Abstract

Purpose

To explore vitreoretinal pathologies and their longitudinal changes visible on handheld optical coherence tomography (HHOCT) of young children with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR).

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed HHOCT images for vitreoretinal interface and retinal abnormalities, and optic nerve head (ONH) elevation.

Results

From 26 eyes of 16 children (mean age 32 months) with FEVR, ten had ONH dragging on photographs and in these HHOCT revealed: temporal and anterior retinal displacement, prominent vitreopapillary adhesion or traction, and retinal nerve fiber layer thickening at ONH margins with adjacent retinal elevation. Despite nearly normal photographic appearance, HHOCT revealed ONH elevation with vitreopapillary traction (6/16 eyes), ONH edema (1/16 eye) and retinal vascular protrusion (5/16 eyes). HHOCT-visualized vitreous abnormalities (18/26 eyes) were more prevalent at higher stages of disease. HHOCT-visualized elevation of ONH and retina worsened over time in 9 eyes and improved in 5/6 eyes after vitrectomy.

Conclusions

HHOCT can detect early ONH, retinal and vitreous changes in eyes with FEVR. Contraction of strongly adherent vitreous in young FEVR patients appears to cause characteristic ONH dragging and tractional complications without partial PVD. Vitreopapillary dragging may be visible only on OCT and may progress in absence of obvious retinal change on conventional examination.

Keywords: FEVR, optic nerve, retina, children, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, sdoct, oct

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) is a rare hereditary disorder principally affecting retinal angiogenesis. Incomplete peripheral retinal vascularization results in ischemia and subsequent complications such as retinal neovascularization, exudation, vascular dragging, retinal fold and retinal detachment.1–4 Although it may progress at any age with sight-threatening manifestations, visually significant FEVR most often presents in childhood, but many patients with stage 1 – 3 remain undiagnosed. Conventional staging of FEVR has been based on evidence of vascularized retina, neovascularization, exudation and detachment: with stage 1 notable for the avascular periphery; stage 2, avascular periphery with neovascularization; stage 3, macula-sparing retinal detachment; stage 4, macula-involving retinal detachment; stage 5, complete retinal detachment, and A versus B designation for absence versus presence of exudate.4,5

While some children may be born with very advanced disease and detachment, in many children, early in the disease or in mild cases, the peripheral avascular area or retinal neovascularization is often very difficult to find when peripheral angiography is not performed. This lack of further evaluation may occur because of the lack of any symptoms and unremarkable posterior retinal appearance which may include a lack of exudation.5 Subtle abnormalities which are often hardly noticeable in the posterior pole, include an increased distance from the fovea to the disc, more radiating and straightened retinal vessels extending from the optic nerve head (ONH) and smaller than normal ONH size.6–8 Although the primary pathology in FEVR is located in the periphery, its harmful effect on visual function typically arises through the effects on the macula and optic nerve.

The vitreous gel is recognized as having an important role during the progression of FEVR. The vitreous is especially adherent to the retinal surface in young children.9 Moreover, pathologically adherent and contractile posterior hyaloid in FEVR causes various forms of the tractional complications, such as posterior hyaloid organization, vitreomacular traction, and vitreopapillary traction.10 While fundus examination, fluorescein angiography and ultrasound have been used for assessment across all ages, optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been shown to be a valuable tool in monitoring the extent of vitreoretinal interface disease and progression only in older children and adults.10–12

We hypothesize that OCT could help detect similar abnormal findings at the posterior pole in earlier stages of FEVR in infants and young children. However, obtaining OCT images in younger patients can be difficult due to their inability to cooperate; thus in the two studies to-date, of OCT imaging in FEVR, clinical tabletop systems were used for imaging, and the mean ages were 19 years and 10 years.10,11 With the advent of handheld OCT (HHOCT), it has become possible to image with OCT during the examination under anesthesia without “flying baby” positioning13, and to find retinal, vitreous and ONH abnormalities in pediatric patients who are not cooperative enough to be examined using standard OCT systems in the clinic.14,15 This has enabled clinicians to observe how such abnormalities change over time or after treatment even in very young children.

The aim of this study was to explore the range of vitreoretinal pathologies visible on HHOCT images in young FEVR patients. Also, we investigated those changes during the follow-up period as the disease evolved.

Methods

This study is a single-center, retrospective case series of patients with a clinical diagnosis of FEVR who were enrolled in an observational HHOCT imaging study at Duke Eye Center during a 7-year period from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2015. The study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and all tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. A parent of each subject provided informed consent for the study which included research imaging as well as analysis of medical records. Eligible participants were identified by review of the research database and medical records based on clinical findings, family history, and genetic testing when available. Note that infants and children with severe disease, with anterior ocular opacities, total retinal detachment or vitreous hemorrhage in both eyes, which precluded imaging, were not enrolled in the OCT imaging study. If one eye had these findings, it was excluded from analysis.

All infants and children with FEVR had been imaged during examination under anesthesia, with funduscopic photographs and fluorescein angiography obtained using the RetCam II Wide-Field Digital Imaging System (Clarity Medical Systems Inc., Pleasanton, CA) with the 130° widefield D1300 lens. All HHOCT images were obtained with the portable handheld spectral domain OCT system centered at 840-nm wavelength (Envisu 2200/2300 Bioptigen Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC) as described by Maldonado and colleagues.16 Early in the study this was an investigational device which is comparable to the now FDA-cleared Envisu system. In each HHOCT session, volume scans in the macula, ONH and extramacular area as peripheral as was possible were obtained under 8mm×8mm, 10mm×10mm and/or 16mm×16mm scan length setting. Linear scans that included the fovea were also performed.

