Abstract

Please cite this paper as: Van Buynder et al. (2010) Protective effect of single‐dose adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine in children. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 4(4), 171–178.

Background During the first wave of A/California/7/2009(H1N1) influenza, high rates of hospitalization in children under 5 years were seen in many countries. Subsequent policies for vaccinating children varied in both type of vaccine and number of doses. In Canada, children 36 months to <10 years received a single dose of 0·25 ml of the GSK adjuvanted vaccine (Arepanrix™) equivalent to 1·9 μg HA. Children 6 months to 35 months received two doses as did those 36–119 months with chronic medical conditions.

Method We conducted a community‐based case–control vaccine effectiveness (VE) review of children under 10 years with influenza like illness who were tested for H1N1 infection at the central provincial laboratory. Laboratory‐confirmed influenza was the primary outcome, and vaccination status the primary exposure to assess VE after a single 0·25‐ml dose.

Results If vaccination was designated to be effective after 14 days, no vaccinated child had laboratory‐confirmed influenza compared to 38% of controls. The VE of 100% was statistically significant for children <10 years of age and <5 years considered separately. If vaccination was considered effective after 10 days, VE dropped to 96% overall but was statistically significant and over 90% in all age subgroups, including those under 36 months.

Conclusions A single 0·25‐ml dose of the GSK adjuvanted vaccine (Arepanrix™) protects children against laboratory‐confirmed pandemic influenza potentially avoiding any increased reactogenicity associated with second doses. Adjuvanted vaccines offer hope for improved seasonal vaccines in the future.

Keywords: adjuvanted, effectiveness, influenza, Paediatric, pandemic, vaccination

Introduction

In many countries, the epidemiology of the first wave of pandemic infection with A/California/7/2009(H1N1) influenza included high rates of hospitalization in children particularly those <5 years of age. 1 , 2 Prevention of confirmed seasonal influenza with inactivated influenza vaccine in healthy children has been shown to be reasonably effective, 59% in a systematic review (CI 41–71%) 3 although two doses were necessary to protect in the first year of administration.

Initial pediatric studies using the GSK Biologicals candidate pandemic influenza vaccine in five Spanish centers in children aged 6–35 months showed that all 51 children given a single dose of vaccine comprising 1·9 μg haemagglutinin (HA) from the A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)v‐like strain combined with AS03B adjuvant were seropositive for A/California/7/2009 antibodies and had high geometric mean titers suggestive of protection on day 21. 4

Arepanrix™ (GSK, Quebec, Canada) is a two‐component vaccine consisting of an H1N1 immunizing antigen, as a suspension, and an ASO3 adjuvant, as an oil in water emulsion comprising DL‐α‐tocopherol, squalene, and polysorbate 80. 5

In the province of New Brunswick, Canada, children 36 months to <10 years received a single dose of 0·25 ml of the GSK adjuvanted vaccine (Arepanrix™) equivalent to 1·9 μg HA. Children 6 months to 35 months received two doses, not <21 days apart, as did those 36 months–<10 years with chronic medical conditions. This regime was consistent with the recommendations of the Public Health Agency of Canada for pandemic vaccine rollout.

In New Brunswick, all children were declared a priority group for receipt of early vaccine in view of the increased risk of serious infection and the role of children in community transmission. The second wave of the pandemic commenced in the week beginning October 25th, the same week that vaccine administration commenced, and by the end of week 2, November 7th, over 60% of children under 10 years had had their first dose of vaccine. Children 5–9 years were largely vaccinated in elementary schools, and younger children were vaccinated in mass clinics, so in the first 2 weeks, there were slightly more older children vaccinated.

New Brunswick was spared the effect of the first wave of the pandemic in the spring–summer period with only three hospitalized cases of laboratory‐confirmed influenza, thus immunity following previous infection was minimal in the province.

