SUMMARY

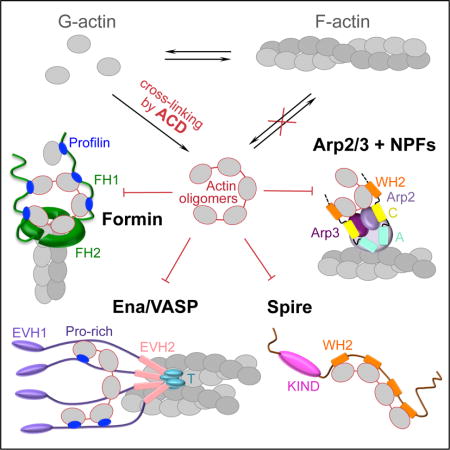

Delivery of bacterial toxins to host cells is hindered by host protective barriers. This obstruction dictates a remarkable efficiency of toxins, a single copy of which may kill a host cell. Efficiency of actin-targeting toxins is further hampered by an overwhelming abundance of their target. The actin cross-linking domain (ACD) toxins of Vibrio species and related bacterial genera catalyze the formation of covalently cross-linked actin oligomers. Recently, we reported that the ACD toxicity can be amplified via a multivalent inhibitory association of actin oligomers with actin assembly factors formins, suggesting that the oligomers may act as secondary toxins. Importantly, many proteins involved in nucleation, elongation, severing, branching, and bundling of actin filaments contain G-actin-binding WASP homology motifs 2 (WH2) organized in tandems and, therefore, may act as a multivalent platform for high-affinity interaction with the ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers. Using live-cell single-molecule speckle (SiMS) microscopy, TIRF microscopy, and actin polymerization assays, we show that, in addition to formins, the oligomers bind with high affinity and potently inhibit several families of actin assembly factors: Ena/VASP, Spire, and the Arp2/3 complex, both in vitro and in live cells. As a result, ACD blocks the actin retrograde flow and membrane dynamics, and disrupts association of Ena/VASP with adhesion complexes. This study defines ACD as a universal inhibitor of tandem-organized G-actin binding proteins that overcomes the abundance of actin by redirecting the toxicity cascade towards less abundant targets and thus leading to profound disorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and disruption of actin-dependent cellular functions.

eTOC Blurb

The shared ability of actin assembly factors to bind several actin molecules aids actin filament nucleation and growth. Kudryashova, Heisler, et al. show that bacterial toxin ACD targets this common property by producing covalent actin oligomers, which potently inhibit many actin assembly factors leading to disruption of cellular actin dynamics.

INTRODUCTION

The actin cytoskeleton plays numerous vital roles in innate and adaptive immune responses, and as such, represents a common and attractive target for microbial toxins. Despite the numerous toxins that target the actin cytoskeleton, few of them modify actin molecules directly [1]. Due to the efficiency of immune barriers [2], delivery of protein toxins to host cells is heavily suppressed, which applies a strong evolutionary pressure on toxin efficiency. Toxicity amplification is often achieved by targeting essential, low abundant host proteins in signaling or neurotransmission cascades [3-6]; whereas actin, a highly abundant structural protein, is a rare exception to this rule. The actin cross-linking domain (ACD), produced by gram-negative Vibrio, Aeromonas, and other species, is one of the toxins that utilize actin monomers as a substrate [7]. ACD is delivered to the host cytoplasm as one of several effectors of the multifunctional auto-processing repeats-in-toxin (MARTX) toxins [8] or as a single effector domain fused to valine–glycine repeat protein G1 (VgrG1) toxin of the type VI secretion system [9]. Once inside a host cell, ACD catalyzes the covalent cross-linking of actin monomers into various-length oligomers through a formation of amide bonds between the side chains of lysine-50 and glutamate-270 [10, 11].

The oligomers fail to polymerize, and their bulk accumulation eventually leads to cell rounding [12]. However, to be effective, this toxicity mechanism would require high doses of the toxin, reducing its value for the microorganisms. Instead, an unusual “gain–of–function” mechanism of toxicity amplification was recently proposed whereby the actin oligomers, while showing negligible effects on spontaneous actin dynamics, act as potent secondary toxins that bind to and directly inhibit formins [13]. Formins function as homodimers that nucleate actin filaments and accelerate elongation of filament barbed ends, while also protecting them from the inhibitory activity of capping proteins [14]. Formins contain conserved formin-homology domains 1 and 2 (FH1, FH2) capable of simultaneously interacting with actin filament ends and several actin-profilin complexes. Recently we demonstrated that by providing a multivalent platform for high-affinity interaction with FH1 and FH2 domains, the ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers potently block nucleation and elongation activities of formins in vitro, which correlated with a distortion of the host cytoskeleton in living cells [13].

Notably, a diverse pool of actin-organizing proteins involved in nucleation, elongation, severing, branching, and bundling of actin filaments contain G-actin binding Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome homology 2 (WH2) motifs [15] that are arranged in tandem or closely positioned upon functional oligomerization, i.e., they share the property targeted by the ACD-cross-linked oligomers in case of formins. We employed single-molecule speckle (SiMS) live-cell microscopy to demonstrate that low doses of the oligomers effectively shut down the dynamics of formins and several families of WH2-containing proteins. Specifically, the oligomers strongly inhibit the dynamics of mDia1, Ena/VASP, Spire, and the Arp2/3 complex nucleation-promoting factors (NPF) in lamellipodia and filopodia, leading to disorganization of adhesion contacts and arrest of actin dynamics at the leading edge of affected cells. Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM), bulk actin polymerization assays, and modeling of actin polymerization with sets of ordinary differential equations supported the experimental data and revealed additional details on the proposed mechanisms of oligomer-induced inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex, Ena/VASP, and Spire. Therefore, we report that ACD converts actin into toxic covalent oligomers that are universally poisonous towards numerous tandem and oligomeric actin organizers.

RESULTS

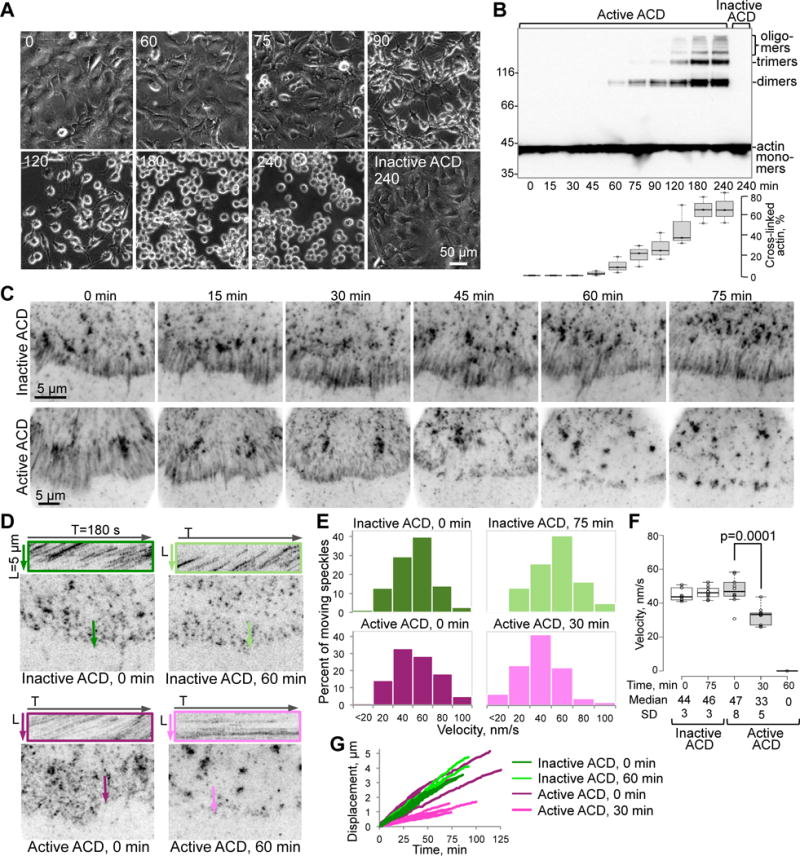

Actin retrograde flow is arrested by low doses of the oligomers

In intestinal epithelial monolayers, ACD toxicity leads to a prominent loss of epithelial integrity due to cytoskeleton distortions when only 2–6% of actin is cross-linked into oligomers [13]. We employed single molecule speckle microscopy (SiMS) to reveal the nature of these distortions by monitoring dynamics of actin and actin-binding proteins in living cells. To this end, ACD was transported to the cytoplasm of Xenopus laevis XTC fibroblasts via the Anthrax toxin-based delivery pathway [12]. Within 30 min of toxin addition, when <1% of actin was cross-linked to the oligomers (Figures 1A,B), the actin retrograde flow rate was inhibited from 47 to 33 nm/s (Figure 1F). The flow was completely halted by 45 min (Figures 1C–G; Movie S1), when only ~2% of actin was cross-linked. This was in striking contrast with unperturbed actin dynamics in cells treated with a catalytically inactive mutant of ACD (Figures 1C–G; Movie S1). Of note, the cell edge was not retracted at these early stages and the characteristic cell rounding [12, 16] occurred at later stages of ACD toxicity (Figures 1A and B). Although originally the potent disruption of actin functions by the ACD cross-linked actin oligomers was attributed to their high affinity multivalent interactions with formins (Heisler et al., 2015), actin retrograde flow is largely controlled by NPFs and the Arp2/3 complex, suggesting that these factors may also be affected by ACD.

Figure 1. ACD toxicity disorganizes retrograde flow of EGFP-actin in living cells.

(A,B) Changes in cell morphology (A) and accumulation of ACD-cross-linked actin species (B) were monitored upon treating XTC fibroblasts with the LFNACD/PA mixture for the indicated periods of time (min) with a catalytically inactive LFNACD mutant as a control (see STAR Methods). Cross-linked actin was quantified and expressed as mean values ± SE from three independent replicates of the cell lysate immunoblots stained for actin (B).

