Abstract

Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome (TBRS; OMIM 615879), also known as the DNMT3A-overgrowth syndrome, is an overgrowth intellectual disability syndrome first described in 2014 with a report of 13 individuals with constitutive heterozygous DNMT3A variants. Here we have undertaken a detailed clinical study of 55 individuals with de novo DNMT3A variants, including the 13 previously reported individuals. An intellectual disability and overgrowth were reported in >80% of individuals with TBRS and were designated major clinical associations. Additional frequent clinical associations (reported in 20-80% individuals) included an evolving facial appearance with low-set, heavy, horizontal eyebrows and prominent upper central incisors; joint hypermobility (74%); obesity (weight ³2SD, 67%); hypotonia (54%); behavioural/psychiatric issues (most frequently autistic spectrum disorder, 51%); kyphoscoliosis (33%) and afebrile seizures (22%). One individual was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia in teenage years. Based upon the results from this study, we present our current management for individuals with TBRS

Keywords: DNMT3A, Tatton-Brown-Rahman, overgrowth, intellectual disability

Introduction

Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome (TBRS; OMIM 615879), also known as the DNMT3A-overgrowth syndrome, is an overgrowth intellectual disability (OGID) syndrome first described in 2014 with a report of 13 individuals with de novo heterozygous DNMT3A variants 1, 2. Subsequently, a further 22 individuals with TBRS have been reported 3– 9.

In this report we have undertaken a detailed clinical evaluation of 55 individuals with de novo DNMT3A variants, including the 13 individuals we first reported in 2014. We have expanded and clarified the TBRS phenotype, delineating major and frequent clinical associations, which has informed our management of individuals with this new OGID syndrome.

Methods

The study was approved by the London Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC MREC/01/2/44). Patients were identified through Clinical Genetics Services worldwide and written informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals and/or parents. Photographs, with accompanying written informed consent to publish, were requested from all participants and received from the families of 41 individuals. Detailed phenotype data were collected through a standardized clinical proforma, a DNMT3A specific clinical proforma and clinical review by one of the authors. Growth parameter standard deviations were calculated with reference to UK90 growth data 10.

The degree of intellectual disability was defined in relation to educational support as a child and living impairment as an adult:

-

-

an individual with a mild intellectual disability typically had delayed milestones but would attend a mainstream school with some support and live independently, with support, as an adult;

-

-

an individual with a moderate intellectual disability typically required high level support in a mainstream school or special educational needs schooling and would live with support as an adult;

-

-

an individual with a severe intellectual disability typically required special educational needs schooling, had limited speech, and would not live independently as an adult.

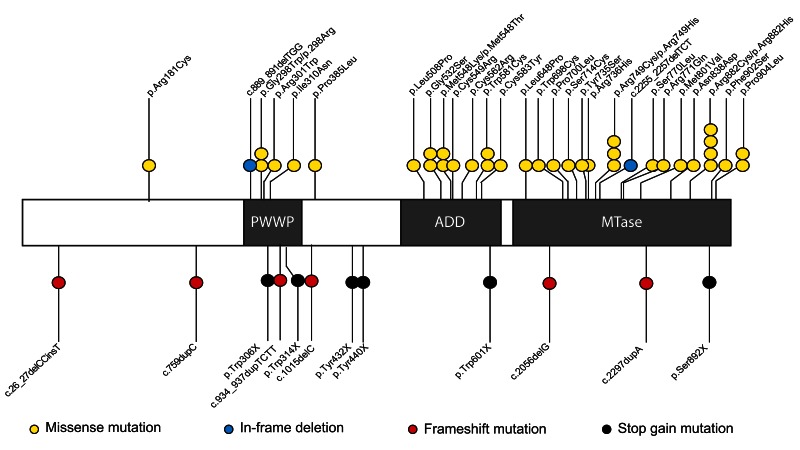

55 individuals were included with a range of de novo heterozygous DNMT3A variants: missense variants (36 individuals with 30 different variants); stop gain variants (six individuals); frameshift variants (six individuals); whole gene deletions (four individuals including identical twins (COG1961 and COG2006)); in-frame deletions (two individuals) and a splice site variant (one individual, Figure 1, Table 1). Computational tools predicted all 30 missense variants to be deleterious ( Mutation Taster2 and SIFT (version 6.2.1), Supplementary Table 1) and the splice site variant was predicted to disrupt normal splicing. Importantly, some of the variants are common in the general population due to age-related clonal haematopoiesis, limiting the utility of databases such as gnomAD in DNMT3A variant pathogenicity stratification ( Supplementary Table 1) 11, 12.

