Abstract

Here we investigated whether hydrogen can protect the lung from chronic injury induced by hypoxia/re-oxygenation (H/R). We developed a mouse model in which H/R exposure triggered clinically typical lung injury, involving increased alveolar wall thickening, infiltration by neutrophils, consolidation, alveolar hemorrhage, increased levels of inflammatory factors and recruitment of M1 macrophages. All these processes were attenuated in the presence of H2. We found that H/R-induced injury in our mouse model was associated with production of hydroxyl radicals as well as increased levels of colony-stimulating factors and circulating leukocytes. H2 attenuated H/R-induced production of hydroxyl radicals, up-regulation of colony-stimulating factors, and recruitment of neutrophils and M1 macrophages to lung tissues. However, H2 did not substantially affect the H/R-induced increase in erythropoietin or pulmonary artery remodeling. Our results suggest that H2 ameliorates H/R-induced lung injury by inhibiting hydroxyl radical production and inflammation in lungs. It may also prevent colony-stimulating factors from mobilizing progenitors in response to H/R-induced injury.

Introduction

Hypoxia/re-oxygenation (H/R) is common during acute exacerbation and remission of asthma, bronchiectasis and early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and it can result in pulmonary inflammatory response1 and aggravate existing lung disease. H/R increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the mitochondrial electronic transport chain1, NADPH oxidase2 and xanthine oxidase3. Under physiological conditions, ROS are produced at low levels to act as signaling messengers to maintain cellular functions4. Excessive production of ROS, particularly hydroxyl radicals as a result of H/R, oxidatively damages nucleic acids, lipids and proteins. ROS also induces polymorphonuclear leukocytes adhering to the pulmonary microcirculation5 to damage pulmonary epithelial cells6, vascular smooth muscle cells7, vascular endothelial cells8, and alveolar epithelial type II cells9. ROS in lung can initiate inflammatory responses by activating redox-sensitive transcription factors, including activator protein-1, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and nuclear factor-kappa B10,11, which up-regulate expression of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)12, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)13 and erythropoietin (EPO)14. These three factors may help initiate lung injury and pulmonary vascular remodeling by promoting lung inflammation15, increasing proliferation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells16. Besides, alveolar macrophage (AM) was reported as a critical promoter to orchestrate pulmonary H/R injury via up-regulation of proinflammatory factors17,18. In this way, H/R-induced pulmonary inflammation is characterized by the recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils and by up-regulation of proinflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-β and IL-619,20.

Hydrogen (H2) is a non-toxic, colorless, odorless and transparent gas that is easily reducible, so it can react directly with strong oxidants such as hydroxyl radical21. It exerts anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, pro-metabolic effects, and it can alter gene expression patterns22. It has shown therapeutic effects in animal models of Parkinson disease23, type 2 diabetes24, myocardial infarction25, acute hypoxia-induced brain injury26 and pulmonary infection27.

These results raise the question of whether H2 can attenuate H/R-induced lung injury. The present study explored this question using a mouse model of chronic H/R lung injury.

Results

H2 inhalation attenuates H/R-induced lung injury

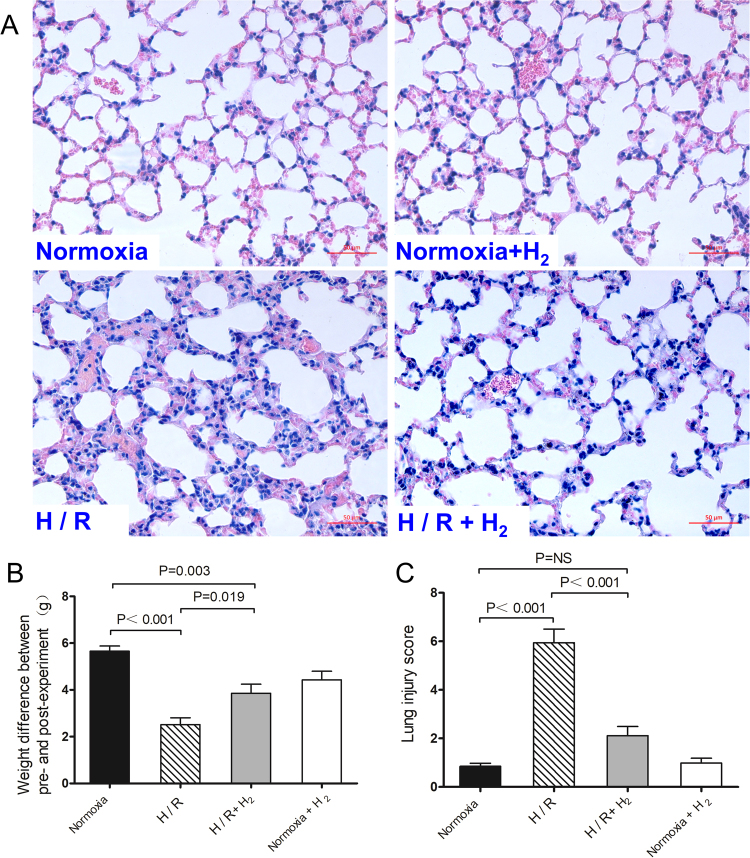

To investigate the effects of H2 on H/R-induced lung injury, male C57BL/6 mice 8 weeks old were exposed for 4 weeks (8 h per day) to hypoxia (10% O2, 90% N2), hypoxia combined with H2 (10% O2, 4% H2, 86% N2) or normoxia combined with H2 (21%O2, 4%H2, 75%N2), and then housed in normoxia for the other 16 h to allow re-oxygenation. Control mice were continuously exposed to normoxia (21% O2, 79% N2) for 4 weeks. After 4 weeks of H/R, significant lung injury appeared that was characterized by alveolar wall thickening, infiltration of neutrophils into lung interstitium and the alveolar space, consolidation, and alveolar hemorrhage (Fig. 1A). In H/R-exposed mice, lung injury score was significantly higher than in normoxia-treated mice (5.94 ± 1.96 vs. 0.85 ± 0.13, p < 0.001; Fig. 1C), and H/R-exposed animals experienced a smaller increase in body weight (5.65 ± 0.22 vs. 2.52 ± 0.30 g, p < 0.001; Fig. 1B). H2 significantly attenuated H/R-induced infiltration of inflammatory cells and alveolar wall thickening, and it significantly decreased lung injury score (2.11 ± 0.38, p < 0.001 vs. H/R). H2 also led to a larger increase in body weight in hypoxic mice (3.86 ± 0.39 g, p = 0.019 vs. H/R), although the weight of hypoxic mice was still lower than that of normoxia-treated mice (p = 0.003).

