Abstract

Background

The number of homeless people in Germany is increasing. Studies from multiple countries have shown that most homeless people suffer from mental illnesses that require treatment. Accurate figures on the prevalence of mental illness among the homeless in Germany can help improve care structures for this vulnerable group.

Methods

We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental illness among homeless people in Germany.

Results

11 pertinent studies published from 1995 to 2013 were identified. The overall study population consisted of 1220 homeless people. The pooled prevalence of axis I disorders was 77.4%, with a 95% confidence interval [95% CI] of [71.3; 82.9]. Substance-related disorders were the most common type of disorder, with a pooled prevalence of 60.9% [53.1; 68.5]. The most common among these was alcoholism, with a prevalence of 55.4% [49.2; 61.5]. There was marked heterogeneity across studies.

Conclusion

In Germany, the rate of mental illness requiring treatment is higher among the homeless than in the general population. The development and implementation of suitable care models for this marginalized and vulnerable group is essential if their elevated morbidity and mortality are to be reduced.

The correlation between mental illness and homelessness has been the subject of both sociopolitical discussion and psychiatric research since the early 20th century (1). International studies conducted in the last 20 years have found lifetime prevalence rates for mental illness of between 60% and 93.3% among the homeless (2– 6). For instance, one-month prevalence rates of between 8.1% and 58.5% have been found for alcohol dependency and between 2.8% and 42.3% for psychotic illnesses (7). These are associated with increased mortality due to, for example, suicide (8, 9) and substance abuse (10), an increased risk of serious somatic illness, particularly infectious diseases (11, 12), and increased rates of criminality (13– 15) and violence (16).

The extent to which figures from a meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental illness among homeless people in Western countries are comparable to the situation in Germany is limited. The meta-analysis found that the most common disorders were alcohol dependency at 8.1 to 58.5%, drug dependency at 4.5 to 54.2%, and psychotic illnesses at 2.8 to 42.3% (7). These figures must be interpreted in the context of factors relating to the cultures, societies, and medical care in the countries in which the research was conducted, as societal and social phenomena such as homelessness, poverty, and marginalization are dependent on countries‘ social orders.

In Germany there is no single, nationwide set of figures on homeless people. However, estimates by the German National Coalition of Service Providers for the Homeless (Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe) indicate that homelessness in Germany has increased substantially: in 2014 there were approximately 335 000 people in the country without a home of their own, representing an estimated 18% increase compared to 2012 (17). The German National Coalition of Service Providers for the Homeless expects an additional 200 000 increase to around 536 000 homeless people in Germany by 2018 (17), partly due to migration and refugee movements.

Reliable figures on the distribution of mental disorders among homeless people may provide political players, public bodies, and psychiatric facilities a basis for improvement of the urgently needed support options for this vulnerable group. The risk of an undersupply of medical care for homeless people with mental illness is high: Europe-wide, fewer than one-third receive treatment (18).

This article aims to provide an overview of German studies that have already been conducted on the prevalence of mental illness among the homeless in Germany, by means of a systematic search of the literature and a meta-analysis.

Method

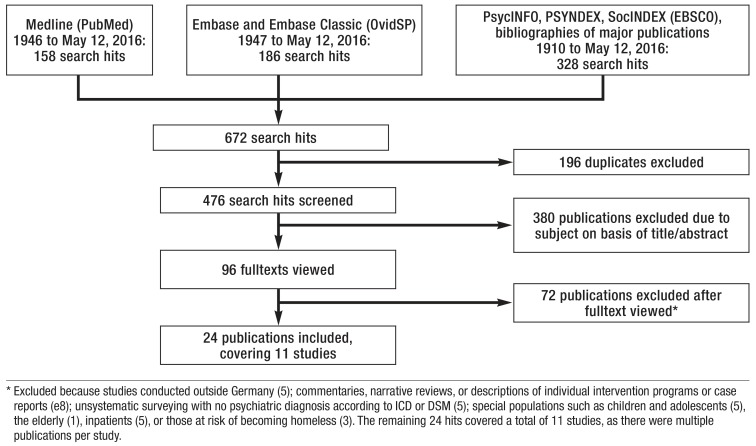

A systematic search of the literature for studies on the prevalence of mental illness among the homeless in Germany was performed via digital search platforms, using the search terms „homeless“ (or „homeless persons“) and „German“ (or „Germany“ or „Hamburg,“ „Berlin, “ „Munich“) (figure 1). Next, the bibliographies of major publications were searched and individual authors were contacted. The search of the literature was performed by a physician, aided by a librarian. Studies were evaluated by a physician.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram Literature search process

The following study inclusion criteria were used:

A definition of homelessness was stated; standardized diagnosis was conducted using ICD or DSM

Psychiatric diagnosis was performed via clinical examination based on validated diagnostic tools

With the exception of personality disorders, precise one-month prevalence rates were stated

Data was collected in Germany

There were various definitions of homelessness: from persons living directly on the streets only to other definitions that included those living in shelters for the homeless. Five studies used a time-based criterion, ranging from 30 days to 3 months.

Prevalence rates were calculated using a double arcsine transformation via MetaXL 5.3, which stabilizes variance (19). A random-effects model was used. The heterogeneity of the included studies was estimated using Cochran‘s Q and I2 and represented using 95% confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was further explored using subgroup analyses based on categorical variables (time data collected [beginning before or after 2000], study size [less or more than 100], sex [male or female], participation rate [less or more than 80%]). This procedure was based on the MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) criteria (20).

Results

We found 11 studies published between 1995 and 2013 (table 1) (2, 11, 12, 21– 40, e1). Data was collected between 1989 and 2012. The total population of all the studies was 1220 homeless people, 131 (10.7%) of whom were women. Six studies investigated male-only samples (11, 12, 21, 26, 28– 30, 32– 35, 38– 40), 2 female-only (22, 31, 37), and 3 studies investigated samples of both sexes (with women accounting for between 13.7 and 20.7% of individuals) (2, 23– 25, 27, 36, e1). The mean ages of the investigated homeless people ranged from 29 to 48.1 years. Five studies were conducted in Munich (n = 804) (2, 11, 27, 29, 31– 39, e1), two in Tübingen (n = 108) (22, 30), and one each in Berlin (n = 72) (28, 40), Münster (n = 52) (26), Mannheim (n = 102) (23– 25), and Dortmund (n = 82) (12, 21). For the longitudinal study conducted in Munich, analysis took account of when data was first collected (27, 36). All data was collected in large cities (population >100 000), with the exception of Tübingen. Table 1 provides an overview of sampling strategies, definitions of homelessness, participation rates, and measuring tools used.