Figure 1. DNMT3A and the positions and types of variants with protein truncating variants shown below the protein (black and red lollipops) and missense variants and inframe deletions (yellow and blue lollipops) shown above the protein.

Whole gene deletions and the splice site variant are not shown on this figure. The three DNMT3A domains are shaded in grey: the proline-tryptophan-tryptophan-proline (PWWP) domain, the ATRX-Dnmt3-Dnmt3L (ADD) domain and the Methyltransferase (MTase) domain.

Table 1. Table of all individuals with TBRS and their associated phenotypes including growth and cognitive profiles.

| Case

number |

Variant type | Nucleotide

change |

Protein

change |

Inheritance | BW/

SD |

BHC/

SD |

BL/

SD |

Age/

yrs |

Ht/

SD |

HC/

SD |

Wt/

SD |

ID | Behavioural

issues |

Joint

hyper mobility |

Hypotonia | Kyphoscoliosis | Afebrile

seizures |

Other clinical issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG1849 | frameshift | c.26_27delinsT | de novo | 1.0 | nk | nk | 10.0 | 5.1 | nk | nk | mod | ASD | no | yes | no | yes | Multiple fungal and viral

infections, precocious puberty, leg length discrepancy |

|

| COG1919 | missense | c.541C>T | p.(Arg181Cys) | de novo | nk | nk | nk | 11.3 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 2.8 | mod | no | no | no | no | no | Pre-auricular skin tags, 5th

toe nail hypoplasia |

| COG2017 | frameshift | c.759dupC | de novo | -0.4 | nk | nk | 7.7 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 3.3 | mod | no | yes | yes | no | no | CAL macules, soft skin | |

| COG0274 | in-frame

deletion |

c.889_891delTGG | de novo | 3.3 | nk | 1.7 | 18.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 | nk | mod | no | nk | yes | no | yes | ||

| COG1843 | missense | c.892G>T | p.(Gly298Trp) | de novo | 1.6 | nk | 4.4 | 12.1 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 3.9 | mod | ASD, anxiety | yes | yes | no | no | Arachnoid cyst,

hypospadias |

| COG2008/

DDD260414 |

missense | c.892G>A | p.(Gly298Arg) | de novo | 2.1 | 2.8 | nk | 18.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.9 | mod | Anxiety | yes | no | yes | no | Myopia (-3D) |

| COG2019/

DDD293780 |

missense | c.901C>T | p.(Arg301Trp) | de novo | nk | nk | nk | 9.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.3 | mild | no | yes | no | no | no | |

| COG1963 | stop gain | c.918G>A | p.(Trp306X) | de novo | 1.5 | 1.2 | nk | 6.2 | 2.7 | 4.0 | 1.9 | sev | ASD,

regression |

nk | yes | no | yes | Seizures |

| COG1770 | missense | c.929T>A | p.(Ile310Asn) | de novo | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 10.3 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | sev | ASD,

compulsive eating |

yes | yes | yes | yes | Ventriculomegaly and

Chiari malformation, multiple renal cysts, multiple urinary tract infections, constipation, lumbar haemangioma |

| COG1670 | frameshift | c.934_937dupTCTT | de novo | 3.6 | nk | nk | 20.5 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.8 | sev | Temper

tantrums, aggressive, Psychosis (paranoid hallucinations) |

no | no | no | no | ||

| COG1962/

DDD271500 |

stop gain | c.941G>A | p.(Trp314X) | de novo | 0.7 | nk | nk | 5.0 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 2.2 | mod | no | no | no | no | no | |

| COG1974 | frameshift | c.1015delC | de novo | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 2.1 | mod | no | no | no | no | no | ||

| COG1998 | missense | c.1154C>T | p.(Pro385Leu) | de novo | -0.7 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 2.1 | mod | ASD | yes | yes | yes | no | |

| COG1916 | stop gain | c.1296C>G | p.(Tyr432X) | de novo | 2.9 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 21.0 | 3.9 | 0.6 | 3.2 | mod | ASD | yes | no | yes | no | AVNRT, mitral regurgitation,

pectus carinatum, amblyopia, photophobia |

| COG2007/

DDD294475 |

stop gain | c.1320G>A | p.(Trp440X) | de novo | 1.8 | nk | nk | 10.5 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 1.3 | mod | no | yes | no | no | no | Cryptorchidism |

