Abstract

Please cite this paper as: Wada et al. (2010). An epidemiological analysis of severe cases of the influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in Japan. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 4(4), 179–186.

Background The age distribution of confirmed cases with influenza A (H1N1) 2009 has shifted toward children and young adults, in contrast to interpandemic influenza, because of the age specificities in immunological reactions and transmission characteristics.

Objectives Descriptive epidemiological analysis of severe cases in Japan was carried out to characterize the pandemic’s impact and clinical features.

Methods First, demographic characteristics of hospitalized cases (n = 12 923), severe cases (n = 894) and fatal cases (n = 116) were examined. Second, individual records of the first 120 severe cases, including 23 deaths, were analyzed to examine potential associations of influenza death with demographic variables, medical treatment and underlying conditions. Among severe cases, we compared proportions of specific characteristics of survivors with those of fatal cases to identify predictors of death.

Results Age distribution of hospitalized cases shifted toward those aged <20 years; this was also the case for deaths without underlying medical conditions. Deaths in adults were mainly seen among those with underlying medical conditions, resulting in an increased risk of death as a function of age. According to individual records, the time from onset to death in Japan appeared rather short compared with that in other countries.

Conclusion The age specificity of severe cases and their underlying medical conditions were consistent with other countries. To identify predictors of death in influenza A (H1N1) 2009 patients, more detailed clinical characteristics need to be examined according to different age groups and types of manifestations, which should ideally include mild cases as subjects.

Keywords: Critical illness, encephalitis, H1N1, influenza, pandemic, respiratory failure

Introduction

Japan identified its first case of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection on 9 May 2009, and its incidence has increased steadily until it hit the first peak in November 2009. 1 The unique antigenic features of the virus, the age specificity of transmission (e.g., age‐specific contact frequency) and age‐dependent immune reactions are thought to have resulted in a high incidence among young adults – an epidemiological profile that is different from interpandemic influenza. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 These characteristics led to a surge in pediatric patients. Severe cases have also been seen among adults, especially among those with underlying medical conditions. 9 , 10

To minimize the potential number of deaths attributed to this disease, it is critically important to clarify the epidemiological and clinical features of severe cases, both at individual and at population levels. The purpose of this study is to summarize the epidemiological characteristics of severe cases of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 in Japan, measuring the pandemic impact and describing the clinical features.

Methods

Data and case definition

Our study was composed of two parts. First, we presented epidemiological characteristics of severe cases using the most recent summary statistics (as of 15 December 2009). Second, individual records by 6 October 2009 were analyzed in detail. Hereafter, cases in three different classifications of severity – hospitalized cases, severe cases and critically ill cases – were analyzed. All of these cases were mandatorily reported to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan, through local public health offices.

We conducted the following analysis to comply with the research demands of the MHLW. Hospitalized cases refer to those who were admitted to hospital as a result of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection including confirmed cases (i.e., diagnosed by means of RT‐PCR) and probable cases (i.e., those with influenza‐like illness who tested positive for influenza A by means of rapid diagnostic testing or with an epidemiological link to a probable or a confirmed case). Until 19 June 2009, all suspected cases had been advised to be admitted to, and monitored at, hospital; thereafter, the Japanese government ceased its isolation policy targeting all cases (i.e. switching their control policy from containment to mitigation). The surveillance of hospital admissions started from 24 July 2009 and thus does not include apparently mild cases, who tended to be admitted during the very early stage of the 2009 pandemic.

Severe cases were defined as confirmed or probable cases who met one of the following conditions: patients who (i) were diagnosed with influenza‐associated encephalopathy; (ii) were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU); (iii) were intubated; or (iv) died. Among these, influenza‐associated encephalopathy was defined as those showing clinical symptoms or signs suggestive of acute encephalopathy. These signs and symptoms included altered consciousness (e.g., delirium, confusion and cognitive impairment) and loss of consciousness (e.g., deep coma, coma, semicoma, stupor and somnolence) persisting for longer than 24 h. Cases with meningitis, myelitis and febrile convulsions, without prolonged unconsciousness, were excluded from the influenza‐associated encephalopathy. Critically ill cases referred to severe cases excluding influenza‐associated encephalopathy. Consequently, critically ill cases represent a portion of severe cases; we used these two definitions of cases with some overlaps, because influenza‐associated encephalopathy might potentially be milder than other severe cases. All the severe cases included in our second part of analysis (i.e., analysis of individual records) were confirmed by means of RT‐PCR, except for three fatal probable cases (which had positive results from rapid diagnostic testing).