Table 1. Details of included studies.

| Study | When data collected | Where data collected | Sample type | Definition of homelessness | Recruitment strategy | Sample size | Tools | Diagnostic criteria | Mean age (years) | Women (%) | Professional interviews | Participation rate (%) |

| Fichter, 1996, 1997, 1999 (32, 37, 39); Meller, 2000 (29) | 1989 to 90 | Munich | Representative random sample | No home for at least 30 days before interview | Common locations for the homeless | 146 | DIS-III, MMSE | DSM-III | 43 | 0 | No*2 | 85 |

| Greifenhagen 1997, (31); Meller, 2000 (29) | 1989 to 90 | Munich | Representative random sample | No home for at least 30 days before interview | Common locations for the homeless | 32 | DIS-III, MMSE | DSM-III | 35.5 | 100 | No*2 | 89 |

| Reker, 1997 (26) | 1990 | Münster | Data collected on all residents of a shelter for homeless men | >3 months living in city shelter | City shelter for homeless men | 52 | Semi-structured interview, GAF | ICD-10 | 45.0 | 0 | Yes | 78.8 |

| Podschus, 1995 (28); Dufeu, 1996 (40) | 1993 to 94 | Berlin | Random sample | Section 72 of the German FWA | City mission soup kitchen | 72 | CIDI*1, MMSE, GAF | ICD-10 | 40.5 | 0 | Not stated | 85 |

| Fichter, 2006 (36); Quadflieg, 2007 (27) | 1994 to 96 | Munich | Data collected longitudinally on all homeless people | (1) Accommodation in home of friends or relatives, (2) accommodation at emergency shelter, (3) accommodation in unusual places | Recruitment in line with accommodation | 129 | SCID, MMSE, FPI−R, GAF, SCL-90-R | DSM-IV | 44.4 | 15.5 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Fichter, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2005 (11, 33 to 35, 38) | 1994 to 96 | Munich | Representative random sample | No home for at least 30 days before interview | Common locations for the homeless | 265 | SCID, MMSE | DSM-IV | 44.7 | 0 | No*2 | 88 |

| Völlm, 2004 (12, 21) | 1996 | Dortmund | Representative random sample | „Literally homeless“ as defined by Rossi (e2) | Advice centers and city shelters | 82 | CIDI*1, AMDP | ICD-10 | 41.4 | 0 | Yes | 81.5 |

| Salize, 2001, 2002 (23, 24, e3) | 1997 to 99 | Mannheim | Representative random sample | No room or home | Common locations for the homeless | 102 | SCID, MLDL | DSM-IV | 40.0 | 13.7 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Torchalla, 2004 (22) | 2001 | Tübingen | Data collected on all homeless women | Section 72 of the German FWA | Advice centers, recruitment by professional support workers | 17 | SCID, BeLP | DSM-IV | 29 | 100 | Not stated | 77.3 |

| Längle, 2005 (30) | 2002 to 03 | Tübingen | Data collected on all appropriate individuals | Section 72 of the German FWA | Common locations for the homeless | 91 | SCID, BML, MMSE, MWT-B, WAIS-R, GAF, BeLP | ICD-10 | 40.0 | 0 | Yes | 60.3 |

| Brönner, 2013 (e1); Jahn 2014 (2) | 2010 to 12 | Munich | Representative random sample | Residents of homeless shelters | Facilities for the homeless | 232 | SCID, MALT, BDI, mini ICF-APP, SF-36, B-L, CGI, MMSE, WAIS | DSM-IV | 48.1 | 20.7 | Not stated | 55 |

*1Parts on dependency disorders and psychosomatic disorders; *2Trained laypeople

AMDP, Working Group for Methods and Documentation in Psychiatry (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Methodik und Dokumentation in der Psychiatrie); BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BeLP: Berlin Quality of Life Profile (Berliner Lebensqualitätsprofil); B-L: Complaints List (Beschwerdeliste): BML: Brunswick List of Features (Braunschweiger Merkmalsliste) for chronic, multiply-impaired alcoholics FWA: Federal Welfare Act; CGI: Clinical Global Impression Scale; CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS: Diagnostic Interview Schedule; FPI-R: Freiburg Personality Inventory (Freiburger Persönlichkeitsinventar) – Revision; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; WAIS-R: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revision; MALT: Munich Alcoholism Test (Münchner Alkoholismustest); Mini-ICF-APP: Mini-ICF-APP Social Functioning Scale; MLDL: Munich Quality of Life List (Münchner Lebensqualitäts-Dimensionen-Liste); MMSE: Mini-Mental Status Examination; MWT-B: Multiple-Choice Vocabulary Test (Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatztest), version B; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist 90 – Revised; SF-36: Short-Form Health Survey; WAIS: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

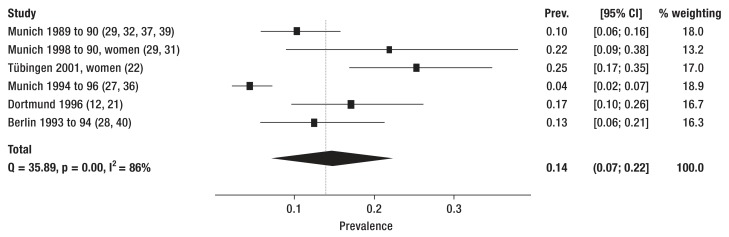

The pooled prevalence of mental illness was 77.5%, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] [72.4; 82.3] (11 studies). The corresponding figure for Axis I disorders was 77.4% [71.3; 82.9] (8 studies) (2, 11, 22, 30, 31, 36, 39, 40). In decreasing order, pooled prevalence rates were as follows: the most common disorders were substance-related disorders at 60.9% [53,1; 68,5] in 6 studies (22, 25, 31, 33, 36, 39), with 55.4% [49.2; 61.5] in 8 studies (21, 22, 25, 31, 32, 36, 38, 40) for alcohol dependency and 13,9% [7.2; 22.2] in 6 studies (21, 22, 31, 33, 39, 40) for drug dependency. The second-most common disorders were anxiety disorders, with a pooled prevalence of 17.6% [12.9; 22.8] in 6 studies (22, 31, 33, 36, 39), followed by affective disorders at 15.2% [9.8; 21.5] in 8 studies (21, 22, 24, 30, 31, 33, 39, 40), with major depression at 11.6% [4.4; 21.3] in 5 studies (22, 31, 33, 36, 39), and psychotic illnesses at 8.3% [5.4; 11.8] in 10 studies (21, 22, 24, 26, 30, 31, 33, 36, 39, 40). The pooled prevalence of cognitive impairment was 11.7% [6.0; 18.9] in 7 studies (21, 22, 31, 33, 36, 39, 40); that of personality disorders was 29.1% [5.6; 59.5] in 3 studies (2, 21, 24) (summarized in eTable 2 and Figures 2 to 4 eFigures 1 to 7).

