Abstract

Objective

We conducted a pragmatic randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of an asthma question prompt list with video intervention to increase youth question-asking and provider education during visits.

Methods

English or Spanish-speaking youth ages 11–17 with persistent asthma and their parents were enrolled from four rural and suburban pediatric clinics. Youth were randomized to the intervention or usual care groups. Intervention group adolescents watched the video on an iPad and then completed an asthma question prompt list before their visits. Generalized estimating equations were used to analyze the data.

Results

Forty providers and 359 patients participated. Intervention group youth were significantly more likely to ask one or more questions about medications, triggers, and environmental control than usual care youth. Providers were significantly more likely to educate intervention group youth about rescue medications, triggers, and environmental control. Intervention group caregivers were not significantly more likely to ask questions.

Conclusion

The intervention increased youth question-asking and provider education about medications, triggers, and environmental control. The intervention did not impact caregiver question-asking.

Practice Implications

Providers/practices should consider having youth complete question prompt lists and watch the video with their parents before visits to increase youth question-asking during visits.

Keywords: question-asking, youth, provider education, educational video intervention, question prompt list, asthma

1. Introduction

Research has shown that children and adolescents are not actively involved during their medical visits[1, 2]. Traditionally, the adolescent’s contribution during medical visits has been limited to approximately 10% of the visit and the communication is dominated by the physician and parent [1, 2]. Parents often restrict the adolescent’s participation and want to dominate the medical visit [1]. However, actively involving youth during visits could improve their medication knowledge and their overall physical functioning [3, 4]. Street and colleagues [5, 6] posit that patient-provider communication can improve a clinical outcome directly as well as indirectly via increased patient engagement in self-care skills.

In our prior work that examined provider-patient communication during pediatric asthma visits, we found that only 13% of adolescents asked questions about asthma management and that the majority of questions that adolescents asked were about asthma medications [7]. We also found that 78% of adolescents expressed one or more asthma medication problems yet only 11% asked a question about their medications during their medical visits [8–12]. One potential way to improve youth involvement during visits is through the use of “question prompt lists”. Cancer researchers have found that giving cancer patients “question prompt lists” before their visits increased the number of questions that patients asked their doctors, improved patient recall of information, and prompted doctors to give patients more information [13–16]. A “question prompt list” is a list of common questions a patient might want to ask their doctor about their condition and its treatment. This paper reports on the initial results of a pragmatic randomized, controlled trial (RCT) testing the effectiveness of an asthma question prompt list with short video intervention compared to usual care. We examine whether youth in the intervention group were more likely to ask one or more questions about medications, triggers, and environmental control than youth in the usual care group. We also investigate whether providers were more likely to educate youth in the intervention group about control medications, rescue medications, triggers, and environmental control than youth in the usual care group.

2. Methods

2.1 Description of Intervention

The question prompt list and video intervention seeks to motivate adolescents to ask questions they have about asthma management so that they can better understand how to manage their asthma after leaving the doctor’s office. The intervention is based on Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)[17–19]. Self-confidence or self-efficacy is a central component of SCT. Application of SCT in pediatric asthma populations has shown that technical advice from providers is one external factor that can improve adolescents’ self-management self-efficacy [20, 21]. Prior work has found that adolescent self-efficacy in asthma management correlates strongly with health status, adherence, asthma medication device technique, asthma symptoms, and impact of illness on the family [22–24].

The question prompt list with video intervention uses pre-visit wait time to encourage youth to be more actively involved during asthma visits. The video was eleven minutes in length and had six themes (asthma triggers, staying active with asthma, how to get mom off your back, tracking asthma symptoms, how to talk to your doctor, and having confidence with asthma) which is discussed in detail elsewhere self-efficacy [18]. Each theme had its own video that ranged in length from one to two minutes. The final one-page asthma question prompt list had 14 questions about asthma medications, eight questions about triggers and asthma in general, and an area where adolescents could write in questions. The question prompt list took adolescents in the intervention group less than four minutes to complete.