Data collection included demographics such as birth history, FEVR staging at first examination, highest FEVR staging, laser and surgical treatment history, visual acuity, genetic testing results, and total number of imaging sessions. All imaging sessions were reviewed. Staging was determined as previously described4, based on the combination of clinical examination, fundus photographs and fluorescein angiogram.

HHOCT images were considered acceptable for analysis if the series of scans were appropriately focused and aligned, of sufficient signal strength to confidently identify the anatomical landmarks of the nerve, and covered the optic nerve from edge to edge both horizontally and vertically. The edge of the optic nerve was defined as the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) border. HHOCT images were converted into Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format and qualitatively graded in OsiriX medical imaging software (OsiriX Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland). 3D image processing of volumetric OCT data was performed by using custom MATLAB scripts and an enhanced rendering pipeline that included volumetric filtering, edge enhancement, feature enhancement, depth based shading, and phong lighting.17

HHOCT images were analyzed for retinal folds, vitreoretinal interface, preretinal, intraretinal, subretinal abnormalities and ONH elevation on the basis of image interpretations through systematic review by 1 author (J.L.) with secondary review of all images by C.A.T. and all optic nerve images by M.A.E. The volume scans with the best image quality were selected for each subject, with at least one ONH and macular volume scan for each eye.

ONH elevation was defined as elevation of the anterior surface of the ONH above the level of the surrounding retinal nerve fiber layer.14 This could occur with or without loss of cup. All the images were reviewed by two independent observers (J.L. and M.A.E.), and another observer (C.A.T.) arbitrated the evaluation.

Results

Nineteen patients with FEVR were identified during the study period. Of those 38 eyes, OCT imaging was not performed on one eye each of two patients due to the presence of corneal opacity or phthisis. Ten eyes had imaging attempted and were excluded from this study analysis due to insufficient OCT image quality caused by total retinal detachment or media opacities. Therefore, 26 eyes from 16 patients had OCT images of good quality for interpretation and assessment of macula, ONH and vitreoretinal interface in this study. Patient demographics and clinical findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical findings of included patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR)

| Features | No |

|---|---|

| Age (n=16 patients) | |

| Mean (Median) | 32 months (27months) |

| Range | 2 months – 10 years |

| Sex | |

| Male | 12 |

| Female | 4 |

| Race | |

| White | 9 |

| Black | 5 |

| Hispanic | 1 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Eye imaged (n=26) | |

| Right | 14 |

| Left | 12 |

| FEVR staging at first examination | |

| Stage 1 | 4 |

| Stage 2 (A, B)* | 13 (11, 2) |

| Stage 3 (A, B)* | 5 (3, 2) |

| Stage 4 (A, B)* | 4 (2, 2) |

| Previous treatment | |

| None | 16 |

| Laser photocoagulation | 9 |

| Incisional surgery | 1 |

A: without exudate, B: with exudate

Macula at first examination

Nineteen of 26 eyes had a normal foveal depression on OCT, although two of these 19 eyes had persistent inner retinal layers (FEVR stage 2A and 3B) and three of the 26 eyes had a flat foveal area associated with retinal stretching (FEVR stage 3A, 3A with previous laser, and 4A). Two of the 26 eyes (all with FEVR stage 4A) had foveal elevation associated with vitreomacular traction. The final two of 26 eyes had premacular hard exudates18 and foveal thickening with an updrawn fovea in one eye and appearance of likely small cystoid spaces (the inner surface exudates limited the view to the outer layers) there was late fluorescein leakage in the macula of the eye with the updrawn, thickened fovea and both eyes had FEVR stage 2B with previous laser) Seventeen of 19 eyes with normal foveal contour had an intact central ellipsoid zone; 2/19 eyes had a faint and disrupted ellipsoid zone. In 7 eyes with an abnormal foveal contour, the ellipsoid zone could not be evaluated. Mean subfoveal choroidal thickness was 281.45 ± 76.90μm. (284.79 ± 71.74 μm in eyes with normal contour vs 270.2 ± 103.10 μm in eyes with abnormal contour) Mean subfoveal thickness was 331.89 ± 95.67μm in the 9 eyes with laser treatment versus 257.14 ± 57.02μm in the 16 eyes without laser treatment.

ONH at first examination

ONH findings on fundus photographs

16/26 eyes had a nearly normal appearance of the posterior fundus and ONH (one of which had prepapillary vitreous opacification) (Figure 4) without dragging of vessels and with no visible abnormality of the optic nerve head. Two of 26 eyes had subtle ONH dragging (Figure 1A) which was accompanied by very mild dragging of vessels and 8/26 eyes had obvious ONH dragging (Figure 1B, 1C, 1D, 1E). 7/8 eyes with obvious ONH dragging had vascular dragging, which was defined as definite straightening of retinal vessels with or without vascular engorgement and narrowing of the angle between the temporal arcades. All 9 eyes at FEVR stage 3 or 4 had ONH dragging, while one out of 13 eyes at stage 2 had ONH dragging.

Figure 4.

Diagram: The multiple causes of optic nerve head (ONH) elevation at baseline in the eyes of young children with FEVR. Optical coherence tomographic images of ONH elevation due to focal vitreopapillary traction (A), ONH edema (B) and retinal vascular protrusion (C).

