oncological guideline program of the German Cancer Aid Society, the German Cancer Society, and the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF). It was developed by representatives of 30 different specialty societies and expert groups under the leadership of the German Society for Urology (DGU) and the German Society for Hematology and Oncology (DGHO).

Methods

43 key questions were identified, of which 21 were answered by means of the adaptation of existing international guidelines and 12 on the basis of an independent literature review. The remaining questions were answered by expert consensus.

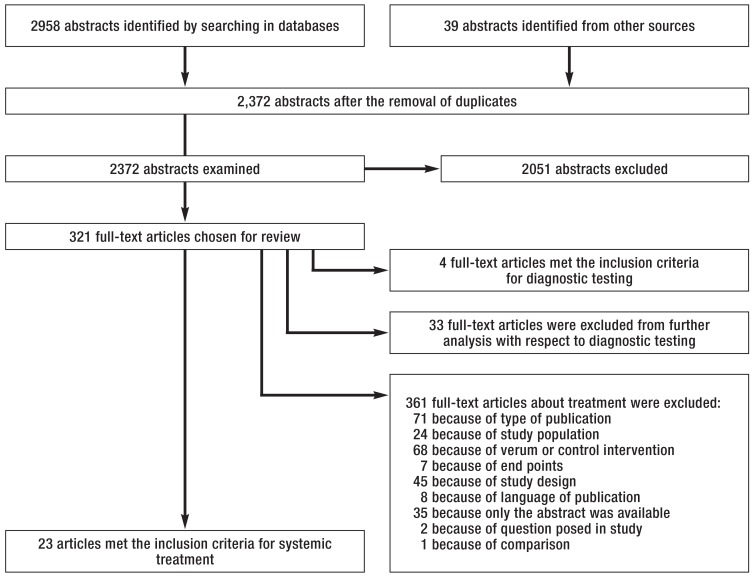

An initial search for existing international guidelines yielded 80 hits, 23 of which were judged by DELBI (3) to be potentially relevant; 7 were chosen for adaptation. Another 11 primary searches were conducted, 3 of them externally. The search strategies, results, and evidence tables can be found in the guideline report (4). The findings of the externally conducted literature search on the systemic treatment of renal cell carcinoma are shown in the eFigure.

eFigure.

Our literature searches identified a total of 2372 relevant abstracts. Among these publications, 321 were selected as full texts for further evaluation. Finally, 23 publications met the inclusion criteria defined a priori for the assessment of the relative efficacy and safety of systemic treatments

In the guideline, all evidence-based recommendations and statements were assigned an evidence level according to the system of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (eTable 1) (5). Recommendation strengths (grades) were also assigned and reported (eTable 2).

eTable 1. The SIGN classification of levels of evidence.

| Level of evidence | Description |

|---|---|

| 1++ | High quality meta-analyses. systematic reviews of RCTs. or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses. systematic reviews. or RCTs with a low risk of bias |

| 1− | Meta-analyses. systematic reviews. or RCTs with a high risk of bias |

| 2++ | High quality systematic reviews of case–control or cohort or studies High quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2+ | Well-conducted case–control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2− | Case–control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

| 3 | Non-analytic studies. e.g. case reports. case series |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

RCT. randomized controlled trial; SIGN. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

eTable 2. The recommendation grades used in this guideline.

| Recommendation grade | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Strong recommendation |

| B | Recommendation |

| 0 | Open recommendation |

Finally, 9 quality indicators were defined according to the methodology of the German Guideline Program in Oncology (GGPO), and agreed upon by consensus, for the implementation of the guideline and the measurement of its effect in practice (6). These quality indicators can be generated from future data in clinical cancer registries and will also be incorporated into the patient data questionnaires of all German uro-oncological centers.

Risk factors

Smoking, obesity, and high blood pressure increase the risk of renal cell carcinoma (7, 8) (level of evidence [LoE] 2++). It is estimated that smoking elevates the risk by 54% in men and by 22% in women; there is a clear dose–response relationship, with the highest risk among the heaviest smokers. In a cohort study that included 148 206 non-smokers, 138 332 current smokers, and 51 638 former smokers, the number of cases of renal cell carcinoma that developed in each group was 180, 334, and 145, respectively (8). The quantitative elevation of risk due to obesity was by approximately 24% for a 5 kg/m2 rise in the body mass index (BMI) in men, and 34% in women. In the cohort study mentioned above, there were approximately 45,000 persons in each of three weight groups (BMI <20.75, in the range 23.81–24.76, and >27.76); the number of cases of renal cell carcinoma in these weight groups was 32, 107, and 195, respectively (8).