(C) Average intensity projections from time-lapse images of peripheral regions of XTC cells expressing low levels of EGFP-actin. Projections of EGFP-actin speckles moving by retrograde flow appear as smeared traces perpendicular to the cell edge in the lamellipodia area (5–10 μm from the cell edge). This flow was hindered at 30 min of active ACD treatment (notably shorter traces) and ceased after 60 min (no smeared traces).

(D) Kymographs (in colored boxes) of areas shown on the corresponding images as colored lines were obtained from the same time-lapse images as in (C). After cell treatment with inactive ACD (0 and 60 min) or active ACD at 0 min, moving EGFP-actin speckle trajectories appear as diagonal strikes on the kymographs. Horizontal straight trajectories upon 60-min treatment with active ACD indicate stalled actin dynamics.

(E–G) Movement of individual EGFP-actin speckles from the time-lapse images represented as histogram distributions of the velocities of moving speckles’ (E) calculated based on 100–300 displacement events, a box plot of velocities (F) calculated from individual speckle tracks (n=10; median velocities of actin speckles with standard deviations (SD) are indicated), and representative individual speckle tracks (displacement versus time) plotted for the indicated ACD-treatment periods (G). Stationary speckles were not analyzed in (E) and (G).

See also Movie S1.

Retrograde flow of the Arp2/3 complex is inhibited by ACD in live cells

Similar to the retrograde flow of EGFP-actin (Figure 1; Movie S1), the retrograde flow of the Arp2/3 complex was notably hindered at 45 min and ceased after 60 min of treatment with ACD, as monitored by fluorescence of the EGFP-p40 subunit of the complex (Figures 2A–C; Movie S2). In accordance with previous observations [17], EGFP-WAVE, a representative type I NPF (Figure 2D), was localized to filopodia tips and moved along the lamellipodia edge (Movie S3). Upon ACD treatment, its dynamics at the membrane, as well as the overall dynamics of the leading edge were completely suppressed within 60 min, as judged by a lack of membrane deformations (Figures 2E and F; Movie S3).

Figure 2. Inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex and its activators WAVE and N-WASP-VCA by the ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers.

(A–C) Movement of individual speckles of EGFP-p40 subunit of the Arp2/3 complex in XTC cells represented as (A) kymographs (colored boxes), (B) distributions of moving p40 speckles’ velocities (100–300 displacement events), and (C) a box plot of velocities calculated from individual speckle tracks (n=8; median velocities and SD are indicated). See also Movie S2.

(D) Domain structure of X. laevis WAVE: SHD, SCAR-homology domain; B, basic region; Pro-rich, proline-rich region; W, WH2-domain; C, central domain; A, acidic motif. Residue numbers delineating domain borders are indicated.

(E,F) The cell edge dynamics of EGFP-WAVE-transfected XTC cells is illustrated by changes of the cell contour (E) in two images taken within 60 seconds from each other (red line – at 0 s, blue – at 60 s). (F) Quantitation of the cell edge dynamics represented as an area change per micrometer of the cell edge length (data is mean ± SE; n=4). See also Movie S3.

(G) Domain organization of GST-N-WASP-VCA used in native PAGE (H), TIRFM (J–L), and pyrene assays (M–O) – the C-terminal part (a.a. 422–505) of bovine N-WASP: W, WH2-domain; C and A, central and acidic domains, respectively.

(H) A representative native PAGE (n=3) of the oligomers titrated by the Arp2/3 complex, GST-N-WASP-VCA, and their combination.

(I) Fluorescein-labeled (green asterisk) murine N-WASP-VCA (a.a. 399-501) with two WH2-domains and without GST-tag (50 nM) was used in fluorescence polarization assays to calculate the Kds of N-WASP-VCA to actin monomers and actin oligomers (data is mean ± SD; n=3). Insert is a blow-up view of 0 to 1 μM [Actin] range.

(J,K) Branching events formed upon mixing of Alexa 488-actin with the Arp2/3 complex (20 nM) and GST-N-WASP-VCA (40 nM) in the presence or absence of oligomers in TIRFM (J), were quantified and normalized to the total filament lengths (K); mean ± SD; n=3. See also Movie S4.

(L) Two-color TIRFM (left and middle panels) demonstrates that existing branches formed in the presence of Arp2/3-N-WASP-VCA (green filaments) do not dissociate and continue to elongate after the addition of oligomers and a concomitant removal of Arp2/3-N-WASP complexes (magenta filaments). Oligomers block branch formation (right panel; green filaments), which is restored upon removal of the oligomers (magenta filaments).

(M–O) Effects of the oligomers on the GST-N-WASP-VCA-activated Arp2/3-mediated actin nucleation in bulk pyrenyl-actin assays in the absence (M; see also Figure S1A) and presence (N) of PFN1; relative inhibition data in (O; see STAR Methods) presented as mean ± SD, n=3.

Actin oligomers bind to N-WASP-VCA with high affinity and inhibit nucleation by the N-WASP-VCA-activated Arp2/3 complex in vitro

To test whether oligomers can bind to the Arp2/3 complex or its activators, we focused on the VCA region of N-WASP, another type I NPF. Since the active form of N-WASP is a dimer [18], an artificially dimerized GST-VCA construct was used (Figure 2G). Electrophoretic mobility shifts on native polyacrylamide gel revealed interaction of the oligomers with GST-N-WASP-VCA in the presence and absence of the Arp2/3 complex, but not with the Arp2/3 complex alone (Figure 2H). Furthermore, the affinity of fluorescein-labeled N-WASP-VCA (Figure 2I) to the oligomers was found to be more than 200 times higher than to G-actin (Kd = 8 nM and 1.8 μM, respectively; Figure 2I), in agreement with the proposed role of multivalent interactions in the oligomers’ toxicity.

Accordingly, the oligomers strongly inhibited branching of actin filaments in the presence of GST-N-WASP-VCA-activated Arp2/3 complex (Figures 2J and K; Movie S4), but neither affected elongation of the existing barbed ends, nor caused dissociation of the existing branches (Figure 2L) in TIRFM experiments. Although actin oligomers have negligible effect on spontaneous actin polymerization [13], they potently inhibited the nucleation by the GST-N-WASP-VCA-activated Arp2/3 complex in bulk pyrene-actin polymerization assays (Figures 2M–O). Notably, the observed inhibition was over two-fold more potent in the absence of profilin than in its presence (appKd = 9.8 nM and 23 nM, respectively), likely reflecting a preferable interaction of N-WASP with free actin leading to channeling of actin-profilin complexes towards formins [19]. Mathematical modeling (see STAR Methods) of Arp2/3-mediated polymerization in the presence of the oligomers (Figure S1A) demonstrated good fits to the experimental data (Figure 2M) with an affinity of the oligomers for the Arp2/3-VCA complex slightly higher than the apparent Kd (compare measured appKd = 9.8 nM in the absence of profilin with the model’s Kd = 2 nM).

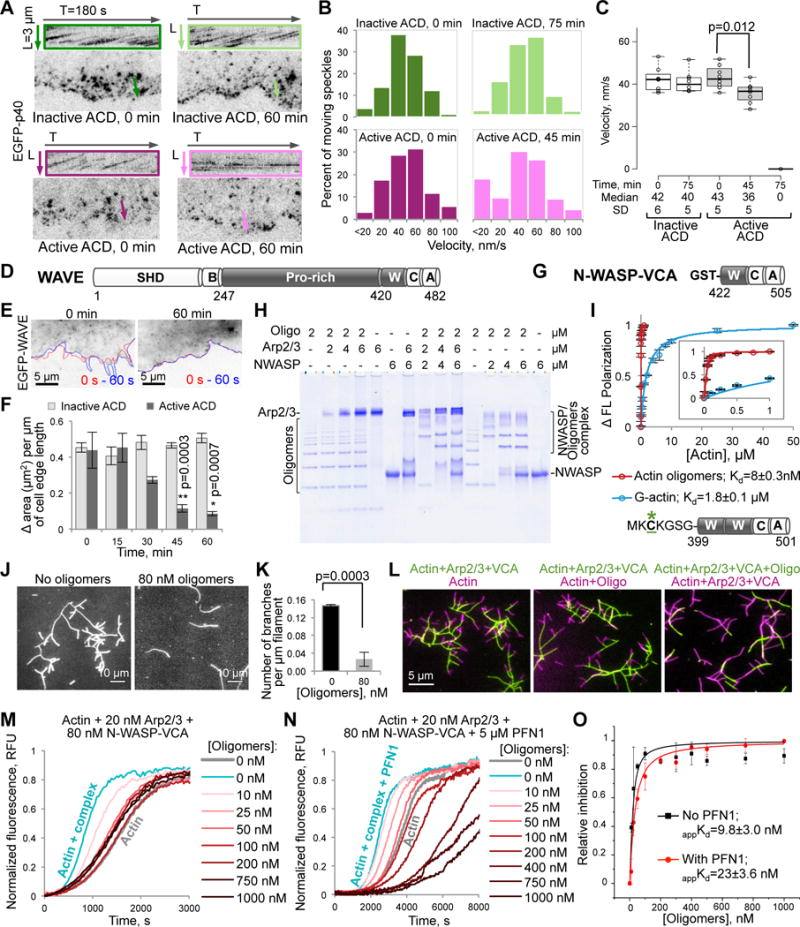

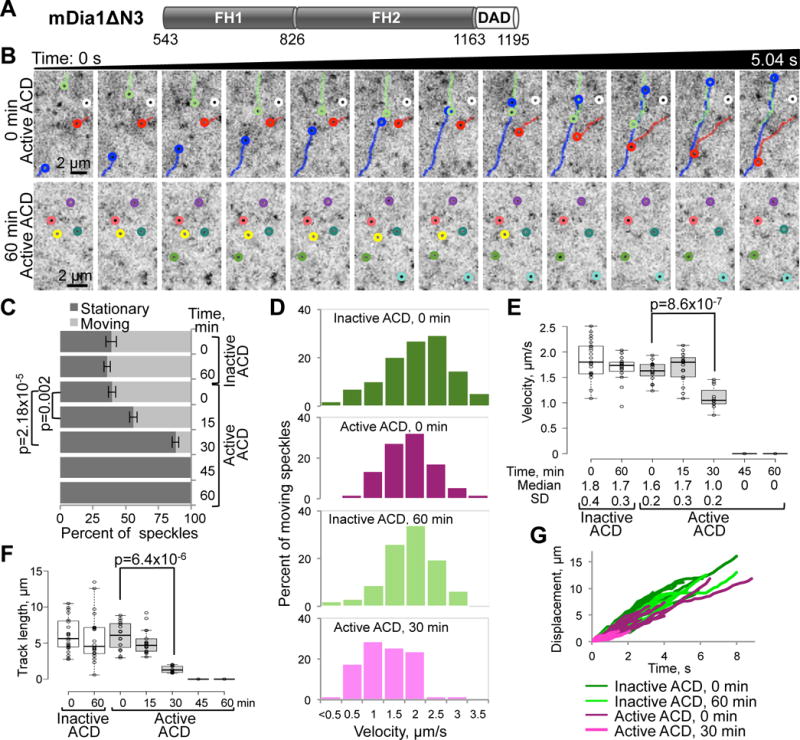

Directional movement of mDia1 formin in live cells is stalled at early points of ACD treatment

