Abstract

Aims

To identify rehabilitation providers’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators of patient engagement in hip fracture patients in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) within the social ecological model.

Methods

We conducted 13 focus groups in SNFs throughout Los Angeles County comprised of rehabilitation staff (n=99). Focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. A secondary analysis of themes related to patient engagement were identified and organized within the social ecological model.

Results

Clinicians identified barriers and facilitators of patient engagement across all levels of the social ecological model: public policy (e.g., insurance), organizational (e.g., facility culture), interpersonal (e.g., clinicians fostering self-reflection), and intrapersonal (e.g., patients’ anxiety).

Conclusions

Examining barriers and facilitators to patient engagement has highlighted areas which need to be sustained and improved. Thus, these findings future efforts to enhance patient engagement in order can to optimize patient healthcare decisions.

Keywords: Post-acute care, rehabilitation, patient engagement, skilled nursing facility

Approximately 40% of Medicare beneficiaries use post-acute care each year, which is predicted to rise as the US population continues to age (Gage et al., 2011; Mechanic 2014). Despite this increase in utilization, there has been little improvement in the quality of care as indicated by poor patient outcomes, such as hospital readmission, mortality, and little change in functional status (MEDPAC 2015). This trend in high utilization and suboptimal outcomes in post-acute care is consistent with the broader healthcare system. Thus, to incentivize the delivery of high quality care in post-acute care, the US healthcare system is transitioning from a fee-for service model to a health system based on value (“Improving Medicare Post Acute Care Transformation Act” 2014; “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” 2010).

By aligning payment to quality of care and outcomes, not the volume of services, the goal is to incentivize the delivery of high quality patient-centered care (“Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” 2010). Patient-centered care, which encompasses shared decision making and engaging patients, is referenced throughout The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in multiple mandates (Frosch et al., 2014; Millenson et al., 2012). Similarly, patient engagement, which is a collaboration in healthcare decision making between patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers, is a priority of the ACA to improve care quality and patient outcomes (Epstein et al., 2010; Hibbard et al, 2013).

Patients experiencing a hip fracture are one example of a post-acute care rehabilitation population that has poor patient outcomes, including high rates of mortality, morbidity, institutionalization, subsequent injuries, and reduced quality of life (Marks 2010; Parker et al., 2006). After the initial hospitalization, 90% of Medicare patients with a hip fracture are discharged to post-acute care, with the majority being admitted to a skilled nursing facility (SNFs) (Freburger et al., 2012; Nguyen-Oghalai et al., 2008). For the majority of these patients the goal of post-acute care rehabilitation is to return to the community (Stucki et al., 2005). Research has shown comprehensive care can enhance functional recovery (Beaupre et al., 2013). However, poor transitions from post-acute care to the community are common and can lead to hospital readmissions and poor health outcomes (Leland et al., 2015; Mechanic 2014). More specifically, only 57% of patients experiencing a hip fracture were able to return home and stay home at least 30 days, while an additional 14% returned to the community, but did not reach the 30-day window of remaining in the community (Leland et al., 2015). Towards this end, patients have prioritized the importance of going home and staying home as a meaningful rehabilitation outcome (Mackenzie et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2010). Thus, as comprehensive patient-centered care has been able to improve functional recovery, it is a vital approach to utilize in addressing other rehabilitation outcomes, such successful community discharge where patients remain in the community.

Efforts to enhance patient outcomes necessitate the delivery of efficient, high quality patient-centered care, which includes care coordination between organizations as well as among patients, caregivers, and members of the interdisciplinary post-acute care team (Ackerly et al., 2014; Rosenbaum 2011). Within post-acute care rehabilitation, improving patient engagement allows for the patient to actively participate in their therapy and make informed healthcare decisions. When patients are able to make informed decisions about their own healthcare, it influences their self-management behaviors, health services use and costs, healthcare experience, and health outcomes (Hibbard et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2009). To this end, patient engagement is multifaceted and can be influenced by a variety of factors, which can be addressed within the social ecological model.

