Abstract

Medicinal berries are appreciated for their health benefits, in traditional ecological knowledge and nutrition science. Determining the cellular mechanisms underlying the effects of berry supplementation may contribute to our understanding of aging. Here, we report that lowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) treatment causes marked nuclear localization of the central aging-related transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO in aged Caenorhabditis elegans. Further, functional DAF-16 is required for the lifespan extension, improved mechanosensation, and posterior touch receptor neuron morphological changes induced by lowbush cranberry treatments. DAF-16 is not observed in nuceli nor required for lifespan extension in lifespan-extending Alaskan blueberry treatments and, while DAF-16 is not visibly induced into the nucleus in lifespan-extending Alaskan chaga treatments, it is required for chaga-induced lifespan extension. These findings underscore the importance of DAF-16 in the aging of whole organisms and touch receptor neurons and also, importantly, indicate that this critical pathway is not always activated upon consumption of functional foods that impact aging.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11357-018-0016-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aging, Mechanosensory neurons, DAF-16/FOXO, Caenorhabditis elegans, Cranberry

Introduction

In both humans and the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans, neurons are known to change shape and function with age (rather than dying), which in turn impacts the aging of the entire organism due to the central communication and integration functions of the nervous system. C. elegans are particularly well-suited for neuron aging studies because their transparency and genetic malleability allows for the engineering of strains with fluorescent tags on specific neurons. One class of C. elegans neurons known to change shape and function with age is the touch receptor (or mechanosensory) neurons, which sense soft touch. These neurons develop novel outgrowths from the soma, additional branching on the axon/dendrites, and abnormal soma shapes with age (Toth et al. 2012; Tank et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2011). The age-related development of these morphologies is regulated, in part, by two signaling pathways central to the regulation of lifespan and health span: the insulin/IGF and Jun kinase pathway (Toth et al. 2012; Tank et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2011; Scerbak et al. 2014). However, the cellular mechanisms by which these pathways (and likely others) regulate age-related changes in the morphology of touch receptor neurons have yet to be fully described.

Changes in intercellular communication and nutrient sensing at the organismal (e.g. olfaction) and cellular level (e.g., insulin signaling) are known to be associated with aging (reviewed in Lopez-Otin et al. 2013). In C. elegans, various mutations in components of the insulin signaling pathway, a key nutrient sensing pathway, consistently regulate lifespan, response to stress, and neuron aging (reviewed in Fontana et al. 2010; Broughton and Partridge 2009)). Two transcription factors central to the aging process and stress response are also responsive to insulin signaling: DAF-16/FOXO and HSF-1 (heat shock factor 1). In C. elegans, DAF-16 is well known to regulate the expression of a diverse set of genes to influence aging (reviewed in Mukhopadhyay et al. 2006; Hsu et al. 2003) and is thought to be involved in the aging of touch receptor neurons (Toth et al. 2012; Tank et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2011). Additionally, several epidemiological studies have indicated that genetic variation in the FOXO transcription factor is associated with human lifespan determination (Deelen et al. 2014; Beekman et al. 2013; Newman and Murabito 2013).

Environmental factors, including diet, are related to the molecular, cellular, and organismal changes that occur with age. For example, diets rich in fruits and vegetables are consistently correlated with increased lifespan, decreased incidence of age-related diseases, or both (reviewed in Fleming et al. 2013), perhaps because of their high polyphenolic content (Liu 2004). Cranberries are often touted as functional foods, with benefits ranging from improved cardiovascular health (reviewed in Basu et al. 2010) to the prevention of obesity (reviewed in Kowalska and Olejnik 2016). Even in C. elegans, American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) has wide ranging health benefits including lifespan extension (Guha et al. 2013), reduced fat accumulation (Sun et al. 2016), and reduced beta-amyloid peptide toxicity (Guo et al. 2015). Lowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea or lingonberry), native to boreal forest and tundra ecosystems, is traditionally valued in Alaska as a medicinal berry (Garabaldi 1999; Kari 1995). Wild, Alaskan lowbush cranberry contains higher levels of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds than commercially grown, temperate cranberry species (Grace et al. 2014; Dinstel et al. 2013).

We previously described the beneficial effects of commonly consumed and culturally relevant interior Alaskan plant and fungus species (bog blueberry, lowbush cranberry, and chaga fungus) on overall health, neuronal function, and touch receptor neuron morphology during aging (Scerbak et al. 2016). Here, we tested the hypothesis that central aging-related transcription factors, specifically DAF-16 and HSF-1, are involved in producing these observed effects in aging C. elegans neurons (e.g., increase in lifespan, alteration of aging neuron morphologies).

Materials and methods

C. elegans strains and maintenance

The following C. elegans strains used in this study were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) at the University of Minnesota: N2 (Bristol wildtype); TJ356 (DAF-16::GFP (zIs356 IV [daf-16p::daf-16a/b::GFP + rol-6])); OG497 (HSF-1::GFP (drSi13 II [hsf-1p::hsf-1::GFP::unc-54 3′UTR + Cbr-unc-119(+)]; unc-119(ed3) III)); GR1307 (daf-16(mgdf50)). ZB154 (zdIs5 [Pmec-4GFP; lin-15(+)]); and ZB4064 (zdIs5 [Pmec-4GFP; lin-15(+)]; uls57 [Punc-119SID-1, Punc-119YFP, Pmec-6mec-6]) were previously established as models of touch receptor neuron aging (Toth et al. 2012; Vayndorf et al. 2016). Both ZB154 and ZB4064 exhibit GFP-labeled touch receptor neurons (Toth et al. 2012), and ZB4064 overexpresses the SID-1 transmembrane channel in all neurons (Calixto et al. 2010), rendering neurons susceptible to RNA interference treatment.

We used standard methods to maintain and manipulate C. elegans populations (Brenner 1974). Stock populations were cultured at room temperature (about 22 °C) on Nematode Growth Media agar plates (1 L NGM: 2.5 g peptone, 17 g agar, 3 g NaCl, 975 mL double distilled water, 1 mL 5 mg/mL cholesterol, 1 mL 1 M CaCl2, 1 mL 1 M MgSO4, 25 mL 1 M KHPO4, and 0.5 mL 100 mg/mL streptomycin) seeded with live bacteria (E. coli strain OP50-1 cultured in Luria Broth) that were allowed to form a lawn for 2 days at room temperature and then stored at 4 °C until use. Unless otherwise indicated, all experiments were performed by culturing animals at 25 °C.

Berry and fungus extract preparation and treatment administration

The Alaskan berry and fungal extract preparations and treatment administration herein are the same as described previously (Scerbak et al. 2016). Therein, we described the biochemical makeup of the extracts used in this study. Briefly, extracts of wild Alaskan frozen, whole specimens of cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), and chaga (Inonotus obliquus) were prepared with 80% aqueous acetone and rotaevaporation (blueberry and cranberry), or boiling water and straining (chaga). To administer treatments, we cultured age-matched, day 1 adult C. elegans populations on NGM agar plates mixed with the appropriate concentration of extract and seeded with live OP50-1 E. coli at 25 °C. Control populations were cultured on standard NGM plates without extract. For experiments involving aged populations, animals were transferred with a platinum wire pick to fresh treatment plates to maintain synchrony and to avoid starvation and crowding. The experimenter was always blinded to the berry and/or fungus treatment dosage.