Unlike that of the Arp2/3 complex, formins’ dynamics is not directly associated with the retrograde flow. The unique role of formins in cell membrane dynamics and cell junction maintenance was reflected in the epithelial barrier leakage observed upon cytoplasmic delivery of ACD, which was similar to that caused by a small-molecule inhibitor of formins (SMIFH2) and correlated with potent inhibition by the oligomers of several human formins in vitro [13]. Yet, the effects of ACD on formin dynamics in live cells were not investigated. We explored formin dynamics in XTC cells by following the fluorescence of a fusion construct of EGFP with a constitutively active mutant of mouse formin mDia1, EGFP-mDia1ΔN3 (Figure 3; Movie S5). In the control experiments (and at early time points of 0–15 min of active ACD treatment), formins moved with a median velocity of ~1.7 μm/s (Figures 3D and E), characteristic for formin-accelerated barbed end elongation and similar to the previously reported value of 2 m/s for this construct in XTC cells [20]. A statistically significant reduction in the fraction of moving EGFP-mDia1ΔN3 molecules was observed as early as 15 min after the addition of ACD (Figure 3C). At the 30 min time point, the fraction of moving speckles was further reduced along with the lengths of individual tracks and the velocities of moving speckles (Figures 3C–G; Movie S5), while the complete halt of all speckles was observed at 45 min, when cross-linked actin dimers constituted <2% of total actin (Figure 1B).

Figure 3. Inhibition of the directional movement of mDia1 by ACD in living cells.

(A) Domain organization of mDia1ΔN3 (a.a. 543-1192 of murine mDia1): FH1 and FH2, formin-homology domains 1 and 2; DAD, diaphanous autoregulatory domain.

(B) Representative tracks of EGFP-mDia1ΔN3 speckles in XTC cells treated with active ACD are shown on series of 12 consecutive images taken with 0.42s intervals at the beginning of the experiment (0 min time point; upper panels) and after 1 h of active ACD treatment (lower panels), where virtually all speckles have stopped.

(C–G) Individual EGFP-mDia1ΔN3 speckles from the time-lapse images were analyzed for indicated ACD-treatment periods. (C) Fractions of stationary and moving EGFP-mDia1ΔN3 speckles for each indicated ACD-treatment condition were calculated from three sets of 10–15 consecutive images (~2-s duration each) taken at the beginning, middle, and end of each 45-s movie (Movie S5) and presented as mean values ± SD. (D) Velocity distributions of moving speckles calculated based on 100–300 displacement events. (E) A box plot of velocities calculated from 10–20 individual speckle tracks; median velocities and SD are indicated. (F) A box plot of distances traveled by each speckle in a track. (G) Individual tracks (displacement versus time) of moving speckles; note significantly shorter tracks for EGFP-mDia1ΔN3 speckles after 30-min ACD treatment. Stationary speckles are not presented in (D) and (G). See also Movie S5.

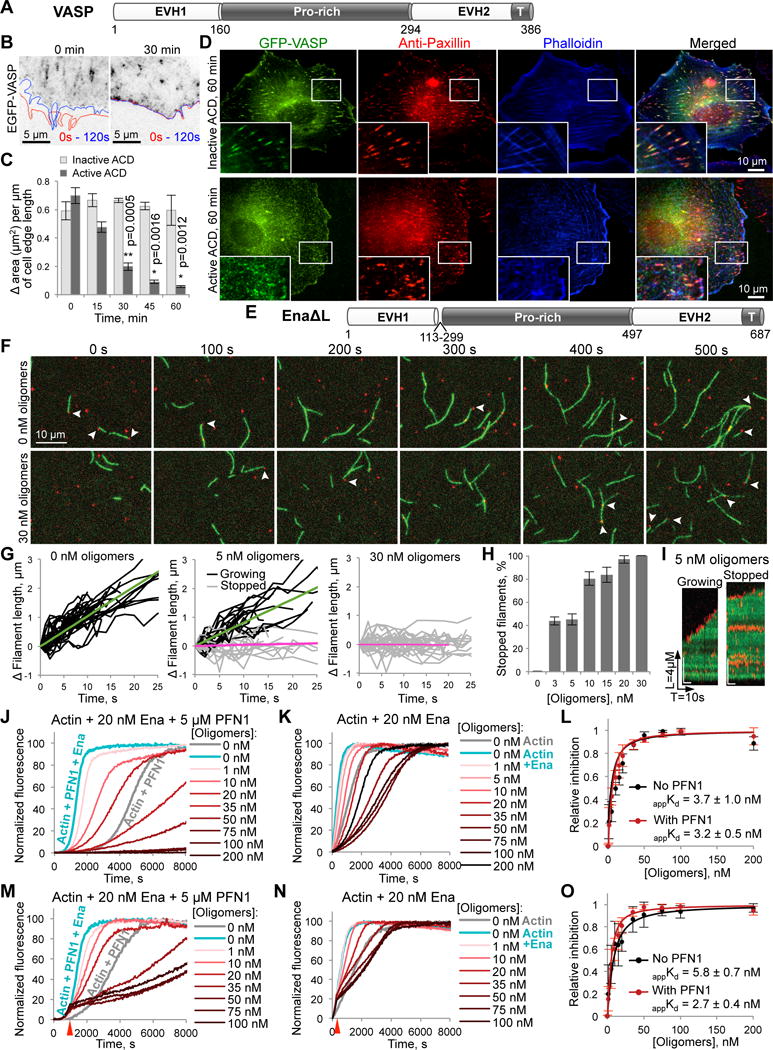

Ena/VASP dynamics and its association with focal adhesions are disrupted by ACD

The proteins of Ena/VASP family are major contributors to the actin dynamics driving membrane protrusions and maintaining focal adhesion sites [21]. Similar to formins and NPFs, Ena/VASP can interact with several G-actins via their WH2-domains and poly-proline stretches (Figure 4A), an ability that is further enhanced by their tetrameric organization. In XTC cells, EGFP-VASP is highly enriched at the cell membrane, at the tips and body of filopodia, and in adhesion contacts (Figure 4B; Movie S6). However, its association with the filaments is either too abundant (as in adhesion contacts) or very transient (as in lamellipodia) for recording velocities of individual speckles, in agreement with a previous report [22]. Addition of active ACD strongly inhibited overall dynamics of lamellipodia and abolished the formation of filopodia in as early as 30 min (Figures 4B and C). VASP association with the membrane appeared to be strengthened by the toxin, possibly reflecting its tightened association with filament ends (Movie S6). Simultaneously, co-localization of VASP clusters with the focal adhesions (revealed by anti-paxillin staining) and the ends of stress fibers was disrupted: both VASP and paxillin were dispersed into smaller foci, only poorly overlapping with the stress fibers (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Inhibitory effects of actin oligomers on Ena/VASP-mediated processive filament elongation.

(A) Domain structure of X. laevis VASP protein: EVH1 and EVH2, Ena/VASP-homology domains 1 and 2; Pro-rich, (poly)proline-rich domain. EVH2 contains a putative WH2-domain and a tetramerization domain (T).

(B,C) The leading edge dynamics in EGFP-VASP-transfected XTC cells is illustrated by changes of the cell contour (B) in two images taken within 2 min from each other (red line – at 0 s, blue – at 120 s). The dynamics was stalled within 30 min upon delivery of active ACD as demonstrated by virtually overlapping cell contours. (C) Quantitation of the cell edge dynamics represented as an area change per micrometer of the cell edge length (data is mean ± SE; n=4). See also Movie S6.

(D) XTC cells expressing high levels of EGFP-VASP were treated for 60 min with either active or inactive ACD, stained for paxillin (red), and counterstained with phalloidin (blue). “Blow-up” images of boxed areas are shown in the lower left corners.

(E) Domain organization of EnaΔL construct corresponding to fly Ena lacking a linker region (a.a. 113-299); domain designation as in (A).

(F–I) Single-molecule TIRFM time-lapse images (F) of Alexa 488-actin (green) polymerization in the presence of 0.5 nM SNAP-EnaΔL (red), 3 µM chickadee, and either no oligomers or 30 nM oligomers. Arrows indicate SNAP-EnaΔL-bound barbed ends. (G) Filament elongation traces of SNAP-EnaΔL-bound filaments with 0, 5, and 30 nM oligomers. Fit lines show average growth rates of SNAP-EnaΔL-bound growing filaments (green fits) and SNAP-EnaΔL-bound stopped filaments (magenta fits). (H) The percent of SNAP-EnaΔL-bound stopped filaments was determined over a range of actin oligomer concentrations and expressed as mean ± SD, n=3. (I) Kymographs of growing and stopped SNAP-EnaΔL-bound filaments in the presence of 5 nM of actin oligomers. See also Movie S7.

(J–O) Effects of actin oligomers on Ena-mediated actin polymerization in the presence (J,M) or absence of PFN1 (K,N) with oligomers added at the start of polymerization (J,K) or at the time point when ~15% of actin was polymerized (M,N; red arrows). (L,O) Inhibition of Ena-controlled actin polymerization as determined from triplicates of (J,K) and (M,N), respectively; data is mean ± SD (see STAR Methods). See also Figure S1B.