eTable 2. Findings of subgroup analysis.

| Disorder type | Pooled prevalence (random-effects model) | Prevalence range | [95% confidence interval] | p | I2 [95% confidence interval] | No. of studies |

| All mental illness*1 | 77.5% | 65.1 to 93.8% | [72.4; 82.3] | 0.000 | 74.61 [53.98; 86.00] | 11 |

| Axis I disorders | 77.4% | 65.1 to 93.8% | [71.3; 82.9] | 0.000 | 75.93 [51.8; 87.98] | 8 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | 73.3% | 70.6 to 74.0% | [68.5; 77.9] | 0.898 | 0.00 [0.00; 3.24] | 3 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 80.6% | 56.7 to 93.8% | [71.1; 88.5] | 0.000 | 85.42 [67.78; 93.4] | 5 |

| Homeless women only | 83.3% | 70.6 to 93.8% | [56.9; 100.0] | 0.038 | 76.80 [0.00; 94.71] | 2 |

| Homeless men only | 76.6 % | 65.1 to 90.3% | [68.7; 83.7] | 0.000 | 80.87 [55.33; 91.81] | 5 |

| Participation rate >80% | 84.0% | 73.4 to 93.8% | [74.7; 91.6] | 0.001 | 81.90 [53.13; 93.01] | 4 |

| Participation rate <80% | 73.3% | 70.6 to 74.0% | [68.5; 77.9] | 0.000 | 0.00 [0.00; 3.24] | 3 |

| Sample size >100 | 73.6% | 65.1 to 80.8% | [68.0; 78.8] | 0.034 | 65.31 [0.00; 88.21] | 4 |

| Sample size <100 | 83.4% | 70.6 to 93.8% | [70.1; 93.5] | 0.004 | 77.71 [39.62; 91.77] | 4 |

| Interviewers: professional | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 81.5% | 73.4 to 93.8% | [71.4; 89.9] | 0.009 | 78.9 [32.48; 93.41] | 3 |

| Psychotic illnesses | 8.3% | 2.3 to 34.4% | [5.4; 11.8] | 0.002 | 65.50 [32.39; 82.40] | 10 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | 8.6% | 7.7 to 11.8% | [3.9; 14.7] | 0.486 | 0.00 [0.00; 0.00] | 2 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 8.2% | 2.3 to 34.4% | [4.9; 12.2] | 0.001 | 72.31 [43.22; 86.50] | 8 |

| Homeless women only | 23.1% | 11.8 to 34.4% | [5.0; 47.7] | 0.090 | 76.80 [0.00; 92.08] | 2 |

| Homeless men only | 7.6% | 4.9 to 9.6% | [5.8; 9.7] | 0.791 | 0.00 [0.00; 47.19] | 6 |

| Participation rate >80% | 9.8% | 4.9 to 34.4% | [4.9; 16.0] | 0.002 | 77.05 [44.38; 90.53] | 5 |

| Participation rate <80% | 6.6% | 2.3 to 11.8% | [3.5; 10.5] | 0.135 | 43.01 [0.00; 79.06] | 5 |

| Sample size >100 | 6.2% | 2.3 to 9.6% | [3.6; 9.5] | 0.076 | 56.32 [0.00; 85.52] | 4 |

| Sample size <100 | 10.8% | 4.9 to 34.4% | [5.4; 17.8] | 0.007 | 68.97 [26.91; 86.83] | 6 |

| Interviewers: professional | 7.4% | 4.9 to 9.6% | [4.3; 11.2] | 0.553 | 0.00 [0.00; 82.46] | 3 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 12.9% | 6.6 to 34.4% | [4.2; 25.1] | 0.000 | 87.4 [64.18; 95.54] | 3 |

| Affective disorders | 15.2% | 5.6 to 46.9% | [9.8; 21.5] | 0.000 | 82.66 [67.18; 90.84] | 8 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 15.8% | 5.6 to 46.9% | [9.6; 23.1] | 0.000 | 84.71 [70.30; 92.13] | 7 |

| Homeless women only | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Homeless men only | 14.6% | 5.6 to 24.0% | [9.4; 20.6] | 0.004 | 73.88 [35.04; 89.5] | 5 |

| Participation rate >80% | 19.2% | 5.6 to 46.9% | [10.9; 29.0] | 0.000 | 85.32 [67.52; 93.36] | 5 |

| Participation rate <80% | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Sample size >100 | 14.1% | 6.9 to 24.0% | [8.2; 21.2] | 0.001 | 81.63 [52.29; 92.93] | 4 |

| Sample size <100 | 16.5% | 5.6 to 46.9% | [5.4; 31.4] | 0.000 | 87.46 [70.1; 94.74] | 4 |

| Interviewers: professional | 13.4% | 11.0 to 15.9% | [8.7; 18.9] | 0.353 | 0.00 [0.00; 0.00] | 2 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 25.9% | 16.3 to 46.9% | [14.0; 39.7] | 0.001 | 86.31 [60.44; 95.26] | 3 |

| Major depression | 11.6% | 0.00 to 40.6% | [4.4; 21.3] | 0.000 | 87.47 [73.15; 94.15] | 5 |

| Substance-related disorders | 60.9% | 47.1 to 74.0% | [53.1; 68.5] | 0.003 | 72.60 [36.88; 88.10] | 6 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 62.1% | 51.9 to 74.0% | [53.9; 69.9] | 0.002 | 75.98 [41.24; 90.18] | 5 |

| Homeless women only | 58.3 % | 47.1 to 65.6 % | [40.4; 75.2] | 0.220 | 33.54 [0.00; 0.00] | 2 |

| Homeless men only | 68.5 % | 63.0 to 74.0 % | [57.2; 78.7] | 0.023 | 80.71 [17.52; 95.49] | 2 |

| Participation rate >80% | 67.7 % | 63.0 to 74.0 % | [59.3; 75.6] | 0.073 | 61.73 [0.00; 89.08] | 3 |

| Participation rate <80% | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Sample size >100 | 61.6 % | 51.9 to 74.0 % | [52.3; 70.5] | 0.001 | 81.90 [53.01; 93.00] | 4 |

| Sample size <100 | 58.3 % | 47.1 to 65.6 % | [40.4; 75.2] | 0.220 | 33.54 [0.00; 0.00] | 2 |

| Interviewers: professional | / | / | / | / | / | 0 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 67.7 % | 63.0 to 74.0 % | [59.3; 75.6] | 0.073 | 61.73 [0.00; 89.08] | 3 |

