Abstract

Objective

To develop a clinical practice guideline for a simplified approach to medical cannabinoid use in primary care; the focus was on primary care application, with a strong emphasis on best available evidence and a promotion of shared, informed decision making.

Methods

The Evidence Review Group performed a detailed systematic review of 4 clinical areas with the best evidence around cannabinoids: pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and adverse events. Nine health professionals (2 generalist family physicians, 2 pain management–focused family physicians, 1 inner-city family physician, 1 neurologist, 1 oncologist, 1 nurse practitioner, and 1 pharmacist) and a patient representative comprised the Prescribing Guideline Committee (PGC), along with 2 nonvoting members (pharmacist project managers). Member selection was based on profession, practice setting, location, and lack of financial conflicts of interest. The guideline process was iterative through content distribution, evidence review, and telephone and online meetings. The PGC directed the Evidence Review Group to address and provide evidence for additional questions as needed. The key recommendations were derived through consensus of the PGC. The guideline was drafted, refined, and distributed to a group of clinicians and patients for feedback, then refined again and finalized by the PGC.

Recommendations

Recommendations include limiting medical cannabinoid use in general, but also outline potential restricted use in a small subset of medical conditions for which there is some evidence (neuropathic pain, palliative and end-of-life pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and spasticity due to multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury). Other important considerations regarding prescribing are reviewed in detail, and content is offered to support shared, informed decision making.

Conclusion

This simplified medical cannabinoid prescribing guideline provides practical recommendations for the use of medical cannabinoids in primary care. All recommendations are intended to assist with, not dictate, decision making in conjunction with patients.

In Canada, 43% of people aged 15 years and older have used cannabis in their lifetime, with 12% having used cannabis in the past year.1 Men use cannabis more commonly than women do (16% vs 8%), with the highest use in those aged 18 to 24 years (33%).1 Among marijuana users in the United States, the most commonly reported reason for use was recreational in 53%, medicinal in 11%, and a mix in 36% of users.2 In many countries, including Canada, self-reported medical marijuana use, here defined as use of dried cannabis or cannabis oil, is often in the range of 15% to 19% for conditions like multiple sclerosis (MS), chronic pain, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 The most common reason for medical marijuana use is chronic pain, varying from 58% to 84% of medical marijuana users.3 Other reasons include mental health concerns (such as anxiety), sleep disorders, and spasticity in MS.3 Surveys of medical marijuana users find 70% or more believe medical marijuana use results in moderate or better improvement in their symptoms.3 A Canadian study found that functional status among medical marijuana users was worse than among the general population, reporting scores of 28 versus 7 on functional assessment, respectively (using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule for which possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing worse function).4

Medical marijuana use in Canada has grown sharply. On average, the number of registered medical marijuana users in Canada has approximately tripled every year since 2014, from 7914 in April to June of 2014, to 30 537 in 2015, to 75 166 in 2016, to 201 398 in 2017.5 The percentage of registered users in each province varies, ranging from 0.07% of the Quebec population to 1.7% of the Alberta population.5 Medical cannabinoids, here defined as medical marijuana and pharmaceutical cannabinoids, have been endorsed for a long list of medical concerns and ailments, from irritable bowel syndrome to cancer.6 However, enthusiasm among prescribers is inconsistent.7,8 Two Canadian surveys have shown that prescribers would appreciate more education and guidance around prescribing of medical cannabinoids.9,10

Although cannabinoids have been promoted for an array of medical conditions, the evidence base is challenged by bias and a lack of high-level research. Two large evidence synopses suggested that only 3 conditions have an adequate volume of evidence: chronic pain, nausea and vomiting, and spasticity.6,11 Therefore, our Evidence Review Group performed a targeted systematic review of systematic reviews on the use of cannabinoids for these conditions, as well as their potential adverse effects. Medical cannabinoids included pharmaceutically derived cannabinoids (nabilone and nabiximols) and medical marijuana. The clinical questions focused on medical cannabinoids as therapy; therefore, we selected systematic reviews that included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to focus on the highest-level evidence. Our systematic review, including GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) evaluation, is published in full as a companion document to this guideline (page e78).12 A summary of our recommendations is presented in Box 1.

Box 1. Recommendations summary.

General recommendation

- We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids for most medical conditions owing to lack of evidence of benefit and known harms (strong recommendation)

- -Potential exceptions are reviewed below: some types of pain, CINV, and spasticity due to MS or SCI

Management of pain

Acute pain: We strongly recommend against use of medical cannabinoids for acute pain management owing to evidence of no benefit and known harms (strong recommendation)

Headache: We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids for headache owing to lack of evidence and known harms (strong recommendation)

Rheumatologic pain: We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids for pain associated with rheumatologic conditions (including osteoarthritis and back pain) owing to lack of evidence and known harms (strong recommendation)

- Neuropathic pain: We recommend against medical cannabinoids as first- or second-line therapy in neuropathic pain owing to limited benefits and high risk of harms (strong recommendation)

- -Clinicians could consider medical cannabinoids for refractory neuropathic pain, with the following considerations (weak recommendation):

- — a discussion has taken place with patients regarding the benefits and risks of medical cannabinoids for pain

- — patients have had a reasonable therapeutic trial* of ≥ 3 prescribed analgesics† and have persistent problematic pain despite optimized analgesic therapy

- — medical cannabinoids are adjuncts to other prescribed analgesics

- Palliative (end-of-life) cancer pain: We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids as first- or second-line therapy for palliative cancer pain owing to limited benefits and high risk of harms (strong recommendation)