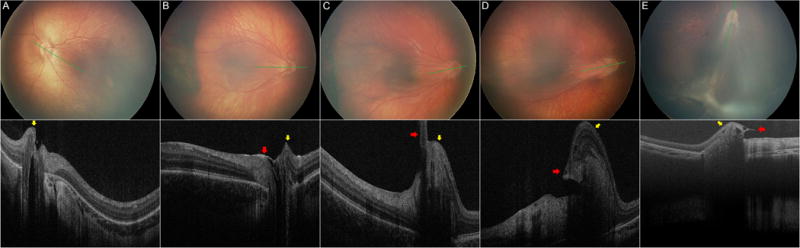

Figure 1.

Fundus photographs (upper) and corresponding optical coherence tomograms (lower) in five representative eyes of young children with FEVR and with optic nerve head dragging. From left to right the vitreopapillary dragging is possible (A) to a severe case with radial retinal fold (E). There is displacement of neurosensory retina (yellow arrows) toward the lesion side (mainly temporally) and upward. Note the evidence of strong vitreopapillary adhesion: focal posterior hyaloid thickening at temporal disc margin (B, red arrow) or vitreopapillary traction as evidenced by thick vitreous band at the leading edge of displaced retina (C–E, red arrows). In contrast, (A) had prior pars plana vitrectomy and showed no such attachment. Vitreopapillary adhesion is also observed in figure 2B.

ONH findings on OCT

In the 16 eyes with a nearly normal posterior fundus appearance on clinical examination and on fundus photographs, four eyes looked normal and 12 had ONH elevation (Figure 4) on OCT images. OCT findings in the eyes with ONH elevation included: 6 eyes with vitreopapillary traction or prepapillary membrane, 1 eye with mild ONH edema which was confirmed by leakage in fluorescein angiography, and 5 eyes with protrusion of the retinal vessels at the ONH (Figure 4). All 10 eyes with obvious or subtle ONH dragging on fundus photography had the following findings from OCT images:

Neurosensory retinal displacement: A displacement (or shifting) of the peripapillary neurosensory retina toward the peripheral fibrovascular lesion side. Because with OCT we could view both lateral and axial changes, we commonly observed that the peripapillary nasal retina was shifted temporally over the ONH and upward (towards the vitreous) at the ONH (Figure 1).

Retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickening at the temporal, superior and inferior disc margins, along with absence of outer retinal layers in the temporal peripapillary area above Bruch’s membrane leaving only RNFL at the temporal margin of the ONH (Figure 2).

Retinal elevation along the vasculature extending away from the optic nerve and on the side towards the peripheral pathology. The elevation was greatest at the area closer to the ONH and lowered as it extended farther away from the ONH (Figure 3). Retinal vessels were seen at the apices of these two elevations (Figures 3B, 3C, 3D). The retinal elevation was confined to the area around ONH in 6 eyes (Figure 1A, 1B, 1C) and extended beyond the posterior pole area but did not connect to the periphery in two eyes (Figure 1D). In one eye, the retinal elevation was connected with a peripheral fold to form a radial retinal fold (Figure 1E).

Strong vitreopapillary adhesion based on focal posterior hyaloid thickening at the temporal disc margin (Figure 1B, 2B) or visible vitreopapillary traction on OCT as evidenced by a thick vitreous band at the leading edge of displaced retina (Figure 1C, 1D, 1E), except in one eye which already underwent pars plana vitrectomy before the first imaging session.

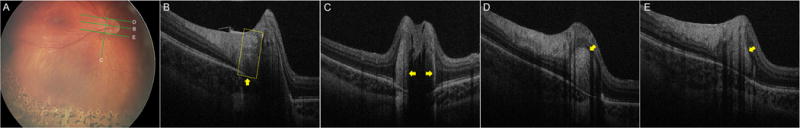

Figure 2.

HHOCT images of retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickening (arrows) at the temporal (B, C), superior (D) and inferior (E) optic nerve head margins of a young child with FEVR. Near the temporal margin of the disc (B, box area), there is only nerve fiber layer overlying Bruch’s membrane. Those RNFL thickenings are not actual swelling but but it appears that deeper parts of optic nerve have been drawn upward by the traction. This thickening is also visible in figure 1A and figure 1B.

Figure 3.

Optical coherence tomography showing retinal elevation around the optic nerve head (ONH) in eyes with ONH dragging (A–D) in young children with FEVR. The retinal thickness map (E) and 3D reconstructed image (F) show that retinal elevation is highest at ONH area and becomes lower as it extended farther away from the ONH (arrows). Note that retinal thickening is mainly due to the thickening of the nerve fiber layer, and that the large retinal vessels of the arcades, as evidenced by focal posterior shadowing, are present at the peak of and extending along the retinal elevation.

In order to avoid confusion between these OCT-determined findings of vitreopapillary dragging, and with ONH dragging seen on fundus photography, we use the term OCT-vitreopapillary dragging (OCT-VPD).