2.2 Procedure

Forty-six providers from four pediatric practices (one academic and three private) in North Carolina agreed to participate in the study. Two clinics were in rural areas and two were in suburban areas of North Carolina. Clinic staff referred potentially eligible patients who were interested in learning more about the study to a research assistant. During pre-visit wait time, the research assistant explained the study, obtained written parent consent and adolescent assent, and administered an eligibility screener [25, 26]. Children were eligible if they were: ages 11 to 17 years; spoke and read English or Spanish; had persistent asthma; were present for an acute or follow-up asthma visit or a well-child visit; and had previously visited the clinic at least once for asthma. Using information from the eligibility screener that parents completed with the research assistant, persistent asthma was defined as experiencing asthma-related daytime symptoms more than twice a week, asthma-related nighttime symptoms more than twice a month, or receiving one or more long-term controller therapies for asthma [11, 22].

The study statistician prepared the randomization envelopes for the research assistants to use. Adolescents were randomized within providers and opaque envelopes were prepared for the research assistants at each site. A group of envelopes was prepared for each enrolled provider. Eligible adolescents of participating providers were then randomized to the intervention or usual care group. Adolescents in the intervention group watched the video with their parents on an iPad. Depending on the clinic, they either watched it in a private area before the visit or they watched it with earphones in the waiting area. The adolescents then received the one-page asthma question prompt list to complete before their visits. Providers were blinded to the adolescent’s group assignment. All adolescents’ visits were audio-tape recorded. All adolescents were interviewed after their medical visits by a research assistant while their parents completed questionnaires. Adolescents and parents each received $25 for their time.

2.3 Measurement

Adolescent age, years the adolescent has been living with asthma, parent years of education, and provider age were measured as continuous variables. Adolescent and provider sex were measured as dichotomous variables. Adolescent and provider race/ethnicity were coded into five categories: Non-Hispanic White, African American, Native American/American Indian, Hispanic, or Other. Parent report of language spoken at home with their child was measured as English or Spanish. Asthma severity was classified as mild persistent versus moderate/severe persistent according to the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute’s guidelines [25, 26]. We also created variables on whether the adolescent and provider were sex concordant and whether they were racially/ethnically concordant.

2.4 Communication during Visit

All of the medical visit audio-tapes were transcribed verbatim. Three research assistants were trained to code the transcripts using a detailed tool developed and used in prior asthma communication work [8, 10, 22]. The transcriptionists and coders were blinded as to whether patients were in the intervention or usual care groups. The research assistants coded the following: (a) whether the youth asked one or more questions about asthma medications, asthma triggers, and environmental control during the visit and (b) how many questions they asked in each area. They also coded whether the provider educated youth during visits about the following areas: control medications, rescue medications, asthma triggers, and environmental control. Three coders coded thirty-four of the same transcripts throughout the study period to assess inter-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability ranged from 0.77 to 0.98 for the following communication variables: (a) whether the youth asked one or more questions about asthma medications was 0.98, (b) whether the youth asked one or more questions about asthma triggers was 0.92, (c) whether the provider educated about control medications was 0.80, (d) whether the provider educated about rescue medications was 0.86, (e) whether the provider educated about asthma triggers was 0.77, and (f) whether the provider educated about environmental control was 0.86. The inter-coder reliability could not be calculated for whether the youth asked one or more questions about environmental control since it never occurred in the reliability transcripts, but the coders agreed 100% of the time that it did not occur.

2.5 Analysis

Before beginning enrollment into the study, we conducted an a priori power analysis. A sample of 359 adolescents provided 80% power to detect between-group differences of 22% or more in whether youth ask one or more questions about asthma during their medical visits with a type I error rate of 5%. Based on our prior work, we expected about 12% of the children in the control group to ask one or more questions about asthma management and we expected an increase to 34% or higher in the experimental group[7].

All analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York). Youth and provider race/ethnicity were recoded into dichotomous variables (White, non-White). First, we computed descriptive statistics for all variables. Second, we examine bivariate relationships between the variables using Pearson chi-square statistics or independent t-tests. Language spoken at home was not significantly associated with any of the youth question-asking or provider education variables, so it was not included in the generalized estimating equations (GEE). Next, we used GEE to examine how: (a) study group (intervention, usual care), (b) youth sex, age, race/ethnicity, years living with asthma, asthma severity, (c) years of parent education, and (d) provider age, sex, and race/ethnicity were associated with whether the child asked one or more questions about asthma medications, environmental control, and triggers. Sex concordance of the adolescent and provider was significantly associated with whether the adolescent asked one or more questions about environmental control in the bivariate analysis, so it was included in the GEE predicting whether youth asked one or more questions about environmental control.

Finally, we used GEE to examine how (a) study group (intervention, usual care), (b) youth sex, age, race/ethnicity, years living with asthma, asthma severity, (c) years of parent education, and (d) provider age, sex, and race/ethnicity were associated with provider education about control medications, rescue medications, environmental control, and triggers. We also included whether the child asked one or more questions about asthma medications in the GEE models predicting provider education about control medications and provider education about rescue medications. We included whether the child asked a question about triggers in the GEE model predicting provider education about triggers. We included whether the child asked a question about environmental control in the GEE model predicting provider education about environmental control.

3. Results

Forty-six providers agreed to participate in the study and 40 of these providers enrolled patients. Providers ranged in age from 28 to 62 (mean age=41.2, standard deviation=11.2). Twenty-seven of the 40 providers who had patients enrolled into the study were female. Four providers were Native American, three were African American, three were Asian American, 29 were White, and one was Hispanic. Forty percent of the youth saw providers who were the same race or ethnicity as themselves. Sixty-one percent of the adolescents saw providers who were the same sex as themselves.

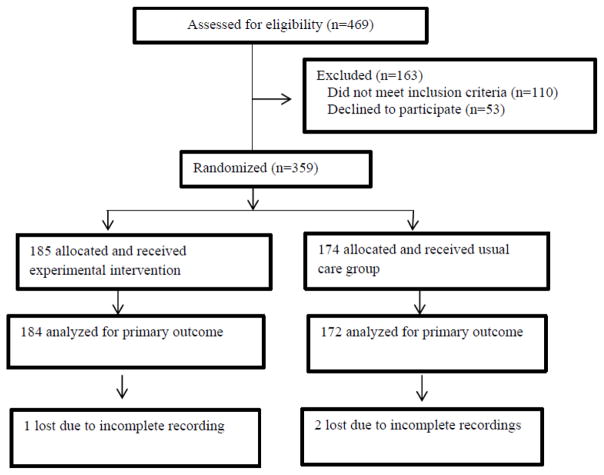

The participation of the patients in the trial is shown in the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram (Figure 1). Participants were enrolled from June 2015 to November 2016. One hundred and ten participants did not meet inclusion criteria. Of the 412 eligible patients, 359 agreed to participate and 53 refused (87% participation rate). Two hundred and nineteen patients were enrolled at clinics in rural areas and 140 were enrolled at clinics in suburban areas. There was an average of nine participants enrolled for each provider.

Figure 1.

Patient participation in the trial baseline visits.

Of the 359 enrolled families, 185 were randomly allocated to the experimental intervention group and 174 were allocated to the control group or usual care. Of 359 families recruited, we have conducted analysis of our primary outcome for 356 youth because three of the visits were not properly audio-tape recorded. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics by whether adolescents were randomized to the intervention or usual care. The groups were balanced on all adolescent and provider demographic characteristics. Nine percent of parents reported that they spoke Spanish at home and 91% spoke English at home.

Table 1.