We conducted a case–control vaccine effectiveness (VE) review to determine the protective effectiveness of a single dose in those 3 years and older and also to ascertain the need for a second dose in those under 3 years where a potential existed for increased reactogenicity. Vaccination clinics commenced in the week beginning October 26th, and our review commenced 3 weeks later on November 16th.

Methods

All requests for H1N1 testing in the province are referred to a single central laboratory and information on the patients, and the results transferred to the Communicable Disease Control Branch (CDCB) of the Office of the Chief Health Medical Officer of Health. Pandemic influenza infection is a notifiable disease in New Brunswick.

Under provincial guidelines, H1N1 testing consisted of nasopharyngeal swabs collected with flocked dacron swabs and inoculated in viral transport medium (VTM). Samples were stored and shipped at +4°C to the Georges Dumont Laboratory. Once received, samples were processed and tested on the same day. Swabs were discarded, and VTM was centrifuged. The supernatants were retrieved and stored at +4°C until tested. Two hundred microliters of each sample was inactivated prior to extraction. Once inactivated, the sample’s RNA was extracted on a Roche MagNAPure Compact or Roche MagNAPure LC automated extractor, using the MagnaPure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation kit 1 or the MagNA Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit‐High Performance. Five microliters of each sample‐extracted RNA was added to a master mix containing 2% DMSO and Influenza A primers and probes directed at the matrix gene 6 and tested by real‐time PCR for 45 cycles on Roche LightCycler 2 instruments. Samples called positive by the instruments, with a visible amplification curve and a crossing point value below 40, were considered positive. Positive samples were then subtyped for Influenza A pH1N1 2009 by real‐time PCR on the same instruments using the Roche RealTime ready Influenza A/H1N1 Detection kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Commencing on November 16th, 21 days after the commencement of the pandemic vaccination campaign, we selected all children throughout New Brunswick, 6 months–9 years of age, who were tested for H1N1. The delayed commencement allowed 14 days for the vaccine to have taken effect and time for subsequent development of symptoms and submission of PCR test. The parents of all children tested for H1N1 were contacted and asked if they would agree to a telephone interview. Our study continued until December 2nd when high childhood vaccination rates produced a virtual end of the second wave of the pandemic in New Brunswick.

Children were classified as cases if the respiratory sample was H1N1 positive. They were classified as a control if the test was negative and the child met a clinical case definition of influenza‐like illness (the presence of fever and at least one respiratory symptom or sign). Information on age, sex, hospitalization, indigenous status, prematurity, immunosuppression, coexisting medical conditions, previous seasonal vaccination, and recent pandemic vaccination was collected by direct telephone interview. We also confirmed the diagnosis of an influenza‐like illness (ILI) in the child using a simple questionnaire. The interviews were conducted by staff from CDCB.

We confirmed the reported vaccination status and date of vaccination through access to New Brunswick’s universal pandemic vaccination registration program. This program recorded the personal details of every person vaccinated in New Brunswick including the date of administration.

Children were classified as vaccinated if the child had received a dose of the H1N1 vaccine at least 14 days before the onset of symptoms and as ‘not vaccinated’ if the child received no vaccination or received the first dose <14 days before the onset of symptoms. No child in the study was 14 days post receipt of a second dose of vaccine.

A secondary analysis was conducted classifying children as vaccinated if the child had received a dose of the H1N1 vaccine at least 10 days before the onset of symptoms and as ‘not vaccinated’ if the child received no vaccination or received the first dose <10 days before the onset of symptoms. Again, no child was 10 days post receipt of a second dose of vaccine.

Data were entered and analyzed in SAS version 9·1·3 SP4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Differences in categorical variables were tested by the chi‐square test or Fisher’s exact test if any expected cell sizes were less than five. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated using laboratory‐confirmed influenza as the primary outcome and vaccination status as the primary exposure. VE was calculated as 1‐OR.