| COG1925 | missense | c.1523T>C | p.(Leu508Pro) | de novo | 2.8 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 6.3 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.4 | mild | ASD | yes | yes | yes | no | Cryptorchidism |

| COG0141 | missense | c.1594G>A | p.(Gly532Ser) | de novo | 2.2 | nk | nk | 25.0 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 4.5 | mod | ASD | no | no | no | no | |

| COG1995 | missense | c.1594G>A | p.(Gly532Ser) | de novo | 3.9 | nk | nk | 22.0 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.0 | mild | ASD | yes | no | no | no | |

| COG0422 | missense | c.1643T>A | p.(Met548Lys) | de novo | 1.3 | 1.6 | nk | 15.3 | 1.4 | 3.4/12.8

yrs |

3.4 | sev | Aggression | yes | yes | no | no | Atrial septal defect |

| COG2009/

DDD282776 |

missense | c.1643T>C | p.(Met548Thr) | de novo | 1.7 | nk | nk | 15.3 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 1.9 | sev | ASD | yes | yes | no | yes | Umbilical hernia, early

puberty, cryptorchidism |

| COG1288 | missense | c.1645T>C | p.(Cys549Arg) | de novo | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 17.9 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 2.6 | mod | no | yes | yes | yes | no | Atrial septal defect, sagittal

craniosynostosis |

| COG2010/

DDD283406 |

missense | c.1684T>C | p.(Cys562Arg) | de novo | nk | nk | nk | 9.5 | 1.7 | 0.3/5.1yrs | 1.0/5.1yrs | mod | no | yes | no | no | no | Mild tonsillar ectopia |

| COG2003 | missense | c.1743G>C | p.(Trp581Cys) | de novo | -1.0 | nk | nk | 20.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | sev | no | yes | yes | no | yes | Cryptorchidism, lipoma,

hirsutism |

| COG2013/

DDD265343 |

missense | c.1743G>T | p.(Trp581Cys) | de novo | 0.7 | nk | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 1.4 | mod | no | yes | yes | no | yes | Chiari malformation and

ventriculomegaly, umbilical hernia |

| COG2002 | missense | c.1748G>A | p.(Cys583Tyr) | de novo | 2.5 | nk | 1.1 | 15.4 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | sev | regression | yes | yes | yes | yes | Seizures (tonic-clonic) |

| COG0510 | stop gain | c.1803G>A | p.(Trp601X) | de novo | 2.9 | nk | 1.5 | 18.8 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 4.1 | sev | obsessive | yes | no | no | no | Endochrondroma |

| COG1972 | splice site | c.1851+3G>C | de novo | 1.3 | nk | 1.7 | 6.6 | 4.0 | -1.2 | 3.1 | mod | no | yes | no | yes | no | Strabismus, myopia,

thyroid cyst |

|

| COG0553 | missense | c.1943T>C | p.(Leu648Pro) | de novo | -0.4 | nk | nk | 19.0 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 4.3 | mild | ASD | no | no | no | no | |

| COG2021 | frameshift | c.2056delG | de novo | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 10.0 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 0.7 | mild | no | nk | no | no | yes | Seizures | |

| COG1942 | missense | c.2094G>C | p.(Trp698Cys) | de novo | 0.4 | nk | nk | 21.0 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 1.4/18.9yrs | mod | ASD, severe

psychosis and bipolar disorder |

yes | yes | yes | no | Menorrhagia, severe

constipation |

| COG1688 | missense | c.2099C>T | p.(Pro700Leu) | de novo | 1.2 | nk | 0.4 | 15.4 | 2.6 | 3.3 | mod | ASD | yes | yes | yes | no | ||

| COG0316 | missense | c.2141C>G | p.(Ser714Cys) | de novo | 1.2 | nk | nk | 4.4 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 2.9 | sev | no | yes | yes | yes | no | Bilateral

hydroureteronephrosis and left ureteral ectasia, platelet disorder, thick skull vault and sclerosis of sutures |

| COG2004 | missense | c.2204A>C | p.(Tyr735Ser) | de novo | 1.6 | nk | nk | 20.0 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.5 | mild | no | no | no | no | no | AML-FAB type M4

diagnosed age 12 years |

| COG0447 | missense | c.2207G>A | p.(Arg736His) | de novo | 1.0 | nk | 0.6 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | mild | no | yes | no | no | no | |