Theoretical Model

The social ecological model provides a framework to examine the factors that influence an individual’s behavior from a system perspective, which includes the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem (Bronfenbrenner 1977). McLeroy and colleagues (1988) modified Brofenbrenner’s ecological model to examine behavior related to health. Their model is adjusted to include intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy levels. The intrapersonal factors aim to capture the individual’s characteristics, including one’s own knowledge and psychological characteristics. The interpersonal factors describe the relationships between individuals and how these relationships influence one’s health behavior. Institutional factors include the formal and informal rules and regulations that are established within an organization that influence the behavior. The community factors capture the impact that relationships among organizations and geographic locations can have on health behavior. Finally, public policy characteristics are laws and policies established at the local, state, and national level.

By viewing patient engagement in post-acute care within the social ecological model, multiple levels of influence can be viewed as impacting patient engagement. For example, in order, to increase patient engagement in healthcare settings (e.g., geriatric care units) interventions have been designed at the individual level (i.e., with patients, family, and providers) and at the organizational level (Wolff et al., 2009). This framework provides the structure to examine barriers and facilitators to patient engagement throughout the multiple systems that impact the patient’s behaviors. Currently, there is limited evidence documenting best practice for facilitating patient engagement within post-acute care. Given the common utilization of post-acute care service among patients with a hip fracture, this population can provide insight into patient engagement and the importance of collaboration between clinicians and patients. In order to improve patient engagement in post-acute care, there is a need to understand factors impacting engagement. The objective of this study was to identify factors that support or hinder patient engagement from the perspective of the post-acute care providers.

Methods

Research Design

A secondary analysis of data collected from a larger funded study was conducted (Leland et al., 2017). The original study used focus groups to allow post-acute care providers to share their experiences and perspectives on delivering high quality hip fracture rehabilitation. The study sample was drawn from SNFs throughout Los Angeles County and participants included occupational therapists, physical therapists, occupational therapy assistants, and physical therapy assistants. The study was approved by University of Southern California’s Institutional Review Board.

Study Population and Data Collection

Purposive sampling of facilities was done to capture a diverse group of SNFs that varied in key characteristics known to impact care delivery, such as location, resources, staffing, and patient-case mix (Castle 2008; Gozalo et al., 2015). The sample of SNFs were obtained from the Medicare Nursing Home Compare website, which is a government-run site that provides information on organizational characteristics and quality of care measures for nursing facilities that receive Medicare and Medicaid payments. Eligible facilities in Los Angeles County were identified and contacted for participation in the study. The facilities’ administrative staff assisted in disseminating information on the study and focus groups to the staff.

Participants were eligible to be included in the study if they were rehabilitation providers (1) with at least one year of clinical experience working with hip fracture patients; (2) employed at the facility; (3) communicated in English; (4) were present on the day the focus group was conducted; and (5) had given informed consent.

One focus group was held in each of the 13 facilities and were semi-structured lasting between 30 minutes to 75 minutes in length. One researcher with training in qualitative methods facilitated the focus groups and one research assistant attended the focus groups to document field notes. An interview guide was utilized to explore the participants’ perspectives and experiences on providing high quality care for hip fracture rehabilitation.

Ninety-nine clinicians participated in the focus groups. Fifty percent of the clinicians were occupational therapy practitioners. Participants included 30 men and 69 female ranging in age from 22 to 64 years (mean [M] = 41.44, standard deviation [SD] = 9.16). In addition, 42% of participants were Asian, 2% African American/Black, 41.4% White, and 8.1% other (i.e., participants who selected other or more than one race). On average, clinicians had been working for 2.92 years (SD = 3.16) in the facility where the focus groups were conducted. However, clinicians had an average of 7.18 years (SD = 6.24) of experience working in a SNF.