Effective blood pressure control can lower the risk of renal cell carcinoma (LoE 2+). Patients with end-stage renal failure have a fourfold elevated risk of renal cell carcinoma (9) (LoE 2-). 5–10% of patients with renal cell carcinoma have a hereditary syndrome such as the von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (10). Patients suspected of having renal cell carcinoma on a hereditary basis should be offered genetic counseling (recommendation grade A).

Pathology

The histological subtypes of renal cell carcinoma differ in their origins and biological behavior. The subtype should be determined according to the current WHO classification (11) (expert consensus; recommendation grade A). The more common subtypes are clear cell carcinoma (70%), types I and II papillary carcinoma (15%), and the chromophobe subtype (5%). Staging should be carried out according to the recommendations of the TNM classification (11, 12), which are due to be updated in December 2016 (recommendation grade A).

Until now, renal cell carcinoma has been graded according to the four-level Fuhrman classification. There is an expert consensus that, from 2016 onward, clear cell and papillary renal cell carcinomas should be graded according to the system of the World Health Organization–International Society of Urological Pathology (WHO–ISUP) (recommendation grade A). Chromophobe renal cell carcinomas, however, should not be graded (12) (recommendation grade A). Moreover, if the diagnosis is papillary renal cell carcinoma, it should be indicated whether the tumor is of type I or type II (12) (recommendation grade A).

Prognosis

Renal cell carcinoma accounts for 2.6% of all deaths from cancer in men, and 2.1% in women. The 5-year survival rate is high compared to that of other types of cancer, at 75% for men and 77% for women. The prognosis depends mainly on the stage of disease: for patients in stages I, II, III, and IV, respectively, the 5-year survival rate is 97%, 87%, 69%, and 14%.

Validated multifactorial prognostic models for patients with renal cell carcinoma are available for various time points along the course of disease and the course of treatment. These models predict outcomes more accurately than individual tumor features (13) (LoE 2 ++).

Multifactorial prognostic models may be useful for counseling patients with renal cell carcinoma (recommendation grade 0); the described and/or validated degree of accuracy of the model in question should always be borne in mind. There is insufficient evidence for the use of molecular markers for prognostication (e1) (expert consensus).

Biopsy

Until recently, tissue biopsy was held to be contraindicated for patients with suspected renal cell carcinoma without metastases, as there was thought to be a risk of tumor dissemination by the biopsy itself. This risk is now thought to be negligible, as no such cases have been described in the literature in the past 15 years. In any case, the current expert consensus maintains that renal masses of an uncertain nature should only be biopsied if the findings would affect the choice of treatment (e2) (recommendation grade B). Independently of this consideration, a biopsy should always be performed before an ablative treatment (e.g., cryoablation, radiofrequency ablation) (recommendation grade A).

There are two situations in which biopsy is necessary for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. If the histological diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma has not yet been confirmed or the histological subtype is not yet known, then either the primary tumor or a metastasis should be biopsied before systemic therapy is administered (recommendation grade A). A biopsy can also be performed before a planned cytoreductive nephrectomy (recommendation grade 0).

There is also an expert consensus that, regardless of the indication for the biopsy, it should be performed as a punched cylinder biopsy; at least two tissue samples should be taken under ultrasonographic or computed tomographyy (CT) guidance; and cystic lesions should not be biopsied (recommendation grade B).

Primary imaging evaluation

For the preoperative diagnostic evaluation of patients with primary renal cell carcinoma, computed tomography (CT) should be performed, according to uniform standards, for local staging and resection planning (LoE 1+, recommendation grade A). Native images should be obtained from the dome of the liver to the symphysis pubis, and intravascular contrast images should be obtained in the early arterial phase (kidneys to pelvic inlet) and the venous phase (dome of the liver to the symphysis pubis) (e3) (recommendation grade A).

