Abstract

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a durable and reliable procedure to alleviate pain and improve joint function. However, failures related to flexion instability sometimes occur. The goal of this study was to define biological differences between tissues from patients with and without flexion instability of the knee after TKA. Human knee joint capsule tissues were collected at the time of primary or revision TKAs and analyzed by RT-qPCR and RNA-seq, revealing novel patterns of differential gene expression between the two groups. Interestingly, genes related to collagen production and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation were higher in samples from patients with flexion instability. Partitioned clustering analyses further emphasized differential gene expression patterns between sample types that may help guide clinical interpretations of this complication. Future efforts to disentangle the effects of physical and biological (e.g., transcriptomic modifications) risk factors will aid in further characterizing and avoiding flexion instability after TKA.

Keywords: total knee arthroplasty, flexion instability, revision total knee arthroplasty, cell biology, molecular genetics

INTRODUCTION

Instability after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the most common modes of failure requiring revision arthroplasty [1, 2]. Instability cases account for approximately 30% of revision TKAs performed in the US [3, 4] and other developed countries [5]. Though improvements in implant design and surgical technique have decreased the risk of instability, the projected increase in number of primary TKAs performed will continue to burden surgeons and health care systems [6-9]. Instability can be categorized as global instability, flexion instability, extension instability, and recurvatum [1, 10, 11]. Flexion instability is a finite diagnosis in which there is a flexion and extension mismatch, resulting in recurrent hemarthroses and a finite constellation of signs and symptoms [10]. Patients with flexion instability after TKA present with symptoms ranging from discomfort and a subjective sense of instability to complete dislocation of their prosthesis [12-14]. Clinical examination can reveal recurrent knee effusions, anterior or medial joint line tenderness, and/or excessive laxity of the collateral ligaments [3, 13, 14]. Radiographic analysis can determine implant positioning and alignment in multiple planes, as well as limb alignment, tibial slope, and flexion gap to determine the severity of instability [1, 10]. However, additional methods (e.g., molecular biomarkers) for characterizing the risk of instability after TKA would be beneficial for the improvement of surgical intervention strategies and long-term patient outcomes.

The failure mechanism for flexion instability after TKA is multifactorial, attributed to biomechanical insufficiencies of native tissues (e.g., ligament injury) and/or direct failure of the implant device [15]. Poor surgical techniques (e.g., undersized femoral component, internal rotation of components, excessive tibial slope, inadequate distal femoral resection, or excessive release of the medial collateral ligament) and/or the host soft-tissue status can lead to mismatched flexion/extension gaps that lead to worsening flexion instability [1, 10, 15, 16]. The varied clinical presentations of flexion instability after TKA suggest pleiotropic and/or patient specific causes (and likely treatment strategies) of this orthopedic problem. However, additional insight into the molecular mechanisms that distinguish TKA instability tissues from normal tissues will yield useful insights regarding similarities among patients with similar symptoms.

Clinically, epidemiologic and retrospective studies have identified risk factors and biomechanical etiologies underlying arthroplasty failure [17], yet limited data exist regarding the relationship of biological mediators regulating this clinical scenario. Furthermore, preoperative variables and demographics alone are of limited use in predicting functional outcomes and pain scores following TKA [18]. Recognizing important biological mediators may help characterize the significance of extracellular matrix remodeling, osteolysis, the post-traumatic inflammatory cascade, and other pathogenic mechanisms involved in the development of flexion instability following TKA.

High-throughput next-generation sequencing tools can provide a basis for identifying differentially expressed genes correlated to flexion instability after TKA. For example, RNA-seq has been used to successfully identify differences in gene expression between normal tissues and tissues affected by numerous musculoskeletal diseases including osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis [19-21]. Identifying gene products that are over-expressed in patients with flexion instability after TKA will provide information regarding genes and biological pathways implicated in the condition. Dysregulation of genes involved in tissue repair and remodeling of the surrounding soft tissue enveloping the knee joint, and/or oxidative stress reactions may negatively alter postoperative healing. Furthermore, highlighting key genes involved in tissue dysfunction may help characterize novel co-morbidities of flexion instability after TKA (e.g., poor joint perfusion, smoking, diabetes) and cell signaling pathways amenable to therapeutic intervention or prophylaxis.

Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their endogenous inhibitors, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs), may be involved in the molecular pathophysiology of flexion instability after TKA. Importantly, MMPs are involved in tissue remodeling, extracellular matrix degradation, and have a prominent role in many musculoskeletal pathologies [19, 22, 23]. For example, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the promoter region of MMP1 has been associated with aseptic loosening of total hip arthroplasty when detected in peripheral blood [24]. Elevated MMP1 expression may also induce excessive tissue degradation of the periprosthetic microenvironment [25], that results in late manifestations of prosthesis malignment. In contrast, increased MMP3 expression may correlate with exposure of synovial tissues to particulate debris [26-28]. Nonetheless, ECM remodeling genes will be important to analyze and monitor in patients with flexion instability after TKA.