Data Analysis

Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three members of the research team read the transcripts to ensure that the audio recordings were replicated in the transcripts. An approach rooted in grounded theory was utilized by the research team to systematically analyze the transcripts for major themes and sub-themes in the original study (Corbin et al., 1990; Padgett 2012). The grounded theory approach for the initial study used three steps of coding (i.e., open, axial, and selective) and has been detailed in the original study’s manuscript (Leland et al., 2017). Patient engagement arose as a major theme in the initial analysis. Thus, data were further analyzed to identify sub-themes of patient engagement by re-coding data categorized as patient engagement. The social ecological model was used as a framework to organize the sub-themes that arose from the data, distinguishing between barriers and facilitators of patient engagement and identifying strategies to overcome those barriers. Themes were categorized into the different levels of the model. The qualitative data analysis software package Atlas.ti (Version 7.5.6) was used to assist with organizing the data and facilitating data analysis.

Results

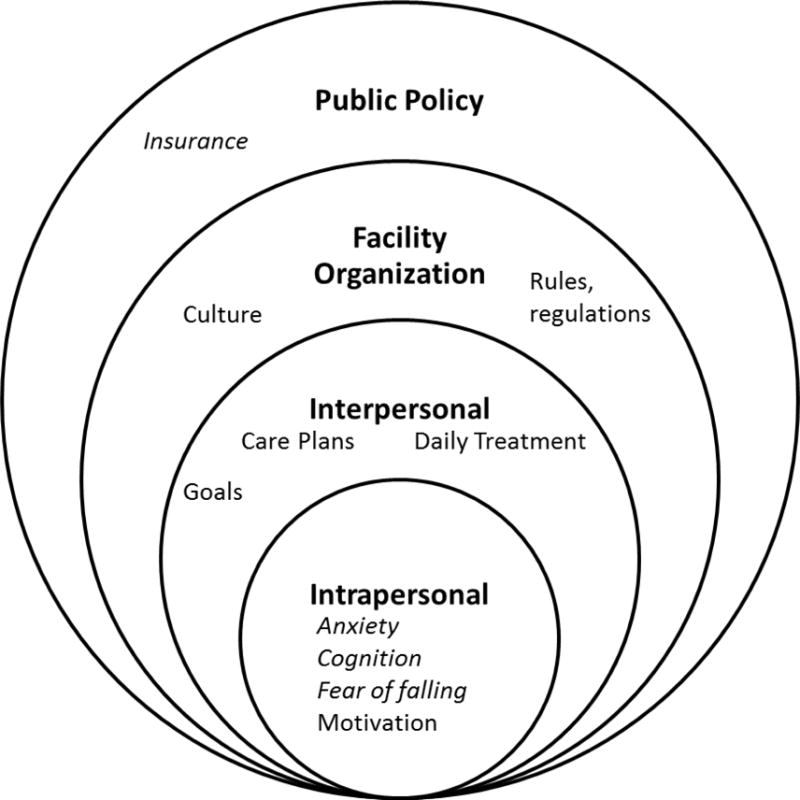

Qualitative data analysis of the focus group transcripts identified clinicians’ perspectives of barriers and facilitators to patient engagement across all levels of the ecological model: intrapersonal level, interpersonal level, organization level, and at a public policy level (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Common themes found within the social ecological model that are barriers (italicized) and facilitators (not italicized).

Intrapersonal

Four themes were consistently described that captured the characteristics of patients that affect their involvement in their own healthcare decisions, three of which were barriers: (1) anxiety, (2) cognitive status, and (3) fear of falling were described as potential barriers. Patient motivation was identified as a facilitator to patient engagement.

