Abstract

Purpose

Older adults experience impaired driving performance, and modify their driving habits, including limiting amount and spatial extent of travel. Alzheimer disease (AD)-related pathology, as well as spatial navigation difficulties, may influence driving performance and driving behaviors in clinically normal (CN) older adults. We examined whether AD biomarkers (cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of Aβ42, tau and ptau181) were associated with lower self-reported spatial navigation abilities, and whether navigation abilities mediated the relationship of AD biomarkers with driving performance and extent.

Methods

CN older adults (n=112; aged 65+) completed an on-road driving test, the Santa Barbara Sense of Direction scale (self-report measure of spatial navigation ability), and the Driving Habits Questionnaire for an estimate of driving extent (composite of driving exposure and driving space). All participants had a lumbar puncture to obtain CSF.

Results

CSF Aβ42, but not tau or ptau181, was associated with self-reported navigation ability. Lower self-reported navigation was associated with reduced driving extent, but not driving errors. Self-reported navigation mediated the relationship between CSF Aβ42 and driving extent.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that cerebral amyloid deposition is associated with lower perceived ability to navigate the environment, which may lead older adults with AD pathology to limit their driving extent.

Keywords: driving space, preclinical Alzheimer disease, amyloid deposition, on-road driving test

Introduction

Older adults commonly report driving as important for maintaining autonomy1. However, older adults are also more likely to cease driving or reduce amount and spatial extent of everyday driving2. Older adults who have ceased driving exhibit declines in physical, social, and cognitive functioning compared to active older adult drivers3. Additionally, older age is associated with worse driving performance, and an increased risk of crashes and injuries per mile drivene.g.,4,5. Understanding factors contributing to altered everyday driving behaviors and lower driving performance is important for developing interventions to minimize potential negative outcomes.

Existing research suggests impaired driving in Alzheimer disease (AD), and potentially compromised driving performance in mild cognitive impairmente.g.,6,7. Thus, presence of significant AD neuropathology in clinically normal older adults (i.e., preclinical AD) may also influence driving in older adults. Neurofibrillary tangles and cerebral amyloid deposition, two pathological hallmarks of the disease, have been found in clinically normal older adults at autopsy8. Such findings have been instrumental in elucidating presence of a preclinical stage of AD. Currently, several biomarkers exist for detecting amyloid and tau deposition ante-mortem. Reduced cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ42 are associated with formation of amyloid plaques. Increased CSF tau is a marker of neuronal injury and, in AD, is associated with the aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau into neurofibrillary tangles9. Recent work by our group demonstrated that AD biomarkers were cross-sectionally associated with errors during an on-road driving test in clinically normal older adults10. Additionally, baseline AD biomarker levels were found to predict longitudinal decline in driving performance, although not changes in self-reported everyday driving behaviors11.

There is also a relatively extensive literature examining cognitive factors that may contribute to impaired driving in older adults12. Prior investigations have observed modest associations between driving performance and cognitive domains such as processing speed, memory, visuospatial skills and executive functioning12. Additionally, existing work has demonstrated that impaired processing speed and visuospatial abilities are associated with increased likelihood of clinically normal older adults limiting or ceasing drivinge.g.,13,14. However, there is still a lack of consensus regarding which cognitive domains are optimal for predicting driving performance or self-regulation of everyday driving behavior.

Spatial navigation may be particularly relevant for understanding changes in driving. Navigating an environment is a complex, multi-componential skill that allows one to travel to familiar and novel destinations. Errors in driving performance may arise due to actual or perceived need to direct more attention to finding one’s way in the environment. Associations have been observed between driving performance and some component processes of spatial navigation, such as spatial planning on 2D computerized mazes and visual attention to details in scenes potentially encountered when driving14–16. Difficulty with spatial orientation while driving a learned route has also been observed in older adults17. Furthermore, a substantial proportion of older adult drivers report difficulty navigating in unfamiliar places18. Finally, existing research indicates that self-reported navigation problems are associated with avoidance of unfamiliar areas19 and restricted driving space20.

