Abstract

Background

The homeless are often in poor health, and their risk of premature death is three to four times that of the general population. This article is intended to provide an overview of the medical care of the homeless in Germany.

Methods

We selectively reviewed pertinent scientific and non-scientific publications from the years 2000–2017 that were retrieved from PubMed, from the reports of the German Homeless Aid Society (Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe), from the websites of homeless aid organizations, and from Google Scholar.

Results

At least 75% of the homeless currently suffer from a mental illness requiring treatment. Common somatic problems include respiratory (6–14%) and cardiovascular disorders (7–20%), injuries and intoxications (5–15%), and infectious and parasitic diseases (10–16%). To circumvent the multiple barriers impeding homeless people’s access to standard medical care (lack of health insurance, a feeling of being unwelcome, lack of disease awareness, impaired capacity for compliance), medical help is offered to them outside the system in a number of ways, embedded in an overall scheme of social and practical assistance with daily living. These medical resources differ from region to region. They are often underfinanced and tend to focus on acute general medical care, with limited access to specialists.

Conclusion

More heath care resources need to be made available to the homeless beyond standard medical care. Concrete suggestions are discussed in the text.

According to the European Typology of Homelessness and housing exclusion (ETHOS), “homeless” persons are those who live in the streets, in public spaces, or in emergency accommodation. Persons who are subject to housing exclusion (houseless persons), however, live in temporary accommodation, for example, transitional supported accommodation (1). According to the German Federal Task Force on Homelessness, about 39 000 homeless persons and about 335 000 houseless persons were living in Germany in 2014—and the trend is rising (2). The transitions between houselessness and homelessness are fluid. The cause for houselessness is an interplay of financial, health related, and social factors (for example, the death of a close relative, separation, experiences of violence, delinquency) (3– 5).

The health of houseless people, especially homeless ones, is often poor. In addition to a multitude of psychiatric and somatic disorders, such persons are exposed to conditions of heat, cold, and damp. A poor diet or insufficient food (6), chronic alcohol misuse, and a lack of personal hygiene lead to and sustain infections and parasite infestations. Houseless people are also exposed to a considerable risk of falling victim to violence. At least 17 violent deaths and 128 cases of bodily harm among houseless people were reported in 2016 (7). Homeless people’s risk of dying prematurely is treble or even quadruple that of the general population. Their mean life expectancy is between 42 and 52 years (8). Postmortem examinations of 207 houseless persons in Hamburg showed that intoxication was the most common cause of death (25%), followed by cardiovascular disorders (17%), infections (primarily pneumonia: 15%), suicide (9%), accidents (7%), and gastrointestinal disorders (6%) (9).

This review article aims to provide an overview of the medical treatment of homeless people in Germany and to answer the following questions:

Which sociodemographic and health related characteristics of homeless people are known?

Which healthcare concepts and services for homeless persons exist in Germany, and which are under discussion internationally?

Methods

To identify scientific publications for this review article, we searched Medline, using the search terms “homeless” AND “health care” OR “healthcare” OR “medical care” in the title. We reviewed 323 hits from 2000–2017, which were almost all available in English or German language versions. Of these we reviewed 119 full-text articles containing data on the sociodemographic characteristics of homeless persons, their health, barriers to accessing standard medical care and the consequences of not accessing healthcare, as well as on concepts of medical care. We identified additional publications on the situation in Germany primarily by reviewing the reports of the German Federal Task Force on Homelessness. We conducted additional online searches regarding services offered by relief organizations in Germany and also searched Google Scholar, using the following search terms in German: “homeless people/homelessness, medical treatment”. Where available, we used primarily analyses of the situation in Germany for this article. All publications available in full text versions were searched for additional references. If publications dealt with similar subjects, we cited in this review article the more recent and—if available—German language studies.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of homeless people

In 2015, the German Federal Task Force on Homelessness published data from 33 256 homeless people from 176 institutions (10). 75% of those documented were men, 20% were up to 24 years old, 13% were 25–29, 23% were 30–39, 22% were 40–49, 16% were 50–59, and 6% were 60 or older. 73% of homeless persons had German citizenship, 12% were EU citizens. Most homeless persons (69%) had a low educational qualification, 18% had an intermediate high school certificate, and 10% had a higher education entrance qualification.