Patients with suspected involvement of the renal veins or the inferior vena cava should undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which should also be performed according to uniform standards (e4) (LoE 1+, recommendation grade B). With regard to staging, there is an expert consensus that asymptomatic patients with malignant tumors greater than 3 cm in size should have a CT scan of the chest (recommendation grade B). If there is any clinical evidence of osseous metastases, a relevant imaging study should be performed (low-dose whole-body CT or MRI is better than skeletal scintigraphy for this purpose) (recommendation grade A). For patients with suspected brain metastases, a contrast-enhanced MRI scan of the head is the imaging study of choice.

The primary treatment of renal cell carcinoma without metastases

Locally confined renal cell carcinoma should be treated surgically with curative intent (recommendation grade A). Nephrectomy (total or partial) is the standard treatment. Studies have not revealed any difference between open and laparoscopic nephrectomy in terns of overall or tumor-specific survival. Adequate data are not yet available on survival times after retroperitoneoscopic and robot-assisted nephrectomy. With open nephrectomy, in comparison to laparoscopic nephrectomy, the intraoperative blood loss is twice as great, and the mean hospital stay twice as long.

Locally confined tumors in clinical stage T1 should be managed with kidney-preserving surgery (recommendation grade A); this is also desirable for locally confined tumors in clinical stage T2 (14) (LoE 3, recommendation grade B).

Open partial nephrectomy is the standard organ-preserving operation (15) (LoE 4). This can be done as a minimally invasive procedure if the surgeon has the requisite experience (recommendation grade 0). In any partial nephrectomy, the duration of ischemia should be kept as short as possible (16) (LoE 3, recommendation grade A).

If kidney-preserving surgery is not possible, nephrectomy should be performed as a minimally invasive procedure (14) (LoE 3, recommendation grade B).

In surgery for renal cell carcinoma, if the imaging studies and intraoperative findings do not suggest lymph-node involvement, then no systematic or extended lymphadenectomy should be performed (17) (LoE 1+, recommendation grade A).

For patients with enlarged lymph nodes, a lymphadenectomy can be performed for local staging and local tumor control (recommendation grade 0). Adrenalectomy should not be performed if the imaging studies and intraoperative findings do not suggest adrenal involvement (18) (LoE 3, recommendation grade A).

It is important to point out that there have only been a very small number of prospective, randomized trials on the surgical treatment (approach, extent, and technique of resection) of locally confined (T1–2N0M0) or locally advanced (T3–4N0M0 or T1–4N+M0) renal cell carcinoma.

Resection margins

When renal tumors are removed, an R0 resection should be performed (19) (LoE 3, recommendation grade A). The presence of R1 findings when the resection bed is grossly tumor-free has not been shown to have any significant effect on tumor-specific survival (19) (LoE 3). Patients with R1 findings are at increased risk of local recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] 11.5); note, however, that the data underlying this finding concerned a small group of patients (20) (LoE 3). If the definitive histopathological examination reveals R1 findings, then surveillance is indicated, rather than a second operation (21) (LoE 3, recommendation grade B). If the resection bed is grossly tumor-free, then there is no need for an intraoperative frozen section (LoE 3, recommendation grade 0).

Radiofrequency tumor ablation or cryoablation

Cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation can be offered to patients with small renal tumors who have high comorbidity and/or a limited life expectancy (<5 years) (22) (LoE 2). A percutaneous renal tumor biopsy should be performed before any ablative procedure (22) (LoE 3, recommendation grade A).

Surveillance

There are no objective criteria for the selection of suitable patients, nor is there any uniform definition of the terms “active surveillance” and “watchful waiting” in renal cell carcinoma. Patients with a small renal tumor (≤ 4 cm) who have high comorbidity and/or a limited life expectancy (<5 years) can be managed by tumor surveillance (23) (LoE 3, recommendation grade 0). A biopsy should be performed before the surveillance period (recommendation grade A).

A therapeutic procedure can be performed later, e.g., if the patient so desires (with curative intent, in this situation) or if the tumor grows larger (to prevent tumor-associated symptoms and/or complications). Prospective randomized trials of cryoablation or radiofrequency ablation are lacking, as are prospective randomized trials of the surveillance concept.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy plays no role in the treatment of locally confined or locally advanced renal cell carcinoma.

The follow-up of renal cell carcinoma without metastases

After primary tumor treatment, patients who have no metastases should undergo risk-adapted follow-up (recommendation grade A). The risk-group classification for follow-up is determined by the pT and pN categories, the tumor grade, the type of treatment (resection vs. ablative techniques), and the R status (expert consensus).