| COG1695 | missense | c.2245C>T | p.(Arg749Cys) | de novo | 0.8 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 15.5 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 1.4 | mod | no | yes | no | yes | no | Vesico-ureteric reflux,

hypodontia |

| COG2005 | missense | c.2245C>T | p.(Arg749Cys) | de novo | -1.0 | nk | 0.4 | 23.0 | 0.5 | 2.7 | mod | ASD,

psychosis and schizophrenia |

yes | no | no | no | ||

| COG0108 | missense | c.2246G>A | p.(Arg749His) | de novo | 0.3 | nk | nk | 20.8 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 4.4 | mod | no | yes | yes | no | no | |

| COG1632/

DDD263319 |

in-frame

deletion |

c.2255_2257delTCT | de novo | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | nk | nk | nk | mod | no | nk | no | no | no | Tight achilles tendons | ||

| COG1512 | frameshift | c.2297dupA | de novo | 4.0 | 3.5 | nk | 13.3 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 1.9 | mod | no | yes | no | no | no | ||

| COG2011 | missense | c.2309C>T | p.(Ser770Leu) | de novo | 0.9 | nk | nk | 16.3 | 2.6 | -0.1 | 0.4 | mod | Bipolar

disorder |

yes | yes | yes | no | Aortic root enlargement

and mitral valve regurgitation, hyperthyroidism |

| COG1971 | missense | c.2312G>A | p.(Arg771Gln) | de novo | 1.2 | nk | nk | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.4/2.6yrs | 3.1 | mod | ASD | nk | yes | no | no | Keratosis pilaris |

| COG1964 | missense | c.2401A>G | p.(Met801Val) | de novo | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 8.8 | 2.1 | -0.2 | 2.0 | mod | regression | yes | nk | yes | yes | |

| COG1771 | missense | c.2512A>G | p.(Asn838Asp) | de novo | 0.8 | nk | 1.5 | nk | nk | nk | mild | no | yes | nk | yes | yes | Testicular atrophy | |

| COG1923 | missense | c.2644C>T | p.(Arg882Cys) | de novo | 3.0 | 4.4 | nk | 5.8 | -0.2 | 2.5 | 1.1 | mod | no | yes | yes | no | no | Hydrocephalus secondary

to neonatal intraventricular bleed, swallowing difficulties |

| COG1945 | missense | c.2644C>T | p.(Arg882Cys) | de novo | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 2.9 | mod | no | no | yes | no | no | Cryptorchidism, capillary

malformation, strabismus, bilateral inguinal herniae, ventriculomegaly |

| COG1999 | missense | c.2644C>T | p.(Arg882Cys) | de novo | 0.9 | nk | 2.0 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.2 | mod | no | yes | yes | no | no | Ventriculomegaly,

obstructive and central sleep apnoea, cryptorchidism |

|

| COG2012 | missense | c.2645G>A | p.(Arg882His) | de novo | 0.3 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.5 | -0.2 | -0.8 | -1.4 | mod | no | yes | yes | yes | no | Atrial septal defect, bifid

sternum, umbilical hernia |

| COG1760 | stop gain | c.2675C>A | p.(Ser892X) | de novo | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 12.9 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | mild | no | no | no | no | no | Pes planus |

| COG0109 | missense | c.2705T>C | p.(Phe902Ser) | de novo | 1.7 | nk | 2.0 | 21.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.7 | mod | ASD | yes | no | yes | no | Mitral and tricuspid

regurgitation, polycystic ovarian syndrome, myopia |

| COG1677 | missense | c.2711C>T | p.(Pro904Leu) | de novo | 0.7 | nk | 7.3 | 3.9 | -0.4 | 3.9 | mod | ASD | yes | yes | no | no | Gowers manoeuvre on

standing |

|

| COG1887 | missense | c.2711C>T | p.(Pro904Leu) | de novo | 1.8 | nk | 0.0 | 9.5 | -0.3 | 0.3 | -1.1 | mod | Anxiety and

