Abstract

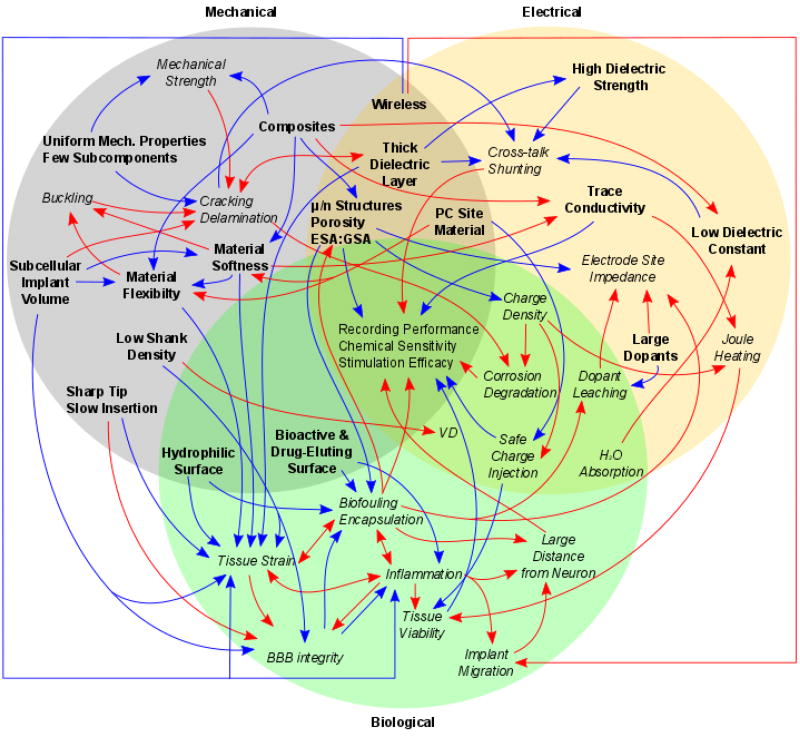

Advancement in neurotechnologies for electrophysiology, neurochemical sensing, neuromodulation, and optogenetics are revolutionizing scientific understanding of the brain while enabling treatments, cures, and preventative measures for a variety of neurological disorders. The grand challenge in neural interface engineering is to seamlessly integrate the interface between neurobiology and engineered technology, to record from and modulate neurons over chronic timescales. However, the biological inflammatory response to implants, neural degeneration, and long-term material stability diminish the quality of interface overtime. Recent advances in functional materials have been aimed at engineering solutions for chronic neural interfaces. Yet, the development and deployment of neural interfaces designed from novel materials have introduced new challenges that have largely avoided being addressed. Many engineering efforts that solely focus on optimizing individual probe design parameters, such as softness or flexibility, downplay critical multi-dimensional interactions between different physical properties of the device that contribute to overall performance and biocompatibility. Moreover, the use of these new materials present substantial new difficulties that must be addressed before regulatory approval for use in human patients will be achievable. In this review, the interdependence of different electrode components are highlighted to demonstrate the current materials-based challenges facing the field of neural interface engineering.

Keywords: Bioelectronics, Electrodes, Microelectromechanical Systems, Sensors/Biosensors, Photonics

Graphical abstract

Neural interface engineering aims to apply advanced functional materials to seamlessly integrate neural technology with the nervous system in order to restore brain function in patients and uncover at least some of the brain’s mysteries. This review highlights the challenges and interdependence of material components for long-term functional performance, and compiles a “roadmap” to guide materials-based neural interface engineering.

1. Introduction

Implantable neural interfaces are important tools for capturing and modulating the sophisticated computations of the nervous system. This technology has seen an explosion in research, innovation and potential applications. In order to better understand plastic changes in neural networks, these interface components must maintain stability over the long time periods associated with memory formation and learning.[1] Clinical scientists have also applied knowledge gained from basic neuroscience studies to develop interfaces with the nervous system for therapeutic or assistive purposes in patients with injury and disease.[2–4] For example, electrical stimulation using implantable neural interfaces –or neuromodulation devices– have received FDA market approval for the treatment of a diverse set of conditions including epilepsy, depression, Parkinson’s Disease, sleep apnea, blindness, deafness, obesity, urinary and fecal incontinence, and hypertension. Patients have also used similar devices to detect and direct brain signals to control robotic limbs, bypassing their injured or degenerated spinal cord.[3–4] While these clinical successes highlight the potential of these technologies, concerns over large variability in therapeutic/assistive efficacy, long-term reliability, and health risks[5–8] prevent these devices from reaching their full potential. This article reviews the recent advances and continued materials based challenges of this rapidly expanding field.

1.1. Neural Signals

The success of an implanted neural interface is contingent upon the quality of the signals that the interface can detect from the nervous system, as well as the reliability and precision with which the interface can modulate the nervous system. Extra-cellular neural recordings can be used to isolate individual neuronal action potentials (also known as “single-units” or spikes), which represent the most basic code in neuron communication. Extra-cellular recordings that do not isolate individual action potentials are called multi-unit recordings which arise when two or more single-units from different nearby neurons are recorded simultaneously. Finally, local field potentials (LFP) are generated by the summation of neural activity from a large population of neurons within a spatial region. LFP is often comprised of low frequency oscillations (0.1 Hz – 120 Hz) that are less sensitive to spatial interference. For neuroprosthetics applications, single-unit and multi-unit recordings are often preferred over LFPs, due to the specificity of the information conveyed but all have demonstrated useful read-out information.

Although neuronal signal transduction is electrical in nature, it is propagated at each axon/dendrite terminal, called a synapse, by the release of neurotransmitters. Unlike action potentials and LFPs, neural chemical sensing electrodes are specific to certain electroactive neurotransmitters such as dopamine or adenosine. These biosensors rely on a technique called Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) to measure the concentration of molecules based on their reduction potential. While these devices do not operate in the same temporal domain as traditional electrodes, their sensitivity to neurotransmitter-specific signaling is critical for assessing the activity from these types of neurons. Neurochemical recordings utilizing FSCV electrodes have been obtained in human patients by multiple groups,[9–10] and have been proposed as a fundamental human research tool as well as a critical sensing component for closed-loop neuromodulation systems.[11–12] When combined with traditional electrophysiological recording modalities, FSCV neurochemical measurements can be instrumental in understanding the complex multimodal therapeutic effects and limiting side effects from neuromodulation therapies to treat psychiatric disorders.

In addition to sensing electrical current or neurochemicals, electrode-based neural interfaces can also be used to introduce signal into the nervous system by injecting current into local tissue (0.1 Hz to >10,000 Hz). Electrode designs can vary dramatically depending upon the anatomical location and therapeutic application for stimulation. For example, simple bipolar or tripolar electrode configurations are typically used to stimulate the vagus nerve for epilepsy and depression, while indwelling microcortical arrays with hundreds of electrode sites are used to provide sensory feedback for a prosthetic.

Recent advances in genetics have expanded the neural interface toolset beyond electrode-based technologies. Optogenetics combines genetics with light-sensitive proteins to instill membrane channels or activity reporters in selective cell populations. Genetic targeting provides a level of control not possible with traditional electrode technology and is attained using several approaches. A common approach is to rely on specific promoters that regulate the expression of genes in cells targeted by the promoter. Major constraints for optogenetics are the requirement for genetic manipulation, the limited availability of promoters, and the potential variability of genetic transcription. Many of the biological challenges for optogenetics are due to poor control over the number of transgenes inserted into the genome, gene insertion loci, promoter enhancers/inhibitors/silencers activity based on insertion loci, and for virus optogenetics, trade-offs between diffusion radius and transduction rates.[13] In addition, due to biophysics and protein kinetics limitations, high sensitivity opsins will have slower channel kinetics while fast opsins will have lower sensitivity.[14] For the purpose of this work, the focus will be on the challenges in delivering and extracting light over the desired spatial resolution with implantable devices (section 2.15). However, it is critical to understand that optogenetic control will be an ongoing challenge for both biological engineering and materials engineering of neural interfaces.

In general, neural interfaces intended to stimulate nervous tissue or record neural activity from the nervous system face a similar material based challenge. The fundamental goal is to enable a higher number of input/output channels from the nervous system, while only creating a minimal disruption of tissue. Avoiding tissue damage is important both for the long-term patency of the interface as well as for minimizing safety risks to the patient. As will be explained in subsequent sections, this fundamental trade-off motivates a number of interdependent design choices with interactions that are often not considered.

1.2. Current Challenges

Current challenges with chronically implantable neural interfaces can largely be categorized into performance reliability and variability issues. Invasive surgical procedures to implant chronic neural interfaces carry inherent risks, such as brain infection, surgery related hemorrhaging, blood clots, edema, etc. As such, these interfaces would ideally be designed to minimize tissue trauma, remain both functional and biocompatible for the life-time of the patient to avoid corrective surgery or re-implantation, and be removable in the event of unforeseen complications. Across all neural implant classes, there is an average decline of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the communication between the nervous system and neural interfaces over time. The resulting decline in neural interface reliability is believed to be, in part, due to the inflammatory tissue response triggered by the surgical implantation procedure. This initial reaction can progress into a chronic immune response, ultimately turning into a foreign body response and even leading to migration of the tissue or implant.[7, 15] While the details of the biological challenges with chronic neural interfaces have been discussed elsewhere,[8] this reactive tissue response degrades the electrical characteristics of the interface by forming a high impedance encapsulation sheath in conjunction with neural degeneration. This response decreases the amplitude of the detected neural signals by increasing the minimum distance from the electrode to the nearest neuron firing action potentials, thereby increasing the applied current necessary for exciting nearby neurons, and limiting the precision of activation via electrical stimulation.[16–17] A number of acute and delayed stab wound studies show that the tissue can recover to some extent when the device is removed,[17–20] suggesting that certain physical properties of chronically implanted neural interfaces are responsible for this tissue reaction.[20]

The focus on minimizing the foreign body response has increased the emphasis on studying advanced materials to overcome specific design parameters hypothesized to attenuate the inflammatory tissue response (see reviews[8, 21–28]). However, large histology and recording performance variability[8, 29–34] have made it difficult to disentangle contributions from the many physical properties of these devices to the myriad of observed multi-modal failure modes.[5, 8, 35–37] These complex failure modes produce histological outcomes that, in isolation, are poor predictors of actual performance outcomes as measured by brain-machine neural communication with high degrees of freedom and SNR.[34–35] Similarly, for stimulation electrode sites, small amounts of platinum particulates expelled over the course of stimulation, and the resulting foreign body response, have not been linked to any additional clinically adverse tissue reaction beyond those of a recording electrode.[38–41] Current literature often highlights the advances of individual material properties and therefore has a limited discussion of the broader obstacles limiting the advancement of the field. While excellent reviews can be found on advancing individual design properties[21–28, 42] or expanding upon the biological tissue reaction,[8] this review aims to highlight the interdependence of multiple design and material properties as well as to guide the success of balancing and titrating these properties. Through this multi-dimensional cost-benefit analysis, engineers can design functional neural interfaces capable of obtaining selective, high-fidelity, long-lasting readouts of brain activity. Material selection, the design and assembly of the materials, and strategies for surgical delivery of the implantable components will likely provide critical breakthroughs in achieving improved device performance.