Figure 1.

Hydrogen inhalation reduced H/R-induced lung injury. Mice were exposed for 4 weeks (8 h per day) to hypoxia, hypoxia with 4% H2 or normoxia with 4% H2 and then housed in normoxia (16 h per day). Control mice were housed in normoxia (n = 10 in each group). (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of lung tissues. (B) Change in weight between before and after the experiment. (C) Lung injury scores. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data shown are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

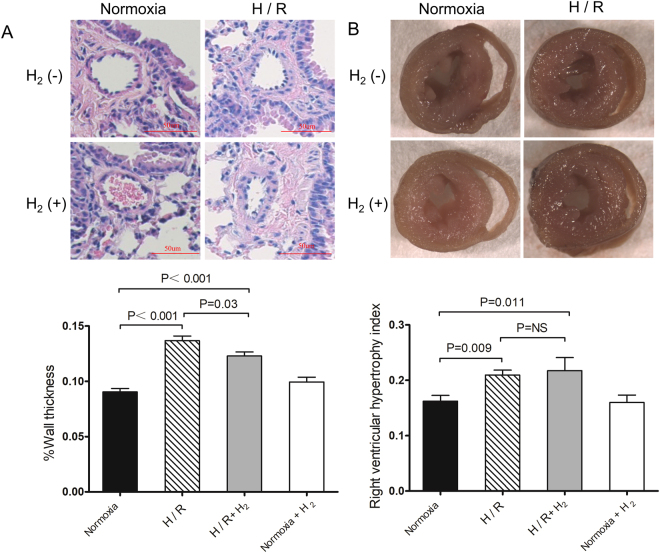

To evaluate the effect of H2 on pulmonary artery remodeling, we measured the percentage of medial wall thickening and right ventricular hypertrophy proliferative index (RHVI). The percentage of medial wall thickening significantly increased after 4 weeks of H/R (0.137 ± 0.004 vs. 0.090 ± 0.003 μm, p < 0.01; Fig. 2A), as did RHVI (0.209 ± 0.009 vs. 0.162 ± 0.010 g, p < 0.01; Fig. 2B). H2 slightly reduced H/R-induced medial wall thickening (0.123 ± 0.004 μm, p = 0.03 vs. H/R), but not H/R-induced RHVI (0.217 ± 0.023 g, p = 0.69 vs. H/R).

Figure 2.

Limited effect of hydrogen on H/R-induced pulmonary artery remolding. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 1 (n = 10 in each group). (A) Representative sections stained with hematoxylin-eosin (top) and percentage of wall thickness of pulmonary arterioles in the lungs (bottom). (B) Mouse hearts in cross section (top) and right ventricular hypertrophy index (see Methods) (bottom). Data shown are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

These results suggest that H2 attenuates lung injury, although it does not substantially affect pulmonary artery remodeling induced by H/R.

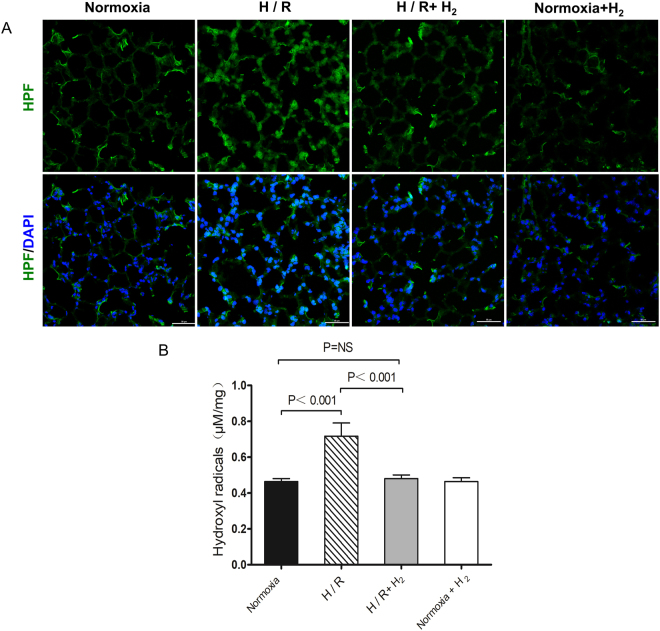

H2 inhalation reduces H/R-induced production of hydroxyl radicals

To begin to understand how H2 inhalation can protect lung from H/R-induced injury, tissue from exposed animals was sectioned and stained for hydroxyl radicals (Fig. 3A), levels of which were then quantified by chromatometry (Fig. 3B). H/R triggered a significant increase in hydroxyl radicals in lung tissue (0.72 ± 0.07 vs. 0.46 ± 0.02 μM/mg, p < 0.001 vs. normoxia), which was markedly lower in the presence of H2 (0.48 ± 0.02 μM/mg, p < 0.001 vs. H/R, p = 0.79 vs. normoxia).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of H/R-induced production of hydroxyl radicals by hydrogen. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 1 (n = 6 in each group). Lung samples were harvested, stained for hydroxyl radicals and quantitated. (A) Representative staining of lung tissue for hydroxyl radicals (original magnification, ×40). Sections were stained with hydroxyphenyl fluorescein solution and DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Quantitation of hydroxyl radicals in lung tissue. Data shown are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