The aim of this study was to investigate differential gene expression patterns among synovial capsular tissues collected from normal adults undergoing primary TKAs and patients requiring revision procedures due to flexion instability after TKA. The pathology of flexion instability after TKA is currently defined only by clinical and radiographic parameters, so establishing a biological mechanism for this complication will not only allow refined detection strategies, but also facilitate intervention strategies to prevent and treat the condition.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Patient Enrollment & Tissue Handling

In accordance with our approved IRB protocol (09-000115, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), all patients were identified, verbally informed, and signature-consented prior to enrollment in the study. When possible, patient clinical data were screened and matched based on age (±5 years), gender, and body mass index (BMI) (±5 kg/m2). We collected a total of 32 patient samples (16 primary TKAs [control group] and 16 TKAs revised for flexion instability [experimental group]). At the time of revision surgery, suprapatellar synovial capsular tissue (either control or experimental) were carefully dissected by the operative surgeon using a scalpel. After rinsing with sterile PBS, tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C for further analysis.

RNA Handling

Frozen tissue biopsies were ground into powder by mortar and pestle and homogenized in Qiazol reagent using the TissueLyser LT (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genomic RNA extractions were performed using the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and eluted in 50μL total volume. A NanoDropper (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used to measure RNA concentration and purity. The Mayo Clinic Gene Expression Core (Advanced Genomics Technology Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) also provided an RNA quality assessment (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using RNA integrity number (RIN) as a tool for prioritization of samples for RNA-seq data collection.

RNA-seq data collection was performed by the Gene Expression Core, a division of the Advanced Genomics Technology Center at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Specifically, a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) was used to run 51 bases per read, 6 samples per lane, and paired-end index reads. The RNA Sample Prep Kit v2 library preparation type was specficied for use by the Gene Expression Core, to complete poly-A mRNA purification, cDNA synthesis, sequencing and base-calling as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Using the MAP-RSeq v.1.2.1 workflow, reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) were provided, which includes alignment with Tophat 2.0.6 [29] and normalization with edgeR 2.6.2 [30]. For a larger set of patient samples, reverse transcription and RT-qPCR reactions were performed as described previously [31]. Transcript levels were quantified using the 2-ΔΔCt method and normalized to AKT1 (×100).

Statistical Analyses & Bioinformatics

The final mapped RNA-seq data contained all reads expressed as RPKM estimates (a normalized metric based on the most abundant mRNAs detected in each sample/lane). We selectively prioritized gene expression values above the commonly reported limit of technical detection by HiSeq 2000 (RPKM>0.3). Any detectable fragments that were not mapped to a known messenger RNA were also eliminated. Following average calculations within each group (e.g., pTKA and insTKA), we calculated fold change values between the groups and sorted them by whether their values were “up-regulated” or “down-regulated”. The resulting gene list was further analyzed using the following bioinformatics tools: hierarchical clustering (GeneMania [32], which does not consider statistical rigor), and a second hierarchical clustering method (Pvclust v1.2-2 [33], which does incorporate a statistical algorithms). 100,000 bootstrap replicates were performed for confidence estimation. Statistical significance values were computed by paired t-test and presented as both p<0.05 and p<0.10.

RESULTS

Sampling Scheme

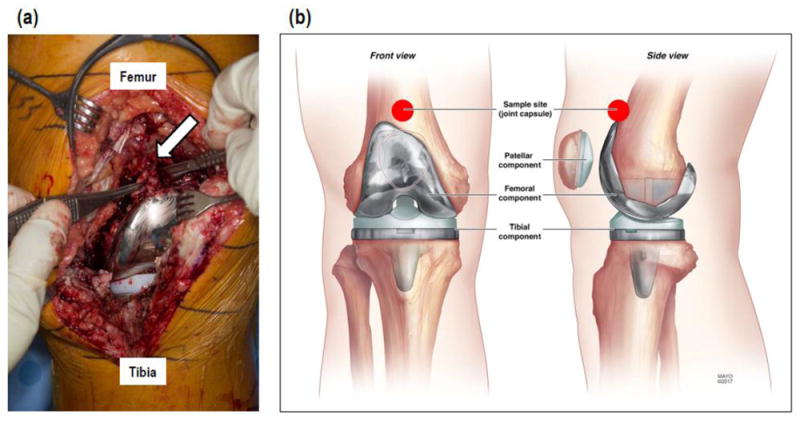

Patients enrolled in this study ranged in age from 29.8 - 76.5 years, body mass indices from 18.8 - 38.6 kg/m2, and 53.1% of patients were female (Table 1). In total, 32 joint capsule tissues were collected from the suprapatellar synovium of individual patients undergoing primary TKA (n=16) and those being revised for flexion instability (n=16) (Figure 1). All 32 samples were analyzed by RT-qPCR, while 6 samples (3 from each group) were analyzed by RNA-seq.

Table 1.

Sampling scheme for qPCR and RNA-seq data collection.

| A)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary TKA | |||

| Sample ID | Age (Years) | Gender | BMI (kg/m2) |

| 1A | 68.5 | F | 24.5 |

| 2A | 70 | M | 24.9 |

| 3A | 68.1 | F | 27.8 |

| 4A | 56.3 | F | 38.1 |

| 8A | 65.7 | F | 41.5 |

| 9A | 56.3 | M | 34.8 |

| 10A | 56.4 | F | 26.9 |

| 11A | 61.4 | F | 38.2 |

| 12A | 62.7 | M | 27.2 |

| 14A | 70 | F | 28.8 |

| 15A | 70.4 | F | 29.2 |

| 16A | 63.5 | M | 38.6 |

| 17A | 65.4 | M | 32.2 |

| 18A | 67 | M | 32.9 |

| 19A | 75.2 | F | 29.8 |

| 20A | 70.1 | M | 37 |

|

| |||

|

B)