Lifespan analysis

For all lifespan experiments, we maintained age-matched C. elegans populations on prepared 35 × 10 mm extract plates as described in the section above at 25 °C. Each lifespan experiment consisted of two plates per condition (treatment or control) each beginning with 25 individuals per plate, to minimize the impact of population density on experimental results. Importantly, wildtype (N2) positive control experiments were conducted in parallel with each lifespan replicate to validate extract preparation and treatment administration. Animals were scored by hand for survival every other day until 6 days after egg lay, at which point plates were checked daily. We used the Kaplan-Meier log-rank test, with a pairwise over strata comparison, in the IBM SPSS Version 20 to measure treatment and genotype effects.

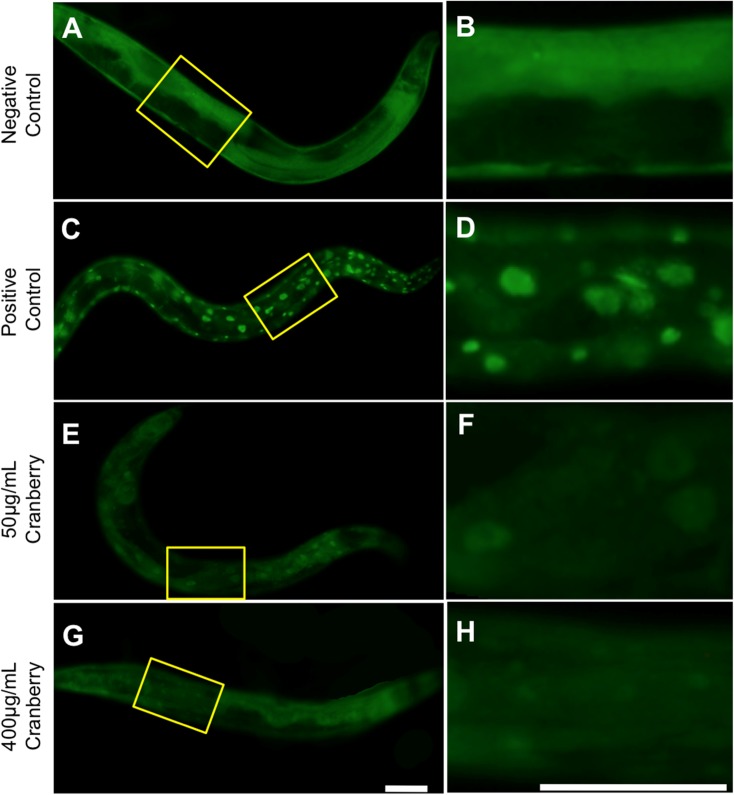

Transcription factor localization assays

To visualize the location of transcription factors known to be important in aging, we utilized two previously described C. elegans strains: TJ356 (DAF-16::GFP) (Henderson and Johnson 2001) and OG497 (HSF-1::GFP) (Morton and Lamitina 2013). Synchronous populations were allowed to develop on NGM plates for 72 h at 20 °C and cultured on appropriate treatment plates until imaging (on days 3 and 9 of adulthood). For animals expressing DAF-16::GFP, we imaged at × 10 magnification to visualize the entire animal. Positive controls were heat shocked for 30 min at 37 °C on agar plates and imaged immediately thereafter. Each DAF-16::GFP animal was classified into three groups based on the nuclear foci observed: diffuse fluorescence group, animals had no districting DAF-16::GFP foci present (Fig. 1a, b); nuclear group, animals had foci seen throughout the animal with very little diffuse fluorescence (Fig. 1c, d); and intermediate group, animals had at least three distinct DAF-16::GFP foci with mostly diffuse fluorescence (Fig. 1e, g) (Oh et al. 2005). For animals expressing HSF-1::GFP, only five individuals were prepared for imaging at once, the epithelial cell layer in the posterior third of each animal was imaged at × 40 and positive controls were heat shocked for 30 min at 35 °C after preparing for imaging. To detect treatment effects, we used an ordinal logistic statistics model.

Fig. 1.

Alaskan lowbush cranberry causes DAF-16/FOXO nuclear translocation late in life. Representative images of GFP-labeled DAF-16 (strain TJ356) day 9 adult (cultured at 20 °C) untreated negative (a–b) and positive (c–d) controls and treatment with lifespan-extending Alaskan lowbush cranberry treatments (50 and 400 μg/mL; e–h) are shown. Notice the presence of foci or punctae in the positive controls and both lowbush cranberry treatment groups (50 and 400 μg/mL). Yellow boxes on images to the left mark the magnified area in corresponding panels on the right. All images were collected at constant exposure and × 10 magnification. Positive control effects were induced by 30 min at 37 °C. Scale bars represent 60 μm for all images in each column

RNA interference treatment

To administer RNA interference (RNAi) treatment, we cultured age-synchronous populations of C. elegans on RNAi agar plates (2.5 g peptone, 17 g agar, 3 g NaCl, 1 mL 5 mg/mL cholesterol, 1 mL 1 M CaCl2, 1 mL 1 M MgSO4, 25 mL 1 M KHPO4, 1 mL 1 M isopropyl beta-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG], and 0.5 mL 50 mg/mL carbenicillin per 1 L) seeded with 4× concentrated L4440 (empty vector) HT115 E. coli protected from light at 25 °C. In this study, we performed RNAi experiments with strain ZB154 (whose neurons are not susceptible to RNAi knockdown via feeding) and all animals began RNAi treatment (and berry treatment, if required) after normal development—48 h after egg lay at 25 °C. All subsequent treatment and control plates consisted of RNAi plates mixed with varying concentrations of the appropriate extract as described above, seeded with 4× concentrated live HT115 bacteria from the Ahringer library. Bacterial dsRNA production was induced by growing the HT115 bacterial lawn at room temperature (22 °C) for 2 days, allowing us to target the desired C. elegans mRNA for degradation. The experimenter was always blinded to the RNAi and extract treatment regimens until statistical analysis. To verify the RNAi treatment conditions for each experiment, we performed control experiments measuring fluorescence knockdown following GFP RNAi treatment with strain ZB4064 (Supplemental Figure 1). RNAi clone identity was verified by sequencing (Macrogen Corp.; primer M13F) after plasmid extraction with the QIA Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen).

