Abstract

Aim: Metastatic prostate cancer (mPCa) has a poor outcome with median survival of two to five years. The use of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is a gold standard in management of this stage. Aim of this study is to analyze the prognostic value of PSA kinetics of patient treated with hormonal therapy related to survival from several published studies

Method: Systematic review and meta-analysis was performed using literature searching in the electronic databases of MEDLINE, Science Direct, and Cochrane Library. Inclusion criteria were mPCa receiving ADT, a study analyzing Progression Free Survival (PFS), Overall Survival (OS), or Cancer Specific Survival (CSS) and prognostic factor of survival related to PSA kinetics (initial PSA, PSA nadir, and time to achieve nadir (TTN)). The exclusion criteria were metastatic castration resistant of prostate cancer (mCRPC) and non-metastatic disease. Generic inverse variance method was used to combine hazard ratio (HR) within the studies. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.2 and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: We found 873 citations throughout database searching with 17 studies were consistent with inclusion criteria. However, just 10 studies were analyzed in the quantitative analysis. Most of the studies had a good methodological quality based on Ottawa Scale. No significant association between initial PSA and PFS. In addition, there was no association between initial PSA and CSS/ OS. We found association of reduced PFS (HR 2.22; 95% CI 1.82 to 2.70) and OS/ CSS (HR 3.31; 95% CI 2.01-5.43) of patient with high PSA nadir. Shorter TTN was correlated with poor result of survival either PFS (HR 2.41; 95% CI 1.19 – 4.86) or CSS/ OS (HR 1.80; 95%CI 1.42 – 2.30)

Conclusion: Initial PSA before starting ADT do not associated with survival in mPCa. There is association of PSA nadir and TTN with survival

Keywords: androgen deprivation therapy, metastasis, PSA kinetics, prostate cancer, survival, systematic review, meta analysis

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer in men, and the fourth most common cancer worldwide. More than one million men worldwide were diagnosed with PCa in 2012 1. The incidence of local-regional PCa has increased since the introduction of prostate specific antigen (PSA). This circumstance reduces the incidence of metastatic PCa 2. PCa patient treated at early stages have a good prognosis with 5-year overall survival (OS) reaching 99%. In contrast, metastatic PCa patients generally experience a poor outcome. Several published studies showed a wide difference of survival, with median OS from two to five years 3– 5. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) becomes the standard treatment of patients with advanced PCa 6, 7, and with the first use reported by Huggins and Hodges in 1941 8.

In clinical practice, PSA is the most common diagnostic procedure to evaluate the disease and to predict the survival. PSA kinetics such as nadir PSA level, time to reach nadir (TTN), or specific PSA value after initiation of ADT might became a predictor of survival in several retrospective and clinical trial studies 5, 9– 11. Some limitations were shown in the previous report of investigation for PSA kinetic to survival. They included patients with heterogeneous backgrounds (such as metastatic disease prior to surgical or radiation therapy), and the sample size was small. Therefore, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the pooled effect of PSA kinetics of patient treated with hormonal therapy related to survival from several published studies.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The systematic review was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 12. All studies in English were included. Retrospective cohorts, prospective cohort, randomized clinical trial (RCT), were eligible for inclusion for this review. The inclusion criteria were that (i) the participant of the study had metastatic PCa; (ii) patients were treated with ADT either using orchiectomy or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist with or without anti-androgen (AA); (iii) the studies outcome were either progresion free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) or cancer specific survival (CSS); (iv) the studies had to analyze PSA kinetics (intial PSA prior to initiation of ADT, PSA nadir, and time to reach nadir (TTN) PSA). Studies analyzed in meta-analysis had to use adjusted analysis of prognostic factors, such as multivariate Cox regression, to overcome the confounding factors. Studies that analyzed patient with castration resistant PCa (CRPC) and non-metastatic disease were excluded.