Statistical analysis

First, the summary statistics of the above‐mentioned classifications of cases, reported by 15 December 2009, were analyzed. Descriptive epidemiological features of hospitalized cases, severe cases and deaths were summarized – especially age specificity. It should be noted that deaths were mostly included among severe cases (except for those who had not been diagnosed prior to their deaths), and the severe cases were included among hospitalized cases; we analyzed the multiple layers of cases to estimate the age‐specific risk of fatal outcome and severe manifestations among severe and hospitalized cases, respectively. Because the age distribution of ICU admissions was not consistently stratified by age group, severe cases in the first part of analysis included those who were intubated and/or diagnosed as influenza‐associated encephalopathy. Because the original data obtained from the MHLW were given as summary statistics in discrete age groups, we compared age distributions between different groups by the chi‐square test. To measure the impact of the pandemic in Japan and to explore the potential role of age in determining its clinical course, we examined age‐specific ratio of deaths to hospitalizations (here, we used the term ‘ratio’ rather than ‘proportion,’ because not all fatal cases were reported as hospitalized cases prior to their death event). The ratios of those intubated to hospitalizations and cases of influenza‐associated encephalopathy to hospitalizations were also examined by age group. Subsequently, age‐specific hospitalization and death rates per population were also examined to estimate the impact of the pandemic at the population level.

Second, to summarize clinical characteristics of severe and critically ill cases, we analyzed individual records of a total of 120 severe cases, including 23 deaths, of patients who developed the disease by 6 October 2009. We investigated potential associations of influenza death with the following variables, seeking potential predictors of death among severe cases: age, gender, time from onset to admission, antiviral treatment, ICU admission, intubation and specific underlying conditions. The times of illness onset, first antiviral treatment and hospital admission were reported as daily data (i.e., only the dates of these events were known); we calculated the time intervals between two events as difference between the two dates plus 1. These demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed by stratifying severe cases into four sub‐categories: (i) those aged <18 years with influenza‐associated encephalopathy, (ii) other patients aged <18 years, (iii) patients aged from 18 to 64 years, and (iv) patients 65 years and older. The time from onset to hospitalization was modeled as a continuous variable, while all the remaining variables were dealt as dichotomous variables. We used three cutoff values for antiviral treatment: 1, 2 and 3 days between onset of illness until antiviral treatment was started. When we examined the influence of time from onset to hospitalization on the risk of death, we compared the distribution between those who survived and those who died by means of the non‐parametric Wilcoxon test. For the remaining hypothesis testing, Fisher’s exact test (two‐sided) was employed, comparing the proportion of those with a specific dichotomous factor between those survived and died. The level of statistical significance was set at P = 0·05.