Youth and provider characteristics

| Characteristics | Intervention Group (N=185) | Usual Care Group (N=174) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (N) | Percent (N) | P Value | |

| Youth Sex | |||

| Male | 58.9 (109) | 55.2 (96) | 0.522 |

| Female | 41.1 (76) | 44.8 (78) | |

| Youth Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 32.4 (60) | 40.2 (70) | 0.508 |

| African American | 38.4 (71) | 36.2 (63) | |

| Hispanic | 14.1 (26) | 10.9 (19) | |

| Native American | 13.0 (24) | 9.8 (17) | |

| Other | 2.2 (4) | 2.9 (5) | |

| Language spoken at home | |||

| English | 93.1 (162) | 89.7 (166) | 0.26 |

| Spanish | 6.9 (12) | 10.3 (19) | |

| Asthma Severity | |||

| Mild | 49.2 (91) | 44.3 (77) | 0.397 |

| Moderate/Severe | 50.8 (94) | 55.7 (97) | |

| Provider Sex | |||

| Male | 33.5 (62) | 32.2 (56) | 0.823 |

| Female | 66.5 (123) | 67.8 (118) | |

| Provider Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 73.0 (135) | 73.0 (127) | 0.970 |

| African American | 11.4 (21) | 10.9 (19) | |

| Asian American | 4.9 (9) | 6.3 (11) | |

| Hispanic | 1.6 (3) | 1.1 (2) | |

| Native American | 9.2 (17) | 8.6 (15) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Provider Type | |||

| Physician | 62.2 (115) | 62.6 (109) | 0.960 |

| Physician Assistant | 18.9 (35) | 17.8 (31) | |

| Nurse Practitioner | 18.9 (35) | 19.5 (34) | |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | P Value | |

| Youth Age | 13.2 (1.9) | 13.2 (1.9) | 0.655 |

| Years Living with Asthma | 5.1 (2.8) | 5.5 (2.9) | 0.196 |

| Parent Educational Level-years | 13.5 (3.1) | 13.8 (3.5) | 0.389 |

| Provider Age | 44.2 (11.5) | 44.0 (11.4) | 0.912 |

Table 2 presents the extent to which youth asked one or more questions about asthma medications, triggers, and environmental control. Youth in the intervention group were significantly more likely to ask one or more questions about asthma medications, triggers, and environmental control than youth in the usual care group. Forty percent of youth in the intervention group compared to 20% of youth in the usual care group asked one or more questions about medications. Sixteen percent of youth in the intervention group asked questions about triggers compared to 2% in the usual care group. Among youth who asked one or more questions, youth in the intervention group asked an average of 2.5 questions compared to youth in usual care asking 1.7 questions.

Table 2.

Youth question-asking and provider education about asthma medications, triggers, and environmental control

| Communication Variable | Intervention N=185 | Usual Care N=174 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (N) | Percent (N) | P value | |

| Youth Who Asked One or More Questions (N=359) | |||

| Asthma Medications | 40.2 (74) | 20.9 (36) | 0.0001 |

| Asthma Triggers | 16.3 (30) | 2.3 (4) | 0.0001 |

| Environmental Control | 5.4 (10) | 1.2 (2) | 0.037 |

| Number of Questions Youth Asked If They Asked One or More Questions (N=156) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | P value |

| Asthma Medications (N=110) | 2.51 (1.79) | 1.69 (1.43) | 0.018 |

| Asthma Triggers (N=34) | 1.67 (1.24) | 1.75 (0.96) | NA |

| Environmental Control (N=12) | 1.10 (0.32) | 1.00 (0.0) | NAa |

| Youth Whose Provider Educated Them During Visits (N=359) | Percent (N) | Percent (N) | P value |

| Control Medications | 77.2 (142) | 69.8 (120) | 0.113 |

| Rescue Medications | 78.3 (144) | 60.5 (104) | 0.0003 |

| Asthma Triggers | 59.2 (109) | 45.9 (79) | 0.012 |

| Environmental Control | 22.3 (41) | 12.8 (22) | 0.019 |

NOTE: t-tests, Chi square, and Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate for cell counts less than 5.

NA=not applicable which indicates too few subjects for valid testing.