Search strategy

Electronic searched were performed in three databases: MEDLINE, Science Direct, and Cochrane Library from 1950 to 2016. This literature searching was conducted in March 2017. Gray literature and conference abstract, especially from urology oncology conference, were also searched. References list from included article were reviewed. We used the following search strategy: (prostate cancer OR adenocarcinoma prostate), (survival OR prognosis OR prognostic), (metastasis OR metastases OR metastatic), (PSA OR “Prostate Specific Antigen” OR nadir OR “initial PSA” OR kinetic). Two researchers (A.A and A.R.A.H) were indecently assessing the title and abstract of the paper. They agreed the studies included in the meta-analysis. Disagreement between the two review authors on the selection of studies was resolved by discussion with third authors (C.A.M) as a senior investigator. We used EndNote X6 for screening of duplicated studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction table was created to extract data from each article. The data of study design, patient's characteristics, method of ADT, duration of follow up, outcomes of survival, and significant prognostic factors of PSA kinetics were collected from all included studies. For the observational studies, the quality of study was assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). There were three major components of this scale namely the selection of the group of the study, comparability, and assessment of the outcome. The quality of study assessed with number of stars based on NOS. A maximum 7 stars could be scored; 6 or 7 stars considered as high quality study, 4 – 5 stars corresponded with intermediate quality, and 0 – 3 stars showed low quality 13.

Synthesis of results

Meta-analysis was applied on studies with prognostic factor with similar outcome definition. I 2 test was conducted in order to evaluate the heterogeneity, whilst for >30% a random effects model was applied, or otherwise, fixed effects model was done. Confounding in the individual studies was estimated using Hazard Ratio (HR) adjusted estimation, thus generic inverse variance method was used. We only combined data to estimate pooled effect of categorical parameters due to feasibility of statistical analysis. Studies that evaluated parameters but could not synthesize to meta-analysis were describe quantitatively. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.2 from Cochrane Collaboration. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

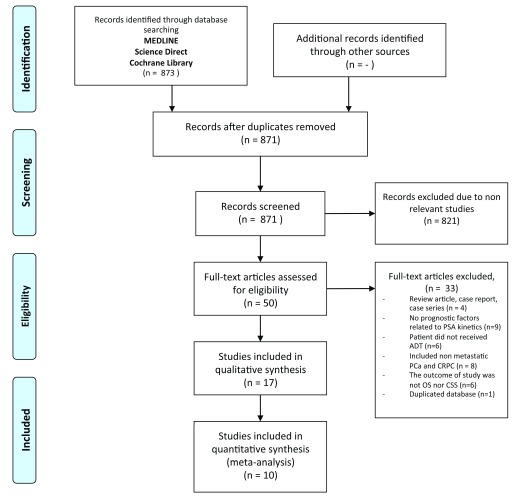

We found 873 citations throughout database searching. No additional records identified through searching from reference list of included studies. Seventeen studies were found to be consistent to the inclusion criteria of the study, but seven studies could not be evaluated the in meta-analysis ( Figure 1). Miyamoto et al. 14 did not published the hazard ratio, and put the cumulative survival rate as the outcome. Six other studies used numerical parameters of PSA kinetics that cannot combine in the forest plot 9, 15– 19. All of those studies were considered in qualitative synthesis. The characteristic of study is present in Table 1. Based on NOS, the quality of study included was good ( Table 2).

Figure 1. Flowchart showing the searching strategy of the studies.