Touch receptor neuron morphology and touch response analysis

On day 11 of adulthood (10 days after beginning RNAi/extract treatment), ZB154 individuals were randomly selected from a synchronous population and tested for motility, touch sensitivity, and touch receptor neuron aberrations. We assigned individuals to three classes based on their motility: class A individuals moved normally and spontaneously; class B individuals moved in markedly non-sinusoidal manner and, often, non-spontaneously; and class C individuals were alive but unable to translocate (Herndon et al. 2002). We measured soft touch sensitivity by counting the number of positive responses an individual had to five alternating touches at each the anterior and posterior ends (ten total touches) (Calixto et al. 2010). Finally, to visualize the fluorescently labeled touch receptor neurons, we mounted individuals to a coverslip with 36% Pluronic (BASF) solution, and imaged the neurons with an Olympus FSX100 inverted fluorescent microscope at × 20 magnification. We quantified the occurrence of abnormal morphologies in the anterior and posterior lateral touch receptor neurons (ALM and PLM) of each individual and collected reference images. The neuron morphologies observed included those previously described (Toth et al. 2012; Tank et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2011; Scerbak et al. 2014), such as various lengths of outgrowths from the soma (e.g., short or extended), branches from the process, abnormally shaped soma, punctae on the process, and abnormally located soma. Additional morphologies were also observed and included branches from the process that connected back to the process (i.e., loops) and deformed process sections (i.e., tangles). We performed Poisson log linear (for count data, e.g., touch response) or logistic regression (for bimodal data, e.g., presence of abnormal cell soma) statistical models to test for treatment and age effects on touch sensitivity and neuron morphologies using SPSS (version 20) statistical software. Pairwise comparisons with p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. We repeated this experiment in at least three independent trials for each combination of RNAi and extract treatment, each with a parallel empty vector L4440 no treatment control.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Alaskan lowbush cranberry causes nuclear translocation of DAF-16/FOXO late in life

The well-studied DAF-16/FOXO and HSF-1 transcription factors are involved in longevity and stress response (reviewed in (Hsu et al. 2003). We tested the location (cytosol or nucleus) of these central transcription factors in Alaskan berry and fungus treatments that we previously observed to extend C. elegans lifespan and health span and to impact age-related changes in touch receptor neuron morphology and function (Scerbak et al. 2016). The polyphenolic content (total phenolic, flavonoid, and anthocyanin content) of these extracts was previously described (Scerbak et al. 2016) and the abundance of these compounds in our extracts was similar to the levels described by other research groups (Grace et al. 2014). C. elegans strains with GFP-tagged DAF-16 (strain TJ356) (Henderson and Johnson 2001) or HSF-1 (strain OG497) (Morton and Lamitina 2013) are available to visualize the nuclear translocation of these transcription factors in response to stress, which has previously been shown to coincide increased gene expression of target genes associated with these transcription factors and transcription factor binding to the DNA (Henderson and Johnson 2001; Morton and Lamitina 2013). In the DAF-16::GFP animals, diffuse fluorescence indicates that the transcription factor has not translocated to the nuclei (Fig. 1a, b). DAF-16 can be observed in the nuclei of cells as distinct foci in response to stressors, such as heat shock (Fig. 1c, d).

After 48 h of treatment with lifespan-extending Alaskan berry and fungus treatments (day 3 of adulthood), we did not detect translocation of DAF-16 into nuclear foci with any treatment (Supplemental Figure 1). However, at day 9 of adulthood (after 8 days of treatment), we observed formation of DAF-16 nuclear foci in both lifespan-extending lowbush cranberry treatments (Fig. 1e–h; Table 1; Supplemental Figure 3). Blueberry and chaga treatments did not lead to detectable DAF-16 nuclear foci early (Supplemental Figure 1) or late in life (day 9 adulthood; Supplemental Figure 2).

Table 1.

Alaskan lowbush cranberry treatments lead to DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci formation later in life

| Treatment | Percent (%) of animals tested | Statistical group | Observed number of foci per animal (mean ± SE; max value; p value) | Total sample size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosolic | Intermediate | Nuclear | ||||

| 0 positive control (heat shock) | 0 | 0 | 100 | a | All | 20 |

| 0 negative control | 72.7 | 27.3 | 0 | b | 1.06 ± 0.245 | 33 |

| 50 μg/ml lowbush cranberry | 38.7 | 61.3 | 0 | c | 4.06 ± 0.829; p = 0.001 | 31 |

| 400 μg/ml lowbush cranberry | 19.3 | 80.6 | 0 | c | 5.00 ± 0.6574; p < 0.001 | 31 |

Animals were classified as cytosolic, intermediate, or nuclear based on the presence of DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci at day 9 of adulthood (cultured at 20 °C) following treatment. Animals with cytosolic DAF-16 had diffused GFP expression throughout the animal (example in Fig. 1a), nuclear DAF-16 foci seen throughout the animal with very little diffuse fluorescence (example in Fig. 1c), and intermediate DAF-16 had at least three distinct DAF-16::GFP foci with mostly diffuse fluorescence (examples in Fig. 1e, g). Treatments were grouped into statistically homogenous subsets as listed in the “Statistical group” column (p < 0.05, ordinal logistic model). The average number of foci observed per animal is also shown, with the p value representing significance from untreated control (one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc; box and whisker plot of data shown in Supplemental Figure 3). All animals exposed to heat shock had a robust response DAF-16 translocation, thus we estimate that all of the cells had DAF-16 foci (no observable diffuse fluorescence). Data and sample size represent all individuals examined from three independent trials, each with a significant effect

In the HSF-1::GFP strain, HSF-1 is observed in nuclei under normal conditions and upon exposure to stress, forms distinct granules within nuclei, representing HSF-1 binding to DNA (Supplemental Figure 1) (Morton and Lamitina 2013). We were unable to detect formation of HSF-1::GFP granules within nuclei following 48 h of any lifespan-extending Alaskan berry and fungus treatment (Supplemental Figure 1). Interestingly, HSF-1::GFP animals had granules in all groups (including untreated control) late in adulthood (day 9; Supplemental Figure 4), making it unfeasible for this method to determine whether HSF-1 is located in cellular nuclei later in life due to Alaskan berry and fungus treatments.