2.0 Material Considerations for Engineering

The simplest electrode design consists of a conductive component to transfer electrical charge, insulation to spatially constrain neuronal signals, and a connector that provides external interfacing with signal processing devices. However, there are numerous intrinsic material properties (conductivity, flexibility, material strength, and chemical stability) as well as extrinsic design parameters (geometry, density, insertion, and packaging) that must be considered to achieve long-term biocompatibility and functionality. These individual intrinsic and extrinsic properties are interdependent on one another and optimizing one can negatively impact overall performance or lead to loss of functionality. The goal of this review is to introduce a number of the key material and design properties as well as their complex interdependence on one another. Understanding these engineering challenges are critical for the development of devices with long-term functionality.

2.1. Electrical Property/Electrode Traces

One of the most important components of any electrode technology is the conductor, which forms the electrical connection, also known as electrical trace, that carries current (Figure 1a). Every electrode must include a conductive element which transfers detected signal from the tissue to an external electrical device, such as a headcap for cortical recording electrodes, or transmits current to electrode site to a percutaneous connector or transducer. The conductance (G) is the material property that describes the ease with which charges can move within it:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where R is the resistance of the conductor, A is the cross-sectional area of the conductor, l is the length, σ is the electrical conductivity in siemens per meter (S·m−1), and ρ is the electrical resistivity or specific electrical resistance (Ω·m).

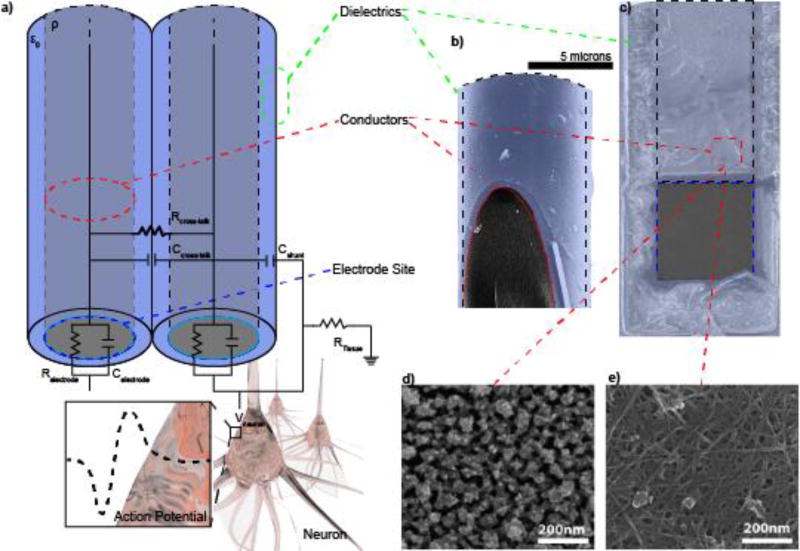

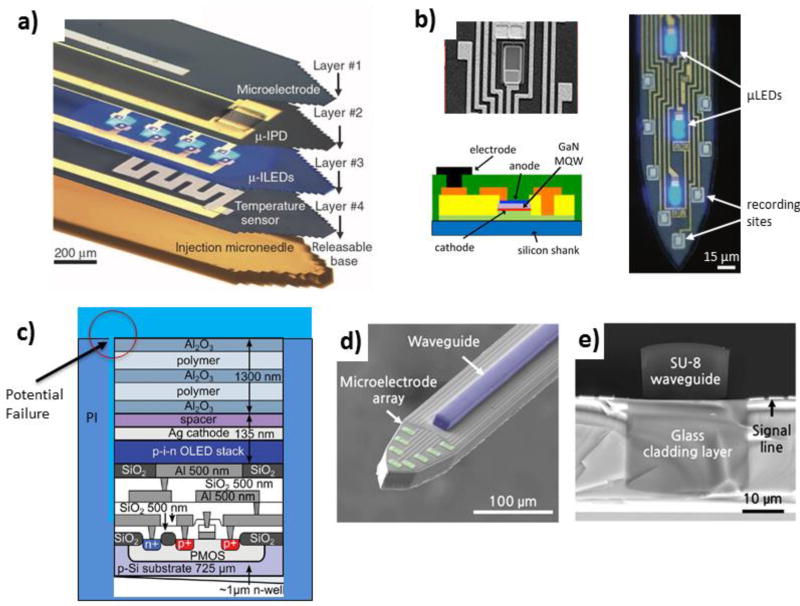

Figure 1. Basic Electrode Anatomy.

a) Randles circuit representation of the electrode, which includes the electrode trace (red dash), insulation (green dash), and electrode site (blue dash: Relectrode and Celectrode) where neural potentials (Vneuron) are recorded from. Note: Post-electrode equipment is not shown. b) Cross-section of a Microthread Electrode[251] showing the carbon fiber core and Parylene insulation. c) Layer-by-Layer (LbL) assembled composite electrodes using Au nanoparticles (d) or carbon nanotubes (e). Reprinted with permission from[569] Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society.

As shown in Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, the dimensions of the material can play a crucial role in determining electrical properties. With the emergence of nanoscale and angstrom diameter wires, it is important to consider how the size of the electrical trace can constrain the maximum signal or stimulation current that can safely be passed through the device. The minimum cross-sectional area (A) is limited by the heating power (P, Joule heating, also known as ohmic or resistive heating), especially for electrical stimulation and chemical sensing electrodes;

| (3) |

where I is electrical current. At some finite A the electric current will produce enough heat that it might burn/oxidize or melt the conductor, reducing its conductivity. Given all of these considerations, specific materials and the method of deposition have unique advantages and disadvantages that should be considered when choosing an electrical trace conductor for particular applications.

Metals, particularly noble metals, are perhaps the oldest and most common electrical conductors used for neural electrodes.[43–44] Their high electrical conductivity originates from the overlapping valence and conductance bands of metal atoms, allowing for relatively free movement of electrons through the solid ‘electron sea’ lattice.[45] Selection of metal conductors requires careful consideration of conductivity, mechanical stability for handling, chemical stability (namely, corrosion resistance), and biocompatibility. In general, heavy transition metals such as gold (Z=79), platinum (Z=78), and iridium (Z=77), as well as tungsten (Z=74) or tantalum (Z=73; for short-term applications) display a number of these desirable properties. The noble metals and alloys can generally remain relatively chemically inert over chronic timescales that would affect other conductor classes.

Advances in microfabrication and photolithography techniques enable well controlled and reproducible batch fabrication, which has led to the use of semi-conductors and polycrystalline materials which are more compatible with these microfabrication processes. Semi-conductors are materials with small band-gaps (between the valence band and conductance band) that can be made conductive by adding electron acceptors (p-dopants) or electron donors (n-dopants) impurities. Polycrystalline materials are composed of small crystalline regions separated by grain boundaries.[46] These grain sizes dramatically impact the conductivity, making them more conductive than their amorphous material counterparts.[47–49] Polycrystalline silicon (Polysilicon) is a highly pure, polycrystalline form of silicon that is easily fabricated into microelectrodes and is compatible with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS)[50] and MEMS[51] technology. Additionally, the conductive properties of polysilicon can be modulated by varying processing conditions or dopant densities.[49] For these reasons, polysilicon is a popular material used in microfabricated silicon arrays. While silicon technology can be more brittle than metal, it offers a greater design space than traditional microwires.

Unlike inorganic semi-conductors, conductive polymers (CPs) are organic polymers that conduct current.[52–57] CPs are composed of monomeric compounds linked in chains of alternating single and double bonds and doped with a stabilizing counter-ion.[58] Conjugated polymers have narrower band gaps, allowing electrons to move easily between the conducting band and valence band. Dopants increase the conductivity of polymers by either removing electrons from the valence band (p-doping) or adding electrons to the conduction band (n-doping). The most common biocompatible conductive polymers used for neural interfaces are Polypyrrole (PPy),[59] poly(ethylene dioxythiophene) (PEDOT)[59] and polyaniline (PAni),[60] with PEDOT being the most electrochemically stable.[28] Most conductive polymers, however, do not contain intrinsic charge carriers and must be doped with a counter ion to reduce electrical resistance and heating, and improve conductance. Therefore, they require counter ions that are partially oxidizing (p-doping) electron acceptor (such as LiClO4, I2, or AsF3) or alternatively partially reducing (n-doping) electron donors such as Na or K. While CPs may be either chemically or electrochemically synthesized,[61–62] careful consideration of the counter-ion’s charge or polarity (zwitterions), and concentration is necessary for electrochemical deposition.[28] Conductive polymers generally have lower conductivity than most metals, but other advantageous properties make them popular for coating electrode sites (see section 2.4).[63] However, recent efforts are aimed at developing conductive polymer composite wires with improved mechanical properties.[64–66] Currently, considerable challenges remain due the brittle deposition of CPs which complicate the fabricattion of electrodes comprised entirely of CPs.