53% lived off public assistance/subsidies, 29% had no income, and 9% were in gainful employment. 75% of homeless people had health insurance at the time of accessing healthcare, 19% did not, and in 7% their insurance status was not clear. Almost half (49%) of all homeless persons had visited a primary care physician before accessing public assistance/subsidies, a higher proportion of women (64%) had done so than men (44%) (10).

Homeless people’s characteristics can vary by location and timing of the data collection. In the three Hamburg practices specializing in providing care for homeless patients, 51% of such patients had German citizenship from June 2013 to May 2014, whereas in the following year it was only 35%. 54% of patients accessing these practices in their first year of operation were members of a health insurance scheme, whereas this was the case for only 27% in the second year (11). The evaluation of mobile medical services for homeless people in North Rhine–Westphalia shows substantial differences between locations: the proportion of persons without insurance cover varied between 10% in Bielefeld and 37% in Münster (12).

The health of homeless people

Many homeless people have mental disorders. Of 232 patients from Munich, who had accessed care in institutions for homeless persons, 75% had a current mental disorder that required treatment. In 74%, a substance induced disorder was found currently or earlier, and 55% of those surveyed had at least one personality disorder (13). Schreiter et al. (e1) provide a detailed analysis of the mental health of homeless persons.

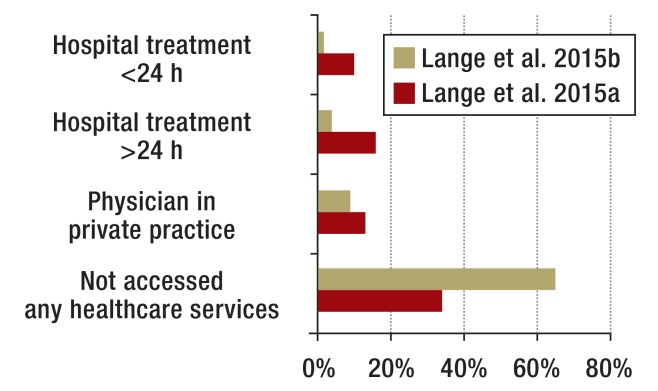

In addition to mental disorders, homeless people are affected by a wide spectrum of symptoms, such as acute and chronic disorders of the respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, and musculoskeletal systems, whose wide range corresponds to the range of conditions treated in general practices, but with a special focus on infectious and parasite diseases, injuries, and skin diseases. Figure 1 shows that the distribution of diagnoses varies by the timing of the data collection as well as its location. In the five analyses of acute treatment diagnoses in primary care practices, mental and behavioral disorders accounted for a proportion of 8–15%. Where data on earlier disorders were collected, further health problems gained prominence. 6% of patients in Berlin reported an earlier neurological disorder, especially epilepsy, 5% reported viral hepatitis, and 1% HIV infection (14%). In North Rhine–Westphalia, 13% of patients had viral hepatitis (12). Systematic health investigations of homeless persons in the context of studies change the range of disorders further: Völlm et al. (as early as in 1996) found dental disorders in 82% of homeless persons, eye disorders in 63% (including vision defects), cardiovascular disorders in 56%, disorders of the musculoskeletal system and the liver in 43% for each, and skin, gastrointestinal, and respiratory disorders in a third each (15).

Standard outpatient care

The most common barrier to homeless persons’ participation in standard outpatient care is their lack of health insurance or the lack of clarity around this. Lange et al. reported this state of affairs in the 1st year of operating a specialized medical practice for homeless persons for 35% of patients; in the 2nd year, the proportion was 46% (11). But even if they are insured, homeless people often do not access standard outpatient care. The reasons are vastly divergent. Lange et al. reported shame (5–8% of patients), fear (4–5%), a lack of trust (6%), long distances (6%), physical or psychological inability (2–10%), financial reasons (5–7%), and language problems (2–9%) (11). Qualitative studies have confirmed the importance of these reasons and have added further aspects: a lack of disease awareness, other priorities (for example, the search for a sleeping place), organizational reasons (for example, unawareness of the location of a medical practice and worry about personal belongings during absence) (16– 21). From the perspective of the healthcare provider, such non-uptake of healthcare services may also be explained by the affected person’s inability to conform to the requirements of standard outpatient care-for example, keeping appointments, being forbidden to consume alcohol or drugs, and being expected to cooperate (11, 22).