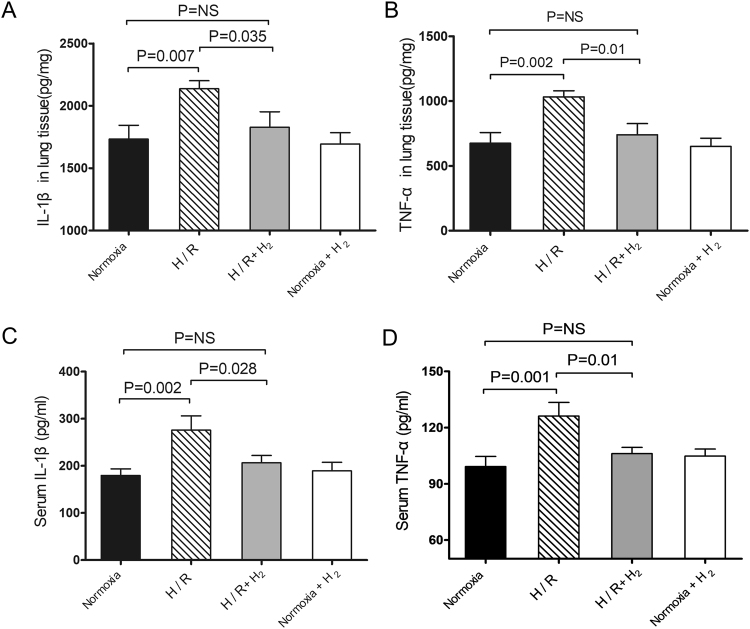

H2 inhalation attenuates both pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response

To verify the effect of H2 on lung and systemic inflammation induced by chronic H/R, inflammatory factors were assayed in lung tissue and serum. Lung tissue from H/R-exposed mice showed significantly higher levels of IL-1β and TNF-α than tissue from normoxia-exposed mice (IL-1β: 2137 ± 63 vs. 1734 ± 110 pg/mg; TNF-α: 1032 ± 48 vs. 675 ± 82 pg/mg; both p < 0.01 vs. H/R; Fig. 4A,B). Similar results were observed in serum (IL-1β: 276 ± 31 vs. 180 ± 14 pg/ml; TNF-α: 126 ± 7 vs. 99 ± 5 pg/ml; both p < 0.01 vs. hypoxia; Fig. 4C,D). H/R in the presence of H2 led to levels of IL-1β in lung tissue that were similar to those in normoxia-treated animals (1828 ± 124 pg/mg, p < 0.05 vs. H/R, p = ns vs. normoxia). Similar results were observed for levels of IL-1β in serum (206 ± 16 pg/ml), levels of TNF-α in lung tissue (740 ± 85 pg/ml) and levels of TNF-α in serum (106 ± 3 pg/ml) (all p < 0.05 vs. H/R, p = ns vs. normoxia; Fig. 4A–D).

Figure 4.

Down-regulation of pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses by hydrogen. Animals were treated as described in Fig. 1 (n = 10 in each group). The right lung was harvested and homogenized at the end of experiments. After centrifugation, supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-1β (A) and TNF-α (B) using commercial ELISA kits. Blood samples were also extracted and centrifuged for assaying IL-1β (C) and TNF-α (D) in serum. Data shown are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

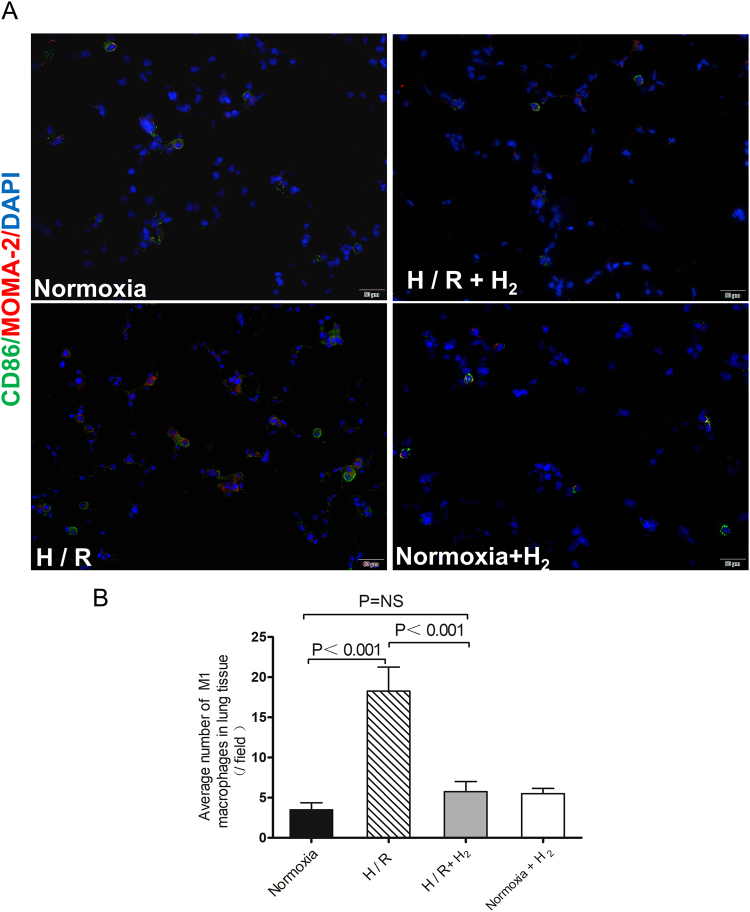

Since the primary source of inflammatory factors in the lung is thought to be pulmonary M1 macrophages, lung tissue from H/R-exposed animals was stained for M1 macrophages. These cells were abundant in lung tissue from animals exposed only to H/R, but they were rare in tissue from animals exposed to H/R in the presence of H2 and in tissue from normoxia-treated animals (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Staining (A) and quantitation (B) of M1 macrophages in the left lung. Animals were treated as described in Fig. 1 (n = 4 in each group). M1 macrophages were determined by immunofluorescence double staining with monocyte/macrophage marker (MOMA-2) and CD86. Sections were examined by confocal microscopy. The number of M1 macrophages in lung tissue was counted in one 200× field for each animal. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data shown are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

Our observation of increased levels of inflammatory factors, leukocytes, neutrophils and GM-CSF in circulation as a result of H/R suggests that this exposure induces a systematic inflammatory response, consistent with previous work28–30. Our results further suggest that H2 attenuates this response in mice.