Table 1. Characteristic of included studies.

| Study | Total

patient |

Androgen Deprivation

Therapy |

Follow - up time | Survival outcome | Significance Prognostic

Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bello 2017 25 | M1 = 79 | • Orchiectomy

• LHRH agonist |

NM | Median OS was 40.3 months | • NSAID use

• PSA nadir |

| Choueiri 2009 5 | M1 = 179 | • LHRH agonist with or

without AA • Orchiectomy |

Median follow up

48 months |

Median OS was 84 months | • GS

• TTN • PSA Nadir |

| Glass 2003 9 | M1 = 1,076 | Bilateral orchiectomy with

or without AA (flutamide) |

NM | Median OS was 32 months | • Initial PSA

• Presence appendicular bone disease • GS • Presence of bone pain • PS |

| Hong 2012 10 | M1 = 131 | CAB using LHRH agonist

plus AA |

Median follow up

30 months |

Median CSS

• PSA nadir < 2 ng/ml was 91.7 months • PSA nadir ≥ 2 ng/ml 49.8 |

• PSA nadir

• TTN |

| Hussain 2006 11 | M1 = 1,345 | CAB using LHRH agonist

(gosereline) plus AA (bicalutamide) |

Median follow up

was 38.0 months |

Median OS of PSA after

7 months ADT • ≤ 0.2 ng/ml was 75 months • 0.2 < PSA ≤ 0.2 ng/ml was 44 months • PSA > 4.0 ng/ml was 13 months |

• PSA after 7 months

of ADT • ECOG • Presence of bone pain • GS |

| Kadono Y, 2015 4 | M1a = 224,

M1b = 4386, M1c =278 |

• LHRH agonist with or

without AA • Orchiectomy |

Mean follow up

3.3 years |

The 5-year OS was

• 57.5% in M1a • 54.0% in M1b • 40.0% in M1c |

• GS

• PSA • Age |

| Kim KH, 2015 18 | M1 = 398 | • CAB (LHRH agonist

plus AA) |

Median follow up

44 months |

Median CSS was 65 months | • GS

• PSA nadir • TTN • PSA Half Life • N1 |

| Kimura, 2014 24 | M1 = 3006 | • Type of ADT was not

clear |

Median followed

up in young, middle and elderly group was 25.5, 35.3 and 38.5 months |

The 5-years OS

• Young age was 26.6% • Middle age was 59.7% • Elderly age was 55.3% |

• GS

• Concomitant bone and visceral metastasis • Age • Clinical T |

| Koo, 2014 17 | M1b = 248 | • Type of ADT was not

clear |

Median follow up

39.3 months |

Median CSS in PSA nadir

• < 0.2 ng/ml was 70 months • ≥ 0.2 ng/ml was 50 months |

• PSA nadir

• ALP • ECOG |

| Kwak 2002 23 | M1 = 145 | • LHRH agonist with or

without AA • Orchiectomy |

Median follow up

39 months |

Median survival of patients

with Nadir PSA (months) • < 0.2, = 53 • 0.2 to 1.0 = 42 • 1.1 to 10 = 24 • >10.1 = 15 |

• Nadir PSA |

| Miller 1992 25 | M1 = 48

patients |

• Orchiectomy

• LHRH agonist • Diethylatibestrol |

Median follow up

42 months |

Median PFS 19 months | • Nadir PSA |

| Miyamoto 14 | M1 – 94 | • LHRH agonist with AA | Median follow up

38.8 months |

5-yr OS rate 62.5% | • PSA

• Gleason Grade |

| Nayyar 2010 16 | M1 = 412 | • Surgical castration

• Medical castration • Antiandrogen |

Median follow up

55 months |

Median OS 5.7 years | • GS

• PSA doubling time |

| Park, 2009 15 | M1 = 131 | • LHRH agonist with or

without AA • Orchiectomy |

Median follow up

was 53.0 months |

Median CSS

• Short PSA doubling time was 35 months • Long PSA doubling time 95 months |

• High Nadir PSA

• Short PSA half time • Short PSA doubling time after nadir |

| Sasaki 2011 22 | M1 = 412 | • Bilateral orchiectomy

• LHRH agonist |

NM | Median OS 5.7 years | • PSA half time

• PSA doubling time • GS |

| Teoh 2017 21 | M1b = 419 | • LHRH agonist

• Bilateral orchiectomy |

Median follow up

was 48 months |

Median OS was 28 months | • PSA nadir ≥ 2 ng/ml

• TTN < 9.09 months |

| Tomiokoa 2014 20 | M1 = 236 | • LHRH agonist

• surgical castration • AA monotherapy • CAB |

Median follow up

47 months |

The 5-years OS was 63% | • Nadir PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/ml