When providers saw youth in the intervention group, they were significantly more likely to provide education about rescue medications, asthma triggers, and environmental control than when they saw youth in the usual care group. Providers educated 78% of youth in the intervention group about rescue medications compared to 60% of youth in usual care. Providers educated 59% of youth about asthma triggers in the intervention group compared to 46% in usual care. Providers were equally likely to educate youth in the intervention and usual care groups about asthma control medications.

Table 3 presents the GEE results predicting whether youth asked one or more questions about medications, asthma triggers, and environmental control. Youth in the intervention group were three times more likely to ask one or more questions about asthma medications than youth in the usual care group (odds ratio=3.08, 95% confidence interval (CI)=2.1, 4.5). Youth in the intervention group were over eight times more likely to ask one or more questions about triggers than youth in the usual care group (odds ratio=8.85, 95% CI=3.04, 25.75). Youth in the intervention group were six times more likely to ask a question about environmental control than youth in the usual care group (odds ratio=6.05, 95% CI=1.51, 24.1). Years of living with asthma was the only variable we controlled for that was significant in any model. The longer a youth had asthma, the less likely they were to ask a question about environmental control (odds ratio=0.84, 95% CI=0.73, 0.96). Adolescents who saw providers who were the same sex as themselves were significantly less likely to ask one or more questions about environmental control (odds ratio=0.22, 95% confidence interval=0.05, 0.94). Adolescents were significantly less likely to ask female providers about environmental control (odds ratio=0.20, 95% CI=0.05, 0.86). Caregivers of youth in the intervention group were not significantly more likely to ask questions about asthma medications, triggers, or environmental control than caregivers of youth in the usual care group (results not shown).

Table 3.

GEE predicting whether youth ask one or more questions about asthma medications, triggers, and environmental control during pediatric asthma visits (N=356)

| Independent Variables | Medications | Environmental Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Youth received intervention | 3.08 (2.1, 4.5)*** | 8.85 (3.04, 1.86)*** | 6.05 (1.51, 24.1)* |

| Youth sex-male | 0.65 (0.38, 1.1) | 0.84 (0.38, 1.86) | 0.80 (0.17, 3.7) |

| Youth race/ethnicity-White | 1.06 (0.62, 1.81) | 1.11 (0.57, 2.16) | 1.57 (0.38, 6.55) |

| Youth age | 1.04 (0.92, 1.16) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.37) | 1.03 (0.74, 1.43) |

| Years living with asthma | 1.04 (0.98, 1.11) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.02) | 0.84 (0.73, 0.96)* |

| Asthma severity-moderate/severe | 1.34 (0.84, 2.16) | 1.1 (0.39, 3.1) | 1.93 (0.56, 6.68) |

| Parent education (in years) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.11) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.02) | 0.87 (0.71, 1.05) |

| Provider age | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.05 (0.98, 1.1) |

| Provider sex-female | 0.65 (0.29, 1.46) | 0.45 (0.18, 1.15) | 0.2 (0.05, 0.86)* |

| Provider race/ethnicity-White | 0.94 (0.39, 2.3) | 2.16(0.74, 6.31) | 1.01 (0.35, 2.89) |

| Sex concordance between youth and provider | ------ | ------ | 0.22 (0.05, 0.94)* |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.001

CI=confidence interval

Table 4 presents the GEE results predicting whether providers educated youth about control medications, rescue medications, asthma triggers, and environmental control. Providers were significantly more likely to educate youth in the intervention group about rescue medications (odds ratio=1.92, 95% CI=1.12, 3.29), asthma triggers (odds ratio=1.7, 95% CI=1.2, 2.63), and environmental control (odds ratio=2.64, 95% CI=1.41, 4.95) than youth in the usual care group. Providers were significantly more likely to educate youth about control medications if the child had moderate/severe asthma (odds ratio=1.61, 95% CI=1.12, 2.31). Providers were significantly more likely to educate youth about control medications (odds ratio=2.21, 95% CI=1.16, 4.23), rescue medications (odds ratio=4.29, 95% CI=1.94, 9.92), asthma triggers (odds ratio=6.57, 95% CI=2.38, 18.12), and environmental control (odds ratio=15.71, 95% CI=3.99, 61.87) if youth asked one or more questions about medications, asthma triggers, and environmental control respectively.