Carbon-based materials (graphene, carbon fiber, carbon nanotubes) are also being developed as the conductive components of electrodes. Some carbon allotropes are highly conductive due to the carbon-carbon pi bonds. Carbon-based materials also have useful mechanical properties such as high tensile strength and modulus. Single carbon fibers (CF) are implemented similarly to metal microwires[67–71] (Figure 1b). Graphene, a hexagonal lattice monolayer of carbon,[72] has exceptional flexibility, surface area, and conductivity.[73] Graphene and graphene oxide (GO) have been implemented as bulk conductors,[73] coatings,[74] and dopants.[75–76] The flat structure of graphene makes it ideal for patterning planar implants.[77–79] Recently developed high aspect ratio all-carbon crumpled graphene transistors demonstrate high sensitivity and improved spatial resolution, with no observed increase in source–drain resistance at up to 56% of compressive strain.[80] In contrast, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are cylindrically-wrapped graphene sheets. Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) are comprised of a single layer and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) have multiple layers. These CNTs are emerging as novel substrates for a variety of neural engineering applications due to their high mechanical strength and electrical properties.[81–83] CNTs also can have a range of electrical properties based on the orientation in which the graphene is wrapped in a tube. This property is represented by a pair of indices (n,m), and it modulates the CNTs’ conductive properties: from metallic, to quasi-metallic, or semiconductive[84–85] (see review[28]). Due to challenges of fabricating long CNTs, they are generally employed for the electrode site materials (see section 2.4),[83] however, there has been some effort in developing and patterning CNT containing composite conductors, such as through layer-by-layer deposition methods for neural interfaces (Figure 1c–e).[28, 86–89] For applications where stretchability rather than flexibility is required, CNT-doped copolymer matrices can achieve up to 130% strain.[90] These composite conductors are engineered by bringing conductive particles close enough for electrons to jump from one particle to another known as percolation networks. The small spaces between each particle can absorb more strain before breakage, improving the mechanical properties of the device. However, the tradeoff is that these small spaces lead to increased resistivity compared to solid metals.

To summarize, ideal conductors should achieve exceptional conductivity, long-term functional durability, electrochemical stability, low cross-sectional area, and the ability to withstand stress and strain forces. As devices become smaller and vary in their geometries, materials that can be handled easily during microfabrication are preferred since their conductive properties can be altered with processing. Metals wires are traditional materials with good conductivity and the ability to be assembled in large arrays, but have limited stretchability. Some other conductors trade compatibility with microfabrication techniques and increased design space for assembly into arrays with increased brittleness. Composite materials generally trade decreased conductivity with increased stretchability and/or durability. Often, the decreased conductivity needs to be compensated by increasing the cross-sectional surface area. As such, for developing functional implants, it is critically important to balance all of these material properties as well as those in the following sections.

2.2. Insulation Materials

The other critical component of chronically implantable microelectrode technology is the dielectric layer, or insulation layer. Some commonly empoyed insulating materials include varnish, epoxy, parylene, glass, Teflon, polyimide, fused silica, silicon oxide, silicon nitride, or silicone elastomers.[28, 91] Dielectric materials generally have a large bandgap between the conductive and valence band, which blocks electrical conduction at low voltages. While the functional component of any electrode is the conductive element, insulating dielectric materials are equally critical to preventing parasitic capacitance from allowing the signal to leak into the tissue or into adjacent conductors. The insulating material property is defined primarily by its resistivity (ρ) and the dielectric constant (εr) or the relative static permittivity. For simplicity one may consider the effect of a dielectric material in a parallel plate capacitor (C):

| (4) |

where ε0 is the electrical constant (ε0 ≈ 8.854×10−12 F·m−1), d is the thickness of the insulation layer, and A is the cross-sectional area of the insulation layer along the electrical trace. Insulating materials are characterized as having a relatively low εr, that is, the ratio of the capacitance of a dielectric material to that of a vacuum which tends to 1. The shunt capacitance (Cshunt, Figure 1a) is the capacitance across the insulation layer from the center of the electrode conductor to the conductive electrolyte bath conductor, which results in an inversely frequency dependent impedance across the electrode, behaving as a low pass RC filter with frequency fc:[92–94]

| (5) |

| (6) |

where ω is the angular frequency of the waveform (rad/s). With respect to equations 3 and 4, materials with high dielectric constants or low dielectric thickness lead to high capacitance, coupling of electrical signal to adjacent traces, and attenuating the recorded signal (Vout-shunt). At very thin dielectric thicknesses, the insulation becomes less effective due to electron tunneling.

For high density arrays, current density accumulation in a wire or electrode can cause a change in current density in adjacent wires through capacitive charging with the two wires acting as the capacitor (Ccross-talk: aka, cross-talk capacitance, capacitive coupling or mutual capacitance, Figure 1a). In multi-channel electrode arrays, cross talk is caused by capacitive coupling of one circuit (the “aggressor”) to another (the “victim”):

| (7) |

where ΔVvictim is the potential change induced by the “aggressor” circuit onto the “victim” circuit, ΔVaggressor is the potential change in the “aggressor circuit”, Cgrd is the total capacitance relative to ground, Cadj describes the capacitor formed between the circuits, Ragressor and Rvictim are the resistive loads of the coupled circuit on the conductors respectively, Cgrd−a and Cgrd−v are the capacitances between the aggressor and ground and the victim to ground respectively. Equivalent circuit models developed for electrodes implanted into tissue show that crosstalk increases the effective amplifier impedance (comprised of the head-stage impedance and shunt capacitance) above the effective electrode impedance (comprised of the resistance of the electrolyte solution as well as resistance and capacitance of the electrode) with increasing signal frequency.[93–94] As a result, crosstalk can attenuate recorded signals, cause false signal in adjacent electrodes during recording, or result in unwanted accumulation of charge density between adjacent electrodes during stimulation.[95–96] This effect is especially prominent in small multi-electrode arrays in which resolution is important, as signal in one wire can affect signals in nearby wires. Inert materials or materials with low dielectric constants, such as ceramics or polyimide, reduce crosstalk compared to other poor insulating materials such as silicon, a more conductive substrate.[97] While the source of cross-talk is traditionally in the interconnects and packaging, it becomes an increasingly important issue as engineers attempt to design higher density arrays.[98]

A number of polymer insulating materials have become popular due to the ability to uniformly and reproducibly coat complex micro-scale shapes, lower elastic modulus, attain chronic stability in physiological environments, and achieve compatibility with other microfabrication techniques for selectively controlled de-insulation of active sites.[99] These include parylene and polyimide variants where the side chains or R groups alter the material’s dielectric, mechanical, and sometimes even bioactive properties.[99–101] Careful selection or combination of functional R-groups can also be used to functionalize bioactive surfaces (see section 2.14). Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is a another insulator for neural tissue interfaces due to its biocompatibility.[102] However, effective PDMS-based dielectrics for implants require substantial thickness due to its high water absorption rate, which increases its dielectric constant and shunt capacitance, and decreases the cutoff frequency. Other polymers with very high water absorption cannot be used as insulation materials for chronic implants. For example, many epoxies are unsuitable for use as insulators for chronic electrodes because it absorbs water, negatively impacting dielectric properties as well as allowing for corrosion conditions in devices utilizing dissimilar metal connections within the insulation, especially under stimulation conditions.[103–104]

Another property that requires consideration, especially for electrical stimulation, is the material’s dielectric strength. Dielectric strength, in contrast to the dielectric constant, decreases with surface defects (pin-hole defects; Figure 2a), increases with temperature, increases with signal frequency, and can decrease with water absorption. Careful consideration of the dielectric property, water absorption, and insulation thickness are important for chronic neural interfaces. At high voltages (on the order of 106 V/cm, the limit increases with decreasing relative permittivity and thickness) dielectric materials ‘break-down’ and become conductive.[105] Exceeding these voltages will usually also lead to other failure modes such as gross degradation or melting.[106] However, for chronic electrical stimulation, lower DC voltages that are either deliberately induced to power active components on the electrode, or naturally arise during stimulation can exacerbate failure of the insulation, especially at points of defects. For example, the increase in time to failure for an Al2O3 and parylene bilayer is 13 times faster when a 5V bias is applied.[107] Also, thin dielectric films risk the possibility of forming a simple low-pass RC circuit. An RC low-pass filter allows frequencies from 0 Hz (DC) to its cutoff frequency to pass while attenuating higher frequencies, which can contain critical single-unit information. In this case, a negative capacitance amplifier can help correct for the various capacitive impedances introduced by the conductor/insulator capacitors.[92, 108]

