Abstract

Successful inter-host transmission of most apicomplexan parasites requires the formation of infective sporozoites within the oocysts. Unlike all other infective stages that are strictly intracellular and depend on host resources, the sporozoite stage develops outside the host cells, but little is known about its self-governing metabolism. This study deployed Eimeria falciformis, a parasite infecting the mouse as its natural host, to investigate the process of phospholipid biogenesis in sporozoites. Lipidomic analyses demonstrated the occurrence of prototypical phospholipids along with abundant expression of at least two exclusive lipids, phosphatidylthreonine (PtdThr) and inositol phosphorylceramide with a phytosphingosine backbone, in sporozoites. To produce them de novo, the parasite harbors nearly the entire biogenesis network, which is an evolutionary mosaic of eukaryotic-type and prokaryotic-type enzymes. Notably, many have no phylogenetic counterpart or functional equivalent in the mammalian host. Using Toxoplasma gondii as a gene-tractable surrogate to examine Eimeria enzymes, we show a highly compartmentalized network of lipid synthesis spread primarily in the apicoplast, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondrion, and Golgi complex. Likewise, trans-genera complementation of a Toxoplasma mutant with the PtdThr synthase from Eimeria reveals a convergent role of PtdThr in fostering the lytic cycle of coccidian parasites. Taken together, our work establishes a model of autonomous membrane biogenesis involving significant inter-organelle cooperation and lipid trafficking in sporozoites. Phylogenetic divergence of certain pathways offers attractive drug targets to block the sporulation and subsequent transmission. Not least, our results vindicate the possession of an entire de novo lipid synthesis network in a representative protist adapted to an obligate intracellular parasitic lifestyle.

Introduction

The protozoan phylum Apicomplexa comprises >6000 extant species of obligate intracellular parasites, many of which infect a wide range of organisms including livestock and humans1. Some of the prevalent and representative apicomplexan parasites of the mammalian hosts include Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, Eimeria and Cryptosporidium. The genus Eimeria represents the largest clade in the phylum Apicomplexa; it consists of >1800 species, most of which infect a specific host2. These parasites together impose a significant healthcare burden and socioeconomic impact globally. Most apicomplexans have complex lifecycles occurring in one or more host organisms. The natural lifecycle comprises asexual and sexual reproduction gyrating often between the primary (sexual) and secondary (asexual) hosts. Infective stages of apicomplexans are termed zoites, which are formed either after sexual (sporozoite) or asexual (tachyzoite, merozoite etc.) reproduction. The lifecycle begins with the transmission of sporozoites developing within sporulated oocysts following the completion of sexual reproduction. A single oocyst yields 4 (Cryptosporidium), 8 (Toxoplasma, Eimeria) or numerous (Plasmodium) sporozoites after sporogony. Unlike other infectious stages that parasitize corresponding host cells to ensure survival and reproduction, sporozoite development occurs extracellularly and does not involve intimate interactions with host cells.

The formation of apicomplexan zoites obliges considerable lipid biogenesis when parasites replicate inside a parasitophorous vacuole (PV) enclosed within a host cell, or within oocysts. Previous studies on Toxoplasma tachyzoites and Plasmodium merozoites have demonstrated that these parasites not only deploy host-derived precursors to synthesize the required phospholipids3–9, but also are competent in salvaging selected lipids from the sheltering host cells10–12. It remains enigmatic how freely developing sporozoites satisfy their phospholipid demands being outside the host milieu. Moreover, from a conceptual viewpoint, the sporozoite stage imparts an excellent model to evaluate the “actual” metabolic potential of otherwise host-dependent organisms. The sporozoite metabolism has nonetheless been a black box from any typical apicomplexan parasite, principally because it is challenging to attain sufficient amounts of sporozoites for downstream biochemical analyses from non-model hosts.

De novo synthesis of the main phospholipids commences with the assembly of lysophosphatidic acid (Lyso-PtdOH) and phosphatidic acid (PtdOH) using glycerol 3-phosphate (Glycerol-3P) and fatty acids (Figure S1). In prokaryotes, PtdOH is converted into CDP-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) that serves as a substrate to synthesize all phospholipids13. In eukaryotes, PtdOH functions as a precursor for both CDP-DAG and diacylglycerol (DAG), which subsequently drive syntheses of distinct phospholipid classes13. CDP-DAG is utilized to make phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) and phosphatidylglycerol (PtdGro), while DAG enables the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) via the CDP-choline or CDP-ethanolamine pathways, respectively. PtdEtn can also be made by decarboxylation of phosphatidylserine (PtdSer), which itself is either derived by a base-exchange reaction from PtdEtn or PtdCho (mammals) or produced by fusion of CDP-DAG and serine (yeast)14. In some eukaryotic cells, such as yeast and mammalian hepatocytes, PtdEtn can also be methylated to yield PtdCho. In addition to the aforementioned archetypal lipid network, apicomplexan pathogens have evolved many novel and often physiologically essential pathways. Some of them have originated by secondary endosymbiosis of their common ancestor with a red alga15–19. Recently, we have identified a unique lipid, termed phosphatidylthreonine (PtdThr), in Toxoplasma gondii, which is crucial for calcium homeostasis governing the lytic cycle7,20,21. Such divergent or parasite-specific lipid synthesis pathways offer therapeutic targets to selectively inhibit the parasite reproduction.

This study employed Eimeria falciformis, a monoxenous (single-host) parasite infecting mouse, to discern the metabolic design of sporozoites22–24. We reveal a highly compartmentalized network of lipid synthesis, enabling sporozoites to produce generic as well as exclusive phospholipids in a self-sustained manner. The natural presence of atypical lipids together with autonomous biogenesis and evolutionary divergence of certain pathways offer a unique opportunity to prevent the process of sporulation and thereby inter-host transmission.

Results

The lipid profile of Eimeria sporozoites differs markedly from Toxoplasma tachyzoites

To examine the phospholipid composition of E. falciformis sporozoites, we isolated total lipids from purified parasites and performed high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). By this procedure, lipids were separated primarily based on their head-group (although some species resolution can be observed, Fig. 1a), thus eliminating any confusion between isobaric lipids from different classes. The total lipids extracted from the tachyzoites of T. gondii, which served as a comparative reference, were also analyzed alongside. The most abundant phospholipid detected in sporozoites was PtdCho (79.3%), followed by PtdEtn (13.1%), PtdThr (5.8%), PtdIns (1.3%), PtdSer (0.5%) and PtdGro (0.04%), whereas the dominant sphingolipid is inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC) (Fig. 1a). T. gondii tachyzoites shared similar phospholipid classes with E. falciformis sporozoites, but possessed ethanolamine phosphorylceramide (EPC) and sphingomyelin (SM) instead of IPC as the major sphingolipids, as also reported previously7,25 (Fig. 1a). The main PtdThr peak of E. falciformis appeared at a later retention time than the one of T. gondii, which indicated the presence of different species in these two parasites. Quantification of lipids based on calibration curves using standard lipids showed that E. falciformis sporozoites harbor more PtdCho and PtdEtn, but less PtdIns and PtdSer than T. gondii tachyzoites (Fig. 1b). Collectively, Eimeria contains significantly more phospholipids per cell than T. gondii, which is likely due to the bigger size of sporozoites than tachyzoites (10–12 vs. 7–8 μm)24.