Conditional multivariate analysis was undertaken with cases vaccinated at least 10 days previously. The potential confounding variables, age >35 months, First Nation status, receipt of seasonal vaccine, pre‐existing medical conditions, gender, and hospitalization, were added stepwise into the model along with receipt of pandemic vaccine. Confounders were also assessed individually in this model.

Results

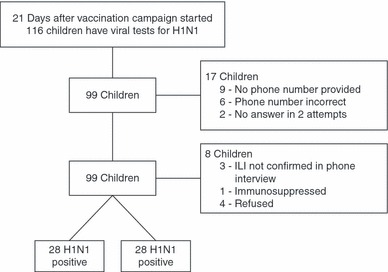

During the review period, a total of 116 children in the target age group were tested for H1N1 infection. Of these, 17 children were not contactable because they either had no phone number (nine), the number available was disconnected or incorrect (six), or no answer was received after three calls (two). Of the 99 children initially enrolled, four controls failed to meet the ILI qualification, three refused to participate, and one child was excluded because of immunosuppression, leaving 91 children who participated. Of these, 28 were cases and 63 were controls. (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Characteristics of Study Selection.

The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. A comparison of cases and controls showed no significant differences in gender, the proportion of First Nation/Aboriginal people, nor of those with a pre‐existing medical condition. Cases were more likely to have been in the 36–59 month age group (P = 0·05) and to have been hospitalized than controls, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0·13). In multivariate analysis, neither of these was significant as a confounder.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population

| H1N1 positive (N = 28) | H1N1 negative (N = 63) | P values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Age group | 6–35 months | 9 | 32 | 28 | 44 | 0·051 |

| 36–59 months | 9 | 32 | 7 | 11 | ||

| 60–119 months | 10 | 36 | 28 | 44 | ||

| Sex | Male | 14 | 50 | 33 | 52 | 0·834 |

| First Nation/Aboriginal | Yes | 4 | 14 | 5 | 8 | 0·449* |

| Hospitalized | Yes | 5 | 18 | 21 | 33 | 0·131 |

| Pre‐existing medical condition | Yes | 4 | 14 | 15 | 24 | 0·302 |

| Received a dose of H1N1 vaccine pre‐diagnosis | <10 days | 7 | 25 | 16 | 25 | |

| <14 days | 8 | 29 | 21 | 33 | ||

| 14 days or more | 0 | 0 | 24 | 38 | ||

| None | 20 | 71 | 18 | 29 | ||

| Received seasonal flu vaccine in 2009 | Yes | 5 | 18 | 12 | 19 | 0·893 |

*Fisher’s exact test.

There was no evidence that children who had received a dose of seasonal influenza were more likely to be diagnosed with H1N1 infection either in univariate (Table 1) or multivariate analysis (Table4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis (vaccinated at least 10 days prior to disease)

| Odds ratio estimates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Effect | Point estimate | 95% CI |

| Received pandemic vaccine | 0·037 | 0·005 – 0·302 |

| Age > 35 months | 0·373 | 0·115 – 1·212 |

| Male gender | 0·782 | 0·258 – 2·372 |

| Pre‐existing medical condition | 0·409 | 0·088 – 1·900 |

| Received seasonal vaccine | 1·327 | 0·291 – 6·050 |

| First Nations Ethnicity | 2·608 | 0·450 – 15·123 |

| Hospitalized | 0·320 | 0·086 – 1·193 |

A comparison of those vaccinated and unvaccinated revealed that those vaccinated were slightly older, although this was not statistically significant (P = 0·16). Those vaccinated were also more likely to be boy (P = 0·03). There were no differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups in the proportions of those hospitalized, with a pre‐existing medical condition or identifying as First Nation/Aboriginal.

