Structured Abstract

Purpose

To examine the features of the Tapetal-Like Reflex (TLR) in female carriers of RPGR-associated retinopathy by means of adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT).

Methods

Nine molecularly-confirmed RPGR carriers and three healthy controls underwent ocular examination and the following retinal imaging modalities: color photography, near-infrared reflectance, fundus autofluorescence, SDOCT and AOSLO. After identifying TLR areas across all imaging modalities, normalized local contrast of outer retinal bands on SDOCT was calculated and AOSLO-acquired photoreceptor mosaic analysis was performed.

Results

Seven carriers had TLR areas, which co-localized with increased rod photoreceptor reflectivity on confocal AOSLO and reduced cone photoreceptor densities. Parafoveal TLR areas also exhibited reduced local contrast (i.e. increased reflectivity) of the outer retinal bands on SDOCT (Inner Segment Ellipsoid Zone and Outer Segment Interdigitation Zone). Healthy controls did not show TLR.

Conclusions

The cellular resolution provided by AOSLO affords the characterization of the photoreceptor mosaic in RPGR carriers with a tapetal-like reflex. Features revealed include reduced cone densities, increased cone inner segment diameters and increased rod outer segment reflectivity.

Keywords: Adaptive optics, carriers, heterozygotes, imaging, retinitis pigmentosa, tapetal-like reflex

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa is a clinically heterogeneous group of progressive disorders characterized by night-blindness and constriction of peripheral visual field in the early stages, leading to subsequent central visual loss, and is associated with over 100 different genes.1–6 X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP) is often of earlier onset and more rapidly progressive than other forms, and accounts for between 10–20% of all cases, with 70–80% of these due to sequence variants in the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) gene.1, 7–9 There are multiple RPGR isoforms arising from alternative splicing or post-translational modification,10 which are variably expressed in different tissues (lung, kidney, retina, brain, testis); suggesting tissue-specific splicing with tissue-specific functions.11 The two major isoforms are the constitutive RPGR exon 1–19 and RPGR ORF15, with the latter representing the most highly expressed in photoreceptors.12 Previous reports suggest disease-causing variants are found in exons present in isoform RPGR ORF15, with only one in exons 15–19, supporting the importance of RPGR ORF15 in photoreceptors.13–15 While RPGR protein function is not completely characterized, it is believed to play a role in ciliary transport, with malfunction leading to early onset of visual symptoms usually in the first or second decade of life and progressing rapidly, with severe visual impairment by the fourth decade.1, 3, 12, 16

Obligate XLRP carriers may either be asymptomatic or mildly affected, but are rarely as severely affected as males.1, 17–22 Observed deficits include visual field constriction,23 and loss of rod and cone responses on psychophysical testing,17, 18 and electroretinography.17, 19, 22 The most common observation in obligate XLRP carriers is a radial pattern of hyper-reflectivity, frequently called a tapetal-like reflex (TLR). Unlike a “true” tapetal reflex seen in the eyes of certain vertebrates,24 which is a contiguous reflecting surface, the hyper-reflectivity in XLRP carriers manifests as patchy radial streaks of golden appearing retina.

A small number of studies have explored the appearance of the TLR and its cellular origin ex vivo and even fewer in vivo. Cideciyan and Jacobson measured the size of hyper-reflective particles by digitally magnifying film-based color fundus photos, and deemed the hyper-reflective particles to be consistent with the size of cone inner segments.25 A few years later, Berendschot et al. provided evidence that it was rather rod and cone photoreceptor outer segments that contribute to the TLR appearance in three XLRP carriers.26 More recently, Park et al. investigated XLRP carriers with a TLR (n=5) using an adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscope (AOSLO) but without being able to resolve rods.27

In this study, we have undertaken deep phenotyping of molecularly-confirmed carriers of RPGR-associated RP. Color fundus photography, near infrared (NIR) reflectance, fundus autofluorescence (FAF), spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT) and confocal/non-confocal AOSLO were used to explore the spatial correlation and composition of the fundus TLR. Here we show that the TLR manifests as (a) increased reflectivity (or in other words, diminished local contrast) in the appearance of outer retinal bands in SDOCT scans, and (b) bright reflecting rod photoreceptor outer segments, reduced cone densities and enlarged cone inner segment diameters in AOSLO images of the photoreceptor mosaic.

Methods

Subjects

Nine molecularly-confirmed RPGR carriers (28–62 years of age) and three non-carrier females (24–29 years of age) were enrolled. All carriers studied were from unrelated families. Seven consisted of the mothers of affected males, one was the sister of an affected male (MM_0010) and one was the maternal aunt of an affected male (MM_0039). The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Moorfields Eye Hospital ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after explanation of the nature and potential consequences of the study prior to enrolment.

Pupils were dilated using one drop each of phenylephrine (2.5%) and tropicamide (1%) before retinal imaging. Axial length was measured using a Zeiss IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany), to correct the lateral scale of OCT and AOSLO images.