Fig. 1. E. falciformis sporozoites and T. gondii tachyzoites share most phospholipid classes, but show a remarkably different composition of individual species.

a Representative base peak chromatograms showing the retention times and relative intensities of lipid classes of E. falciformis sporozoites and T. gondii tachyzoites. b Amounts of major glycerophospholipids expressed in E. falciformis and T. gondii. The numerical values show the mean with SEM from 3 independent assays (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). c Colored spectra comparing the composition of major glycerophospholipid species between the two parasitic stages. Color-coding shows the number of carbons and degree of saturation in acyl chains bound to indicated lipids, as confirmed by MS/MS. Percentages of the three most abundant species in each lipid class are shown on the corresponding bars. The data show the mean of 3 independent assays. Note that error bars are not depicted to avoid further complexity. d Average high-field orbitrap mass spectrum showing accurate masses during the elution of IPC, isolated from sporozoites of Eimeria. Peaks are annotated with the best database matches, together with the corresponding mass errors in parenthesis. In accordance with current nomenclature, the total number of carbon atoms (xx), the number of double bonds (yy), and the number of hydroxyl groups (zz) in the ceramide part of the molecule are depicted as “xx:yy;zz”. The corresponding structure of the most abundant species and its fragmentation in both positive and negative ion mode is given in Supplementary Figure S2

Online tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis of HPLC-eluted phospholipids revealed that the acyl chain compositions of different species were much more uniform in sporozoites compared to tachyzoites. The most abundant species in each phospholipid class of tachyzoites included PtdCho 36:2 (22%), PtdEtn 36:3 and 34:2 (both 23%), PtdThr 40:5 (62%), PtdIns 34:1 (46%), PtdSer 36:3 (17%), and PtdGro 30:0 (45%) (Fig. 1c). On the other hand, C36:2 (18:1/18:1) was the dominant species of most lipid classes in sporozoites, followed by shorter chains between C30 and C34 (Fig. 1c). PtdThr was the only exception with C36:1 (41%) and C36:2 (26%) as its first and second most abundant species (Fig. 1c). Moreover, when compared to other sporozoite phospholipids, PtdThr and PtdSer contained a higher proportion of species with long acyl chains C38–C42 (26% of PtdThr and 20% of PtdSer) and less of species with shorter acyl chains C28–C34 (7% of PtdThr and 3% of PtdSer). Collectively, these results show the presence of notably distinct lipid species in two related parasites, E. falciformis and T. gondii.

Eimeria sporozoites express exclusive phytosphingosine species

The presence of IPC species in Eimeria sporozoites was not anticipated. Therefore, we investigated this lipid class further by high-field orbitrap MS to endorse its existence in Eimeria (Fig. 1d). A query for the accurate masses in the main lipid databases of Lipidbank (lipidbank.jp), LipidMaps (lipidmaps.org), and the Alex123 lipid calculator (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24244551) found only IPC species as candidates with adequate mass accuracy (difference between theoretical and observed mass < 2 ppm). Furthermore, MS/MS analysis of the candidate IPC ions produced m/z 259.011 and m/z 241.022 as the primary fragment ions in the negative ionization mode, corresponding at the ppm-level to inositol phosphate after a loss of H2O (Figure S2A). Not least, the observed retention time of the lipid in question was 10–12 s longer than that of the matching glycerophospholipid class PtdIns (Fig. 1a). This is consistent with the observed retention time shifts for the sphingolipid classes found in Toxoplasma tachyzoites, where the sphingolipids EPC and SM elute 10–12 s after their related glycerophospholipid classes PtdEtn and PtdCho, respectively. Fragmentation of IPC species in positive mode revealed that IPC species contain four hydroxyl groups in the ceramide backbone (indicated by “4” suffix in the peak labeling of Fig. 1d). One of these hydroxyl groups is conjugated to the fatty acid moiety of the molecule as further fragmentation of the ceramide-like ion invariably lost one hydroxyl group together with the loss of the fatty acyl chain (Figure S2B). Likewise, IPC species containing only three hydroxyl groups (labeled “3” in Fig. 1d) in the backbone produced ion with m/z of 300.290. Hence, phytosphingosine was the only detected sphingoid base, and alpha-hydroxylation of the fatty acid was commonly observed in Eimeria sporozoites.

Eimeria sporozoites encode an intricate network for de novo phospholipid biogenesis

Having identified major lipid classes expressed in sporozoites, we next performed a thorough bioinformatics search for the presence of corresponding enzymes in the E. falciformis genome (www.eupathdb.org)23,26. The query sequences included enzymes that have been characterized from various eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms. We could identify a total of 21 enzymes potentially involved in phospholipid synthesis of E. falciformis (Table S1). Some enzymes, PtdGro phosphate phosphatase (PGPP), ethanolamine phosphotransferase (EPT) and PtdEtn methyltransferase (PEMT), could not be found in E. falciformis. We also compared the repertoire of lipid synthesis genes present in E. falciformis with other parasitic protists. Our results showed that three coccidian parasites E. falciformis, T. gondii and Neospora caninum shared similar inventory, which was bigger and more intricate than other apicomplexan (Plasmodium and Cryptosporidium) and kinetoplastid (Trypanosoma and Leishmania) parasites (Table S1). For example, Eimeria, Toxoplasma and Neospora all possess a PtdThr synthase (PTS), which is absent in other parasites. Likewise, many enzymes occur as two or even three distinct isoforms in coccidians, e.g., we detected three paralogs for DAG kinase (DGK) and choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase (CEPT). In addition, we found 2 isoforms for PtdSer decarboxylase (PSD) and each of the enzymes synthesizing PtdOH (glycerol-3P acyltransferase or G3PAT; Lyso-PtdOH acyltransferase or LPAAT) and CDP-DAG (CDP-DAG synthase or CDS).

We were able to clone and experimentally annotate the full-length sequences of 19 enzymes using the RNA isolated from Eimeria sporozoites, which confirmed the transcription of nearly all lipid synthesis genes (Figure S3). The two open reading frames encoding for EfDGK3 and EfCEPT3 could not be amplified from the parasite RNA. Primary structures of the cloned enzymes revealed that all of them harbor intact catalytic domains with conserved residues required for substrate/cofactor binding, as exemplified for PtdSer synthase (PSS) and PTS (Figure S4). Most proteins except for LPAAT2, DGK1/2, PtdGro phosphate synthase (PGPS), cardiolipin synthase (CLS), and PSD1/2 harbor one or more defined transmembrane regions (Figure S3), signifying their membrane-binding nature. Notably, G3PAT1, DGK2, and PSD2 contain a predicted (secretory) signal peptide at their N termini. Equally, the N termini of PGPS, CLS and PSD1 comprise a mitochondrial targeting peptide. Together, the results suggest expression of an almost complete network for de novo synthesis of major phospholipids in Eimeria sporozoites.

Lipid synthesis in E. falciformis is a phylogenetic mosaic of divergent pathways

We performed phylogenetic clustering of selected enzymes of lipid biogenesis in Eimeria to determine their evolutionary origins. Specifically, G3PAT, LPAAT, CDS, PGPS/CLS, PSD, and PSS/PTS were subjected to cladogram analysis with respective orthologs from the major domains of the tree of life (Fig. 2). EfG3PAT1 and EfLPAAT1 segregated with corresponding homologs from other protozoan parasites, whereas EfG3PAT2 and EfLPAAT2 clustered with homologs from algae and plants (Fig. 2a, b). Similar phylogenetic patterns also applied to EfCDS1 and EfCDS2, of which the latter grouped with CDSs from not only algae and plants but also with orthologs from cyanobacteria (Fig. 2c). In the PtdGro and cardiolipin synthesis pathway, two enzymes (EfPGPS and EfCLS) were identified in E. falciformis, both encompassing the classic duplicated phospholipase D-like domains (Figure S3). EfPGPS and EfCLS clustered together with their protozoan homologs, as well as PGPSs from animals/fungi and prokaryotic CLSs, forming the phospholipase-D-type clade (Fig. 2d). The remaining PGPS and CLS sequences belong to the CDP-alcohol-phosphotransferase-type clade. The two PSDs from E. falciformis (EfPSD1 and EfPSD2) also grouped in different clades. EfPSD1 orthologs are conserved across phyla forming a eukaryotic-type-I clade. However, EfPSD2-type proteins could only be detected in closely related coccidian parasites (Fig. 2e). Phylogenetic analysis of EfPSS and EfPTS demonstrated them as being the base-exchange-type enzymes unlike the CDP-DAG-dependent counterparts of PSS present in bacteria and fungi. Again, EfPSS orthologs are present across the domains of life, whereas EfPTS-type proteins were found only in selected coccidian parasites (Fig. 2f). Collectively, these data reveal a surprising occurrence of fairly divergent enzymes in Eimeria, which have likely been repurposed to serve the parasitic lifecycle.