- -Clinicians could consider medical cannabinoids for refractory pain in palliative cancer patients, with the following considerations (weak recommendation):

- — a discussion has taken place with patients regarding the risks and benefits of medical cannabinoids for pain

- — patients have had a reasonable therapeutic trial* of ≥ 2 prescribed analgesics and have persistent problematic pain despite optimized analgesic therapy

- — medical cannabinoids are adjuncts to other prescribed analgesics

- Types of medical cannabinoids for pain:

- -If considering medical cannabinoids, we recommend a pharmaceutically developed product (nabilone or nabiximols) as the initial agent (strong recommendation)

- — Nabilone is off-label for pain and has limited evidence of benefit. However, it is less expensive than nabiximols and dosing is more consistent than for smoked cannabis

- — Nabiximols is expensive and, in some provinces, only available through specialist prescribing or special authorization. However, nabiximols has better evidence than nabilone does

- -If considering medical cannabinoids, we recommend against medical marijuana (particularly smoked) as the initial product (strong recommendation)

- — Evidence for smoked cannabis has a very high risk of bias, and long-term consequences are unknown

- — Products available can have far higher concentrations of THC and CBD than those researched

Management of nausea and vomiting

- General: We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids for general nausea and vomiting owing to the lack of evidence and known harms (strong recommendation)

- -We strongly recommend against medical cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy or hyperemesis gravidarum owing to the lack of evidence, known harms, and unknown harms (strong recommendation)

- CINV: We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids as first- or second-line therapy for CINV owing to limited comparisons with first-line agents and known harms (strong recommendation)

- -Clinicians could consider medical cannabinoids for treatment of refractory CINV, with the following considerations (weak recommendation):

- — a discussion has taken place with patients regarding the risks and benefits of medical cannabinoids for CINV

- — patients have had a reasonable therapeutic trial of standard therapies‡ and have persistent CINV

- — medical cannabinoids are adjuncts to other prescribed therapies

- Types of medical cannabinoids for CINV:

- -If considering medical cannabinoids, we recommend nabilone (strong recommendation)

- — We recommend against nabiximols and medical marijuana (smoked, oils, or edibles), as it is inadequately studied (strong recommendation)

- — While dronabinol has been studied, it is no longer available in Canada

Management of spasticity

General: We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids for general spasticity owing to lack of evidence and known harms (strong recommendation)

- Spasticity in MS or SCI: We recommend against use of medical cannabinoids as first- or second-line therapy for spasticity in MS or SCI owing to limited evidence and known harms (strong recommendation)

- -Clinicians could consider medical cannabinoids for refractory spasticity in MS and SCI, with the following considerations (weak recommendation):

- — a discussion has taken place with patients regarding the benefits and risks of medical cannabinoids for spasticity

- — patients have had a reasonable therapeutic trial of standard therapies (including nonpharmaceutical measures)§ and have persistent spasticity

- Types of medical cannabinoids for spasticity:

- -If considering medical cannabinoids, we recommend nabiximols (strong recommendation)

- — We recommend against medical marijuana (smoked, oils, or edibles), as it is inadequately studied (strong recommendation)

- — Clinicians could consider nabilone owing to its lower cost; however, it is off-label and lacks evidence for this use (weak recommendation)

CBD—cannabidiol, CINV—chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, MS—multiple sclerosis, SCI—spinal cord injury, THC—tetrahydrocannabinol.

*Reasonable therapeutic trial is defined as 6 wk of therapy with an appropriate dose, dose titration, and monitoring (eg, function, quality of life).

†Other prescribed therapies for neuropathic pain management include, but are not limited to (in no particular order), tricyclic antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline, nortriptyline), gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin), or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (duloxetine, venlafaxine). The committee believed that ≥ 3 medications should be trialed before considering cannabinoids or opioids.

‡Other prescribed therapies for CINV include, but are not limited to (in no particular order), serotonin antagonists (eg, ondansetron), neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists (aprepitant, fosaprepitant), corticosteroids (dexamethasone), and dopamine antagonists (prochlorperazine, metoclopramide).

§Other therapies for spasticity in MS include, but are not limited to (in no particular order), daily stretching, range-of-movement exercises, baclofen, gabapentin, tizanidine, dantrolene, benzodiazepine, or botulinum toxin.

METHODS

Following the completion of the systematic review, the guideline was begun by forming the overarching 10-member Prescribing Guideline Committee (PGC), which consisted of 2 generalist family physicians (G.M.A., M.F.), 1 inner-city family physician (J.K.), 2 pain management–focused family physicians (R.E.D., T.F.), 1 neurologist (K.M.), 1 medical oncologist (X.Z.), 1 nurse practitioner (N.C.), 1 pharmacist (N.P.B.), and 1 patient representative (B.D.). There were originally 11 members (2 patient members), but 1 patient representative withdrew owing to unavoidable external commitments. There were also 2 nonvoting members to help guide the process (pharmacist project managers: A.J.L., J.R.). The PGC was responsible for considering the evidence, discussing its application to primary care, developing and approving recommendations from primary care clinicians, assisting in drafting and preparing the guideline, and approving related knowledge translation content. The PGC member selections were based on profession, practice setting, and location to represent a variety of primary care providers from across the country, as well as on the absence of financial conflicts of interest. Actual and potential conflicts of interest were disclosed and are available at CFPlus.* This guideline received no external funding and no members of the PGC have financial conflicts of interest.