Retinal Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography, Color Reflectance, Near-Infrared Reflectance, and Fundus Autofluorescence

All participants underwent SDOCT using an Envisu system (Bioptigen, Morrisville, NC, USA). Horizontal and vertical (where possible) rectangular (7×1 mm) volume scans (750 A-scans/B-scan, 10 B-scans/volume, each derived from an average of 15 frames) were acquired while asked to fixate on the center of a cross. The foveal center was estimated as the location where inner retinal thickness was minimal. At least 20 frames belonging to the foveal center were subsequently registered (to correct for eye motion) and averaged (to improve signal to noise ratio) using the ImageJ28 plugin StackReg.29

Pixel intensities in the linear display (converted from the original logarithmic scale) were first measured for the outer retinal bands corresponding to the inner segment ellipsoid zone (EZ), outer segment interdigitation zone (IZ), and retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch’s membrane (RPE/BrM). A five-pixel-wide longitudinal reflectivity profile (LRP) was obtained (averaging the values across five consecutive lateral positions) at the foveal center (0 mm), and at 1 mm and 2 mm temporally/nasally/superiorly and inferiorly to the foveal center.30 These locations were chosen to represent regions (in carriers) with a TLR (2 mm) and without a TLR (0 mm) and the respective transition zones (1 mm), as shown in Figure 1 with the aid of red concentric rings. Normalized local contrast was then calculated using a previously defined formula.31 Comparison of these contrast values per eccentricity and retinal layer was performed by means of box plots (depicting the interquartile range (IQR), median and whiskers extending out to 1.5 × IQR). Statistical analyses were conducted using Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

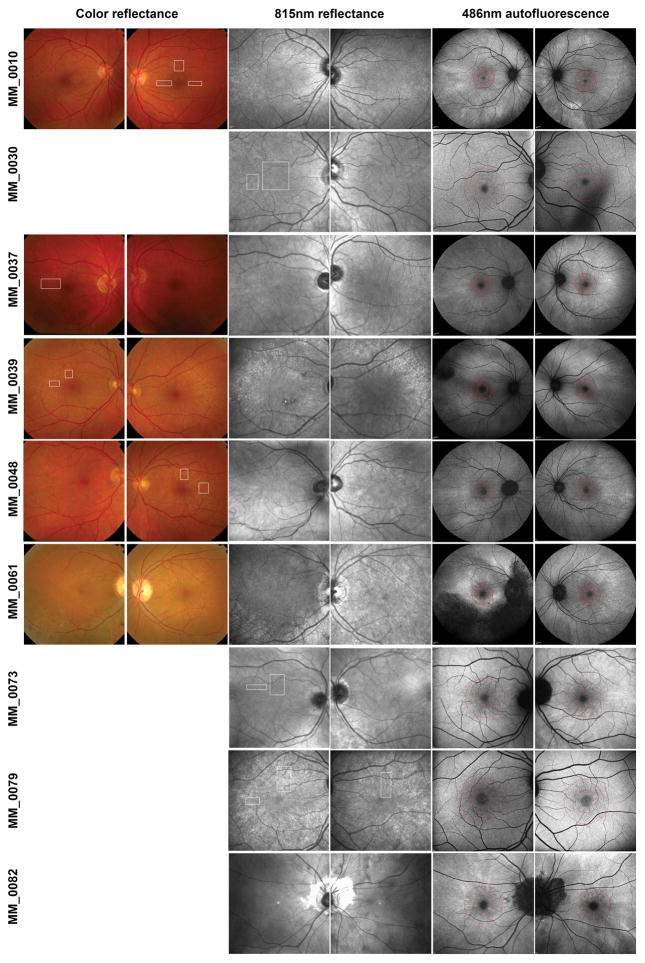

Figure 1. Multimodal imaging in carriers of RPGR-associated RP.

Color fundus photos (where available), near infrared (NIR) reflectance and fundus autofluorescence (FAF) of all our RPGR-associated RP carriers. White rectangles indicate areas that were imaged with AOSLO on a cellular scale. The photoreceptor mosaic could not be resolved for MM_0061 and MM_0082. Concentric rings on FAF are centered on the fovea and correspond to 1 mm (inner) and 2 mm (outer) away from it to aid comparison across modalities (including OCT analysis).

Subjects also underwent fundus color photography (macula centered, 50° field of view) using a mydriatic retinal camera (Topcon Ltd, Newbury, UK) and NIR (815 nm) reflectance fundus imaging (30° field of view) followed by blue (486 nm) FAF imaging (55° or 30° field of view) using the Heidelberg Spectralis (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Each FAF image was created from a registered average of at least 12 raw frames by means of the automatic real time feature.

Photoreceptor Mosaic Imaging

At least one eye from each subject was imaged using a custom-built AOSLO that captured confocal images (focused on the outer segments of the photoreceptor layer) as previously described32. Briefly, the imaging light source was a 790nm super luminescent diode (SLD) (Superlum, Carrigtwohill, County Cork, Ireland), while wavefront sensing was performed using an 850nm SLD (also from Superlum). Monochromatic wavefront aberrations were corrected using a 97-actuator deformable mirror (ALPAO, Biviers, France) with a 14 mm clear aperture. Image sequences consisting of 150 frames were recorded at different locations across the central fovea and parafovea using a fixation target. The raw frames from these sequences were first desinusoided and then registered33 before being manually tiled into a single montage (Adobe Photoshop CS6; Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Simultaneous confocal and non-confocal split detection AOSLO images34 were obtained in absolute spatial and temporal registration during the follow-up of one carrier (MM_0048).