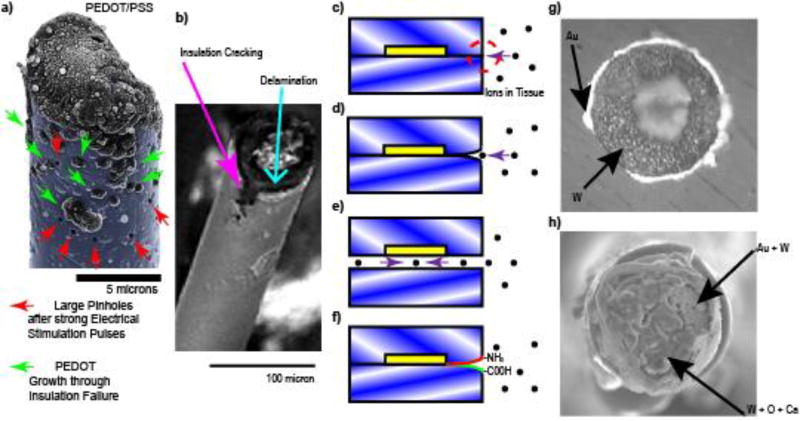

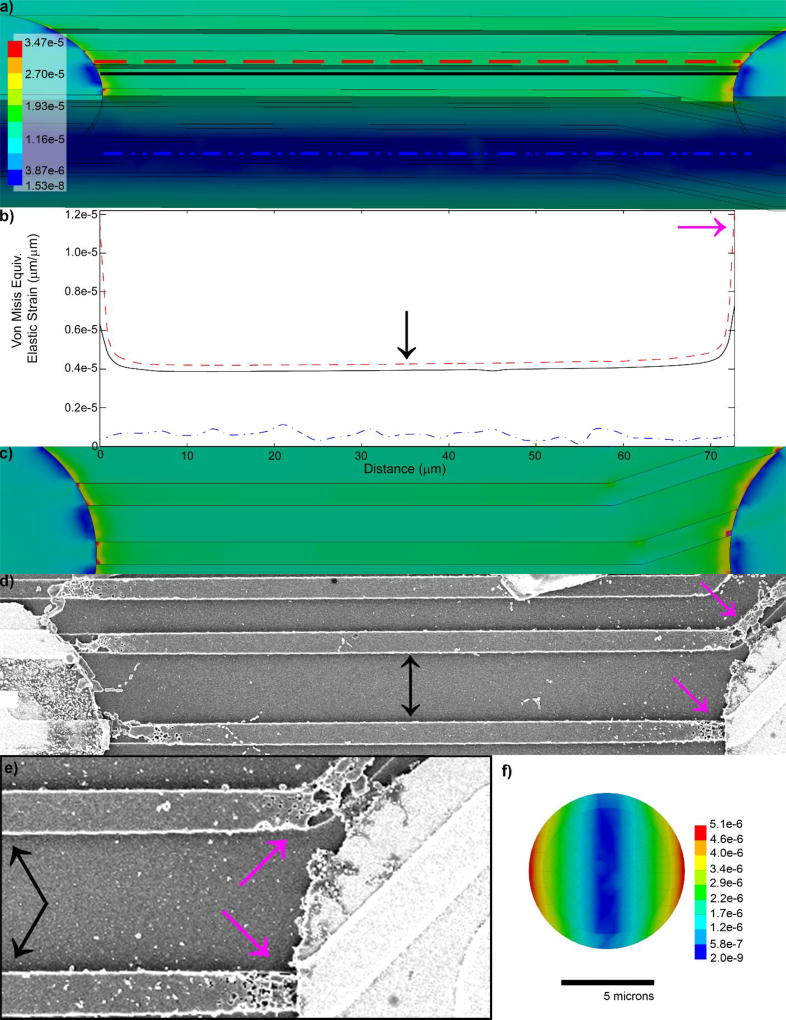

Figure 2. Insulation Failures.

a) Strong stimulation currents lead to insulation failure that starts as pin hole defects (Red Arrow) in the insulation (cyan). Complete Insulation failure (green arrow) can be identified over regions of PEDOT/PSS electrochemical deposition through the insulation (cyan). b) Many dielectric polymers such as parylene are susceptible to cracking (magenta arrow) and delamination (cyan arrow). © IOP Publishing. Reproduced with Permission from[210]. All rights Reserved. c) Planar arrays made from crystalline polymers form triple junctions (red dashed circle) when implanted. The two crystalline layers cannot be perfectly aligned due to entropy (blue/white angles). d) Ions and water molecules in the tissue thermodynamically degrade the interface of the two crystalline layers forming a crack. e) Cracks thermodynamically propagate until insulation fails. Note: this is not an issue if the triple junction crack propagation failure rate is slower than the lifetime of the patient. f) Self-healing smart polymers with self-annealing functional groups and re-seal delamination. g) Insulation adhesion layers (eg. Au) are sometimes used to reduce insulation delamination failures. h) In the tissue, the wire (W), exposed adhesion layers (Au), and the tissue environment creates a galvanic cell, accelerating corrosion. Reprinted with permission from[209] Copyright 2011, Elsevier

Dielectrics are essential in ensuring electrical current travels unimpeded through the conductor preventing any loss in electrical quality through shunting or attenuation. As a result, an ideal insulator would be thin and have a low dielectric constant, high dielectric strength, achieve virtually no capacitance, have minimal potential for water absorption, and are simultaneously thick enough to occlude fluid ingress. These optimal properties would allow small electrical traces to be packed close together, while limiting parasitic capacitance and cross-talk, leading to limited signal loss or attenuation. In addition, the material must be flexible (low Young’s modulus) and remain durable under chronic cycling. Since a wide range of materials fit into the insulator class, other mechanical and adhesion properties must also be considered for applicability to specific electrode designs and functionality requirements.

2.3. Adhesion of the Insulator

During microelectrode production, the insulator is typically either deposited uniformly over the entire conductive material, as in the case of fabricated microelectrodes, or hand-made using backfill in the case of neuromodulatory devices. Active electrode sites are formed by removing insulation in a controlled fashion or by controlling the wire length that protrudes from the insulation sleeve. Exposure methods for microwires, such as mechanical impact, cutting with a razor, pyrolysis (flame), electric arc, plasma arc, and laser can lead to large variability in site size, impedance, and recording quality.[109–113] These methods can also create collateral damage to the surrounding insulation layer, such as cracking and delamination (Figure 2b). Cracking and delamination lead to electrode failure as the geometric area of the exposed conductor becomes too large.[114] This averages the recorded potentials across a larger electrode surface area and attenuates the neural signal (see section 2.4). This underscores the importance of carefully considering the biocompatibility of the underlying materials. For example, many semi-conductors (i.e. gallium or arsenide) are toxic in vivo.[115] While adhesion layer coatings such as Au and Ti have been employed to limit delamination, this can lead to rapid corrosion of the electrode site material (Figure 2g–h; see section 2.5).[116]

A much more controlled approach for exposing the electrode site or depositing the same electrode site is through lithographic techniques, such as through the use of photoresist masks.[117] However, unlike microwires that have conformal coatings of insulation, planar microelectrodes are generally created by sandwiching conductors between two insulation materials. With silicon technology, low pressure chemical vapor deposition of silicon oxide is used to conformally insulate the polycrystalline silicon traces,[118] and provides one of the highest quality SiO2 films available. However, thin films of silicon oxide have a tendency to bow from compressive internal stresses.[119] For this reason, an additional silicon nitride dielectric layer or silicon nitride followed by another silicon oxide dielectric layer are used to balance the bowing and provide additional biostability compared to a single SiO2 layer.[120–121] When two crystalline materials are used to sandwich electrical traces and then are implanted into tissue, a triple junction forms (Figure 2c) often leading to delamination (Figure 2d–e). The thermodynamics of crack propagation at triple-junction sites between crystalline materials has been well studied, especially in electrolytic solutions such as the cerebral spinal fluid.[35, 122–124] One approach to reducing delamination is through thermal annealing, a method that utilizes heat and pressure to improve the seal between two polymer layers.[125] However, this has been shown to impact device performance and sensitivity by influencing bulk polymer properties.[125–126] Polymers that can withstand temperatures near their melting points for longer periods of time such as amorphous (non-crystalline) polymers may be another alternative to forming better thermally-annealed insulators for avoiding triple-junctions. Another approach to prevent crack propagation is through the use of ‘smart’ self-healing materials that can respond to incidences of damage.[127] For example, polymers can be functionalized with reactive chemical species,[128–140] two polymer layers with appropriate functional groups (-CO-NH2 and -COOH) have been shown to self-anneal into imine bonds in vitro that chemically seal two layers together over time without the need for thermal annealing (Figure 2f).[141] In the event of material degradation or delamination, the exposed functional groups may reform covalently through thermodynamic reactions. However, further investigations are required to determine the self-healing potential of these functionalized polymers in vivo. Unlike planer probes that involve polymer-polymer delamination failure, designs such as microwires and bed of needle arrays benefit from being coated with a single conformal layer of insulation. However, these devices still suffer from delamination and cracking at the conductor-polymer interface near their recording sites.[36, 114, 142] Careful material selection and deposition methods are critical for long-term functional performance.

2.4. Electrode size & materials

Electrode site materials and site sizes are important aspects that impact the sensitivity and performance capabilities of neural microelectrodes. Electrode site designs need to carefully consider the electric field strength to selectively attenuate signals resulting from more distant neurons:

| (8) |

| (9) |

where q is the magnitude of the action potential, r is the distance from the source, d is the thickness of the cell membrane, ε0 is the permittivity constant of the tissue, and θ, the angle between the current source and the electrode, is equal to 0. In reality, extracellular action potential characterization depends on the distance between the electrode and the cell, and the radius and dendritic density of the cell.[143] However, in general, empirical measurements indicate that the voltage drop-off is between that of Vmonopole and Vdipole.[144–147] This voltage can be expressed simply by:

| (10) |

where σe is the conductivity of the extracellular space, n is the number of current point sources which the electrode is exposed to, and x is 1 < x < 2 dependending on the size, geometry and type of neuron. Small contact sites (<<1000 µm2) have the advantage of greater selectivity, and can potentially distinguish between multiple single-units with higher signal amplitudes. This is because only a small number of neurons will be within close proximity to small recording sites and detected voltage of distant neurons decay rapidly with r (Figure 3a). However, small electrode sites are impaired by increased impedances and thermal noise from tissue.[145, 148] On the other hand, lowering the impedance by increasing the recording site surface area leads to attenuation of the signal amplitude.[145, 149] (Figure 3a–b) Large sites can be modeled as small sites in parallel with increasing r with distant parallel elements detecting very low V. Voltage elements in parallel are calculated as the average of all parallel elements. As a result, the fall-off of the electric field generated by a nearby neuron is steep; larger electrodes tend to average strong signal from the nearby neuron with weak signals that are more distant, effectively decreasing the signal recorded. Therefore, it is important to select electrode site materials that lower impedance without increasing the geometric site size. For single-unit recordings, the ideal electrode has the lowest possible surface area and impedance.