| |||

| Instability TKA | |||

| Sample ID | Age (Years) | Gender | BMI (kg/m2) |

| 1B | 62.8 | F | 20.1 |

| 2B | 61.3 | M | 25.9 |

| 3B | 70.4 | F | 36.6 |

| 4B | 29.8 | M | 35.6 |

| 5B | 50.9 | F | 33.7 |

| 6B | 59.8 | M | 36.2 |

| 7B | 72.8 | M | 26.8 |

| 8B | 68.8 | M | 25.6 |

| 9B | 43.4 | F | 26.6 |

| 10B | 52.3 | M | 25.9 |

| 11B | 69.1 | M | 31 |

| 12B | 69 | F | 27.1 |

| 13B | 76.5 | F | 27.1 |

| 14B | 72.7 | F | 27.1 |

| 14B | 67.8 | M | 24.9 |

| 16B | 65.2 | F | 18.8 |

(a) Instability TKA (n=16) and (b) primary TKA (n=16). Bold text indicates samples analyzed for RNA-seq (n=3 for each group).

Figure 1.

(a) Surgical photo and (b) illustration showing anatomic location of tissue sampling.

Distinctiveness of sample types

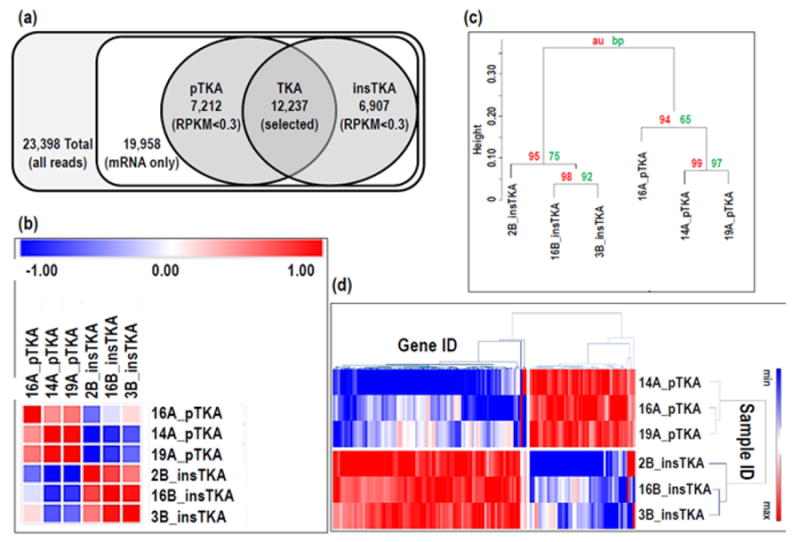

RNA-seq data collection resulted in a total of 23,398 mapped fragments, nearly 20,000 of them are known mRNAs. After pruning these data for poorly detected mRNAs (RPKM<0.3) left nearly 12,000 genes included in downstream analyses (Figure 2a). Hierarchical clustering analysis resulted in two distinct clusters grouped by sample type and highlighting differentially expressed genes (both high and low RPKM values) within each sample type that are common to each group (Figure 2b). Group clusters were well-supported by approximate unbiased p-value estimates (numbers closer to 100 indicate more robust nodes on the dendrogram) and bootstrap proportions. Samples 14A and 19A were nested within the pTKA group in the Pvclust analysis (Figure 2c), whereas samples 19A and 16A formed a sister relationship in the GeneMania analysis (Figure 2d). Overall clustering patterns for samples within the insTKA group were similar among analysis modes (Figures 2b, 2c, 2d).

Figure 2.

(a) RNA-seq pruning strategy, and (b) similarity matrix for all RNA-seq samples included in this study, (c) dendrogram (100,000 replicates), (d) heatmap of all RNA-seq data - pTKA vs insTKA.