TLR areas were identified in macroscopic modalities and guided the (microscopic) photoreceptor mosaic AOSLO imaging session to obtain TLR locations (white rectangles, Figure 1) for further cellular analysis. Two paired regions, one within a TLR area and another outside a TLR but adjacent to one (≤50μm), were selected from 7 RPGR carriers post-acquisition. Matched eccentricities were used for analysis in the 3 non-carrier controls. All cone photoreceptors in the cropped regions (100×100μm) were manually identified – their number was divided by that area to derive an estimate of the cone density for each image.

Serial photoreceptor mosaic images were obtained in a subset of carriers (MM_0037, MM_0039 and MM_0048) to longitudinally assess the TLR appearance on a cellular scale. Finally, with the aid of the non-confocal split detection AOSLO modality, cone (both outer and inner segments) and rod (outer segments) photoreceptors were identified in a TLR area (MM_0048) and their reflectivity values were measured. Pixel intensities from the center of all identified photoreceptors were plotted for direct comparison between cones and rods and between a carrier and an unaffected individual. If rod outer segments did not waveguide light back to the detector and thereby appeared dark in confocal AOSLO, they were not included in the reflectivity analysis as their exact location and number could not be identified from the non-confocal image (due to their much smaller diameter), in direct contrast to cone photoreceptors. This also precluded any rod counting analysis.

Results

Carrier demographics, best-corrected visual acuity and genotypes are summarized in Table 1. Ophthalmic appearances are shown in Figure 1. Carriers MM_0061 and MM_0082 were excluded from analysis due to poor scans/image quality and the inability to resolve photoreceptor mosaics in sufficient quality.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and genetic results of RPGR-associated RP carriers (n=9).

| Carrier ID | Age | BCVA (OD,OS) | MEH Pedigree | Exon | Mutation | Protein Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM_0010 | 28 | 6/5,6/5 | 13724 | Exon 8/Intron 8 | c.836_934+1276del | Splicing |

| MM_0030 | 49 | 6/5,6/6 | 20372 | Exon 10 | c.1243_1244delAG | p.Arg415Glyfs*37 |

| MM_0037 | 43 | 6/48,6/6 | 66 | ORF15 | c.2624_2643del20 | p.Glu875Glyfs*197 |

| MM_0039 | 62 | 6/5,6/9 | 4549 | ORF15 | c.2650G>T | p.Glu884* |

| MM_0048 | 55 | 6/9,6/9 | 180 | ORF15 | c.2045_2046dupGT | p.Arg683Valfs*15 |

| MM_0061 | 62 | 6/12,6/9 | 18426 | ORF15 | c.2236_2237delGA | p.Glu746Argfs*23 |

| MM_0073 | 34 | 6/6,6/6 | 20844 | ORF15 | c.2405_2406delAG | p.Glu802Glyfs*32 |

| MM_0079 | 52 | 6/5,6/6 | 3878 | ORF15 | c.2907_2910delAGGA | p.Gly970Lysfs*118 |

| MM_0082 | 47 | 6/6,6/5 | 5201 | ORF15 | c.2238delA | p.Glu747Argfs*68 |

Reference sequence NM_001034853.1; Abbreviations: BCVA, Best-corrected Visual Acuity; MEH, Moorfields Eye Hospital; ORF, Open Reading Frame

Color Fundus, NIR Reflectance and FAF retinal imaging

Apart from color fundus images that were obtained in five out of nine carriers, all other modalities were obtained in all RPGR carriers (Figure 1). In all carriers, a TLR was observed in color fundus (where available) and NIR reflectance, albeit to a varying intensity and extent, both between eyes of the same carrier and across carriers (intra-familial variability and ocular asymmetry). FAF imaging in our carrier cohort revealed radial patterns of increased autofluorescence signal in all images. These patterns did not always co-localize with the TLR areas observed in other modalities, but direct comparison could not be performed universally due to the different fields of view across modalities. None of the non-carrier controls showed a TLR in any modality. MM_0061 was severely affected, presenting with asymmetrical peripheral pigmentary changes, RPE atrophy and vascular attenuation.