Further barriers exist on the healthcare providers’ part. Primary care physicians in Marseille reported homeless patients’ complex needs, which they were not able to meet. They reported that earlier findings were mostly not available, and patients’ medical histories were incomplete. They also reported that homeless patients had been too much of an imposition on their other patients (23). Lester and Bradley found negative attitudes in British primary care physicians towards homeless persons (24). Håkanson und Öhlén concluded from the narratives of homeless persons that physicians need to be aware of the special needs of sick homeless people in order to be able to treat them appropriately (25).

The low uptake of outpatient care entails consequences for people’s health. In Boston, 73% of homeless persons—who were at least in the Health Care for the Homeless program (N = 966)—reported at least one unmet medical need. The most commonly named needs were dental care (41%), fitting spectacles (41%), medications requiring a prescription (36%), medical or surgical care (32%), and psychiatric care (21%) (26). Even in Canada, where all homeless people have insurance cover, the treatment of cardiovascular risk factors, for example, is much poorer than in persons who have homes (27, 28).

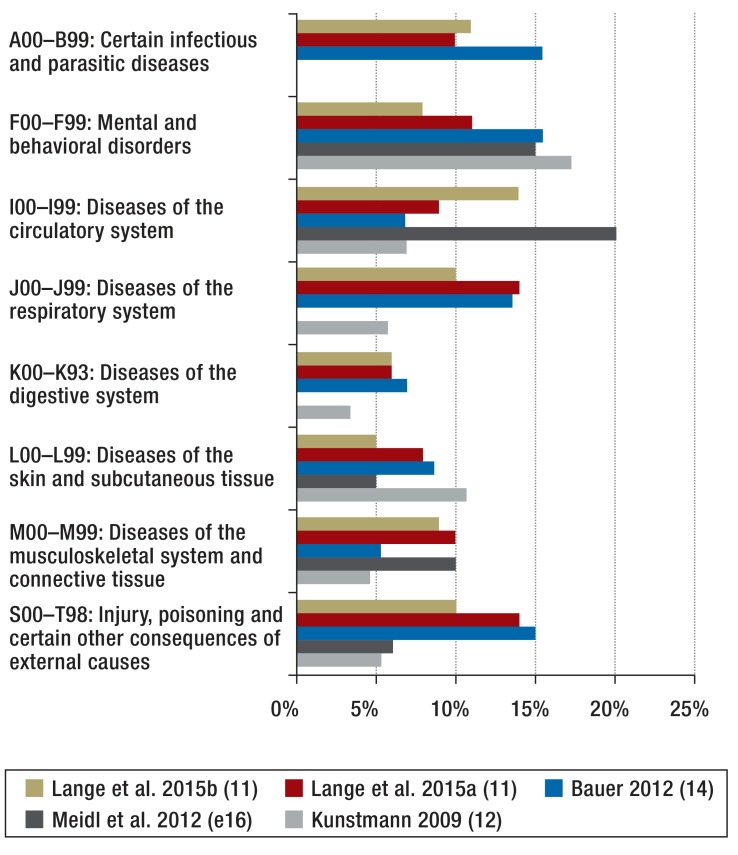

Standard inpatient care

In acute emergencies, homeless people increasingly attend emergency departments in hospitals, because they cannot be refused care in that setting. This is an internationally known phenomenon (29, 30). In the UK, inpatient treatment of a homeless person incurs an average of 8 times the expenditure as inpatient treatment of an 18–64 year old with a home (31). The patients in specialized medical practices for homeless persons in Hamburg reported that in the 6 months before the current consultation, they had been treated in a hospital rather than by a physician in private practice. Most of them had not accessed medical care at all (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Use of standard medical care in the 6 months before attending the specialized practice for homeless people in Hamburg

Lange 2015a = 388 patients in the 1st year of the project;

Lange 2015b = 452 patients in the 2nd year of the project;

The numbers do not add up to 100% in all cases due to missing data.

Concepts of the medical treatment of homeless people

For these reasons, medical treatment of homeless persons is provided mainly within alternative healthcare systems that are funded by government institutions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and on a project-related basis also by health insurers and associations of statutory health insurance physicians. In addition to financial and administrative support for the work of government institutions and NGOs, federal states and municipalities often provide an overview of all regional healthcare services—Hamburg, for example (32).

Foundations and organizations that are dedicated to services for homeless persons are dependent on financial and material donations and volunteer staff. Table 1 shows an overview of the larger organizations and the range of their medical services.