Fig. 2. Enzymes of lipid synthesis in E. falciformis show diverse origins.

Phylogenetic trees depicting the evolutionary relationships of G3PAT1/2 a, LPAAT1/2 b, CDS1/2 c, PGPS/CLS d, PSD1/2 e, and PSS/PTS f enzymes from E. falciformis with respective orthologs from varied organisms representing the major trees of life. Each tree represents the single most parsimonious tree constructed by Neighbor Joining methods. Branch support was estimated by 100 bootstrap replicates. Circles on the branches indicate the bootstrap values for parsimony. Scale bar represents the number of substitutions per amino-acid site. Sequence information including accession numbers and the organism names are described in Table S2

Enzymes of Eimeria lipid synthesis show compartmentalized distribution

Next, we determined subcellular distribution of aforementioned proteins from E. falciformis. A parallel aim was also to establish an initial genetic manipulation system for E. falciformis. We first overexpressed selected enzymes tagged with a C-terminal HA epitope in E. falciformis under the control of Histone 4 (EfHIS4) promoter and matching 3′UTR (Fig. 3a). Transgenic parasites along with non-transfected control sample were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence assays (Fig. 3b). We were able to localize several albeit not all proteins, which exhibited distinct subcellular distributions. Algal-type EfG3PAT2, prokaryotic-type EfCDS2, and EfPIS showed specific punctate signals located within each merozoite enclosed in schizonts. Eukaryotic-type EfCDS1 displayed faint staining inside merozoites, while coccidian-specific EfPSD2 appeared to be outside merozoites but within schizonts.k

Fig. 3. Localization of selected enzymes in E. falciformis merozoites developing within host cells.

a Schematics of the expression cassette used to express a protein of interest in E. falciformis (EfPOI) under the control of EfHIS4 promoter and 3’UTR. b Immunofluorescence images of transgenic merozoites expressing EfG3PAT2-HA, EfCDS2-HA, EfPIS-HA, EfCDS1-HA, and EfPSD2-HA. Plasmid constructs harboring the indicated ORFs were transfected into sporozoites followed by infection of HFF cells, and immunostaining with anti-HA antibody and E. tenella antiserum cross-reactive to E. falciformis (40–42 h post infection). Non-transfected control parasites exhibited no apparent staining with anti-HA antibody. Scale bars: 2 μm

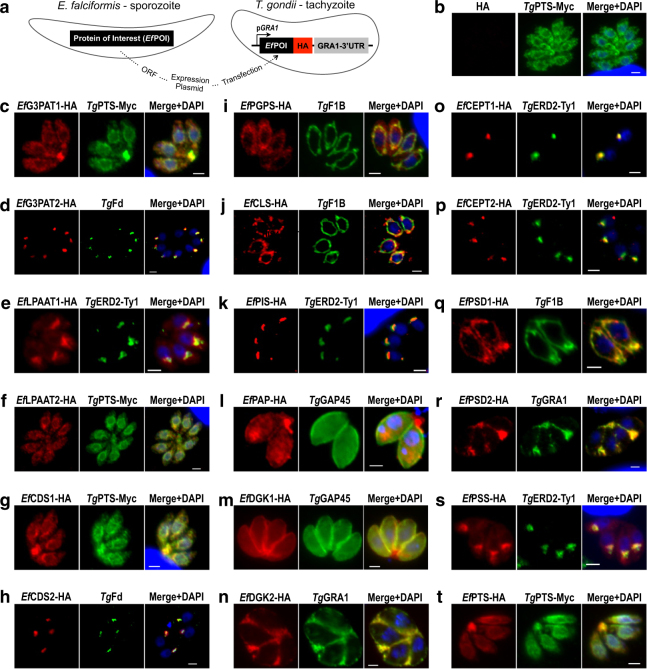

The lack of appropriate organelle markers and sustained in vitro culture of E. falciformis prevented us from interpreting localization results. We therefore performed ectopic overexpression of selected enzymes in tachyzoites of T. gondii. Transgenic tachyzoites expressing Eimeria enzymes with a C-terminal HA tag were co-localized with different organelle markers (Fig. 4a). Tachyzoites expressing TgPTS-Myc only were included as a control (Fig. 4b), which showed no background HA signal. Among transfected samples, EfG3PAT1-HA and EfCDS1-HA were targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; Fig. 4c, g), whereas EfG3PAT2 and EfCDS2 were found in the apicoplast (Fig. 4d, h), which corresponds with the phylogenetic origin of both isoforms and the evolutionary trace of this organelle. EfLPAAT1-HA was expressed primarily in the Golgi complex with a faint staining in the ER (Fig. 4e). Surprisingly, EfLPAAT2 was located mainly in the ER notwithstanding its algal origin (Fig. 4f), indicating an incomplete apicoplast pathway and potential transport of lyso-PtdOH and PtdOH between ER/Golgi and apicoplast. Enzymes of the PtdGro and cardiolipin pathway, EfPGPS and EfCLS, were expressed in the mitochondrion (Fig. 4i, j), whilst the PtdIns synthase (EfPIS) was localized in the Golgi complex (Fig. 4k). The results suggest a transfer of CDP-DAG from the apicoplast/ER to the mitochondrion for the syntheses of PtdGro and cardiolipin, and to the Golgi network for the synthesis of PtdIns.

Fig. 4. Ectopic expression of Eimeria enzymes in Toxoplasma tachyzoites reveals a compartmentalized distribution of lipid biogenesis.

a Scheme showing expression of E. falciformis ORFs into tachyzoites of T. gondii under the control of TgGRA1 promoter and 3’UTR. b Tachyzoites expressing TgPTS-Myc only showing the absence of HA signal (a representative control). c–t Immunofluorescence images of the transgenic tachyzoites expressing EfG3PAT1/2-HA, EfLPAAT1/2-HA, EfCDS1/2-HA, EfPGPS-HA, EfCLS-HA, EfPIS-HA, EfPAP-HA, EfDGK1/2-HA, EfCEPT1/2-HA, EfPSD1/2-HA, EfPSS-HA, and EfPTS-HA. Constructs harboring indicated ORFs were transfected into tachyzoites followed by staining with anti-HA and Alexa594 antibodies (20–24 h post infection). Subcellular localization of each enzyme was confirmed by co-localization with respective organelle markers, including TgPTS-Myc for ER, TgFd for apicoplast, TgERD2-Ty1 for Golgi, TgF1B for mitochondrion, TgGAP45 for the parasite periphery, and TgGRA1 for the parasitophorous vacuole. Scale bars: 2 μm. Images shown are representative of at least three independent transfections. Note that the localization of certain enzymes might be subject to artifact due to ectopic overexpression in T. gondii. A schematized model showing subcellular distribution of all indicated enzymes can be seen in Fig. 7

In eukaryotes, PtdOH is not only used for CDP-DAG production, but also for the synthesis of DAG, which is regulated by two reactions catalyzed by PtdOH phosphatase (PAP) and DGK (Figure S1). EfPAP-HA displayed punctate intracellular distribution in cytomembranes (Fig. 4l), while EfDGK1-HA localized in the parasite periphery (Fig. 4m) and EfDGK2-HA was secreted into the PV (Fig. 4n). DAG serves as a co-substrate for CEPT to synthesize PtdCho and PtdEtn via the Kennedy pathways (Figure S1). Unexpectedly, EfCEPT1 and EfCEPT2 were expressed in the Golgi complex (Fig. 4o, p). PtdEtn can also be generated by decarboxylation of PtdSer (Figure S1). EfPSD1 and EfPSD2 were targeted to the mitochondrion and PV, respectively (Fig. 4q, r). Consistent with localization results, all isoforms residing in the mitochondrion (EfPGPS, EfCLS, and EfPSD1) and PV (EfDGK2 and EfPSD2) harbored targeting motifs at the N termini (mitochondrial or secretory; Figure S3). PtdEtn and/or PtdCho are used to produce PtdSer and PtdThr via base-exchange reactions catalyzed by PSS and PTS, respectively, both of which were detected in the parasite ER with a strong signal of EfPSS in the Golgi network (Fig. 4s, t). Taken together, our localization studies demonstrate an assorted subcellular expression of Eimeria enzymes in merozoites of E. falciformis as well as in tachyzoites of T. gondii.