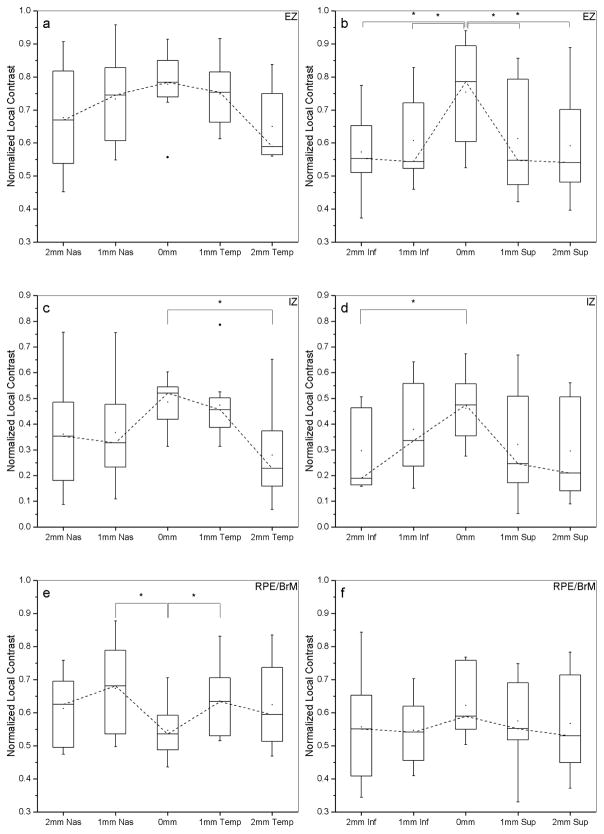

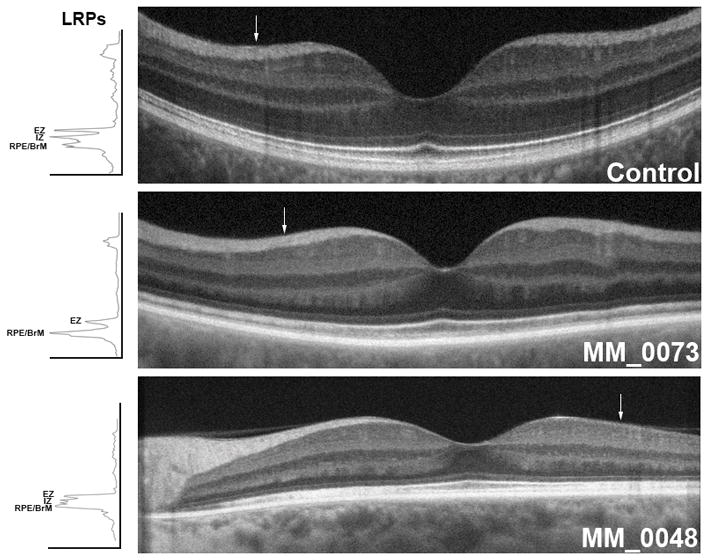

Outer Retinal Hyper-Reflective Bands on SDOCT

Fundus TLR was associated with changes in appearance of the outer retinal layers (EZ and IZ) on SDOCT (Figure 2). This is quantitatively analyzed and presented in Figure 3, which shows the contrast reduction in those layers while traversing from central (0 mm) non-TLR areas towards more peripheral (2 mm) TLR areas, in all 4 directions (superior, inferior, temporal, nasal). Asterisks denote statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level (paired t-test). There was a significant reduction in the EZ local contrast between 0 mm (0.75±0.1) and 2 mm (0.57±0.1) inferiorly (t(7)=4.25, p=0.0037) and between 0 mm and 2 mm superiorly (0.59±0.1) (t(7)=3.08, p=0.017). Similar significant contrast reductions were noted in the IZ layer between 0 mm (0.48±0.09) and 2 mm (0.27±0.1) temporally (t(7)=2.75, p=0.028) and between 0 mm (0.46±0.1) and 2 mm (0.31±0.1) inferiorly (t(5)=4.24, p=0.008).

Figure 2. Outer retinal SDOCT local contrast measured in carriers with a TLR.

Transfoveal SDOCT scans from a non-carrier female control and two carriers with representative outer retinal layers exhibiting a TLR. White arrow on each image corresponds to the location of the 5 pixel wide longitudinal reflectivity profile (LRP) shown to the left of the scans. Every arrow is 2 mm away from the foveal center. MM_0073’s LRP revealed 2 instead of 3 (as in the Control scan, above) hyper-reflective peaks. MM_0048’s LRP revealed all 3 outer retina layers but with diminished local contrast compared to the Control. EZ, Ellipsoid Zone; IZ, Interdigitation Zone; RPE/BrM, Retinal Pigment Epithelium/Bruch’s Membrane.

Figure 3. Comparison of normalized local contrast across eccentricities for carriers exhibiting a TLR.

Left column (panels a,c,e) plots are for horizontal and right column (panels b,d,f) are for vertical transfoveal SDOCT line scans of carriers exhibiting a TLR with available SDOCT scans. Box plots depict the interquartile range (IQR), median and whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR. Dashed lines join the median values. Filled squares indicate mean values and filled circles indicate outliers. Outer retina layers are designated as Ellipsoid Zone (EZ), Interdigitation Zone (IZ) and Retinal Pigment Epithelium/Bruch’s Membrane (RPE/BrM), top to bottom rows. Normalized local contrast values at the foveal center (0 mm) were compared with those parafoveally at 1 mm and at 2 mm. Statistically significant differences are denoted with asterisks (paired t-tests at the 0.05 level).