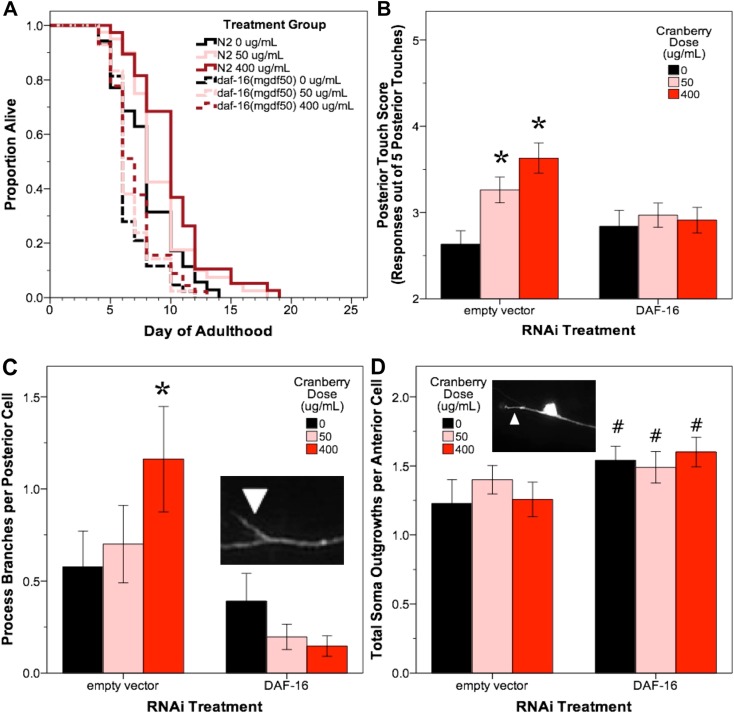

Alaskan lowbush cranberry modulates DAF-16 to extend lifespan

To examine whether the DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci observed after lowbush cranberry treatment reflect a requirement for functional DAF-16 in lowbush cranberry-mediated lifespan extension, we treated C. elegans DAF-16 mutant populations (strain GR1307; daf-16(mgdf50); (Ogg et al. 1997) with lowbush cranberry doses that extended wildtype lifespan (50 and 400 μg/mL; (Scerbak et al. 2016). These DAF-16 mutants did not respond with increased lifespan to lowbush cranberry treatment, which suggests that the requirement of a functional DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor is needed for lifespan extension via lowbush cranberry treatment (Fig. 2a; Table 2; Supplemental Figure 5).

Fig. 2.

Alaskan lowbush cranberry treatment requires DAF-16 for lifespan extension and posterior neuron branching events late in life. Lowbush cranberry treatments that extend wildtype C. elegans lifespan (50 and 400 μg/mL) do not extend the lifespan of DAF-16 mutant animals (daf-16(mgdf50)). Representative Kaplan-Meier curve is shown, with age in days of adulthood cultured at 25 °C (corresponding data shown in trial 1 columns of Table 2) and results were replicated in three independent trials (a). In ZB154, animals (GFP-labeled mechanosensory neurons, not susceptible to neuronal RNAi knock-down) on day 11 of adulthood cultured at 25 °C, DAF-16 RNAi treatment blocks lowbush cranberry treatment-mediated improvement in posterior touch response (50 and 400 μg/mL; a, b) and increased posterior process branching (400 μg/mL; c) and impacts ZB154 anterior cell soma outgrowth development in treatment groups somewhat significantly (50 and 400 μg/mL; d). Asterisks denote significant difference (p < 0.05; Poisson log linear model) from untreated control in each RNAi treatment group. Hashtags denote slight significance (0.09 < p < 0.06; Poisson log linear model) compared to treatment matched empty vector control. Insets in C and D are representative images of touch receptor neurons with the appropriate neuron morphology marker (anterior of each individual oriented to the left). Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean. Nworms = 17–31, Nanterior cells = 22–40 cells, and Nposterior cells = 26–51 per bar

Table 2.

The effect of Alaskan berry and fungus treatments on daf-16(mgdf50) mutant lifespan

| Extract treatment | Genotype | Dose (μg/mL) | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifespan (mean days of adulthood ± S.E.M., N) | Treatment effect (percent (%) of untreated control, p value) | Lifespan (mean days of adulthood ± S.E.M., N) | Treatment effect (percent (%) of untreated control, p value) | Lifespan (mean days of adulthood ± S.E.M., N) | Treatment effect (percent (%) of untreated control, p value) | |||

| Blueberry | Wildtype (N2) | 0 | 10.87 ± 0.50, 50 | 9.23 ± 0.33, 45 | 9.35 ± 0.38, 50 | |||

| 60 | 12.92 ± 0.42, 50 | 119, p = 0.004 | 10.51 ± 0.38, 50 | 119, p = 0.010 | 11.38 ± 0.66, 50 | 121, p = 0.009 | ||

| 200 | 12.11 ± 0.37, 45 | 111, p = 0.023 | 11.00 ± 0.50, 50 | 111, p = 0.003 | 12.09 ± 0.62, 50 | 129, p < 0.001 | ||

| daf-16 (mgdf50) | 0 | 9.85 ± 0.50, 50 | 8.09 ± 0.42, 49 | 8.22 ± 0.33, 50 | ||||

| 60 | 13.40 ± 0.49, 48 | 136, p < 0.001 | 9.85 ± 0.71, 50 | 121, p = 0.021 | 9.21 ± 0.58, 50 | 112, p = 0.157 | ||

| 200 | 15.80 ± 0.83, 41 | 160, p < 0.001 | 9.99 ± 0.66, 50 | 123, p = 0.016 | 9.89 ± 0.59, 50 | 120, p = 0.012 | ||

| Lowbush cranberry | Wildtype (N2) | 0 | 8.48 ± 0.41, 50 | 10.94 ± 0.50, 50 | 9.35 ± 0.38, 50 | |||

| 50 | 9.43 ± 0.47, 50 | 112, p = 0.115 | 11.53 ± 0.87, 50 | 105, p = 0.024 | 10.62 ± 0.45, 50 | 113, p = 0.033 | ||

| 400 | 10.46 ± 0.49, 50 | 123, p = 0.003 | 12.41 ± 0.57, 50 | 113, p = 0.054 | 11.59 ± 0.63, 50 | 123, p = 0.003 | ||

| daf-16 (mgdf50) | 0 | 7.17 ± 0.33, 50 | 8.15 ± 0.39, 48 | 8.22 ± 0.33, 50 | ||||

| 50 | 6.97 ± 0.31, 50 | 97, p = 0.664 | 8.84 ± 0.36, 49 | 108, p = 0.394 | 8.27 ± 0.29, 50 | 100, p = 1.000 | ||

| 400 | 7.65 ± 0.44, 50 | 106, p = 0.119 | 8.55 ± 0.38, 50 | 105, p = 0.994 | 8.58 ± 0.41, 50 | 104, p = 0.393 | ||

| Chaga | Wildtype (N2) | 0 | 9.50 ± 0.76, 50 | 10.02 ± 0.56, 40 | 9.95 ± 0.69, 50 | |||

| 50 | 11.32 ± 0.53, 48 | 119, p = 0.086 | 12.29 ± 0.60, 41 | 123, p = 0.016 | 12.65 ± 0.51, 50 | 127, p = 0.011 | ||

| 200 | 12.92 ± 0.70, 48 | 136, p = 0.038 | 12.65 ± 0.86, 42 | 126, p = 0.012 | 12.90 ± 0.77, 50 | 129, p = 0.015 | ||

| daf-16 (mgdf50) | 0 | 8.36 ± 0.68, 50 | 9.67 ± 0.42, 45 | 8.58 ± 0.50, 50 | ||||

| 50 | 7.43 ± 0.39, 50 | 89, p = 0.131 | 9.10 ± 0.44, 46 | 94, p = 0.248 | 9.21 ± 0.53, 45 | 107, p = 0.563 | ||

| 200 | 8.27 ± 0.48, 50 | 99, p = 0.674 | 9.32 ± 0.37, 48 | 96, p = 0.204 | 8.82 ± 0.64, 38 | 102, p = 0.391 | ||