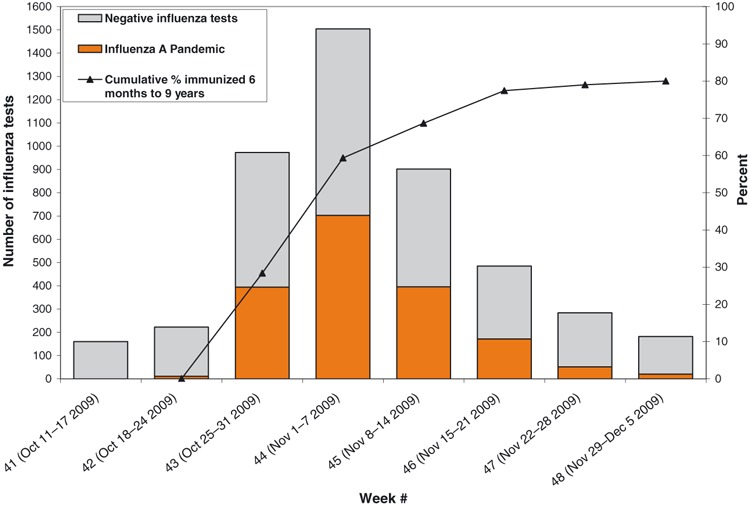

The overall rate of receipt of any vaccine dose in review participants, including those doses within 10 days or 2 weeks of symptom onset and too late to produce effective immunogenicity, was 58% (53/91). This was similar to the overall population statistics during the study period (Figure 2) where vaccination coverage of children reached 60% by the middle of November.

Figure 2.

Number of positive pandemic influenza specimens and percent of immunized between 6 months to 9 years with H1N1 vaccine in New Brunswick, up to December 5, 2009. Data source: G. Dumont lab results and CSDS Immunization data.

All the cases receiving vaccine (8/8, 100%) did so in the 14 days prior to symptom onset, and about half the controls (21/45, 47%) also received vaccine within 2 weeks. One case received vaccine in the period 10–14 days after symptom onset as did five controls. Two controls had received a second dose of vaccine, both only 1 day before symptom onset.

The proportion of children in the study that were vaccinated more than 14 days prior to symptom onset was 26%. However, no cases were vaccinated more than 14 days prior, compared to 38% (24/63) of controls. The resultant odds ratio of zero yields a VE of 100% for a single dose of 0·25 ml of vaccine. The data analysis is shown by age groupings in Table 2, and the VE is statistically significant for children overall (100%, CI 79·5–100), and for children under (100%, CI 44–100) and over 5 years of age (100%, CI 56·6–100), considered separately. The small numbers just prevent statistical significance for children 6 months to <3 years (VE = 100%, CI −25·7 to 100) but is significant for the 36 months and over group (VE = 100%, CI 75·5–100).

Table 2.

Vaccine effectiveness comparisons (vaccinated = at least 14 days prior to disease)

| H1N1+ | H1N1− | Point estimate | Vaccine effectiveness (VE) 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children 6–119 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 0 | 24 | P = 0·0001, VE = 100% | 79·5–100% |

| Not vaccinated | 28 | 39 | ||

| Total | 28 | 63 | ||

| Children 6–59 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 0 | 10 | P < 0·01, VE = 100% | 44·0–100% |

| Not vaccinated | 18 | 25 | ||

| Total | 18 | 35 | ||

| Children 60–119 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 0 | 14 | P = 0·004, VE = 100%* | 56·6–100% |

| Not vaccinated | 10 | 14 | ||

| Total | 10 | 28 | ||

| Children 6–35 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 0 | 8 | P = 0·08* | −25·7–100% |

| Not vaccinated | 9 | 20 | ||

| Total | 9 | 28 | ||

| Children 36–119 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 0 | 16 | P < 0·001, VE = 100%* | 75·5–100% |

| Not vaccinated | 19 | 19 | ||

| Total | 19 | 35 | ||

*Fisher’s exact one‐sided test statistic used as an expected cell size <5 present. Other estimate chi‐Square.