Actin oligomers convert Ena/VASP into a capping protein

To test whether the effects observed in living cells could be mediated via direct inhibition of Ena/VASP activity by the ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers, we characterized the oligomer’s interaction with EnaΔL, the Drosophila homolog of VASP lacking a poorly conserved linker of unknown function (Figure 4E; [23]). In TIRFM, actin oligomers caused long pauses in elongation of Ena-bound, but not Ena-free filaments (Figures 4F–I; Movie S7). In bulk polymerization assays, the apparent dissociation constants of the Ena-oligomer complexes (appKd values) were 3.7 and 3.2 nM in the absence or presence of profilin, respectively (Figures 4J–L). These numbers were similar to those obtained by mathematical modeling (Kd = 2 nM; Figure S1B) and comparable to those for formins [13], suggesting that the two classes of molecules can be inhibited with similar efficiencies.

When added after the initiation of Ena-assisted polymerization, the oligomers caused a very similar inhibition (Figures 4M–O), suggesting their strong binding to filament-associated Ena. This observation is further corroborated by the TIRFM and bulk polymerization findings that saturating concentrations of the oligomers inhibited actin polymerization well below its spontaneous levels, suggesting that the complexes of EnaΔL with the oligomers function as potent capping proteins tightly associated with filament barbed ends. At high oligomer concentrations (>75 nM), a reversal of the inhibition was observed, which could be modeled by: 1) oversaturation of free Ena by oligomers, inhibiting its association with barbed ends; and 2) incorporation of the oligomers into polymerizing filaments leading to increased fragility and severing [13].

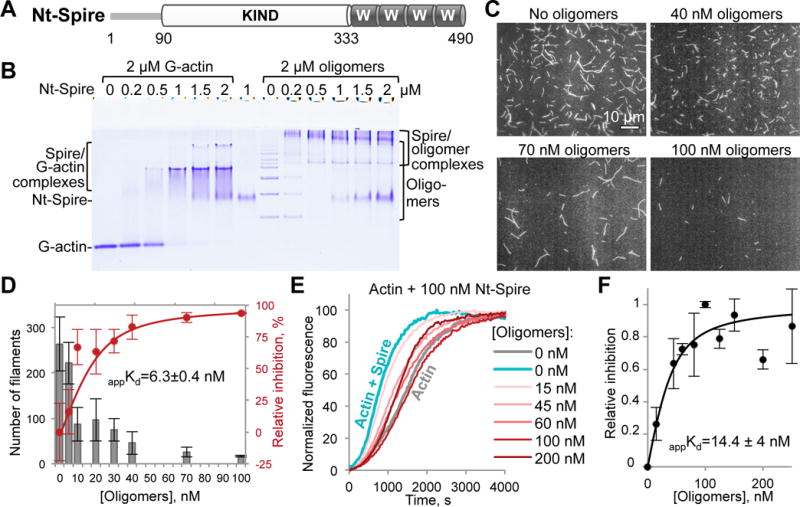

Oligomers inhibit Spire-mediated actin nucleation

In addition to NPFs and Ena/VASP, tandem WH2-domains are found in a distinct family of actin nucleators that include Spire, Cobl, and several bacterial toxins [15]. The N-terminal fragment of Spire, Nt-Spire (Figure 5A), which retains the nucleation activity of the full-length protein [24], binds to the oligomers as revealed by native electrophoresis (Figure 5B). Higher order oligomers were depleted by low concentration of Spire suggesting their higher affinity to the nucleator. Data from TIRFM and bulk actin polymerization assays converged to similar inhibition efficiencies in a nanomolar range (appKd values of 6.3 and 14.4 nM), suggesting multivalent high-affinity interactions between Spire and the oligomers (Figures 5C–F). In bulk polymerization assays, high doses of the oligomers caused acceleration of polymerization, in agreement with the previously proposed and modeled mechanism of increased filament fragility upon infrequent inclusion of the oligomers into the filament [13]. As with other proteins, mathematical modeling of Spire inhibition by the oligomers produced good fits at low concentrations of oligomers with Kd=5 nM. The fit was less satisfactory at oligomer concentrations near 100 nM, at which the heterogeneity of the oligomeric species and the above mentioned filament fragility, whose behavior is highly prone to experimental fluctuations, become important and difficult to accurately model (Figure S1C).

Figure 5. Inhibition of Spire-mediated actin nucleation by the actin oligomers.

(A) Domain organization of the Nt-Spire construct corresponding to the N-terminal part (a.a. 1-490) of drosophila Spire: KIND, kinase non-catalytic c-lobe domain, W, WH-2-domain.

(B) A representative native gel (n=3) of G-actin and ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers titrated by Nt-Spire. Formation of complexes is indicated by the appearance of bands of lower electrophoretic mobility as compared to the individual protein bands.

(C,D) Single-color TIRFM images (C) taken at 8 min of polymerization of Alexa 488-actin in the presence of 20 nM Nt-Spire and various concentrations of the oligomers, as indicated. (D) Number of actin filaments formed in (C) was quantified from three independent experiments, expressed as mean ± SE (grey bars), and used to generate a relative inhibition curve (red) and obtain an apparent Kd (appKd) as described in STAR Methods.

(E,F) Nucleation of pyrene-actin by Nt-Spire was inhibited by the indicated concentrations of the oligomers in bulk actin polymerization assay (E; see also Figure S1C). Inhibition of the Spire-mediated actin nucleation by the oligomers (F) was assessed from three independent experiments, expressed as mean values ± SD, and the apparent Kd value (appKd) was calculated as described in STAR Methods.

See also Movie S8.

Upon transfection of XTC cells with human EGFP-tagged full length or Nt-Spire, both constructs were localized at the leading edge of the cells and appeared to be associated with the retrograde flow of actin filaments (Movie S8). The association with the actin flow was transient, however, as most speckles can be traced for no longer than a few seconds, making it difficult to carefully evaluate their flow rate (41 ± 8 nm/s; n=5; Movie S8). Spire can associate with the minus ends of actin filaments upon their nucleation [25, 26], with the plus ends upon positive and negative cooperation with other proteins [27, 28], and even with sides on the filament leading to their severing [24]; but which of the three events, or all, we observed in XTC cells is not clear. ACD decreased the number of observable speckles (Movie S8) likely owing to dissociation of EGFP-Nt-Spire from F-actin as only fluorescent proteins associated with large cellular structures (e.g., actin cytoskeleton) have a “speckled” appearance in SiMS as opposed to a blurred appearance of rapidly diffusing free proteins.

DISCUSSION

The actin cytoskeleton is a highly attractive target for many bacterial toxins owing to its role in activation and locomotion of immune cells, secretion of humoral response factors, maintenance of protective barriers at the cellular (sub-membrane cytoskeleton) and organ (cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts) levels. Furthermore, due to the low homology between eukaryotic actin and its bacterial counterparts, actin-targeting toxins are highly specific against hosts, but benign for pathogens. On the other hand, the actin cytoskeleton would not appear to be an easy target due to actin’s high abundance and the cells’ ability to promptly adjust its levels in response to environmental [29] and pathogenic cues [30].

In this study, we combined the precision and predictive power of biochemical assays, substantiated by mathematical modeling, with the quantitative analysis of the actin cytoskeleton dynamics in living cells achieved via single-molecule speckle (SiMS) microscopy, to characterize the pathological mechanisms of the ACD family of toxins. These approaches allowed us to discover that the distortion of the actin cytoskeleton by the ACD-produced oligomers is more profound and multifaceted than previously appreciated. Particularly, the dynamics of mDia1 formin (Figure 3) was severely inhibited at concentrations of the oligomers undetectable by western blotting (i.e., estimated to be below 1% of total actin (Figure 1B)) within 30 min of toxin addition to the medium, long before any morphological changes in the affected cells can be detected (Figure 1A). In addition to formins, several families of actin assembly factors containing WH2-domains were also inhibited by the nanomolar range of oligomer concentrations. The emergence of cellular effects for particular proteins correlated well with the in vitro data from TIRFM and bulk actin polymerization assays. Thus, cellular dynamics of mDia1 formin and Ena/VASP, which showed the highest apparent affinities for oligomers in functional assays (appKd 2–5 nM for formins [13] and 3–6 nM for Ena/VASP (Figure 4)), were inhibited at earlier stages than that of the Arp2/3 complex, activation of which by N-WASP was inhibited in vitro with lower efficiencies (appKd in 10–23 nM range; Figure 2O). This lower potency likely stems from a fewer (than in formins and Ena/VASP) number of G-actin binding domains and, possibly, a less favorable geometry for oligomer binding to NPFs. Of note, depending on the involvement in a particular cellular process (i.e., remodeling of cytoplasmic [31], endosomal [32], autophagosomal [33, 34], Golgi and ER membranes [35, 36], or contribution to cytoplasmic streaming [37], etc.), the Arp2/3 complex can be activated by different NPFs, of which only two were tested in the present study: VCA fragment of N-WASP in the in vitro assays (Figures 2G–O) and WAVE in the cellular context (Figures 2D–F). Given that the oligomers interact with NPFs rather than with the Arp2/3 complex (Figure 2H), the inhibition efficiency of the complex-controlled actin dynamics would likely vary by NPF, proportional to the number of G-actin binding domains they comprise. Thus, JMY, an NPF that regulates transcription in the nucleus and vesicle trafficking between the ER and trans-Golgi network [38-40], with its three WH2-domains, is likely to be inhibited more efficiently than N-WASP and WHAMM (each containing two WH2-domains), which regulate endocytosis [41] and autophagosome formation [33], respectively. Furthermore, all these NPFs are likely to be more efficiently inhibited than single WH2-domain NPFs WASP, WAVE, and WASH, which are involved in endocytosis, cell migration and endosomal trafficking (recently reviewed in [31]). Notably, inhibition of many of these processes would be beneficial for pathogenic bacteria to interrupt migration, phagocytosis, and activation of immune cells, disrupt epithelial contacts, inhibit Golgi-dependent maturation of granules in immune effector cells and their release, and inhibit autophagy.