Vitreous abnormalities on OCT at first examination

Eighteen out of 26 eyes (69%) had at least one of the following vitreous abnormalities: prominent vitreopapillary traction, prepapillary membrane, premacular or preretinal exudates, visible vitreomacular traction or various forms of extramacular posterior hyaloid abnormalities. Extramacular posterior hyaloid abnormalities included vitreoretinal traction, focal vitreous condensation, coarse posterior hyaloid face or membrane like thickening of the posterior hyaloid face (Figure 5). Vitreous abnormalities were more prevalent in higher stages of FEVR, with 0/4 eyes in stage 1, 7/11 eyes in stage 2, and 11/11 eyes in stages 3 or 4. Excluding one eye that previously underwent vitrectomy, posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) could not be seen on OCT in 24/25 eyes, but was found focally in one eye of a child (age 3.5 years, Figure 5H), which had membrane-like posterior hyaloid thickening with focal vitreous separation only at the thickened area.

Figure 5.

Optical coherence tomography of various vitreous abnormalities found in young children with FEVR; vitreomacular traction with premacular hard exudate (A), vitreofoveal traction (B), vitreomacular traction (C), preretinal hard exudate with vitreous condensation (D), preretinal vitreous organization and vitreoretinal traction (E), preretinal focal vitreous condensation (F), hyperreflective, coarse posterior hyaloid face (G), sheet-like thickening of posterior hyaloid face with focal vitreous separation (H). Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy stages were 2 (A, B, D–G), 3 (H) and 4 (C) respectively. Note that there is no posterior vitreous detachment except in one case (H). Even in the case of vitreomacular traction, the vitreous is still attached around the area of tractional elevation (C, arrows).

Longitudinal changes

Four eyes (all stage 1) received no treatment, and 22 eyes had laser photocoagulation as follows: previous laser treatment in 9 eyes, previous laser treatment during incisional surgery in 1 eye and the first laser treatment at the time of the first examination with HHOCT in 12 eyes. Six eyes underwent pars plana vitrectomy; 1 eye at the first examination and 5 eyes during follow up. Twenty-one eyes had more than one OCT imaging session more than 1 month apart, with from 1 to 8 sessions during 1–72 months of follow-up (mean 23 months).

Over time, eight eyes had ONH changes on OCT consistent with a progressive increase in vitreopapillary traction (Table 2, Figure 6). Two eyes developed new onset of OCT-VPD. One eye (#6, FEVR stage 2B) that demonstrated slight vitreopapillary traction at baseline (Figure 6D left) developed OCT-VPD 14 months later, at which time slightly engorged retinal vessels were visible in fundus photographs; this eye progressed two years later to FEVR stage 3B with more severe OCT-VPD (Figure 6D right). Another eye (#10, Figure 6B, stage 2A) developed OCT-VPD 1 month after the baseline examination, without any abnormal funduscopic finding or change; OCT-VPD and FEVR stage did not change during 4 years of follow-up. In addition, two eyes of two children had progression of OCT-VPD parallelling changes on fundus photographs: one eye (#17, Figure 6C) had progression of OCT-VPD with progression of ONH dragging on fundus photography, while the other eye had worsening of optic disc edema in one eye (#5, Figure 6A) and prominent ONH changes on fundus photographs. The four remaining eyes demonstrated some progression of OCT-VPD while funduscopic changes were not visible. All eight eyes had received peripheral laser treatment before (#2, 5, 6, 10) or at the time of first OCT imaging (#15, 17, 18, 21).

Table 2.

Time interval and optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings versus changes visible on fundus examination and color photography in 8 eyes with longitudinal optic nerve head (ONH) change.

| Eye number | Time interval (months) | OCT findings | Changes visible on fundus examination and photographs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes over, in and around the optic nerve | Extramacular vitreous abnormalities | Macular changes | |||

| 2 | 30 | Thickening of prepapillary membrane | Vitreoretinal traction, focal vitreous condensation | – | – |

| 5 | 6 | Worsening of ONH edema and elevation | Vitreoretinal traction, preretinal hard exudate, vitreous condensation | Worsening of premacular exudate | Worsening of ONH edema |

| 6 | 6 | Worsening of vitreopapillary traction | Preretinal hard exudate, vitreous condensation | Worsening of premacular exudate | Engorged retinal vessels |

| 14 | Development of OCT-VPD* | ||||

| 10 | 1 | Development of prepapillary membrane, development of OCT-VPD* | Coarse posterior hyaloid face | – | – |

| 15 | 2 | Development of vitreopapillary traction | Focal vitreous condensation | – | – |

| 17 | 2 | Progression of OCT-VPD* | Coarse posterior hyaloid face | – | Progression of ONH dragging |

| 18 | 2 | Development of prepapillary membrane, loss of disc cupping | Vitreoretinal traction | – | – |

| 21 | 1 | Thickening of Prepapillary membrane | Focal vitreous condensation, vitreoretinal traction | – | – |

OCT-VPD: optical coherence tomography-vitreopapillary dragging

Figure 6.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) and 3D reconstructed images of eyes of young children with FEVR representing longitudinal optic nerve head (ONH) changes in each row A to E. The numbers at the lower left corner of each image represent the age of patients in months. A: worsening of ONH edema with premacular hard exudate, B: development of optical coherence tomography-vitreopapillary dragging (OCT-VPD) with prepapillary membrane, C: Serial images of progressing OCT-VPD over 7 months, note progressive temporal and upward movement of nasal neurosensory retina over the ONH, D: development of OCT-VPD with worsening of vitreopapillary traction, E: development of prepapillary membrane with loss of disc cupping. The corresponding eye numbers are #5 (A), #6 (D), #10 (B), #17 (C), and #18 (E) respectively.