Results

Pandemic impact in Japan

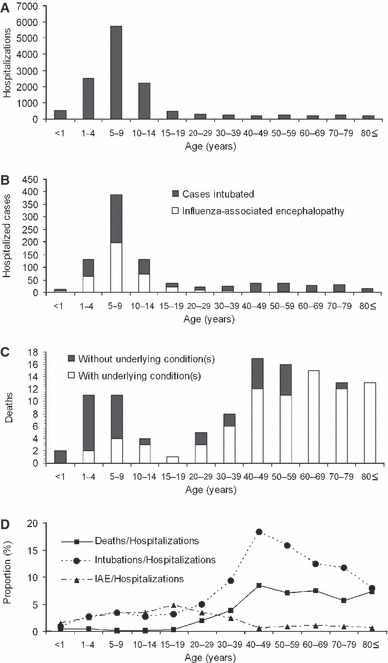

Figure 1(A–C) shows the age distributions of the cumulative numbers of hospitalized, severe and fatal cases. As of 15 December 2009, 12 923 hospitalizations were reported, among which 508 cases were intubated owing to respiratory failure and 386 cases were diagnosed as influenza‐associated encephalopathy. Hospitalized cases were most frequently seen among those aged <20 years; the mean [standard deviation (SD)] and median ages were 12·9 (16·8) and 7·5 years, respectively. Men accounted for 63·7% (n = 8229) of the total. Of the 12923 hospitalized cases, 4567 (35·3%) were reported as having at least one underlying condition. Four major underlying conditions were frequently reported; i.e., chronic cardiovascular disease (n = 234, 1·8%), chronic renal disease (n = 174, 1·3%), chronic respiratory disease (n = 2961, 22·9%) and diabetes (n = 206, 1·6%). Only 41 cases (0·3%) were pregnant women. Mean (SD) and median ages of intubated cases were 23·8 (24·8) and 7·5 years, respectively, while those of influenza‐associated encephalopathy cases were 10·0 (9·9) and 7·5 years, respectively. The intubated cases appeared to be significantly older than those with influenza‐associated encephalopathy (P < 0·01).

Figure 1.

Age distribution of hospitalized cases, severe cases and deaths with influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in Japan. Panels A–C show the cumulative numbers as of 15 December 2009. (A) Hospitalizations (n = 12 923). (B) Cases intubated (n = 508) or with influenza‐associated encephalopathy (n = 386). (C) Deaths stratified by those with (n = 82) and without (n = 34) underlying condition. (D) Age‐specific proportions of intubated cases, cases with influenza‐associated encephalopathy and deaths among hospitalized cases. IAE, Influenza‐associated encephalopathy.

As of 15 December 2009, 116 deaths have been reported. The ratio of deaths to hospitalizations for the entire sample population was 0·89% (i.e., 1:112). Unlike hospitalized and severe cases, the age distribution of fatal cases revealed two peaks, one among children aged <10 years and another among adults aged 40–49 years (Figure 1C). The mean (SD) and median ages were 45·5 (27·5) and 45·0 years, respectively. Men accounted for 59·5% (n = 69). Figure 1(C) stratifies fatal cases by presence or absence of any one underlying condition. Whereas the mean (SD) and median ages of fatal cases without underlying conditions were 23·0 (22·8) and 7·5 years, respectively, the mean (SD) and median ages of fatal cases with at least one underlying condition were 54·9 (23·7) and 55·0 years, respectively. Fatal cases with at least one underlying condition were significantly older than those with no underlying condition (P < 0·01). It is worth noting that 40 out of a total of 41 deaths for those aged 60 years and older had at least one underlying medical condition.

Figure 1(D) shows the ratios of deaths to hospitalizations, intubated cases to hospitalizations and influenza‐associated encephalopathy cases to hospitalizations as a function of age. The proportions of intubated cases and influenza‐associated encephalopathy cases among the total of hospitalized cases were 3·9% and 3·0%, respectively. The age‐specific proportions of intubated patients and deaths among hospitalized cases tend to increase as a function of age, with a peak around those aged 40–49 years. The proportion of influenza‐associated encephalopathy cases among hospitalized cases peaked in those aged 15–19 years, with decreasing frequency in older age groups.