Anxiety

Participants frequently described the anxiety that patients have when transitioning from the acute care hospital into a SNF as a barrier to patient engagement. Specifically, clinicians described a lack of knowledge about the transition processes that often caused anxiety and unease for patients who enter into a new environment, which impacts a patient’s ability to participate in their healthcare. A participant described, when you first meet them, there’s a lot of anxiety for them [the patient], because the patient suffered a hip fracture and after a surgical repair, they are transitioning to a new environment. The quick transition to, not only different healthcare settings, but also transitions between different healthcare providers results in patients not having necessary information that they need to make informed decisions, causing them to be anxious about their stay. One clinician described the first impression that many patients have when entering the SNF,

I think transitioning from the hospital, [to the SNF] and knowing ‘What am I supposed to be here for?’ At the same time, ‘when do I get to go home? I want to go now. When’s my next appointment?’ So all those things go in the very first day they come in. And different departments coming in and they [the patients] see what their basic skilled nursing facility is. They feel like they’re in an elderly facility, so they feel like ‘Am I supposed to be here? Am I in the right place?’

Participants frequently described the scenario in which patients are not prepared for the SNF care transition during acute hospital stay. As a result, they may have a limited understanding of the care transition process and the focus of care in this subsequent healthcare setting, facilitating patient anxiety and uncertainty. Thus, as one clinician stated, orientating them [the patient] to this [the SNF] as a new household for a while, this is a new setting, is an important clinical strategy to help patients settle into their new environment and situate the individual to engage in their care decisions moving forward.

Cognitive status

Similarly, clinicians commonly described patients’ cognitive status as a common characteristic that limited patient engagement. For patients who have dementia or cognitive impairment, they don’t really understand why we’re doing what we’re doing. It can be difficult for patients with dementia to participate in their treatment since they’re apt to either isolate or just withdraw from an activity because it’s hard to process what’s really going on. In these cases, clinicians emphasized the importance of engaging family members or caregivers to identify strategies for engagement and ensure care delivery addressed the goals of the patient and family.

Fear of falling

The third theme focused on fear of falling. Consistently across focus groups, clinicians described the frequency in which this fear affected a patient’s ability to participate in their treatment plan. Fear of falling is prevalent among individuals whom have fallen and experienced a hip fracture, resulting in an elevated concern for subsequent falls and injuries (Boyd et al., 2009; Visschedijk et al., 2010). As one clinician described this fear:

They’re fractured and then fell…So, because of that, they come in here, even though they’ve been surgically repaired and everything is good [medically stable]now, they’re very afraid. They don’t want to walk, they don’t want to get up by themselves, they don’t want to do anything because they’re, like, ‘no, no, no, I don’t want to fall.

This fear of falling can hinder the patient’s ability to participate in their therapy sessions, which in turn limits functional progress and achievement of patient’s goals. Thus, it was important for clinicians to address fear of falling because of the debilitating impact fear of calling can have on a patient, one clinician stated, one of the biggest things I want to eliminate in the patient is the fear.

Motivation

The final theme focusing on intrapersonal characteristics was motivation. When patients are motivated to actively engage in their therapy sessions, it facilitates their recovery and contributes to better health outcomes. One clinician noted, If they’re [the patients] really motivated, they’re working real hard [during therapy sessions]. Some [patients] say, ‘I will work with you, I will be okay.’ Motivated patients participate in therapy, collaborate with their clinicians to develop their care plans, complete therapy activities, and actively learn the strategies they are taught.

Intrapersonal themes to engagement

The intrapersonal characteristics of an individual can greatly impact whether or not a patient engages in their therapy sessions and their overall rehabilitation process. These characteristics, such as anxiety, cognitive status, and fear of falling, can be a hindrance to patient engagement in therapy, whereas motivation can support engagement.

Interpersonal

The interpersonal relationship between the patient and the clinician greatly influenced a patient’s opportunity to engage in their treatment. Three themes emerged regarding the interpersonal relationship: (1) care plan, (2) daily treatment sessions, and (3) fostering self-reflection.