Trans-genera expression of EfPTS rescues the lytic cycle of the Δtgpts mutant

Next, we tested the functionality of EfPTS, a novel coccidian-specific enzyme, in a mutant of T. gondii lacking PTS expression. Our recent work has shown that the disruption of the PTS catalytic residues in tachyzoites (Fig. 5a—Step 1 and Figure S4) ablates the synthesis of PtdThr, which in turn compromises the calcium-dependent gliding motility, invasion and egress, leading to impairment of the lytic cycle7,20,21. The Δtgpts mutant therefore not only offered a tool to test the catalytic function of EfPTS, but also allowed us to assess the physiological significance of specific PtdThr species in tachyzoites (see below). The EfPTS protein governed by pGRA1 elements was expressed at the uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRT) locus in the Δtgpts mutant (Fig. 5a—Step 2). The eventual complemented strain (Δtgpts/EfPTS) was subjected to phenotypic assays to elucidate the biological impact of EfPTS expression. The Δtgpts mutant formed significantly smaller (−73%) and fewer (−69%) plaques compared to the parental strain in plaque assay, confirming the earlier work7. Quite notably, EfPTS completely restored the lytic cycle of the PTS mutant (Fig. 5b-d). In-depth phenotyping of the Δtgpts strain revealed an evident impairment in its invasion, egress and motility, but not in replication (Fig. 5e-j). The parasite invasion, egress and gliding motility were reinstated in the complemented strain. Remarkably, ectopic expression of EfPTS also promoted intracellular proliferation of the mutant (Fig. 5f). These assays confirm that EfPTS can compensate for the loss of its counterpart in tachyzoites.

Fig. 5. EfPTS can complement all phenotypic defects in the PTS mutant of T. gondii.

a Schematics illustrating a targeted disruption of the TgPTS gene (Step 1), and subsequent insertion of EfPTS expression cassette at the TgUPRT locus by negative selection (Step 2). The Δtgpts mutant was created by Arroyo-Olarte RD et al., and found defective in invasion, egress and motility, but not in replication7. The complemented (Δtgpts/EfPTS) strain was made by expressing EfPTS in the Δtgpts mutant under the control of TgGRA1 elements. b–d Plaque assays showing the phenotypic complementation of the Δtgpts mutant by EfPTS. The indicated strains were examined for their ability to recapitulate successive lytic cycles in HFF cells by plaque sizes (c) and numbers (d). 90 plaques of each strain were measured using the ImageJ suite. e–g Invasion, replication, and egress assays using the parental, Δtgpts and Δtgpts/EfPTS strains. Invasion rates of 1500–2500 parasites of each strain are presented. A total of 200–350 vacuoles were numerated for the number of replicating parasites (f) or for natural egress (g). h Images demonstrating the gliding motility trails of specified strains, as visualized by immunostaining of TgSAG1 protein. Scale bar: 10 μm. 100–120 parasites of each strain were scored for the motile fraction (i) and trail length (j). Numerical values in all graphs show the means with SEM from three independent assays (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). COS, crossover sequence; E.C., expression cassette; a.u., arbitrary unit

EfPTS can restore the loss of tachyzoite-specific PtdThr species in the Δtgpts mutant

As mentioned above, the composition of PtdThr species were notably different between E. falciformis sporozoites and T. gondii tachyzoites (Fig. 1c). The most common PtdThr species in sporozoites was C36:1 (41%), followed by C36:2 (26%), C38:4 (10%), C34:1 (7%), C40:6 (6%), and C38:2 (6%) (Fig. 1c, 6a). In tachyzoites, however, all detected PtdThr species contained polyunsaturated fatty acid chains, including C40:5 (62%), 38:4 (12%), 36:4 (11%), 40:6 (10%), and 38:5 (4%) (Fig. 1c, 6b). The MS/MS analysis identified 18:0/18:1 and 20:1/20:4 as the most prevalent PtdThr species in Eimeria sporozoites and in the parental tachyzoites of T. gondii, respectively (Fig. 6c, d). As expected, lipidomic analysis of the Δtgpts strain confirmed the lack of all PtdThr species (Fig. 6e). Surprisingly, complementation of the PTS mutant with EfPTS fully restored the PtdThr content with the same species as present in the parental tachyzoites, but not with those expressed in Eimeria sporozoites. Interestingly, EfPTS does not produce detectable amounts of 18:0/18:1 PtdThr in tachyzoites even though these fatty acids are readily available (Fig. 1c), suggesting a specific need of PtdThr containing polyunsaturated acyl chains (mainly 20:1/20:4) for the lytic cycle of T. gondii. Besides, because the potential donor species of PtdCho and PtdEtn with 20:1/20:4 are not detectable in T. gondii, synthesis of such PtdThr species is likely to occur predominantly by acyl chain remodeling of lipids.

Fig. 6. EfPTS can produce tachyzoite-specific PtdThr species in the PTS knockout strain of T. gondii.

a, b MS analysis of PtdThr isolated from the sporozoites of E. falciformis or from the tachyzoites of T. gondii. Lipid species were identified by their product spectra in the negative ionization mode. Note that the dominant PtdThr species in Eimeria harbor C36:1/C36:2 acyl chains in contrast to C40:5 in Toxoplasma. c, d MS/MS spectra of the major PtdThr peaks (m/z 802.6 for E. falciformis and m/z 850.6 for T. gondii). Acyl chains were identified as 18:0/18:1 (C36:1) and 20:1/20:4 (C40:5). e MS analysis of lipids isolated from the parental, Δtgpts and Δtgpts/EfPTS strains of T. gondii. The data show a major (40:5) and several minor (40:6, 38:4, 38:5, and 36:4) PtdThr species in the parental strain, which are all absent in the Δtgpts mutant. The loss of all indicated lipid species is restored by expression of EfPTS in the Δtgpts/EfPTS strain

Sphingolipid synthase from E. falciformis is a plant-like protein located in the Golgi/ER network

Finally, we focused on characterizing yet-another enzyme underlying the synthesis of an exclusive lipid in E. falciformis, namely plant-like sphingolipids. Phylogenetic analysis revealed a distinct clade of sphingolipid synthase (SLS) from E falciformis along with homologs from arabidopsis and apicomplexan parasites (Figure S5A). SLS from kinetoplastid parasites, SM \synthase (SMS) from humans/animals, as well as IPC synthase (IPCS) from red algae and fungi formed their own individual clusters. Immunolocalization of C-terminally HA-tagged EfSLS in tachyzoites of T. gondii exhibited a weak perinuclear staining (apparently in the ER) along with a notably strong signal at the anterior end of nucleus corresponding to the Golgi network (Figure S5B). Indeed, TgERD2, a known marker of the Golgi complex, co-localized with EfSLS. We next performed functional complementation of a previously reported conditional yeast mutant, in which the promoter of endogenous IPC synthase has been replaced by a galactose-inducible element27. Consequently, the strain grows only in the presence of galactose but not glucose. As expected, the growth of the mutant under non-permissive condition could be restored by the ScIPCS (aka ScAUR1), but not by the empty vector (Figure S5C). TgSLS also rescued the growth of the strain in glucose medium, confirming the expression of a catalytically competent enzyme. EfSLS, however, failed to amend the growth defect under non-permissive condition, which may be due to functional divergence of lipid classes made by EfSLS when compared to ScIPCS and TgSLS.