Importantly, preclinical AD has also been associated with impaired spatial navigation abilities21. However, the relationships between preclinical AD, spatial navigation abilities, and driving have not been examined. Thus, the current study examined whether preclinical AD-related difficulties in spatial navigation influence driving performance and everyday driving behaviors. We hypothesized that reduced CSF Aβ42 and increased CSF tau would be associated with lower spatial navigation abilities. In turn, lower spatial navigation abilities would be related to lower driving performance, and greater restrictions in driving extent (i.e., driving exposure and driving space). Furthermore, we hypothesized that these associations would be present after controlling for other cognitive abilities previously associated with driving performance and everyday driving behaviors.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=112; see Table 1) were enrolled in a longitudinal study on preclinical AD and driving performance at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis10,11 and screened for major medical conditions (i.e., Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, stroke, seizure disorder, head injury). Participants were screened for dementia using the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale22 (CDR). All participants were clinically normal (CDR=0), aged 65+, possessed a valid driver’s license, and reported driving at least one time/week at baseline. Participants included are a subsample from prior reports who had all relevant data and passed screening criteria. Participants consented to participation in accordance with Washington University Human Research Protection Office guidelines.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| N | 112 |

| Gender, M/F (%F) | 52/60 (54%) |

| APOE genotype, ε4+/ε4− (%ε4+) | 33/79 (29%) |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 73 (5) |

| Age range, years | 65–88 |

| Education, mean years (SD) | 16 (3) |

| Education range, years | 12–20 |

| Health composite, mean (SD) | 1.08 (.94) |

CSF collection and processing

CSF was obtained by experienced neurologists via standard lumbar puncture (LP) using a 22-gauge Sprotte spinal needle to draw 20–30 mL of CSF at 8:00am following overnight fast. CSF samples were gently inverted to avoid possible gradient effects, centrifuged at low speed and frozen at −84°C after aliquoting into polypropylene tubes. All biomarker assays included a common reference standard, within-plate sample randomization and strict standardized protocol adherence. Samples were re-analyzed if coefficients of variability exceeded 25% (per Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative criteria), or if the pooled common CSF sample yielded widely discrepant values. CSF Aβ42, tau and ptau181 were obtained using sensitive and quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbant assays (ELISA; INNOTEST, Fujirebio [formerly Innogenetics], Ghent, Belgium). The LP was within 2 years (mean=.45 years (SD=.62)) of the testing session for this study.

APOE genotyping

APOE genotyping was collected as described previously23. TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems) for both rs429358 (ABI#C_3084793_20) and rs7412 (ABI#C_904973_10) were used for APOE genotyping. Allele calling was performed using the allelic discrimination analysis module of ABI Sequence Detection Software. Positive controls for each of six possible APOE genotypes were also included on the genotyping plate. Samples were genotyped with the Illumina 610 or the Omniexpress chip and underwent quality control. Individuals were classified as ε4+ (44, 34, 24) or ε4− (33, 23, 22).

Driving test

Participants completed the 12-mile modified Washington University Road Test (mWURT), which takes about an hour to complete24. The course begins in a closed parking lot so that participants become familiar with the study car (i.e., 4-door sedan). It proceeds to a public in-traffic route, which includes left- and right-hand turns, multi-way intersections, and lane merges. The participant drives the mWURT as directed by an examiner in the front seat. The examiner can take control of the wheel, and the vehicle is outfitted with a second, passenger-side brake so that the examiner can apply the brake. The Record of Driving Errors (RODE) was used to obtain total number of driving errors24. Types of driving errors included operational (e.g., signals, steering, pedals), tactical (e.g., stopping, speed, yielding), or information-processing (e.g., attention, decision-making, memory). Research indicates strong interrater reliability for total operational errors, total tactical errors and total information-processing errors (ICC’s>.84)25. In terms of validity, a version of the driving test has been shown to correlate with naturalistic driving measures26. Two examiners scored errors over the course of this study, and were blinded to biomarker, clinical, and psychometric results. Qualitative ratings of pass, marginal and fail were also assigned, with five participants receiving a fail rating. The current study included all participants so as not to artificially restrict the range of error scores.