Table. Overview of larger organizations that provide medical services for homeless people*.

| Organization/foundation | Medical services | Coverage | Sources |

| German Caritas Association | Outpatient practices, mobile medical and dental practices, health advice, if needed specialist referral; in Hamburg also 18-bed intermediate center for homeless people, 4 of these beds for tuberculosis patients; in Berlin also traditional Chinese medicine | Nationwide, large cities | (e16– e21) |

| Malteser Germany | Transitional institutions for homeless persons, for example for men with addiction problems in Hamburg; “Malteser Migrant Medicine” especially for people without health insurance, also accessed by people with German citizenship, GP/internal medical consultations, depending on the region also consulta‧tions with specialists, collaborations with hospitals, pharmacies, etc. |

“Malteser Migrant Medicine” in 18 locations | (e22– e25) |

| Johanniter Germany | Bus providing homeless people with hot drinks, sleeping bags, clothes in cold weather conditions | Bremen | (e26) |

| Diakonie (social welfare organization of Germany’s Protestant churches) | Medical consultations, wound experts, help with addiction disorders, in Düsseldorf e.g. provision of spectacles | Nationwide, large cities | (e27– e30) |

| Bahnhofsmission (aid organization located at more than a hundred railway stations) | Medical consultations and primary care in some places, e.g. Husum | Nationwide in 105 railway stations, medical treatment only in some locations | (e31) |

| German Red Cross | Recovery rooms for homeless people who are too sick to recuperate in the streets | Nationwide, different services | (e32, e33) |

| Jenny De la Torre Foundation | Health center: GP practice especially tailored for homeless patients, additionally psychological and specialist medical consultations (ophthalmologist, internist, orthopedic specialist, dermatologist, dentist) | Berlin | (e34) |

| Katholischer Männerfürsorgeverein Munich e. V. (Catholic organization for homeless men’s welfare) | Long-term institutions offering medical and nursing support | Munich and environs | (e35) |

* This overview contains examples; we don’t claim completeness, as regional services are constantly changing and are not documented systematically

Discussion

The medical treatment of homeless people takes into account the fact that homeless persons do not or cannot access basic standard outpatient care. Services outside the standard system are often provided as outreach services—for example, by mobile medical and dental practices—and are funded from government and non-government sources. The desire to treat homeless people within the standard healthcare system seems unrealistic when considering the manifold barriers on the part of homeless persons and regular outpatient services. When evaluating mobile medical services for homeless people in North Rhine–Westphalia, it was also pointed out that the evaluated projects did not create parallel healthcare services, since 90% of patients “had been uncoupled from any outpatient medical treatment” (12). There is wide agreement that reliable outpatient treatment is important, among other reasons in order to prevent unnecessary inpatient stays and expenditure (33, 34).

The medical treatment of homeless people focuses on acute treatment events, prevention plays a minor role. Longer-term treatment of chronic conditions runs into difficulty, as, even if health insurance is a possibility, many homeless persons cannot cope with the administrative demands of maintaining insurance cover and the financial expense of paying for prescriptions (5, 35). Funding long-term medication from donations, however, comes up against the financial restrictions of the relevant institutions (11).

Another characteristic of medical services for homeless persons is its specialization on this target group and its embedding in an overall concept of social services (provision of places to eat, sleep, and wash, clean clothing, advice). There is international consensus that this combination is necessary (for example, 29, 36), from the perspective of homeless people too (37– 39). Such multiple service offerings cannot be provided within the context of standard medical services, and medical needs are in some ways different to the requirements of non-homeless patients. Extensive wound care or infestation with parasites are just two examples in this context. Social workers have an important role in enabling homeless persons to access medical, and especially psychiatric, care (11, e2).

The (acute) medical treatment of homeless people targets primarily somatic disorders. Psychiatric problems are not treated by default in primary care physicians’ consultations (11, 14). This approach is understandable, as homeless people often seek medical help only in case of acute (somatic) crises (17). They often lack motivation to seek treatment for their psychiatric problems (e3). On the other hand, the integration of easy-access psychiatric expertise into the concept of outpatient medical care is being called for at an international level (e4– e8). In a Canadian study, 73 homeless persons received concomitant psychiatric treatment at their institution for homeless patients. After 6 months, overall health had improved in 35%, and 49% of those patients had found accommodation (e9). Outpatient psychiatric services are also required for continued psychiatric care provision after hospital discharge (e10).