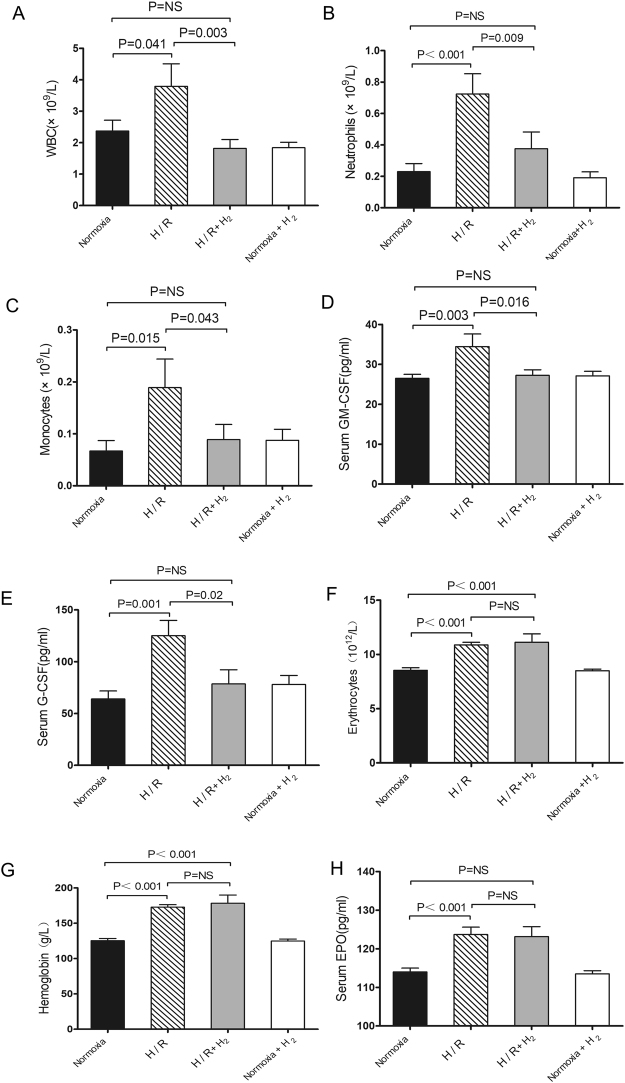

H2 inhibits up-regulation of G-CSF and GM-CSF without affecting EPO

H/R may exert its effects by up-regulation of the systems mediated by CSFs31 and EPO. Counts of the following cells were significantly higher in tissue from H/R-exposed animals than in tissue from normoxia-treated controls: leukocytes [(3.79 ± 0.72) × 109 vs. (2.38 ± 0.34) × 109/L, p = 0.026; Fig. 6A], neutrophils [(0.72 ± 0.13) × 109 vs. (0.23 ± 0.05) × 109/L, p < 0.001; Fig. 6B] and monocytes [(0.19 ± 0.05) × 109 vs (0.07 ± 0.02) × 109/L, p = 0.015; Fig. 6C]. H/R in the presence of H2 led to levels of these cells similar to those in normoxia-treated animals: leukocytes, (1.82 ± 0.28) × 109/L; neutrophils, (0.38 ± 0.11) × 109/L; and monocytes, (0.09 ± 0.03) × 109/L (all p < 0.05 vs. H/R, p > 0.05 vs. normoxia; Fig. 6A–C).

Figure 6.

H2 inhibits the H/R-induced increase in G-CSF and GM-CSF, but not H/R-induced up-regulation of the EPO-erythrocyte system. Mice were treated as in Fig. 1 (n = 10 in each group). Leukocytes (A), neutrophils (B), monocytes (C), erythrocytes (F) and hemoglobin (G) were assayed using an automatic blood analyzer. Serum levels of G-CSF (C), GM-CSF (D), and EPO (H) were assayed using commercial ELISA kits. Data shown are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

H/R also led to significantly higher serum levels of GM-CSF than normoxia (34.46 ± 0.15 vs. 26.50 ± 0.98 pg/ml), as well as significantly higher levels of G-CSF (125.08 ± 14.76 vs. 64.03 ± 7.72 pg/ml; both p < 0.05; Fig. 6D–E). H/R in the presence of H2 led to levels of GM-CSF (27.26 ± 1.37 pg/ml) and G-CSF (78.57 ± 13.63 pg/ml) similar to those in normoxia-treated animals (all p < 0.05 vs. H/R, p > 0.05 vs. normoxia).

H/R led to significantly higher levels of EPO than normoxia (123.66 ± 1.90 vs. 114.00 ± 0.98 pg/ml), as well as significantly higher numbers of erythrocytes [(10.87 ± 0.24) × 1012 vs. (8.53 ± 0.24) × 1012/L] and hemoglobin levels (172.86 ± 3.44 vs. 125.27 ± 3.12 g/L; all p < 0.05; Fig. 6F–H). Levels after hypoxia in the presence of H2 were similar to those after H/R without H2: EPO, 123.15 ± 2.56 pg/ml; erythrocytes, (11.12 ± 0.78) × 1012/L; hemoglobin, 178.38 ± 11.63 g/L (all p > 0.05 vs. H/R).

These results suggest that inhaled H2 inhibits H/R induction of the CSF system but not of the EPO system.