The analysis was repeated with children regarded as effectively vaccinated if they had received vaccine 10 days prior to symptom onset. The proportion regarded as vaccinated in the study increased to 33% (30/91), but only one case was vaccinated (3·5%) compared to 46% (29/63) of controls. While the overall childhood VE dropped to 95·7%, (CI 66·0‐99·4), the extra vaccinated controls made the age subgroup analysis statistically significant for all ages (Table 3). Vaccine effectives was 100% in those under 5 years (CI 62·8–100) and 91·7% in those 60 months and over (CI21·2–99·8%). In those under 3 years of age, VE was 100% (CI 11·4‐100), and in those 36 months and over it was 95·3% (CI 62·2–99·9).

Table 3.

Vaccine effectiveness comparisons (vaccinated = at least 10 days prior to disease)

| H1N1+ | H1N1− | Point estimate | Vaccine effectiveness (VE) 95% C I | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children 6–119 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 1 | 29 | P < 0·0001, VE = 95·7% | 66·0–99·4% |

| Not vaccinated | 27 | 34 | ||

| Total | 28 | 63 | ||

| Children 6–59 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 0 | 13 | P = 0·002, VE = 100% | 62·8–100% |

| Not vaccinated | 18 | 22 | ||

| Total | 18 | 35 | ||

| Children 60–119 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 1 | 16 | P = 0·01, VE = 91·7% | 21·2–99·8% |

| Not vaccinated | 9 | 12 | ||

| Total | 10 | 28 | ||

| Children 6–35 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 0 | 10 | P < 0·05, VE = 100% | 11·4–100% |

| Not vaccinated | 9 | 18 | ||

| Total | 9 | 28 | ||

| Children 36–119 months | ||||

| Vaccinated | 1 | 19 | P < 0·001, VE = 95·3% | 62·2–99·9% |

| Not vaccinated | 18 | 16 | ||

| Total | 19 | 35 | ||

*Fisher’s exact one‐sided test statistic used as an expected cell size <5 present. Other estimate chi‐square.

As there was now a vaccinated case in the secondary analysis, multivariate analysis was possible. Step wise addition of pandemic vaccine receipt, age as a binary variable (<36 months as with the policy for second doses), gender, pre‐existing medical conditions, First Nations ethnicity, receipt of seasonal vaccine, and hospitalization had no significant impact on VE data. Only the receipt of pandemic vaccine was significant in multivariate analysis, irrespective of the model. In no model was the odds ratio point estimate for pandemic vaccine greater than 0·06 (equivalent to a VE of 94%). The full model is shown in Table 4 with a VE of 96·3% (CI 69·8–99·5).

Discussion

Recently, ongoing studies in children of the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of Arepanrix™ vaccine identified increased fever and increased local and systemic reactions when a second dose was given albeit with an increase in immune response. This led to a warning by the European Medicines Agency 7 and an updated policy position by the United Kingdom Joint Committee of Vaccination and Immunisation 8 recommending a single 0·25‐ml dose for all children other than the immunosuppressed.

National vaccine policy recommendations, even with the same formulation, have been inconsistent reflecting the minimal available data on immunogenicity and efficacy. The Swedish Medical Products Agency continues to recommend two half doses of vaccine despite increased fever. In Germany, a statement from the Paul Ehrlich Institute suggests a single dose as appropriate for all age groups because of the increased reactogenicity. The Canadian vaccination policy at the time of this review was to give a second dose to children 6 months to 35 months of age and to those children 3–9 years with a chronic medical condition.

The relative absence of the first wave of the pandemic in New Brunswick with only three hospitalized cases meant that few children carried immunity from the previous wave, allowing a naive group to be assessed. Additionally, the arrival of the second wave of infections just after commencement of the vaccine campaign meant that few children were already immune prior to the study because of disease, thus minimizing this as a confounder in assessing effectiveness. Despite the low numbers available for the review, the statistically significant vaccine efficacy of 100% suggests that children <10 years are protected against laboratory‐confirmed influenza by a single dose of 0·25 ml Arepanrix™.