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of the Photoreceptor Mosaic

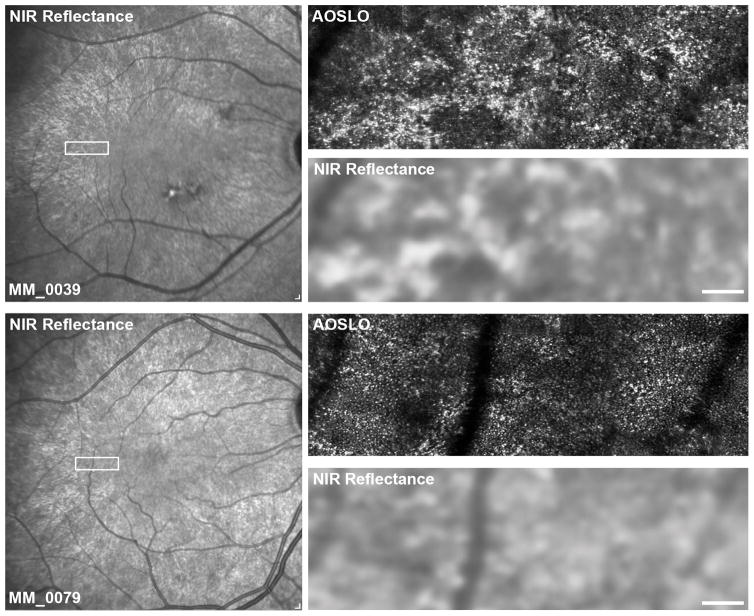

The photoreceptor mosaic could be resolved in the confocal AOSLO images from 7 out of 9 carriers at the regions of interest (8 eyes in total). The fundus TLR observed on color fundus and NIR reflectance images co-localized with areas of highly reflective rod photoreceptors in these 7 carriers. Although, the locations imaged by means of AOSLO (white rectangles, Figure 1) were chosen so as to represent TLR areas appearing in the macroscopic modalities, this could not be achieved in all cases (MM_0030 and MM_0073). Lack of color fundus images in these two carriers, also hindered the confirmation of a TLR pattern macroscopically.

Cone photoreceptor density in the 14 regions of interest (2 each from 7 carriers) in TLR regions were on average 29.4% (range 12.9 – 47.8%) reduced compared to the immediately adjacent, non-TLR regions of interest (Figure 5). In contrast, 6 adjacent regions from the non-carrier controls (2 each from 3 controls) had an average difference of 1.7% (range 0.6 – 4.0%).

Figure 5. TLR areas are associated with localized cone loss, compared to non-TLR areas in carriers of RPGR-associated RP.

Shown is a region of temporal retina from a healthy control (MM_0136), and two RPGR-associated RP carriers with a highlighted region of interest (ROI) (square, top row) in the nasal and temporal retina, respectively (MM_0010 and MM_0048) containing both TLR and non-TLR regions. These ROIs in the top row NIR reflectance images correspond to the location of the confocal AOSLO images below. The squares correspond to either regions of photoreceptor mosaic outside the TLR regions or to photoreceptor regions within the TLR. Scale bar is 100 μm. Adjacent regions in the non-carrier female show virtually no difference in cone densities. Conversely, in RPGR-associated RP carriers the TLR regions are associated with decreased cone densities and increased rod outer segment brightness.

Reflectivity analysis of a TLR area in one of the carriers (MM_0048) approximately 2.2° away from the fovea revealed that 96% (24 out of 25) of cone photoreceptor outer segments had a dim appearance of an average (±Standard Deviation, SD) intensity value of 103 (±48), whereas rod photoreceptor outer segments were on average (±SD) brighter (148±80) with 39% of them (26 out of 66) having intensities of at least 200 (Supplement Figure 1). Reflectivity values of cones (n=83) and rods (n=85) from an unaffected individual (MM_0136) were substantially lower (59±20 and 21±10, respectively). Carriers’ cone photoreceptors have evidently enlarged inner segment diameters qualitatively illustrated in the non-confocal image compared to the non-carrier control.

Longitudinal Observation of TLR in the Photoreceptor Mosaic

Representative TLR appearances of the photoreceptor mosaic for the three carriers that were imaged 19 weeks apart (MM_0037 and MM_0039) and 42 weeks apart (MM_0048) are presented in Supplement Figure 2. The increased reflectivity of these TLR areas co-localized across time with no apparent brightness changes (qualitatively assessed).

Discussion

FAF appearances in the majority of our carrier cohort showcased the radial patterns of increased AF in the rod-rich ring-shaped area around the fovea at the eccentricity of the optic disc, corroborating previous reports35, 36. In some of our carriers images are limited to a 30° field of view precluding confirmation of these patterns. Future relevant studies should aim for wider field of view (55°) FAF imaging.

OCT reflectivity analysis revealed reduced normalized contrast across outer retinal layers in TLR areas compared to non-TLR areas indicating higher reflectivity originating from the EZ and IZ photoreceptor interfaces. Due to the low transverse resolution of SDOCT it is not possible to distinguish the relative contribution of cones and rods populating these layers, hence AOSLO imaging was the next step to achieve this goal.

Our study is the first to characterize the photoreceptor mosaic of TLR areas in RPGR carriers in vivo. Namely, the carriers’ photoreceptor mosaic features are shown to comprise of reduced cone densities within TLR areas compared to non-TLR areas, increased cone inner segment diameters compared to controls and increased rod outer segment reflectivity compared to cone outer segments. Previous studies reported that the TLR likely originates from cone photoreceptors25, 27; in our cohort this was not the case, with only a very small percentage of cones appearing highly reflective (in direct contrast to rods). Overall, it appears that both rod and cone photoreceptors contribute towards the TLR, i.e. are on average brighter than their non-carrier counterparts. Berendschot et al. were the first to report that the TLR originates at the outer segment of the photoreceptors;26 herewith our study provides evidence that more specifically it is almost exclusively rod photoreceptor outer segments which give the TLR appearance macroscopically (Figures 4, 5). This conclusion is drawn from the evidence high-resolution imaging offers: configuration of small circular structures, around larger cone-sized areas of reduced reflectivity (Supplement Figure 1). By definition, light from the RPE and inner segments is rejected by confocal AOSLO, hence the rod outer segments alone are contributing to this increased reflectivity.

Figure 4. TLR appearance in carriers of RPGR-associated RP – co-localization of NIR reflectance and confocal AOSLO modalities.

Shown are confocal AOSLO and matching NIR reflectance images from two carriers (MM_0039 and MM_0079). The rectangles on the NIR reflectance images indicate the areas enlarged on the right. The TLR patterns seen in NIR reflectance are clearly visible in the cellular arrangement, with rods of increased brightness, in contrast to cones. Scale bars are 100 μm.