Care plan

Clinicians frequently described engagement in the context of communication with patients and their caregivers, particularly with respect to developing a patient-centered treatment plan. By involving the patient and caregivers in the development of the care plan, patients and caregivers are able to collaborate on goal setting and treatment prioritization. As one clinician explained, it is more asking the patient and family members what do they feel [are important treatments and therapy goals], and what is their confidence [level]? What do they need? And then we try to address that. Through ongoing dialogue, clinicians are able to identify patients’ preferences guide their own care planning. By collaborating with the patient, clinicians can establish goals that reflect the patient’s priorities and work together to achieve them. As one clinician noted,

I think that’s something to think about, we all have our goals as therapists, you know…I want them [the patients] to do this, or I want them to do that, but also keeping in mind that our patients are going to have their own set of goals, and that’s always something that you have to ask.

Daily treatment sessions

Similarly, daily treatment sessions, the second interpersonal patient engagement theme, was commonly discussed among the clinicians as an important area to engage the patient, specifically when scheduling the session. For example, one clinician described the process of scheduling daily therapy session with each patient. In his facility, there are no set appointments for the patients, I go around in the morning, make the rounds, see what time [the patient wants to have their therapy]. - you know, depending on their appointments, shower time, everything else that they have going on that day. This allows the patient to have a voice in scheduling their own treatment plan instead of having others determine therapy time for them. By working with the patient, clinicians are able to motivate the patient to work towards a goal that is meaningful and applicable for them to achieve.

Fostering self-reflection

Finally, the clinicians discussed the importance of fostering patients’ self-reflection and recognition of their own progress. By facilitating a patient’s insight into their progress, the patient is able to recognize that they are improving. Furthermore, when patients are able to identify their own improvement, this process of self-awareness, can motivate the patients to continue to participate in therapy sessions and actively engage in their rehabilitation plan of care. A clinician mentioned the use of therapeutic use of self to initiate the process of self-awareness:

I think it helps to ask the patient open-ended questions at the end [of a session]. ‘How did you do today? Can you see a difference compared to day one?’ So really, it’s coming from them. It’s, again, self-reflection. A lot of therapeutic use of self; us being there, staff being there, and talking to them directly. And really coming up, you know, really making them bring out that their own progress is there.

Interpersonal themes to engagement

Developing treatment plans, engaging patient’s in daily treatment decisions and enabling patients’ self-reflection, clinicians encourage collaboration; actively engaging the patient and his/her caregiver in the therapy sessions and recovery process.

Organization

Organizational culture and facility rules and regulations were the two facility level factors that were consistently described as influencing patient engagement.

Culture

An organization’s culture can affect clinicians’ and patients’ perceptions and attitudes, which in turn can influence a patient’s engagement in their treatment. Specifically, by establishing an environment where clinicians are empowered to address patients’ needs, patient engagement can be optimized. Clinicians, who view their work as valuable and important, can contribute to building a community in the facility that value their contribution, which can lead to patients and families seeing the importance of clinicians assisting with rehabilitation. Additionally, facilities can promote patient engagement through encouraging clinicians to build rapport with patients and their families. One clinician described the culture of his current facility and compared it to other SNFs where he has previously worked that did not have the same culture,

The most important thing is having a staff that gives a darn about what these people are doing, that are doing it right [as we do here]. If you have people working 8 to 5, punch in, punch out, they’re just doing a job [where he used to work]. It’s having an atmosphere. It’s very relaxed. You really want to create an atmosphere where a patient is feeling welcome and they want to be here, as opposed to having it be a sterile gym. And they’re put through the ringer and sent back [to the facility] in a month. If we give them the personal care, if we ask, act like we care about these issues that we’ve just discussed [in therapy sessions], it makes a big difference. And that really is reflective. I think that is key to a successful department; is one where that philosophy there. The patients sense it, families sense it.

However, the culture of care in the facility can also be a hindrance to post-acute care patients and their recovery process. Facilities that have a long history of caring for long-stay custodial patients, without embracing and understanding the different care needs of a short-stay post-acute care population, can be a barrier to achieving community discharge. Specifically, while long-stay patients’ care is focused on maintenance and staff assisting them, short-stay rehabilitation patients’ care should be driven by a culture of recovery and increased independence, where patients progressively do more for themselves. Within the facility, if there is not a clear understanding of the goals and care needs of short-stay patients, the individual can learn to rely on the staff, embracing the long-term care institutional culture, becoming dependent and thus not increasing dependence and progressing in their recovery:

[This] facility provides excellent care of the patient. Amazing. So they [the rehabilitation patient] get used to it [everything done for them]. They don’t want to go back home. So it’s - different culture.