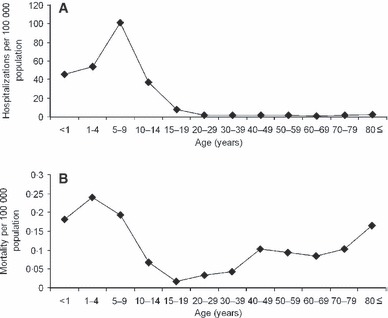

Figure 2 shows the age‐specific hospitalization rate and mortality rate per population. For the entire Japanese population, the hospitalization rate was estimated at 10·1 per 100 000 population. Similarly, the mortality rate was estimated at 0·1 per 100 000 population. The risk of hospitalizations at the population level was highest among those aged 5–9 years (Figure 2A), reflecting the highest number of hospitalized cases in Figure 1(A). Although the age‐specific patterns of mortality rate also reflected that of the absolute numbers of deaths in Figure 1(C), children aged from 1 to 4 years yielded the highest mortality estimate (0·24 per 100 000). Especially, it should be noted that pediatric mortality rate among those aged below 10 years appeared to be higher than that among elderly (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Age‐specific hospitalization rate and death rate with influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in Japan. (A) Age‐specific hospitalization rate per 100 000 population. (B) Age‐specific mortality rate per 100 000 population. These figures used cumulative numbers of hospitalizations and deaths as of 15 December 2009; estimates throughout the entire course of the pandemic wave are therefore expected to be larger. It should also be noted that those cumulative numbers represent only diagnosed cases and substantial number of undiagnosed cases are not included.

Analysis of first 120 severe cases

Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics for the four sub‐categories of severe cases. Of the first 120 severe cases whose individual records were available, those aged <18 years accounted for 71·7%. All 11 cases aged 65 years and older resulted in death, while the proportion of deaths among cases aged <18 years and those from 18 to 64 years was smaller (5·3% and 34·8%, respectively). The median age of fatal cases was 57 years and included 13 men and 10 women (Table 2). Men accounted for 63·3% (n = 76) of the total severe cases and 56·5% (n = 13) of total deaths; there was no gender specificity in the risk of death among severe cases (P = 0·53; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of severe cases with confirmed or probable diagnoses of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in Japan

| Characteristic | Aged <18 years with influenza‐associated encephalopathy | Other cases aged <18 years* | Those aged 18–64 years | Those aged 65 years and older |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 48 (with 3 deaths) | n = 38 (with 1 death) | n = 23 (with 8 deaths) | n = 11 (with 11 deaths) | |

| Total (deaths) | Total (deaths) | Total (deaths) | Total (deaths) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 17 (0) | 11 (0) | 10 (4) | 6 (6) |

| Mean time from onset to hospitalization (days) | 2·4 (2·0) | 2·4 (2·0) | 3·6 (3·3) | 3·2 (3·2) |

| Onset to death (days) | ||||

| Mean | (6·0) | (16·0) | (6·3) | (5·4) |

| Median | (5·0) | (16·0) | (4·5) | (4·0) |

| Antiviral treatment† | ||||

| ≤1 day | 12 (0) | 8 (0) | 4 (0) | 5 (5) |

| ≤2 days | 34 (3) | 26 (0) | 8 (1) | 7 (7) |

| ≤3 days | 42 (3) | 32 (0) | 9 (2) | 8 (8) |

| Admission to intensive care unit (ICU)‡ | 11 (3) | 29 (1) | 17 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Intubation | 8 (3) | 31 (1) | 15 (4) | 3 (3) |

*Cases aged below 18 years reported as severe for reasons other than influenza‐associated encephalopathy.

†Time from illness onset to antiviral treatment.

‡Admitted to an intensive care unit at least once during the course of disease. It should be noted that ICU admission and intubation were the criteria to be reported as severe cases.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the first 23 fatal cases of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in Japan (as of 6 October 2009)

| ID | Sex | Age group (years)* | Any documented comorbidity | Time from onset to death (days) | Time from hospitalization to death (days) | Antiviral treatment within 48 h after onset | Intensive care unit admission | Intubation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 50–59 | Yes | 7 | 4 | No | Yes | No |

| 2 | Female | 80–89 | Yes | 7 | 7 | Unknown | No | Yes |

| 3 | Male | 70–79 | Yes | 3 | 2 | Yes | No | No |

| 4 | Male | 30–39 | Yes | 8 | 3 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Female | 70–79 | Yes | 1 | 1 | Unknown | No | No |

| 6 | Male | 60–69 | Yes | 9 | 6 | Yes | Yes | No |

| 7 | Female | 20–29 | Yes | 21 | 21 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Female | 30–39 | Yes | 3 | 1 | Yes | No | No |

| 9 | Female | 60–69 | Yes | 3 | 2 | Yes | No | Yes |

| 10 | Female | 40–49 | Yes | 2 | 1 | Unknown | No | No |

| 11 | Male | 70–79 | Yes | 4 | 4 | No | No | No |

| 12 | Male | 10–19 | Yes | 16 | 15 | Unknown | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Male | 90–99 | Yes | 4 | 4 | Yes | No | No |