| Alcohol dependency | 55.4 % | 43.1 to 68.1 % | [49.2; 61.5] | 0.002 | 69.66 [36.82; 85.43] | 8 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 55.6 % | 43.1 to 68.1 % | [48.5; 62.5] | 0.001 | 73.72 [43.74; 87.73] | 7 |

| Homeless women only | 52.0 % | 46.9 to 53.8 % | [43.2; 60.8] | 0.503 | 0.00 [0.00; 0.00] | 2 |

| Homeless men only | 61.2 % | 51.2 to 68.1 % | [54.2; 68.0] | 0.051 | 61.30 [0.00; 87.03] | 4 |

| Participation rate >80% | 59.6 % | 46.9 to 68.1 % | [52.7; 66.4] | 0.038 | 60.58 [0.00; 85.23] | 5 |

| Participation rate <80% | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Sample size >100 | 55.1 % | 43.1 to 67.1 % | [45.6; 64.4] | 0.001 | 82.08 [53.71; 93.06] | 4 |

| Sample size <100 | 55.8 % | 46.9 to 68.1 % | [47.0; 64.4] | 0.097 | 52.52 [0.00; 84.31] | 4 |

| Interviewers: professional | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 59.7 % | 46.9 to 67.1 % | [50.8; 68.4] | 0.061 | 64.28 [0.00; 89.76] | 3 |

| Drug dependency | 13.9 % | 4.4 to 25.3 % | [7.2; 22.2] | 0.000 | 86.07 [71.78; 93.12] | 6 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 11.7 % | 4.4 to 21.9 % | [6.0; 18.8] | 0.000 | 80.14 [53.26; 91.56] | 5 |

| Homeless women only | 24.6 % | 21.9 to 25.3 % | [17.4; 32.6] | 0.746 | 0.00 [0.00; 0.00] | 2 |

| Homeless men only | 10.1 % | 4.4 to 17.1 % | [4.8; 16.9] | 0.002 | 80.27 [47.92; 92.52] | 4 |

| Participation rate >80% | 11.7 % | 4.4 to 21.9 % | [6.0; 18.8] | 0.000 | 80.14 [53.26; 91.56] | 5 |

| Participation rate <80% | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Sample size >100 | 6.5 % | 4.4 to 10.3 % | [1.9; 13.5] | 0.025 | 80.06 [14.29; 95.36] | 2 |

| Sample size <100 | 19.1 % | 12.5 to 25.3 % | [13.6; 25.3] | 0.203 | 34.85 [0.00; 77.23] | 4 |

| Interviewers: professional | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 9.6 % | 4.4 to 21.9 % | [3.0; 19.0] | 0.003 | 83.30 [49.35; 94.49] | 3 |

| Anxiety disorders | 17.6 % | 11.6 to 35.3 % | [12.9; 22.8] | 0.034 | 58.66 [0.00; 83.23] | 6 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | 23.7 % | 18.7 to 35.3 % | [9.7; 41.0] | 0.139 | 54.38 [0.00; 88.82] | 2 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 15.8 % | 11.6 to 28.1 % | [11.1; 21.1] | 0.072 | 57.06 [0.00; 85.75] | 4 |

| Homeless women only | 30.9 % | 28.1 to 35.3 % | [18.7; 44.6] | 0.598 | 0.00 [0.00; 0.00] | 2 |

| Homeless men only | 14.1 % | 11.6 to 18.7 % | [10.5; 18.1] | 0.232 | 31.46 [0.00; 92.87] | 3 |

| Participation rate >80% | 15.3 % | 11.6 to 28.1 % | [9.3; 22.3] | 0.062 | 64.08 [0.00; 89.71] | 3 |

| Participation rate <80% | 23.7 % | 18.7 to 35.3 % | [9.7; 41.0] | 0.139 | 54.38 [0.00; 88.82] | 2 |

| Sample size >100 | 14.1 % | 11.6 to 17.8 % | [10.7; 17.9] | 0.240 | 29.96 [0.00; 92.72] | 3 |

| Sample size <100 | 24.3 % | 18.7 to 35.3 % | [15.4; 34.3] | 0.235 | 30.98 [0.00; 92.82] | 3 |

| Interviewers: professional | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 15.3 % | 11.6 to 28.1 % | [9.3; 22.3] | 0.062 | 64.08 [0.00; 89.71] | 3 |

| Cognitive deficit*2 | 11.7 % | 0.00 to 35.2 % | [6.0; 18.9] | 0.000 | 86.65 [74.68; 92.96] | 7 |

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||

| Data collected from 2000 onwards | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Data collected before 2000 | 9.5 % | 0.00 to 15.3 % | [6.2; 13.3] | 0.033 | 58.89 [0.00; 83.32] | 6 |

| Homeless women only | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Homeless men only | 15.5 % | 8.9 to 35.2 % | [8.2; 24.6] | 0.000 | 87.08 [72.15; 94.01] | 5 |

| Participation rate >80% | 9.8 % | 0.00 to 15.3 % | [5.8; 14.6] | 0.024 | 64.56 [6.90; 86.51] | 5 |

| Participation rate <80% | / | / | / | / | / | 1 |

| Sample size >100 | 9.2 % | 7.4 to 9.9 % | [6.9; 11.7] | 0.746 | 0.00 [0.00; 64.44] | 3 |

| Sample size <100 | 13.2 % | 0.00 to 35.2 % | [2.3; 29.7] | 0.000 | 90.37 [78.32; 95.72] | 4 |

| Interviewers: professional | 23.1 % | 14.6 to 35.2 % | [5.7; 46.4] | 0.002 | 89.83 [62.50; 97.24] | 2 |

| Interviewers: non-professional | 6.8 % | 0.00 to 9.99 % | [2.6; 12.6] | 0.040 | 68.98 [0.00; 90.97] | 3 |

| Personality disorders | 29.1 % | 14.7 to 55.1 % | [5.6; 59.5] | 0.000 | 96.84 [93.57; 98.45] | 3 |

*1Some studies reported point prevalences of mental illness, including personality disorders, with no further differentiation of Axis I disorders. Others reported only Axis I disorders and did not record information on personality disorders. Total mental illness summarizes all 11 studies and covers all reported mental illness, regardless of whether a distinction was made between Axis I and Axis II disorders. *2Based on the Mini-Mental Status Examination.

Figure 2.

Forest plot (random-effects model): All mental illness. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Figure 4.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Alcohol dependency. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

eFigure 1.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Axis I disorders. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

eFigure 7.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Personality disorders. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Overall heterogeneity was high (I2 ranged from 58.66% to 96.84%, Q from 12.09 to 63.36). Subgroup analysis shed further light on individual factors (etable 2).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of mental illness among the homeless in Germany included 11 studies, covering 1220 individuals. We found a prevalence of alcohol dependency 1.5 times higher than in other Western countries (including the USA, the United Kingdom, and Australia) (55.4% [49.2; 61.5] versus 37.9% [27.8; 48.0]) (7). Prevalence rates of psychotic illnesses and drug dependency were lower than in other Western countries (table 2).