• TTN < 6 month |

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; LHRH = luteinizing hormone releasing hormone; AA = anti androgen; CAB = combined anti androgen; PSA = prostate specific antigen; OS = overall survival; GS = Gleason score; TTN = time to nadir; NM = not mentioned; NSAID = non-steroidal anti inflammatory drug; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; PS = Performance Status; ALP = alkaline phosphatase; N1= regional nodal metastasis

Table 2. Methodological quality of the study based on NOS Scale.

| Study | Selection

(Max ****) |

Comparability

(Max **) |

Outcome

(Max ***) |

Total

Score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness

of exposed cohort |

Selection

of exposed cohort |

Ascertainment

of exposure |

No outcome

of interest at start |

Comparability of

cohorts on the basis of design of analysis |

Assessment

of outcome |

Was follow-up

long enough for outcomes to occur |

Adequacy of

follow up of cohorts |

||

| Bello 2017 25 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | Not clear | Not clear | 7 |

| Choueiri 2009 5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 |

| Glass 2003 9 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | Not clear | Not clear | 7 |

| Hong 2012 10 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Hussain 2006 11 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Kadono 2015 4 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Kim 2015 18 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Kimura 2014 24 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 |

| Koo 2014 17 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Kwak 2002 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Miller 1992 19 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 |

| Miyamoto

2012 14 |

* | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Nayyar 2010 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Park 2009 15 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Sasaki 2011 22 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | - | * | 7 |

| Teoh 2017 21 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Tomioka 2014 20 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

Evaluation of PSA kinetics

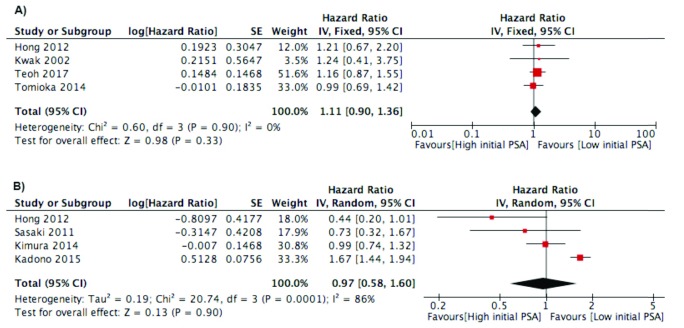

Initial PSA. Initial PSA before ADT treatment was evaluated in twelve studies 4, 9– 11, 16, 17, 19– 25. However, we only put four studies in PFS outcome and four studies in CSS/OS outcome because the studies analyzed initial PSA as a categorical parameter. No significant association between initial PSA and PFS was found, and the studies were homogenous (I 2=0%). In addition, there was no association between initial PSA and CSS/OS ( Figure 2). In qualitative analysis, four studies analyzed the association between initial PSA and PFS. All of the studies did not find significant results for PSA and PFS 16, 17, 19, 25. The result was the same when we analyzed the studies for OS/CSS outcome 9, 11, 16.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of association between initial PSA and: A) Progression Free Survival Outcome; B) Cancer Specific Survival/Overall Survival.