The attitudes, values, and beliefs embedded in the culture of a facility can affect the patient’s willingness to engage in their rehabilitation, acting as both a barrier and facilitator to engagement.

Rules and regulations

The second theme addressed the rules and regulations established by the SNF. For example, one clinician described the facilities policy regarding rehabilitation’s initial contact with the patient after admission, [patients] are supposed to be seen in the first 24 hours and have therapy in there talking to them [the patient] right away. This initial contact was frequently described as an important process for developing a collaborative relationship with the patient from day one to foster engagement, allay any anxiety described previous, promoting understanding regarding how therapy works in the facility, and initiating the treatment plan discussion from the outset.

Public Policy

The most common theme that was discussed throughout all focus groups was the impact of insurance on patient engagement. Under fee-for-service Medicare Part A, patients have coverage up to 100 days, as long as, there is a documented medical need by the clinicians in the facility. However, at the time of this study, Los Angeles County was transitioning their Medicare-Medicaid dual eligible patients to a managed care health plan, a capitated payment model. Under this capitated model, health plan case managers oversee the patients’ care and play a role in determining when a patient will be discharged to the community. As a result, study participants were experiencing a growth in the number of patients admitted with Medicare managed care instead of fee-for-service Medicare, which was impacting how care was delivered, in particularly discharge planning.

Insurance

A key barrier that emerged from the study was a lack of patient’s knowledge, particularly on their health insurance coverage and insurance policy. With the shift in managed care, clinicians discussed the influence on community discharge for patients and patients lacking knowledge on this change. As one clinician describes a Medicare managed patient:

Because I work in the facility, they’re very blatant. Last day of therapy and the discharge date. So, in our documentation, it’s not me who is discharging the patient, it’s your case manager discharging you from therapy. So it’s a totally different thing. I’m recommending more therapy for you because [I believe] the patient would come back. ‘Hey, I’m not ready to go home yet. I’m in pain. I’m still bleeding. I’m not functioning well.’ And then the patient would come back, and, ‘Hey, I did not discharge you. It’s your insurance that does not want you to be here for therapy.’

Insurance can often be a barrier for patients if they do not understand the policies around their health coverage, specifically with transition from Medicare fee-for-service to managed care. Thus, it can impact a patient’s opportunity to engage in their healthcare because they do not have the opportunity to make their own decisions when insurance policies control their healthcare utilization.

Discussion

Guided by the social ecological model, this study illustrates the complexity of addressing patient engagement in post-acute care. Numerous facilitators and modifiable barriers were identified by clinicians in multiple levels of the model, which can be utilized to increase patient-centered care in post-acute care.

An individual’s motivation, anxiety, and cognitive abilities can influence the patient’s ability to engage in their own healthcare (Bottles 2012). In order to promote patient engagement, patients have to be informed about their healthcare to make appropriate decisions. Patients who lack knowledge of their healthcare services are more likely to have poorer health outcomes (Berkman et al., 2011). Thus, by equipping patients with knowledge about their healthcare experience; anxiety and uncertainty can be decreased, thereby situating patients to engage in their own care, which has been found effective in interventions for other healthcare settings (i.e., primary care) (Kinnersley et al., 2007). Similarly, by engaging patient’s families and caregivers, they can assist in collaborating with clinicians in developing healthcare plans for patients, which can be beneficial for patients who are cognitively impaired (Rowe, 2012). Additionally, fear of falling was a common individual characteristic that clinicians described as limiting patient engagement. Fear of falling can be debilitating and prevent patients from participating in their healthcare, which indicates that it needs to be assessed and treated in every patient (Visschedijk et al., 2010).