ADHD |

yes | yes | yes | no | Mitral regurgitation, Chiari

malformation |

| COG1813 | gene del | de novo | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 23.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 4.0 | mod | no | yes | no | no | no | Double teeth, recurrent

infections, polycystic ovaries syndrome |

||

| COG1961 | gene del | de novo | -0.1 | nk | nk | 5.8 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 2.8 | mod | ASD | no | yes | no | no | Patent ductus arteriosus,

hirsutism |

||

| COG2006 | gene del | de novo | -1.1 | nk | nk | 5.8 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2.1 | mod | ASD | no | yes | no | no | Patent ductus arteriosus,

hirsutism |

||

| COG2014 | gene del | de novo | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 0.7/2.0yrs | 2.8 | mild | ASD,

regression |

no | no | no | yes | Recurrent ear infections,

subclinical seizures |

Abbreviations: nk, not known; ID, intellectual disability; CAL, café au lait; SD, standard deviation; gene del, whole gene deletion; BW, birth weight; BHC, birth head circumference; BL, birth length; Ht, height; Wt, weight; HC, head circumference; mod, moderate; sev, severe; ASD, autistic spectrum disorder; br MRI, brain magnetic resonance imaging; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; FAB, Franco-American-British; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AVNRT, atrio-ventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia

Results

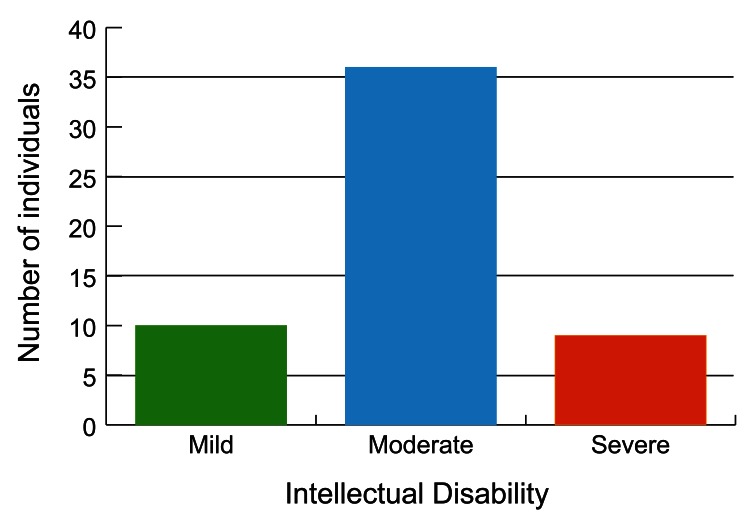

All 55 individuals had an intellectual disability: 18% had a mild intellectual disability (10/55); 65% had a moderate intellectual disability (36/55) and 16% had a severe intellectual disability (9/55) ( Table 1, Figure 2). Behavioural/psychiatric issues were reported in 51% (28/55) individuals and included combinations of autistic spectrum disorder (20 individuals); anxiety (three individuals); neurodevelopmental regression (four individuals two of whom regressed in teenage years); psychosis/schizophrenia (three individuals); aggressive outbursts (two individuals), and bipolar disorder (two individuals) ( Table 1).

Figure 2. Graph showing the range of intellectual disability in TBRS.