By promoting bundling and processive elongation of actin filaments, and inhibiting association of capping protein with filament barbed ends, Ena/VASP family proteins contribute to the dynamics of lamellipodia and filopodia [42] and maintenance of focal adhesions and tight junctions [43, 44]. Accordingly, shortly after cytoplasmic delivery of ACD, we observed ceasing of VASP dynamics at the leading edge (Figures 4B and C), major inhibition of filopodia formation, and VASP disconnection from the paxillin-marked focal adhesion contacts and actin stress fibers, accompanied by its partitioning into smaller clusters (Figure 4D). In cell contacts, Ena/VASP is an essential element of the mechanosensory machinery, enabling dynamic adjustments of actin filament lengths at the tips of contact-associated stress fibers [43, 44]. Dissociation of VASP coincided with the disruption of focal adhesion contacts to less organized, smaller aggregates that were poorly associated with actin stress fibers (Figure 4D). Given the highly promiscuous binding abilities of the oligomers, it is conceivable that in such aggregates VASP is linked by the oligomers to other multivalent actin-binding proteins (e.g., NPFs, formins, and Spire [42, 45-47]) that often function within proximity of each other. Inhibition of Ena by the oligomers and disruption of VASP-containing structures suggests that the previously reported drop in epithelial integrity [13] may be mediated not only by inhibition of formins, but also of Ena/VASP proteins.

To summarize, we demonstrated here that actin oligomers produced by ACD toxins from Vibrio and related bacterial species overcome an overabundance of their natural target (actin) and potently disrupt numerous actin-related processes by acting as universal multivalent inhibitors of oligomeric and tandem-organized G-and F-actin binding proteins.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dmitri S. Kudryashov (kudryashov.1@osu.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell culture

The XTC fibroblasts from Xenopus laevis is a convenient model for live-cell imaging at the single-molecule level due to their tolerance to photo-damage accompanying image acquisition [48, 49]. XTC cells were cultured in 70% Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin at 23°C without CO2 equilibration and confirmed to be mycoplasma-negative using Hoechst staining and fluorescence imaging. The cell line was obtained from Dr. Naoki Watanabe (Kyoto University, Japan) and has not been additionally authenticated.

METHOD DETAILS

Cellular actin cross-linking by ACD

For the intracellular delivery of ACD, the Anthrax toxin (Atx) translocation system was used [50, 51]. The approach utilizes the protective antigen (PA) subunit of Atx, which, upon interaction with the Atx receptor present on the surface of many cell types, forms hexa- and heptamers. Oligomerization of PA drives interaction with another Atx component, lethal factor (LF), and internalization of the complex by endocytosis. The acidification of the endosome causes the PA oligomer to form a pore in the endosomal membrane, through which LF translocates into the cytosol. Importantly, non-enzymatic N-terminus of LF (LFN) being fused to a toxin of interest (e.g., LFNACD; [12, 13]) confers the toxin delivery to the cytosol.

To this end, PA and Vibrio cholerae ACD fused to LFN (LFNACD) were purified as previously described [13, 52]. XTC cells were treated with LFNACD pre-mixed with PA (final concentrations: 1 nM LFNACD, 2.5 nM PA). A catalytically inactive LFNACD mutant EE1990/1992AA [13, 53] was used as a negative control. Following cell imaging at designated time points, cells were collected for western blotting. Accumulation of ACD-cross-linked actin species in XTC whole cell lysates was monitored by immunoblotting with pan-actin antibody ACTN05(C4) (1:1000; ThermoFisher Scientific) folllowed by anti-mouse antibody conjugated with HRP (1:10000; Sigma); signal was detected using chemiluminescent HRP substrate WesternBright Sirius (Advansta) in an Omega Lum G imager (Aplegen). The accumulation of ACD-cross-linked actin species was quantified from three independent replicates using a densitometry plug-in of the ImageJ software package [54].

Live-cell single-molecule speckle (SiMS) microscopy

EGFP-constructs under defective CMV promoter optimized for low levels of expression of fluorescent proteins [48] were a generous gift from Dr. Naoki Watanabe [17, 20, 22, 48, 49], except for human full-length Spire and Nt-Spire (corresponding to a.a. 1-396), which were amplified by PCR from HeLa cells cDNA and cloned into EGFP-vector with the defective CMV promoter. Transfections of XTC cells were performed using TurboFect transfection reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific). The following day, cells were trypsinized and replated to minimize cell damage after transfection. For SiMS analysis, transfected cells were plated onto poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips (NeuVitro GG-25-1.5-PDL) in Attofluor cell chambers (ThermoFisher Scientific) and imaged using TIRF module on Nikon Eclipse Ti-E inverted microscope equipped with perfect focus system (Nikon) and iXon Ultra 897 EMCCD camera (Andor Technology). Photo damage to cells was minimized by restricting the illumination (10% of laser power) to a small area near the cell membrane using a field diaphragm. Cells expressing very low levels of EGFP-tagged proteins of interest suitable for SiMS [48] were identified and selected for imaging. Active or inactive LFNACD pre-mixed with PA (final concentrations: 1 nM LFNACD, 2.5 nM PA) were added to the cell chamber and sets of time-lapse images of the same area of an individual cell were taken every 15 min of the ACD treatment with different intervals for each construct: for human β-actin, X. laevis p40, and human Nt-Spire time-lapse images were taken for the duration of 3 min with 1 s intervals; for mouse mDia1ΔdN3 - for 45 s with 0.21 s intervals; for X. laevis WAVE - for 1 min with 0.25 s intervals; for X. laevis VASP - for 2 min with 0.5 s intervals. Single-molecule speckles trajectories were analyzed by Fiji/ImageJ software using Manual tracking TrackMate plug-in [55]. For EGFP-actin, p40, and mDia1ΔN3, trajectories of 8–23 directionally moving speckles (tracks) encompassed 80–350 individual spot displacement events were analyzed and average displacement and velocities were calculated and plotted using BoxPlotR software [56]. On the box plots, center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles; data points are plotted as circles. Average intensity projections and kymographs of time-lapse images were obtained using ImageJ Z-project and KymographBuilder plug-ins, respectively. For each construct, movie montages (Movies S1-3, S5, S6, and S8) showing a fragment of the same cell at various time points of ACD treatment were assembled using Multi Stack Montage plug-in. Cell edge dynamics was quantified using ImageJ by calculating the area change normalized to an initial cell edge length in four individual cells. To this end, the area enclosed between the cell contour lines at the beginning (0 s) and at the end (60 or 120 s) of measurement periods for each ACD treatment condition was determined and divided by the initial contour length at 0 s.

Immunofluorescence

EGFP-VASP-transfected XTC cells were treated for 60 min with either active or inactive LFNACD pre-mixed with PA as above, fixed with 4% paraformaldehide, permeabilized with 0.1% of Triton X-100 in PBS, stained with anti-paxillin (Bethyl), contra-stained with coumarin-phalloidin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and imaged using Nikon Eclipse Ti-E microscope.

Protein purification

Protective antigen

B. anthracis PA was purified as previously described [52]. Briefly, protein was expressed in BL21(DE3)pLysS by IPTG induction for 4 h at 30°C. PA was purified from the periplasmic fraction on DE52 anion exchange resin (Sigma-Aldrich).

LFNACD

LFN fusions of active ACD from V. cholerae, and its catalytically inactive mutant EE1990/1992AA (V. cholerae MARTX numbering; [53]) were purified as reported [13]. Expression in BL21(DE3)pLysS was induced by IPTG overnight at 15°C and proteins were purified using TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech) according to the manufactorer instructions.

Actin

Skeletal actin was prepared from acetone powder of rabbit (Pel-Freeze Biologicals) or chicken (Trader Joe’s) skeletal muscle with no detectable differences in protein properties as previously described [57] using G-buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM ATP, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol [β-ME]) and multiple rounds of polymerization and depolymerization. Alexa 488-, tetramethylrhodamine-(TMR), and pyrene-labeled actins were prepared as previously described [13] from G-actin in G-buffer devoid of β-ME. Alexa 488-actin was prepared by labeling 2 mg/ml G-actin with 1.2 molar excess of Alexa Fluor 488-maleimide (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 4 h at 4°C, followed by dilution to 1 mg/ml and polymerization with 2 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM KCl overnight at 4°C. Pryrene-actin was prepared by polymerizing 2 mg/ml G-actin with 2 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM KCl at 25°C for 30 min and then diluted to 1 mg/ml in F-buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl). N-(1-pyrene)Iodoacetamide (ThermoFisher Scientific) was added to a final concentration of 40 µM and the labeling was carried out overnight with mixing at 4°C. Both, Alexa 488 and pyrene labeling were quenched with 10 mM β-ME and labeled actins were pelleted at 45,000 rpm in Ti-60 (Beckman Courter) for 90 min followed by three rounds of dialysis of the resulted pellets against G-buffer. TMR-actin was prepared by labeling 2 mg/ml G-actin with 1.5 molar excess of TMR-maleimide (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 4 h at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 85,000 rpm for 30min in TLA100.3 rotor (Beckman Courter). To remove free TMR-maleimide, TMR-actin supernatant was passed through PD10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with G-buffer containing β-ME. All labeled and unlabeled G-actins were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography on Sephacryl S200-HR (GE Healthcare), stored on ice in G-buffer and used within 4 weeks with a dialysis to G-buffer after two weeks of storage.

ACDAh

Thermolabile ACD from Aeromonas hydrophila (ACDAh) was purified as previously described [58]. Expression in BL21(DE3)pLysS was induced by IPTG overnight at 15°C and ACDAh was purified using TALON metal affinity resin by standard procedure.

ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers

Actin oligomers were prepared by mixing 20 µM G-actin with 10 nM ACDAh in reaction buffer (5 mM HEPES, 0.2 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2) at 10°C for 25 min. The reaction was terminated by heat-inactivation of ACDAh at 42°C for 20 min. To polymerize uncross-linked actin, the concentration of MgCl2 was then increased to 3 mM and the reaction was incubated at 25°C for 30 min. F-ac tin was pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 90,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C in a TLA100 rotor (Bec kman Coulter). The supernatant was supplemented with 1 mM ATP and the concentration of monomeric actin in cross-linked species was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) using monomeric actin as a standard without correcting for the heterogeneity of actin oligomer species. Inactivation of ACD and removal of uncross-linked actin were confirmed as described [13]. ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers were stored on ice and used within 7 days.

EnaΔL

A recombinant construct of Drosophila melanogaster Ena protein lacking a linker region (a.a. 113-299; Figure 4E) and SNAP-tagged EnaΔL were prepared as previously described [23]. Briefly, proteins were purified using TALON cobalt resin (Clontech) in buffer A (50 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, and 0.5 mM PMSF), eluted in buffer B (buffer A supplemented to 250 mM imidazole), and stored in buffer C (20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 200 mM KCl, 5 mM β-ME, 10% glycerol, and 0.1 mM PMSF). Labeling with SNAP-surface 549 (NEB) was conducted using standard procedure [19].

Nt-Spire

A construct corresponding to the N-terminal part (a.a. 1-490) of D. melanogaster Spire (Figure 5A) was purified as previously described [59] using TALON metal affinity resin by standard procedure and stored in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 2 mM DTT, and 50% glycerol.

N-WASP-VCA

GST-tagged construct corresponding to the C-terminal part (a.a. 422-505) of bovine N-WASP (Figure 2G), and murine C-terminally 6xHis-tagged N-WASP-VCA (a.a. 399-501) (Figure 2I) were purified on glutathione sepharose (GE Healthcare) and TALON cobalt resin (Clontech), respectively, using standard methods [19, 60]. The latter construct contained an exogenous N-terminal Cys residue used for labeling with fluorescein-5-maleimide (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Arp2/3 complex

The Arp2/3 complex was purified from porcine thymus (Pel-Freeze Biologicals) as described [61]. Briefly, thymus was thawed and passed twice through a meat grinder in extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, 1 mM PMSF, 0.002 g/mL leupeptin/pepstatin, 0.002 m/mL trypsin inhibitor, 4 mM benzamidine). The extract was stirred for 30 min at 4°C, clarified by centrifugation, and filtered through synthetic wool (Pyrex). Potassium hydroxide was then added to adjust the final pH to 7.5 and the sample was further clarified by centrifugation. The Arp2/3 complex was applied on glutathione sepharose resin with pre-bound GST-tagged N-WASP-VCA. The resin was then extensively washed with the extraction buffer followed by successive washes of 10 column volumes with buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.1 mM PMSF), buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 100 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.1 mM PMSF), and buffer 3 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 M KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.1 mM PMSF). Purified Arp2/3 complex was dialyzed for 16 h at 4°C into storage buffer (10 mM imidazole pH 7, 25 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein concentration was determined using the extinction coefficient ε290 = 139,000 M−1cm−1 [62].

Profilins

Human profilin-1 (PFN1) and drosophila profilin (chickadee) were purified as previously described [13, 23]. PFN1 was bound to a poly-L-proline sepharose resin, eluted under denaturing conditons, and dialyzed against three buffer changes of storage buffer (2 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF).

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)

For native PAGE analysis, proteins of interest were pre-incubated in G-buffer at 25°C for 30 min, mixed with a non-reducing, non-denaturing sample buffer, and immediately loaded to 9% native PAGE gels devoid of SDS and supplemented with 0.2 mM Ca2+ and 0.2 mM ATP (for actin stability). The native PAGE running buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 192 mM glycine) was supplemented with 0.2 mM Ca2+ and 0.2 mM ATP, and the gels were electrophoresed at 4°C.

Fluorescence polarization

Fluorescein-labeled N-WASP-VCA (50 nM) in G-buffer was titrated with increasing concentrations of G-actin or ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers. Fluorescence polarization was recorded at λex = 470 nm and λem = 519 nm on an Infinite M1000 Pro plate reader (Tecan).

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM)

All TIRFM experiments were performed as previously described [13, 63]. Briefly, Alexa 488- or TMR-labeled skeletal actin (final concentration 1.5 µM; 33% labeled) in G-buffer was supplemented with 0.1 mM Mg2+ and 0.4 mM EGTA and incubated for 2 min. Actin was added to actin-binding proteins and ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers in the following buffer: 10 mM imidazole, 50 mM KCl, 50 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM ATP, 50 μM CaCl2, 15 mM glucose, 20 g/mL catalase, 100 g/mL glucose oxidase, 3% glycerol, and 0.5% methylcellulose-400cP (Sigma Aldrich), pH 7. For the Arp2/3 complex and Spire experiments, samples were flowed into NEM-myosin-treated flow chambers immediately upon mixing [13]. Images were collected every 5 seconds with TIRF illumination using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E microscopes equipped with DS-QiMc camera (Nikon). For two-color TIRFM, Alexa 488-actin (1.5 µM; 33%) was mixed with Arp2/3 (40 nM) and GST-N-WASP-VCA (80 nM) in the absence or presence of actin oligomers (320 nM) and polymerized in the NEM-myosin-treated flow chamber. TMR-actin (1.5 µM; 33%) was flowed into the chamber alone, with oligomers, or with Arp2/3-N-WASP-VCA complex, replacing the Alexa 488-actin and the partner proteins. For SNAP-EnaΔL single-molecule TIRFM experiments, the protein mixtures with Alexa 488-labeled actin (1.5 µM; 15%) were flowed into mPEG-Silane (5,000 MW) coated flow chambers and images were collected every second with an iXon EMCCD camera (Andor Technology) using an Olympus IX-71 microscope fit with through-the-objective TIRF illumination. In both settings, filaments were manually tracked and measured using ImageJ software.

Pyrenyl-actin polymerization assays

Actin polymerization assays were carried out as previously described [13]. Briefly, pyrene-labeled, gel-filtered Ca2+-actin (5% labeled; 2.5 µM final concentration) was pre-incubated with EnaΔL, Nt-Spire, or GST-N-WASP-VCA and Arp2/3 complex in the presence or absence of profilin and varying concentrations of actin oligomers (0–750 nM) in reaction buffer (10 mM MOPS pH 7.0, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT). Ca2+-ATP actin was then converted to Mg2+-ATP actin by the addition of 0.066 volumes of switch buffer (150 mM MOPS pH 7.0, 3 mM ATP, 7.5 mM DTT, 4.5 mM EGTA, 1.5 uM MgCl2) and incubation for 2 min. Polymerization was initiated by the addition of 0.33 volumes of initiation buffer (30 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 0.6 mM ATP, 1.5 mM DTT, 3 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl) and monitored at λex = 365 nm and λem = 407 nm on an Infinite M1000 Pro plate reader (Tecan).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Quantification

Relative inhibition of Nt-Spire by oligomers in TIRFM experiments

In Nt-Spire TIRFM experiments, number of forming filaments was counted and relative inhibition of Spire-mediated nucleation by oligomers was calculated as:

| (1) |

where I – relative inhibition, CX – number of filaments formed in the presence of Spire at a given oligomers concentration, and C0 – number of filaments formed in the presence of Spire without actin oligomers. The relative inhibitions were then fit using Origin software (OriginLab) to the binding isotherm equation:

| (2) |

where I – relative inhibition, Imax – maximum change in inhibition, P – concentration of functional units of a protein of interest (i.e., Nt-Spire in this case), X – concentration of cross-linked actin oligomers, K – the apparent inhibition constant (appKd).

Relative inhibition of actin-regulating proteins by oligomers in bulk pyrene-actin polymerization assays

Inhibition of EnaΔL-mediated polymerization by actin oligomers was assessed by determining the tangent slope of each fluorescence trace at 50% of fluorescence maximum (slope from 40–60%) and fitting the slopes to a binding isotherm (Equation 2), where I – the observed change in the tangent slope at 50% of fluorescence maximum and Imax – the maximal change in slope from pyrene fluorescence trace of EnaΔL-mediated actin polymerization in the absence of oligomers (with or without PFN1) in each independent experiment.

Inhibition of Spire-mediated actin nucleation by the oligomers was measured as described [64]. Briefly, the points from 5–20% maximal fluorescence of each pyrene fluorescence trace were fit to a quadratic equation:

| (3) |

where A is dependent upon the nucleation rate, B is dependent upon the number of barbed ends and C is dependent upon the concentration of filamentous actin. By using initial points where few filaments have formed, the values for B and C are considered equal to zero. The nucleation rate (NR0) is then determined using the following equation:

| (4) |

where k+ is the rate at which the barbed ends of rabbit actin elongate at room temperature (11.6 μM−1s−1), k− is the rate at which rabbit actin shrinks at room temperature (1.4 s−1) [65]; A is determined from the Equation 3, [Actin]0 is the initial concentration of actin monomers, which is a good approximation for the amount of free monomeric actin in solution during the initial time of polymerization measured; SF is the actin filament concentration scaling factor determined by subtracting the critical concentration of actin polymerization (0.1 μM) from [Actin]0 and dividing by the total fluorescence change. Obtained nucleation rate data was fit to the Equation 2, where I is the observed change in the nucleation rate in the presence of oligomers subtracted from that of Spire in the absence of oligomers, Imax – the maximal change in nucleation rate in the presence of oligomers subtracted from that of Spire alone in each independent experiment.

For the N-WASP-VCA-activated Arp2/3 nucleation of actin, inhibition was measured by calculating the time to half-maximal fluorescence and fitting the obtained data to the binding isotherm (Equation 2), where I is the observed change in the time to half maximal fluorescence in the presence of oligomers subtracted from that of N-WASP-VCA-activated Arp2/3 in the absence of oligomers (in the presence or absence of PFN1), Imax – the maximal change in the time to half maximal fluorescence in the presence of oligomers from that of N-WASP-VCA-activated Arp2/3 in the absence of oligomers (in the presence or absence of PFN1) in each independent experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data from in vitro TIRFM, fluorescent polarization, and pyrene actin polymerization assays were obtained from at least three independent experiments and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SD). Fraction of cross-linked actin was quantified and expressed as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SE) from three independent replicates of the cell lysate immunoblots stained for pan-actin. For live-cell SiMS analysis of each studied construct, transfections followed by the ACD-treatment were repeated three times with similar results. Cell edge dynamics was quantified in four individual cells for each condition. Speckle analysis was conducted for an individual cell in each experiment for all time points to ensure the identical conditions and to assess the effects of the ACD toxicity in real time. Unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine statistical significance using Microsoft Excel and Origin software. Differences were considered significant with a p-value < 0.05. There were no data exclusions and the minimum sample size was chosen to satisfy the requirement for differences between the conditions to be highly significant (i.e., p-values are much less than 0.05).