| 14 | Male | 40–49 | Yes | 5 | 1 | No | No | No |

| 15 | Male | 90–99 | Yes | 4 | 1 | Yes | No | No |

| 16 | Female | 60–69 | Yes | 9 | 9 | Yes | Yes | No |

| 17 | Female | 70–79 | Yes | 11 | 9 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Female | 60–69 | No | 4 | 1 | Yes | No | No |

| 19 | Male | 0–9 | Yes | 3 | 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 20 | Male | 40–49 | Yes | 10 | 10 | Unknown | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | Female | 40–49 | No | 9 | 5 | No | No | Yes |

| 22 | Male | 0–9 | No | 5 | 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 23 | Male | 0–9 | No | 10 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

*Age is given in discrete 10‐year intervals as privacy protection for the limited number of severe cases in Japan.

Of the 120 severe cases, 57 (47·5%) had at least one underlying medical condition (Table 3). Of the 86 cases aged <18 years, 27 (31·4%) had one or more comorbidity, with asthma being the most common (22·9%). Similarly, of the 34 cases aged 18 years or older, 30 (88·2%) had comorbidities, and chronic respiratory disease (23·5%) was the most common. We did not find any underlying conditions that would significantly predict death among the severe or critically ill cases. Pregnant women were not seen in the first 120 severe cases.

Table 3.

Underlying medical conditions among severe cases with confirmed or probable diagnoses of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in Japan

| Medical condition | Aged <18 years with influenza‐associated encephalopathy | Other cases aged <18 years* | Those aged 18–64 years | Those aged 65 years and older |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 48 (with 3 deaths) | n = 38 (with 1 death) | n = 23 (with 8 deaths) | n = 11 (with 11 deaths) | |

| Total (deaths) | Total (deaths) | Total (deaths) | Total (deaths) | |

| Any one condition | 8 (1) | 19 (1) | 19 (6) | 11 (11) |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease* | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Chronic renal disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Chronic respiratory disease† | 5 (0) | 17 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (4) |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Hypertension | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Malignant neoplasm | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 4 (4) |

| Mental retardation or psychiatric disorder‡ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Neurological disease§ | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Obesity | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

*Any documented cardiovascular disease except for hypertension.

†Patients with asthma, emphysema or chronic bronchitis. Among 22 patients under 18 years of age, 21 had asthma. Among eight patients aged 18 years and older, four had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; e.g., chronic bronchitis or emphysema), 1 had both asthma and COPD and 3 had asthma only.

‡Any documented mental retardation or psychiatric disorder, the causes of which included cerebral palsy, Down’s syndrome, epilepsy and schizophrenia.

§Any documented cerebrovascular disease or congenital anomaly in the central nervous system.

The mean (SD) and median times from onset to hospitalization among severe cases were 2·6 (1·7) and 2·0 days, respectively (Table 1). The mean (SD) and median times from onset to death for the 23 fatal cases were 6·7 (4·9) and 5·0 days, respectively.

The timing of antiviral administration did not appear to significantly affect the clinical course (i.e., the risk of death) among either those with influenza‐associated encephalopathy or critically ill cases (P > 0·05 for all groups; Table 1). Among the cases with influenza‐associated encephalopathy (n = 48), 11 received treatment with zanamivir alone, 8 with zanamivir and oseltamivir, 28 with oseltamivir alone and 1 with no antiviral medication. Unfortunately, the route of administration and the time delay from illness onset to medication were not consistently recorded. There was no fatality among those who received treatment with zanamivir, and the only one case among 11 using zanamivir alone had asthma as the underlying medical condition (the remaining 10 cases did not have specific underlying conditions). Among critically ill cases aged <18 years (n = 38), two received treatment with zanamivir alone, four with a combination of zanamivir and oseltamivir, 30 cases with oseltamivir alone and two with no antiviral medication. The one fatality in this category was seen in a patient with asthma without antiviral treatment whose RT‐PCR positive result was only noticed 12 days after onset of illness. All the critically ill cases aged 18 years and older received treatment with oseltamivir except four individuals without medication. The four cases without medication resulted in death. Three fatal cases with influenza‐associated encephalopathy were admitted to ICU and intubated. Of 11 deaths among elderly, 8 (72·7%) received antiviral treatment within 3 days of illness onset (Table 1). The major causes of death for the eight deaths included exacerbation of underlying disease (n = 2), acute respiratory distress syndrome (n = 2) and pneumonia (n = 2).