The themes that emerged at the interpersonal level reflect current literature indicating clinician-patient collaboration is associated with improved health outcomes (Street et al., 2009). Similarly, the relationship between the clinician and patient is important because clinicians are able to support patient engagement by promoting personal autonomy for the patient (Entwistle et al., 2010). Clinicians are able to provide patients the opportunity to actively participate in their healthcare by eliciting patient’s goals and expectations for their rehabilitation and daily therapy sessions. Additionally, clinicians who are equipped with appropriate informational tools are well situated to educate patients on healthcare services and how to navigate the healthcare system.

The facility’s organizational structure can also influence patient engagement. A teamwork culture, one that is focused on collaboration, has been shown to lead to patient satisfaction of the overall health services experience, which is reflective of the clinicians in our study who emphasized the importance of having a culture focused on patient engagement (Meterko et al., 2004). Facilities need to have rules and regulations in place that provide support for clinicians to work with patients and their families/caregivers. By educating all clinicians on how to communicate and collaborate with patients on treatment plans, facilities can develop a culture facilitating patient engagement (Hibbard et al., 2013).

At the public policy level, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has focused on patient engagement as a vital part of healthcare reform, and is the first step to promoting patient engagement. The lack of knowledge about healthcare policies and the structures of health insurance can limit the patient’s opportunities to engage (Cebul et al., 2008). Changes need to be made in dissemination of clear and simple information and tools for patients to understand the changes in healthcare reform, such as insurance policies, that affect their healthcare service use. Additionally, with the transition from a fee-for-service model to managed care, tools to assist facilities and clinicians can also be developed to help clinicians provide care for patients within a different model of care. Implementing patient-centered policies can help facilitate patient engagement in the other subsequent levels of the social ecological model.

Limitations and Future Research

There were limitations to this study. The study was limited to SNFs in Los Angeles County and did not include other post-acute care settings (e.g., inpatient rehabilitation facilities), which may limit its generalizability. Additionally, this study only included perspectives from clinicians who treat patients with hip fracture. Thus, future research is needed to understand perspectives on patient engagement from different stakeholders, such as patients, caregivers, and nursing staff. The findings from this study are also a result of a secondary analysis and future research is needed to further explore patient engagement in post-acute care. Research is also needed to examine how the multiple levels of the ecological model interact to influence patient engagement.

Conclusion

This study illustrated how patient engagement can be influenced by individual characteristics, patient-clinician relationships, organizational culture, and public policy. By taking a patient-centered approach, in which clinicians build rapport and provide opportunities for the patient to collaborate in his/her rehabilitation, the patient can be invested in their care plan and actively participate in his/her rehabilitation. Given the emphasis on delivering patient-centered care, occupational and physical therapy practitioners are well positioned to assist patients and caregivers in making informed decisions about their treatment plan. Additionally, in the context of healthcare reform and the priorities of the ACA, which emphasized enhancing overall quality of care, patient engagement allows for the delivery of high quality care. By enabling patients to engage in their healthcare, it can contribute to delivering patient-centered care and improving healthcare quality.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Leland was supported by the Rehabilitation Research Career Development (RRDC) Program, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (K12 HD055929) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K01 HS 022907).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: Authors do not have a financial or proprietary interest in materials presented.

References

- Ackerly DC, Grabowski DC. Post-acute care reform–beyond the ACA. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370(8):689–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaupre LA, Binder EF, Cameron ID, Jones CA, Orwig D, Sherrington C, Magaziner J. Maximising functional recovery following hip fracture in frail seniors. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2013;27(6):771–788. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottles KMD. Physician Leaders Should Embrace Patient Engagement/Activation. Physician Executive. 2012;38(6):68–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R, Stevens J. Falls and fear of falling: burden, beliefs and behaviours. Age and Ageing. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32(7):513–531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513. [Google Scholar]