Driving extent

Driving extent was measured using items from the Driving Habits Questionnaire27 (DHQ), which is a 34-item self-report questionnaire to assess driving behaviors in older adults. A composite of multiple items was created to have a more robust estimate of driving extent. One set of items examined driving space, and required yes/no responses to whether the individual has driven in their neighborhood, beyond their neighborhood, to neighboring towns, to more distant towns, out of the state, and out of the region. Each item was scored as 1 or 0. The scores were summed across items and standardized using a z-transformation. The second set of items examined driving exposure, and required reporting total number of places, trips and miles traveled during a typical week. The standardized driving extent composite was created as the average of the z-scores of the: a) sum of yes/no items, and b) number of places, trips, and miles traveled during a typical week. Lower scores represented more restricted driving extent.

Self-reported navigation

The Santa Barbara Sense of Direction28 (SBSOD), a 15-item questionnaire, was used to assess self-reported spatial navigation abilities. Participants responded on a scale of 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). The fifteen items were averaged to create a total score with lower scores representing lower self-rated navigation. SBSDO has demonstrated adequate reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.88) and high test-retest reliability (r=0.91)28. Additionally, a series of experiments established the validity of the SBSOD across a variety of navigation-related tasks. SBSOD score was correlated with accuracy of identifying landmark locations in a large-scale environment, learning the layout of a new environment via actual experience, and with learning a new environment via video or virtual reality28. Collectively, results from these validity studies indicate that the SBSOD is strongly related to objective measures of spatial navigation skills.

Cognitive performance

A cognitive composite was created based on measures of episodic memory, visuomotor speed, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability. Free recall from the Selective Reminding Task29 was used to estimate of episodic memory. Visuomotor speed was estimated using Trailmaking Test, Part A30. Trailmaking Test, Part B30 served to estimate executive functioning. Finally, Block Design from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale31 (n=95) or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III32 (n=16) was used to estimate visuospatial ability. In order to have an estimate of each individual’s relative ranking on Block Design for the total sample, raw scores on respective versions obtained within each subsample were standardized using a z-transformation. Scores on each individual task were standardized, and the composite score was created by averaging standardized scores. Trailmaking Test, Part B data were missing for four individuals, and the composite score was based on data from the remaining three tasks.

Data analyses

Covariates

Age, gender, education, APOE status, and a health composite were control variables in analyses. Rater of the driving errors was an additional covariate in analyses of driving performance. The health composite was the sum of the presence or history of: hypertension, diabetes, depression, and heart problems (total=0–4). APOE groups did not differ on any variable (ps>.132), except for CSF Aβ42 (t(110)=4.619, p<.001).

Outliers

Univariate outliers were defined as values ≥ 3 STD from the mean. Analyses were conducted with and without outliers. Results were the same with outliers removed except when noted in results.

CSF assay drift

Recent research has observed significant drift in CSF levels over time as measured by INNOTEST33. This study included CSF samples collected over 3.5 years. Thus, assay kit number was added as a covariate to determine the degree to which results were impacted by drift. Results were unchanged with assay kit number included as a covariate. Results without this variable are presented in the results.