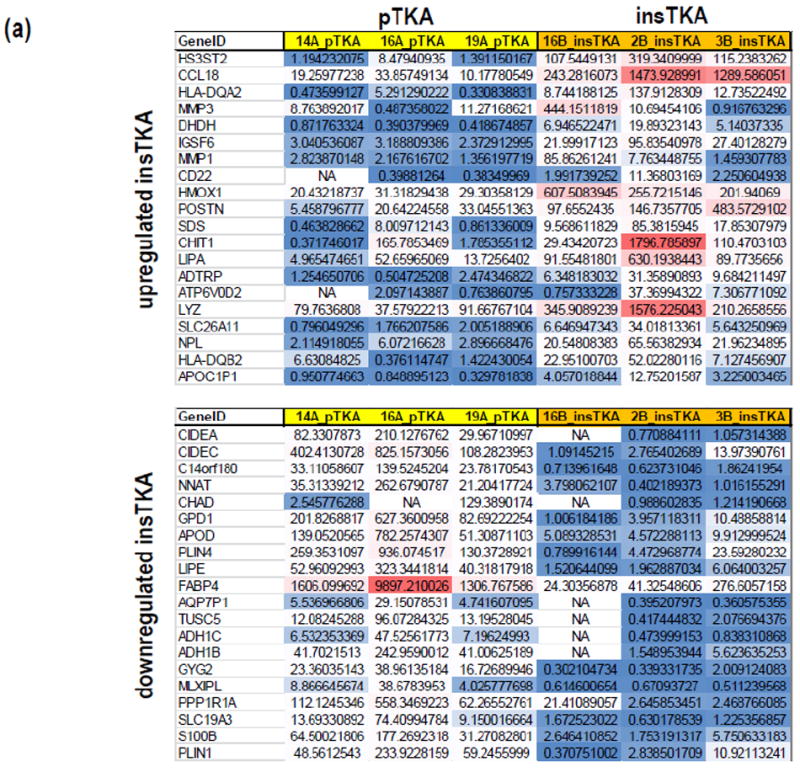

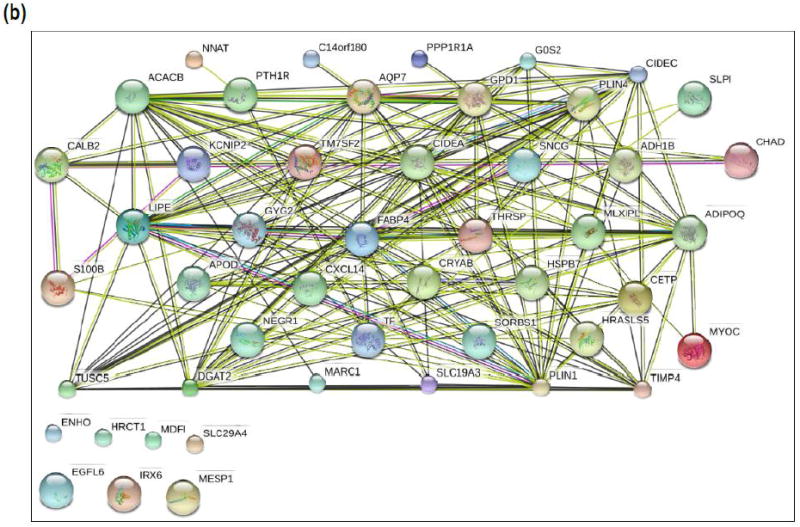

Gene expression profiles of capsular tissue

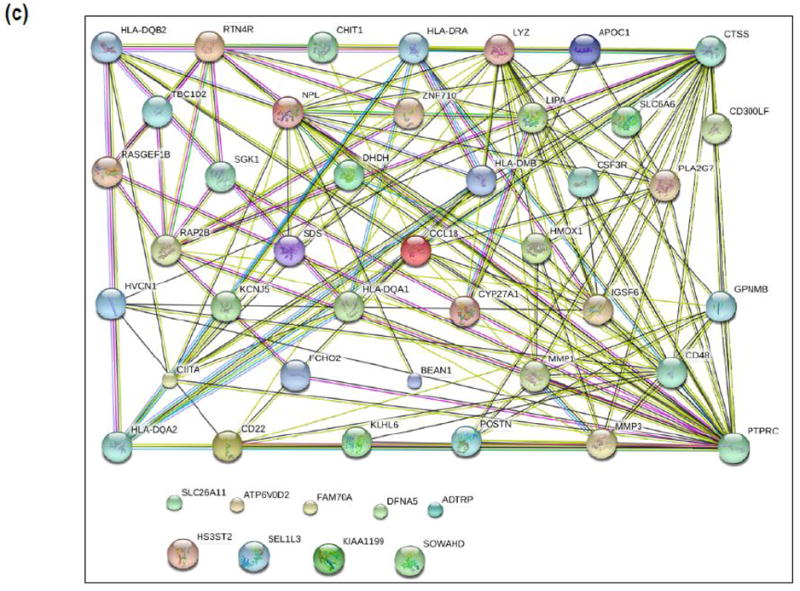

Differential gene expression analysis of the top 20 upregulated genes in tissues from instability TKA patients revealed a list with cell surface markers (e.g., CD22), chemokines (e.g., CCL18), matrix metalloproteinases (e.g., MMP3), and oxygen-related enzymes (e.g., HMOX1) (Figure 3a). Functional protein association networks involving the top 50 genes decreased in insTKA samples compared to controls (pTKA) (Figure 3b), and bottom 50 genes elevated in insTKA samples compared to controls (Figure 3c) revealed highly connected networks of genes with only 7 and 9 genes that remained unincorporated, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Gene expression profiles of capsular tissue, (b) STRING analysis (n=50) of Top Genes Decreased in InsTKA samples compared to controls (pTKA), (c) STRING analysis (n=50) of Top Genes Elevated in InsTKA samples compared to controls.