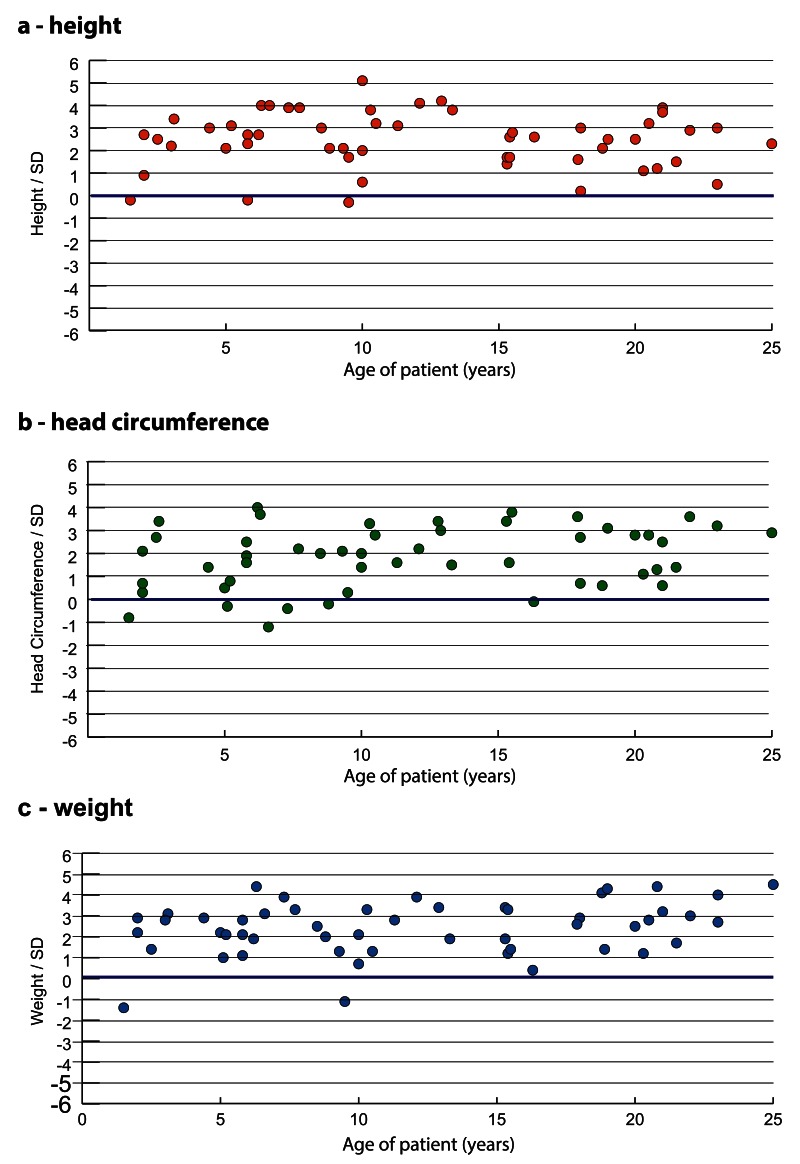

Postnatal overgrowth (defined as height and/or head circumference at least two standard deviations above the mean (≥2SD) 2, 13, was reported in 83% (44/53) individuals. Obesity, with a weight ≥2SD, was reported in 67% (34/51). The range of individual postnatal heights, head circumferences and weights is shown in Table 1 and Figure 3. The mean birth weight was 1.3SD with a range from -1.1 to 4.0 SD. We had limited data for birth head circumference and birth length, but their mean was 2.3SD and 1.6SD, respectively.

Figure 3.

Growth profile in individuals with TBRS a) height, b) head circumference and c) weight. The blue line represents the mean.

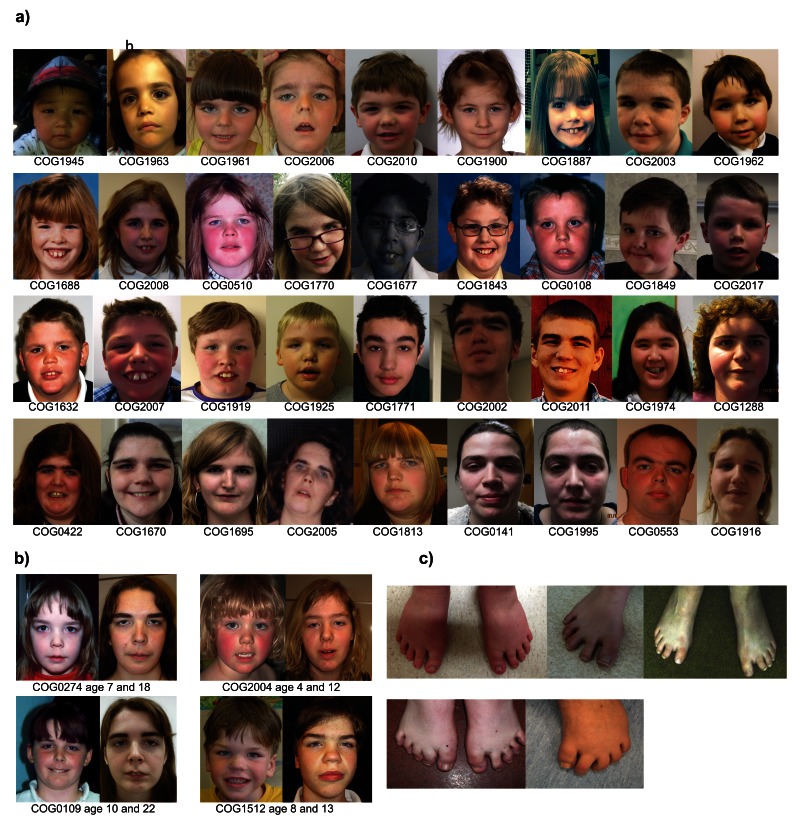

There were some shared, but subtle, facial characteristics often only becoming apparent in early adolescence ( Figure 4a and b). These included low-set, horizontal thick eyebrows; narrow palpebral fissures; coarse features and a round face. The two upper central incisors were also frequently enlarged and prominent.