Discussion

This study examined the phospholipid composition and the enzymatic network of lipid biogenesis in sporozoites of E. falciformis, which express all common eukaryotic glycerophospholipids, such as PtdCho, PtdEtn, PtdIns, PtdSer, and PtdGro (Fig. 7). The relative proportion of these lipids is similar to what has been described in various lifecycle stages of other protozoan parasites, including T. gondii25,28, Plasmodium falciparum8,29–31, Trypanosoma brucei32,33, Trypanosoma cruzi34,35, and Leishmania donovani36,37. Lipid species profiles in Eimeria sporozoites are quite noteworthy however; for instance, glycerophospholipids are composed of primarily saturated and monounsaturated fatty acid chains that are in most species not longer than C18. Among them, the most abundant acyl chains are C18:0 and C18:1, which form C36:1 (18:0/18:1) and C36:2 (18:1/18:1) as the dominant species for most glycerophospholipids. In addition, we show the natural occurrence of PtdThr in Eimeria sporozoites. PTS could only be found in the coccidian parasites (E. falciformis, T. gondii, N caninum), suggesting the evolution of PtdThr to enable a specialized function that could not be satisfied by generic phospholipids. Accordingly, expression of EfPTS in the PTS mutant of T gondii produces PtdThr species with tachyzoite-specific fatty acids (mainly 20:1/20:4). The occurrence of distinct lipid species therefore appears to be critical for the development of individual stages.

Fig. 7. Compartmentalized network of phospholipid synthesis and underlying inter-organelle trafficking in E. falciformis sporozoites.

The illustration reveals the pathways that have been identified based on expression and localizations of the enzymes in this study. Shown on the upper right corner is a sporulated oocyst enclosing four sporocysts, each with two sporozoites. Pathways located in individual organelles are zoomed in. The gray bars between indicated organelles show possible inter-organelle trafficking of phospholipids and precursors. The prokaryotic-type (EfCDS2 and EfCLS), algal-type (EfG3PAT2 and EfLPAAT2), plant-type (EfSLS), and coccidian-specific (EfPTS and EfPSD2) enzymes are in red, blue, green, and purple backgrounds, respectively. Note that EfLPAAT1 and EfPSS also reveal a weak ER signal in addition to the dominant Golgi localization, as shown in Fig. 4

Sphingophospholipids are another major class of lipids in eukaryotic cells. The main sphingophospholipid in fungi and plants is IPC38–40, while SM and EPC are present in mammals41. T. gondii tachyzoites also possess EPC and SM, confirming an earlier study25. Previous work in T. brucei have revealed the presence of IPC and SM in the procyclic stage of the parasite, as well as SM and EPC in the bloodstream stage42, indicating a highly stage-specific biogenesis of sphingophospholipids in this parasite. Here, we identified IPC as the prime sphingophospholipid in E. falciformis sporozoites, whose sphingoid backbone consisted exclusively of phytosphingosine (t18:0). In contrast, mammalian cells contain sphingosine (d18:1)-based backbones. This suggests that Eimeria is indeed capable of synthesizing the complete IPC lipid class de novo. Since IPC synthesis has no equivalent in mammalian cells, SLS enzymes with IPC synthase activity are considered as potential drug targets to treat protozoan infection27,43,44.

In Toxoplasma and Plasmodium, short saturated acyl chains (C14:0, C16:0) are produced through the prokaryotic-type (type II) fatty acid synthase pathway in the apicoplast45,46. These acyl chains are then exported to the ER, where they are modified by fatty acid elongase pathway to generate longer saturated and unsaturated fatty acids45. They are coutilized with Glycerol-3P to produce Lyso-PtdOH and PtdOH by sequential catalytic actions of G3PAT and LPAAT. PtdOH is then utilized by CDS and PAP to synthesize CDP-DAG and DAG, respectively. We found a fungal-type EfG3PAT1 in the ER and an algal-type EfG3PAT2 in the apicoplast (Fig. 7), which is consistent with recent reports on localizations of their homologs in Toxoplasma and Plasmodium16,18,19,47. Besides, E. falciformis expresses two paralogs of LPAAT and CDS. The eukaryotic-type LPAAT and CDS including EfLPAAT1 and EfCDS1, exist in the ER or ER/Golgi complex in all examined parasitic protists16,48–51. Homologs of algal-type EfLPAAT2 and prokaryotic-type EfCDS2 occur only in coccidians, which implies a loss of these two enzymes during the evolution of other parasites (Table S1). EfCDS2 is likely localized in the apicoplast, compatible with our recent report on the localization of its homolog in Toxoplasma51. However, EfLPAAT2 exhibits an intriguing presence in the ER. These results suggest that the ER/Golgi complex cooperates with the apicoplast for the biogenesis of PtdOH and CDP-DAG.

Among downstream pathways, we identified EfPIS and final enzymes of PtdCho and PtdEtn synthesis, EfCEPT1 and EfCEPT2. All these enzymes belong to the CDP-alcohol phosphotransferase family (Figure S3) and were located in the Golgi complex. CEPT is previously reported in the ER of T. brucei52, while PIS is localized in both ER and Golgi complex53. The expression of CEPT and PIS pathways in Golgi endows this organelle a significant role in lipid biogenesis of E. falciformis. PtdEtn synthesis by decarboxylating PtdSer through the catalytic action of PSD1 and PSD2 occurs in the mitochondrion and PV, respectively. Subcellular localizations of the two EfPSD isoforms correspond to their homologs in T. gondii54,55, but different from PfPSD residing in the ER56. Unlike kinetoplastids, where Kennedy pathways are the main source of PtdEtn52,57, PSD activity appears to play a major role in PtdEtn biogenesis in T. gondii3,54,55. The mitochondrion also harbors EfPGPS and EfCLS for the synthesis of PtdGro and cardiolipin that is similar to T. brucei where PGPS and CLS form a large complex in the inner mitochondrial membrane58,59. On the other hand, EfPTS and EfPSS are found in the ER/Golgi, which resembles the tachyzoites of T. gondii7. Most enzymes are likely to be essential for the sporozoite formation because unlike other infectious stages, this stage does not have access to host-derived metabolites. Physiological assessment of these proteins shall await the development of appropriate gene manipulation tools and in vitro culture for E. falciformis. Likewise, isotope labeling of sporulating oocysts will facilitate further research on de novo synthesis and functional evaluation of the eventual mutants.

Collectively, our study reveals a highly interweaved and compartmentalized network of lipid synthesis with varied phylogenetic origins and notable exceptions in E. falciformis sporozoites (Fig. 7). Such a complex network is expected to require a significant inter-organelle trafficking of lipids and their precursors. Multiple membrane contact sites have been reported between ER/Golgi complex, apicoplast and mitochondrion in apicomplexan parasites60–62, though it remains to be seen whether they serve as privileged zones of lipid exchange. Last but not least, this work rationalizes the evolutionary retention of an entire metabolic module in a model parasite that is meant to facilitate the development of free-living stage during the natural lifecycle.

Materials and methods

Biological reagents and resources

Oocysts of E. falciformis were obtained from Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany). The RHΔku80-Δhxgprt strain of T. gondii63 was kindly provided by Vern Carruthers (University of Michigan, MI). The Δtgpts mutant7,20 was generated by Ruben D. Arroyo-Olarte (Humboldt University Berlin, Germany). The human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cells and NMRI mice were purchased from Cell Lines Service (Eppelheim, Germany) and Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), respectively. The yeast IPCS mutant (YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1) and corresponding expression vector (pRS426-MET25) were provided by Ralph T. Schwarz (University of Marburg, Germany). Primary antibodies recognizing the TgF1B, TgFd, TgGAP45, TgGRA1, and TgSAG1 proteins were provided by Peter Bradley (University of California, CA), Frank Seeber (Robert Koch Institute Berlin, Germany), Dominique Soldati-Favre (University of Geneva, Switzerland), Marie-France Cesbron-Delauw (University Joseph Fourier, France), and Jean-Francois Dubremetz (University of Montpellier, France), respectively. The antiserum recognizing Eimeria tenella (cross-reactive to E. falciformis) was donated by Fiona Tomley (Royal Veterinary College, UK). Antibodies against the HA, Myc and Ty1 epitopes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Secondary antibodies (Alexa488 and Alexa594) and oligonucleotides were procured from Life Technologies (Germany). The organelle markers in this study included TgPTS-Myc for ER7, TgFd for apicoplast64, TgERD2-Ty1 for Golgi complex65, TgF1B for mitochondrion55, TgGAP45 for parasite periphery66, and TgGRA1 for PV67.