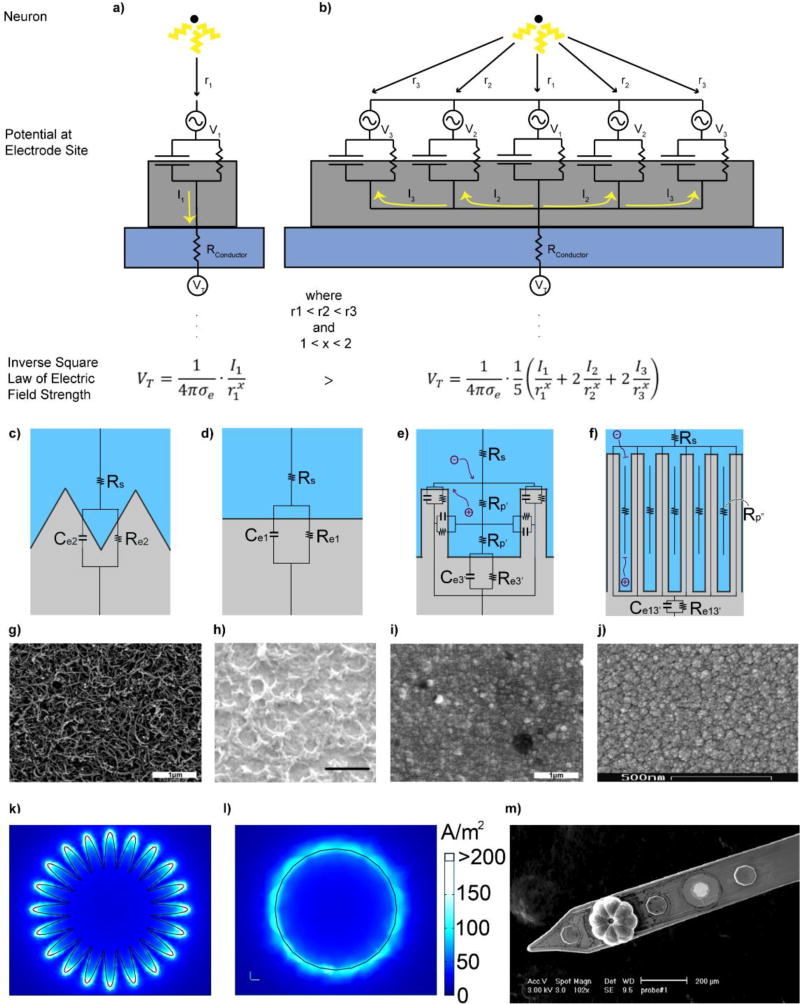

Figure 3. Electrode site size and material properties influence recording and stimulating performance.

A small contact site surface area (a) compared to a larger contact site surface area (b) records larger voltage amplitudes (VT) from a single point source (a neuron) provided by the inverse square law of electric field strength. Note: I2 and I3 are negative. c–f) Charge transfer during electrical stimulation with varying geometric surface areas at the electrode interface. Increasing surface area from (c) to (d) increases the capacitance (Ce2 > Ce1) and halves the resistance (Re1 > Re2). Creating a pore (e) introduces a resistance (Rp’) with a cross-sectional area of A and length l. Increasing pore length from (e) to (f) begins to impact ion movement within the electrode-tissue interface and attenuates electrode performance. g–j) SEM images of electrode site materials: PEDOT/CNT, scale bar 1 µm (g), PEDOT/GO, scale bar 1 µm (h), PEDOT/PSS, scale bar 1 µm (i), and IrOx, scale bar 500 nm (j). Reproduced with permisison from[238],[75], and[570] Copyright, 2016, 2013, and 2010 from IEEE, the Royal Society of Chemistry, and Elsevier, respectively. k,l) Distribution of charge density representing the edge effect for a planar high-surface area electrode (k) and circular electrode (l). Adapted with permission from[183]. Copyright 2009, Frontiers Media SA. m) Recording site electrochemically deposited with polypyrrole (PPy). The octagonal recording site geometry allowed the polymer to grow into eight teardrop segments with an absence of coating from the center. (c–f,m) Reprinted with permisison from[28] Copyright © 2014, Springer Science+Business Media New York

Stimulation electrodes require additional material considerations. The electrode site material and stimulation amplitude on stimulating electrodes determine whether the electrode is capacitive (non-faradaic), involving electrostatic or electrolytic interactions between the electrode-electrolyte interface, or faradaic, which involves redox reactions between the electrode and surrounding medium.[92, 150] Non-faradic electrodes stimulate neurons through the diffusion of ions by charging and discharging the capacitive layer that forms at the electrode surface, which is considerably safer than faradic charge injection methods since the electrode material is chemically stable. Non-noble metals, such as titanium, tantalum, and stainless steel metals inject charge mainly through this double layer capacitance.[151] However, there are charge transfer limitations compared to faradaic electrode materials.[152–153] Irreversible faradic interactions occur when oxidized ions diffuse away from the electrode before they can be reduced and redeposited onto the electrode site, which is called electrode dissolution and can have harmful effects on the surrounding tissue.[154] This is particularly true with metals that generate low molecular weight ions during stimulation. Noble metals such as platinum (Pt), iridium (Ir), palladium (Pd), and rhodium (Rh) are used during neural stimulation due to their corrosion resistance.[155–156] While platinum and iridium have limitations on charge injection capacity,[157–158] platinum-iridium alloys improve mechanical and electrochemical properties, making them suitable as implantable interfaces. Another concern during tissue stimulation is the formation of hydrogen and oxygen gas through the electrolysis of water. The potential range that occurs before the reduction of water (H2 formation) or oxidation of water (O2 formation) is defined as the water window. Platinum electrodes have reported charge injection limits between 50–150 µC/cm2 using biphasic 0.2 ms pulses, safely within limits of the water window.[159] However, platinum dissolution has been shown to occur at as little as 20 µC/cm2 so alternative parameters during stimulation must be carefully considered.[160]

On the other hand, pseudocapacitive electrodes are made from electrode materials that transfer charge through faradaic modes, but some of these metal ions can be reversed back onto the electrode before the ion diffuses away by rapidly applying the opposite charge. These electrode materials are sometimes considered ideal stimulating electrode materials because their method of charge injection involves reversible redox reactions that avoid the harmful dissolution of metal ions but have high charge transfer capabilities. For example, iridium oxide (IrO2) electrodes are used for their mixed conductivity and reversible Ir3+/Ir4+ redox reactions that permit charge injection capacities of about 0.5–8 mC/cm2.[161–162] Sputtered iridium oxide films (SIROF), electrodeposited iridium oxide films (EIROF), and activated iridium oxide films (AIROF) generate the same iridium oxide as an electrode material, but with widely different surface morphologies.[163–165] Other common materials for pseudocapacitors include transition metal oxides, nitrides, and sulfides such as manganese (MnO2), iron (Fe3O4), titanium nitride (TiN), and titanium sulfide (TiS2).[166–172]

While many safe stimulation electrodes exist, they are limited in their ability to spatially and selectively activate small populations of neurons.[173] Ideally, a stimulation electrode will have a very small surface area such that it minimizes activation of nearby axons and neurons to a locally confined area.[28, 174–176] However, attempting to increase specificity by lowering the geometric area results in higher charge densities (Q/A) that can damage tissue.[177–179] To address tissue safety issues, most stimulating electrodes are designed to have large surface areas. One way to safely alter the electrical properties of both recording and stimulating electrodes is to increase the electrochemical surface area (ESA) relative to the geometric surface area (GSA) (Figure 3b–d). The ESA of a probe involves introducing micro- and nanoscaled features that alter the roughness and porosity of the surface of the electrode, improving charge transfer with the surrounding electrolyte solution. Likewise, increasing ESA lowers impedance,[180] so charges of equivalent amplitude can be injected with lower electrode potentials, decreasing the risk of tissue damage. However, there is an upper limit to increasing the ESA, since at some point ions diffusion through the pore become negatively impacted (Figure 3e). For a sinusoidal AC waveform, the penetration depth λ into the pore of a rough surface can be modeled as:

| (11) |

where r is the pore radius (cm), κ is the electrolyte conductivity (1/Ω cm), cd is the surface capacitance (F/cm2), and ω is the angular frequency of the waveform (rad/s). For a given frequency ω, there will be a maximum penetration depth λ at which increasing the surface area beyond this distance will not influence charge transfer, due to resistance of ionic current as a result of increasing pore length(Figure 3e).[181] Likewise in chronic implants, resistance of ion diffusion across the coating can be exacerbated in vivo as reactive tissue and cells block pores across the surface of the electrode, likely overriding any beneficial enhancements over time from increasing the electrochemical surface area.[182] Lastly, it may be worth considering how the geometry of the electrode site leads to an “edge effect”, where charges are more concentrated on the edges of an electrode during stimulation due to repelling like charges,[183–184] leading to preferential corrosion at the edges of the electrode site (Figure 3k–j).[185] Therefore, even when relatively safe stimulation parameters are followed, irreversible redox reaction may still occur at the edges which may lead to corrosion of the electrode, damage of the tissue, as well as facilitate the delamination of the electrode sites from around its edges.