Modeling of actin filament nucleation and elongation in the presence of actin oligomers

We developed ordinary differential equations models to describe actin polymerization with the Arp2/3 complex, Ena/VASP, or Spire in the presence of oligomers (Figure S1, Table S1). These models provide support for the proposed inhibition mechanisms as well as estimates of oligomer binding affinities to their targets. We focused on the mechanisms in the absence of profilin.

All models include spontaneous nucleation and elongation of actin filaments involving the formation of a trimer [66] with rate constant determined by fitting the model results in the absence of oligomers to experiments [13]. Free actin filament elongation at the barbed end occurs with rate constant . We neglect the pointed end and actin filament depolymerization. Thus, we do not account for the final presence of ~ 0.1 μM of unpolymerized actin out of the total Atot = 2.5 μM used in the experiments in the absence of profilin.

Oligomers are assumed to incorporate at free barbed ends at concentration B with rate constant . Polymerized oligomers induce severing, resulting in the formation of a new barbed end, with rate constant . Including this reaction leads to better fits to the experimental curves, depending on the value of the product [13]. Spontaneous filament fragmentation with rate k frag of order the value estimated in prior works [67, 68] improves the fits to the data at long times [13].

The parameter values for all models are shown in Supplemental Table S1. The equations were integrated numerically with the Euler-Richardson integration scheme with a time step 0.5 sec or smaller. The results in the graphs of Supplemental Figure S1 report the polymerized fraction, (Atot − Aunpol)/Atot, versus time, where Aunpol is free actin.

Oligomer inhibition of Arp2/3 complex nucleation

The side-branch nucleation complex that involves the Arp2/3 complex, VCA and actin monomers on the side of a mother filament can form via multiple pathways [18, 69-71]. Here we focus on one pathway that is sufficient for a good fit to the data in this paper. We assumed that free Arp2/3 complex binds to GST-tagged N-WASP-VCA dimers with dissociation constant . This is followed by binding of one and then two actin monomers to form Arp2/3-VCA-actin1 and Arp2/3-VCA-actin2 complexes, each with . We used binding affinities and association/dissociation rate constants for these processes from prior work [70]. Arp2/3 complex nucleates daughter filaments with low probability per mother filament association [71], a process that we represent with a rate proportional to the concentrations of the Arp2/3-VCA-actin2 complex and F-actin, with rate constant k branch. VCA was assumed to fall off the nucleated branch, though our results do not depend on this assumption. The branching rate constant was fit to match the polymerization curve in the absence of oligomers. Finally, we assume oligomers bind to Arp2/3-VCA or Arp2/3-VCA-actin1 with resulting in complexes that do not participate in branch formation.

The Arp2/3 complex may also nucleate new barbed ends at a slow rate without a mother filament [70]. However this process is slow for the concentrations of Arp2/3 complex used in this work and not needed for a good fit; hence we did not include this reaction in the model.

The following differential equations together with mass conservation describe the evolution over time, where: k indicates rate constants; the concentrations of free Arp2/3 complex, VCA and their complexes are Arpfree, VCAfree, ArpVCA, ArpVCAactin1, ArpVCAactin2, ArpVCAO, ArpVCAactinO, where O indicates oligomers; concentrations of free and polymerized oligomers by Ofree and Opol:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

We find that good fits to the data is obtained with (Figure S1A, Table S1). The oligomer-induced severing rate (product ) had to be lower compared to the values used in our prior model of oligomers in the presence of formins [13]. This may indicate the reduced severing of a branched network as opposed to severing of individual single filaments.

Oligomer inhibition of Ena-mediated nucleation and elongation

To model polymerization in the presence of EnaΔL we considered binding of EnaΔL tetramers to free barbed ends with a dissociation constant in the subnanomolar range, and dissociation rate of order 0.1 s−1 [23]. Ena-associated barbed ends were assumed to polymerize actin three times faster than free barbed ends [23]. Ena/VASP has been observed to nucleate actin filaments using the pyrene actin polymerization assay in vitro, even though this is not a property expected to occur in vivo [21]. We adjusted a nucleation rate constant to fit the polymerization curve in the presence of EnaΔL, assuming the nucleus is a complex of one Ena and two actin monomers.

Oligomers slow down Ena-mediated polymerization beyond that of actin alone, indicating conversion of Ena to a capper. We thus incorporated in the model the binding of an EnaΔL tetramer to an oligomer in the bulk with equilibrium dissociation constant . The oligomer-Ena complex can bind to the barbed end with , blocking polymerization. From detailed balance, binding of oligomers to an Ena-bound barbed end occurs with . Another feature of the pyrene polymerization curves in the presence of Ena and oligomers is the acceleration of polymerization as the concentration of oligomers increases above 50 nM. We modeled this effect as being due to the binding of up to four oligomers to EnaΔL tetramers in the bulk. We assume that complexes with two bound oligomers associate with the barbed end, similar to complexes with one bound oligomer and satisfying a similar detailed balance condition; by contrast, complexes with three or four bound oligomers do not associate to the barbed end, thus sequestering EnaΔL-oligomer cappers in the bulk at high oligomer concentrations.

The following differential equations together with mass conservation describe the evolution of concentrations over time, where: concentrations of bulk free Ena and its complexes with oligomers are Enafree, EnaO, EnaO2, EnaO3, EnaO4; concentration of Ena-bound barbed ends are BEna, BEnaO, BEnaO2; concentrations of free and polymerized oligomers Ofree and Opol; ratios of dissociation and association rate constants correspond to the equilibrium dissociation constants defined above:

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

In Equations (19-22) we assume the binding rate constant of oligomers to Ena-oligomer complexes in the bulk is reduced with increasing size of the complex (Table S1). The rate constants of oligomer dissociation from Ena in the bulk increase in proportion to the number of bound oligomers. These two trends correspond to an increase of the equilibrium oligomer dissociation constant with increasing number of Ena-bound oligomers. It is the value of this dissociation constant and not the value of the individual bulk rate constants that matter in the simulated curves.

The above equations describe the qualitative and most quantitative features of the experimental data using , an affinity of oligomers for an Ena-bound barbed ends close to the value estimated in Fig. 4L,O, and an affinity of Ena-oligomer complex to the barbed end similar to Ena tetramer alone, (Figure S1B, Table S1). The dissociation constant of Ena bound to two oligomers to the barbed end was . The observed behavior involves three regimes: (1) speed-up of polymerization by Ena (compared to pure actin), (2) reduction of Ena-mediated polymerization below that of pure actin with increasing oligomer concentration up to 50 nM, (3) speed-up of polymerization with oligomer concentrations above 50 nM, still remaining below that of pure actin. The simulations reproduce these three regimes. We note that the rate constants describing complexes of Ena with multiple oligomers cannot be uniquely determined by the fits.

Oligomer inhibition of Spire-mediated nucleation

We simulated the effects of Spire by assuming it contributes to filament nucleation through a complex of two Spire and four actin monomers, with rate constant (a model with a single Spire as nucleator gave similar though somewhat worse fits). Nucleated filaments are assumed to polymerize as filaments with free barbed ends and Spire is assumed to fall off the pointed end of the nucleated filament. Oligomers inhibit nucleation by binding to and inactivating Spire with dissociation constant . The following equations and mass conservation describe the evolution of concentrations over time, where Spirefree and Spiretot are concentrations of free and total Spire; Otot, Ofree and Opol are concentrations of total, free and polymerized oligomers:

| (23) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

Free oligomers in the solution are assumed to bind to and dissociate from Spire according to an equilibrium second-order reaction:

| (26) |

with

Good agreement with experimental data is found using (Figure S1C, Table S1).

Supplementary Material

A multi stack montage of time-lapse images of a peripheral region of an individual XTC cell expressing low levels of EGFP-actin and treated with either active ACD (upper row) or inactive ACD (lower row).

A multi stack montage of time-lapse images of a peripheral region of an individual XTC cell expressing low levels of EGFP-p40 (an Arp2/3 subunit) and treated with either active ACD (upper row) or inactive ACD (lower row).

A multi stack montage of time-lapse images of a peripheral region of an individual XTC cell expressing low levels of EGFP-WAVE (a type I NPF) and treated with either active ACD (upper row) or inactive ACD (lower row).

Movies show time-lapse images of polymerization of Alexa 488-actin (1.5 µM) mixed with the Arp2/3 complex (20 nM) and GST-N-WASP-VCA (40 nM) in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 80 nM ACD-cross-linked actin oligomers.

A multi stack montage of time-lapse images of a peripheral region of an individual XTC cell expressing low levels of EGFP-mDia1-ΔN3 and treated with either active ACD (upper row) or inactive ACD (lower row).

A multi stack montage of time-lapse images of a peripheral region of an individual XTC cell expressing low levels of EGFP-VASP and treated with either active ACD (upper row) or inactive ACD (lower row).

Movies show time-lapse images of polymerization of 1.5 µM Alexa-488-actin (green) in the presence of 0.5 nM SNAP-EnaΔL (red), 3 µM chickadee, and 5 nM actin oligomers. Open arrowheads denote unbound barbed ends, green filled arrowheads show growing Ena-bound ends (left panel), and a red filled arrowhead is for a stopped Ena-bound end (right panel).

A multi stack montage of time-lapse images of a peripheral region of an individual XTC cell expressing low levels of EGFP-Nt-Spire and treated with either active ACD (upper row) or inactive ACD (lower row).