Abnormal macular findings on OCT also developed or worsened over time in three eyes. In one eye (#9), in 3.5 months of follow up, macular thickening developed with apparent contraction of the posterior hyaloid (cellular proliferation into the vitreous may have also contributed) and without any change in optic nerve head. Two eyes (#5 and #6) had worsening of vitreomacular traction in 18 and 22 months of follow-up respectively, and in one eye the ONH edema worsened while the other eye developed OCT-VPD. All of these eyes had one or more accompanying vitreous abnormalities that were described earlier.

Changes on OCT after pars plana vitrectomy

One eye underwent pars plana vitrectomy before the first examination (Figure 1A). Six eyes underwent pars plana vitrectomy for tractional retinal detachment (2/6 eyes), traction/rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (1/6 eye), vitreomacular traction or macular puckering (3/6 eyes). Good anatomic restoration of the macula was accomplished after relieving the vitreomacular traction or removing epiretinal membrane in all 3 eyes. Although the ONH elevation and peripapillary retinal elevation improved in 5 of 6 eyes, the contour of the ONH did not return to normal in any eye (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Longitudinal changes after vitreoretinal surgery to remove membranes and release traction in the eyes of young children with FEVR.

A: OCT in a patient who had vitreomacular traction with loss of normal foveal contour (visual acuity (VA) 20/100) and optic nerve head (ONH) elevation due to ONH dragging. Eight months after the operation, foveal depression and ellipsoid zone were almost restored, and peripapillary retinal elevation persisted despite of improvement and VA was 20/70. B: OCT in a patient who developed a macular pucker during follow up period (VA 20/80). There was ONH dragging with retinal elevation around ONH. Three years after the pars plana vitrectomy, normal foveal configuration and ellipsoid zone were restored but there was still irregular retinal nerve fiber layer thickening and VA was 20/30.

Genetic testing and visual function

Genetic testing for some of the known genetic defects associated with FEVR was performed on 9/16 patients. Wnt-signaling pathway mutations were detected in 5 patients (7 eyes): 3 patients (5 eyes) with NDP mutation (stage 2A, 2A, 3B, 4A, and 4B respectively), 1 patient (1 eye) with FZD4 mutation (stage 4A), 1 patient (1 eye) with CTNNB1 mutation (stage 2A). Among these seven eyes, four eyes had ONH dragging on fundus photography and OCT-VPD. Due to small sample size we could not correlate genetic mutation with OCT abnormalities.

Visual acuity ranged from no light perception to 20/20. The age at first examination of 7 patients (10 eyes) was below 12 months and visual acuities of those eyes were recorded as “fix and follow” or “wince to light”. The number of remaining eyes with Snellen or Teller visual acuity was so small that we could not correlate visual acuity with FEVR stage, OCT findings, or disease progression.

Discussion

This is the first report of longitudinal changes of the ONH and macula as imaged with HHOCT in infants and young children with FEVR. (PubMed search for terms familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, optical coherence tomography and we examined all identified manuscripts for inclusion of children and longitudinal study, date of search:Aug-2-2016) In our series, the mean age at the first HHOCT imaging was 32 months (range 2 months-10 years), with 15 of 16 children (94%) under the age of 5 years. This is much younger than in previous publications.10,11 (mean, age range: 19, 2.4–57 years and 9.8 years, 4 months–23.8 years)

We demonstrate the utility of identifying posterior pole OCT characteristics of FEVR early in life, noting that both presentation and progression of ONH changes were often visible only on the OCT imaging. Children who present with FEVR in the first 3 years of life have a worse prognosis, often due to the severity of disease at onset.19 Nevertheless, in many of those cases, early detection, diagnosis and treatment of FEVR is expected to result in a better visual prognosis.20 The OCT images obtained in older children or adults likely reflect the retinal status of either milder phenotypic FEVR or that of already advanced stages of FEVR.

“ONH dragging”, “optic disc dragging” or “dragged disc” is a clinical funduscopic term, which describes the condition where retinal elements over and around the optic disc are laterally displaced. The dragging is associated with retinal traction exerted by a fibrovascular scar and is accompanied by ectopic macula, displacement of abnormal, tortuous retinal vessels and sometimes by a retinal fold or a retinal detachment.21 Various vitreoretinal conditions, such as idiopathic congenital retinal folds, Wagner syndrome, FEVR or retinopathy of prematurity, can present with ONH dragging which represents advanced or cicatrical stage with irreversible anatomical change in most situations.21–24 We demonstrate clinically valuable characteristic OCT changes associated with ONH dragging (predominantly towards the temporal retina in these eyes with FEVR) and define the unique aspects of ONH dragging on OCT (termed OCT-VPD). The characteristics of OCT-VPD which may not always be evident on clinical or photographic examination include: neurosensory retinal displacement, RNFL thickening arcing temporally around the optic nerve, retinal elevation along the vasculature extending away from the optic nerve and strong vitreopapillary adhesion or traction. Using these combined OCT features, we were able to identify OCT-VPD that was not readily visible on fundus photography.

Neurosensory retinal movement, or retinal movement toward the lesion side, has been reported on OCT11 in eyes with FEVR and retinal folds. The peripheral avascularity reported in FEVR is most severe at the temporal periphery, where neovascularization and fibrovascular proliferation is most prominent, and that’s the reason why retinal movement and ONH dragging are mostly temporally-directed in this disease.2,4,25 However, when the lesion is shifted superiorly or inferiorly, the direction of the retinal fold can vary accordingly (Figure 1E). We also noted, that on OCT imaging, anterior retinal displacement was better ascertained than from the fundus examination or photographs.