Experimental results for Alaskan blueberry-, lowbush cranberry-, and chaga-treated mutant DAF-16 C. elegans (daf-16(mgdf50)) are shown. Lifespan data (mean lifespan in days of adulthood, S.E.M., number of animals in each group, percent of untreated genotype control) for two trials for each treatment, each performed with two 35-mm plates beginning with N = 25 adults and cultured at 25 °C, are shown. Significance from appropriate control (p value) calculated using the Kaplan-Meier log-rank test and represents the comparison to untreated control for that genotype. For all trials, the wildtype (N2) control and DAF-16 (daf-16(mgdf50)) mutant lifespan experiments for each treatment regimen were conducted in parallel at 25 °C. (Note: trial 3 blueberry and cranberry treatment groups were all conducted in parallel, thus the untreated controls for both treatment groups are the same populations/lifespan data)

Another research team observed that blueberry polyphenol-mediated lifespan extension does not require DAF-16 (Wilson et al. 2006). To test whether this is also the case with Alaskan blueberry treatments and to verify our DAF-16::GFP nuclear translocation screening results, we measured the lifespan of DAF-16 mutants (strain GR1307; daf-16(mgdf50)) with lifespan-extending blueberry treatments (60 and 200 μg/mL). DAF-16 mutants maintained blueberry-mediated lifespan extension similar to that of wildtype (p < 0.05; Kaplan-Meier log-rank test; Table 2), indicating that DAF-16 is most likely not required for lifespan extension from blueberry treatment. Interestingly, chaga-mediated lifespan extension did require DAF-16 (Table 2; Supplemental Figure 5), but we were unable to detect DAF-16 nuclear translocation in live animals early or late in life (Supplemental Figures 1–2).

Alaskan lowbush cranberry modulates DAF-16 to influence touch receptor neuron aging

In young adults, the touch receptor neurons comprise of two posterior lateral mechanoreceptors (PLM) and two anterior lateral mechanoreceptors (ALM). These four neurons consist of a spherical cell soma with axon projections (also called processes) towards the head of the animal. With age, these neurons exhibit decreased function (i.e., decreased responsiveness to touch) and altered morphology; ALM neurons develop additional outgrowths from the soma (see inset in Fig. 2d) and abnormal (non-spherical) cell soma and PLM neurons develop addition growths on the axon (i.e., branches; see inset in Fig. 2c; (Toth et al. 2012; Tank et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2011)).

We previously reported that lifespan-extending lowbush cranberry treatment increased the incidence of axon branching in posterior touch receptor neurons and improved touch response late in life (Scerbak et al. 2016). Thus, we evaluated the involvement of DAF-16 in these lowbush cranberry-mediated aging effects of the touch receptor neurons. To do this, we compared the effects of lowbush cranberry, daf-16(RNAi), and lowbush cranberry-daf-16(RNAi) combination treatments on touch receptor neuron morphology and touch response in old (day 11) ZB154 animals (six GFP-labeled touch receptor neurons). These experiments specifically tested the involvement of non-neuronal DAF-16 in the observed lowbush cranberry-induced increase in posterior cell branching events (as wildtype C. elegans neurons, lacking the SID-1 channel, are not susceptible to RNAi; (Calixto et al. 2010).

We observed that daf-16(RNAi) completely blocked the increase in posterior touch response with empty vector lowbush cranberry treatments (p > 0.8; Poisson log linear model; Fig. 2b). daf-16(RNAi) resulted in the same occurrence of posterior neuron process branching events as untreated empty vector control animals (p > 0.1 Poisson log linear model; Fig. 2c). Also, daf-16(RNAi)-untreated and lowbush cranberry-treated groups were not significantly different from untreated empty vector control in anterior touch response and most anterior neuron aberrations (p > 0.1, Poisson log linear model). DAF-16 treatment did somewhat increase the number of anterior soma outgrowths observed at day 11 in all lowbush cranberry treatment groups; however, the change did not reach significance (111% of empty vector controls; 0.09 > p > 0.06 Poisson log linear model), suggesting that DAF-16 may be involved in the development of these aberrations through a mechanism not impacted by lowbush cranberry treatment (Fig. 2d).

Discussion

The cellular and molecular mechanisms behind the health benefits of nutritional interventions can be complex and challenging to elucidate. Here, we described a requirement for DAF-16/FOXO in Alaskan lowbush cranberry-mediated lifespan extension and altered touch receptor neuron aging (i.e., the development of posterior process branching). After observing DAF-16 nuclear foci in aged (day 9 adult) lowbush cranberry-treated populations (Fig. 1), we examined lifespan and touch receptor neuron aging following DAF-16 knockdown with RNA interference (RNAi). We demonstrated that DAF-16 is required both for the lifespan extension and the increased posterior touch receptor neuron (PLM) branching caused by lowbush cranberry treatments (Fig. 2).

The neuroprotective role of DAF-16 in healthy, untreated touch receptor neuron aging has been explored (Toth et al. 2012; Tank et al. 2011; Scerbak et al. 2014). Toth et al. (2012) demonstrated that increased DAF-16 activity due to decreased insulin signaling (daf-2(e1370) mutant background) resulted in increased PLM process branching in otherwise untreated animals by late in life (day 10 of adulthood). Conversely, Tank et al. (2011) observed decreased posterior cell branching in the same genetic background. However, removal of DAF-16 via genetic mutation and RNAi does not drastically disrupt aging touch receptor neuron morphologies, but does decrease touch response when compared to wildtype aging (Toth et al. 2012; Tank et al. 2011; Scerbak et al. 2014), which is consistent with our results (Fig. 2; black bars). While the involvement of DAF-16 in lifespan extension is well explored (albeit complex), our correlation of specific touch receptor neuron morphology (posterior neuron process branching) with berry-induced DAF-16 nuclear translocation is novel. What remains to be determined is whether PLM process branching is a stimulatory response that actively promotes healthy aging or whether this phenotype occurs as a consequence of good health and aging.

The number and distribution of DAF-16::GFP foci observed upon cranberry treatment (DAF-16 is not in nucleus of all cells and most nuclear foci are concentrated at the mid-region of animal; Fig. 1) and the results of the systemic (non-neuronal) DAF-16 RNAi experiments (Fig. 2) suggest that, at least in part, a non-neuron-specific pathway induces posterior neuron process branching. DAF-16, orthologous to human FOXO, is well known to operate in multiple tissues downstream of various cellular signaling pathways (e.g., insulin signaling) regulating the expression of genes that promote longevity, proteostasis, and stress response (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2006). Lowbush cranberry treatment facilitates DAF-16 translocation into the nucleus late in life (day 9; Fig. 1), promoting mechanosensory neuron phenotypes associated with longevity (i.e., day 11 improved mechanosensation, Fig. 2b; increased posterior neuron process branching, Fig. 2c). When systemic (non-neuronal) DAF-16 translation is decreased via RNAi feeding, these longevity-associated neuronal phenotypes are blocked (Fig. 2). In addition to supporting the vast body of evidence that DAF-16 signaling promotes longevity in C. elegans, these findings highlight the importance of cell-cell communication in the aging organism. Non-neuronal DAF-16 signaling (or lack of it) in response to an organism’s environment (e.g., cranberry supplementation), impacts neuronal phenotypes associated with aging.