As with our previous guideline,13 we endeavoured to create an evidence-based, primary care–focused, patient-centred, and, wherever possible, simplified guideline. We followed the Institute of Medicine’s outline for Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust14 and the GRADE methodology.15 Guideline development itself was iterative and completed through online communication and telephone meetings.

As previously mentioned, the process started with identification of 3 possible areas of reasonable evidence for medical cannabinoids6,11 and the potential harms. The Evidence Review Group then performed a detailed systematic review12 of systematic reviews (of RCTs) in the following areas:

medical cannabinoids for the management of pain;

medical cannabinoids for the management of nausea and vomiting;

medical cannabinoids for the management of spasticity; and

adverse events resulting from medical cannabinoids.

The PGC members reviewed the results of the systematic reviews and completed premeeting work to formulate thoughts around key recommendations for primary care. Medical cannabinoids included pharmaceutically derived cannabinoids (eg, nabilone and nabiximols) and medical marijuana. At meetings, evidence and its application was discussed and the PGC began to compose key recommendations. Recommendations were further drafted between meetings, shared ahead, and then discussed at subsequent meetings. During this process, the PGC members had 7 additional questions they requested clarification on from the Evidence Review Group:

What is the evidence on medical cannabinoids for appetite stimulation?

Do cannabinoids reduce seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy?

Can cannabinoids be used to treat headaches?

Have there been any cases of pulmonary aspergillosis and, if so, was the cannabis smoked or vaporized?

What is the efficacy of oral cannabinoids in chronic pain?

Is there high-level evidence that differing proportions of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabidiol (CBD) influence effectiveness (or harms)?

How do cannabinoids compare to other drug treatments for neuropathic pain?

All 7 questions were answered using an abbreviated, focused search and summation of the best available evidence. The results were discussed at meetings while finalizing and approving key recommendations.

The principles of the GRADE methodology were used for wording of recommendations.15 Weak recommendations were represented by the wording “could consider.” Strong recommendations were represented by the wording “we recommend” and, for particular emphasis, the committee might also include the phrasing “we strongly recommend.” Four PGC members (G.M.A., N.P.B., J.R., A.J.L.) then completed the first draft of the guideline, which was distributed to the full PGC for consideration and suggestions. The PGC then met again to finalize the recommendations and document.

The guideline was given to the Peer Review Committee for distribution to outside clinicians and patients for peer review and feedback. The Peer Review Committee compiled feedback from 40 individuals and made suggestions to improve the guideline. Once edited, the guideline was sent to the PGC for final approval. After final approval of the guideline by the PGC, knowledge translation tools, including patient education content, were developed.

Evidence limitations

We focused on the best available evidence in our review. Systematic reviews or meta-analyses and RCTs offer the best possibility of addressing therapy questions, central to prescribing therapeutics. However, when examining cannabinoids, even this higher-level evidence is subject to multiple and highly influential biases, considerably influencing the GRADE evaluation.12 These are reviewed in detail in our systematic review12 but the primary issues are summarized here.

Many studies enrolled patients with a history of cannabinoid use. This might exaggerate the benefit of interventions and almost certainly minimizes adverse events. In fact, 1 systematic review found that rare serious adverse events, like psychosis, occurred predominantly among cannabinoid-naïve participants.16 Blinding was examined in some of the RCTs, asking patients and caregivers if they could identify when cannabinoids or placebos were being used. In all studies reporting on the issue, unblinding was very common (approximately 90%) for both patients and caregivers, regardless of cannabinoid type and dose.12 Additionally, RCTs with small sample sizes and short durations, with an increased potential of falsely positive results, are common in cannabinoid research. A sensitivity analysis on chronic pain RCTs found that results of smaller and shorter-duration RCTs were positive, while larger and longer RCTs found no effect. Other risk-of-bias issues for RCTs include missing quality markers, like allocation concealment. Risk-of-bias issues for systematic reviews include inconsistent inclusion of RCTs and inconsistent outcome reporting.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Shared, informed decision making