Statistical analyses

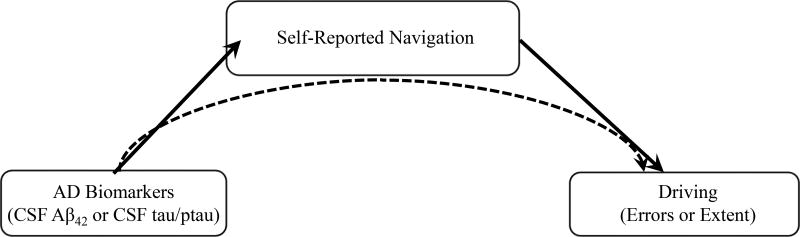

A mediation model was specified with an AD biomarker (i.e., CSF Aβ42 or CSF tau/ptau181) as the predictor variable, self-reported navigation as mediator, and driving errors or driving extent composite as outcome variable (see Figure 1 for hypothesized models). Both the mediator and the outcome variable were adjusted for covariates. CSF Aβ42 and CSF tau/ptau181 were continuous variables. Analyses to determine total, direct and indirect effects were conducted using the PROCESS macro34 in SPSS 23, which implements a regression-based approach to estimate effects in conjunction with bootstrapping techniques.

Figure 1.

Path model depicting hypothesized mediation models. The solid line from AD biomarkers to self-reported navigation represents the hypotheses that lower levels of CSF Aβ42 and higher levels of CSF tau/ptau181 would be associated with lower self-reported navigation. The solid line from self-reported navigation to driving reflects hypotheses that lower self-reported navigation would be associated with more driving errors and more restricted driving extent. The dashed line from AD biomarkers to driving reflects the hypotheses that self-reported spatial navigation would mediate the relationships between AD biomarkers and driving variables.

The total effect represents the association of the predictor with the outcome and includes both direct and indirect effects. The direct effects indicate the degree of association between a) the predictor variable and the mediator; b) the mediator and the outcome variable controlling for the predictor variable; and c) the predictor variable and the outcome variable controlling for the mediator. The indirect effect represents the degree to which the predictor variable influences the outcome variable via the mediator. Mediation analyses (i.e., examination of the indirect effects) were only examined when the predictor and outcome variable were significantly related to the mediator (i.e., self-reported navigation). Based on current recommendations, a significant relationship between the predictor variable and the outcome variable was not required35,36. The significance of the indirect effect was examined using 10,000 bootstrapping samples and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Significance is indicated when the CI intervals do not include zero.

The cognitive composite was added as an additional covariate when the indirect effect was found to be significant to examine whether indirect effects of self-reported navigation were independent of effects of other cognitive abilities.

Results

CSF Aβ42

Both total effect and direct effects of CSF Aβ42 were significant for driving errors (total: β=−.226, SE=.085, t=−2.664, p=.009; direct: β=−.243, SE=.087, t=−2.791, p=.006). Individuals with lower levels of CSF Aβ42 made more driving errors. This is generally consistent with our prior cross-sectional finding with the larger sample10. There was a significant direct effect of CSF Aβ42 on self-reported navigation (β=.237, SE=.102, t=2.330, p=.022). Individuals with lower levels of CSF Aβ42 reported lower navigational skills. Importantly, the direct effect of self-reported navigation on driving errors was not significant (β=.072, SE=.082, t=.881, p=.380). Given this lack of an association between mediator and outcome, mediation was not examined.

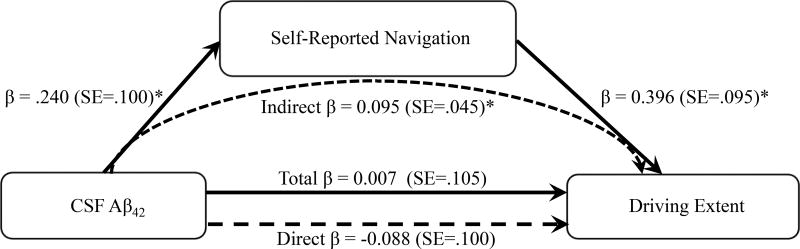

Results of the mediation model for driving extent are depicted in Figure 2. Neither the total nor the direct effect of CSF Aβ42 on the driving extent composite was significant (total: β=.007, SE=.105, t=.067, p=.947; direct: β=−.088, SE=.100, t=−.881, p=.381). There was a significant direct effect of CSF Aβ42 on self-reported navigation (β=.240, SE=.100, t=2.393, p=.019). Additionally, the direct effect of self-reported navigation on driving extent was significant (β=.396, SE=.095, t=4.178, p=.001). Individuals with lower self-reported navigation had lower scores on the driving extent composite. There was a significant indirect effect of CSF Aβ42 on the driving extent composite through self-reported navigation (β=.095, SE=.045; 95%CI: .025 – .206). The indirect effect remained significant when additionally controlling for the cognitive composite (β=.084, SE=.045; 95%CI: .0153–.204).