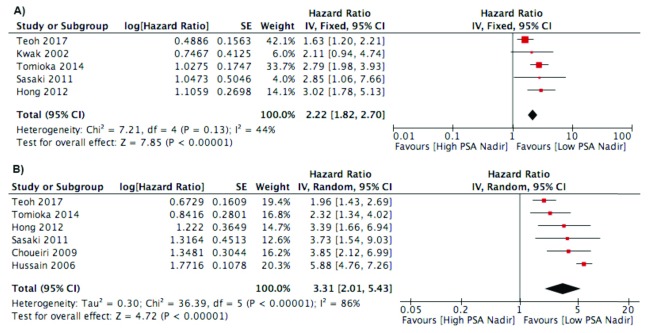

PSA Nadir. Six studies analyzed the effect of PSA nadir to influence survival using 0.2 ng/ml as a cut-off point 5, 10, 11, 20, 22, 23. Four studies analyzed the PSA nadir as a continuous variable 15, 17– 19. Teoh et al. used cut-off point 2 ng/ml as a PSA nadir that influence the survival 21. Bello et al. analysed nadir using 4 ng/ml as a threshold 25. Meta-analysis of the studies found an association of reduced PFS of patient with high PSA nadir (HR 2.22; 95% CI 1.82 to 2.70). The studies appear homogenous in the forest plot. In addition, high PSA nadir had a negative impact on the OS/CSS outcome with HR 3.31 (95% CI 2.01–5.43) ( Figure 3). In the studies using continuous measurement of PSA nadir, three studies found significant association of nadir PSA and survival 15, 18, 19. However, studies by Koo et al. found no significant result 17. Miyamoto et al. found the PSA nadir after first line hormonal therapy influenced survival 14.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of association between PSA nadir and: A) Progression Free Survival Outcome; B) Cancer Specific Survival/Overall Survival.

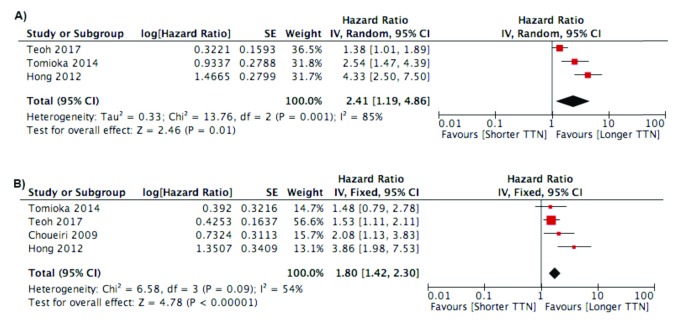

Time to Nadir (TTN). A total of seven studies analyzed the relationship between TTN and survival 5, 10, 16– 18, 20, 21. Of the seven studies, two studies used 8 months 5, 10, one study used 9 months 26, and one study used 12 months 20 as a cut-off. Three studies analyzed TTN as a continuous variable 16– 18. Meta-analysis was performed with showing a shorter TTN correlated with poor survival for both PFS (HR 2.41; 95% CI 1.19 – 4.86) or CSS/OS (HR 1.80; 95%CI 1.42 – 2.30) ( Figure 4). Studies using continuous variable of TTN showed a significant negative effect from shorter TTN on survival.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of association between TTN and: A) Progression Free Survival Outcome; B) Cancer Specific Survival/Overall Survival.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5256/f1000research.14026.d195553

For quality assessment a maximum 7 stars could be scored; 6 or 7 stars considered as high quality study, 4 – 5 stars corresponded with intermediate quality, and 0 – 3 stars showed low quality.

Copyright: © 2018 Afriansyah A et al.

Data associated with the article are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

http://dx.doi.org/10.5256/f1000research.14026.d195573

For quality assessment a maximum 7 stars could be scored; 6 or 7 stars considered as high quality study, 4 – 5 stars corresponded with intermediate quality, and 0 – 3 stars showed low quality.

Copyright: © 2018 Afriansyah A et al.

Data associated with the article are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

http://dx.doi.org/10.5256/f1000research.14026.d195577

For quality assessment a maximum 7 stars could be scored; 6 or 7 stars considered as high quality study, 4 – 5 stars corresponded with intermediate quality, and 0 – 3 stars showed low quality.

Copyright: © 2018 Afriansyah A et al.