The involvement of DAF-16 in the health benefits of Alaskan lowbush cranberry treatment is consistent with other work demonstrating that wildtype C. elegans lifespan extension with North American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) treatment requires DAF-16 (Guha et al. 2013). Others have shown that beneficial cranberry treatment effects required HSF-1 and not DAF-16 in a C. elegans model of Alzheimer’s disease (Guo et al. 2015), demonstrating the diverse functions of DAF-16 in different health and stress scenarios and a robust response of DAF-16 signaling to shared phytochemical(s) present in two different species of cranberry. The chemical differences of the blueberry, lowbush cranberry, and chaga extracts in the current study are quite striking, with cranberry containing by far the most total flavonoid content and chaga containing the least amounts of all compounds measured (total phenol, total flavonoid, and anthocyanin content; (Scerbak et al. 2016). While all three of these extracts increase lifespan and alter neuron aging in C. elegans, it is not surprising that they seem to do so through different mechanisms.

We did not observe DAF-16 nuclear foci formation in blueberry or chaga treatments (Supplemental Figures 1–2) yet DAF-16 was differentially required for lifespan extension in the two treatments (Table 2; Supplemental Figure 5). That we did not detect a requirement for DAF-16 for blueberry-mediated lifespan extension is not surprising (Table 2); others have shown that DAF-16 is not required in lifespan extension in treatment with other species of blueberry (V. angustifolium), and blueberry-derived polyphenols (Wilson et al. 2006). However, lifespan extension from chaga treatment did require functional DAF-16 (Table 2). That we were unable to detect DAF-16::GFP nuclear localization in chaga treatments may be in part due to the difference in culturing temperature between the lifespan experiments (25 °C) and DAF-16::GFP experiments (20 °C). The thermal effects on C. elegans lifespan and DAF-16 signaling are well known and DAF-16 signaling in the specific strain used in this study (TJ356) is responsive to specific temperatures (Henderson and Johnson 2001). The same genetic intervention involving DAF-16 signaling (e.g., daf-2 RNAi) can exhibit different DAF-16::GFP nuclear localization at different temperatures (Leiser et al. 2011), emphasizing the importance of temperature on this transcription factor and on experimental design. However, we have not found published examples of an increase in DAF-16::GFP localization from very low incidence (< 10% of animals) to notable translocation (> 40%) due to a change in culturing temperature within treatment groups. There are several examples of interventions impacting lifespan relative to untreated, N2 control populations differently under different culturing temperatures (for example, (Leiser et al. 2011; Horikawa et al. 2015; Miller et al. 2017)). Differences in culturing temperature most certainly impact aging in more ways than simply altering metabolic rates (i.e., not all interventions impact lifespan in the same direction at all culturing temperatures), and, relevant to the current study, this may play a central role in the longevity- and health-promoting phenotypes caused by chaga treatment. Exploring the interconnected role of temperature and extract treatments on cellular signaling cascades is an area of growth for future research.

Interestingly, in our previous work, both lowbush cranberry and chaga treatments were shown to induce posterior touch receptor neuron branching events late in life (Scerbak et al. 2016). However, in this same study, chaga treatment caused an additional phenotype among posterior neurons not observed with lowbush cranberry treatments—process loops. The mechanisms driving posterior touch receptor neuron branching events versus posterior loop events are likely distinct. We believe that the lack of detection of DAF-16 involvement in chaga treatments may also be due to the following: (1) chaga treatments specifically activate neuronal DAF-16, causing branching while escaping detection in the aging DAF-16::GFP model; (2) DAF-16 is activated at a time point other than the two we tested (day 3 and day 9); and/or (3) an additional, as of yet undescribed pathway exists to regulate PLM process branching (and loops). These findings support the growing evidence that C. elegans touch receptor neuronal aging is regulated via multiple mechanisms, including well-studied (e.g., insulin/IGF signaling) and novel pathways.

Both the presence of nutrients and the ability of an organism to sense and biologically respond to nutrients, such as medicinal berries, have profound implications for health and aging. The well-conserved insulin signaling pathway (of which DAF-16/FOXO is a critical component) epitomizes this statement; this pathway coordinates organismal response to nutrients and is well-known to be involved in the aging of a wide range of organisms from yeast to humans. Given the known genetic variation in human FOXO (Deelen et al. 2014; Beekman et al. 2013; Newman and Murabito 2013), the potential for individual variation in the response (e.g., inactivate/activate, speed and duration of response) of this transcription factor in response to nutrients and/or bioactive compounds should be investigated.

Electronic supplementary material

DAF-16 and HSF-1 nuclear translocation are not induced after treatment with Alaskan berry or fungus treatment in day 3 adults. Representative images of age-matched, GFP-labeled DAF-16 (strain TJ356) or HSF-1 (strain OG497) day 3 adult (cultured at 20 °C) untreated positive and negative controls and 48-h treatment with lifespan-extending Alaskan berry and fungus treatments are shown. Notice the striking appearance of the positive controls for each strain when compared with other treatment groups. DAF-16::GFP positive control foci represent the translocation of DAF-16 from the cytosol to the nucleus while HSF-1::GFP positive control foci (within the larger nucleus) represent nuclear HSF-1 binding to DNA. DAF-16::GFP images (left panels) were collected at × 10 and HSF-1::GFP images (right panels) were collected at × 40 magnification. Positive control effects were induced by 30 min at 37 °C (DAF-16) or 35 °C (HSF-1). Scale bars represent 60 μm for the images in each column. (DOCX 607 kb)

DAF-16 translocates into the nucleus in day 9 adults treated with lowbush cranberry, but not blueberry or chaga treatments. Two representative images of each age-matched, GFP-labeled DAF-16 (strain TJ356) day 9 adult untreated positive and negative controls and 9 days of treatment with lifespan-extending treatments are shown. All animals were treated with lifespan-extending treatments of Alaskan botanicals (as listed in figure) from day 1 of adulthood until imaging at day 9 of adulthood. All individual animals shown are different from those shown in Fig. 1. Positive control effects were induced by 30 min at 37 °C. Alaskan berry and fungus treatments are shown. Yellow boxes mark the location of nuclear foci in treatment groups. All images were collected at × 10 magnification and the scale bar represents 60 μm for all of the images. (DOCX 471 kb)