The risk-adapted follow-up of patients who have undergone local treatment for renal cell carcinoma without metastases should include history-taking and physical examination, laboratory tests, CT/MRI of the abdomen and pelvis, chest CT with bone windows, and ultrasonography (recommendation grade B). On the other hand, studies that are not indicated for the routine follow-up of asymptomatic patients include combined positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT), CT and MRI of the head, conventional chest x-rays, and bone scintigraphy (expert consensus). Depending on the risk classification (Table 1), different test modalities and intervals between tests are recommended (Table 2).

Table 1. Risk-group classification for follow-up after the local surgical treatment _of renal cell carcinoma.

| Risk group | Features |

|---|---|

| Low risk | pT1a/b cN0 cM0 G1–2 |

| Intermediate risk | pT1a/b. cN0. cM0. G3. pT2. c/pN0. cM0. G1–2 _ablative treatment or R1 status in an otherwise low-risk patient |

| High risk | pT2. c/pN0. cM0. G3. pT3–4 and/or pN+ |

Table 2. Recommended follow-up scheme for patients at risk of recurrence.

| Time point / diagnostic tests | 3 Months | 6 Mo. | 12 Mo. | 18 Mo. | 24 Mo. | 36 Mo. | 48 Mo. | 60 Mo. | 84 Mo. | 108 Mo. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients at low risk of recurrence | ||||||||||

| History & physical examination | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Laboratory tests | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Abdominal ultrasonography | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Chest CT | x | x | x | |||||||

| Abdominal CT | (x)* | x | x | |||||||

| Patients at moderate risk of recurrence | ||||||||||

| History & physical examination | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Laboratory tests | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Abdominal ultrasonography | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Chest CT | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Abdominal CT | (x)* | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Patients at high risk of recurrence | ||||||||||

| History & physical examination | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Laboratory tests | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Abdominal ultrasonography | x | (x)* | x | x | x | |||||

| Chest CT | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Abdominal CT | (x) | (x) | x | x | x | x | x | |||

*Patients who have undergone partial nephrectomy for the treatment of complex tumors are in a special situation: when there are extensive or centrally located resection defects in the kidney. recurrent tumor can often be hard to to distinguish from scarring. either by ultrasonography or by tomographic imaging (CT or MRI).For routine practice. it has been found useful to obtain a baseline CT or MRI scan 8–12 weeks after partial nephrectomy to serve as a basis for comparison with future scans. It is up to the surgeon to decide whether a baseline scan is indicated in the light of the operative findings. and. if so. to integrate this scan into the follow-up scheme. In the chart above. the baseline scan is designated by an x in parentheses.

Systemic treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma

The treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is palliative rather than curative. The immune drugs interferon and interleukin, used for this purpose until 2004, were associated with a median overall survival of 1 to 1.5 years (24) (LoE 1++).

The targeted drugs that first became available in 2005 have markedly prolonged survival times. Seven such drugs are available at present:

5 VEGF inhibitors (sunitinib, sorafenib, bevacizumab, axitinib, pazopanib)

2 mTOR inhibitors (temsirolimus and everolimus).

Table 3 lists the current uses of the individual drugs, subdivided according to the tumor risk profile and the line of treatment.

Table 3. The use of targeted drugs according to tumor risk profile and line of treatment.

| Line of treatment | Risk profile | Standard | Alternative |

| First-line | Low/moderate | Bevacizumab + IFN-alpha Pazopanib Sunitinib |

High-dose interleukin-2 |

| High | Temsirolimus | Pazopanib. sunitinib | |

| Line of treatment | Prior treatment with: | Standard | Alternative |

| Second-line | Cytokines | Axitinib | Pazopanib Sorafenib |

| VEGF failure | Everolimus | ||

| Sunitinib | Axitinib Everolimus |

||

| Temsirolimus | Axitinib Pazopanib Sorafenib Sunitinib |

IFN-alpha. interferon-alpha; VEGF. vascular endothelial growth factor

The risk profile for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, as defined by Motzer, takes the following elements into account (25) (LoE 1+):

Performance status

The interval from diagnosis to systemic treatment

Hemoglobin concentration

Calcium concentration

Lactate dehydrogenase concentration

Patients with a favorable risk profile (no risk factors) have a median overall survival time of 43.2 months; the corresponding figures for patients with intermediate (1-2 risk factors) and unfavorable risk profiles (3 or more risk factors) are 22.5 and 7.8 months, respectively. The results of the drug-approval trials are summarized in Table 4 (26– 32) (LoE 1+).