Figure 4.

a) The facial appearance of children and adults with TBRS; b) the evolving facial appearance in four individuals with TBRS; and c) the characteristic short, widely spaced toes seen in TBRS.

Additional clinical features reported in greater than 20% (≥ 11) individuals included: joint hypermobility (74%, 37/50); hypotonia (54%, 28/52); kyphoscoliosis (33%, 18/55) and afebrile seizures (22%, 12/55) ( Table 1). In addition, short, widely spaced toes were frequently mentioned, but the overall frequency is unclear as we did not specifically ask about feet/toes on the clinical proforma ( Figure 4c).

Clinical features reported in at least two but fewer than 20% individuals included cryptorchidism (six individuals); ventriculomegaly (four individuals) and Chiari malformation (three individuals). In addition, a range of cardiac anomalies (including atrial septal defect, mitral/tricuspid valve incompetence, patent ductus arteriosus, aortic root enlargement and atrio-ventricular re-entry tachycardia) were reported in nine individuals. However, of note, two individuals with cardiac anomalies (patent ductus arteriosus, COG1961 and COG2006) were identical twins with DNMT3A whole gene deletions encompassing >40 genes. The patent ductus arteriosus in these individuals may, therefore, be attributable to twinning, alternative genes in the deleted region or the combined effect of a number of deleted genes.

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), AML-FAB (French-American-British classification) type M4, was diagnosed in one individual at the age of 12 years (COG2004). This individual had a de novo heterozygous c.2204A>C p.(Tyr735Ser) DNMT3A variant, identified in DNA obtained seven years prior to the diagnosis of AML.

Full clinical details from the 55 individuals are provided in Table 1.

Discussion

We have evaluated clinical data from 55 individuals with de novo constitutive DNMT3A variants to define the phenotype of TBRS. An intellectual disability (most frequently in the moderate range) and overgrowth (defined as height and/or head circumference ≥2SD above the mean) were reported in ≥80% of individuals and have been designated major clinical associations. Frequent clinical associations, reported in 20–80% of individuals with constitutive DNMT3A variants, included joint hypermobility, obesity, hypotonia, behavioural/psychiatric issues (most frequently autistic spectrum disorder), kyphoscoliosis and afebrile seizures. In addition, many individuals had a characteristic facial appearance although this may only be recognizable in adolescence.

TBRS overlaps clinically with other OGID syndromes including Sotos syndrome ( OMIM 117550), Weaver syndrome ( OMIM 277590), Malan syndrome ( OMIM 614753) and the OGID syndrome due to CHD8 gene variants 2. However, TBRS is more frequently associated with increased weight than the other OGID syndromes and may be distinguishable through recognition of the associated facial features, and absence of the facial gestalt of other OGID syndromes.

Somatic DNMT3A variants are known to drive the development of adult AML and myelodysplastic syndrome and over half of the DNMT3A somatic variants target a single residue, the p.Arg882 residue 14– 17. AML, diagnosed in childhood, has now been identified in two individuals with (likely) constitutive DNMT3A variants from a total of 77 (1/55 individuals in the current study and 1/22 previously reported individuals) 7. One of these individuals had a de novo c.2644CT p.(Arg882Cys) DNMT3A variant and developed AML at 15 years of age 7. The variant was present in genomic DNA extracted from the patient’s remission blood sample and skin fibroblasts. The second individual had a c.2204A>C p.(Tyr735Ser) DNMT3A variant identified in DNA obtained at 5 years of age and developed AML at the age of 12 years. Whilst these data indicate that AML may be a rare association of TBRS, currently the numbers of individuals reported with TBRS and AML are too few to either accurately quantify the risk of AML in TBRS or determine whether this risk is influenced by the underlying DNMT3A genotype. Further studies are required to address this.

The majority of individuals with TBRS are healthy and do not require intensive clinical follow up. However, our practice is to inform families and paediatricians of the possible TBRS complications of behavioural/psychiatric issues, kyphoscoliosis and afebrile seizures to introduce a low threshold for their investigation and/or management. In addition, we undertake a baseline echocardiogram at initial diagnosis to investigate cardiac anomalies detectable on ultrasound scan and frequently refer patients to physiotherapy to evaluate the degree of hypotonia and/or joint hypermobility and to determine whether targeted exercises may be beneficial. Finally, in the absence of evidence-based surveillance protocols for haematological malignancies, we advise clinical vigilance for symptoms possibly related to a haematological malignancy such as easy bruising, recurrent bleeding from gums or nosebleeds, persistent tiredness and recurrent infections.