Propagation of E. falciformis and isolation of sporozoites

The lifecycle of E. falciformis was maintained by continuous passage of the parasite oocysts in NMRI mice as described elsewhere22. Oocysts in the animal feces were washed in water, floated with NaOCl, and stored in potassium dichromate at 4 °C up to 3 months68. The isolation of E. falciformis sporozoites was performed as described before24. In brief, purified oocysts were digested with 0.4% pepsin (pH 3, 37 °C, 1 h) before washing with PBS. Sporocysts were released by mixing oocysts with glass beads (0.5 mm) and vortexing in DMEM supplemented with 0.25% trypsin, 0.75% sodium tauroglycocholate, 20 mM glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin for 2 min at 37 °C. Free sporozoites were purified by DE-52 anion exchange chromatography69, and directly used for transfection or stored at −80 °C for lipidomic analysis, as stated below.

Study approval

The propagation of E. falciformis in mouse was performed according to the German Animal Welfare Act (Tierschutzgesetz), as dictated by the overseeing authority Landesamt fuer Gesundheit und Soziales, Berlin, Germany (LAGeSo authorization # IC 113 – H 0098/04).

In vitro culture of T. gondii

Tachyzoites of T. gondii were propagated by serial passage in HFF monolayers at a MOI of 3. HFFs were cultured in DMEM containing fetal calf serum (10%, PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany), glutamine (2 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml) and MEM non-essential amino acids in a humidified incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C). Cells were harvested by trypsinization and grown to confluence in flasks, dishes or plates, as needed. For experiments, parasites were mechanically released from late-stage cultures and used immediately. Briefly, parasitized cells (40–42 h post infection) were scraped in fresh medium and squirted through 23 G and 27 G syringes (2× each) to obtain extracellular tachyzoites, which were either used directly for transfection and phenotyping assays, or stored at −80 °C for lipidomic analysis, as described below.

Lipid analysis

Pellets of freshly frozen (metabolically quenched) purified sporozoites (E. falciformis) and tachyzoites (T. gondii) were suspended in 0.8 ml PBS (3 × 107 parasites) and subjected to lipid extraction according to Bligh and Dyer70. Total lipids were dried under nitrogen stream and dissolved in 1 ml chloroform and methanol mixture (1:1), of which a 10 μl aliquot was introduced onto a Kinetex HILIC column (dimensions 50×4.6 mm, 2.6 μm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Phospholipid (sub-)classes were resolved at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, as described earlier71. The column effluent was introduced into a LTQ-XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and analyzed by electrospray ionization in positive and negative ionization modes. Commercial standards were used to calibrate and quantify the recovery of lipids. Acyl chain composition of individual lipids was determined by data-dependent MS/MS in separate runs. To confirm lipid class, acyl chain composition and elemental composition of the identified lipids, a subset of samples was run on a Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), operated at an orbitrap resolution of 120.000 and generating 30 data-dependent MS/MS spectra per second in the linear ion trap. For IPC structure studies, product ions were routed from the ion routing multipole to the orbitrap mass analyzer. Mass errors between observed lipid ions and theoretical m/z values were <2 ppm for orbitrap studies. Glycerophospholipids species were all from the diacyl subclass. We did not detect any ether-lipids. The procedure did not result in any noticeable lipid oxidation. The use of LCMS allowed us to discriminate two isobaric lipids of different classes (such as PtdEtn 36:2 and PtdCho 33:2), which were chromatographically fully separated. Data were processed using the most recent version of package “XCMS” under R (https://www.R-project.org)72. The lipid abbreviations herein follow the IUPAC-IUB nomenclature (http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/lipid/).

Bioinformatics and phylogeny studies

Enzymes of phospholipid biogenesis in protozoan parasites were identified using EuPathDB (www.eupathdb.org) and ToxoDB (www.toxodb.org)26,73. All sequences reported in this study were experimentally annotated. The functional domains and transmembrane regions were predicted using the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) and Transmembrane Hidden Markov Model (TMHMM) (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/), respectively. The secretory signal or mitochondrial targeting peptide was examined using SignalP v4.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) and MitoProt (https://ihg.gsf.de/ihg/mitoprot.html) algorithms. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by CLC Sequence Viewer v7.7 (http://www.clcbio.com/products/clc-sequence-viewer/) and visualized with FigTree v1.4.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) softwares. The sequence accession numbers with respective organism names are described in Table S2.

Molecular cloning and making of transgenic parasites

RNA was isolated from freshly purified sporozoites of E. falciformis using TRIzol-extraction method and subsequently reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA (Life Technologies, Germany). The genomic DNA was isolated using the genomic DNA preparation kit (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany). All amplicons were amplified using Pfu Ultra II fusion HS polymerase (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and specific primers (Table S3). For ectopic overexpression of selected proteins in E. falciformis, the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of EfHIS4 and the ORF of EfPIS were cloned into the pTKO-DHFR-TS plasmid by overlap extension PCR. The ORFs of other enzymes were cloned into the same vector by replacing EfPIS ORF using AvrII/PacI restriction sites. For ectopic overexpression of selected proteins in T. gondii tachyzoites, ORFs of E. falciformis sporozoites were cloned into the pGRA1-UPKO plasmid using NsiI/PacI restriction sites. The eventual constructs were transformed into E. coli XL-1b strain for cloning and vector amplification.

The constructs were transfected into freshly released T. gondii tachyzoites of the RHΔku80-Δhxgprt strain (50 μg DNA, ~107 parasites) or E. falciformis sporozoites (50 μg DNA, 2 × 106 parasites) suspended in filter-sterile cytomix (120 mM KCl, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 10 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glutathione, 5 mM ATP, pH 7.6) using a BTX electroporation instrument (2 kV, 50 Ω, 25 μF, 250 μs). Tachyzoites expressing ER-localized (EfG3PAT1, EfLPAAT2, EfCDS1, EfPTS) and Golgi-localized (EfLPAAT1, EfPSS, EfCEPT1, EfCEPT2, EfPIS) proteins were co-transfected with constructs encoding for TgPTS-Myc and TgERD2-Ty1, respectively, for co-localization studies. Transfected parasites were used to infect HFFs for indirect immunofluorescence assays (see below), and screened for transient expression of E. falciformis enzymes. The Δtgpts/EfPTS strain was generated by transforming the pGRA1-UPKO-EfPTS construct into the Δtgpts strain followed by negative selection for the disruption of the TgUPRT locus using 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (5 μM)74.The drug-resistant parasites were cloned by limiting dilution and screened by PCR for the expression of EfPTS. Positive clones were subjected to the lytic cycle assays and lipidomic analysis, as described elsewhere.

Indirect immunofluorescence assays

Parasitized HFFs cultured on glass coverslips were washed with PBS 20–24 h (tachyzoites) or 40–42 h (sporozoites) post infection, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and neutralized with 0.1 M glycine in PBS for 5 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.2% triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min and treated with 2% bovine serum albumin in 0.2% triton X-100 and PBS for 20 min. Samples were stained with a combination of primary antibodies (anti-HA, 1:3000; anti-Myc, 1:3000; anti-Ty1, 1:50; anti-TgFd, 1:500; anti-TgF1B, 1:1000; anti-TgGRA1, 1:500; anti-TgGAP45, 1:3000; anti-TgSAG1, 1:1500; antiserum recognizing E. tenella, 1:2000) for 1 h, as shown in figures. Cells were washed three times with 0.2% triton X-100 in PBS and then stained with Alexa488/594-conjugated antibodies for 45 min. Following three additional washings with PBS, samples were mounted in fluoromount G / DAPI mixture (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), and then stored at 4 °C. Imaging was done by a fluorescence microscope (ApoTome, Zeiss, Germany).