One method of increasing the ESA:GSA ratio to reduce impedance is with CNT, graphene, CP coatings, or other nanostructured surfaces (Figure 3f–j).[28, 81–83, 117, 186] While these materials generally have lower impedances per electrochemical surface area compared to many metals, they are easier to deposit with high ESA. For stimulation, CPs require more careful consideration of the counter ion.[187–188] Among the CPs, PEDOT is considered to be the most stable electrically conducting polymer coating that has demonstrated decreased impedance, similar charging injecting capabilities to iridium oxide electrodes, biocompatibility with tissue, and long-term mechanical stability in vivo.[28, 189–190] Doped CPs have the potential for high storage capacities. PEDOT doped with paratoluene sulfonate (pTS) can produce charge storage capacities of about 130 mC/cm2.[191] The specific dopant and deposition parameters can dramatically alter the surface morphology of the electrode thus influencing charge capacities. For example, poly(styrene sulfonate) (PSS)-doped PEDOT electrodes display a reduced storage capacity of about 100 mC/cm2.[191] These polymers can also be chemically modified to form a plethora of derivatives, each with unique electrochemical and biological properties(see section 2.14).[192]

In contrast to stimulating electrodes or electrodes to record electrophysiological signals, electrodes used to measure electroactive neurochemical concentrations using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) are critically dependent on the interaction between the electrode surface and adsorbed electroactive neurochemicals of interest.[193] FSCV measurements typically consists of two steps: 1) a small DC holding potential is applied to the electrode to promote adsorption of neurochemicals of interest to the electrode surface while repelling confounding interferents and 2) the application of an approximately 10 ms triangular voltage pulse that sweeps from −0.4V to 1.5V back to −0.4Vs (the cathodic/anodic limits and sweep rate may vary based off of the neurochemical of interest and electrode material). The triangle voltage pulse causes electroactive neurochemicals adsorbed to the surface to oxidize and reduce at specific potentials creating brief peaks in faradaic current that can be used to identify specific neurochemicals and changes in their concentration. Consequently, materials used for FSCV materials must 1) enable small electrode designs that minimize biofouling/scarring that would prevent the adsorption of the neurochemical to the surface, 2) minimize the number of other electrochemical reactions that occur at the surface that could confound measurement of the neurochemical of interest, 3) have minimal drift in open circuit potential that would generate variability in the true voltage applied during the FSCV pulse, and 4) be able to both adsorb the neurochemical of interest while allowing the neurochemical to desorb once oxidized/reduced so that changes in local concentrations of the neurochemical can be monitored over time.[194] The ultimate goal is for the FSCV electrode to have both high sensitivity (detect low concentrations of a neurochemical) and high selectivity (able to differentiate the neurochemical of interest from interferents).

The traditional electrode material for FSCV recordings are small carbon fiber electrodes, which can also be cycled at high levels to deliberately cause dissolution of carbon at the surface. This removes biofouling and uncovers new unoccupied sites for adsorption to enhance signal in a chronic environment.[195] Numerous alternatives to traditional carbon have been studied including noble metals like gold, platinum/iridium, iridium oxide, conductive polymers, boron-doped diamond, graphene, and pyrolyzed photoresist.[196–204] Boron-doped diamond is a promising material for chemical sensing due to its good conductivity, chemical stability, and biocompatibility, but it has a low double-layer capacitance that is not ideal for electrical stimulation.[205–206] Some of these newer materials like boron-doped diamond have yet to demonstrate sensitivity comparable to carbon fibers. For other new materials the inherent drift in electrochemical reactions at the surface of the material over time ultimately limit sensitivity, or the inability of the neurochemicals of interest to desorb after oxidation/reduction once adsorbed dramatically decrease sensitivity over time. FSCV waveforms and subsequent analysis to maximize sensitivity and selectivity utilizing a small carbon fiber electrode was optimized over the course of decades, while the same degree of optimization for other material candidates has yet to be performed. Of the recently explored new materials, pyrolyzed photoresist, which behaves the most like traditional carbon but is more amenable to modern multi-electrode fabrication processes, is arguably the most promising.

2.5. Chemical Stability of Materials

Developing chronically implantable devices require careful selection or development of materials and assemblies that outlast the lifetime of the subject. When the adhesion layer (e.g. Ti underneath Au or Ir) or the interface of the conductor and electrode site material becomes exposed to the tissue (due to dielectric cracking, delamination, electrode site dissolution,[207–208] or general preparation), the tissue fluid and the two separate metals form a short circuit galvanic cell that continuously corrodes the electrode material and degrades the electrical characteristics of the microelectrode. Gold-plated tungsten wires, for instance, have been shown to corrode readily in phosphate-buffered saline (Figure 2gh).[209–210] Not only does this negatively impact the electrical properties of the electrode, but it can also lead to toxic metal ion generation.[211] Silver electrodes, for example, have been shown to rapidly oxidize in the body, leading to large implant mass loss and rampant tissue inflammation.[212–214] Corrosion in tissue commonly occurs between two metals, metals of varying purity, or a heterogeneous alloy surface, where one metal dissolves and deposits onto the surface of the other metal through ion migration facilitated by the electrolyte solution.[215] This can be avoided through homogenously alloying multiple metal elements together. Corrosion resistant, higher atomic weight transition metals with good biocompatibility, such as platinum or iridium, are chosen as preferred electrode materials.[21] In addition to improving corrosion resistance, alloys combine the mechanical and electrochemical properties of two metals, allowing for tunable mechanical and electrical properties.[216–219] For example, pure platinum is too soft for use as a cortical penetrating microwire, so it is commonly implemented in an alloy with the stiffer metal iridium, thus resulting in a stiffer, lower impedance electrode.[218–219] Even without metal adhesion layers, some metals can be prone to delamination and corrosion in physiological environments. Platinum black,[220] iridium oxide,[221] and nanoporous materials[222] can all be used to increase the ESA of the probe. However, careful selection of material selection, site size, and deposition parameters are necessary as these coatings are often prone to delamination or electrode dissolution.[207–208, 223] For example, platinum black suffers from low mechanical stability and poor adhesion to the electrode substrate,[224] while iridium oxide films become more prone to degradation and instability during electrical stimulation as electrode site sizes becomes smaller and charge densities increase.[207]

Electrodeposition of CPs can also control corrosion. PEDOT is especially promising due to its stability in oxygen-rich, hydrated environments,[59] since oxidation further polymerizes the CP rather than corroding the metal.[28] Likewise, undoped PPy coatings have been shown to impart corrosion resistance on steel.[225] However, while CP coatings offer electrochemical benefits and a wide array of options for functionalization, they have difficulty maintaining lamination[226] and are brittle.[227] Therefore, when using CP coatings, it is also important to consider the underlying conductor material. Care must be taken to ensure that the CP adheres well to the electrode site material to prevent delamination. Adhesion can also be improved by appropriate dopant selection or by surface premodification such as roughening.[228] For example, addition of self-assembled alkylsilane monolayers improved PPy adhesion.[229] The size of the dopant molecule is an important factor to consider. For example, PEDOT doped with large polystyrene sulfonate (PSS: M.W. 100,000) had an increased tendency to delaminate due to smoother electrode morphology when compared to doping with smaller p-toluenesulfonate (pTS: M.W. 194.18) and perchlorate (ClO4).[230] However, small dopants can leach out of the CP matrix eventually leading to a decrease in conductivity and long-term instability in vivo.[231] On the other hand, large dopants such as PSS (M.W. 70,000)205 typically remain trapped within the CP matrix, and therefore do not contribute to a loss in conductivity.[232] Unsurprisingly, appropriate selection of the conductive polymers (monomers and/or oligomers) used for electrochemical deposition is also critically important for the success of the electrode. Although, PPy is commonly used, due to its ease of growth and low toxicity, PEDOT exhibits superior chemical and electrochemical stability. Coating thickness is also an important consideration, with thicker PEDOT coatings displaying lower impedance measurements on average compared to thinner coatings, but are more prone to delamination.[189] It has been suggested that rough-patterned surfaces offer better adhesion of polymers to the substrate than smooth surfaces.[228, 230, 233] Furthermore, the applied potentials required for electrochemical deposition can cause material dependent corrosion which can disturb the integrity of CP coating, where oxidation of the metal can block electron transfer resulting in a non-uniform, patchy coverage.[234]

The risk of corrosion can also vary depending on whether the electrode is used for stimulation or recording: excessive electrode polarization during stimulation has been shown to produce irreversible electrochemical reactions that can degrade metals (such as stainless steel[235]) which are biologically stable otherwise. This has led to the exploration of conductive polymers and CNT composite materials for recording and electrical stimulation electrode materials.[82, 236–241] CNT doping improves the charge injection capacity through several mechanisms, including increased coating surface area, CNT electrical conductivity, and the additional charge transfer mechanism of small cationic molecules entering the coating to serve as counter-ions against the trapped anionic CNTs when the CP is reduced. These attributes provide the coating with substantial non-faradaic (capacitive) and faradaic character in both oxidized and reduced states.[242] Mechanical stability tests following both acute and chronic stimulation, as well as chronic soaking, revealed PEDOT doped with multi-walled nanotubes (PEDOT/MWNT) and layer-by-layer CNT composites exhibited none of the delamination or cracking that are typical of PEDOT coatings or IrOx sites.[82, 236, 243] Interestingly, PEDOT doped with carboxylic acid functionalized CNT maintained recording quality despite increases in impedance over 3–8 weeks post implant.[244] However, careful consideration of size and concentration are necessary since ejected nanoparticles can cause frustrated phagocytosis, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and membrane lysis.[245–246]

Lastly, the biological response to the implant contributes to electrode failure in a variety of ways. Initially, biofouling, or protein adsorption on the electrode surface, leads to encapsulation, which increases the resistance and capacitance of the electrode, while reducing the electrochemical surface area and attenuating the high frequency content of the electrical stimulus.[232] This is particularly true for high ESA electrode materials where the protein and glial cells restrict ionic diffusion.[247] A study for cardiac pacing electrodes showed that the advantages for having a high ESA electrode were lost 3–8 weeks after implant unless anti-inflammatory steroids were released from the electrode site.[248] Biofouling has also been shown to be exacerbated by stimulating electrodes. For example, IrOx electrode sites used for chronic in vivo stimulation or CV testing demonstrated more biological adhesion compared to non-stimulating electrode sites or sites used only for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.[221] Besides decreasing electrode performance, the tissue response also continuously facilitates the degradation of the insulation and electrode site materials. Cracked or delaminated insulation is further exacerbated by body heat and infiltrating immune cells that produce reactive oxygen species.[5, 249–250] Activated macrophages have been speculated to break down cracked parylene coatings.[99] Efforts towards reducing the biological factors’ contribution to material degradation and recording failure are aimed at reducing biofouling, and improving the stability of the underlying materials. For intracortical electrodes, biofouling can be minimized by modifying the electrode surface properties and minimizing damage to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) upon electrode insertion. Various hydrogel and polymer coatings can be applied to electrode surfaces to increase hydrophilicity or incorporate anti-biofouling molecules or drugs. Common anti-biofouling polymers used in surface functionalization include polyethylene glycol (PEG) and PEG methacrylate (PEGMA). Boron-doped-diamond electrodes have also been shown to exhibit reduced biofouling and more stable electrochemical properties than conventional TiN electrodes.[251–252] Combining anti-biofouling surface chemistries with image guidance technology to avoid tearing major blood vessels during insertion may minimize overall inflammation and glial encapsulation.[33] A combination of materials and design selection will help improve the long-term performance of implantable interfaces.