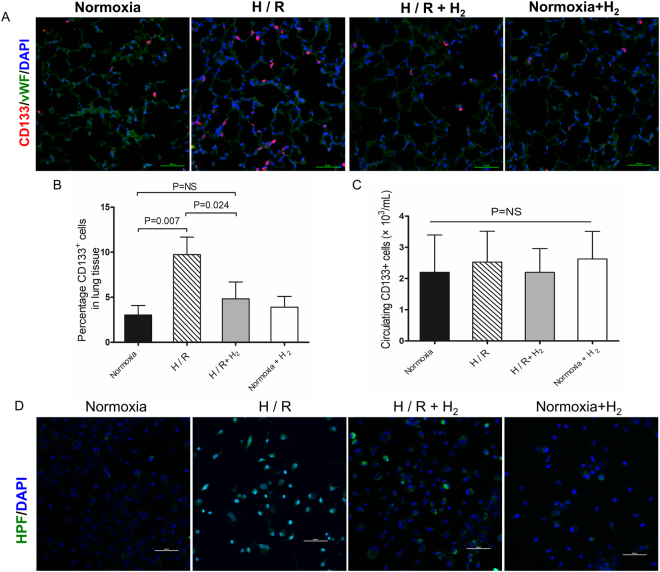

H2 protects CD133+ progenitors from H/R-induced injury

Because G-CSF can mobilize progenitors from bone marrow, which home to sites of injury to mount anti-inflammatory and repair responses32, we wanted to test whether H/R mobilizes progenitors that home to lung tissue. Therefore, we investigated pulmonary and circulating CD133+ progenitors, which are pluripotential cells that can be mobilized by G-CSF33. These cells were abundant in lung tissues after H/R exposure, while they were rare in mice exposed to hypoxia in the presence of H2 and in normoxia-treated mice (Fig. 7A). Flow cytometry showed significantly higher percentages of pulmonary CD133+ progenitors in H/R-exposed mice (9.73 ± 1.95%) than in normoxia-treated mice (3.03 ± 1.06%, p = 0.007) and mice exposed to H/R in the presence of H2 (4.83 ± 1.87%, p = 0.024 vs. H/R, p > 0.05 vs. normoxia; Fig. 7B). In contrast, percentages of circulating CD133+ cells were similar among the various animal groups (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Effect of hydrogen on CD133+ progenitors. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 1 (n = 4 in each group). Lung samples were harvested for CD133+ cell staining (A) and counting (B). Blood samples were extracted and CD133+ cells were counted (C). (D) Cultured CD133+ progenitors were stained with hydroxyphenyl fluorescein solution and DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data shown are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

Next we tested the effects of H/R and H2 on progenitors. Cultures of mouse CD133+ progenitors were exposed for 8 h at 37 °C to hypoxia (10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) or hypoxia in the presence of H2 (10% O2, 5% CO2, 4% H2, 81% N2). Control cultures were exposed to normoxia (5% CO2, 95% air) or normoxia in the presence of H2 (5% CO2, 21% O2, 4% H2, 70% N2). Levels of hydroxyl radicals were higher in cells exposed to hypoxia than in cells treated with normoxia, and most of the radicals colocalized with DAPI in the nucleus (Fig. 7D). H2 reduced the levels of hydroxyl radicals, especially those in the nucleus.

Our results suggest that H/R induces the homing of CD133+ progenitors to lung tissue, presumably to repair damage. H2 helps protect CD133 + progenitors from H/R injury by inactivating hydroxyl radicals.

Discussion

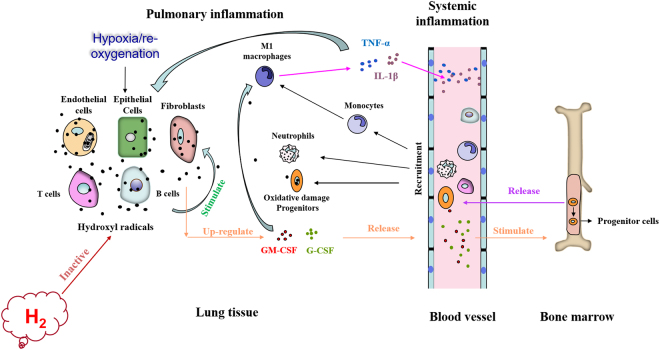

In this study, we found that mice exposed to chronic H/R exhibited significant lung injury, which was significantly improved by 4% H2 inhalation. H2 treatment inhibited the generation of hydroxyl radicals and down-regulated GM-CSF and G-CSF, which may attenuate infiltration by neutrophils and M1 macrophages, as well as release of proinflammatory factors. H2 may also protect the progenitor cells by inactivating hydroxyl radicals (Fig. 8). Our results demonstrate that molecular hydrogen is effective at protecting lung from H/R-induced injury.

Figure 8.

Mechanisms by which inhaled H2 may alleviate H/R-induced lung injury. H/R increases hydroxyl radicals, which may activate various cell types, such as epithelial cells, fibroblasts, T cells, B cells, neutrophils and macrophages. The net result is up-regulation of colony-stimulating factors, which stimulate the release of leukocytes and progenitors from bone marrow, which migrate into inflamed lung tissue. In lung tissue, infiltrated leukocytes and monocytes follow M1 polarization and release proinflammatory factors, which increase the secretion of colony-stimulating factors. The ability of infiltrated progenitors to repair lung tissue is compromised. H2 inactivates hydroxyl radicals induced by H/R, which down-regulates colony-stimulating factors, thereby inhibiting release of leukocytes from bone marrow and their infiltration into lung tissues. The repair ability of progenitors may also improve.

Our results showed that H/R triggered massive generation of hydroxyl radicals, similar to previous reports34, and that H2 inhalation reduced these levels, likely reflecting the established ability of H2 to inactivate hydroxyl radicals22,35. The decrease in hydroxyl radicals was associated with reduction of GM-CSF and G-CSF, followed by down-regulation of systemic and pulmonary inflammatory responses. These results suggest that H/R-induced production of hydroxyl radicals is important for up-regulating CSFs, which can be abolished by H2 inhalation.

CSFs are important mediators of both systemic and tissue inflammation, but their role in H/R-induced lung injury has been unclear. GM-CSF and G-CSF can be secreted from various cell types, including epithelial cells, fibroblasts36, T cells, B cells37, neutrophils and macrophages38 under the stimulation of IL-1β and TNF-α12,15. Studies have shown that CSFs, especially GM-CSF, aggravate inflammation39 by enhancing proinflammatory cytokine production40 and mobilizing leukocytes, promoting their survival, proliferation41, differentiation42, and stimulating their activation43–45 and migration. Recent studies show that GM-CSF blockade has a therapeutic effect against cardiac inflammation during Kawasaki disease or aortic aneurysm formation46, as well as against lung diseases such as COPD47, interstitial lung disease48, allergy49and asthma50. Furthermore, GM-CSF promotes macrophage polarization toward M1-skewed cells51 and stimulates macrophage plasminogen activator activity52, which may induce up-regulation of pro-inflammatory factors. Both M1 macrophages and neutrophils may aggravate lung and systemic inflammation by releasing proinflammatory factors and elastase. In the present study, we found that H/R increased serum levels of both GM-CSF and G-CSF, which was followed by increases in leukocytes and pro-inflammatory factors in circulation and lung tissues. In addition, M1 macrophages accumulated in the lung tissues. These findings suggest that CSFs are key mediators of H/R-induced lung injury.