Figure 2.

Path model of the relationships among CSF Aβ42, self-reported spatial navigation ability and driving extent. Standardized path coefficients are presented. *p<.05.

CSF tau and ptau181

Neither the total nor the direct effect of CSF tau was significant for driving errors (total: β=.082, SE=.079, t=1.037, p=.302; direct: β=.081, SE=.081, t=1.002, p=.319). This is generally consistent with our prior cross-sectional finding with the larger sample10. Similarly, neither the total nor the direct effect of CSF tau was significant for the driving extent composite (total: β=.123, SE=.094, t=1.312, p=192; direct: β=.058, SE=.090, t=.643, p=.522). Importantly, the direct effect of CSF tau on self-reported navigation was not significant (β=.179, SE=.091, t=1.959, p=.053; with outliers removed: β=.138, SE=.108, t=1.277, p=.205). Results were similar for ptau181, as there was no association with driving errors (total: β=.071, SE=.079, t=.898, p=.371; direct: β=.069, SE=.080, t=.863, p=.390), or with the driving extent composite (total: β=.135, SE=.093, t=1.455, p=.145; direct: β=.075, SE=.089, t=.846, p=.400). The direct effect of CSF ptau181 on self-reported navigation was also not significant (β=.166, SE=.091, t=1.825, p=.071; with outliers removed: β=.094, SE=.113, t=.829, p=.409). Given the lack of associations between these predictors (CSF tau and ptau181) and the mediator, mediation was not examined.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that lower CSF levels of Aβ42 (a marker of amyloid plaques in AD) were associated with lower self-reported driving extent via self-reported navigation abilities. This finding suggests that perceptions about the ability to navigate the environment may contribute to decisions about reducing driving extent for clinically normal older adults with amyloid deposition. The lower self-report of spatial navigation skills with increasing amyloid deposition may to some degree reflect the ability of these individuals to acquire spatial knowledge and orient within environments. That is, scores on the SBSOD scale have been associated with the ability to learn spatial layouts of large-scale environments, and to update one’s location during self-motion28. Furthermore, a previous study observed that clinically normal individuals with low levels of CSF Aβ42 had greater difficulty on an objective measure of spatial navigation ability that required formation of a mental map of a novel environment23. In addition, some correspondence between findings based on self-reported driving space and those based on directly measuring driving area has been observed22. Collectively, these findings suggest that presence of amyloid plaques may impair the ability of clinically normal individuals to effectively navigate, and that a self-report measure of spatial navigation may be useful for predicting relevant functional outcomes such as everyday driving behaviors.

The indirect effect of CSF Aβ42 on driving extent via self-reported spatial navigation remained significant when additionally controlling for the cognitive composite. This suggests a unique mediating role for large-scale spatial navigation skills above and beyond other cognitive functions in the preclinical AD stage. In the current study, both self-reported spatial navigation and the cognitive composite (partial correlation r=.267, p=.005) were associated with aspects of everyday driving behavior in older adults, which is generally consistent with existing literature13,14,21,22. However, there was not a significant association between CSF Aβ42 and the cognitive composite (partial correlation r=.119, p=.224). In fact, a recent meta-analysis revealed significant, but small, associations of amyloid deposition with episodic memory and executive function, but no significant associations for working memory, processing speed or visuospatial skills37. Furthermore, one previous study observed that the ability to form a mental map of an environment, but not episodic memory, discriminated between clinically normal individuals with and without preclinical AD23. These findings highlight the potential utility of particularly focusing on spatial navigation skills to understand the impact of cognitive deficits in the preclinical AD phase on relevant functional outcomes, such as every driving behaviors.