Table 2. Point prevalences of mental illnesses.

| Illness |

This meta- analysis |

Meta-analysis of Western countries by Fazel et al. (7) |

General German population (e4) |

| Axis I disorders | 77.4% | – | 19.8% |

| Substance-related disorders | 60.9% | – | 2.9% |

| Alcohol dependency | 55.4% | 37.9% | 2.5%*1 |

| Drug dependency | 13.9% | 24.4% | 0.5%*1 |

| Affective disorders | 15.2% | – | 6.3% |

| Major depression | 11.6% | 11.4% | 5.6%*2 |

| Psychotic illnesses | 8.3% | 12.7% | 1.5%*3 |

| Anxiety disorders | 17.6% | – | 9.0% |

*11-month prevalence of dependency and abuse combined

*2 1-month prevalence of all unipolar depression

*3 Screening for schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses with no further differential diagnosis, also includes psychotic symptoms in affective disorders

The German National Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1, Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland), conducted between 2008 and 2011 in a sample representative of the population, found a one-month prevalence rate of DSM-IV disorders of 19.8% (e4). Our data on the homeless thus yielded a mental illness rate 3.8 times higher than in the general population. This includes all disorder spectra (table 2). The prevalence of substance-related disorders was 21 times higher than in the general population (2.9%) (e4), and that of alcohol dependency was 22 times higher. In the general population the rate of alcohol dependency and alcohol abuse combined was 2.5% (e4).

There are 3 possible models that might explain the substantially higher rates of alcohol dependency:

The fact that the support system is partly based on abstinence makes it harder for those particularly at risk to access: numerous international studies on the housing-first concept (e5) show that low-threshold accommodation and support that accepts alcohol consumption enable homeless people to be taken off the streets.

The availability and price regulation of addictive drugs, which in Germany depends on comparatively low alcohol prices, may be an additional factor. In contrast, the rates of dependency on other substances such as crack or other stimulants are significantly higher in North America than among German homeless people (e6). Alcohol, meanwhile, is comparatively expensive there, and its use among the homeless is less widespread (e6).

The consumption of psychotropic substances is a major coping strategy among those who are marginalized and have few other resources to solve their problems and very little access to the support system (e7).

The extent to which mental illness or substance abuse and homelessness are interrelated is a subject of ongoing discussion. It seems uncontroversial that each affects the other. A recently published meta-analysis of US veterans suggests that mental illness and substance abuse are the most consistent risk factors for becoming homeless (e8). Both substance abuse and homelessness can be associated with increased mortality: Tsai et al. report alcohol-associated mortality between 3 and 5 times higher, and drug-associated mortality between 8 and 17 times higher, among the homeless than in the general population (e9). Canadian data also shows that mental illness and substance abuse are associated with becoming homeless at an early age (e10).

This research yielded a pooled prevalence of 11.7% [6.0; 18.9] for significant cognitive deficits. Limited cognitive function, for example due to traumatic brain injury, is widespread among the homeless (e11). Tsai et al. also identified cognitive deficits as an important risk factor for homelessness (e9). Thus both severe substance abuse and traumatic brain injury increase the probability of cognitive deficits (e6).

Subgroup analysis revealed interesting findings for individual subgroups of homeless individuals. One important factor is sex. Only 131 (10.7%) of the total of 1220 homeless people were female. Our subgroup analyses found particularly high prevalence rates in studies involving only female homeless people for all Axis I disorders (83.3% [56.9; 100.0] versus 76.6% [68.7; 83.7]), psychotic illnesses (23.1% [5.0; 47.7] versus 7.6% [5.8; 9.7]), and drug dependency (24.6% [17.4; 32.6] versus 10.1% [4.8; 16.9]). This means that females are a particularly at-risk group. Although there was only one study in female homeless people that examined affective disorders, this also showed a higher prevalence rate, 46.9%, than in male homeless people only (14.6% [9.4; 20.6]). There were lower prevalence rates among homeless women compared to men for substance-related disorders and alcohol dependency. Homeless women are a subgroup that may be confronted with particular difficulties: estimated numbers of unreported homeless women are particularly high, as women are less likely to live directly on the streets and more likely to live in the homes of acquaintances, so their homelessness is more likely to go undetected, and they often do not use the available support system (e12, e13). As a result, homeless women are more frequently confronted with difficulties such as dependency on others and lack of safeguards (e12, e13). Because study sampling focused mainly on homeless people on the streets or in homeless shelters, homeless women have not yet been sufficiently researched.

In studies with participation rates above 80% only, the prevalence of Axis I disorders was 84.0% [74.7; 91.6] (versus 73.3% [68.5; 77.9] for studies with participation rates below 80%). There was a similar trend for psychotic illnesses (prevalence 9.8% [4.9; 16.0] for participation rates above 80% versus 8.6% [3.5; 10.5] for participation rates below 80%). Fazel et al. found a comparable correlation between high participation rates and high prevalences of depressive disorders and personality disorders (7, e14). The explanation for this correlation may be a refusal to participate in studies by individuals with more severe symptoms (7, e14). The correlation between lower prevalence rates and low participation rates suggests that homeless people should be investigated particularly thoroughly, e.g. via repeat questionnaires or data collection from other, additional sources (7).

Subgroup analyses for time of data collection (2000 onwards) highlight the lack of recent studies. The pooled prevalence of Axis I disorders in studies conducted after 2000 was lower than in older studies (73.3% [68.5; 77.9] versus 80.6% [71.1; 88.5]). However, the prevalence of psychotic illnesses was slightly higher in studies conducted after 2000 (8.6% [3.9; 14.7] versus 8.2% [4.9; 12.2]). This supports the idea put forward by some authors that psychotic illnesses have increased over time among homeless people due to factors such as dehospitalization (e15, e16).

Pooled prevalence rates were almost all lower in studies with sample size above 100 participants only than in studies with smaller case numbers. This was true of Axis I disorders, psychotic illnesses, affective disorders, alcohol and drug dependency, anxiety disorders, and cognitive disorders. It therefore seems advisable to interpret studies with lower case numbers cautiously in general, as they may indicate falsely high prevalence rates.

Outlook

This research raises several questions which might be addressed in future studies on homelessness in Germany:

Studies on this subject do not have a uniform definition of homelessness. Some studies have investigated only people living on the streets; others have also included those living in homeless shelters. We consider it appropriate for future work to be guided by the definition laid down by the European Commission, which includes all people with no fixed address (e17).