Lytic cycle assays

Plaque assays were performed by infecting HFF monolayers grown to confluence in 6-well plates (250 tachyzoites/well). Infected cultures were incubated unperturbed for 7 days and samples were fixed with ice-cold methanol followed by staining with crystal violet dye. Plaques were imaged and scored for sizes and numbers using the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). To test the invasion efficiency, tachyzoites of each strain were used to infect confluent HFFs (MOI, 10) for 1 h. Noninvasive parasites were stained with anti-TgSAG1 antibody prior to detergent permeabilization. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS, permeabilized with 0.2% triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min and then stained with anti-TgGAP45 antibody to visualize intracellular parasites. The percentages of invaded parasites were determined to compare the invasion efficiency of different strains. For replication and egress assays, confluent HFFs cultured on coverslips in 24-well plates were infected with tachyzoites of each strain (MOI, 1), fixed at indicated time points (40 h for replication; 48 and 72 h for egress) and then subjected to immunostaining using anti-TgGAP45 antibody, as described above. The mean percentage of vacuoles containing variable numbers of intracellular parasites was scored to examine the replication phenotype. Egress was calculated by comparing the vacuole numbers between 48 h (intracellular) and 72 h (egressing). For motility assays, fresh syringe-released parasites were incubated on BSA (0.01%)-coated coverslips in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (15 min, 37 °C), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.05% glutaraldehyde (10 min), and then stained with anti-TgSAG1 and Alexa488 antibodies. Motile fractions and trail lengths were quantified using ImageJ software.

Functional complementation of yeast

Yeast cells (YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1) were grown in synthetic histidine-free minimal medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base; Difco) supplemented with appropriate amino acids, 4% galactose and 2% raffinose (SGR medium). The mutant was transformed with the constructs expressing EfSLS, TgSLS, ScIPCS, or the empty vector (pRS426-MET25). The cDNAs of EfSLS and TgSLS were amplified from the total RNA isolated from Eimeria sporozoites and Toxoplasma tachyzoites, respectively. ScIPCS ORF was cloned from yeast gDNA (primers in Table S3). The ORFs were ligated at the SpeI and HindIII into pRS426-MET25 vector expressing the URA3 gene for selecting yeast transformants in uracil-deficient medium. The plasmid allowed the expression of a protein of interest under the control of the MET25 promoter of S. cerevisiae. Transformation was performed using standard yeast protocols. Transgenic cells were grown in uracil- and histidine-dropout SGR medium at 30 °C, and positive clones were identified by PCR and sequencing. For complementation assays, yeast cells were grown in liquid medium to an A600 of ∼0.1, and serial dilutions (1:5) were spotted on synthetic uracil- and histidine-dropout plates containing either 4% galactose and 2% raffinose (synthetic galactose-raffinose or SGR medium), or 2% glucose (synthetic dextrose or SD medium). Plates were incubated for 3–4 days at 30 °C.

Statistics

All data are shown as the mean with SEM from three or six independent assays, as indicated in figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism program. Significance was tested by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test with equal variances (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Data deposition

Sequences of Eimeria falciformis proteins reported in this study have been deposited to GenBank. EfG3PAT1, KX785365; EfG3PAT2, KX785366; EfLPAAT1, KX785367; EfLPAAT2, KX785368; EfCDS1, KX017547; EfCDS2, KX017548; EfPAP, KX785369; EfDGK1, KX785370; EfDGK2, KX785371; EfDGK3, KX785372; EfPGPS, KX7853713; EfCLS, KX785374; EfPIS, KX785375; EfCEPT1, KX785376; EfCEPT2, KX785377; EfCEPT3, KX785378; EfPSD1, KX785379; EfPSD2, KX785380; EfPSS, KX785381; EfPTS, KX785382; EfSLS, MF577034.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Grit meusel, Manuel Rauch, Stefanie Brandt, Janina Zeqiraj and Laura Thurow (Humboldt University, Berlin) for technical assistance, and Jeroen W.A. Jansen (Utrecht University) for aiding lipidomic studies. This work was funded by two research grants (GRK2046, GU1100/4-1) and a Heisenberg program award (GU1100/8-1) to N.G., as well as by a research grant to M.J.L. (LE2846/2-1), all of which were awarded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Authors' contributions

N.G. and P.K. conceived the study and designed experiments. P.K. performed the experiments. J.F.B. and J.B.H. helped with lipidomics. P.K., N.G., and J.F.B. analyzed results. M.J.L., J.B.H., and N.G. contributed reagents/tools. P.K. and N.G. wrote the paper. All authors approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper at (10.1038/s41421-018-0023-4).