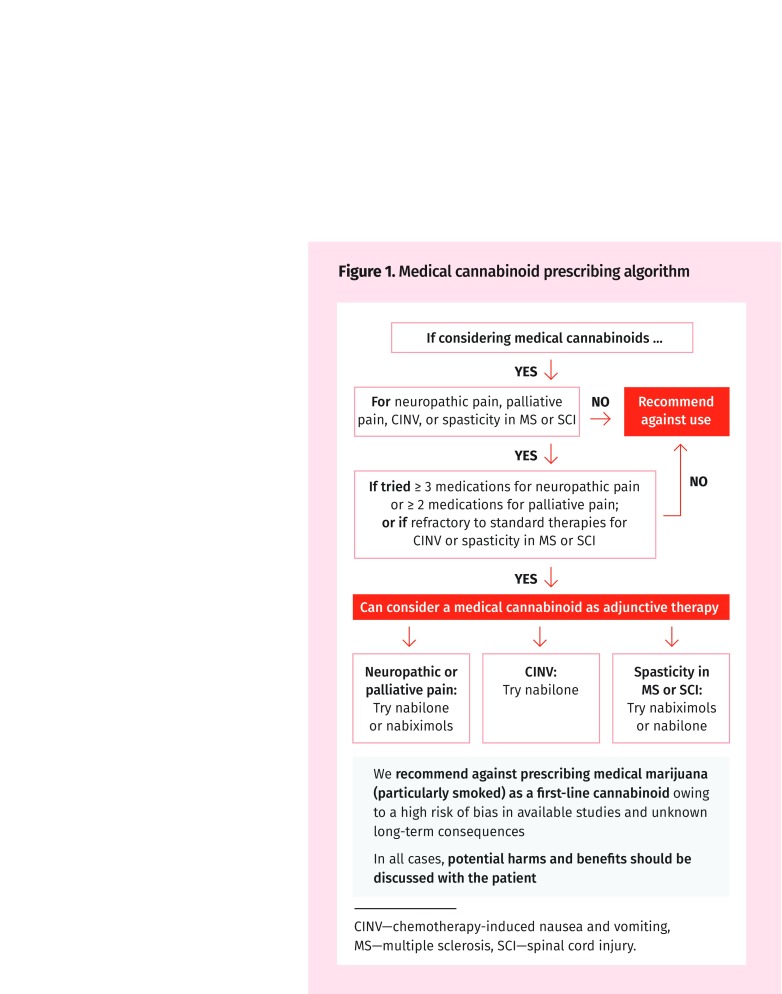

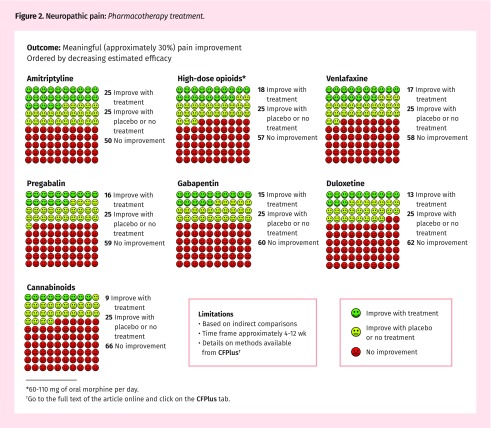

In addition to recommendations (Box 1), this guideline provides details that promote shared decision making with patients. The recommendations are also reflected in the simplified algorithm (Figure 1). Table 1 outlines the benefits for specific indications, including natural frequencies (event rates) and numbers needed to treat (with duration).12 Table 2 outlines common adverse events in both natural frequency (event rates) and numbers needed to harm.12 Last, Figure 2 provides a comparison icon array with natural frequencies for common interventions for neuropathic pain. This tool is not meant to recommend specific therapies but to allow clinicians and patients to see the estimated benefits of various interventions. Adverse events, costs, and patients’ preferences are some of the issues that also contribute to medication selection. For example, while high-dose opioids have benefits similar to venlafaxine or pregabalin, the risks and harms of high-dose opioids make them a poor choice. As a supplement, we provide a “1-pager” summarizing the key aspects of the guideline and shared decision making information, as well as a patient handout, available at CFPlus.*

Figure 1.

Medical cannabinoid prescribing algorithm

CINV—chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, MS—multiple sclerosis, SCI—spinal cord injury.

Table 1.

Medical cannabinoids’ estimated benefit when treating chronic pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, or spasticity with GRADE rating of evidence

| ESTIMATED BENEFIT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| INDICATION | CANNABINOIDS | CONTROL (PLACEBO UNLESS INDICATED) | NNT | GRADE QUALITY OF EVIDENCE |

| Chronic pain (median follow-up 4 wk) | ||||

| • ≥ 30% reduction in chronic (neuropathic plus cancer) pain* | 39% | 30% | 11 | Very low |

| • ≥ 30% reduction in neuropathic pain | 38% | 30% | 14 | Very low |

| • ≥ 30% reduction in palliative pain | 30% | 23% | NS (approximately 15)† | Very low |

| • Change in chronic pain scales (possible score 0–10)‡ | Baseline: approximately 6 Decrease: 1.2–1.6 |

Baseline: approximately 6 Decrease: 0.8 |

NA | Very low |

| Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (median follow-up 1 d) | ||||

| • Control of nausea and vomiting (cannabinoids vs placebo) | 47% | 13% | 3 | Moderate |

| • Control of nausea and vomiting (cannabinoids vs neuroleptics) | 31% | 16% (vs neuroleptics) | 7 | Low |

| Spasticity (median follow-up 6 wk) | ||||

| • Global impression of change | 50% | 35% | 7 | Low |

| • ≥ 30% improvement in spasticity | 35% | 25% | 10 | Low |

| • Change in spasticity (possible score 0–10)‡ | Baseline: 6.2 Decrease: 1.3–1.7 |

Baseline: 6.2 Decrease: 1.0 |

NA | Very low |

GRADE—Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation, NA—not applicable, NNT—number needed to treat, NS—not statistically significant. Data from accompanying systematic review by Allan et al (page e78).12

Meta-analysis results included 13 studies on neuropathic pain and 2 studies on cancer pain.

Confidence intervals suggest that benefit is likely (risk ratio = 1.34, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.86), so estimated NNT provided.

Scales are visual analogue scales or numeric rating scales with higher scores indicating worse pain or spasticity. Changes with cannabinoids are given as a range based on varying results.

Table 2.