Whether the TLR appearance is the result of disruption of cones, rods, or both with/without other factors cannot be answered from this study. Functional testing in XLRP carriers has revealed that both cones and rods are equivalently affected37, 38 however due to the variability both between and within carriers (inter-ocular), definitive conclusions cannot be drawn for all carriers.

Identifying the objects (here, rod outer segments) that appear brighter than their surroundings to give rise to the TLR appearance macroscopically does not necessarily answer a more complicated question of what is the cause of such appearance. Although our study was not designed to objectively establish the latter, we can suggest potential mechanisms of the origin of the TLR. The media surrounding rods (either the cones or the organization of the RPE apical extensions, or both) may be disrupted in the form of an altered refractive index and this may in turn cause the TLR appearance partly because the rod signal is believed to depend on the refractive index difference between the interface of the rods and their surroundings. So, if the pair of adjacent media refractive indices closer match one another (rather than differ) less light is waveguided and thus reflected (TLR).

Since the RPGR gene product has been shown to be ubiquitously expressed in tissue-specific splice forms,10, 12, 39 at least two different hypotheses could hold true for the TLR mechanism. The first is that aberrant RPGR in the RPE alters the interaction between the apical appendages of the RPE cells and the rod outer segment tips, thus changing the refractive index and altering the observed signal. Second, RPGR expressed in the rod photoreceptors alters their shape and composition (due to trafficking defects) and thus changes their interaction with the RPE and the optical signal they generate, as has been suggested in Oguchi disease.40 However, multiple studies have sought to identify RPGR expression patterns; the ORF15 containing isoform is only found in photoreceptors.10, 39 This suggests that RPGR expressed in RPE is likely a different isoform than that expressed in photoreceptors and is potentially unaffected by the ORF15 sequence variants in the majority of our carriers’ cohort. Further work from Beltran et al. suggested both cone and rod opsin mislocalization (in the same retinal patches) to the inner segments and outer nuclear layer in two canine models of RPGR-associated disease.41 If such structural changes exist and to what extent affect the appearance of the photoreceptor mosaic in RPGR carriers remains to be elucidated.

Our results corroborate ex vivo retinal histopathology studies in RPGR carriers (humans and animal models) showing reduction in photoreceptor numbers41–43. Additionally, loss of the outer segment, non-uniform cone spacing, and both shorter and broader cone inner segments (similar rod changes, but to a lesser extent) have been documented throughout the retina, including the perifoveal region. In order to assess outer segment length in vivo, AO-OCT would prove a complimentary imaging modality with better axial and lateral resolution compared to SDOCT towards a more complete and precise characterization of outer retinal structure in RPGR carriers.

The increased reflectivity of the rod outer segments in confocal AOSLO images was broadly consistent across all 7 carriers. An area that should be further explored in the future is microperimetry in TLR areas.20, 44 Previous studies suggest that there was a reduction in photopic and scotopic performance in TLR areas; however stimuli positioning may have not been accurate enough to exclusively target small streaks of such golden strands. New, adaptive optics and high-fidelity eye-tracking schemes allow stimulus presentation with cellular precision45 and have been demonstrated in other retinal conditions.46 Application of these techniques in RPGR carriers expressing patterns of fundus TLR would be informative.

Our study has some limitations. First, we did not obtain color retinal photographs from 4 carriers in order to assess the full macroscopic TLR appearance across our cohort. Second, we did not control for the adaptation state (photopic versus scotopic vision) prior to each imaging modality47 to compensate for potential fluctuations of the TLR appearance with varying retinal exposure to light. Nevertheless, we have (qualitatively) shown that three of our carriers showed no fluctuations in TLR intensities across visits. Third, our sample size was relatively limited (n=7), albeit - to the best of our knowledge - it is the only study with in vivo cellular imaging down to rod resolution. Lastly, the lack of non-confocal split detection AOSLO imaging for all but one of the carriers precluded the expansion of our photoreceptor reflectivity analysis due to the challenges in reliably discriminating between cone and rod photoreceptors, as well as distinguishing neighboring bright rods as individual photoreceptors rather than potentially confusing them for cones, using the confocal modality alone.

Cideciyan and Jacobson drew attention to the increased reflectivity in color fundus reflectance images taken in XLRP carriers, and this finding has been supported by other imaging studies.25 Structural and functional cellular mosaicism due to random X-chromosome inactivation has also been reported in other X-linked conditions such as cone dystrophy, blue cone monochromatism, X-linked retinoschisis and choroideremia.48–52 We extend these aforementioned observations in a cohort of molecularly-confirmed carriers of XLRP harboring disease-causing sequence variants in RPGR and provide evidence that cone density is reduced in TLR areas compared to adjacent non-TLR ones and that increased rod outer segment reflectivity accounts for the observed TLR in these same areas. It remains to be determined whether baseline photoreceptor TLR and associated cellular changes observed on AOSLO are prognostic indicators of the magnitude and/or rate of progression a carrier may experience over time.