In contrast to CSF Aβ42, CSF tau and ptau181 were not significantly related to self-reported spatial navigation ability. This finding is similar to a prior report of a significant association between CSF Aβ42 and the ability to form a mental map of an environment, but no such association for CSF tau23. The reason for the discrepancy for CSF Aβ42 relative to CSF tau and ptau181 is uncertain. Although clinically normal individuals may possess both neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques8, previous findings indicate that changes in CSF Aβ42 may precede changes in CSF tau and, therefore, represent an earlier indicator of AD pathology in clinically normal individuals38. Thus, CSF Aβ42 may be more related to cognitive deficits in earlier stages, whereas CSF tau and ptau181 may be more associated with decline as the disease progresses. Consistent with this speculation, a previous study demonstrated that CSF levels of Aβ42, but not tau, were related to baseline measures of attention, whereas CSF levels of tau, but not Aβ42, were associated with longitudinal declines in attention and memory over an 8-year period39. Subsequent longitudinal research with a larger sample is needed to determine the relationship of each AD biomarker with changes in spatial navigation across the pathological stages of the disease, both preclinical and symptomatic.

Notably, self-reported spatial navigation was not significantly associated with on-road driving errors, and thus could not serve as a mediator of CSF Aβ42 effects. This suggests that perceptions of navigational skills may be relatively more predictive of self-regulation of everyday driving behaviors compared to actual driving performance in preclinical AD. However, there is a relative dearth of studies examining relationships between objective measures of navigating through large-scale environmental spaces and driving performance. Existing work only incorporates some potential component processes in a limited way, such as spatial planning in 2D computerized mazes and visual attention to details in driving-related scenes15–17; but see 18. Thus, it is still conceivable that direct measures of specific spatial navigational skills may evidence more robust associations with actual driving problems. Additionally, road tests that capture more strategic or self-directed route driving and wayfinding may evidence stronger associations with navigational tests.

One limitation of this study is the cross-sectional design, and longitudinal follow-up is an important next step for examining whether spatial navigation predicts reductions in driving extent over time during preclinical AD. Future work should also determine whether observed patterns differ based on APOE status. Additionally, the sample size could have limited the power for detecting small, but relevant effects. As driving extent and spatial navigation abilities were both assessed using self-report measures, subjective cognitive impairment may have contributed to current findings. Although the self-report measure of spatial navigation abilities has been found to be associated with observed measures of navigation skills28, future research could examine spatial navigation abilities using more objective measures. A more direct measure of restricted driving space that captures day-to-day driving in older adults would also improve upon this study. For example, global positioning data acquisition system devices allowing measurement of variables such as driving areas, number of trips taken, and number of miles driven could more directly capture everyday driving behaviors40. Finally, this study did not incorporate other individual differences that may contribute to driving performance or extent such as vision, motor functioning, social network size or financial resources.

In conclusion, current findings suggest that presence of amyloid plaques as evidenced by low levels of CSF Aβ42 is associated with lower perceived navigation in clinically normal older adults, which limits the extent to which they drive in their environment. Future research should examine the degree to which spatial navigation skills and perceptions of such skills may influence eventual driving cessation. Future investigations should also examine ways to improve spatial navigation abilities and/or confidence in navigating in clinically normal older adults, particularly those with amyloid plaques, so as to maintain their driving autonomy.

Table 2.