Discussion

This study analyzed severe cases of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 reported to the MHLW of Japan, reviewing the demographic characteristics of cases by examining summary statistics of the national surveillance data and exploring the risk of death among first 120 severe cases whose individual records were available. Whereas the age distribution of hospitalized cases shifted toward those aged <20 years, the distribution of deaths showed two distinct peaks, one among children <10 years of age and another among those aged 40–49 years. As a consequence, the proportion of deaths among hospitalized cases increased with age, an epidemiological pattern that is consistent with the age‐specific case fatality ratio among confirmed cases. 11 , 12 As an important underlying mechanism of the increased risk of death with age among hospitalized cases, those who died with underlying medical conditions tended to be significantly older than those without. The age‐specific mortality rate was highest among those aged <10 years.

Reviewing the findings from the summary statistics, we observed the following:(i) hospitalized cases were mainly seen among children and young adults, which might reflect age‐specific immunity to the novel influenza A (H1N1) virus and age‐dependent transmission characteristics 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ; (ii) a similar age specificity was also seen in deaths among those without underlying medical conditions; and (iii) adult deaths among hospitalized cases, especially in the elderly, were seen among those with underlying medical conditions. The proportion of pregnant hospitalized cases, whose risk of death is believed to be high, 13 , 14 was rather small in Japan; the underlying mechanism of this phenomenon, e.g., potential influence of the membership structure in households and early treatment of pregnant cases, should be explored in the future.

From the analysis of individual records, four important conclusions can be drawn. First, cases among those aged below 18 years were more frequently reported to be severe than cases in adults, a finding that is specifically different from interpandemic influenza. As more than half of the critically ill cases in the United States, Australia and New Zealand have been adults, our finding may be specific for the Japanese setting. 10 , 15 It is likely that this finding is partly associated with the definition of severe cases in this study, because a substantial number of influenza‐associated encephalopathy cases are included among those aged <18 years. As the epidemic progresses furthermore, the age composition of severe cases may change. Second, the clinical course of this disease appears to have been rapid after onset. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 In particular, the time from onset to death in Japan was rather short compared with those reported elsewhere, 17 , 18 , 20 indicating a critical need to start appropriate medical management shortly after illness onset. Third, approximately half of the cases were accompanied by at least one underlying condition; this proportion was particularly high among adults. The observed proportion of severe cases with at least one underlying condition was smaller among children compared with other countries, but the estimate among adults was consistent with the United States and Canada, 15 , 16 perhaps reflecting higher frequency of diagnosis for influenza‐associated encephalopathy cases among children in Japan. Fourth, although the timing of antiviral administration did not appear to significantly reduce the risk of death among severe cases, fatal outcomes were frequently seen among those without antiviral treatment. Nevertheless, we also found that 8 out of 11 deaths among those aged 65 years and older received antiviral treatment within 3 days of illness onset. The statistical power of this particular aspect of our study was limited because of small sample size. In addition, it should be noted that the sample population for this analysis involved only severe cases, including many individuals who might have been also treated at earlier clinical stages. Actual reduction in the risk of death owing to antiviral treatment should ideally be investigated by similar comparisons using severe and non‐severe cases as the sample population (i.e., our analysis was only able to examine severe cases). Also, the use of these antivirals for the treatment of influenza‐associated encephalopathy may not be efficacious. The insignificance of the timing of antiviral administration is therefore inconclusive; further studies need to be conducted. 21 , 22