- Castle NG. Nursing home caregiver staffing levels and quality of care a literature review. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27(4):375–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cebul RD, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ, Votruba ME. Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the US healthcare system. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2008;22(4):93–113. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.4.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative sociology. 1990;13(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Cribb A, McCaffery K. Supporting Patient Autonomy: The Importance of Clinician-patient Relationships. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(7):741–745. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1292-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health affairs. 2010;29(8):1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Ku LJE. Postacute Rehabilitation Care for Hip Fracture: Who Gets the Most Care? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(10):1929–1935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Elwyn G. Don’t blame patients, engage them: transforming health systems to address health literacy. Journal of health communication. 2014;19(sup 2):10–14. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.950548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage B, Morley M, Ingber M, Smith L. Post-acute care episodes: expanded analytic file. 2011 Retrieved from Waltham, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Gozalo P, Leland NE, Christian TJ, Mor V, Teno JM. Volume Matters: Returning Home After Hip Fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63(10):2043–2051. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health affairs. 2013;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving Medicare Post Acute Care Transformation Act. Public Law 111-148, HR 4994 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Kinnersley P, Edwards AG, Hood K, Cadbury N, Ryan R, Prout H, Butler C. Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. The Cochrane Library. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004565.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leland NE, Gozalo P, Christian TJ, Bynum J, Mor V, Wetle TF, Teno JM. An Examination of the First 30 Days After Patients are Discharged to the Community From Hip Fracture Postacute Care. Medical Care. 2015;53(10):879–887. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leland NE, Lepore M, Wong C, Chang SH, Freeman L, Crum K, Nash P. Delivering high quality hip fracture rehabilitation: the perspective of occupational and physical therapy practitioners. Disability and rehabilitation. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1273973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie A, Perry L, Lockhart E, Cottee M, Cloud G, Mann H. Family carers of stroke survivors: needs, knowledge, satisfaction and competence in caring. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(2):111–121. doi: 10.1080/09638280600731599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks R. Hip fracture epidemiological trends, outcomes, and risk factors, 1970-2009. International Journal of General Medicine. 2010;3:1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health education quarterly. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370(8):692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEDPAC. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2015 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Meterko M, Mohr DC, Young GJ. Teamwork culture and patient satisfaction in hospitals. Medical Care. 2004;42(5):492–498. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124389.58422.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millenson ML, Macri J. Will the Affordable Care Act move patient-centeredness to center stage. Urban Institute Policy Brief 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Oghalai TU, Kuo Y-f, Zhang DD, Graham JE, Goodwin JS, Ottenbacher KJ. Discharge Setting for Patients with Hip Fracture: Trends from 2001 to 2005. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society [H.W. Wilson - SSA] 2008;56(6):1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK. Qualitative and mixed methods in public health. Sage publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parker M, Johansen A. Hip fracture. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2006;333(7557):27–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7557.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law 111-148, HR 3590 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum S. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Implications for Public Health Policy and Practice. Public Health Reports. 2011;126(1):130–135. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. Great expectations: a systematic review of the literature on the role of family carers in severe mental illness, and their relationships and engagement with professionals. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2012;19(1):70–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient education and counseling. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki G, Stier-Jarmer M, Grill E, Melvin J. Rationale and principles of early rehabilitation care after an acute injury or illness. Disability and rehabilitation. 2005;27(7–8):353–359. doi: 10.1080/09638280400014105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visschedijk J, Achterberg W, van Balen R, Hertogh C. Fear of Falling After Hip Fracture: A Systematic Review of Measurement Instruments, Prevalence, Interventions, and Related Factors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(9):1739–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Roter DL, Given B, Gitlin LN. Optimizing patient and family involvement in geriatric home care. Journal for healthcare quality : official publication of the National Association for Healthcare Quality. 2009;31(2):24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2009.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JP, Connelly DM, Maly MR. ‘Getting back to real living’: a qualitative study of the process of community reintegration after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0269215510375901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]