Demographic Statistics.

| Variable | Mean | STD | Range | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF Aβ42, | 827.11 | 298.71 | 206.16–1634.38 | .21 | −.44 |

| CSF Tau | 351.51 | 205.39 | 103.91–1187.75 | 1.93 | 4.31 |

| CSF Ptau181 | 63.74 | 31.31 | 20.86–186.18 | 1.64 | 2.75 |

| Santa Barbara Sense of Direction | 5.10 | 1.06 | 2.33–7.00 | −.45 | −.30 |

| Driving Errors | 8.53 | 4.98 | 0–25 | .66 | .54 |

| Driving Extent | 0.00 | .69 | −1.97–1.78 | −.55 | .79 |

| Cognitive Composite | 0.00 | .66 | −2.05–1.62 | −.58 | .85 |

| Selective Reminding Task | 32.32 | 5.83 | 15–48 | −.41 | .54 |

| Trailmaking Test, Part A | 28.95 | 8.62 | 14–59 | 1.16 | 1.99 |

| Trailmaking Test, Part B | 71.81 | 28.29 | 34–180 | 2.01 | 5.22 |

| WAIS/WAISIII Block Design | 0.00 | 1.00 | −2.32–1.90 | −.050 | −.647 |

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging [R01AG043434, R01AG43434-03S1, P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276] and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer Research Initiative of the Washington University Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC). The authors thank the participants, investigators, and staff of the Knight ADRC Clinical Core for participant assessments, Genetics Core for APOE genotyping, and the Biomarker Core for CSF analysis.

Dr. Fagan reports being on the scientific advisory boards of IBL International and Roche, and is a consultant for AbbVie and Novartis.

Neither Dr. Morris nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Dr. Morris is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs from Eli Lilly and Company, Biogen, and Janssen. Dr. Morris serves as a consultant for Lilly USA. He receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and is funded by NIH grants # P50AG005681; P01AG003991; P01AG026276 and UF01AG032438.