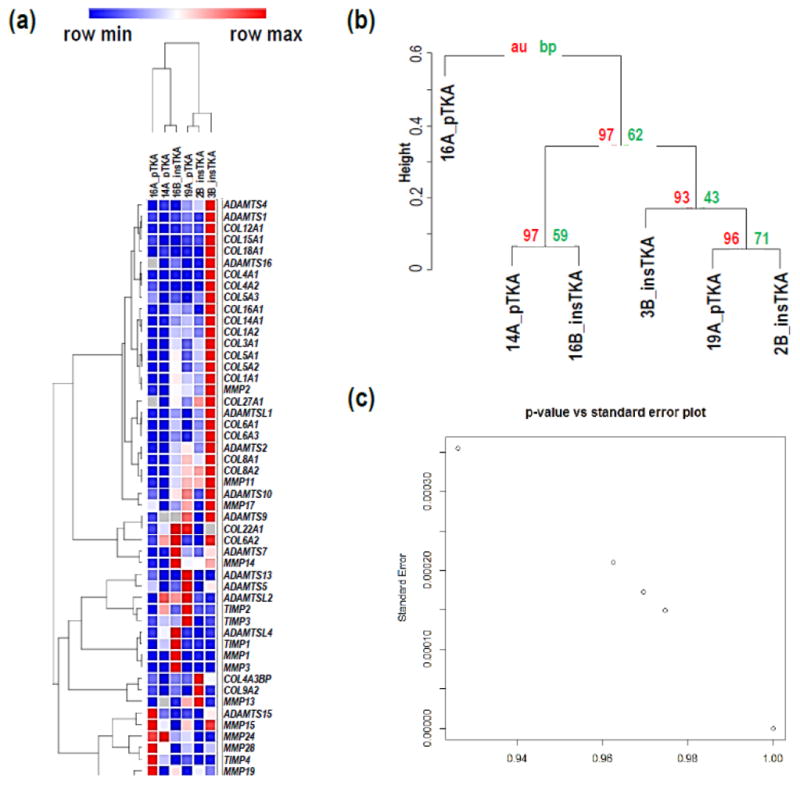

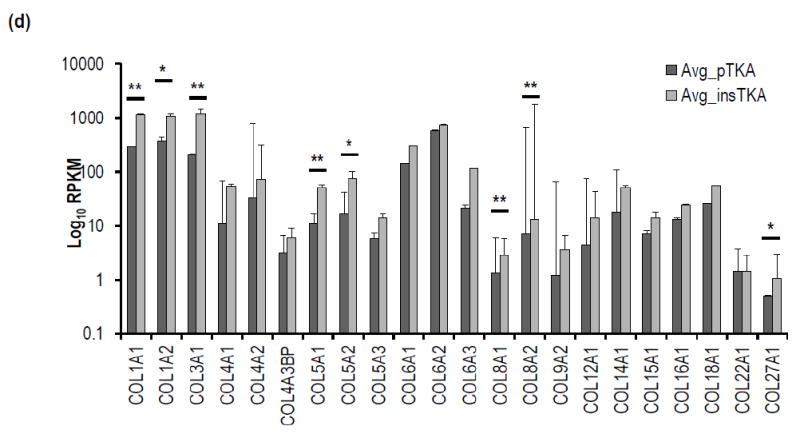

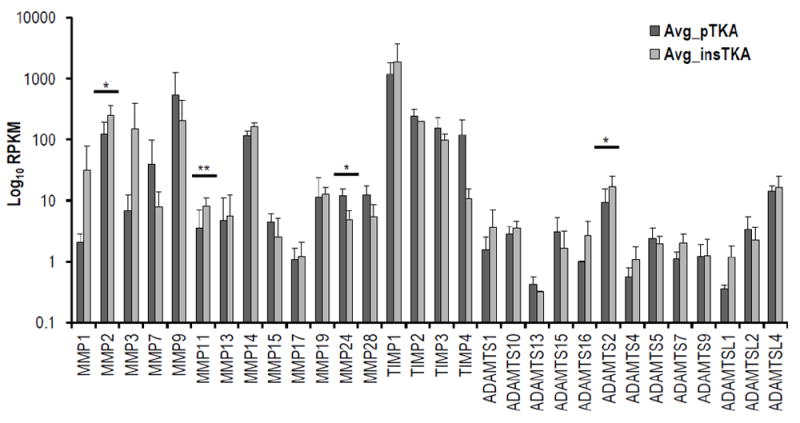

Focused RNA-seq analysis – ECM remodeling

Focused hierarchical clustering analyses among sample groups (pTKA and insTKA) for genes related to ECM-remodeling, resulted in poorly defined sample groups. For example, sample 16B grouped with pTKA samples (Figure 4a, 4b) in both the GeneMania and Pvclust analyses, despite strong statistical support for this relationship based on the ECM remodeling partition of the RNA-seq data (Figure 4b, 4c). When analyzed independently, all collagen-related genes were elevated in tissues with flexion instability after TKA. Specifically, mRNA expression values for genes related to collagen production were consistently elevated in samples taken from instability TKA patients, and five were statistically significant (p-value<0.05; COL1A1, COL3A1, COL5A1, COL8A1, and COL8A2) while three others were trending toward significance below a p-value of 0.1 (COL1A2, COL5A2, and COL27A1) (Figure 4d). This striking pattern applied to all significantly expressed collagen genes detected in the RNA-seq analyses described above. Similarly, ECM degradation-related genes revealed patterns of increased RPKM values in samples from instability TKA patients (18 out of 30 highly expressed genes), and of these MMP2, MMP11, ADAMTS2 were statistically significantly elevated in instability TKA samples (Figure 4e).

Figure 4.

Hierarchical clustering analyses on ECM remodeling genes only by (a) GeneMania, (b) Pvclust, (c) standard error versus p-value plot. (d) Focused RNA-seq analysis of ECM-formation related genes (e.g., Collagens), (e) focused RNA-seq analysis of ECM degradation-related genes (e.g., MMPs, TIMPs, ADAMTSs). (*=<0.1; **<0.05)