Studies have not included enough homeless women: the majority have investigated all-male populations, which makes it difficult to take sufficient account of the needs of homeless women. Only 10.7% of the total of 1220 homeless people were female.

Non-German-speaking homeless people, and therefore refugees and those with a background of migration, remain underresearched.

In addition, sample sizes are often small, and the data collection tools used vary. This makes comparison difficult. Personality disorders were examined in only 3 studies (2, 12, 21, 24, 25).

One limitation of our analysis is the fact that multiple studies were conducted in Munich. It is therefore possible that individual participants may have been included in studies more than once. (Study intervals were between 4 and 14 years.) In addition, all the studies were conducted in towns and cities, where the risk of mental illness is generally higher than in rural areas (e18).

Social marginalization and homelessness are a highly charged, growing problem among those with mental issues. There is an urgent need for social, political, and psychiatric bodies to develop care models for this at-risk group. International studies have found assertive community treatment (ACT) programs that provide an intensive level of care directly on the streets or in homeless shelters, and intensive case management (ICM) programs, particularly beneficial in caring for homeless people with mental illness (e5, e19). Critical factors in care are strategies involving reach-out programs and a continuous active contact, as tailored and low-threshold support are especially important for this particularly at-risk group. An example of the use of such low-threshold support that involves visiting individuals is the „Mainz Model,“ which operates according to the principle, „if the patient doesn‘t come to the doctor, the doctor must go to the patient“ (e20). This approach can also be used to prevent homelessness: models in Mannheim and Freiburg have shown that early referral of individuals at risk of becoming homeless for specialized psychiatric treatment led to improved quality of life and social support (e21). The mortality and need for urgent care of homeless people is increased not only by mental illness, examined here, but also by somatic illness. Both comprise an important subject for research and care (11). Access to treatment is a particularly severe problem.

A recently published EU study of access to the support system for socially marginalized groups identified the following factors as particularly requiring improvements in care:

Work visiting homeless people in communities

Support aimed at preventing emergencies, in order to reduce the burden on acute hospital care

Improvements in interfacing problems

More intensive community relations (e22)

In this context, it seems particularly important to evaluate international experiences as bases for further work and to discuss care models and the extent to which they can be transferred to other settings.

Figure 3.

Forest plot (random-effects model): substance-related disorders. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Key Messages.

In Germany, homeless people are substantially more likely than the general population to suffer from mental illness that requires treatment.

The most common mental illnesses are substance-related disorders, particularly alcohol dependency.

Research into homeless women and people with a background of migration is particularly difficult methodologically and is therefore underrepresented.

Study heterogeneity is high. This makes a single definition of homelessness and representative data collection necessary in future research.

It would be worthwhile to implement intervention programs and studies and to conduct longitudinal research into homeless people in Germany.

eFigure 2.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Psychotic illnesses. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

eFigure 3.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Affective disorders. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

eFigure 4.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Drug dependency. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

eFigure 5.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Anxiety disorders. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

eGrafik 6.

Forest plot (random-effects model): Cognitive deficit. Prev.: Prevalence; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

eTable 1. Details of included studies.

| Study | When data collected | Where data collected | Sample type | Definition of homelessness | Recruitment strategy | Accommodation status | Sample size | Tools | Diagnostic criteria | Mean age | Percentage female | Professional interviewer | Participation rate, % |

| Fichter, 1996, 1997, 1999 (32, 37, 39); Meller, 2000 (29) | 1989 to 1990 | Munich (male participants only) | Representative random sample | No home in Munich area for at least 30 days before interview | Common locations for the homeless (soup kitchens, emergency shelters, outdoor locations, etc.) | 3 categories: I. outdoors (49) II. with beds (25) III. meals/advice (72) |

146 | DIS-III, MMSE | DSM-III | 43 | 0 | No*2 | 85 |

| Greifenhagen, 1997(31); Meller, 2000 (29) | 1989 to 1990 | Munich (female participants only) | Representative random sample | No home in Munich area for at least 30 days before interview (except women‘s shelters) | Common locations for the homeless (soup kitchens, emergency shelters, outdoor locations, etc.) | 3 categories: I. outdoors (12) II. with beds (14) III. meals/advice (6) |

32 | DIS-III, MMSE | DSM-III | 35.5 | 100 | No*2 | 89 |

| Reker, 1997 (26) | 1990 | Münster | Data collected on all residents of a shelter for homeless men (stay >3 months) | >3 months living in city shelter | City shelter for homeless men | City shelter for homeless men (52) | 52 | Semi-structured interview, GAF | ICD-10 | 45.0 | 0 | Yes | 78.8 |

| Podschus, 1995 (28); Dufeu, 1996 (40) | 1993 to 1994 | Berlin | Random sample (restaurant for the homeless) | Section 72 of the German FWA: homelessness due to social situation | City mission soup kitchen | Sleeping rough (25), boarding houses (46), with friends (8), emergency accommodation (3), hostel (3), sheltered accommodation (2) |

72 | CIDI*1, MMSE, GAF | ICD-10 | 40.5 | 0 | Not stated | 85 |

| Fichter, 2006 (36); Quadflieg, 2007 (27) | 1994 to 1996 | Munich | Data collected longitudinally on all homeless people in line with allocation of living space | At least one of the following in the last 30 days: (1) accommodation in home of friends or relatives with at least 3 changes of accommodation, (2) accommodation at emergency shelter for the homeless, (3) accommodation in places not intended as such (e.g. parks) | Recruitment in line with accommodation (homes with therapeutic assistance, homeless shelters, social housing) | No information on previous housing status, at time of questioning in homes with therapeutic assistance (6), homeless shelters (75), social housing (13) | 129 | SCID, MMSE, FPI-R (emotional lability scale), GAF, SCL-90-R (scales: compulsiveness, insecurity on social contact, depression, anxiety, aggression, hostility) | DSM-IV | 44.4 | 15.5 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Fichter, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2005 (11, 33 to 35, 38) | 1994 to 1996 | Munich | Representative random sample | No home in Munich area for at least 30 days before interview | Common locations for the homeless (soup kitchens, emergency shelters, outdoor locations, etc.) | 3 categories: I. outdoors (12) II. with beds (158) III. meals/advice (95) |

265 | SCID, MMSE | DSM-IV | 44.7 | 0 | No*2 | 88 |

| Völlm, 2004 (12, 21) | 1997 to 1999 | Mannheim | repräsentative Zufallsstichprobe | No room or home on basis of rent agreement (refugees excluded) | Common locations for the homeless (streets, shelters, soup kitchens, advice centers) | 3 categories: I. sleeping rough (18) II. homes and shelters for the homeless (66) III. hostels providing rehabilitation/therapy (18) |