G-CSF not only promotes inflammation, but also mobilizes stem cells derived from bone marrow for repair53. To assess the role of these cells in H/R-induced lung injury, we analyzed CD133+ cells, a homogeneous population with multi-proliferative potential previously shown to play a role in lung repair54,55. We found that H/R triggered accumulation of CD133+ progenitors, although this did not seem to prevent lung tissue from H/R injury. In our experiments with CD133+ progenitor cultures, hypoxia significantly increased hydroxyl radicals. It is possible that these radicals cause oxidative injury in the progenitors, damaging their ability to repair tissue. This implies that H2 improves progenitor function by inactivating hydroxyl radicals in those cells. This may be another reason for the protective effects of H2.

In our experiments, chronic H/R increased the level of EPO in serum, which increases red blood cell count and blood viscosity, thereby aiding pulmonary artery remodeling in response to chronic H/R56. However, H2 inhalation in our mouse model of H/R-induced injury did not influence the EPO-red blood cell system, nor did it significantly affect pulmonary artery remodeling or right ventricular hypertrophy. These results suggest hydroxyl radicals activate the CSF system but not the EPO-red blood cell system.

In conclusion, our study shows that H2 protects lung from H/R-induced injury, at least in part by scavenging hydroxyl radicals, thereby inhibiting lung inflammation induced by G-CSF and GM-CSF. This helps protect CD133+ progenitors from oxidative damage. Because inhalation of 1–4% H2 appears to show no cytotoxicity35, consistent with what we found in this study, our results justify further work toward developing H2 as a treatment against H/R-induced lung injury, such as during acute exacerbation and remission of asthma, bronchiectasis and early COPD.

Materials and Methods

Animal

Male C57BL/6 mice 8 weeks old were provided by the Sichuan Provincial Experimental Animal Center. The H/R model was established as follows. Mice were placed in a closed container with inlet and outlet ports on the two sides. Sodium lime was placed at the bottom of the container to absorb CO2. Animals were exposed to hypoxia (10% O2, 90% N2), hypoxia in the presence of H2 (10% O2, 4% H2, 86% N2), or normoxia (21% O2, 79% N2) in the presence of H2 (21% O2, 4% H2, 75% N2) (8 h per day). Then they were exposed to air for re-oxygenation (16 h per day) for 4 weeks. Control mice were exposed to normoxia (21% O2, 79% N2) for 4 weeks. Mice had free access to water and conventional laboratory diet throughout the exposure.

Hydrogen (purity >99.9%) was generated using a hydrogen generator (Beijing Zhongxing Huili Technology Development, Beijing, China). During experiments, the O2 and CO2 concentrations were monitored using a Philips Airway Gases monitor, and H2 concentration was monitored using a STP1000 Multiplexed Gas Analyzer (T & P Union (Beijing), Beijing, China).

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of Sichuan University and were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan University.

Blood cell count

Blood samples were taken from the apical artery, and blood cells were counted using an automatic blood analyzer (Sysmex-XE5000, Toagosei Co., Ltd, Yokohama, Japan).

Lung histological injury

The lung was harvested and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined under a light microscope by pathologist blinded to the experimental groups. Severity of lung injury was scored using a 5-point scale57 (0 = normal histology, 5 = most severe injury) that took into account the parameters of alveolar congestion, hemorrhage, neutrophil accumulation in the airspace or vessel wall, alveolar wall thickness, and hyaline membrane formation. We chose 10 images for each animal randomly, and parameter values were averaged for the 10 images. The average values of all parameters were then added together to generate a total lung injury score. Scoring was performed by two pathologists in a blinded fashion, and the two scores for a given animal were averaged to obtain the final score for that animal.

Measurement of factors

Blood samples from the apical artery were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain serum. To obtain lung tissues, lung was harvested on ice immediately after euthanasia and weighed. An aliquot of tissue (50 mg) was cut into 1-mm3 pieces, added to 500 μl PBS and homogenized. Samples were left on ice for 5 min and centrifuged at 3500 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Levels of EPO, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-1β and TNF-α in serum and lung tissue supernatant were assayed using commercial ELISA kits (Neobioscience Technology, Beijing, China).

Evaluation of vascular remodeling and right ventricle hypertrophy

Pulmonary artery remodeling was assessed in terms of percent medial thickness, which was calculated according to the equation: (medial wall thickness × 2)/vessel diameter ×100%58. Only vessels with a circular appearance and external diameter between 50 and 100 μm were used. Lung sections were examined by an investigator blinded to experimental treatment using an Olympus-BHS microscope.

Right ventricular hypertrophy was quantified by calculating the ratio of right ventricle to left ventricle plus septum weight [RV/(LV + S)]. The ventricles and septum were collected, and the wet and dry ventricle and septal weights were obtained by drying for 24 h at 60 °C.

Hydroxyl radical stains and measurements

Frozen sections (5 μm) of the right lung were used. Hydroxyphenyl fluorescein solution (Sigma, USA) was diluted 1:500 and added to the lung tissue section for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI; Invitrogen, USA). Images were analyzed by confocal microscopy.

To quantify hydroxyl radicals, lung tissue (100 mg) was ground up in liquid nitrogen, added to 500 ul PBS and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and analyzed as quickly as possible using a commercial colorimetric kit (Genmed, Scientifics, USA).

Immunofluorescence

After 4-week H/R, the right lung was harvested and cut into frozen sections (5 μm), which were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, and blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma, USA) in PBS.

For detecting progenitors, rabbit anti-CD133 antibody conjugated to AF555 (Bioss, Beijing, China) and rabbit anti-Von Willebrand factor antibody conjugated to AF488 (Bioss) were used at a dilution of 1:100.