The significance remained in age subgroup analysis other than in those 6 months to 35 months when effective vaccination was defined as requiring 2 weeks post administration. Even in this age group, no vaccine failures were seen, and the lack of statistical significance was because of low numbers. As there were no vaccine failures, the impact of other confounders was not assessable in that analysis.

Eight children in the case category had received a dose of vaccine, and it was possible that the impact would reduce if a shorter time for effective vaccination was allocated. A repeat analysis was undertaken defining effective vaccination as occurring after only 10 days post administration. This analysis produced one vaccinated case but strengthened the statistical significance of all VE estimates. In multivariate analysis, only receipt of pandemic vaccine was significant and VE remained very high at 96%.

Only two children received a second dose of vaccine prior to symptom onset, and in both cases, the second dose was given only 1 day before. Hence, the high protection produced by a single dose cannot be attributed to the confounder of second doses in some children.

This review allocated controls using children with ILI who were influenza negative on laboratory testing. This use of a ‘test negative’ design for a community‐based study of influenza VE was modeled by Orenstein and found to provide a reliable estimate of the OR from a case–control study when a test with a high specificity is used. 9 The methodology is also consistent with the recommendations of the European CDC for vaccine efficacy studies. 10 Unfortunately, no data are available on local specificity; during the pandemic, laboratories were loathed to test negative specimens from other sources. The low numbers are a limitation of the review; vaccine coverage in children <10 years reached 80% in New Brunswick by early December, and no cases were seen in the month of December forcing the cessation of the review (see Figure 2).

Additionally, the sensitivity of the PCR test for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) is less than 100% and is dependent on timely and high‐quality specimen collection. In New Brunswick, some respiratory specimens were influenza A PCR positive but PCR negative for both seasonal (H1N1, H3N2) and pandemic (H1N1) strains. These specimens are thought to be probable H1N1 infections with viral loads too low to be detected by current pandemic virus PCR testing. However, none of these patients were children under 10 years, and so allocating these cases to the pandemic group did not affect data in either the case or control arm of the review.

At the time of the review, the recommended testing policy in New Brunswick was only to test those children with more severe disease or an underlying condition. It is possible thus that our findings represent protection against severe disease and not all laboratory‐confirmed infections. However, the large numbers of tests at the time in the community and the low proportion hospitalized (29%) suggest that a significant proportion was being tested without severe disease being present. Also, four children who had been tested were excluded as their symptoms were too mild to qualify as ILI, again suggesting that milder cases were being tested in family practice. To further examine the possibility that this finding was an artifact of protection against more severe disease, hospitalization was included as a potential confounder in the multivariate analysis but did not contribute significantly to variance.

There is also a possibility of bias in that physicians, aware of the vaccination status of children, may have been less ready to order H1N1 tests in those vaccinated. This is not likely to have been significant as 58% of the study population had received vaccine, similar to the average coverage during that period in New Brunswick.

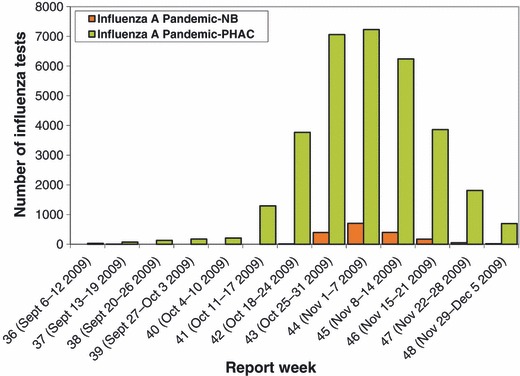

This high and increasing coverage appeared to have an effect on the epidemiology of the second wave that lasted just under 5 weeks in New Brunswick further adding to the likelihood that the effect seen is valid. The temporal relationship between disease numbers and childhood vaccination is shown in Figure 2. Additionally, the pandemic, despite starting later in New Brunswick, ended earlier than in Canada overall (Figure 3). Much lower coverages were seen on the West Coast of Canada and in the prairie provinces. The positive impact of vaccinating children on herd immunity has been described elsewhere in Canada. 11

Figure 3.