2.6. Size and Geometry: Surface Area and Diffusion

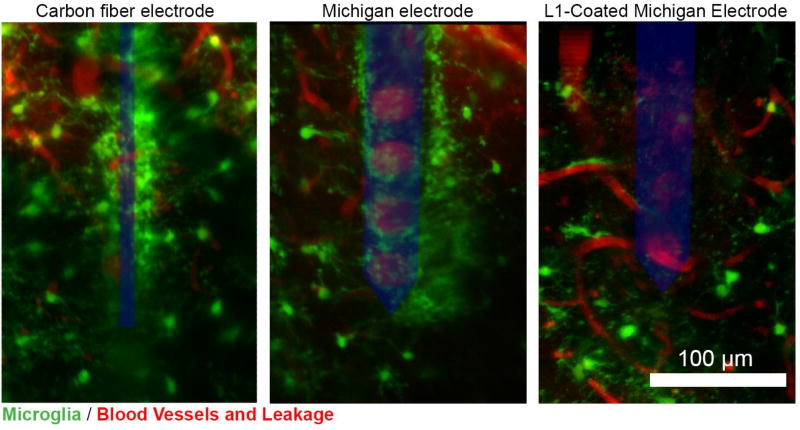

Initially, the size and geometry of implants were believed to play a small role in recording performance and tissue integration when comparing three microelectrode designs with cross-sectional areas ranging from 1,450 – 16,900 µm2.[253] However, in vitro and in vivo studies with polymer fibers show glial attachment significantly decreased when the fiber diameters were less than 12 to 5.9 µm, respectively.[254–255] In the brain, it was shown that 20, 50, and 150 µm2 cross-sectional areas significantly improved neural health and reduced glial encapsulation compared to 3,264 µm2 (Figure 4a–c).[256] Lastly, microelectrodes with 55.4 µm2 cross-sectional area demonstrated significant improvement in chronic single-unit recording performance when compared to traditional devices with a 1,875 µm2 cross-sectional footprint.[128] This has led to a number of hypotheses on how size and geometry may be designed to enhance chronic recording performance.[8, 244] For example, devices with holes or lattice structures might improve recording performance by allowing trophic factors to diffuse from one side of the probe to another, which can potentially improve the health of the tissue around the probe.[8, 244] In addition, tissue can regenerate through the probe holes, which both improve electrical and chemical signaling between the tissues on either side of the probe as well as to prevent probe migration by providing a soft anchor once the tissue heals after the initial insertion injury.[257] These, in turn, have been demonstrated to impact chronic neural recordings and the efficacy of stimulation therapies.[258] Another hypothesis is that these lattice structures reduce the surface area for biofouling,[128] as well as the diffusion barrier for pro-inflammatory cytokines, which cause an accumulation of these cytokines around the probe.[259] Similarly, ECoG arrays also benefit from a more open architecture due to tissue growth through the holes, which minimizes the amount of scarring formed between the electrode sites and the brain.[260–261] Reducing the overall cross-sectional area of the implant reduces the overall volume of the implant. For implantable probes, lower implant volumes reduces the tissue displacement volume that occurs during device implantation, which in turn, decreases the mechanical strain experienced by neighboring neurons (Figure 4de).[8, 34] This strain has been shown to inhibit activity of nearby neurons and cause additional inflammation that negatively impacts the nearby tissue health.[262–263] Finally, the location of the electrode sites on the implantable probe is thought to influence recording characteristics. For instance, electrode sites located at the tip of the probe are hypothesized to have a larger viewing radius (see section 2.7), or volume of tissue in which extracellular action potentials can be detected, compared to sites located along the shank.[117] This results from tissue located behind the implant, or on the opposite side of the shank where the electrode sites are located, is not directly exposed to those sites, but is more exposed to sites located on the tip.

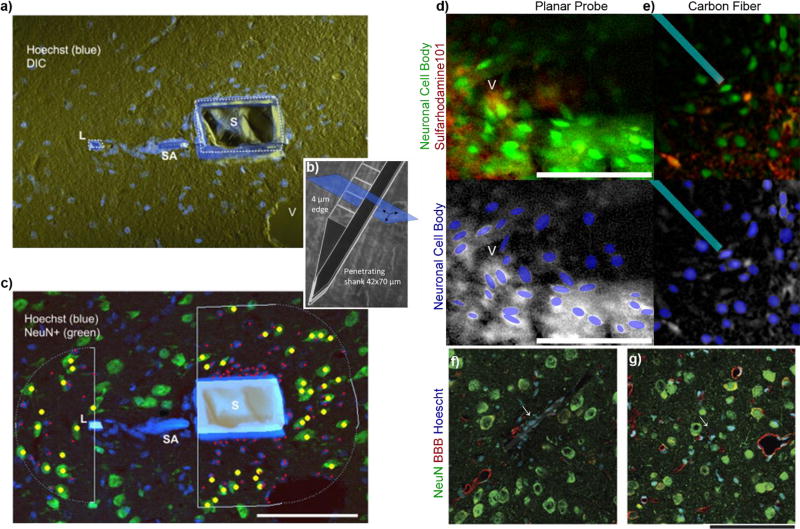

Figure 4. Implant size impacts acute and chronic tissue integration.

a) Tissue around the probe’s (b) thin polymer lattice structure showed significant reduction in encapsulating cells and improved neural density (c). (Adapted with permission from[256, 392]). d–e) Two photon imaging of tissue strain in vivo from a Michigan Electrode Array (d) and carbon fiber microthread electrode (e). Neurons are green, while recording sites and astrocytes are red. Cyan outline highlights microthread electrode. Neurons in panel c are much more compressed and oval/elliptical than neurons in panel d, indicating increased mechanical strain from the embedded electrode volume. Reprinted with permission from[34] Copyright 2014, Elsevier. f–g) Chronic histology shows carbon fiber microthreads with an 8-µm diameter reduced tissue reactivity and improved neuron density of microthread (g) compared to silicon electrodes. Reprinted from[128] Copyright 2012, with permission from Nature Publishing Group.

The benefits of minimizing the volume and cross-sectional area of implants has motivated advances in microscale and nanoscale electrode technology. Wire shank devices with 1–10 µm diameters have been fabricated with silicon, gold, carbon fiber, and conductive polymer composite substrates with excellent electrical properties and minimal host-tissue response.[264–268] On the nano-scale, etching and chemical vapor deposition of silicon has enabled the creation of devices <150nm diameter for in vitro and in vivo applications and using tobacco mosaic virus as a biotemplate has enabled metal wires to be as thin as < 20nm in diameter.[269–275] However, these introduce new challenges,[28] including handling, packaging, resistive heating, and in vivo chronic implantation requirements.[168–169] In addition, decreasing the size of the implant corresponds with a smaller electrode site, which increases impedance. This can be addressed by increasing the ESA:GSA ratio(see section 2.4).[70–71, 186, 251]

Given that FSCV measurements require that neurochemicals of interest either directly adsorb to the electrode surface or diffuse into the vicinity directly adjacent to the electrode, there has been a fundamental push towards the use of FSCV electrodes with diameters of 10 microns or less.[276] The diameter of the carbon fiber electrode is important to decrease local damage to the synaptic end-terminals which are the neurochemical sources, as well as decrease biofouling and/or reactive gliosis which may create a barrier preventing the adsorption/diffusion of neurochemicals to the surface of the electrode.[276] Prior studies have demonstrated in-vitro that biofouling related to protein adsorption to the surface of the electrode can dramatically reduce sensitivity to dopamine and other neurochemicals of interest.[277] As carbon fibers are mechanically brittle, a stringent requirement of the use of carbon fiber FSCV electrodes with diameters 10 microns or less may be problematic in terms of handling and long-term implantation.[278]

There is no published work directly comparing different diameter sizes for FSCV electrodes and neurochemical recording quality in a chronic in-vivo experimental preparation. Nevertheless, difficulties have been observed in obtaining acute dopamine measurements when implanting a 50 micron diameter boron-doped diamond FSCV electrode, likely due to trauma to the adjacent tissue preventing dopamine release locally.[279] However, using a dopamine reuptake inhibitor to promote dopamine diffusion from intact tissue into traumatized tissue did enable dopamine detection with these larger devices.[279] These data support a substantial body of work demonstrating that 1) implantation of a 220 µm diameter dialysis probe can dramatically impact the release and reuptake of neurochemicals at least 220–250 µm from the microdialysis probe,[280–281] 2) tissue near probe tracks created by 280 µm diameter microdialysis probes exhibit ischemia and endothelial cell debris which is most prominent at 4 hours post implant,[282] 3) at 24 hours the microdialysis probe tracks are surrounded by hyperplasic and hypertrophic glial and glia processes,[282] and 4) 7 micron diameter carbon fiber probes produce a diffuse disruption of nanobead labeling, but no focal disruption of blood vessels, evidence of endothelial cell debris, or glial activation.[282] Across all interface modalities, there is increasing evidence that subcellular geometries improve long-term tissue integration.