Adverse events and estimated event rates for medical cannabinoids, with GRADE of evidence rated high

| TYPE OF ADVERSE EVENT | CANNABINOID EVENT RATE, % | PLACEBO EVENT RATE, % | NNH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 81 | 62 | 6 |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 11 | Approximately 3% | 14 |

| Serious adverse events | NS | NS | NS |

| Central nervous system effects | 60 | 27 | 4 |

| “Feeling high” | 35 | 3 | 4 |

| Sedation | 50 | 30 | 5 |

| Speech disorders | 32 | 7 | 5 |

| Dizziness | 32 | 11 | 5 |

| Ataxia or muscle twitching | 30 | 11 | 6 |

| Numbness | 21 | 4 | 6 |

| Disturbance in attention or disconnected thoughts | 17 | 2 | 7 |

| Hypotension | 25 | 11 | 8 |

| Dysphoria | 13 | 0.3 | 8 |

| Psychiatric | 17 | 5 | 9 |

| Euphoria | 15 | 2 | 9 |

| Impaired memory | 11 | 2 | 12* |

| Disorientation or confusion | 9 | 2 | 15 |

| Blurred vision or visual hallucination | 6 | 0 | 17 |

| Dissociation or acute psychosis | 5 | 0 | 20 |

GRADE—Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation, NNH—number needed to harm, NS—not statistically significant. Data from accompanying systematic review by Allan et al (page e78).12 Examples of harms were selected from the largest statistically significant meta-analyses providing event rates. Grouping of adverse events follows the combinations used in the original research.12

Confidence intervals suggest that harm is likely (risk ratio = 3.41, 95% CI 0.95–12.27), so estimated NNH provided.

Figure 2.

Neuropathic pain: Pharmacotherapy treatment.

*60–110 mg of oral morphine per day.

†Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Cannabinoids for most medical conditions

Although advocated for various medical conditions, the evidence for medical cannabinoids for most conditions is sparse.6 This guideline will deal specifically with pain, nausea and vomiting, and spasticity, as these conditions have both the greatest volume of evidence and research that supports a potential benefit. There is insufficient evidence, evidence indicating a lack of benefit, or both for most other conditions. For example, the evidence for glaucoma consists of 1 RCT of 6 patients that found no benefit.11 Even in areas with more research, such as appetite stimulation, RCT results are generally inconsistent and the results are frequently insignificant (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*). For example, of 4 appetite-stimulation RCTs in HIV, 2 found no difference compared with placebo, 1 found an approximately 2-kg improvement with cannabinoids versus placebo, and 1 found that megestrol improved weight by 8.5 kg more than cannabinoids did.11 For seizure disorders, a Cochrane systematic review reported 4 low-quality RCTs with 9 to 15 patients each, and did not find that there was any reliable information to support cannabinoids for seizure prevention (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*). Since then, a 2017 high-quality RCT of CBD for treatment-resistant seizures in Dravet syndrome (in patients aged 2 to 18 years) showed some improvement in the seizures.17 While positive, this type of condition would not be managed in primary care and is therefore not relevant to a primary care guideline.

While mental health concerns are a common reason for medical marijuana use,3 the evidence is very poor. There are no RCTs investigating medical cannabinoids for depression.6 The evidence for anxiety consists of 1 RCT of 24 patients who performed a simulated public speaking activity and then reported improvement on the mood visual analogue scale.11 The evidence for posttraumatic stress disorder consists of 1 RCT of 10 patients that found benefit in some outcomes, but these results disagree with other research findings of marijuana use worsening posttraumatic stress disorder.6 Overall, the present evidence for medical cannabinoids is insufficient to support use in mental health conditions.

The PGC recommends against the use of cannabinoids for most medical conditions, mostly owing to the known harms weighed against the lack of supporting evidence for benefit.

Pain

There was insufficient evidence for most subtypes of pain. For acute pain, 1 systematic review of 7 RCTs12 demonstrated that cannabinoids have no reliable effect compared with placebo. For headaches, only 1 small, flawed crossover RCT was identified (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*), meaning there was insufficient evidence to recommend cannabinoids for headache. For pain associated with rheumatologic conditions, 3 systematic reviews reported insufficient evidence for benefit in fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and back pain.12 Given these findings, and the high risk of harms, the PGC recommends against cannabinoids for these conditions.

Neuropathic pain

Cannabinoid use increased the number of patients who achieved a 30% pain reduction in chronic (13 neuropathic and 2 cancer RCTs) pain, with a risk ratio of 1.37 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.64).12 Looking specifically at neuropathic pain, in the largest meta-analysis (9 RCTs) cannabinoid use increased the number of patients who achieved a 30% pain reduction, with a risk ratio of 1.34 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.74). Given that the chronic pain meta-analyses were larger (specifically, ≥ 10 RCTs), we performed sensitivity analyses on this group of studies and demonstrated that longer or larger RCTs found no effect in chronic pain.12 This raises considerable uncertainty regarding cannabinoids’ true effect on chronic pain. Additionally, even if we assume estimated benefits are real, many of the adverse events are more common than the benefits. Weighing this information, and the fact that many other agents are more effective with fewer harms, the PGC believed that clinicians should only consider cannabinoids after patients have had a reasonable therapeutic trial of 3 or more established agents for neuropathic pain.

It is also important to note that most pain studies used cannabinoids with concomitant analgesia.12 Therefore, if cannabinoids are used, it should be as adjuncts to other analgesics. Other research shows almost half of patients with neuropathic pain will require at least 2 agents.18 Although HIV-related neuropathy is often unresponsive to other analgesics, the evidence for cannabinoids for this indication is highly biased and unreliable. For example, 2 studies in HIV neuropathic pain were both short (< 2 weeks) and small (34 and 55 patients).11 Therefore, the PGC was not able to provide a specific recommendation for this indication beyond that for general neuropathic pain.