Comparison of epidemiological curve for Canada and New Brunswick.

The peak notification rates in New Brunswick, during the 3 weeks of highest activity in the second pandemic wave, were significantly higher than for Canada overall being 57·5, 93·8 and 52·7/100 000 compared to Canadian rates of 20·9, 21·4, and 18·5/100 000. This suggests that the change in the epidemic curve during the second wave in New Brunswick was not related to low activity in the province again.

Despite the potential limitations of the study, the lack of any documented vaccine failure suggests that the reported increased reactogenicity of second doses could safely be avoided by having a single dose vaccine policy if an adjuvanted vaccine of this type is used.

A recent German study of VE, using the screening method 12 with the same adjuvanted vaccine, 13 found very similar results in adults. Vaccine efficacy in this review was estimated at 96·8% (95%CI 95·2–97·9) for all persons aged 14–59 years, dropping slightly to 83·3% (95%CI 71·0–90·5) for persons 60 years or older, again adding weight to the New Brunswick findings. The effectiveness of this vaccine gives hope that a new generation of seasonal influenza vaccines may be developed with improved capacity to protect children against the significant morbidity associated with influenza each year.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the study protocol. P Van Buynder, J Dhaliwal, J Van Buynder, and FW Tremblay were involved in the analysis of the data and led the writing of the manuscript. M Minville‐LeBlanc, J Van Buynder, and C Couturier managed the data collection. R Garceau managed the diagnostic processes and authored this component of the methods. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version that was submitted.

Acknowledgements

We thank the research assistants who helped recruit children for the review as well as the participants’ parents. We particularly acknowledge the assistance of Rebecca, Clark‐Wright, and Jackie Badcock. We also thank John Hoey for critical appraisal of the manuscript and BaoGang Fei and Bin Zhang for statistical assistance.

References

- 1. Baker MG, Kelly H, Wilson N Pandemic H1N1 influenza lessons from the southern hemisphere. Euro Surveill 2009;14(42): pii=19370. Available online: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. New South Wales public health network . Progression and impact of the first winter wave of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza in New South Wales, Australia. Euro Surveill 2009;14(42):pii=19365. Available online: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith S, Demicheli V, Di Pietrantonj C et al. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD004879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. http://www.gsk‐clinicalstudyregister.com/files/pdf/27868.pdf .

- 5. http://www.gsk.ca/english/docs‐pdf/Arepanrix_PIL_CAPA01v01.pdf .

- 6. Fouchier RAM, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S et al Detection of Influenza A viruses from different species by PCR amplification of conserved sequences in the matrix gene. J Clin Microbiol 2000; 38(11):4096–4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/general/direct/pr/78440409en.pdf .

- 8. http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/hss‐md‐58‐2009.pdf .

- 9. Orenstein EW, De Serres G, Haber MJ et al. Methodological issues regarding the use of three observational study designs to assess influenza vaccine effectiveness. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36:623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/0907_TED_Influenza_AH1N1_Measuring_Influenza_Vaccine_Effectiveness_Protocol_Case_Control_Studies.pdf .

- 11. Loeb M, Russell ML, Moss L et al. Effect of influenza vaccination of children on infection rates in Hutterite communities. JAMA 2010; 303(10):943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farrington CP. Estimation of vaccine effectiveness using the screening method. Int J Epidemiol 1993; 22(4):742–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wichmann O, Stocker P, Poggensee G et al. Pandemic Influenza A(H1N1) 2009 breakthrough infections and estimates of vaccine effectiveness in Germany 2009‐2010. Euro Surveill 2010;15(18): pii=19561. Available online:http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?Articleld=19561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]