“Housing first” is the name given to approaches to provide homeless people with accommodation before anything else, and to then tackle their somatic-psychiatric problems second. A study from the US showed for 95 chronically homeless people with severe alcohol problems a 53% reduction in the overall cost (medical expenditures plus the costs for specialized institutions) compared with a control group (e11). Another study showed that by applying “housing first,” healthcare costs for the first year fell by 45%—with participants reporting improved medical treatment (e12).

In cities such as Hamburg and Hanover, homeless people who are too sick to remain in the streets but cannot or refuse to be treated in hospital can access intensive medical treatment and care in intermediate care centers (Krankenstuben). In these, the socio-pedagogical aspect of care is more intensive and treatment more flexible. The evaluation of one such institution in Hanover showed positive effects for participants’ health and their subsequent housing situation (e13). De Maio et al. evaluated such an intermediate care center in Milan (e14).

The diversity of medical services for homeless people is based on organically grown structures and local estimates of need. However, one suspects that homeless people receive better care in some cities than in others. The Mainz model is one example for diversified services for homeless people; this model also includes services for severely ill homeless people (5). For this reason, setting a guaranteed minimal standard would be desirable, which the state would ensure.

Initiatives for the medical treatment of persons without official documents have a special role (e15). In this setting, NGO initiatives have a crucial role in Germany because the German state does not see this as an area of activity to be involved in. Similarly, free medical treatment is increasingly accessed by people who are poor but not homeless (e16). Financial alternatives will need to be developed in order to support poor people in staying in the standard healthcare system.

In contrast to Canada, the US, and the UK, very few studies in Germany have investigated the medical treatment of homeless people. Research is needed into the description of currently provided healthcare services and into the effects of new projects. Furthermore, little is known, even internationally, on emergency and inpatient treatment of homeless persons—for example, about reasons for hospital admission, services rendered, problems in providing services, and the whereabouts of the homeless patients. Fundamentally, studies are needed that investigate how homeless people’s own initiative in accessing services as well as their ability to cooperate might be improved.

Conclusion

The medical treatment of homeless people is integrated in a complex network of social services. To improve the health of homeless persons, it seems necessary to extend those services in the following areas:

Increasing state funding, in order to guarantee a (to be defined) minimum standard of medical treatment/care and to be able to focus on chronic disorders and prevention too.

Improving the range of services, with easy access to specialists, especially psychiatrists and psychotherapists, and to dentists.

Providing more intermediate care centers (Krankenstuben) for homeless people.

Increasing the general population’s willingness/readiness to make donations, by providing more information in the media.

Figure 1.

Acute diagnoses according to ICD-10 in patients in German data collections, who had received treatment in specialized practices for homeless people

% relate to:

Hamburg, Lange 2015b = 451 diagnoses (in 452 patients in the 2nd year of the project)

Hamburg, Lange 2015a = 553 diagnoses (in 388 patients in the 1st year of the project)

Berlin, Bauer = 543 treatment diagnoses (in 440 patients)

Hanover, Meidl = 2700 primary treatment events (in as many consultations in 2010),

Northe Rhine–Westphalia, Kunstmann = 31 363 diagnoses (in 23 231 patients)

Key Messages.

Physicians can contribute to improving the medical care of homeless people by

Dealing with homeless people in a respectful manner and conducting a careful medical examination according to valid standards .

Becoming familiar with the circumstances in which homeless people live and check the options for adequate treatment in the homeless setting (for example, long-term medication for impoverished people or wound care during homelessness).

Finding out in collaboration with the homeless patient whether it is possible to link up with a social service institution, so as to improve the continuity of care

In view of very high psychiatric comorbidity, motivating patients to seek psychiatric co-treatment and referring them to appropriate services.

Becoming involved in specific medical care projects for homeless persons (see organizations listed in the Table).