Ethics and consent

The study was approved by the London Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC MREC/01/2/44).

Written informed consent was obtained from participants and/or parents for participation in the study (n=55) and publication of photographs of participants shown in Figure 4 (n=41).

Data availability

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and families for their active participation in this study and the clinicians that recruited them. The full list of collaborators is in Supplementary File 1. We also acknowledge the contribution Amanda Springer who helped in the recruitment of patient COG1945 and of the CAUSES Study whose investigators include: Shelin Adam, Christele Du Souich, Jane Gillis, Alison Elliott, Anna Lehman, Jill Mwenifumbo, Tanya Nelson, Clara Van Karnebeek, Sylvia Stockler, James O’Byrne and Jan Friedman. All are affiliated with the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. In addition, we would like to thank the DDD study for their collaboration.

Funding Statement

K.T.-B. is supported by funding from the Child Growth Foundation (GR01/13) and the Childhood Overgrowth Study is funded by the Wellcome Trust [100210]. The CAUSES Study is funded by Mining for Miracles, British Columbia Children’s Hospital Foundation and Genome British Columbia. The DDD study presents independent research commissioned by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund [HICF-1009-003], a parallel funding partnership between the Wellcome Trust and the Department of Health, and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute [098051]. The DDD study has UK Research Ethics Committee approval (10/H0305/83, granted by the Cambridge South REC, and GEN/284/12 granted by the Republic of Ireland REC). The research team acknowledges the support of the National Institute for Health Research, through the Comprehensive Clinical Research Network. This study makes use of DECIPHER (http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk), which is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 3 approved]

Supplementary material

Supplementary Table 1: Computational evaluation of DNMT3A missense variants.

.

Supplementary File 1: A full list of all the collaborators, study participants and the clinicians that recruited them, in this study.

.

References

- 1. Tatton-Brown K, Seal S, Ruark E, et al. : Mutations in the DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A cause an overgrowth syndrome with intellectual disability. Nat Genet. 2014;46(4):385–388. 10.1038/ng.2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tatton-Brown K, Loveday C, Yost S, et al. : Mutations in Epigenetic Regulation Genes Are a Major Cause of Overgrowth with Intellectual Disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(5):725–736. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okamoto N, Toribe Y, Shimojima K, et al. : Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome due to 2p23 microdeletion. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A(5):1339–1342. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tlemsani C, Luscan A, Leulliot N, et al. : SETD2 and DNMT3A screen in the Sotos-like syndrome French cohort. J Med Genet. 2016;53(11):743–751, pii: jmedgenet-2015-103638. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xin B, Cruz Marino T, Szekely J, et al. : Novel DNMT3A germline mutations are associated with inherited Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome. Clin Genet. 2017;91(4):623–628. 10.1111/cge.12878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kosaki R, Terashima H, Kubota M, et al. : Acute myeloid leukemia-associated DNMT3A p.Arg882His mutation in a patient with Tatton-Brown-Rahman overgrowth syndrome as a constitutional mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(1):250–253. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hollink IHIM, van den Ouweland AMW, Beverloo HB, et al. : Acute myeloid leukaemia in a case with Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome: the peculiar DNMT3A R882 mutation. J Med Genet. 2017;54(12):805–808. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lemire G, Gauthier J, Soucy JF, et al. : A case of familial transmission of the newly described DNMT3A-Overgrowth Syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(7):1887–1890. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen W, Heeley JM, Carlston CM, et al. : The spectrum of DNMT3A variants in Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome overlaps with that in hematologic malignancies. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(11):3022–3028. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woodcock HC, Read AW, Bower C, et al. : A matched cohort study of planned home and hospital births in Western Australia 1981-1987. Midwifery. 1994;10(3):125–135. 10.1016/0266-6138(94)90042-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. : Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488–2498. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Genovese G, Kahler AK, Handsaker RE, et al. : Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2477–2487. 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tatton-Brown K, Weksberg R: Molecular mechanisms of childhood overgrowth. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2013;163C(2):71–75. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, et al. : DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2424–2433. 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, et al. : Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(4):309–315. 10.1038/ng.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nikoloski G, van der Reijden BA, Jansen JH: Mutations in epigenetic regulators in myelodysplastic syndromes. Int J Hematol. 2012;95(1):8–16. 10.1007/s12185-011-0996-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abdel-Wahab O, Levine RL: Mutations in epigenetic modifiers in the pathogenesis and therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(18):3563–3572. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-451781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]