Supplementary Material

Confocal and non-confocal split-detection AOSLO images depicting cone and rod outer segments and cone inner segments, respectively from an unaffected individual (left, MM_0136) and a carrier (right, MM_0048). Cones were confirmed as such with the aid of the non-confocal image and are marked with turquoise dots. Rod photoreceptors occupying the space between cones are marked with yellow dots. The pixel intensity for all marked photoreceptors was measured on the confocal image using ImageJ and their normalized histogram is plotted below. Approximate location is 2° away from the fovea for both subjects, with all images being 55μm across.

Carriers MM_0037 (top row) and MM_0039 (middle row) imaged 19 weeks apart and MM_0048 (bottom row) imaged 42 weeks apart using confocal AOSLO showing cone and rod outer segments. Scale bars are 100μm.

Summary Statement.

Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy affords the characterization of the photoreceptor mosaic in RPGR carriers with a tapetal-like reflex. Features revealed include reduced cone densities, increased cone inner segment diameters and increased rod outer segment reflectivity.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, National Eye Institute (NEI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers R01EY017607, R01EY025231, P30EY001931, T32GM080202, T32EY014537 and U01EY025477, Fight For Sight (UK), Moorfields Eye Hospital Special Trustees [R140032A], Moorfields Eye Charity [MEC1512B], the Foundation Fighting Blindness (USA), Retinitis Pigmentosa Fighting Blindness, Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB), and The Wellcome Trust [099173/Z/12/Z]. Michel Michaelides is supported by an FFB Career Development Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NIHR.

The authors acknowledge the help of Dr. Jessica Gardner with parts of this work and are grateful to all participants.

Footnotes

Setting: Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, Department of Genetics, London, UK.

Authors have no financial/conflicting interests to disclose pertaining to this work.

The study was presented in part at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) conference 2014 (Orlando, FL) and at the OSA Fall Vision Meeting 2016 (Rochester, NY).