Alaskan lowbush cranberry treatments lead to DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci formation later in life (day 9 adults). Box and whisker plot represents the number of DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci observed per lowbush cranberry treatment (50 and 400 μg/mL) in day 9 adults (quantified from images as in Supplemental Figure 2). Boxes represent the upper and lower quartile of animals per group, while the line in each box represents the median number of foci observed per treatment. There is one outlier in each of the cranberry treatment groups, represented by the unfilled circles. The untreated positive control treatment (heat shock) is omitted from this plot because there was no diffuse fluorescence observed in any head shock animals, indicating that most (if not all) cells in these individuals had DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci. (DOCX 51 kb)

HSF-1::GFP granule formation occurs in negative controls in old age. Representative images of age-matched, GFP-labeled HSF-1 (strain OG497) day 9 adult untreated positive and negative controls are shown. Notice the similar occurrence of granule formation (which represents HSF-1 binding to DNA) in both untreated negative control and heat shocked positive control animals, especially when compared to the positive control effect observed in young adults (shown in Supplemental Figure 1). All images were collected at × 40 magnification. Positive control effects were induced by 30 min at 35 °C. Scale bar represents 60 μm for all images. (DOCX 526 kb)

The effect of Alaskan berry and fungus treatments on daf-16(mgdf50) mutant lifespan. Survival curves showing the effect of Alaskan berry and fungus treatments on daf-16(mgdf50) mutant lifespan. Experimental results for Alaskan blueberry- (A–C), lowbush cranberry- (D–F), and chaga-treated (G–I) wildtype and DAF-16 mutant (daf-16(mgdf50)) C. elegans lifespan experiment trials are shown. All curves align with the survival data shown in Table 2. Approximately 50 animals represented per treatment (line) in each graph (exact sample sizes listed in Table 2). Note that D is the same survival curve shown in Fig. 2A. (DOCX 466 kb)

Acknowledgements

Portions of this work were first published in the CS’s Ph.D. thesis. The authors would like to thank the Driscoll lab for the ZB154 strain and members of the Taylor/Harris laboratory and Dr. Marton Toth for their support. Some C. elegans strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Author contributions

CS conducted experiments, performed data analyses, and lead manuscript writing efforts. EV advised and assisted in experimental design and participated in in-depth discussions about methods, data analysis, and results. AH assisted in data collection and analysis and prepared figures. CM advised and assisted with Alaskan berry and fungus extractions. BT participated in in-depth methods and results discussions, provided detailed writing and editing assistance, and provided funding for the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Work reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (1) under an Institutional Development Award (IdeA; grant number P20GM103395) and (2) under three linked awards numbered RL5GM118990, TL4 GM 118992, and 1UL1GM118991.

Compliance with ethical standards

Disclaimer

The work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11357-018-0016-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Basu A, Rhone M, Lyons TJ. Berries: emerging impact on cardiovascular health. Nutr Rev. 2010;68(3):168–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman M, Blanché H, Perola M, Hervonen A, Bezrukov V, Sikora E, Flachsbart F, Christiansen L, de Craen AJM, Kirkwood TBL, Rea IM, Poulain M, Robine JM, Valensin S, Stazi MA, Passarino G, Deiana L, Gonos ES, Paternoster L, Sørensen TIA, Tan Q, Helmer Q, van den Akker EB, Deelen J, Martella F, Cordell HJ, Ayers KL, Vaupel JW, Törnwall O, Johnson TE, Schreiber S, Lathrop M, Skytthe A, Westendorp RGJ, Christensen K, Gampe J, Nebel A, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Slagboom PE, Franceschi C, the GEHA consortium Genome-wide linkage analysis for human longevity: genetics of healthy aging study. Aging Cell. 2013;12:184–193. doi: 10.1111/acel.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton S, Partridge L. Insulin/IGF-like signaling, the central nervous system and aging. Biochem J. 2009;418:1–12. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calixto A, Chelur D, Topalidou I, Chen X, Chalfie M. Enhanced neuronal RNAi in C. elegans using SID-1. Nat Methods. 2010;7:554–559. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deelen J, Beekman M, Uh HW, Broer L, Ayers KL, Tan Q, Kamatani Y, Bennet AM, Tamm R, Trompet S, Guðbjartsson DF, Flachsbart F, Rose G, Viktorin A, Fischer K, Nygaard M, Cordell HJ, Crocco P, van den Akker EB, Böhringer S, Helmer Q, Nelson CP, Saunders GI, Alver M, Andersen-Ranberg K, Breen ME, van der Breggen R, Caliebe A, Capri M, Cevenini E, Collerton JC, Dato S, Davies K, Ford I, Gampe J, Garagnani P, de Geus EJC, Harrow J, van Heemst D, Heijmans BT, Heinsen FA, Hottenga JJ, Hofman A, Jeune B, Jonsson PV, Lathrop M, Lechner D, Martin-Ruiz C, Mcnerlan SE, Mihailov E, Montesanto A, Mooijaart SP, Murphy A, Nohr EA, Paternoster L, Postmus I, Rivadeneira F, Ross OA, Salvioli S, Sattar N, Schreiber S, Stefánsson H, Stott DJ, Tiemeier H, Uitterlinden AG, Westendorp RGJ, Willemsen G, Samani NJ, Galan P, Sørensen TIA, Boomsma DI, Jukema JW, Rea IM, Passarino G, de Craen AJM, Christensen K, Nebel A, Stefánsson K, Metspalu A, Magnusson P, Blanché H, Christiansen L, Kirkwood TBL, van Duijn CM, Franceschi C, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Slagboom PE. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of human longevity identifies a novel locus conferring survival beyond 90 years of age. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4420–4432. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinstel RR, Cascio J, Koukel S. The antioxidant level of Alaska’s wild berries: high, higher, highest. Nutrition. 2013;1:1–7. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JA, Holligan S, Kris-Etherton PM. Dietary patterns that decrease cardiovascular disease and increase longevity. J Clin Exp Cardiol. 2013;S6:006. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy lifespan—from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328(5976):321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garabaldi A. Medicinal flora of the Alaska Natives. Anchorage: Environment and Natural Resources Institute, Alaska Natural Heritage Program; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grace MH, Esposito D, Dunlap KL, Lila MA. Comparative analysis of phenolic content and profile, antioxidant capacity, and anti-inflammatory biocactivity in wild Alaskan and commerical Vaccinium berries. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(8):4007–4017. doi: 10.1021/jf403810y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha S, Cao M, Kane R, Savino A, Zou S, Dong Y. The longevity effect of cranberry extract in Caenorhabditis elegans is modulated by daf-16 and osr-1. Age. 2013;35(5):1559–1574. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9459-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Cao M, Zou S, Ye B, Dong Y (2015) Cranberry extract standardized for proanthocyanidins alleviates beta-amyloid peptide toxicity by imroving proteostasis through HSF-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci :1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Henderson S, Johnson T. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11(24):1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon LA, Schmeissner PJ, Dudaronek JM, Brown PA, Listner KM, Sakano Y, Paupard MC, Hall DH, Driscoll M. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature. 2002;419(6909):808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa M, Sural S, Hsu A-L, Antebi A. Co-chaperone p23 regulates C. elegans lifespan in response to temperature. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(4):e1005023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu AL, Murphy C, Kenyon C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science. 2003;300:1142–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.1083701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kari PR. Tanaina plantlore, Dena’ina k’et’una. 4. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center, Alaska Nat Hist; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska K, Olejnik A. Beneficial effects of cranberry in the prevention of obesity and related complications: metabolic syndrome and diabetes—a review. J Funct Foods. 2016;20:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leiser SF, Begun A, Kaeberlein M. HIF-1 modulates longevity and healthspan in a temperature-dependent manner. Aging Cell. 2011;10(2):318–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RH. Potential synergy of phytochemicals in cancer prevention: mechanisms of action. J Nutr. 2004;134:3479–3485. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3479S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller H, Fletcher M, Pimitivo M, Leonard A, Sutphin GL, Rintala N, Kaeberlein M, Leiser SF. Genetic interaction with temperature is an important determinant of nematode longevity. Aging Cell. 2017;16(6):1425–1429. doi: 10.1111/acel.12658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton E, Lamitina T. Caenorhabditis elegans HSF-1 is an essential nuclear protein that forms stress granule-like structures following heat shock. Aging Cell. 2013;12:112–120. doi: 10.1111/acel.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A, Oh SW, Tissenbaum H. Worming pathways to and from DAF-16/FOXO. Exp Geron. 2006;41(10):928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Murabito JM. The epidemiology of longevity and exceptional survival. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:181–197. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S, Paradis S, Gottlieb S, Patterson G, Lee L, Tissenbaum H, Ruvkun G. The fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature. 1997;389:994–999. doi: 10.1038/40194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, Mukhopadhyay A, Svrzikapa N, Jiang F, Davis R, Tissenbaum H. JNK regulates lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulating nuclear translocation of forkhead transcription factor/DAF-16. PNAS. 2005;102:4494–4499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500749102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan CL, Peng CY, Chen CH, McIntire S. Genetic analysis of age-dependent defects of the Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons. PNAS. 2011;108:9274–9279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011711108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerbak C, Vayndorf E, Parker A, Neri C, Driscoll M, Taylor B. Insulin signaling in the aging of healthy and proteotoxically stressed mechanosensory neurons. Front Genet. 2014;5(212):1–14. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerbak C, Vayndorf E, Hernandez A, McGill C, Taylor B. Mechanosensory neuron aging: differential trajectories with lifespan-extending Alaskan berry and fungal treatments in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8(173):1–17. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Yue Y, Shen P, Yang JJ, Park Y. Cranberry product decreases fat accumulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Med Food. 2016;19(4):427–433. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2015.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank E, Rodgers K, Kenyon C. Spontaneous age-related neurite branching in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9279–9288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6606-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth M, et al. Neurite sprouting and synapse deterioration in the aging Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8778–8790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1494-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vayndorf EM, Scerbak C, Hunter S, Neuswanger JR, Toth M, Parker JA, Neri C, Driscoll M, Taylor BE. Morphological remodeling of C. elegans neurons during aging is modified by compromised protein homeostasis. Npj Aging Mech Dis. 2016;2:16001. doi: 10.1038/npjamd.2016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, Shukitt-Hale B, Kalt W, Ingram DK, Joseph JA, Wolkow CA. Blueberry polyphenols increase lifespan and thermotolerance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2006;5:59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DAF-16 and HSF-1 nuclear translocation are not induced after treatment with Alaskan berry or fungus treatment in day 3 adults. Representative images of age-matched, GFP-labeled DAF-16 (strain TJ356) or HSF-1 (strain OG497) day 3 adult (cultured at 20 °C) untreated positive and negative controls and 48-h treatment with lifespan-extending Alaskan berry and fungus treatments are shown. Notice the striking appearance of the positive controls for each strain when compared with other treatment groups. DAF-16::GFP positive control foci represent the translocation of DAF-16 from the cytosol to the nucleus while HSF-1::GFP positive control foci (within the larger nucleus) represent nuclear HSF-1 binding to DNA. DAF-16::GFP images (left panels) were collected at × 10 and HSF-1::GFP images (right panels) were collected at × 40 magnification. Positive control effects were induced by 30 min at 37 °C (DAF-16) or 35 °C (HSF-1). Scale bars represent 60 μm for the images in each column. (DOCX 607 kb)