Focused RNA-seq analysis – chemokine signaling

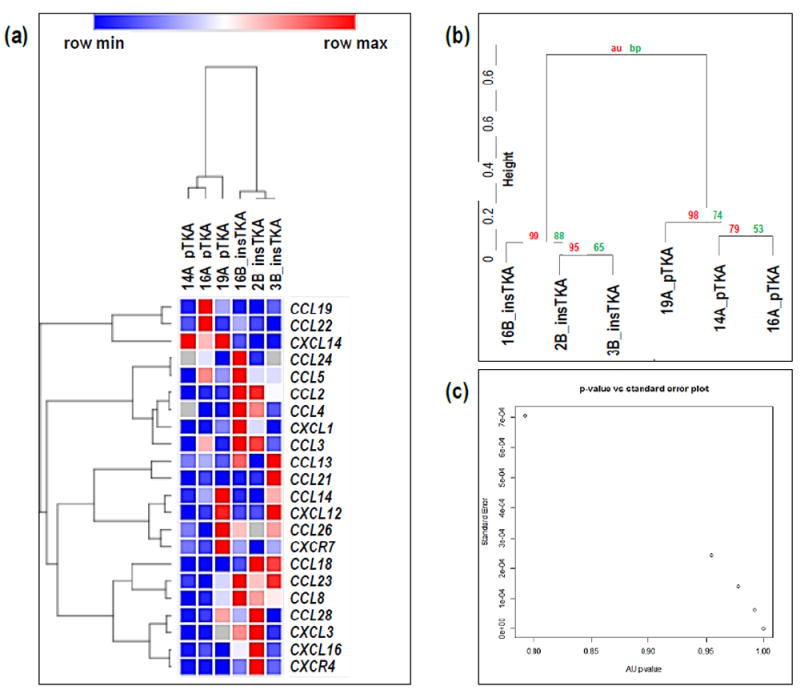

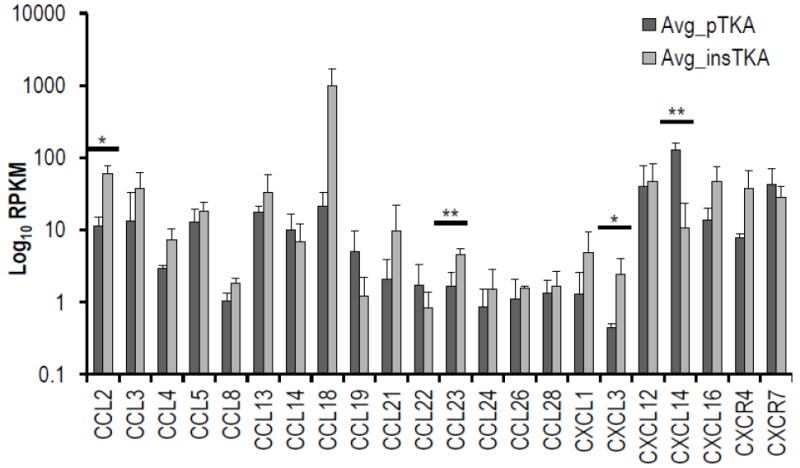

Hierarchical clustering of chemokine signaling genes partitioned from RNA-seq data revealed well-supported groupings of samples by tissue type (au-vales>98) (Figure 5a, b, c). Seventeen of twenty-two expressed chemokine ligands (CCLs and CXCLs) were upregulated in instability TKA samples, and four were significantly higher than pTKA samples (p<0.1) (Figure 5d). Genes involved in the inflammatory response were specifically investigated for differences between each sample group, and a lack of clustering by sample type (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Hierarchical clustering analyses on cytokine genes only by (a) GeneMania, (b) Pvclust, (c) standard error versus p-value plot. (d) Focused RNA-seq analysis of cytokines (e.g., CCL, CXC). (*=<0.1; **<0.05)

qPCR validation

Despite low variation detected among RNA-seq samples for the expression of genes commonly used to normalize gene expression data (Supplementary Figure 1), we proceeded to analyze additional samples by RT-qPCR. A panel of sixteen human primers were used to determine expression patterns among 16 samples within each sample group (n=32 total). Any patient samples with low RNA extraction yields were omitted from the study. For all remaining samples included in the analysis, average values and t-test statistics were used to calculate differential gene expression patterns among groups. For all sixteen human genes analyzed by qPCR, normalized expression values were elevated in insTKA patient samples (except CD248, and ID3 and cFOS). Below the p<0.05 threshold of statistical significance were the following genes that were upregulated in instability TKA samples: COL3A1, TNC, ACAN, HIST2H4, ACTA2, and COL1A1 (p<0.1) (Supplementary Figure 2 and data not shown). ID3 was significantly lower in instability TKA samples based on qPCR analysis.

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSIONS

Flexion instability after TKA unfortunately occurs after the procedure, and is currently defined by clinical history, physical examination, and radiograph [17, 34, 35]. While investigating the clinical and biomechanical etiologies of failure in this condition, exploring the biomolecular differences between patients with and without flexion instability after TKA may yield insights into the subject of host tissue response [36, 37]. Studies investigating the genetic profile of biologic mediators involved in the acute post-surgical healing process reveal this critical period is responsible for the inflammatory cascade, tissue remodeling, and scar tissue formation initiated in the microenvironment surrounding implanted prostheses [38]. While the continued success of total joint arthroplasty has been reported for decades [39, 40], limited molecular data describing many common and devastating orthopedic complications have yet to be analyzed [15, 35]. RNA-Seq is a useful tool for identifying significant gene expression differences between experimental and control tissue samples, and may allow for more directed studies to target ECM remodeling genes implicated in the process of post-surgical joint instability. Targeted analysis of these markers in the post-surgical setting may also allow identification of high-risk patients receptive to TKA instability mitigation.

Matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs), are pivotal biological proteases responsible for the degradation of ECM in normal physiological processes such as tissue repair, remodeling, morphogenesis, and development [25, 41]. MMP functional gene polymorphisms contribute to patient-specific differences in susceptibility and outcomes for cardiovascular diseases (e.g., coronary artery disease, stenosis, myocardial infarction, coronary aneurysm, stroke, and large artery stiffness) [42]. In principle, MMP genotyping could be used to identify patients most likely to develop unfavorable prognoses in response to invasive medical treatments including TKA.

In orthopedics, limited data exist on the possible role of MMPs in the pathogenesis of bone turnover and soft tissue necrosis following total joint arthroplasty. Some studies have demonstrated the dysregulation of MMPs in degenerative, inflammatory diseases like osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibrotic conditions [27, 43], while others have noted a correlation between elevated MMPs and periprosthetic loosening / osteolysis [24, 25, 44]. For example, Yan et al. [24] demonstrated elevated expression of MMP1 and MMP2 in cases of prosthetic loosening following THA. Ishiguro et al. [45] also documented higher mRNA gene expression levels of MMPs and TIMPs in the cemented periacetabular tissue of THA failures that resulted from aseptic loosening. While THA aseptic loosening is a pathophysiologically distinct process from TKA instability, they likely share common processes and relevant markers that should be monitored after surgery [37]. Other studies have characterized Heme Oxygenase-1 (HMOX-1, or HO-1), an essential enzyme for heme catabolism which utilizes heme as its main catalytic substrate. However, evidence supports the activation of this enzyme by other non-heme substrates, such as exposure to heavy metals, inflammatory cytokines, and prostaglandin synthesis to induce HMOX-1 to mediate cellular stress-response reactions in the tissue [46].

Our study has shown elevated gene expression of ECM remodeling genes suggesting a potential relationship between extracellular matrix degradation and oxidative stress exposure during tissue remodeling. As Choi et al [46] demonstrated in various pulmonary pathologies, tissue exposure to oxidative insults can stimulate an upregulation of HMOX-1. Similarly, Jais et al. [47] showed cytoprotective properties of HMOX-1 as anti-inflammatory mediators in patients with chronic metabolic inflammation or “metaflammation”. Our results support the suggestion that oxidative-response events may be correlated to chronic local inflammation typical of TKA instability, and potentially exacerbate uncontrolled movement along the bone-soft-tissue interface [3, 14]. Notably, recurrent effusions after bleeding [3, 13], or synovial entrapment [48, 49], would also be expected to correlate with elevations in HMOX-1 expression as a biological damage control mechanism. Alternatively, studies on osteoarthritis progression have shown HMOX-1 regulates MMP1 secretion via an oxidative stress mediator, Nox4 [50] suggesting that indirect consequences of TKA instability to alter cell responses should not be ignored. In summary, efforts to further isolate the effects of physical and biological processes (e.g., ECM remodeling, oxidative stress response) that contribute to flexion instability after TKA will likely yield exciting results that guide clinicians toward advanced prevention, detection and treatment strategies to reduce overall rates of TKA instability.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Focused RNA-seq analysis: normalizers

Supplementary Figure 2. qPCR validation of key results from RNA-seq analysis. Primers used for qPCR are listed as follows: AKT1 (forward- ATGGCGCTGAGATTGTGTCA; reverse-CCCGGTACACCACGTTCTTC), GAPDH (forward- ATGTTCGTCATGGGTGTGAA; reverse- TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA), COL1A1 (forward- GTAACAGCGGTGAACCTGG; reverse- CCTCGCTTTCCTTCCTCTCC), COL3A1 (forward- TTGAAGGAGGATGTTCCCATCT; reverse- ACAGACACATATTTGGCATGGTT).

Highlights.

Flexion instability after total knee arthroplasty is examined using primary clinical tissues

Gene expression levels are collected by RNA-seq and RT-qPCR

High-throughput data and bioinformatics techniques are used to compare differentially expressed genes

Genes related to extracellular matrix remodeling and oxidative stress are highlighted

Possible future strategies to mitigate flexion instability after total knee arthroplasty are discussed

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Abdel and van Wijnen laboratories, and in particular Scott M. Riester, M.D., for stimulating discussions and/or assistance with reagents and procedures. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01 AR049069 (to AJVW) and F32 AR068154 (to EAL). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We also appreciate the generous philanthropic support of William H. and Karen J. Eby, as well as the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation, and the charitable foundations in their names. Matthew P. Abdel, Arlen D. Hanssen, and Daniel J. Berry receive royalties for hip and knee related implants.