The RNFL thickening is comparable to the NFL bundle reported in a case series of eyes with severe dragging and retinal folds.11 We demonstrate thick hyperreflectivity of the RNFL at the temporal, superior and inferior margin of ONH. We believe that this is not due to actual swelling but rather an updrawing of deeper parts of the optic nerve. Had there not been an upward pull of optic nerve, one would expect thinning of the peripapillary RNFL rather than thickening, because of the retinal stretching usually seen in FEVR. Unlike in highly myopic eyes where dragged RNFL was reported over the peripapillary atrophic RPE (temporal crescent)26, in our series, the RPE/Bruch’s complex is intact at the temporal margin of disc suggesting that dragging occurred only at the level of the retina and not of the choroid and sclera.

Retinal elevations along vasculature extending from the ONH are due to thickening of the RNFL and in part to vascular dragging and vitreous traction along the major vessels. These elevations may occur both nasal and temporal to the ONH. In several of our examples, these diminish in elevation with increasing distance from the ONH and thus do not appear to be due to traction from the periphery.

We found that ONH elevation is extremely common in the eyes of young children with FEVR, despite a normal photographic appearance of the ONH (12/16 eyes, Figure 4). We recognize that ONH elevation is not a specific finding in FEVR alone; however, the presence of ONH elevatoin may raise suspicion even when posterior pole fundus photography appears normal. In mild FEVR, peripheral avascular area or retinal neovascularization can be very difficult to find with conventional examination. Fluorescein angiography is often not performed because of the lack of symptoms and because of an unremarkable posterior retinal appearance.5,27 Among these 12 eyes with ONH elevation, five were due to pronounced retinal vascular protrusions in the early stages of FEVR (4 eyes in stage 1 and 1 eye in stage 2). There can be several possible explanations for this. First, it has been reported that patients with FEVR have more retinal vessels radiating from the optic disc in the posterior pole.7,8 Second, the optic disc in FEVR have been found to be smaller than in normal eyes.6,7 When combining these findings, subtle vascular engorgement due to vascular crowding and/or RNFL crowding from a small optic disc may cause optic disc elevations even in these mild FEVR eyes. Third, although not evident on our OCT images, retinal vascular protrusion may be also be related to occult vitreopapillary traction.

Yonekawa et al. already mentioned that tractional membranes in FEVR are not the typical epiretinal membranes seen after PVD, and that they originate from abnormal vitreous that becomes pathologic as the cicatrical disease progresses.10 They recommended the term “posterior hyaloid organization/contraction”. Joshi et al pointed out that the development of cellular infiltration into the attached posterior hyaloid is associated with hyaloid contracture in children with vitreoretinal traction, in contrast to adults in whom proliferation occurs on the inner retinal surface commonly after the vitreous separation.9 Our OCT findings strongly support those opinions. Vitreous was attached to the retinal surface in all young FEVR eyes in this study with the exception of only one eye of one child (age 3.5 years) that had two small areas of focal separation of posterior vitreous. Partial PVD did not occur even during the progression or development of OCT-VPD in FEVR in this study. This OCT finding implies that the vitreous attachment to the ONH and retina is very strong and the vitreous is able to exert a tractional force strong enough to cause ONH dragging and elevation in FEVR. The vitreous is especially adherent to the retinal surface in young children and it is virtually impossible to mechanically detach the posterior cortical vitreous from the retina9, 29; thus in many young pediatric vitreoretinal conditions, vitreoretinal traction may be present without visible separation of the posterior hyaloid from the retinal surface.9, 30–32 It is known that while progression in adults is uncommon, FEVR is more severe and the prognosis is more guarded in younger children, particularly under age 3 years; with macular ectopia, retinal detachments, and retinal folds being the main cause of reduced vision.19, 33 The difference in vitreoretinal adhesion may explain these differences in clinical features between infants and adults in FEVR.

Our OCT findings support the important role of the vitreous in the pathogenesis of FEVR in infants and young children. First, OCT imaging shows that the vitreous is involved in upward ONH dragging in eyes with visible retinal vessel dragging. The vector of retinal movements in eyes with ONH dragging can be divided into two components (Figure 1). One component is toward the preretinal neovascularization, both tangentially along the retina and the retinal vasculature and circumferentially in the periphery. These movements towards the site of the preretinal neovascularization are thought to result from contraction of the peripheral fibrovascular tissue21, in the conventional concept regarding ONH dragging, retinal dragging and radial retinal fold formation. The second component is upward, into the vitreous in an anteroposterior direction and most likely from vitreous traction, which is more readily apparent on OCT. The latter component is much more difficult to characterize with the en face viewing of the retinal surface with fundus photography or indirect ophthalmoscopy, even with stereo viewing. Second, OCT images show that strong vitreous traction alone can result in ONH dragging, in some cases even without retinal dragging by peripheral fibrovascular proliferation. Among 12 eyes with OCT-VPD in FEVR (10 eyes at first examination and 2 eyes in which this subsequently developed), there was no obvious retinal vascular dragging on fundus photography in five of the eyes (one eye with obvious ONH dragging, two possible eyes and 2 later-developed eyes). Third, the pattern of retinal elevation on OCT supports the role of vitreo-papillary traction: retinal elevation is highest at optic disc and decreases as it extends to the periphery (Figure 3) and it runs along the retinal vessels. Vitreous adhesion is strongest at optic disc and along the major retinal vessels.34 Fourth, various forms of vitreous abnormalities were found: in our study, higher stages of FEVR are associated with a higher prevalence of these vitreous abnormalities, and all 8 eyes with longitudinal optic disc changes as well as all 3 eyes with longitudinal macular changes had extramacular vitreous abnormalities. Fifth, there are additional longitudinal optic disc changes that are likely due to vitreous traction: prepapillary membrane in the absence of PVD is actually a part of posterior vitreous, so thickening of prepapillary membrane (Figure 6B), vitreopapillary adhesion with focal vitreous condensation (Figure 6C), or loss of the optic cup over time (Figure 6E) also reflect this component of vitreous traction. Although we could not document vitreopapillary traction on OCT, one eye with unilateral worsening optic disc edema (Figure 6A) had strong vitreomacular traction with dense premacular hard exudate, so we cannot exclude contribution of occult vitreous traction at disc. The dramatic recovery of elevation of ONH and retina after vitreoretinal surgery also supports our premise (Figure 7).