2.7 Volumetric Density & Channel count

For recording applications, the demand for a greater number of channels has increased. More recording channels allows for a greater volume of tissue to be sampled, and further, multiple channels located closely together allows for the sampling of overlapping volumes of tissue.[147, 283–284] This makes triangulation of the signal across multiple electrodes possible. An important consideration for multi-shank devices is the impact of the overall footprint of the device on the tissue health. More specifically, the volumetric density that the device occupies in the brain over a given amount of space can impact performance. Even if the same volume is implanted into the brain, the maximum strain on the tissue can be reduced by distributing the implant volume over a larger tissue volume as demonstrated by finite element modeling (Figure 5). For example, a single shank tetrode made from four 50 μm diameter electrodes may generate a tissue response similar to a single 100 µm diameter wire, but would generate a very different tissue reaction when compared to four 50 µm diameter wires that are implanted with 1 mm spacing over a large region of the cortex. However, additional considerations may be required based on how the shank spacing impacts injury (tearing and compressing) to the underlying vasculature.

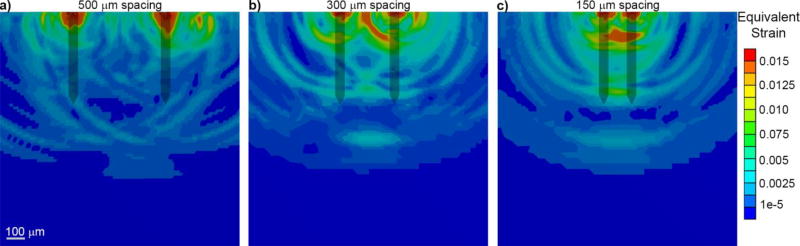

FIGURE 5. Probe insertion results in high strain between shanks of multi-shank devices, with more strain generated between densely packed shanks.

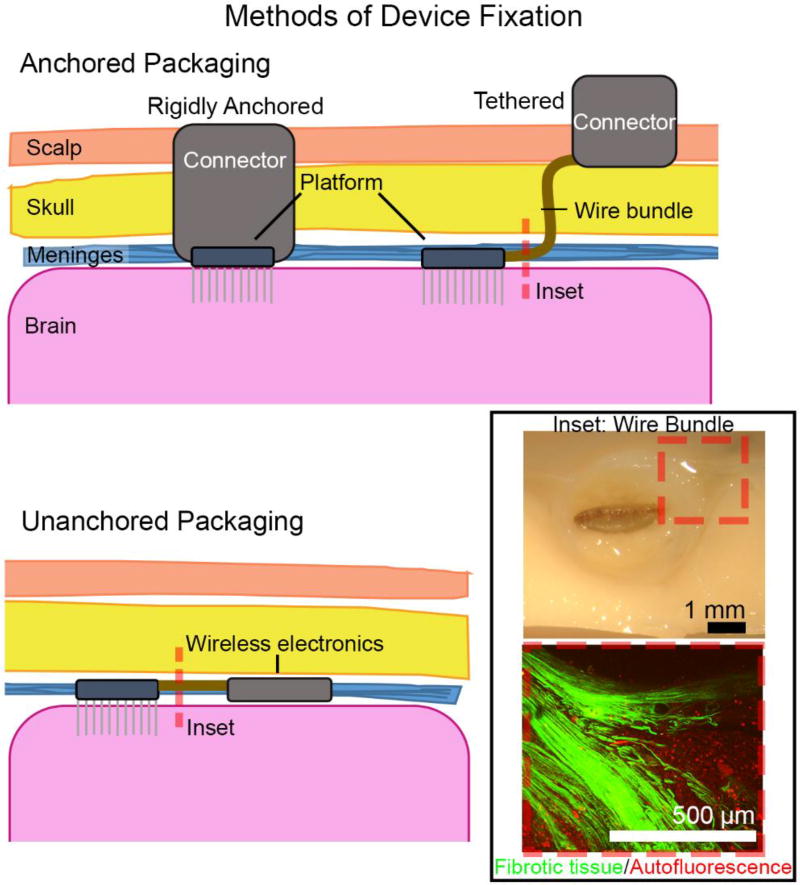

A finite element simulation of Michigan-style planar silicon probe insertion into a visco-elastic brain phantom is shown. The maximum strain value of each element following insertion is displayed. a) When the probe shanks are spread far apart (500 µm tip-to-tip spacing), there is little overlapping strain between shanks. b–c) As tip-to-tip spacing gets tighter, there is increased tissue strain between shanks (300 and 150 µm). Scale bar = 100 microns.

When considering configurations of multiple penetrating shanks, the most important factors are the density of the shanks and the configuration and footprint of the platform piece where the individual shanks come together. With a single shank, it is possible to avoid penetrating surface pial vessels and large penetrating blood vessels,[285] but with multiple, densely-packed shanks, there is a higher probability for vascular injury, microhemorrhage, and exacerbated scarring and cell death, which further increases with greater shank density.[286–289]. Despite this, there are few studies that define a “critical” shank spacing to avoid compounding damage. Both electrophysiological performance and gliosis are progressively worse for Michigan style devices and microwire devices at tip-to-tip spacings < 600 µm, while wire shanks that are 1 mm apart are indistinguishable from solitary electrodes.[290–292] For tapered devices, the base-to-base spacing of shanks should also be considered. The blood supply for the underlying cortex enters through the surface of the brain, and it is possible that the high-strain of narrow base-to-base separation could disrupt that blood flow.[293] Evaluating the effect of shank density on the hemodynamics of the underlying cortex should be examined in future studies.

Common types of multi-shank arrays (silicon planar Michigan arrays, silicon bed-of-needles Utah arrays, and metal microwire arrays) have been compared in 1–4 month-long rodent studies.[294–296] These studies show that metal wire shanks tend to outperform planar or bed-of-needles style silicon devices in chronic electrophysiology with higher SNRs and lower impedances, as well as with less long-term BBB dysfunction. In addition to different materials, these devices vary in shank density, shank shape, and platform area, complicating the interpretation of these results. Future studies should systematically vary these parameters to determine their significance for long-term probe viability.

2.8. Flexibility: Softness/Geometry

Once in the brain, a neural probe spends the rest of its life battling a wet, chemically dynamic, and mechanically tumultuous environment. This mechanical environment is dominated by “micromotions”, which are the movements of the brain in the cavity of the skull in response to respiration, pulsation, and everyday movement.[297] This effect is likely to be greater in larger primates than rodents due to larger and more intricate brains and interstitial space.[298] While the material composition of the probe will largely determine how it fares in the mechanical and chemical milieu of the brain, many groups have also shown that the flexibility of the probe can have an impact on how the host-tissue response and micromotion-related strain is generated by the probe.

Flexible implantable devices are believed to reduce the mechanical strain experienced by tissue due to motion especially in the brain when devices are anchored to the skull. The brain is normally floating inside a cerebrospinal fluid filled dural sac which in turn floats inside of the skull. In humans, the brain and skull are usually separated by about 2–4 mm while this number is closer to 100 µm in mice.[35] As such, large forceful movements or impacts to the skull can lead to substantial brain tissue displacement and mechanical strain to the tissue surrounding rigid implants. In addition, there are smaller micromotions and physiological motions in the brain due to respiration and heart-related blood flow pulsation.[299–300] These small movements can increase when craniotomies and duratomies are left open and unsealed.[301] Finite element modeling studies have shown that stiff or rigid devices that are anchored to the skull resist complying with these brain movements.[302–303] In turn, this can lead to a perpetual generation of mechanical strain and pro-inflammatory cytokines or even reinjure the tissue resulting in device failure.[5, 8, 34, 304] As such, there has been increased focus on developing implantable technologies that are much more compliant, which can be achieved in several ways:

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

where kc is compliance, l is the device length, A is the cross-sectional area, E is the elastic modulus (or Young’s modulus), w is the width of a planar devices, t is the thickness of a planar devices, do is the outer diameter of a cylindrical devices, di is the inner diameter of a cylindrical devices, and k is stiffness. The compliance of a device can be improved by employing materials with a low elastic modulus, reducing the cross-sectional area of the device, or increasing the length of the device. In order to reduce the rigidity of neural implants from silicon backbone substrates and large metal backbones (100’s GPa), engineers have turned to polymers and thin-film technology.[305–306] Polymers can have softer material properties (Young’s modulus), low thermal expansion, exceptional solvent tolerance, and good dielectric constants. However, polymers can also have high water absorption, poor solvent tolerance, and changing dielectric properties that increase when it has absorbed water or ions, which negatively impacts the chronic performance of implanted devices. Therefore, polymers selected for device design must satisfy these broad range of criteria.

Hydrogels are among the few materials that can be engineered to have similar mechanical properties to brain tissue due to their high water content.[307–309] Microglia have been shown to be responsive to the stiffness of a material, migrating from softer to stiffer surfaces.[310] However, hydrogels lack many of the other material properties necessary for functional performance, such as electrical, strength, and durability properties. Furthermore, the swelling of hydrogel materials can lead to additional neural cell death if the hydrophilicity, crosslink density, and weight of the polymer is not properly optimized.[311–312] This greatly limits the ability to construct functional devices from low elastic modulus hydrogels.

Reducing the cross-sectional area of the probe track has shown significant improvement in chronic neural recording performance, but as the dimensions decrease, other challenges emerge such as the mechanical handing requirement related to insertion and durability.[71] Similarly, overall increases in device length lead to new challenges. For specific anatomical targets, length can be increased by entering the tissue at a very distant region, though this substantially increases tissue injury. Alternatively, a meandering design, such as a sinusoid, could be employed to increase the length of the device without dramatically increasing the implantation related injury.[313–316] The placement of trifilar coils along the lead combined with strategic anchor points to prevent migration, such as with suture pads, may improve device performance, similarly to pacemakers.