References

- 1.Bird AC. X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59(4):177–199. doi: 10.1136/bjo.59.4.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Churchill JD, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, et al. Mutations in the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa genes RPGR and RP2 found in 8.5% of families with a provisional diagnosis of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(2):1411–1416. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daiger SP, Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ. Genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Genet. 2013;84(2):132–141. doi: 10.1111/cge.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebenezer ND, Michaelides M, Jenkins SA, et al. Identification of novel RPGR ORF15 mutations in X-linked progressive cone-rod dystrophy (XLCORD) families. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(6):1891–1898. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishman G, Farber M, Derlacki D. X-linked retinitis pigmentosa profile of clinical findings. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(3):369–375. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130395029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. The Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1795– 1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger W, Kloeckener-Gruissem B, Neidhardt J. The molecular basis of human retinal and vitreoretinal diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(5):335– 375. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shu X, Black GC, Rice JM, et al. RPGR mutation analysis and disease: an update. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(4):322–328. doi: 10.1002/humu.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tee JJL, Smith AJ, Hardcastle AJ, Michaelides M. RPGR-associated retinopathy: clinical features, molecular genetics, animal models and therapeutic options. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(8):1022–1027. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan D, Swain PK, Breuer D, et al. Biochemical characterization and subcellular localization of the mouse retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (mRpgr) J Biol Chem. 1998;273(31):19656–19663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirschner R, Rosenberg T, Schultz-Heienbrok R, et al. RPGR transcription studies in mouse and human tissues reveal a retina-specific isoform that is disrupted in a patient with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(8):1571–1578. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.8.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He S, Parapuram SK, Hurd TW, et al. Retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) protein isoforms in mammalian retina: Insights into X-linked retinitis pigmentosa and associated ciliopathies. Vision Res. 2008;48(3):366– 376. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayyagari R, Demirci F, Liu J, et al. X-linked recessive atrophic macular degeneration from RPGR mutation. Genomics. 2002;80(2):166– 171. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vervoort R, Lennon A, Bird AC, et al. Mutational hot spot within a new RPGR exon in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 2000;25(4):462–466. doi: 10.1038/78182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vervoort R, Wright AF. Mutations of RPGR in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3) Hum Mutat. 2002;19(5):486–500. doi: 10.1002/humu.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright AF, Shu X. Focus on molecules: RPGR. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85(1):1– 2. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berson EL, Rosen JB, Simonoff EA. Electroretinographic testing as an aid in detection of carriers of X-chromosome-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87(4):460–468. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ernst W, Clover G, Faulkner DJ. X-linked retinitis pigmentosa: reduced rod flicker sensitivity in heterozygous females. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;20(6):812–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fishman G, Weinberg A, McMahon T. X-linked recessive retinitis pigmentosa: Clinical characteristics of carriers. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104(9):1329–1335. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210083030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genead MA, Fishman GA, Lindeman M, et al. Structural and functional characteristics in carriers of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa with a tapetal-like reflex. Retina. 2010;30(10):1726–1733. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181dde629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kousal B, Skalicka P, Valesova L, et al. Severe retinal degeneration in women with a c.2543del mutation in ORF15 of the RPGR gene. Mol Vision. 2014;20:1307–1317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vajaranant TS, Seiple W, Szlyk JP, Fishman GA. Detection using the multifocal electroretinogram of mosaic retinal dysfunction in carriers of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(3):560– 568. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grover S, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, Lindeman M. A longitudinal study of visual function in carriers of X-linked recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(2):386– 396. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicol J. Tapeta lucida of vertebrates. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1981. Vertebrate Photoreceptor Optics; pp. 401–431. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cideciyan AV, Jacobson SG. Image analysis of the tapetal-like reflex in carriers of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35(11):3812–3824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berendschot TT, DeLint PJ, van Norren D. Origin of tapetal-like reflexes in carriers of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(13):2716–2723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pyo Park S, Hwan Hong I, Tsang SH, Chang S. Cellular imaging demonstrates genetic mosaicism in heterozygous carriers of an X-linked ciliopathy gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013 Nov;21(11):1240–1248. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abramoff M, Magalhaes P, Ram S. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophot Int. 2004;11(7):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thevenaz P, Ruttimann UE, Unser M. A pyramid approach to subpixel registration based on intensity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 1998;7(1):27–41. doi: 10.1109/83.650848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y, Cideciyan AV, Papastergiou GI, et al. Relation of optical coherence tomography to microanatomy in normal and rd chickens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(12):2405–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanna H, Dubis AM, Ayub N, et al. Retinal imaging using commercial broadband optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(3):372–376. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.163501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubra A, Sulai Y. Reflective afocal broadband adaptive optics scanning ophthalmoscope. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2(6):1757–1768. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubra A, Harvey Z. Biomedical Image Registration. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2010. Registration of 2D images from fast scanning ophthalmic instruments; pp. 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scoles D, Sulai YN, Langlo CS, et al. In vivo imaging of human cone photoreceptor inner segments. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(7):4244–4251. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogino K, Oishi M, Oishi A, et al. Radial fundus autofluorescence in the periphery in patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Clinical ophthalmology. 2015;9:1467–1474. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S89371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wegscheider E, Preising MN, Lorenz B. Fundus autofluorescence in carriers of X-linked recessive retinitis pigmentosa associated with mutations in RPGR, and correlation with electrophysiological and psychophysical data. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242(6):501–511. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0891-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobson SG, Yagasaki K, Feuer WJ, Román AJ. Interocular asymmetry of visual function in heterozygotes of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Exp Eye Res. 1989;48(5):679– 691. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(89)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peachey NS, Fishman GA, Derlacki DJ, Alexander KR. Rod and cone dysfunction in carriers of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(5):677– 685. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trifunovic D, Karali M, Camposampiero D, et al. A high-resolution RNA expression atlas of retinitis pigmentosa genes in human and mouse retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(6):2330–2336. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godara P, Cooper RF, Sergouniotis PI, et al. Assessing retinal structure in complete congenital stationary night blindness and Oguchi disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6):987– 1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beltran WA, Acland GM, Aguirre GD. Age-dependent disease expression determines remodeling of the retinal mosaic in carriers of RPGR exon ORF15 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(8):3985–3995. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aguirre GD, Yashar BM, John SK, et al. Retinal histopathology of an XLRP carrier with a mutation in the RPGR exon ORF15. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75(4):431– 443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adamian M, Pawlyk BS, Hong DH, Berson EL. Rod and cone opsin mislocalization in an autopsy eye from a carrier of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa with a gly436Asp mutation in the RPGR gene. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2006;142(3):515– 518. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acton JH, Greenberg JP, Greenstein VC, et al. Evaluation of multimodal imaging in carriers of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Exp Eye Res. 2013;113:41– 48. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuten WS, Tiruveedhula P, Roorda A. Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope-based microperimetry. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89(5):563–574. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182512b98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Q, Tuten WS, Lujan BJ, et al. Adaptive optics microperimetry and OCT images show preserved function and recovery of cone visibility in macular telangiectasia type 2 retinal lesions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):778–786. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bregnhøj J, Al-Hamdani S, Sander B, Larsen M, Schatz P. Reappearance of the tapetal-like reflex after prolonged dark adaptation in a female carrier of RPGR ORF15 X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vision. 2014;20:852–863. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heckenlively J, Weleber R. X-linked recessive cone dystrophy with tapetal-like sheen: A newly recognized entity with Mizuo-Nakamura phenomenon. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1986;104(9):1322–1328. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210076029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Jong P, Zrenner E, van Meel G, Keunen J, van Norren D. Mizuo phenomenon in X-linked retinoschisis: Pathogenesis of the Mizuo phenomenon. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1991;109(8):1104–1108. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080080064029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carroll J, Rossi EA, Porter J, et al. Deletion of the X-linked opsin gene array locus control region (LCR) results in disruption of the cone mosaic. Vision Research. 2010;50(19):1989– 1999. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossi EA, Achtman RL, Guidon A, et al. Visual function and cortical organization in carriers of blue cone monochromacy. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vajaranant TS, Fishman GA, Szlyk JP, et al. Detection of mosaic retinal dysfunction in choroideremia carriers electroretinographic and psychophysical testing. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(4):723– 729. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confocal and non-confocal split-detection AOSLO images depicting cone and rod outer segments and cone inner segments, respectively from an unaffected individual (left, MM_0136) and a carrier (right, MM_0048). Cones were confirmed as such with the aid of the non-confocal image and are marked with turquoise dots. Rod photoreceptors occupying the space between cones are marked with yellow dots. The pixel intensity for all marked photoreceptors was measured on the confocal image using ImageJ and their normalized histogram is plotted below. Approximate location is 2° away from the fovea for both subjects, with all images being 55μm across.

Carriers MM_0037 (top row) and MM_0039 (middle row) imaged 19 weeks apart and MM_0048 (bottom row) imaged 42 weeks apart using confocal AOSLO showing cone and rod outer segments. Scale bars are 100μm.