Highlights.

ACD toxin is a potent universal inhibitor of various actin assembly factors

In live cells, ACD toxin stalls dynamics of formins, Ena/VASP, Spire, and NPFs

ACD toxicity is amplified by redirecting from actin to less abundant targets

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Naoki Watanabe (Kyoto University) for a generous gift of XTC cells and the plasmids encoding EGFP-fusion proteins of actin, p40, mDia1ΔN3, WAVE, and VASP. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under award numbers R01 GM114666 (to D.S.K.), R01 GM079265 (to D.R.K.), and R01 GM114201 (to D.V.). D.B.H. was supported by a fellowship from the Infectious Diseases Institute (OSU). A.J.H. was supported by MCB Training Grant T32 GM007183-39 and NSF GRFP DGE-1144082. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, D.S.K., D.B.H., E.K.; Methodology, D.B.H., E.K., A.J.H., D.R.K., D.V., M.E.Q., and D.S.K.; Investigation, E.K., D.B.H., B.W., A.J.H., and K.S.; Writing – Original Draft, D.B.H., E.K., and D.S.K.; Writing – Review & Editing, E.K., D.B.H., A.J.H., B.W., D.V., M.E.Q., and D.S.K.; Funding Acquisition, D.B.H., A.J.H., D.V., D.R.K., D.S.K.; Resources, M.E.Q., D.R.K.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Aktories K, Lang AE, Schwan C, Mannherz HG. Actin as target for modification by bacterial protein toxins. FEBS J. 2011;278:4526–4543. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kudryashova E, Quintyn R, Seveau S, Lu W, Wysocki VH, Kudryashov DS. Human defensins facilitate local unfolding of thermodynamically unstable regions of bacterial protein toxins. Immunity. 2014;41:709–721. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henkel JS, Baldwin MR, Barbieri JT. Toxins from Bacteria In Experientia Supplementum, 100. In: Luch A, editor. Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology. Birkhäuser; Basel: 2010. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemichez E, Aktories K. Hijacking of Rho GTPases during bacterial infection. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:2329–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blasi J, Chapman ER, Link E, Binz T, Yamasaki S, De Camilli P, Sudhof TC, Niemann H, Jahn R. Botulinum neurotoxin A selectively cleaves the synaptic protein SNAP-25. Nature. 1993;365:160–163. doi: 10.1038/365160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiavo G, Benfenati F, Poulain B, Rossetto O, Polverino de Laureto P, DasGupta BR, Montecucco C. Tetanus and botulinum-B neurotoxins block neurotransmitter release by proteolytic cleavage of synaptobrevin. Nature. 1992;359:832–835. doi: 10.1038/359832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudryashova E, Heisler DB, Kudryashov DS. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Actin Cross-Linking Toxins: Peeling Away the Layers. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2017;399:87–112. doi: 10.1007/82_2016_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satchell KJ. MARTX, multifunctional autoprocessing repeats-in-toxin toxins. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5079–5084. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00525-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pukatzki S, McAuley SB, Miyata ST. The type VI secretion system: translocation of effectors and effector-domains. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudryashov DS, Durer ZA, Ytterberg AJ, Sawaya MR, Pashkov I, Prochazkova K, Yeates TO, Loo RR, Loo JA, Satchell KJ, et al. Connecting actin monomers by iso-peptide bond is a toxicity mechanism of the Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18537–18542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudryashova E, Kalda C, Kudryashov DS. Glutamyl phosphate is an activated intermediate in actin crosslinking by actin crosslinking domain (ACD) toxin. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordero CL, Kudryashov DS, Reisler E, Satchell KJ. The Actin cross-linking domain of the Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin directly catalyzes the covalent cross-linking of actin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32366–32374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605275200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heisler DB, Kudryashova E, Grinevich DO, Suarez C, Winkelman JD, Birukov KG, Kotha SR, Parinandi NL, Vavylonis D, Kovar DR, et al. ACTIN-DIRECTED TOXIN. ACD toxin-produced actin oligomers poison formin-controlled actin polymerization. Science. 2015;349:535–539. doi: 10.1126/science.aab4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovar DR. Molecular details of formin-mediated actin assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dominguez R. The WH2 Domain and Actin Nucleation: Necessary but Insufficient. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41(6):478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fullner KJ, Mekalanos JJ. In vivo covalent cross-linking of cellular actin by the Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin. EMBO J. 2000;19:5315–5323. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millius A, Watanabe N, Weiner OD. Diffusion, capture and recycling of SCAR/WAVE and Arp2/3 complexes observed in cells by single-molecule imaging. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1165–1176. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padrick SB, Doolittle LK, Brautigam CA, King DS, Rosen MK. Arp2/3 complex is bound and activated by two WASP proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E472–479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100236108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suarez C, Carroll RT, Burke TA, Christensen JR, Bestul AJ, Sees JA, James ML, Sirotkin V, Kovar DR. Profilin regulates F-actin network homeostasis by favoring formin over Arp2/3 complex. Dev Cell. 2015;32:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higashida C, Miyoshi T, Fujita A, Oceguera-Yanez F, Monypenny J, Andou Y, Narumiya S, Watanabe N. Actin polymerization-driven molecular movement of mDia1 in living cells. Science. 2004;303:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1093923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bear JE, Gertler FB. Ena/VASP: towards resolving a pointed controversy at the barbed end. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1947–1953. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyoshi T, Tsuji T, Higashida C, Hertzog M, Fujita A, Narumiya S, Scita G, Watanabe N. Actin turnover-dependent fast dissociation of capping protein in the dendritic nucleation actin network: evidence of frequent filament severing. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:947–955. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winkelman JD, Bilancia CG, Peifer M, Kovar DR. Ena/VASP Enabled is a highly processive actin polymerase tailored to self-assemble parallel-bundled F-actin networks with Fascin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4121–4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322093111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch M, Le KHD, Bugyi B, Correia JJ, Renault L, Carlier MF. Analysis of the Function of Spire in Actin Assembly and Its Synergy with Formin and Profilin. Mol Cell. 2007;28:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CK, Sawaya MR, Phillips ML, Reisler E, Quinlan ME. Multiple Forms of Spire-Actin Complexes and their Functional Consequences. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10684–10692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.317792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinlan ME, Heuser JE, Kerkhoff E, Mullins RD. Drosophila Spire is an actin nucleation factor. Nature. 2005;433:382–388. doi: 10.1038/nature03241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaiswal R, Vizcarra CL, Quinlan ME, Goode BL. Single molecule imaging reveals that Spire and the formin Capu interact at barbed ends to antagonize capping protein and promote actin filament growth. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:P86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montaville P, Jegou A, Pernier J, Compper C, Guichard B, Mogessie B, Schuh M, Romet-Lemonne G, Carlier MF. Spire and Formin 2 Synergize and Antagonize in Regulating Actin Assembly in Meiosis by a Ping-Pong Mechanism. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiezlak M, Diring J, Abella J, Mouilleron S, Way M, McDonald NQ, Treisman R. G-actin regulates the shuttling and PP1 binding of the RPEL protein Phactr1 to control actomyosin assembly. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5860–5872. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfaumann V, Lang AE, Schwan C, Schmidt G, Aktories K. The actin and Rho-modifying toxins PTC3 and PTC5 of Photorhabdus luminescens: enzyme characterization and induction of MAL/SRF-dependent transcription. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:579–594. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alekhina O, Burstein E, Billadeau DD. Cellular functions of WASP family proteins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2017;130:2235–2241. doi: 10.1242/jcs.199570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duleh SN, Welch MD. WASH and the Arp2/3 complex regulate endosome shape and trafficking. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:193–206. doi: 10.1002/cm.20437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kast DJ, Zajac AL, Holzbaur EL, Ostap EM, Dominguez R. WHAMM Directs the Arp2/3 Complex to the ER for Autophagosome Biogenesis through an Actin Comet Tail Mechanism. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1791–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathiowetz AJ, Baple E, Russo AJ, Coulter AM, Carrano E, Brown JD, Jinks RN, Crosby AH, Campellone KG. An Amish founder mutation disrupts a PI(3)P-WHAMM-Arp2/3 complex-driven autophagosomal remodeling pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28:2492–2507. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-01-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campellone KG, Webb NJ, Znameroski EA, Welch MD. WHAMM is an Arp2/3 complex activator that binds microtubules and functions in ER to Golgi transport. Cell. 2008;134:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matas OB, Martinez-Menarguez JA, Egea G. Association of Cdc42/N-WASP/Arp2/3 signaling pathway with Golgi membranes. Traffic. 2004;5:838–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yi K, Unruh JR, Deng MQ, Slaughter BD, Rubinstein B, Li R. Dynamic maintenance of asymmetric meiotic spindle position through Arp2/3-complex-driven cytoplasmic streaming in mouse oocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1252–U1186. doi: 10.1038/ncb2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adighibe O, Turley H, Leek R, Harris A, Coutts AS, La Thangue N, Gatter K, Pezzella F. JMY protein, a regulator of P53 and cytoplasmic actin filaments, is expressed in normal and neoplastic tissues. Virchows Arch. 2014;465:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuchero JB, Coutts AS, Quinlan ME, La Thangue NB, Mullins RD. p53-cofactor JMY is a multifunctional actin nucleation factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:451–U198. doi: 10.1038/ncb1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schluter K, Waschbusch D, Anft M, Hugging D, Kind S, Hanisch J, Lakisic G, Gautreau A, Barnekow A, Stradal TEB. JMY is involved in anterograde vesicle trafficking from the trans-Golgi network. Eur J Cell Biol. 2014;93:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benesch S, Polo S, Lai FP, Anderson KI, Stradal TE, Wehland J, Rottner K. N-WASP deficiency impairs EGF internalization and actin assembly at clathrin-coated pits. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3103–3115. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen XJ, Squarr AJ, Stephan R, Chen BY, Higgins TE, Barry DJ, Martin MC, Rosen MK, Bogdan S, Way M. Ena/VASP Proteins Cooperate with the WAVE Complex to Regulate the Actin Cytoskeleton. Dev Cell. 2014;30:569–584. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]