We observed that all of these optic disc changes had occurred after laser photocoagulation treatment. Laser photocoagulation might affect contraction of fibrovascular membrane or vitreous contracture with increasing vitreopapillary traction. Previous papers pointed out this possibility in FEVR10, and this is recognized in other disease such as diabetic retinopathy; however, it is difficult to differentiate any contribution of laser treatment to these changes from simply the disease affecting the vitreoretinal interface.

Recognizing the role of anteroposterior vitreous traction across the retina and optic nerve in the pathogenesis of FEVR in young children

Based on the OCT evidence, we believe that anteroposterior traction by the vitreous should be considered as one of the main pathophysiologic factors in FEVR in young children in addition to tangential and circumferential traction in the region of the peripheral fibrovascular tissue (Figure 8). At the beginning, the fibrovascular membrane develops at the border with peripheral avascular retina. As the fibrovascular membrane contracts, a peripheral retinal fold and retinal detachment begins to develop and progresses posteriorly (Centripetal progression). Meanwhile, antero-posterior ONH elevation and dragging and retinal elevation develops and progresses peripherally beyond the posterior pole (Centrifugal progression). Finally, when centripetally-progressing retinal fold bridges with centrifugally-progressing retinal elevation, radial retinal fold develops. Our hypothesis that vitreous has an important role in progression of FEVR in young children, can help to explain why FEVR progresses into the advanced stage despite sufficient peripheral laser treatment in some cases, as the purpose of laser photocoagulation is mainly focused on regressing active peripheral fibrovascular membranes.

Figure 8. Conceptual diagram of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) pathogenesis.

Left, In addition to retinal dragging due to the contraction of a peripheral fibrovascular membrane (red arrows), vitreous traction (blue arrows) is also an important factor in pathogenesis of FEVR in young children. The direction and the size of arrows represent those of tractional force. Right, from upper to lower: At the beginning, the fibrovascular membrane develops at the peripheral avascular retina. As the fibrovascular membrane contracts, a peripheral retinal fold with retinal detachment begins to develop and progresses posteriorly (centripetal progression). Meanwhile, through vitreous traction, optic nerve head elevation and dragging and retinal elevation develops and progresses peripherally beyond posterior pole (Centrifugal progression). Finally, when a centripetally progressing retinal fold bridges with a centrifugally progressing retinal elevation, the radial retinal fold develops.

While OCT imaging is of great use in comprehending these components of tractional elevation to the optic nerve and macula in preoperative planning, it is also useful during surgery to evaluate tractional effect on these stuctures and to monitor the response during and after vitreous and membrane removal. For FEVR surgical cases in young children, it is important to recognize that vitreous traction may be sufficient to elevate the surface of the ONH and retina, but unlike in older children and adults, this elevation will not usually be accompanied by a partial PVD. Thus while partial PVD is often watched for as an indicator of vitreoretinal traction in older children and adults, at this young age the vitreous remains attached and one should instead look for the signs of deformation of the underlying structures. Additional studies are underway to evaluate and optimize OCT visualization of these structures during vitreoretinal surgery.

This study has several limitations. First, because of retrospective design, there was no standardized follow-up time for examinations. Second, due to the limited number of patients and irregular intervals for follow up in our study, we did not perform significance testing, but only descriptive analysis of the OCT findings. Third, the image quality for some patients was suboptimal due to media opacities or the challenges of optimizing imaging early in our use of HHOCT. Acquiring high quality HHOCT images in infants and young children can be challenging for many reasons. Fourth, the image graders were not blinded to the OCT findings, which might have caused biased results. Finally, because of the very young ages of the FEVR patients in our study, there was limited data regarding visual function; thus we could not correlate OCT findings with functional outcome such as visual acuity or visual field. In young FEVR patients, in whom standard visual functional testing cannot be readily performed, visual evoked potential may be more informative because OCT informs us that the optic nerve may be affected even in the early stages of visible ONH dragging.