102 | SCID, MLDL, physical examination | DSM-IV | 40.0 | 13,7 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Salize, 2001, 2002 (23, 24, e3) | 1996 | Dortmund | Representative random sample | Only „literally homeless“ as defined by Rossi (e2) | Advice centers and city shelters | „Sleeping rough“ (82) | 82 | CIDI*1, semi-structured interview in line with AMDP, physical examination | ICD-10 | 41.4 | 0 | Yes | 81.5 |

| Torchalla, 2004 (22) | 2001 | Tübingen | Data collected on all homeless women in Tübingen | Section 72 of German FWA: persons without adequate or permanent accommodation, extended to less obvious forms, e.g. shared accommodation | Advice centers, recruitment by professional support workers | Hospital (1), motor home (2), friends/acquaintances (6), women‘s shelter (5), assigned accommodation (2) | 17 | SCID, BeLP | DSM-IV | 29 | 100 | Not stated | 77.3 |

| Längle, 2005 (30) | 2002 to 2003 | Tübingen | Data collected on all appropriate individuals | Section 72 of German FWA: persons without adequate or permanent accommodation | Common locations for the homeless (soup kitchens, emergency shelters, outdoor locations, etc.), recruitment by professional support workers | Homeless shelters and emergency accommodation | 91 | SCID, BML, MMSE, MWT-B, WAIS-R, GAF, BeLP | ICD-10 | 40.0 | 0 | Yes | 60. 3 |

| Brönner, 2013 (e1); Jahn 2014 (2) | 2010 to 2012 | Munich | Representative random sample | Residents of homeless shelters in Munich and surrounding areas (long-term assistance, reintegration, low-threshold assistance, assistance in line with Section 53 et seq. of SSC XII, counseling/emergency accommodation, sheltered accommodation) | Facilities for the homeless in Munich and surrounding areas | Long-term assistance (61), housing according to Section 53 (52), low-threshold assistance (40), reintegration (32), emergency accommodation (28), sheltered accommodation complexes (19) | 232 | SCID, MALT, BDI, mini ICF-APP, SF-36, B-L, CGI, MMSE, WAIS | DSM-IV | 48.1 | 20,7 | Not stated | 55 |

*1Parts on dependency disorders and psychosomatic disorders; *2Trained laypeople

AMDP, Working Group for Methods and Documentation in Psychiatry (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Methodik und Dokumentation in der Psychiatrie); BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BeLP: Berlin Quality of Life Profile (Berliner Lebensqualitätsprofil); B-L: Complaints List (Beschwerdeliste): BML: Brunswick List of Features (Braunschweiger Merkmalsliste) for chronic, multiply-impaired alcoholics FWA: Federal Welfare Act; CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CGI: Clinical Global Impression Scale; DIS: Diagnostic Interview Schedule; FPI-R: Freiburg Personality Inventory (Freiburger Persönlichkeitsinventar) – Revision; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; WAIS-R: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revision; MALT: Munich Alcoholism Test (Münchner Alkoholismustest); Mini-ICF-APP: Mini-ICF-APP Social Functioning Scale; MLDL: Munich Quality of Life List (Münchner Lebensqualitäts-Dimensionen-Liste); MMSE: Mini-Mental Status Examination; MWT-B: Multiple-Choice Vocabulary Test (Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatztest), version B; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist 90 – Revised; SF-36: Short-Form Health Survey; SSC: Social Security Code; WAIS: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We would like to express particular gratitude to Prof. Seena Fazel, University of Oxford, UK, for his support in performing the meta-analysis.

We would like to thank Gabriele Menzel of the Charité Library for her help in performing the systematic search of the literature.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