Cancer and palliative pain

The research for medical cannabinoids in cancer and palliative pain is not as robust as for neuropathic pain. However, the PGC considered the potential, although not reliably verified, for concurrent small benefits for nausea and vomiting and appetite stimulation (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*), as well as the reduced concern about long-term adverse effects in this population. This led to a weak recommendation for considering use in refractory cancer or palliative pain. Weighing these deliberations with the reality that the management of cancer and palliative pain progresses more rapidly to opioid analgesia compared with other chronic pain conditions, the PGC believed that clinicians should only consider cannabinoids after patients have had a reasonable therapeutic trial of 2 or more established agents for cancer or palliative pain.19

Nausea and vomiting

Owing to the absence of evidence and the known harms of medical cannabinoids, the PGC recommends against cannabinoids for general nausea and vomiting. Owing to the additional unknown harms to an unborn fetus caused by medical cannabinoids in pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting or hyperemesis gravidarum, the recommendation against cannabinoid use for these conditions was strengthened.

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) remains a common consequence of cancer treatment. Meta-analysis (7 RCTs) shows that medical cannabinoids (nabilone or dronabinol) help more patients avoid CINV, with a risk ratio of 3.60 (95% CI 2.55 to 5.09).12 However, 4 of the 7 RCTs were at least 35 years old and would not have included therapies in current use. Further, many RCTs followed patients for only 1 day. Current recommended treatments of CINV depend on the emetogenicity of the selected chemotherapy protocol and classification of the symptoms (acute onset, delayed onset, anticipatory). Contemporary recommended treatments for CINV often include ondansetron, dexamethasone, and aprepitant, with metoclopramide prescribed as needed.20 Weighing these considerations, the PGC believed that medical cannabinoids could only be considered for CINV refractory to current antiemetic therapies.

Spasticity

Owing to the limited evidence for use in spasticity (other than in MS or spinal cord injury [SCI]) and the known harms of medical cannabinoids, the PGC recommended against the use of medical cannabinoids for general spasticity.

Spasticity in MS and SCI

Spasticity is a common symptom in MS and SCI. In MS, meta-analysis (3 RCTs) showed that medical cannabinoids (nabiximols) increased the number of patients achieving a 30% improvement in spasticity, with a risk ratio of 1.37 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.76).12 Although the number of RCTs in SCI is far lower (3 vs 11 for MS), the trials generally show similar results.11 However, the PGC recognized that there are a number of established therapies for spasticity (for example, see the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline21). Furthermore, nabiximols are very expensive and, as with all medical cannabinoids, adverse events are more common than benefits are. Therefore, the PGC thought medical cannabinoids could only be considered for MS or SCI spasticity refractory to current established therapies. Last, the PGC believed it was important to differentiate spasticity from spasms, as the recommendation does not apply to spasms.

Harms of cannabinoids

Harms of cannabinoids were consistent and common across all prescribing considerations. Further, harms were consistent within research trials and represent the highest level of GRADE evidence within the accompanying systematic review.12 Table 2 provides a list of adverse events.12 The GRADE evaluation of evidence started as high (from meta-analyses of RCTs) but decreased owing to risk of bias and imprecision. However, GRADE evaluation also increased for large magnitudes of effect and confounders that would decrease adverse events (like selective inclusion of past cannabinoid users). This meant that the final GRADE evidence rating for adverse events was high.

Across studies, the approximate risk of adverse events is 80% versus 60%, and withdrawal due to adverse events is 11% versus 3%, for cannabinoids and placebo, respectively.12 The overall risk of adverse events is similar among varying types of medical cannabinoids (such as nabiximols or medical marijuana).11 Certain adverse events, relative to controls, like “feeling high” (35% to 70% vs 0% to 3%) and euphoria (15% vs 2%), are very common, but likely anticipated.12 Other common adverse events, which were potentially less desirable and more relevant to the committee, include sedation (50% vs 30%), dysphoria (13% vs 1%), disorientation or confusion (9% vs 2%), disturbed attention or disconnected thoughts (17% vs 2%), dizziness (32% vs 11%), and hypotension (25% vs 11%).12

Long-term and serious adverse events are underestimated in our systematic review owing to our focused use of meta-analyses of RCTs. This is exacerbated by enrolment of previous cannabinoid users in the RCTs and the predominance of small RCTs with short durations. As a result, the risk of psychosis appears to be underestimated.16 The risks of rare events, such as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (cyclic vomiting) and amotivational syndrome, are still being defined.22,23

Cannabis use disorder (CUD), replacing previous cannabis abuse and cannabis dependence, might be as common as appearing in one-fifth of regular cannabis users.6 Risk of CUD is higher in those who use more frequently, are male, and begin at a younger age.6,24 However, in another study of those meeting criteria for having CUD, 67% remitted (no longer met criteria) at 3 years, with 64% of them no longer using cannabis.25 Whether regular medical use might result in CUD, what outcomes this might have, and if discontinuation presents concerns are all not well understood.

Prescribing considerations

Pharmaceutical cannabinoids (nabilone and nabiximols)

Prescribing for CINV should focus on nabilone, and for spasticity in MS or SCI nabiximols should be used, based on the evidence and marketing authority in Canada. The PGC recognized that nabilone, an oral synthetic cannabinoid, is used off-label for pain and has limited evidence of benefit. However, it is relatively inexpensive, is covered by many public drug plans, and can be dosed more consistently owing to its capsule formulation. Nabiximols is a combination of THC and CBD available as an oromucosal spray. It is expensive, is rarely covered on public drug plans, and has limitations to prescribing in some Canadian provinces. However, nabiximols has better evidence for spasticity and neuropathic pain.