In summary, we report that HHOCT of the ONH and retina can provide valuable complementary information regarding vitreous status and enhance our understanding on the pathogenesis of FEVR in very young children. This information has not been sufficiently reflected by the conventional staging systems for FEVR, which for very young children, have been based on funduscopic and fluorescein angiographic findings. We believe that it is worthwhile to recognize and record the presence or absence of OCT-VPD in FEVR stages 2–4 in young children. We suggest that an annotation of D+ for OCT-VPD present and D− for absent would be of use when recording stage 2–4 FEVR. This would reflect the status of vitreous traction and its effects on the optic nerve and could be useful for relating this traction to future visual outcomes including the visual field. We point out the importance of recognizing the potential impact of vitreous traction on the ONH, as well as the peripheral retinal status in FEVR. This information could be valuable in preoperative assessment and in clinical monitoring, especially after laser treatment in young children.

Summary Statement.

In addition to retinal traction by peripheral fibrovascular membrane, strong anteroposterior traction by contraction of strongly adherent vitreous is a contributing factor during the progression of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy in infants.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Grant from Research Year of Inje University in 2015; The Hartwell Foundation; The Andrew Family Charitable Foundation; Grant Number R01 EY025009, R01 EY023039 from National Institute of Health (NIH); Grant Number P30 EY001583 from the National Eye Institute (NEI); Grant Number 1UL1RR024128-01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of Inje University, NIH, NEI, or NCRR. The sponsors or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Toth recieves royalties through her university from Alcon and had prior research support from Bioptigen and Genentech. She also has unlicensed patents pending in OCT imaging and analysis. No other authors have financial disclosures. No authors have a proprietary interest in the current study.

References

- 1.Criswick VG, Schepens CL. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969;68:578–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(69)91237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyakubo H, Hashimoto K, Miyakubo S. Retinal vascular pattern in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1524–30. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pendergast SD, Trese MT. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Results of surgical management. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1015–23. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranchod TM, Ho LY, Drenser KA, et al. Clinical presentation of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2070–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kashani AH, Learned D, Nudleman E, et al. High prevalence of peripheral retinal vascular abnormalities in family members of patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boonstra FN, van Nouhuys CE, Schuil J, et al. Clinical and molecular evaluation of probands and family members with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4379–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan M, Yang Y, Yan H, et al. Increased posterior retinal vessels in mild asymptomatic familial exudative vitreoretinopathy eyes. Retina. 2015;36:1209–15. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan M, Yang Y, Yu S, et al. Posterior pole retinal abnormalities in mild asymptomatic FEVR. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;56:458–63. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi MM, Ciaccia S, Trese MT, Capone A. Posterior hyaloid contracture in pediatric vitreoretinopathies. Retina. 2006;26:S38–41. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000244287.63757.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yonekawa Y, Thomas BJ, Drenser KA, et al. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy: spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the vitreoretinal interface, retina, and choroid. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2270–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katagiri S, Yokoi T, Nishina S, Azuma N. Structure and morphology of radial retinal folds with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:666–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimouchi A, Takahashi A, Nagaoka T, et al. Vitreomacular interface in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Int Ophthalmol. 2013;33:711–5. doi: 10.1007/s10792-012-9707-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel CK, Chen SD, Farmery AD. Optical coherence tomography under general anesthesia in a child with nystagmus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:1127–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allingham MJ, Cabrera MT, O’Connell RV, et al. Racial variation in optic nerve head parameters quantified in healthy newborns by handheld spectral domain optical coherence tomography. J AAPOS. 2013;17:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabrera MT, O’Connell RV, Toth CA, et al. Macular findings in healthy full-term Hispanic newborns observed by hand-held spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2013;44:448–54. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20130801-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maldonado RS, Izatt JA, Sarin N, et al. Optimizing hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging for neonates, infants, and children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2678–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viehland C, Keller B, Carrasco-Zevallos OM, et al. Enhanced volumetric visualization for real time 4D intraoperative ophthalmic swept-source OCT. Biomed Opt Express. 2016;7:1815–29. doi: 10.1364/BOE.7.001815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day S, Maldonado RS, Toth CA. Preretinal and intraretinal exudates in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Retina. 2011;31:190–1. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182019c04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benson WE. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1995;93:473–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shukla D, Singh J, Sudheer G, et al. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR). Clinical profile and management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003;51:323–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gow J, Oliver GL. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. An expanded view. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;86:150–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1971.01000010152007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:991–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reese AB, Stepanik J. Cicatricial stage of retrolental fibroplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1954;38:308–16. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(54)90846-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulenburg WE, Prendiville A, Ohri R. Natural history of retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:837–43. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.11.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronan SM, Tran-Viet KN, Burner EL, et al. Mutational hot spot potential of a novel base pair mutation of the CSPG2 gene in a family with Wagner syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1511–9. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nouhyuys CEv. Signs, complications, and platelet aggregation in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:34–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76893-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim M, Kim TW, Weinreb RN, Lee EJ. Differentiation of parapaillary atrophy using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1790–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canny CL, Oliver GL. Fluorescein angiographic findings in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94:1114–20. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1976.03910040034006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sebak J, Nguyen N. Vitreous embryology and vitreo-retinal developmental disorders. In: Hartnett ME, editor. Pediatric retina. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda T, Fujikado T, Tsujikawa, et al. Vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous or tractional retinal detachment with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1081–5. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothman AL, Folgar FA, Tong AY, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography characterization of pediatric epiretinal membranes. Retina. 2014;34:1323–34. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamane T, Yokoi T, Nakayama Y, et al. Surgical outcomes of progressive tractional retinal detachment associated with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:1049–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilmour DF. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and related retinopathies. Eye. 2015;29:1–14. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sebag J. Age-related changes in human vitreous structure. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1987;225:89–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02160337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]