References

- 1.Adl SM, et al. Diversity, nomenclature, and taxonomy of protists. Syst. Biol. 2007;56:684–689. doi: 10.1080/10635150701494127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowper B, Matthews S, Tomley F. The molecular basis for the distinct host and tissue tropisms of coccidian parasites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2012;186:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta N, Zahn MM, Coppens I, Joiner KA, Voelker DR. Selective disruption of phosphatidylcholine metabolism of the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii arrests its growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:16345–16353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dechamps S, et al. The Kennedy phospholipid biosynthesis pathways are refractory to genetic disruption in Plasmodium berghei and therefore appear essential in blood stages. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2010;173:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobenchik AM, et al. Plasmodium falciparum phosphoethanolamine methyltransferase is essential for malaria transmission. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:18262–18267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313965110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sen P, Vial HJ, Radulescu O. Kinetic modelling of phospholipid synthesis in Plasmodium knowlesi unravels crucial steps and relative importance of multiple pathways. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013;7:123. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arroyo-Olarte RD, et al. Phosphatidylthreonine and lipid-mediated control of parasite virulence. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulati S, et al. Profiling the essential nature of lipid metabolism in asexual blood and gametocyte stages of Plasmodium falciparum. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18:371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nitzsche, R., Zagoriy, V., Lucius, R. & Gupta, N. Metabolic cooperation of glucose and glutamine is essential for the lytic cycle of obligate intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 126-141 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Charron AJ, Sibley LD. Host cells: mobilizable lipid resources for the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3049–3059. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coppens I. Contribution of host lipids to Toxoplasma pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caffaro CE, Boothroyd JC. Evidence for host cells as the major contributor of lipids in the intravacuolar network of Toxoplasma-infected cells. Eukaryot. Cell. 2011;10:1095–1099. doi: 10.1128/EC.00002-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Athenstaedt K, Daum G. Phosphatidic acid, a key intermediate in lipid metabolism. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;266:1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vance JE, Tasseva G. Formation and function of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys. Acta. 2013;1831:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazumdar J, E HW, Masek K, C AH, Striepen B. Apicoplast fatty acid synthesis is essential for organelle biogenesis and parasite survival in Toxoplasma gondii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13192–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603391103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindner SE, et al. Enzymes involved in plastid-targeted phosphatidic acid synthesis are essential for Plasmodium yoelii liver-stage development. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;91:679–693. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Schaijk BC, et al. Type II fatty acid biosynthesis is essential for Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite development in the midgut of Anopheles mosquitoes. Eukaryot. Cell. 2014;13:550–559. doi: 10.1128/EC.00264-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amiar S, et al. Apicoplast-localized lysophosphatidic acid precursor assembly is required for bulk phospholipid synthesis in Toxoplasma gondii and relies on an algal/plant-like glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005765. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shears MJ, et al. Characterization of the Plasmodium falciparum and P. berghei glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase involved in FASII fatty acid utilization in the malaria parasite apicoplast. Cell Microbiol. 2017;19:e12633. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuchipudi, A., Arroyo-Olarte, R. D., Hoffmann, F., Brinkmann, V. & Gupta, N. Optogenetic monitoring identifies phosphatidylthreonine-regulated calcium homeostasis in Toxoplasma gondii. Microbial Cell3 (5), 215-223 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Arroyo-Olarte, R. D. & Gupta, N. Phosphatidylthreonine: An exclusive phospholipid regulating calcium homeostasis and virulence in a parasitic protest. Microbial Cell3 (5), 215-223 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Schmid M, Lehmann MJ, Lucius R, Gupta N. Apicomplexan parasite, Eimeria falciformis, co-opts host tryptophan catabolism for life cycle progression in mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20197–20207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.351999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heitlinger E, Spork S, Lucius R, Dieterich C. The genome of Eimeria falciformis--reduction and specialization in a single host apicomplexan parasite. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:696. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmid M, et al. Eimeria falciformis infection of the mouse caecum identifies opposing roles of IFNgamma-regulated host pathways for the parasite development. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:969–982. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welti R, et al. Lipidomic analysis of Toxoplasma gondii reveals unusual polar lipids. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13882–13890. doi: 10.1021/bi7011993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aurrecoechea C, et al. EuPathDB: a portal to eukaryotic pathogen databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D415–D419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denny PW, Shams-Eldin H, Price HP, Smith DF, Schwarz RT. The protozoan inositol phosphorylceramide synthase: a novel drug target that defines a new class of sphingolipid synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:28200–28209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600796200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foussard F, Gallois Y, Girault A, Menez JF. Lipids and fatty acids of tachyzoites and purified pellicles of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Res. 1991;77:475–477. doi: 10.1007/BF00928412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsiao LL, Howard RJ, Aikawa M, Taraschi TF. Modification of host cell membrane lipid composition by the intra-erythrocytic human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem J. 1991;274:121–132. doi: 10.1042/bj2740121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dechamps S, Shastri S, Wengelnik K, Vial HJ. Glycerophospholipid acquisition in Plasmodium - a puzzling assembly of biosynthetic pathways. Int J. Parasitol. 2010;40:1347–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran PN, et al. Changes in lipid composition during sexual development of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Malar. J. 2016;15:73. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1130-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll M, McCrorie P. Lipid composition of bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Comp. Biochem Physiol. B. 1986;83:647–651. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(86)90312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patnaik PK, et al. Molecular species analysis of phospholipids from Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms. Mol. Biochem Parasitol. 1993;58:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90094-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveira MM, Timm SL, Costa SC. Lipid composition of Trypanosoma cruzi. Comp. Biochem Physiol. B. 1977;58:195–199. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(77)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaneda Y, Nagakura K, Goutsu T. Lipid composition of three morphological stages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Comp. Biochem Physiol. B. 1986;83:533–536. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(86)90292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wassef MK, Fioretti TB, Dwyer DM. Lipid analyses of isolated surface membranes of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Lipids. 1985;20:108–115. doi: 10.1007/BF02534216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramos RG, et al. Comparison between charged aerosol detection and light scattering detection for the analysis of Leishmania membrane phospholipids. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1209:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becker GW, Lester RL. Biosynthesis of phosphoinositol-containing sphingolipids from phosphatidylinositol by a membrane preparation from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 1980;142:747–754. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.3.747-754.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lester RL, Dickson RC. Sphingolipids with inositolphosphate-containing head groups. Adv. Lipid Res. 1993;26:253–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sperling P, Heinz E. Plant sphingolipids: structural diversity, biosynthesis, first genes and functions. Biochim Biophys. Acta. 2003;1632:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S1388-1981(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Futerman AH, Hannun YA. The complex life of simple sphingolipids. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:777–782. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutterwala SS, et al. Developmentally regulated sphingolipid synthesis in African trypanosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70:281–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sevova ES, et al. Cell-free synthesis and functional characterization of sphingolipid synthases from parasitic trypanosomatid protozoa. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:20580–20587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pratt S, et al. Sphingolipid synthesis and scavenging in the intracellular apicomplexan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem Parasitol. 2013;187:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramakrishnan S, et al. Apicoplast and endoplasmic reticulum cooperate in fatty acid biosynthesis in apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:4957–4971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.310144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Botte CY, et al. Atypical lipid composition in the purified relict plastid (apicoplast) of malaria parasites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7506–7511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301251110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santiago TC, Zufferey R, Mehra RS, Coleman RA, Mamoun CB. The Plasmodium falciparum PfGatp is an endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein important for the initial step of malarial glycerolipid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9222–9232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin D, et al. Characterization of Plasmodium falciparum CDP-diacylglycerol synthase, a proteolytically cleaved enzyme. Mol. Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:93–105. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(00)00260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shastri S, et al. Plasmodium CDP-DAG synthase: an atypical gene with an essential N-terminal extension. Int J. Parasitol. 2010;40:1257–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lilley AC, Major L, Young S, Stark MJ, Smith TK. The essential roles of cytidine diphosphate-diacylglycerol synthase in bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;92:453–470. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kong P, et al. Two phylogenetically and compartmentally distinct CDP-diacylglycerol synthases cooperate for lipid biogenesis in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:7145–7159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.765487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Signorell A, Rauch M, Jelk J, Ferguson MA, Butikofer P. Phosphatidylethanolamine in Trypanosoma brucei is organized in two separate pools and is synthesized exclusively by the Kennedy pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:23636–23644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin KL, Smith TK. Phosphatidylinositol synthesis is essential in bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Biochem J. 2006;396:287–295. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta N, Hartmann A, Lucius R, Voelker DR. The obligate intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii secretes a soluble phosphatidylserine decarboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:22938–22947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.373639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartmann A, Hellmund M, Lucius R, Voelker DR, Gupta N. Phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis in the parasite mitochondrion is required for efficient growth but dispensable for survival of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:6809–6824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.509406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baunaure F, Eldin P, Cathiard AM, Vial H. Characterization of a non-mitochondrial type I phosphatidylserine decarboxylase in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:33–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibellini F, Hunter WN, Smith TK. The ethanolamine branch of the Kennedy pathway is essential in the bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;73:826–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serricchio M, Butikofer P. An essential bacterial-type cardiolipin synthase mediates cardiolipin formation in a eukaryote. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E954–E961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121528109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Serricchio M, Butikofer P. Phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase associates with a mitochondrial inner membrane complex and is essential for growth of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 2013;87:569–579. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Dooren GG, et al. Development of the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondrion and apicoplast during the asexual life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:405–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomova C, et al. Membrane contact sites between apicoplast and ER in Toxoplasma gondii revealed by electron tomography. Traffic. 2009;10:1471–1480. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sheiner L, Vaidya AB, McFadden GI. The metabolic roles of the endosymbiotic organelles of Toxoplasma and Plasmodium spp. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013;16:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huynh MH, Carruthers VB. Tagging of endogenous genes in a Toxoplasma gondii strain lacking Ku80. Eukaryot. Cell. 2009;8:530–539. doi: 10.1128/EC.00358-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vollmer M, Thomsen N, Wiek S, Seeber F. Apicomplexan parasites possess distinct nuclear-encoded, but apicoplast-localized, plant-type ferredoxin-NADP+reductase and ferredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:5483–5490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hager KM, Striepen B, Tilney LG, Roos DS. The nuclear envelope serves as an intermediary between the ER and Golgi complex in the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:2631–2638. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frenal K, et al. Functional dissection of the apicomplexan glideosome molecular architecture. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Achbarou A, et al. Differential targeting of dense granule proteins in the parasitophorous vacuole of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology. 1991;103:321–329. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000059837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stockdale PG, Stockdale MJ, Rickard MD, Mitchell GF. Mouse strain variation and effects of oocyst dose in infection of mice with Eimeria falciformis, a coccidian parasite of the large intestine. Int J. Parasitol. 1985;15:447–452. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(85)90032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmatz DM, Crane MS, Murray PK. Purification of Eimeria sporozoites by DE-52 anion exchange chromatography. J. Protozool. 1984;31:181–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb04314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/y59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brouwers JF, et al. Distinct lipid compositions of two types of human prostasomes. Proteomics. 2013;13:1660–1666. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith CA, Want EJ, O’Maille G, Abagyan R, Siuzdak G. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:779–787. doi: 10.1021/ac051437y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gajria B, et al. ToxoDB: an integrated Toxoplasma gondii database resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D553–D556. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Donald RG, Roos DS. Insertional mutagenesis and marker rescue in a protozoan parasite: cloning of the uracil phosphoribosyltransferase locus from Toxoplasma gondii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:5749–5753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.