Footnotes

No other authors have conflicts of interest to disclosure.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cottino U, et al. Instability After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(2):311–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrie JR, Haidukewych GJ. Instability in total knee arthroplasty : assessment and solutions. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-b(1 Suppl A):116–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B1.36371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parratte S, Pagnano MW. Instability after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):184–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel MP, et al. Contemporary failure aetiologies of the primary, posterior-stabilised total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-b(5):647–652. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B5.BJJ-2016-0617.R3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh CK, et al. Periprosthetic Joint Infection Is the Main Cause of Failure for Modern Knee Arthroplasty: An Analysis of 11,134 Knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemes S, et al. Historical view and future demand for knee arthroplasty in Sweden. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(4):426–31. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2015.1034608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurtz S, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibanda N, et al. Revision rates after primary hip and knee replacement in England between 2003 and 2006. PLoS Med. 2008;5(9):e179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurtz SM, et al. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdel MP, et al. Stepwise surgical correction of instability in flexion after total knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(12):1644–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B12.34821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel MP, Haas SB. The unstable knee: wobble and buckle. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(11 Supple A):112–4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.34325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Gaizo DJ, Della Valle CJ. Instability in primary total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e519–21. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20110714-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwab JH, et al. Flexion instability without dislocation after posterior stabilized total knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;440:96–100. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200511000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pagnano MW, et al. Flexion instability after primary posterior cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998(356):39–46. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seil R, Pape D. Causes of failure and etiology of painful primary total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1418–32. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1631-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehring TK, et al. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392):315–8. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suarez J, et al. Why do revision knee arthroplasties fail? J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6 Suppl 1):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker PN, et al. Patient satisfaction with total knee replacement cannot be predicted from pre-operative variables alone: A cohort study from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-b(10):1359–65. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B10.32281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn SL, et al. Gene expression changes in damaged osteoarthritic cartilage identify a signature of non-chondrogenic and mechanical responses. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(8):1431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang K, et al. RNA sequencing from human neutrophils reveals distinct transcriptional differences associated with chronic inflammatory states. BMC Med Genomics. 2015;8:55. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0128-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewallen EA, et al. The synovial microenvironment of osteoarthritic joints alters RNA-seq expression profiles of human primary articular chondrocytes. Gene. 2016;591(2):456–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verhoekx JS, et al. The mechanical environment in Dupuytren’s contracture determines cell contractility and associated MMP-mediated matrix remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(2):328–34. doi: 10.1002/jor.22220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araki Y, Mimura T. Matrix Metalloproteinase Gene Activation Resulting from Disordred Epigenetic Mechanisms in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(5) doi: 10.3390/ijms18050905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Y, et al. Genetic susceptibility to total hip arthroplasty failure: a case-control study on the influence of MMP 1 gene polymorphism. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:177. doi: 10.1186/s13000-014-0177-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syggelos SA, et al. Extracellular Matrix Degradation and Tissue Remodeling in Periprosthetic Loosening and Osteolysis: Focus on Matrix Metalloproteinases, Their Endogenous Tissue Inhibitors, and the Proteasome. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/230805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JJ, et al. Expression and significance of MMP3 in synovium of knee joint at different stage in osteoarthritis patients. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7(4):297–300. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tchetverikov I, et al. MMP protein and activity levels in synovial fluid from patients with joint injury, inflammatory arthritis, and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(5):694–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.022434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coen N, et al. Particulate debris from a titanium metal prosthesis induces genomic instability in primary human fibroblast cells. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(4):548–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dudakovic A, et al. High-resolution molecular validation of self-renewal and spontaneous differentiation in clinical-grade adipose-tissue derived human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115(10):1816–28. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warde-Farley D, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W214–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki R, Shimodaira H. Pvclust: an R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(12):1540–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang MJ, et al. Diagnosis, causes and treatments of instability following total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(2):61–7. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2014.26.2.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreland JR. Mechanisms of failure in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988(226):49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuan RS, et al. What are the local and systemic biologic reactions and mediators to wear debris, and what host factors determine or modulate the biologic response to wear particles? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(Suppl 1):S42–8. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200800001-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallo J, et al. Osteolysis around total knee arthroplasty: a review of pathogenetic mechanisms. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(9):8046–58. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abu-Amer Y, Darwech I, Clohisy JC. Aseptic loosening of total joint replacements: mechanisms underlying osteolysis and potential therapies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/ar2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Memtsoudis SG, et al. Trends in demographics, comorbidity profiles, in-hospital complications and mortality associated with primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(4):518–27. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.01.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirksey M, et al. Trends in in-hospital major morbidity and mortality after total joint arthroplasty: United States 1998-2008. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(2):321–7. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825b6824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagase H, Visse R, Murphy G. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(3):562–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye S. Influence of matrix metalloproteinase genotype on cardiovascular disease susceptibility and outcome. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(3):636–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burrage PS, Mix KS, Brinckerhoff CE. Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Front Biosci. 2006;11:529–43. doi: 10.2741/1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta SK, et al. Osteolysis after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6):787–99. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishiguro N, et al. mRNA expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase in interface tissue around implants in loosening total hip arthroplasty. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;32(4):611–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199612)32:4<611::AID-JBM14>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi AM, Alam J. Heme oxygenase-1: function, regulation, and implication of a novel stress-inducible protein in oxidant-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15(1):9–19. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jais A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 drives metaflammation and insulin resistance in mouse and man. Cell. 2014;158(1):25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kindsfater K, Scott R. Recurrent hemarthrosis after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(Suppl):S52–5. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Worland RL, Jessup DE. Recurrent hemarthrosis after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(8):977–8. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rousset F, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates matrix metalloproteinase MMP-1 secretion and chondrocyte cell death via Nox4 NADPH oxidase activity in chondrocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Focused RNA-seq analysis: normalizers

Supplementary Figure 2. qPCR validation of key results from RNA-seq analysis. Primers used for qPCR are listed as follows: AKT1 (forward- ATGGCGCTGAGATTGTGTCA; reverse-CCCGGTACACCACGTTCTTC), GAPDH (forward- ATGTTCGTCATGGGTGTGAA; reverse- TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA), COL1A1 (forward- GTAACAGCGGTGAACCTGG; reverse- CCTCGCTTTCCTTCCTCTCC), COL3A1 (forward- TTGAAGGAGGATGTTCCCATCT; reverse- ACAGACACATATTTGGCATGGTT).