Data associated with the article are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Discussion

Nowadays, clinicians have use PSA not only for screening for PCa, but also for follow up of patients after the treatment. The PSA indicates PCa condition following radical treatment in localized disease, and hormonal treatment in metastatic condition. PSA has a prognostic value, and now has been widen to several parameters such as PSA nadir, TTN, PSA doubling time, and PSA response after the treatment. There is controversy among previous study about the utilization of the PSA kinetic after hormonal treatment for predicting the progression to CRPC and survival.

The meta-analysis performed in this study did not find an association between survival and high initial PSA. Significant heterogeneity was observed due to scattered cut off points of high initial PSA amongst the studies included. Several studies found significant association of initial PSA and survival in univariate analysis, but lost significant after multivariate analysis. This condition showed us the aggressiveness of the cancer has not reflected by PSA alone, and other measures such as Gleason score, PSA nadir, and PSA decline may need to be considered 10, 15. This finding was different in localized diseases. High initial PSA reflects disease burden and was found to be correlated with the pathological stage, Gleason score, and the risk of metastasis. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline stratified the risk of localized disease based on PSA and that influences the treatment choice 27.

The significant findings of this study showed that lower PSA nadir was associated with good prognosis after ADT treatment. However, due to the variety of PSA nadir threshold, we could not conclude the best optimal threshold of PSA nadir. Most of the papers in this meta-analysis were using below 0.2 ng/ml PSA nadir. Morote et al. analyzed 185 patients with metastatic prostate cancer and they found nadir PSA above 0.2 ng/ml was associated with 20 times likelihood progression to CRPC 28. Moreover, Stewart et al. analyzed patient who received ADT due to biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy, and they suggested PSA nadir above 0.2 ng/ml was associated with significant progression and mortality 29. Keizman et al. used a different cut off for PSA nadir. They were using below 0.1 ng/ml because they found 4 times increased likelihood of biochemical or clinical progression in patients treated with intermittent ADT due to relapse after radical treatment 30.

Our findings found an association between longer time to get nadir PSA and survival. Longer time to nadir was associated with good prognosis. A study by Chung et al. found longer time to achieve nadir was a good prognosis for postoperative or post-radiation failure patients receiving ADT 31. Possible mechanisms of longer time to nadir associated with a good prognosis was associated with differentiation of PCa cells. Rapid reduction of hormone sensitive cancer cells may induce an environment for the development of hormone resistant PCa cells. In addition, PCa cells that have potential to differentiate into castration resistant cell show a rapid reduction of PSA due to ablation of the androgen receptor. Thus, rapid reduction of PSA is associated to development of CRPC and has a poor prognosis 32. This phenomenon is opposite to organ confined PCa receiving radical prostatectomy. In this setting, rapid decline of PSA result is associated with a better prognosis 33.

This study has some methodological limitations. We did not analyze the method of administration of ADT due to heterogeneity of ADT administration and that might be influenced survival. Some of the PSA kinetics evaluated in this meta-analysis had significant high heterogeneity. The strengths of this study include (i) a high quality of study based on NOS scale; (ii) meta-analysis just included study with multivariate analysis (iii) several parameters that were associated with the survival were found in this study and might be evaluated in the future research.

Conclusion

In this study, the intial PSA before administering ADT did not influence the PFS or OS/CSS. Higher PSA nadir during ADT treatment was associated with shortened progression time and survival. A longer time to nadir is a good prognosis of progression and survival of mPCA treated with ADT.

Data availability

The data referenced by this article are under copyright with the following copyright statement: Copyright: © 2018 Afriansyah A et al.