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.ETHOS - Europäische Typologie für Obdachlosigkeit. Wohnungslosigkeit und prekäre Wohnversorgung. www.bawo.at/fileadmin/user_upload/public/Dokumente/Publikationen/Grundlagen/Ethos_NEU_d.pdf (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe e. V. Zahl der Wohnungslosen. www.bagw.de/de/themen/zahl_der_wohnungslosen/index.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke C, Johnson EE, Bourgault C, Borgia M, O’Toole TP. Losing work: regional unemployment and its effect on homeless demographic characteristics, needs, and health care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:1391–1402. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Paulgerg-Muschiol L. Wege in die Wohnungslosigkeit - Eine qualitative Untersuchung. Dissertation, Universität Siegen, www.d-nb.info/101316878x/34 (last accessed on 19 June 2017) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trabert G. Medizinische Versorgung für wohnungslose Menschen- individuelles Recht und soziale Pflicht statt Exklusion. Gesundheitswesen. 2016;78:107–112. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-111011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langnäse K, Müller MJ. Nutrition and health in an adult urban homeless population in Germany. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:805–811. doi: 10.1079/phn2000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.BAG Wohnungslosenhilfe. Zahlen zur Gewalt gegen wohnungslose Menschen. www.bagw.de/de/themen/gewalt/statistik_gewalt.html (last accessed on 9 August 2017) 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connell JJ. Premature mortality in homeless populations: a review of the literature Nashville: National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc., www.santabarbarastreetmedicine.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/PrematureMortalityFinal.pdf (last accessed on 9 August 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grabs J. Todesursachen von Wohnungslosen in Hamburg Eine Analyse von 307 Todesfällen. Dissertation, Universität Hamburg, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe e. V. (BAG W) Jahresbericht 2015. www.bagw.de/de/themen/statistik_und_dokumentation/statistikberichte/index.html (last accessed on 9 August 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange C, Boczor S, Rakebrandt A, Posselt T, Scherer M, Kaduszkiewicz H. Evaluation der Schwerpunktpraxen für Wohnungslose in Hamburg Bericht auf Anfrage bei Hanna Kaduszkiewicz erhältlich. Abschlussbericht, Hamburg, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunstmann W. Medizinische Versorgung wohnungsloser Menschen in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Evaluation des Umsetzungskonzeptes Abschlussbericht, Münster, www.mgepa.nrw.de/mediapool/pdf/gesundheit/Evaluationsbericht.pdf (last accessed on 9 August 2017) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahn T, Brönner M. Seelische Erkrankungsrate in den Einrichtungen der Wohnungslosenhilfe im Großraum München (SEEWOLF)-Studie - eine Zusammenfassung, München, 2014. www.idw-online.de/de/attachmentdata37253.pdf (last accessed on 9 August 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer TE. Medizinische und soziodemographische Charakteristika der Patienten des Berliner Gesundheitszentrums für Obdachlose. Dissertation, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Völlm B, Becker H, Kunstmann W. Prävalenz körperlicher Erkrankungen, Gesundheitsverhalten und Nutzung des Gesundheitssystems bei alleinstehenden wohnungslosen Männern: eine Querschnittsuntersuchung. Soz Praventivmed. 2004;49:42–50. doi: 10.1007/s00038-003-3064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen CK, Hudak PL, Hwang SW. Homeless people’s perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. JGIM. 2007;22:1011–1017. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins DC. Experiences of homeless people in the health care delivery system: a descriptive phenomenological study. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25:420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nickasch B, Marnocha SK. Healthcare experiences of the homeless. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rae BE, Rees S. The perceptions of homeless people regarding their healthcare needs and experiences of receiving health care. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:2096–2107. doi: 10.1111/jan.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corrigan P, Pickett S, Kraus D, Burks R, Schmidt A. Community-based participatory research examining the health care needs of African Americans who are homeless with mental illness. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26:119–133. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martens WH. Vulnerable categories of homeless patients in Western societies: experience serious barriers to health care access. Med Law. 2009;28:221–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiger I. Die Auswirkungen von Wohnungslosigkeit auf die Gesundheit und den Zugang in das Gesundheitssystem. Dissertation, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jego M, Grassineau D, Balique H, et al. Improving access and continuity of care for homeless people: how could general practitioners effectively contribute? Results from a mixed study. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013610. e013610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lester H, Bradley CP. Barriers to primary healthcare for the homeless: the general practitioner’s perspective. Eur J Gen Pract. 2001;7:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Håkanson C, Öhlén J. Illness narratives of people who are homeless. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2016;11 doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.32924. 32924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baggett TP, O’Connell JJ, Singer DE, Rigotti NA. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1326–1333. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee TC, Hanlon JG, Ben-David J, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in homeless adults. Circulation. 2005;111:2629–2635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khandor E, Mason K, Chambers C, Rossiter K, Cowan L, Hwang SW. Access to primary health care among homeless adults in Toronto, Canada: results from the Street Health survey. Open Med. 2011;5:e94–e103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285:200–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang SW, Chambers C, Chiu S. A comprehensive assessment of health care utilization among homeless adults under a system of universal health insurance. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):S294–S301. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Office of the Chief Analyst, Department of Health. www.housinglin.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Housing/Support_materials/Other_reports_and_guidance/Healthcare_for_single_homeless_people.pdf (last accessed on 9 August 2017) London: 2010. Healthcare for single homeless people. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamburg, Behörde für Arbeit, Soziales, Familie und Integration. Das soziale Hilfesystem für wohnungslose Menschen 2015/2016. www.hamburg.de/contentblob/127994/eb7be91ae2f6671e611c0d391eb5a553/data/hilfesystem-datei.pdf (last accessed on 19 June 2017) 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang SW, Henderson MJ. Health care utilization in homeless people: translating research into policy and practice Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Working Paper No. 10002, www.meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/workingpapers/wp_10002.pdf (last accessed on 9 August 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han B, Wells BL. Inappropriate emergency department visits and use of the Health Care for the Homeless Program services by homeless adults in the northeastern United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:530–537. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heidenheimer Zeitung. Wenn Wohnungslose Medikamente brauchen. www.swp.de/heidenheim/lokales/heidenheim/wenn-wohnungslose-medikamente-brauchen-11903840.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bharel M, Lin WC, Zhang J, O’Connell E, Taube R, Clark RE. Health care utilization patterns of homeless individuals in Boston: preparing for medicaid expansion under the affordable care act. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S311–S317. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daiski I. Perspectives of homeless people on their health and health needs priorities. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:273–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hewett NC. How to provide for the primary health care needs of homeless people: what do homeless people in Leicester think? Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irestig R, Burström K, Wessel M, Lynöe N. How are homeless people treated in the healthcare system and other societal institutions? Study of their experiences and trust. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:225–231. doi: 10.1177/1403494809357102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Schreiter S, Bermpohl F, Krausz M, et al. The prevalence of mental illness in homeless people in Germany—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:665–672. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Verlinde E, Verdée T, Van de Walle M, Art B, De Maeseneer J, Willems S. Unique health care utilization patterns in a homeless population in Ghent. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Bonin JP, Fournier L, Blais R, Perreault M, White ND. Health and mental health care utilization by clients of resources for homeless persons in Quebec city and Montreal, Canada: a 5-year follow-up study. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2010;37:95–110. doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Zur J, Jones E. Unmet need among homeless and non-homeless patients served at health care for the homeless programs. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:2053–2068. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Palepu A, Gadermann A, Hubley AM, et al. Substance use and access to health care and addiction treatment among homeless and vulnerably housed persons in three Canadian cities. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075133. e75133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Weber M, Thompson L, Schmiege SJ, Peifer K, Farrell E. Perception of access to health care by homeless individuals seeking services at a day shelter. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Salize HJ, Horst A, Dillmann-Lange C, et al. Needs for mental health care and service provision in single homeless people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s001270170065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Längle G, Egerter B, Petrasch M, Albrecht-Dürr F. Versorgung obdachloser und wohnungsloser psychisch kranker Männer in der Kommune - eine kontrollierte Interventionsstudie. Psychiat Prax. 2006;33:218–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-834688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Stergiopoulos V, Dewa CS, Rouleau K, Yoder S, Chau N. Collaborative mental health care for the homeless: the role of psychiatry in positive housing and mental health outcomes. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:61–67. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Burra TA, Hwang SW, Rourke SB, et al. Homeless and housed inpatients with schizophrenia: disparities in service access upon discharge from hospital. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2012;10:778–789. [Google Scholar]