References

- 1.Adler G, Rottunda S. Older adults’ perspectivwes on driving cessation. J Aging Stud. 2006;20:227–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unsworth CA, Wells Y, Browning C, Thomas SA, Kendig H. To continue, modify or relinquish driving: Findings from a longitudinal study of healthy ageing. Gerontology. 2007;53:423–31. doi: 10.1159/000111489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chihuri S, Mielenz TJ, DiMaggio CJ, Betz ME, DiGuiseppi C, Jones VC, Li G. Driving cessation and health outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:332–41. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doroudgar S, Chuang HM, Perry PJ, Thomas K, Bohnert K, Canedo J. Driving performance comparing older versus younger drivers. Traffic Inj Prev. 2017;18:41–46. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2016.1194980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute. Fatality Ffacts: Older drivers [on-line] Insurance Institute for Highway Safety; Arlington, VA: [Accessed July 17, 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anstey KJ, Eramudugolla R, Chopra S, Price J, Wood J. Assessment of driving safety in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. J Alz Dis. 2017;57:1197–1205. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chee JN, Rapoport MJ, Molnar F, Herrmann N, O'Neill D, Marottoli R, Mitchell S, Tant M, Dow J, Ayotte D, Lanctôt KL, McFadden R, Taylor JP, Donaghy PC, Olsen K, Classen S, Elzohairy Y, Carr DB. Update on the risk of motor vehicle collision or driving impairment with dementia: A aollaborative international systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25:1376–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and "preclinical" Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:358–68. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:413–7. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roe CM, Barco PP, Head D, Ghoshal N, Selsor N, Babulal GM, Fierberg R, Vernon EK, Shulman N, Johnson A, Fague S, Xiong C, Grant EA, Campbell A, Ott BR, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Carr DB, Morris JC. Amyloid imaging, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers predict driving performance among cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31:69–72. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roe CM, Babulal GM, Head D, Stout SH, Vernon EK, Ghoshal N, Garland B, Barco PP, Williams MM, Johnson A, Fierberg R, Fague MS, Xiong C, Mormino E, Grant EA, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ott BR, Carr DB, Morris JC. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and longitudinal driving decline. Alzheimers Dement: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2017;3:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathias JL, Lucas LK. Cognitive predictors of unsafe driving in older drivers: A meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:637–653. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209009119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keay L, Munoz B, Turano KA, Hassan SE, Munro CA, Duncan DD, Baldwin K, Jasti S, Gower EW, West SK. Visual and cognitive deficits predict stopping or restricting driving: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Driving Study (SEEDS) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:107–13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown LB, Stern RA, Cahn-Weiner DA, Rogers B, Messer MA, Lannon MC, Maxwell C, Souza T, White T, Ott BR. Driving scenes test of the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) and on-road driving performance in aging and very mild dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;20:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ott BR, Heindel WC, Whelihan WM, Caron MD, Piatt AL, DiCarlo MA. Maze test performance and reported driving ability in early dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16:151–155. doi: 10.1177/0891988703255688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ott BR, Festa EK, Amick MM, Grace J, Davis JD, Heindel WC. Computerized maze navigation and on-road performance by drivers with dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21:18–25. doi: 10.1177/0891988707311031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Ridder SN, Elieff C, Diesch A, Gershenson C, Pick HL., Jr Staying oriented while driving; Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 46th Annual Meeting; Santa Monica, CA. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burns PC. Navigation and the mobility of older drivers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54:S49–55. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryden KJ, Charlton JL, Oxley JA, Lowndes GJ. Self-reported wayfinding ability of older drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;59:277–82. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turano KA, Munoz B, Hassan SE, Duncan DD, Gower EW, Roche KB, Keay L, Munro CA, West SK. Poor sense of direction is associated with constricted driving space in older drivers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:348–55. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allison SL, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Head D. Spatial navigation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:77–90. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Nowotny P, Bales K, Pickering EH, Mayo K, Bertelsen S, Hinrichs A, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Cerebrospinal fluid APOE levels: An endophenotype for genetic studies for Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4558–71. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barco PB, Carr DB, Rutkoski K, Xiong C, Roe CM. Interrater reliability of the Record of Driving Errors (RODE) Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69:1–6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2015.013128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barco PP, Carr DB, Rutkoski K, Xiong C, Roe CM. Interrater reliability of the Record of Driving Errors (RODE) Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69:1–6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2015.013128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis JD, Papandonatos GD, Miller LA, Hewitt SD, Festa EK, Heindel WC, Ott BR. Road test and naturalistic driving performance in healthy and cognitively impaired older adults: Does environment matter? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2056–2062. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owsley C, Stalvey B, Wells J, Sloane ME. Older drivers and cataract: Driving habits and crash risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M203–11. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.4.m203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hegarty M, Richardson AE, Montello DR, Lovelace K, Subbiah I. Development of a self-report measure of environmental spatial ability. Intelligence. 2002;30:425–48. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grober E, Buschke H, Crystal H, Bang S, Dresner R. Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology. 1998;38:900–903. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.6.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armitage SG. An analysis of certain psychological tests used for the evaluation of brain injury. Psychol Monographs. 1945;60:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schindler SE, Sutphen CL, Teunissen C, McCue LM, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Mulder SD, Scheltens P, Xiong C, Fagan AM. Upward drift in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid β 42 assay values for more than 10 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets VA. Comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rucker DD, Preacher KJ, Tormala ZL, Petty RE. Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social Pers Psych Compass. 2011;5/6:359–371. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedden T, Oh H, Younger AP, Patel TA. Meta-analysis of amyloid-cognition relations in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2013;80:1341–1348. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828ab35d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigan SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MC, Trojanowski JQ. Update on hypothetical model of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aschenbrenner AJ, Balota DA, Fagan AM, Duchek JM, Benzinger TL, Morris JC. Alzheimer disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers moderate baseline differences and predict longitudinal change in attentional control and episodic memory composites in the adult children study. JINS. 2015;21:573–83. doi: 10.1017/S1355617715000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babulal GM, Traub CM, Webb M, Stout SH, Addison A, Carr DB, Ott BR, Morris JC, Roe CM. Creating a driving profile for older adults using GPS devices and naturalistic driving methodology. F100 Research. 2006;5:2376. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.9608.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]