Data associated with the article are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication). http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Dataset 1. Quality assessment (based on NOS), hazard ratio, and standard error of studies included in initial PSA parameter. For quality assessment a maximum 7 stars could be scored; 6 or 7 stars considered as high quality study, 4 – 5 stars corresponded with intermediate quality, and 0 – 3 stars showed low quality. 10.5256/f1000research.14026.d195553 34

Dataset 2. Quality assessment (based on NOS), hazard ratio, and standard error of studies included in PSA nadir parameter. For quality assessment a maximum 7 stars could be scored; 6 or 7 stars considered as high quality study, 4 – 5 stars corresponded with intermediate quality, and 0 – 3 stars showed low quality. 10.5256/f1000research.14026.d195573 35

Dataset 3. Quality assessment (based on NOS), hazard ratio, and standard error of studies included in time to nadir parameter. For quality assessment a maximum 7 stars could be scored; 6 or 7 stars considered as high quality study, 4 – 5 stars corresponded with intermediate quality, and 0 – 3 stars showed low quality. 10.5256/f1000research.14026.d195577 36

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; referees: 1 approved

Supplementary material

Supplementary File 1: Completed PRISMA checklist.

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. : GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No.11 Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer,2013; [cited 2016 11 January]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buzzoni C, Auvinen A, Roobol MJ, et al. : Metastatic Prostate Cancer Incidence and Prostate-specific Antigen Testing: New Insights from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. 2015;68(5):885–90. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tangen CM, Faulkner JR, Crawford ED, et al. : Ten-year survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. 2003;2(1):41–5. 10.3816/CGC.2003.n.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kadono Y, Nohara T, Ueno S, et al. : Validation of TNM classification for metastatic prostatic cancer treated using primary androgen deprivation therapy. 2016;34(2):261–7. 10.1007/s00345-015-1607-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choueiri TK, Xie W, D'Amico AV, et al. : Time to prostate-specific antigen nadir independently predicts overall survival in patients who have metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer treated with androgen-deprivation therapy. 2009;115(5):981–7. 10.1002/cncr.24064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. : EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. 2014;65(2):467–79. 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mohler JL, Kantoff PW, Armstrong AJ, et al. : Prostate cancer, version 2.2014. 2014;12(5):686–718. 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huggins C, Hodges C: Studies on prostatic cancer II. The effects of castration on advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland. 1941;43(2):209–23. 10.1001/archsurg.1941.01210140043004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glass TR, Tangen CM, Crawford ED, et al. : Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate: identifying prognostic groups using recursive partitioning. 2003;169(1):164–9. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64059-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong SY, Cho DS, Kim SI, et al. : Prostate-specific antigen nadir and time to prostate-specific antigen nadir following maximal androgen blockade independently predict prognosis in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. 2012;53(9):607–13. 10.4111/kju.2012.53.9.607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hussain M, Tangen CM, Higano C, et al. : Absolute prostate-specific antigen value after androgen deprivation is a strong independent predictor of survival in new metastatic prostate cancer: data from Southwest Oncology Group Trial 9346 (INT-0162). 2006;24(24):3984–90. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. : The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses.[cited 2016 May 2]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miyamoto S, Ito K, Miyakubo M, et al. : Impact of pretreatment factors, biopsy Gleason grade volume indices and post-treatment nadir PSA on overall survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer treated with step-up hormonal therapy. 2012;15(1):75–86. 10.1038/pcan.2011.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park YH, Hwang IS, Jeong CW, et al. : Prostate specific antigen half-time and prostate specific antigen doubling time as predictors of response to androgen deprivation therapy for metastatic prostate cancer. 2009;181(6):2520–4; discussion 2525. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nayyar R, Sharma N, Gupta NP: Prognostic factors affecting progression and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. 2010;84(2):159–63. 10.1159/000277592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koo KC, Park SU, Kim KH, et al. : Predictors of survival in prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis and extremely high prostate-specific antigen levels. 