DAF-16 translocates into the nucleus in day 9 adults treated with lowbush cranberry, but not blueberry or chaga treatments. Two representative images of each age-matched, GFP-labeled DAF-16 (strain TJ356) day 9 adult untreated positive and negative controls and 9 days of treatment with lifespan-extending treatments are shown. All animals were treated with lifespan-extending treatments of Alaskan botanicals (as listed in figure) from day 1 of adulthood until imaging at day 9 of adulthood. All individual animals shown are different from those shown in Fig. 1. Positive control effects were induced by 30 min at 37 °C. Alaskan berry and fungus treatments are shown. Yellow boxes mark the location of nuclear foci in treatment groups. All images were collected at × 10 magnification and the scale bar represents 60 μm for all of the images. (DOCX 471 kb)

Alaskan lowbush cranberry treatments lead to DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci formation later in life (day 9 adults). Box and whisker plot represents the number of DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci observed per lowbush cranberry treatment (50 and 400 μg/mL) in day 9 adults (quantified from images as in Supplemental Figure 2). Boxes represent the upper and lower quartile of animals per group, while the line in each box represents the median number of foci observed per treatment. There is one outlier in each of the cranberry treatment groups, represented by the unfilled circles. The untreated positive control treatment (heat shock) is omitted from this plot because there was no diffuse fluorescence observed in any head shock animals, indicating that most (if not all) cells in these individuals had DAF-16::GFP nuclear foci. (DOCX 51 kb)

HSF-1::GFP granule formation occurs in negative controls in old age. Representative images of age-matched, GFP-labeled HSF-1 (strain OG497) day 9 adult untreated positive and negative controls are shown. Notice the similar occurrence of granule formation (which represents HSF-1 binding to DNA) in both untreated negative control and heat shocked positive control animals, especially when compared to the positive control effect observed in young adults (shown in Supplemental Figure 1). All images were collected at × 40 magnification. Positive control effects were induced by 30 min at 35 °C. Scale bar represents 60 μm for all images. (DOCX 526 kb)

The effect of Alaskan berry and fungus treatments on daf-16(mgdf50) mutant lifespan. Survival curves showing the effect of Alaskan berry and fungus treatments on daf-16(mgdf50) mutant lifespan. Experimental results for Alaskan blueberry- (A–C), lowbush cranberry- (D–F), and chaga-treated (G–I) wildtype and DAF-16 mutant (daf-16(mgdf50)) C. elegans lifespan experiment trials are shown. All curves align with the survival data shown in Table 2. Approximately 50 animals represented per treatment (line) in each graph (exact sample sizes listed in Table 2). Note that D is the same survival curve shown in Fig. 2A. (DOCX 466 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.