For detecting M1 macrophage in lung, sections were incubated at 4 °C overnight with rabbit anti-mouse CD86 antibody (1:100; Genetex, USA) and rat anti-mouse MOMA-2 antibody (1:50; Genetex, USA). Then the sections were washed in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or 555 (1:200; Biofroxx, Germany). As a negative control, sections were incubated with PBS instead of primary antibody. Sections were stained with DAPI (Invitrogen) to label nuclei. Images were then visualized using a fluorescence microscope (LSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 20×/0.75D objective.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD133+ progenitors

Blood was diluted 1:1 with Hank’s solution, layered onto the top of a mononuclear cell separation solution, and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 35 min at 4 °C. The white mononuclear cell loop was obtained, washed with PBS, and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with anti-CD133 antibody conjugated to AF555 (Bioss). Then cells were washed twice, re-suspended in 500 μl PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry on an Esp Elite device (Beckman Coulter, Chicago, IL, USA). PBS served as a negative control.

For determining pulmonary CD133+ cells, harvested lung tissues were placed in 2 ml PBS and 1 mg/ml LiberaseTM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Tissues were minced with scissors, and digested for 30 min at 37 °C before filtration through a 70-μm cell strainer and red blood cell lysis. Samples were then filtered through a 40-μm filter and resuspended, after which CD133+ cells were analyzed as described above.

Cell culture

Bone marrow was collected as described59 by flushing the femurs and tibias of 2-month-old C57BL/6 mice with complete DMEM-LG medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Cells were cultured for 24 h in a Petri dish (Thermo Fisher Scientific), then non-adherent cells were removed by washing with PBS. Adherent cells were further cultured in complete medium and retrieved by trypsinization with 0.25% trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 min at 37 °C. Treated adherent cells were cultured and passaged three times. Third-passage CD133+ cells were retrieved using immunomagnetic microbeads, and further cultured in complete medium. Cultured cells were retrieved, and their morphology and ability to differentiate into osteoblasts and adipocytes were examined.

CD133+ cells were split into four Petri dishes (2 × 105 cells/dish) and cultivated in standard medium composed of MEM alpha (20% fetal bovine serum(FBS) +1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for two days, and then incubated for 8 h at 37 ◦C in a hypoxic atmosphere (10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) or a hypoxic atmosphere containing H2 (10% O2, 5% CO2, 4% H2, 81% N2). Control cultures were incubated in a normoxic atmosphere (5% CO2, 95% air) or a normoxic atmosphere containing H2 (5% CO2, 21% O2, 4% H2, 70% N2). After the 8 h incubation, hydroxyphenyl fluorescein solution (1:500) and Hoechst (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to cultures, which were returned to their incubators for another 30 min. Then cultures were washed with PBS, centrifuged under normoxic conditions and analyzed using confocal microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0 (IBM, Chicago, USA). Results were reported as mean ± SEM. Differences between more than two groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA. The threshold for significance in all statistical tests was p < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jiezhen Huang for her assistance with animal experiments. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570374).