Smoked and other medical marijuana

The PGC recognizes that when patients request medical cannabinoids they are likely considering smoked and other medical marijuana formulations. Reasons for this include symptom improvement with previous cannabis experience; secondary gain related to known cannabinoid effects; patients’ desire to use a natural product; information from media, the Internet, or personal contacts; or unawareness of other formulations available. Regardless, there are a number of important considerations. First, the literature around smoked medical marijuana demonstrates a considerable risk of bias, including possibly exaggerated benefits and underreported harms.12 Second, the long-term harms (including smoking) and serious adverse effects would not be adequately captured in RCTs and so are largely unknown. Third, dosing with medical marijuana poses an issue, as THC and CBD concentrations vary considerably with differing medical marijuana products. In fact, many dried medical marijuana products have THC concentrations of 15% or greater, while the highest concentration studied is only 9.4%.26 Additionally, mode of delivery and volume per use can substantially change total intake. There is no evidence that the different formulations of medical marijuana, such as cannabis oil, are more effective or safer than dried medical marijuana. Last, cases of pulmonary aspergillosis have been reported in immunocompromised patients (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*).

Medical recommendations in the literature are often for small amounts of lower-potency marijuana.27 For example, the starting recommended dosing is 1 inhalation of a 9% maximum THC “joint” once per day.27 This can be increased to 1 inhalation 4 times a day, resulting in approximately half a “joint” per day (or 400 mg).27 People should not operate dangerous equipment or perform potentially dangerous activities after use. This includes no driving for 3 to 4 hours after inhaled medical marijuana, 6 hours after oral medical marijuana, and 8 hours if a “high” was noted. For further specific recommendations, monitoring, and guidance regarding prescribing medical marijuana, we suggest the guidance document by Kahan et al from 2014.27 There are also many national and provincial associations, colleges, and governmental groups that provide policy and guidance for prescribers (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*). We provide a summary of the provincial guidance and a list of authorized licensed producers of medical marijuana in the online supplement at CFPlus.* It should be noted that licensed providers often do not involve authorizing clinicians in the titration of medical marijuana and might simply allow patients to select medical marijuana types. It should be clear that if patients use 5 g (current maximum) of 15% THC, this represents approximately 20 times higher dosing than the recommended 400 mg of 9% THC.

At the time of writing, prices from licensed producers (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*) ranged from $4.25 to $15 per gram. Public Safety Canada reported the mean (SD) price from licensed producers was $8.37 ($2.34) per gram.28 Given that most patients smoke 1 to 3 g per day (compared to the recommended 400 mg per day),27 typical costs would be approximately $250 to $750 per month.

We have indicated authorized licensed providers that provide space for clinician recommendations (see the online supplement available at CFPlus*). Last, it should be noted that, in whatever form cannabinoids are taken, they can have interactions with other pharmaceuticals, with particular concerns about increased central nervous system effects.

Conclusion

Medical cannabinoids challenge clinicians, particularly as we attempt to provide symptom and functional improvement in patients whose conditions are refractory to other therapies. The evidence for medical cannabinoids is unfortunately sparse in many areas and very frequently downgraded by serious bias, limiting the ability to provide clear guidance. Overall, the PGC believed that medical cannabinoids are not recommended for most patients and conditions by far. In neuropathic pain, palliative cancer pain, CINV, and MS- or SCI-related spasticity, they should only be considered for patients whose conditions are refractory to standard medical therapies. When considered, there should be a discussion with patients regarding the limited benefits and more common harms, and a preferential trial of pharmaceutical cannabinoids first (over medical marijuana). We hope that future high-quality RCTs will clarify the evidence further and that that might lead to reevaluation of the recommendations. We also recommend long-term monitoring of medical cannabinoids to further assess potential individual and societal benefits and harms.

Acknowledgments

Drs Allan, Korownyk, and Kolber received salary support from the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta. Dr Ton, Ms Perry, Mr Ramji, and Dr Noël received salary support from the Physician Learning Program of the Alberta Medical Association. Ms Nickel and Dr Lindblad received salary support from the Alberta College of Family Physicians. Dr McCormack received salary support from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of British Columbia. The remaining contributors’ work was unfunded and the project did not receive any funding. This guideline was endorsed by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Editor’s key points

▸ This simplified prescribing guideline was developed with a primary care focus. Guideline contributors were selected based on profession, practice setting, and location to represent a variety of key stakeholders (particularly primary care) from across the country, as well as on the absence of financial conflicts of interest.

▸ Although cannabinoids have been promoted for an array of medical conditions, the evidence base is challenged by bias and a lack of high-level research. Two large evidence synopses suggested that only 3 conditions have an adequate volume of evidence to inform prescribing recommendations: chronic pain, nausea and vomiting, and spasticity.

▸ The guideline suggests that clinicians could consider medical cannabinoids for refractory neuropathic pain and refractory pain in palliative care, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and spasticity in multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury after reasonable trials of standard therapies have failed. If considering medical cannabinoids and criteria are met, the guideline recommends nabilone or nabiximols be tried first. Harms are generally more common than benefits are, and it is important to discuss the benefits and risks of medical cannabinoids with patients for whom they are being considered.