References

- 1.Garcia C. Karl Wilmanns und die Landstreicher. Nervenarzt. 1986;57:227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klinikum rechts der Isar Jahn T, Brönner M. Die SEEWOLF-Studie - eine Zusammenfassung. www.mri.tum.de/sites/www.mri.tum.de/files/pressemeldungen/seewolf-studie_-_eine_zusammenfassung_0.pdf. (last accessed on 3 July 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vazquez C, Munoz M, Sanz J. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R mental disorders among the homeless in Madrid: a European study using the CIDI. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrman H, McGorry P, Bennett P, van Riel R, Singh B. Prevalence of severe mental disorders in disaffiliated and homeless people in inner Melbourne. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:1179–1184. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen SF, Hjorthøj CR, Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M. Psychiatric disorders and mortality among people in homeless shelters in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:2205–2214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60747-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koegel P, Burnam MA, Farr RK. The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among homeless individuals in the inner city of Los Angeles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1085–1092. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in Western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:1670–1681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prigerson HG, Desai RA, Liu-Mares W, Rosenheck RA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in homeless mentally ill persons: age-specific risks of substance abuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0621-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babidge NC, Buhrich N, Butler T. Mortality among homeless people with schizophrenia in Sydney, Australia: a 10-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:105–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrow SM, Herman DB, Córdova P, Struening EL. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:529–534. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichter M, Quadflieg N, Cuntz U. Prävalenz körperlicher und seelischer Erkrankungen. Dtsch Arztebl. 2000;97:A-1148–A-1154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Völlm B, Becker H, Kunstmann W. Prävalenz körperlicher Erkrankungen, Gesundheitsverhalten und Nutzung des Gesundheitssystems bei alleinstehenden wohnungslosen Männern: eine Querschnittsuntersuchung. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin. 2004;49:42–50. doi: 10.1007/s00038-003-3064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fazel S, Grann M. The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. Am J Psych. 2006;163:1397–1403. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan P, Mednick S, Hodgins S. Major mental disorders and criminal violence in a Danish birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:494–500. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelberg L, Linn L, Leake B. Mental health, alcohol and drug use, and criminal history among homeless adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:191–196. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh E, Moran P, Scott C, et al. Prevalence of violent victimisation in severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 20031;832:33–39. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe. Zahl der Wohnungslosen in Deutschland. www.bagw.de/de/themen/zahl_der_wohnungslosen/index.html (last accessed on 21 March 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canavan R, Barry MM, Matanov A, et al. Service provision and barriers to care for homeless people with mental health problems across 14 European capital cities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroup DF. MOOSE Statement: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283 doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Völlm B, Becker H, Kunstmann W. Psychiatrische Morbidität bei allein stehenden wohnungslosen Männern. Psychiatr Prax. 2004;31:236–240. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-815014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torchalla I, Albrecht F, Buchkremer G, Längle G. Wohnungslose Frauen mit psychischer Erkrankung - eine Feldstudie. Psychiatr Prax. 2004;31:228–235. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-814819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salize HJ, Horst A, Dillmann-Lange C, et al. Wie beurteilen psychisch kranke Wohnungslose ihre Lebensqualität? Psychiatr Prax. 2001;28:75–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salize HJ, Horst A, Dillmann-Lange C, et al. Needs for mental health care and service provision in single homeless people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s001270170065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salize HJ, Dillmann-Lange C, Stern G, et al. Alcoholism and somatic comorbidity among homeless people in Mannheim, Germany. Addiction. 2002;97:1593–1600. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reker T, Eikelmann B, Folkerts H. Prävalenz psychischer Störungen und Verlauf der sozialen Integration bei wohnungslosen Männern. Gesundheitswesen. 1997;59:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quadflieg N, Fichter M. Ist die Zuweisung dauerhaften Wohnraums an Obdachlose eine effektive Maßnahme? Eine prospektive Studie über drei Jahre zum Verlauf pschischer Beschwerden. Psychiatr Prax. 2007;34:276–282. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podschus J, Dufeu P. Alkoholabhängigkeit unter wohnungslosen Männern in Berlin. Sucht. 1995;41:348–354. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meller I, Fichter M, Quadflieg N, Koniarczyk M, Greifenhagen A, Wolz J. Die Inanspruchnahme medizinischer und psychosozialer Dienste durch psychisch erkrankte Obdachlose: Ergebnisse einer epidemiologischen Studie. Nervenarzt. 2000;71:543–551. doi: 10.1007/s001150050624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Längle G, Egerter B, Albrecht F, Petrasch M, Buchkremer G. Prevalence of mental illness among homeless men in the community: approach to a full census in a southern German university town. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:382–390. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0902-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greifenhagen A, Fichter M. Mental illness in homeless women: an epidemiological study in Munich, Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247:162–172. doi: 10.1007/BF03033070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fichter M, Quadflieg N, Greifenhagen A, Koniarczyk M, Wölz J. Alcoholism among homeless men in Munich, Germany. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:64–74. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)89644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fichter M, Quadflieg N. Prevalence of mental illness in homeless men in Munich, Germany: results from a representative sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:94–104. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fichter M, Quadflieg N. Course of alcoholism in homeless men in Munich, Germany: results from a prospective longitudinal study based on a representative sample. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:395–427. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fichter M, Quadflieg N. Three year course and outcome of mental illness in homeless men: a prospective longitudinal study based on a representative sample. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:111–120. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fichter M, Quadflieg N. Intervention effects of supplying homeless individuals with permanent housing: a 3-year prospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fichter M, Quadflieg N. Psychische Erkrankung bei obdachlosen Männern und Frauen in München. Psychiatr Prax. 1999;26:76–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fichter M, Quadflieg N. Alcoholism in homeless men in the mid-nineties: Results from the Bavarian Public Health study on homelessness. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;249:34–44. doi: 10.1007/s004060050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fichter M, Koniarczyk M, Greifenhagen A, et al. Mental illness in a representative sample of homeless men in Munich, Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;246:185–196. doi: 10.1007/BF02188952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dufeu P, Podschus J, Schmidt LG. Alkoholabhängigkeit bei männlichen Wohnungslosen. Nervenarzt. 1996;67:930–934. doi: 10.1007/s001150050074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Brönner M, Baur B, Pitschel-Walz G, Jahn T, Bäuml J. Seelische Erkrankungsrate in den Einrichtungen der Wohnungslosenhilfe im Großraum München: die SEEWOLF-Studie. Arch für Wiss und Prax der sozialen Arbeit. 2013;1:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- E2.Rossi PH, Wright JD, Fisher GA, Willis G. The urban homeless: estimating composition and size. Science. 1987;235:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.2950592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Salize HJ, Dillmann-Lange C, Stern G, Stamm K, Rössler W, Henn F. Alcoholism and somatic comorbidity among homeless people in Mannheim, Germany. Addiction. 2002;97:1593–1600. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Jacobi F, Wittchen HU, Holting C, et al. Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS) Psychol Med. 2004,;34:597–611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Goering PN, Streiner DL, Adair C. The At Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: a pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a housing first intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1:1–18. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Krausz R, Strehlau V, Schuetz C. Obdachlos, mittellos, hoffnungslos - Substanzkonsum, psychische Erkrankungen und Wohnungslosigkeit: ein Forschungsbericht aus den USA und Kanada. Suchttherapie. 2016;17:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- E7.Khantzian EJ. Self-regulation and self-medication factors in alcoholism and the addictions. Similarities and differences. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1990;8:255–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Depp CA, Vella L, Orff HJ, Twamley EW. A quantitative review of cognitive functioning in homeless adults. J Nerv Ment Disord. 2015;203:126–131. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US Veterans Jack. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177–195. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Cambioli L, Krausz M. Are substance use and mental illness associated to an earlier onset of homelessness? Ment Health Fam Med. 2016;12:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- E11.Nikoo M, Gadermann A, To MJ, Krausz M, Hwang SW, Palepu A. Incidence and associated risk factors of traumatic brain injury in a cohort of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in 3 Canadian cities. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;32(4):E19–E26. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe e. V. BAG Informationen. Weibliche Wohnungsnot. www.bagw.de/media/doc/POS_03_Frauen_Wohnungslosigkeit_Wohnungsnot.pdf. (last accessed 21 March 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E13.Riege M. Frauen in Wohnungsnot Erscheinungsformen - Ursachenanalyse - Lösungsstrategien - Forderungen. Kinder und Frauen zuletzt?! Frauen Wohnungsnot VSH Verlag für Soz Hilfe. 1994;25:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- E14.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Lamb HR. Deinstitutionalization and the homeless mentally ill. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1984;35:899–907. doi: 10.1176/ps.35.9.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.North CS, Eyrich KM, Pollio DE, Spitznagel EL. Are rates of psychiatric disorders in the homeless population changing? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:103–108. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Europäische Kommission. Messung der Obdachlosigkeit in Europa 2007. http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=1998&langId=de (last accessed March 21st 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E18.Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, Kluge U, Galea S, Heinz A. Cities and mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:121–127. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Nelson G, Aubry T, Lafrance A. A review of the literature on the effectiveness of housing and support, assertive community treatment, and intensive case management interventions for persons with mental illness who have been homeless. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:350–361. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Trabert G. Medizinische Versorgung für wohnungslose Menschen - individuelles Recht und soziale Pflicht statt Exklusion. Gesundheitswesen. 2016;78:107–112. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-111011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Salize HJ, Arnold M, Uber E, Hoell A. Verbesserung der psychiatrischen Behandlungsprävalenz bei Risikopersonen vor dem Abrutschen in die Wohnungslosigkeit. Psychiatr Prax. 2017;44:21–28. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1552764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Priebe S, Matanov A, Schor R, et al. Good practice in mental health care for socially marginalised groups in Europe: a qualitative study of expert views in 14 countries. BMC Public Health BioMed Central. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]