Author Contributions

D.T., M.C. and J.Z. contributed to the conception and design of this study. L.D., Y.Q. and Z.L. contributed to data acquisition. M.C., S.Z. and Y.C. carried out animal experiments. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. M.C., J.Z. and L.D. drafted the manuscript and critically revised it for important intellectual content. M.C. Y.C. and J.Z. helped with immunofluorescence staining, ELISAs and cell culture. All authors commented on the manuscript and approved the final version to be submitted.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Meihong Chen and Jie Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Korge P, Ping P, Weiss JN. Reactive oxygen species production in energized cardiac mitochondria during hypoxia/reoxygenation: modulation by nitric oxide. Circ Res. 2008;103(8):873–880. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.180869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao MH, Dai W, Li YJ, Hu CP. Rutaecarpine prevents hypoxia-reoxygenation-induced myocardial cell apoptosis via inhibition of NADPH oxidases. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;89(3):177–186. doi: 10.1139/Y11-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratych RE, Chuknyiska RS, Bulkley GB. The primary localization of free radical generation after anoxia/reoxygenation in isolated endotelial cells. Surgery. 1987;102(2):122–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauer H, Wartenberg M, Hescheler J. Reactive oxygen species as intracellular messengers during cell growth and differentiation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2001;11(4):173–86. doi: 10.1159/000047804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiles ME, et al. Hypoxia reoxygenation-induced injury of cultured pulmonary microvessel endothelial cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53(5):490–497. doi: 10.1002/jlb.53.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Na N, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are required for hypoxia-induced degradation of keratin intermediate filaments. FASEB J. 2010;24(3):799–809. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene EL, et al. 5-HT(2A) receptors stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase via H(2)O(2) generation in rat renal mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278(4):F650–F658. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.4.F650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali MH, et al. Endothelial permeability and IL-6 production during hypoxia: role of ROS in signal transduction. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(5 Pt 1):L1057–1065. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.5.L1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee IT, Yang CM. Role of NADPH oxidase/ROS in pro-inflammatory mediators-induced airway and pulmonary diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84(5):581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park HS, Kim SR, Lee YC. Impact of oxidative stress on lung diseases. Respirology. 2009;14(1):27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman I, MacNee W. Regulation of redox glutathione levels and gene transcription in lung inflammation: therapeutic approaches. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28(9):1405–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00215-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton JA. Colony-stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(7):533–544. doi: 10.1038/nri2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazett M, et al. Attenuating immune pathology using a microbial-based intervention in a mouse model of cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0577-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maiese K, Li F, Chong ZZ. New avenues of exploration for erythropoietin. JAMA. 2005;293(1):90–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becher B, Tugues S, Greter M. GM-CSF: From Growth Factor to Central Mediator of Tissue Inflammation. Immunity. 2016;45(5):963–973. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Meer. P, et al. Prognostic value of plasma erythropoietin on mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(1):63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naidu BV, et al. Regulation of chemokine expression by cyclosporine A in alveolar macrophages exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(3):899–905. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03746-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCourtie AS, et al. Alveolar macrophage secretory products augment the response of rat pulmonary artery endothelial cells to hypoxia and reoxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(3):1056–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matuschak GM, et al. Upregulation of postbacteremic TNF-alpha and IL-1alpha gene expression by alveolar hypoxia/reoxygenation in perfused rat lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(2):629–637. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.9707120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ala Y, et al. Hypoxia/reoxygenation stimulates endothelial cells to promote interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 production. Effects of free radical scavengers. Agents Actions. 1992;37(1-2):134–139. doi: 10.1007/BF01987902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki Y, et al. Hydrogen-rich pure water prevents cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema in SMP30 knockout mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;492(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohta S. Molecular hydrogen as a preventive and therapeutic medical gas: initiation, development and potential of hydrogen medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;144(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujita K, et al. Hydrogen in drinking water reduces dopaminergic neuronal loss in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamimura N, et al. Molecular hydrogen improves obesity and diabetes by inducing hepatic FGF21 and stimulating energy metabolism in db/db mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(7):1396–1403. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asanuma H, Kitakaze M. Translational Study of Hydrogen Gas Inhalation as Adjuncts to Reperfusion Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ J. 2017;81(7):936–937. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W, et al. Protective effects of hydrogen on fetal brain injury during maternal hypoxia. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;111:307–311. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie K, et al. Molecular hydrogen ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice through reducing inflammation and apoptosis. Shock. 2012;37(5):548–55. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31824ddc81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramadass M, Johnson JL, Catz SD. Rab27a regulates GM-CSF-dependent priming of neutrophil exocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;101(3):693–702. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3AB0416-189RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piper C, et al. T cell expression of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in juvenile arthritis is contingent upon Th17 plasticity. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(7):1955–1960. doi: 10.1002/art.38647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du L, et al. Actin filament reorganization is a key step in lung inflammation induced by systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(5):597–603. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0094OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Nieuwenhuijze A, et al. GM-CSF as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Mol Immunol. 2013;56(4):675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bi LY, et al. Effects of autologous SCF- and G-CSF-mobilized bone marrow stem cells on hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in rats with ischemia-reperfusion renal injury. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(2):4102–4112. doi: 10.4238/2015.April.27.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin W, et al. Comparison between CD271 and CD133 used for immunomagnetic positive sorting enriching in mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2008;16(2):333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu G, et al. Hypoxia and reoxygenation-induced oxidant production increase in microvascular endothelial cells depends on connexin40. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(6):1008–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohsawa I, et al. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat Med. 2007;13(6):688–694. doi: 10.1038/nm1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton JA, et al. Cytokine regulation of colony-stimulating factor (CSF) production in cultured human synovial fibroblasts. II. Similarities and differences in the control of interleukin-1 induction of granulocyte-macrophage CSF and granulocyte-CSF production. Blood. 1992;79(6):1413–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li R, et al. Proinflammatory GM-CSF-producing B cells in multiple sclerosis and B cell depletion therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(310):310ra166. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darrieutort-Laffite C, et al. IL-1β and TNFα promote monocyte viability through the induction of GM-CSF expression by rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:241840. doi: 10.1155/2014/241840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hierholzer C, et al. G-CSF instillation into rat lungs mediates neutrophil recruitment, pulmonary edema, and hypoxia. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63(2):169–174. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleetwood AJ, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF) and macrophage CSF-dependent macrophage phenotypes display differences in cytokine profiles and transcription factor activities: implications for CSF blockade in inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178(8):5245–5252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgess AW, et al. Purification and properties of colony-stimulating factor from mouse lung-conditioned medium. J Biol Chem. 1977;252(6):1998–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiomi A, Usui T. Pivotal roles of GM-CSF in autoimmunity and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:568543. doi: 10.1155/2015/568543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metcalf D. Hematopoietic cytokines. Blood. 2008;111(2):485–491. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell IK, et al. Therapeutic Targeting of the G-CSF Receptor Reduces Neutrophil Trafficking and Joint Inflammation in Antibody-Mediated Inflammatory Arthritis. J Immunol. 2016;197(11):4392–4402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang P, et al. The effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and neutrophil recruitment on the pulmonary chemokine response to intratracheal endotoxin. J Immunol. 2001;166(1):458–465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stock AT, et al. GM-CSF primes cardiac inflammation in a mouse model of Kawasaki disease. J Exp Med. 2016;213(10):1983–1998. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vlahos R, et al. Therapeutic potential of treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by neutralising granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112(1):106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiomi A, et al. GM-CSF but not IL-17 is critical for the development of severe interstitial lung disease in SKG mice. J Immunol. 2014;193(2):849–859. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willart MA, et al. Interleukin-1α controls allergic sensitization to inhaled house dust mite via the epithelial release of GM-CSF and IL-33. J Exp Med. 2012;209(8):1505–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamashita N, et al. Attenuation of airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine asthma model by neutralization of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) Cell Immunol. 2002;219(2):92–97. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8749(02)00565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krausgruber T, et al. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(3):231–238. doi: 10.1038/ni.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verreck FA, et al. Human IL-23-producing type 1 macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(13):4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400983101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeLuca E, et al. Prior chemotherapy does not prevent effective mobilisation by G-CSF of peripheral blood progenitor cells. Br J Cancer. 1992;66(5):893–839. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aliotta JM, et al. Stem cells and pulmonary metamorphosis: new concepts in repair and regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204(3):725–741. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Le BK, Ringdén O. Mesenchymal stem cells: properties and role in clinical bone marrow transplantation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(5):586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hasegawa J, et al. Altered pulmonary vascular reactivity in mice with excessive erythrocytosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(7):829–835. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1154OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bastarache JA, et al. Low levels of tissue factor lead to alveolar haemorrhage, potentiating murine acute lung injury and oxidative stress. Thorax. 2012;67(12):1032–9. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hashimoto-Kataoka T, et al. Interleukin-6/interleukin-21 signaling axis is critical in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(20):E2677–2686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424774112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tropel P, et al. Isolation and characterisation of mesenchymal stem cells from adult mouse bone marrow. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295(2):395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]