2015;3(1):10–5. 10.1016/j.prnil.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim KH, Han KS, Kim KH, et al. : The prognostic effect of prostate-specific antigen half-life at the first follow-up visit in newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer. 2015;33(9):383.e17–22. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller JI, Ahmann FR, Drach GW, et al. : The clinical usefulness of serum prostate specific antigen after hormonal therapy of metastatic prostate cancer. 1992;147(3 Pt 2):956–61. 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)37432-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomioka A, Tanaka N, Yoshikawa M, et al. : Nadir PSA level and time to nadir PSA are prognostic factors in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. 2014;14:33. 10.1186/1471-2490-14-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teoh JY, Tsu JH, Yuen SK, et al. : Survival outcomes of Chinese metastatic prostate cancer patients following primary androgen deprivation therapy in relation to prostate-specific antigen nadir level. 2017;13(2):e65–e71. 10.1111/ajco.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sasaki T, Onishi T, Hoshina A: Nadir PSA level and time to PSA nadir following primary androgen deprivation therapy are the early survival predictors for prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis. 2011;14(3):248–52. 10.1038/pcan.2011.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kwak C, Jeong SJ, Park MS, et al. : Prognostic significance of the nadir prostate specific antigen level after hormone therapy for prostate cancer. 2002;168(3):995–1000. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64559-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kimura T, Onozawa M, Miyazaki J, et al. : Prognostic impact of young age on stage IV prostate cancer treated with primary androgen deprivation therapy. 2014;21(6):578–83. 10.1111/iju.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bello JO: Predictors of survival outcomes in native sub Saharan black men newly diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer. 2017;17(1):39. 10.1186/s12894-017-0228-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Teoh JY, Tsu JH, Yuen SK, et al. : Prognostic significance of time to prostate-specific antigen (PSA) nadir and its relationship to survival beyond time to PSA nadir for prostate cancer patients with bone metastases after primary androgen deprivation therapy. 2015;22(4):1385–91. 10.1245/s10434-014-4105-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mohler J, Antonorakis E, Armstrong A: NCCN Clinical Practice Guideline in Oncology. Version 2.2017. 2017.2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morote J, Esquena S, Abascal JM, et al. : Usefulness of prostate-specific antigen nadir as predictor of androgen-independent progression of metastatic prostate cancer. 2005;20(4):209–16. 10.1177/172460080502000403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stewart AJ, Scher HI, Chen MH, et al. : Prostate-specific antigen nadir and cancer-specific mortality following hormonal therapy for prostate-specific antigen failure. 2005;23(27):6556–60. 10.1200/JCO.2005.20.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keizman D, Huang P, Antonarakis ES, et al. : The change of PSA doubling time and its association with disease progression in patients with biochemically relapsed prostate cancer treated with intermittent androgen deprivation. 2011;71(15):1608–15. 10.1002/pros.21377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chung CS, Chen MH, Cullen J, et al. : Time to prostate-specific antigen nadir after androgen suppression therapy for postoperative or postradiation PSA failure and risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality. 2008;71(1):136–40. 10.1016/j.urology.2007.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crawford ED, Bennett CL, Andriole GL, et al. : The utility of prostate-specific antigen in the management of advanced prostate cancer. 2013;112(5):548–60. 10.1111/bju.12061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vesely S, Jarolim L, Duskova K, et al. : The use of early postoperative prostate-specific antigen to stratify risk in patients with positive surgical margins after radical prostatectomy. 2014;14:79. 10.1186/1471-2490-14-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Afriansyah A, Hamid ARAH, Mochtar CA, et al. : Dataset 1 in: Prostate specific antigen (PSA) kinetic as a prognostic factor in metastatic prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2018. Data Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Afriansyah A, Hamid ARAH, Mochtar CA, et al. : Dataset 2 in: Prostate specific antigen (PSA) kinetic as a prognostic factor in metastatic prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2018. Data Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Afriansyah A, Hamid ARAH, Mochtar CA, et al. : Dataset 3 in: Prostate specific antigen (PSA) kinetic as a prognostic factor in metastatic prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2018. Data Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]