- E11.Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301:1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Wright BJ, Vartanian KB, Li HF, Royal N, Matson JK. Formerly homeless people had lower overall health care expenditures after moving into supportive housing. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:20–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Doering TJ, Hermes E, Konitzer M, Fischer GC, Steuernagel B. Health situation of homeless in a health care home in Hannover. [Article in German] Gesundheitswesen. 2002;64:375–382. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.De Maio G, Van den Bergh R, Garelli S, et al. Reaching out to the forgotten: providing access to medical care for the homeless in Italy. Int Health. 2014;6:93–98. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Klug DM. Krankheitserfahrungen von nicht-dokumentierten Migranten: eine qualitative Studie. Dissertation, Universität Hamburg, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- E16.Meidl J, Wenzlaff P, Sens B, Goesmann C. Requirements for the provision of healthcare to socially disadvantaged population groups: evaluation of 10 years of medical care provided to the homeless in Hanover [article in German] Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2012;106:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Caritas-Ratgeber. Überlebenshilfen für Wohnungslose. www.caritas.de/hilfeundberatung/ratgeber/wohnungslosigkeit/lebenaufderstrasse/ueberlebenshilfen-fuer-wohnungslose (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E18.Caritasverband für das Erzbistum Berlin e. V. Ambulante Wohnungslosenhilfe. www.caritas-berlin.de/beratungundhilfe/berlin/wohnungsnot/ambulante-wohnungslosenhilfe (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E19.Caritas. Krankenmobil. www.caritas-hamburg.de/hilfe-und-beratung/arme-und-obdachlose/krankenmobil/krankenmobil (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E20.Caritas. Krankenstube für Obdachlose. www.caritas-hamburg.de/hilfe-und-beratung/arme-und-obdachlose/krankenstube-fuer-obdachlose/ (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E21.Caritas Hannover. Medizinische Hilfe für alle. www.caritas-hannover.de/hilfe-und-beratung/wohnungslos/strassenambulanz/strassenambulanz (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E22.Caritas Berlin. Traditionelle Chinesische Medizin. www.caritas-berlin.de/beitraege/traditionelle-chinesische-medizin/426588/ (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E23.Malteser in Hamburg. Suchtkrankenhilfe für Wohnungslose. www.malteser-hamburg.de/dienste-und-leistungen/weitere-dienstleistungen/suchtkrankenhilfe-fuer-wohnungslose.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E24.Malteser. Malteser Migranten Medizin vor Ort. www.malteser.de/menschen-ohne-krankenversicherung.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E25.Malteser Migranten Medizin. www.caritas-nrw.de/themendossiers/krankenhaeuser/malteser-migranten-medizin (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E26.Malteser-Bilanz: 9500 Patienten ohne Krankenschein behandelt. www.berlin.de/aktuelles/berlin/3798769-958092-malteserbilanz-9500-patienten-ohne-krank.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E27.Die Johanniter. Johanniter unterstützen Obdachlose in Bremen. www.johanniter.de/die-johanniter/johanniter-unfall-hilfe/juh-vor-ort/landesverband-niedersachsenbremen/verbaende-vor-ort/bremen-verden/aktuelles/nachrichten/johanniter-unterstuetzen-obdachlose-in-bremen/ (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E28.Diakoniewerk Essen. Suchtberatung. www.diakoniewerk-essen.de/de/Wohnungslose%20und%20Gef%C3%A4hrdete/Suchtberatung/6.58 (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E29.Diakoniewerk Essen. ZusammenLeben gestalten. www.diakoniewerk-essen.de/de/Wohnungslose%20und%20Gef%C3%A4hrdete/Wohnungslosenberatung/6.56 (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E30.Diakonie in Dortmund und Lünen. Existenzielle medizinische Grundversorgung. www.diakoniedortmund.de/wohnungslos/zentrale-beratungsstelle-fuer-wohnungslose-menschen-zbs/aufsuchende-medizinische-hilfen.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E31.Evangelischer Pressedienst, Landesdienst West. Diakonie Düsseldorf verbessert medizinische Betreuung für Obdachlose. www.bahnhofsmission.de/index.php?id=99&woher=&bm=33 (last accessed on 11 September 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E32.Diakonisches Werk Husum. Medizinische Notfallhilfe in der Bahnhofmission. www.dw-husum.de/de/einrichtungen/medizinische-notfallhilfe-in-der-bahnhofmission.php (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E33.Deutsches Rotes Kreuz. Hilfe für Wohnungslose. www.drk.de/hilfe-in-deutschland/existenzsichernde-hilfe/wohnungslosigkeit/ (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E34.Deutsches Rotes Kreuz, Kreisverband Ulm e. V. Wohnungslosigkeit. drk-ulm.de/angebote/soziale-dienste/wohnungslosenhilfe.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E35.Jenny de la Torre Stiftung. Das Gesundheitszentrum. www.delatorre-stiftung.de/gesundheitszentrum.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E36.Katholischer Männerfürsorgeverein München e. V. Wohnungslosenhilfe. www.kmfv.de/hilfe-und-beratung/wohnungslos/index.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017) [Google Scholar]