Footnotes

The full disclosure of competing interests, the 1-page summary, a patient handout, and the online supplement are available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Contributors

Drs Allan, Fleming, Kirkwood, Dubin, Findlay, Makus, Zhu, Beahm, and Lindblad and Ms Crisp, Ms Dockrill, and Mr Ramji comprised the Prescribing Guideline Committee. Drs Korownyk, Kolber, and Lindblad and Ms Nickel comprised the Peer Review Committee. Drs Allan and Ton, Ms Perry, Mr Ramji, and Dr Lindblad comprised the Evidence Review Group. Ms Nickel, Ms Perry, Drs McCormack and Noël, Mr Ramji, and Drs Ton and Allan comprised the Knowledge Translation Team.

Competing interests

This guideline received no external funding and no members of the Prescribing Guideline Committee or any other authors have a financial conflict of interest. The full disclosure is available at CFPlus.*

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de février 2018 à la page e64.

References

- 1.Rotermann M, Langlois K. Prevalence and correlates of marijuana use in Canada, 2012. Health Rep. 2015;26(4):10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE, Promoff G, McAfee TA. Toking, vaping, and eating for health or fun: marijuana use patterns in adults, U.S., 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.027. Epub 2015 Aug 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park JY, Wu LT. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects, and correlates of medical marijuana use: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.009. Epub 2017 May 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer B, Ialomiteanu AR, Aeby S, Rudzinski K, Kurdyak P, Rehm J. Substance use, health, and functioning characteristics of medical marijuana program participants compared to the general adult population in Ontario (Canada) J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(1):31–8. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2016.1264648. Epub 2016 Dec 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health Canada. Market data. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2017. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medical-use-marijuana/licensed-producers/market-data.html. Accessed 2017 Sep 12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids. The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lake S, Kerr T, Montaner J. Prescribing medical cannabis in Canada: are we being too cautious? Can J Public Health. 2015;106(5):e328–30. doi: 10.17269/cjph.106.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel L. Cautious first guidance for prescribing pot. CMAJ. 2014;186(16):E595. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St-Amant H, Ware MA, Julien N, Lacasse A. Prevalence and determinants of cannabinoid prescription for the management of chronic noncancer pain: a postal survey of physicians in the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region of Quebec. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E251–7. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziemianski D, Capler R, Tekanoff R, Lacasse A, Luconi F, Ware MA. Cannabis in medicine: a national educational needs assessment among Canadian physicians. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:52. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0335-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. Errata in: JAMA 2016;315(14):1522, JAMA 2015;314(21):2308, JAMA 2015;314(5):520, JAMA 2015;314(8):837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allan GM, Finley CR, Ton J, Perry D, Ramji J, Crawford K, et al. Systematic review of systematic reviews for medical cannabinoids. Pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and harms. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:e78–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allan GM, Lindblad AJ, Comeau A, Coppola J, Hudson B, Mannarino M, et al. Simplified lipid guidelines. Prevention and management of cardiovascular disease in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:857–67. (Eng), e439–50 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenfield S, Steinberg EP, Auerbach A, Avorn J, Galvin R, Gibbons R, et al. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011. Available from: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust.aspx Accessed 2017 Oct 9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.013. Epub 2013 Jan 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreae MH, Carter GM, Shaparin N, Suslov K, Ellis RJ, Ware MA, et al. Inhaled cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Pain. 2015;16(12):1221–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.07.009. Epub 2015 Sep 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, Marsh E, Miller I, Nabbout R, et al. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2011–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarride JE, Collet JP, Choinere M, Rousseau C, Gordon A. The economic burden of neuropathic pain in Canada. J Med Econ. 2006;9(1–4):55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Family Practice Oncology Network, Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Palliative care for the patient with incurable cancer or advanced disease part 2: pain and symptom management. Victoria, BC: BC Guidelines; 2017. Available from: www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/bc-guidelines/palliative2.pdf. Accessed 2017 Oct 18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ettinger DS, Berger MJ, Aston J, Barbour S, Bergsbaken J, Bierman PJ, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Antiemesis. Version 2. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2017. Available from: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#antiemesis. Accessed 2017 Oct 18. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multiple sclerosis in adults: management. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG186/chapter/1-Recommendations#ms-symptom-management-and-rehabilitation-2. Accessed 2017 Oct 16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, Phillips KT, Monte AA. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment—a systematic review. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13(1):71–87. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0595-z. Epub 2016 Dec 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawn W, Freeman TP, Pope RA, Joye A, Harvey L, Hindocha C, et al. Acute and chronic effects of cannabinoids on effort-related decision-making and reward learning: an evaluation of the cannabis ‘amotivational’ hypotheses. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233(19–20):3537–52. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4383-x. Epub 2016 Sep 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society of Addiction Medicine . Public policy statement on marijuana, cannabinoids and legalization. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2015. Available from: www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/marijuana-cannabinoids-and-legalization-9-21-2015.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed 2017 Sep 27. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feingold D, Fox J, Rehm J, Lev-Ran S. Natural outcome of cannabis use disorder: a 3-year longitudinal follow-up. Addiction. 2015;110(12):1963–74. doi: 10.1111/add.13071. Epub 2015 Aug 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLeod SA, Lemay JF. Medical cannabinoids. CMAJ. 2017;189(30):E995. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahan M, Srivastava A, Spithoff S, Bromley L. Prescribing smoked cannabis for chronic noncancer pain. Preliminary recommendations. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:1083–90. (Eng), e562–70 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellet M, Macdonald M, Bouchard M, Morselli C, Frank R. The price of cannabis in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Public Safety Canada; 2017. Available from: www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2017-r005/2017-r005-en.pdf. Accessed 2017 Dec 3. [Google Scholar]