Sequential drug therapy has been found to yield further improvement (33) (LoE 1+). No benefit, however, has been found for combination therapies, although this is mainly because of their side effects. The most common side effects of targeted drugs for renal cell carcinoma are (28, 30, 32, 34) (LoE 1+):

Hand-foot syndrome

Arterial hypertension

Diarrhea

Fatigue.

Neo-adjuvant/adjuvant therapy

The available data on neo-adjuvant and adjuvant therapy do not support their use in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Neo-adjuvant therapy does not reduce the volume of the primary tumor or of a vena cava thrombus to any clinically relevant extent (e5, e6) (LoE 3). No adjuvant drug regimen has yet been found to be beneficial. It follows that adjuvant therapy with a targeted drug or drugs should only be performed in the setting of a clinical trial (LoE 4, recommendation grade A).

Resection and radiotherapy of metastases

It was already shown in two large-scale, prospective, randomized trials in the era of immune therapy (35) (LoE 1++), and it remains true in the current era of target-specific therapy, that patients with an ECOG performance status of 0–1 who have synchronous metastases at the time of diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma stand to benefit from resection of the primary tumor (36) (LoE 2-), (37) (LoE 3) (recommendation grade A). Clinical decision-making in this regard must, of course, take the individual patient’s extent of metastatic disease, comorbidities, and current disease manifestations into account (recommendation grade B).

The local treatment of metastases under certain conditions likewise plays a greater role in the management strategy for renal cell carcinoma than for other kinds of tumor. Solitary, metachronically arising metastases should be resected regardless of the organ system in which they are located, as long as an R0 resection seems possible (e7, e8) (LoE 3, recommendation grade B). The most extensive data in this regard concern metastases of renal cell carcinoma to the lungs (e9, e10) (LoE 3). This concept may also apply to multiple metastases arising metachronically in a single organ system (e8) (LoE 3, recommendation grade 0).

Radiotherapy is a further mode of local treatment (e11). Particularly when an R0 resection is not possible or surgery cannot be performed for other reasons, radiotherapy is a good alternative. The options include high-dose external radiotherapy, radiosurgery (i.e., single-session stereotactic irradiation), or stereotactic radiotherapy (i.e., multiple-session stereotactic irradiation). The latter two methods are mainly used to treat bone and brain metastases (e12) (LoE 3), (e13). Radiotherapy can be given palliatively to treat osseous metastases that are causing bone pain or a risk of fracture (e14) (LoE 2+), or for the local control of brain metastases (e15) (LoE 3).

New data and future prospects

The next few years will likely see the identification of new prognostic and predictive markers that may be helpful in clinical decision-making (treatment vs. no treatment; if treatment is to be given, then with what drug?), in the surveillance of treatment effects during the treatment phase, and in further follow-up.

New data have been published since the completion of the S3 guideline, particularly with regard to the systemic treatment of renal cell carcinoma. New data on the adjuvant therapy of renal cell carcinoma without metastases are worthy of mention here. An initial randomized trial had shown no benefit from adjuvant therapy with sunitinib or sorafenib compared to placebo (38). Two randomized phase III trials have now shown that nivolumab, when given as second-line therapy of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma, yields longer overall survival than everolimus, and that cabozantinib yields longer progression-free survival than everolimus (39, 40). These data imply new possibilities for sequential or combination therapy and will be taken into account in the formulation of an amendment to the guideline that is to be published in the fall of 2016.

Table 4. Efficacy data from the approval and update trials of the targeted drugs for renal cell carcinoma.

| Treatment / control | Prior treatment | Median PFS (months) | Median overall survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib Placebo |