Table 4.

GEE predicting whether provider educates about control medications, rescue medications, asthma triggers, and environmental control during pediatric asthma visits (N=356)

| Independent Variables | Control Medications | Rescue Medications | Asthma Triggers | Environmental Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Youth received intervention | 1.27 (0.83, 1.93) | 1.92 (1.12, 3.29)* | 1.7 (1.1, 2.63)* | 2.64 (1.41, 4.95)** |

| Youth asked one or more questions about medications | 2.21 (1.16, 4.23)* | 4.39 (1.94, 9.92)*** | ------- | ------- |

| Youth asked one or more questions about triggers | ------- | ------- | 6.57 (2.38, 18.12)*** | ------- |

| Youth asked one or more questions about environmental control | ------- | ------- | ------- | 15.71 (3.99, 61.87)*** |

| Youth sex-male | 0.93 (0.62, 1.37) | 1.08 (0.67, 1.73) | 1.15 (0.65, 2.04) | 1.0 (0.45, 2.26) |

| Youth race/ethnicity- White | 0.71 (0.48, 1.06) | 0. 79 (0.44, 1.41) | 1.27 (0.76, 2.11) | 1.0 (0.53, 1.95) |

| Youth age | 0.95 (0.82, 1.09) | 1.0 (0.88, 1.14) | 0.94 (0.82, 1.1) | 0.95 (0.77, 1.17) |

| Years living with asthma | 1.08 (0.96, 1.21) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) |

| Asthma severity- moderate/severe | 1.61 (1.12, 2.31)* | 1.07 (0.70, 1.64) | 1.29 (0.82, 2.01) | 1.51 (0.76, 2.98) |

| Parent education (in years) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) |

| Provider age | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) |

| Provider sex- female | 0.60 (0.33, 1.12) | 1.71 (0.80, 3.65) | 0.94 (0.59, 1.49) | 0.55 (0.19, 1.57) |

| Provider race/ethnicity- White | 1.22 (0.67, 2.24) | 0.98 (0.41, 2.27) | 1.78 (1.0, 3.16) | 2.00 (0.63, 6.42) |

p < 0.05,

< 0.01,

p < 0.001

CI=confidence interval

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

The asthma question prompt list with video intervention resulted in children being more likely to ask one or more questions about medications, triggers, and environmental control during their visits. This is similar to prior research in the cancer area which found that when adult patients used question prompt lists they asked more questions during visits[13–16]. In our prior work we found that only 13% of adolescents asked questions about asthma management and that the majority of questions that adolescents asked were about asthma medications[7]. In the current study, 40% of the youth in our intervention group asked one or more questions about asthma medications, 16% asked about triggers, and 5% asked about environmental control.

Our intervention helped empower adolescents to be more involved during visits. Prior work has found that parents can often restrict the adolescent’s participation during pediatric visits and providers often limit interactions with adolescents to “social talk”[1]. Butz et al.[27] suggested that a visual aid can be an effective communication tool for use with children/adolescents. They suggested using comic books[27] as visual aids, but we found that youth reported the asthma question prompt list and video useful[17]. Adolescent involvement during visits can improve satisfaction, adherence to recommendations, and patient health outcomes[7, 22, 26, 28–32]. Our cohort of enrolled adolescents is being followed for one year so that their clinical outcomes can be investigated in the future.

Another important finding from our study is that providers were significantly more likely to educate youth in the intervention group about rescue medications, triggers, and environmental control than youth in the usual care group. Prior research in the cancer area found that when patients used question prompt lists, providers were more likely to give patients more information[13–16]. Providers were not significantly more likely to educate youth in the intervention group about control medications. However, providers were significantly more likely to educate youth with moderate/severe persistent asthma about control medications than youth with mild persistent asthma. Importantly, providers were significantly more likely to educate youth about control medications if the youth asked one or more questions about medications.