To identify potential predictors of death with influenza A (H1N1) 2009, the clinical characteristics of critically ill patients must be examined systematically according to age group and type of severe manifestations in multiple settings. 9 , 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 20 , 23 As future subjects, analysis of severe cases with more detailed clinical criteria for inclusion (e.g., respiratory failure, mechanical ventilation and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome) would lead to identification of potential predictors of death or other clinical patterns and may benefit decision‐making in critical care settings. Because our study was based on the national surveillance data, our analysis was not able to delve into further clinical details. An epidemiological analysis of bacterial coinfection and exacerbation of chronic respiratory diseases (or other chronic diseases) as potential predictors of death will also give useful feedback to clinicians. Despite the number of subjects that should be explored, we believe our study at least satisfies the need to descriptively characterize the epidemiological and clinical features of hospitalized and severe cases in Japan.

Acknowledgements

KW and AK received Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan in 2009. The work of HN was supported by JST PRESTO program.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan . Pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Current Situation update. Tokyo: National Institute of Infectious Diseases, 2009. Available at: http://idsc.nih.go.jp/disease/swine_influenza_e/index.html) (Accessed on 22 December 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Cauchemez S et al. Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings. Science 2009; 324:1557–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nishiura H, Castillo‐Chavez C, Safan M, Chowell G. Transmission potential of the new influenza A (H1N1) virus and its age‐specificity in Japan. Euro Surveill 2009; 14:pii=19227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishiura H, Chowell G, Safan M, Castillo‐Chavez C. Pros and cons of estimating the reproduction number from early epidemic growth rate of influenza A (H1N1) 2009. Theor Biol Med Model 2010; 7:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishiura H. Travel and age of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. J Travel Med 2010; in press (DOI:10.1111/j.1708‐8305.2010.00418.x). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jain R, Goldman RD. Novel influenza A (H1N1): clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009; 25:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chowell G, Bertozzi SM, Colchero MA et al. Severe respiratory disease concurrent with the circulation of H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:674–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reichert T, Chowell G, Nishiura H, Christensen RA, McCullers JA. Does glycosylation as a modifier of Original Antigenic Sin explain the case age distribution and unusual toxicity in pandemic novel H1N1 influenza? BMC Infect Dis 2009; 10:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Novel Swine‐Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team , Dawood FS, Jain S et al. Emergence of a novel swine‐origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2605–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. ANZIC Influenza Investigators ; Webb SA, Pettilä V, et al. Critical care services and 2009 H1N1 influenza in Australia and New Zealand. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1925–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Echevarría‐Zuno S, Mejía‐Aranguré JM, Mar‐Obeso AJ et al. Infection and death from influenza A H1N1 virus in Mexico: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2009; 374:2072–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donaldson LJ, Rutter PD, Ellis BM et al. Mortality from pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in England: public health surveillance study. BMJ 2009; 339:b5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Satpathy HK, Lindsay M, Kawwass JF. Novel H1N1 virus infection and pregnancy. Postgrad Med 2009; 121:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet 2009; 374:451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM et al. Hospitalized Patients with 2009 H1N1 Influenza in the United States, April‐June 2009. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1935–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Pinto R et al. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA 2009; 302:1872–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garske T, Legrand J, Donnelly CA et al. Assessing the severity of the novel influenza A/H1N1 pandemic. BMJ 2009; 339:b2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nishiura H. The relationship between the cumulative numbers of cases and deaths reveals the confirmed case fatality ratio of a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus. Jpn J Infect Dis 2010; 63:154–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishiura H, Klinkenberg D, Roberts M, Heesterbeek JA. Early epidemiological assessment of the virulence of emerging infectious diseases: a case study of an influenza pandemic. PLoS ONE 2009; 4:e6852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perez‐Padilla R, De La Rosa‐Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S et al. Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine‐origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:680–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith JR, Ariano RE, Toovey S. The use of antiviral agents for the management of severe influenza. Crit Care Med 2010; 38:S1–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hartley DM, Nelson NP, Perencevich EN et al. Antiviral drugs for treatment of patients infected with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:1851–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Domínguez‐Cherit G, Lapinsky SE, Macias AE et al. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) in Mexico. JAMA 2009; 302:1880–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]