none | 5.5 2.8 |

19.3 15.9 (p=0.02) |

| Sunitinib IFN-alpha |

none | 11 5 |

26.4 21.8 (p=0.051) |

| Pazopanib Placebo |

none or cytokines | 9.2 4.2 |

22.9 20.5 (p=0.224) |

| Pazopanib Sunitinib |

none | 8.4 9.5 |

28.4 29.3 (p=0.28) |

| Bevacizumab + IFN-alpha Placebo + IFN-alpha |

none | 10.2 5.4 |

23.3 21.3 (p=0.336) |

| Temsirolimus* Temsirolimus + IFN-alpha IFN-alpha |

none | 5.5 4.7 3.1 |

10.9 8.4 7.3 (p=0.008 for temsirolimus vs. IFN-alpha) |

| Axitinib Sorafenib |

VEGF inhibitor or cytokines | 6.7 4.7 |

20.1 19.2 (p=0.374) |

| Everolimus Placebo |

VEGF inhibitor | 4.9 1.9 |

14.8 14.4 (p=0.162) |

*in patients with an unfavorable risk profile IFN-alpha. interferon-alpha; p. singifiance value; PFS. progression-free survival; VEGF. vascular endothelial growth factor; vs.. versus

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Doehn owns stock in Bayer Healthcare, AstraZeneca, and BMS. He has served as a paid consultant for Bayer Healthcare, BMS, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. He has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees from BMS, GSK, Novartis, and Pfizer, and reimbursement of travel and accommodation expenses from BMS, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. He has received payment for preparing scientific meetings from Bayer Healthcare, BMS, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

Prof. Grünwald has served as a paid consultant for BMS, Pfizer, Novartis, and Bayer. He has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and travel and accommodation expenses, as well as payment for preparing scientific meetings, from BMS, Novartis, and Pfizer.

Prof. Steiner, Prof. Krege, Dr. Follmann, and H. Rexer state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Robert Koch-Institut. Krebs in Deutschland 2009/10. www.rki.de/Krebs/DE/Content/Publikationen/Krebs_in_Deutschland/kid_2013/krebs_in_deutschland_2013.pdf; jsessio nid=0BE7FFCB4020E20CEE977217CD5A350B.2_cid298?__blob=publicationFile. (last accessed on 12 July 2015)

- 2.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie. S3 Leitlinie Nierenzellkarzinom. (last accessed on 7 January 2016)

- 3.Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin. Leitlinien-Methodik. (last accessed on 7 January 2016)

- 4.AWMF. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie. S3 leitlinie Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Nierenzellkarzinoms. (last accessed on 7 January 2016)

- 5.Healthcare Improvement Scotland. SIGn A guideline developer’s handbook. (last accessed on 7 January 2016)

- 6.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie. Entwicklung von Leitlinien basierten Qualitätsindikatoren. (last accessed on 7 January 2016)