In addition, if youth asked one or more questions about medications they were significantly more likely to be educated about rescue medications. If they asked one or more questions about triggers, they were significantly more likely to be educated about triggers by providers. If they asked one or more questions about environmental control, they were significantly more likely to be educated about environmental control.

4.1.2 Study Limitations

The study is limited in generalizability in that it was conducted in four pediatric clinics in North Carolina. Another limitation is that we do not know how many patients who the clinic staff referred chose not to talk to the research assistant. However, we could not ask the clinic staff to track these numbers because of the busyness of the clinics and our promise not to interrupt flow. Another limitation is that we did not code from the transcripts whether providers educated youth before or after the adolescent asked one or more questions which precluded us from knowing if there was a bidirectional relationship between the two. Even though youth were randomized within providers, there was no evidence of contamination since the intervention was successful at increasing youth question-asking in the intervention group but not the usual care group. The youth were enrolled over a fifteen-month period so each clinic enrolled approximately five to eight patients a month, so each provider might have only enrolled one to two patients a month and some of those enrolled patients would have been in the usual care group, which further limits the likelihood of contamination. Despite the study limitations, the study demonstrated that an asthma question prompt list with video intervention improved youth question-asking during pediatric asthma visits and increased the extent to which providers educated youth about rescue medications, triggers, and environmental control. Another limitation is that the providers might have been unblinded if the provider noticed the youth using the one-page question prompt list during the visit.

4.2 Conclusion

The asthma question prompt list with video intervention significantly increased youth question-asking and provider education about medications, triggers, and environmental control.

4.3 Practice Implications

The question prompt list and video intervention is brief, easy to implement, and inexpensive. The English and Spanish videos are on a YouTube channel (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCSbQklyoYDLuwa-x-KeGIiQ). The intervention was successful at increasing youth question-asking about asthma medications, triggers, and environmental control. Providers who wish to increase youth involvement during asthma visits may want to consider implementing this brief intervention during pre-visit wait time.

Highlights.

Youth in question prompt list with video intervention more likely to ask questions

Providers more likely to educate youth who watched video and used prompt list

Providers were more likely to educate youth who asked one or more questions

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program Award (1402-09777). The project is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT02498834, protocol ID 14-2628). Drs. Sleath and Reuland are also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number 1UL1TR001111.

Footnotes

Contributors' Statement: Drs. Sleath and Tudor contributed to conceptualization and the design of the study, data analysis and interpretation of data, and they drafted the initial manuscript. Scott Davis and Dr. Claire Hayes Watson contributed to data analysis and interpretation of data and they reviewed and revised the manuscript. Nacire Garcia and Drs. Lee, Carpenter, Reuland, and Loughlin contributed to the conception and design of study, acquisition of data, and they reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Conflict of Interest: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tates K, Meeuwesen L. Doctor-parent-child communication. A (re)view of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:839–851. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wissow LS, Roter D, Bauman LJ, Crain E, Kercsmar C, Weiss K, Mitchell H, Mohr B. Med Care. Vol. 36. The National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH; Bethesda, MD: 1998. Patient-provider communication during the emergency department care of children with asthma; pp. 1439–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinson W. Doctor-patient communication and medical malpractice: implications for pediatricians. Pediatr Ann. 1997;26:186–193. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19970301-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Neill KA. Kids speak: effective communication with the school-aged/adolescent patient. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:137–140. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200204000-00018. None. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Street RL, Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Street RL., Jr How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sleath BL, Carpenter DM, Sayner R, Ayala GX, Williams D, Davis S, Tudor G, Yeatts K. Child and caregiver involvement and shared decision-making during asthma pediatric visits. J Asthma. 2011;48:1022–1031. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.626482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Beard A, Gillette C, Williams D, Tudor G, Ayala GX. Child and caregiver reported problems in using asthma medications and question-asking during paediatric asthma visits. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22:69–75. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Ayala GX, Williams D, Davis S, Tudor G, Yeatts K, Gillette C. Communication during pediatric asthma visits and child asthma medication device technique 1 month later. J Asthma. 2012;49:918–925. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.719250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Ayala GX, Williams D, Davis S, Tudor G, Yeatts K, Gillette C. Provider discussion, education, and question-asking about control medications during pediatric asthma visits. Int J Pediatr. 2011;2011:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2011/212160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sleath B, Ayala GX, Gillette C, Williams D, Davis S, Tudor G, Yeatts K, Washington D. Provider demonstration and assessment of child device technique during pediatric asthma visits. Pediatrics. 2011;127:642–648. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleath B, Ayala GX, Davis S, Williams D, Tudor G, Yeatts K, Washington D, Gillette C. Child- and caregiver-reported problems and concerns in using asthma medications. J Asthma. 2010;47:633–638. doi: 10.3109/02770901003692785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimoska A, Tattersall MH, Butow PN, Shepherd H, Kinnersley P. Can a "prompt list" empower cancer patients to ask relevant questions? Cancer. 2008;113:225–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smets EM, van Heijl M, van Wijngaarden AK, Henselmans I, van Berge Henegouwen MI. Addressing patients' information needs: a first evaluation of a question prompt sheet in the pretreatment consultation for patients with esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:512–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown RF, Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH. Promoting patient participation and shortening cancer consultations: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1273–1279. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langbecker D, Janda M, Yates P. Development and piloting of a brain tumour-specific question prompt list. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2012;21:517–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44:1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. 1. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Davis SA, Watson CH, Lee C, Loughlin CE, Garcia N, Etheridge D, Rivera-Duchesne L, Reuland DS, Batey K, Duchesne C, Tudor G. Acceptance of a pre-visit intervention to engage teens in pediatric asthma visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:2005–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Lee C, Loughlin CE, Etheridge D, Rivera-Duchesne L, Reuland DS, Batey K, Duchesne CI, Garcia N, Tudor G. The development of an educational video to motivate teens with asthma to be more involved during medical visits and to improve medication adherence. J Asthma. 2016;53:714–719. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1135945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Slota C, Williams D, Tudor G, Yeatts K, Davis S, Ayala GX. Communication during pediatric asthma visits and self-reported asthma medication adherence. Pediatrics. 2012;130:627–633. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bursch B, Schwankovsky L, Gilbert J, Zeiger R. Construction and validation of four childhood asthma self-management scales: parent barriers, child and parent self-efficacy, and parent belief in treatment efficacy. J Asthma. 1999;36:115–128. doi: 10.3109/02770909909065155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhee H, Belyea MJ, Ciurzynski S, Brasch J. Barriers to asthma self-management in adolescents: Relationships to psychosocial factors. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:183–191. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Publication Number 97-4051. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. [Accessed Dec 1 2017];Expert panel report. 1997 2 http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/asthgdln_archive.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Publication Number 08-5846. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. [Accessed Dec 1 2017];Expert panel report. 2007 3 http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/asthsumm.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butz AM, Walker JM, Pulsifer M, Winkelstein M. Shared decision making in school age children with asthma. Pediatr Nurs. 2007;33:111–116. None. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system of the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Accessed Dec 1 2017]. http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-A-New-Health-System-for-the-21st-Century.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrington J, Noble LM, Newman SP. Improving patients' communication with doctors: a systematic review of intervention studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:7–16. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roter D. The medical visit context of treatment decision-making and the therapeutic relationship. Health Expect. 2000;3:17–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2000.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–675. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roter D, Lipkin M, Jr, Korsgaard A. Sex differences in patients' and physicians' communication during primary care medical visits. Med Care. 1991;29:1083–1093. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199111000-00002. None. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]