- 7.Hunt JD, van der Hel OL, McMillan GP, Boffetta P, Brennan P. Renal cell carcinoma in relation to cigarette smoking: meta-analysis of 24 studies. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:10–18. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow WH, Gridley G, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Järvholm B. Obesity, hypertension, and the risk of kidney cancer in men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1305–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Port FK, Ragheb NE, Schwartz AG, Hawthorne VM. Neoplasms in dialysis patients: a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;14:119–123. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(89)80187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clague J, Lin J, Cassidy A, et al. Family history and risk of renal cell carcinoma: results from a case-control study and systematic meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:801–807. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of renal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1469–1489. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delahunt B, Cheville JC, Martignoni G, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading system for renal cell carcinoma and other prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1490–1504. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f0fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan MH, Li H, Choong CV, et al. The Karakiewicz nomogram is the most useful clinical predictor for survival outcomes in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2011;117:5314–5324. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacLennan S, Imamura M, Lapitan MC, et al. Systematic review of oncological outcomes following surgical management of localised renal cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;61:972–993. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Poppel H, Becker F, Cadeddu JA, et al. Treatment of localised renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopp RP, Mehrazin R, Palazzi K, Bazzi WM, Patterson AL, Derweesh IH. Factors affecting renal function after open partial nephrectomy—a comparison of clampless and clamped warm ischemic technique. Urology. 2012;80:865–870. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blom JH, van Poppel H, Marechal JM, et al. Radical nephrectomy with and without lymph-node dissection: final results of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomized phase 3 trial 30881. Eur Urol. 2009;55:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekema HJ, MacLennan S, Imamura M, et al. Systematic review of adrenalectomy and lymph node dissection in locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013;64:799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marszalek M, Meixl H, Polajnar M, Rauchenwald M, Jeschke K, Madersbacher S. Laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomy: a matched- pair comparison of 200 patients. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernhard JC, Pantuck AJ, Wallerand H, et al. Predictive factors for ipsilateral recurrence after nephron-sparing surgery in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2010;57:1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bensalah K, Pantuck AJ, Rioux-Leclercq N, et al. Positive surgical margin appears to have negligible impact on survival of renal cell carcinomas treated by nephron-sparing surgery. Eur Urol. 2010;57:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Dib R, Touma NJ, Kapoor A. Cryoablation vs radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of case series studies. BJU Int. 2012;110:510–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smaldone MC, Kutikov A, Egleston BL, et al. Small renal masses progressing to metastases under active surveillance: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Cancer. 2012;118:997–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gore ME, Griffin CL, Hancock B, et al. Interferon alpha-2a versus combination therapy with interferon alpha-2a, interleukin-2, and fluorouracil in patients with untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (MRC RE04/ EORTC GU 30012): an open-label randomized trial. Lancet. 2010;375:641–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61921-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. TARGET Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1061–1018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alpha, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alpha-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2103–2111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rini BE, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1931–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motzer R, Barrios CH, Kim TM, et al. Record-3: Phase II randomized trial comparing sequential first-line Everolimus (EVE) and second-line sunitinib (SUN) versus first-line SUN and second-line EVE in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2765–2772. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhojani N, Jeldres C, Patard JJ, et al. Toxicities associated with the administration of sorafenib, sunitinib, and temsirolimus and their management in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2008;53:917–930. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, Tangen C, Van Poppel H, Crawford ED. Cytoreductive therapy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol. 2004;171:1071–1076. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110610.61545.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiess PE, Fishman MN. Cytoreductive nephrectomy vs medical therapy as initial treatment: a rational approach to the sequence question in metastatic renal cell cancer. Cancer Control. 2010;17:269–278. doi: 10.1177/107327481001700407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gore ME, Szczylik C, Porta C, et al. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: an expanded access trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:757–763. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haas NB, Manola J, Uzzo RG, et al. Adjuvant sunitinib or sorafenib for high-risk, non-metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (ECOG-ACRIN E2805): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:2008–2016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00559-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1814–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Tan PH, Cheng L, Rioux-Leclercq N, et al. Renal tumors: diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1518–1531. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f12e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Volpe A, Finelli A, Gill IS, et al. Rationale for percutaneous biopsy and histologic characterisation of renal tumours. Eur Urol. 2012;62:491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Hallscheidt PJ, Bock M, Riedasch G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of staging renal cell carcinomas using multidetector-row computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging: a prospective study with histopathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:333–339. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Guzzo TJ, Pierorazio PM, Schaeffer EM, Fishman EK, Allaf ME. The accuracy of multidetector computerized tomography for evaluating tumor thrombus in patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2009;181:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Bex A, Powles T, Karam JA. Role of targeted therapy in combination with surgery in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol. 2016;23:5–12. doi: 10.1111/iju.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Thillai K, Allan S, Powles T, Rudman S, Chowdhury S. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:765–776. doi: 10.1586/era.12.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Kavolius JP, Mastorakos DP, Pavlovich C, Russo P, Burt ME, Brady MS. Resection of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2261–2266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.van der Poel HG, Roukema JA, Horenblas S, van Geel AN, Debruyne FM. Metastasectomy in renal cell carcinoma: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Eur Urol. 1999;35:197–203. doi: 10.1159/000019849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Meimarakis G, Angele M, Staehler M, et al. Evaluation of a new prognostic score (Munich score) to predict long-term survival after resection of pulmonary renal cell carcinoma metastases. Am J Surg. 2011;202:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Kudelin N, Bölükbas S, Eberlein M, Schirren J. Metastasectomy with standardized lymph node dissection for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an 11-year single-center experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.De Meerleer G, Khoo V, Escudier B, et al. Radiotherapy for renal-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:70–77. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70569-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Thibault I, Al-Omair A, Masucci GL, et al. Spine stereotactic body radiotherapy for renal cell cancer spinal metastases: analysis of outcomes and risk of vertebral compression fracture. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;21:711–718. doi: 10.3171/2014.7.SPINE13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Blanco AI, Teh BS, Amato RJ. Role of radiation therapy in the management of renal cell cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:4010–4023. doi: 10.3390/cancers3044010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Chow E, Zeng L, Salvo N, Dennis K, Tsao M, Lutz S. Update on the systematic review of palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Bennani O, Derrey S, Langlois O, et al. Brain metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. Neurochirurgie. 2014;60:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]