Abstract

Background:

Delayed access to specialty care may increase inappropriate emergency department (ED) visits. However, the details of this relationship after referral to a specialist are unknown.

Methods:

The correlations in an academic medical center between time to new neurology patient appointments and nonurgent ED use are explored in this study. Access was measured as the number of days between the scheduling and outpatient appointment dates. A series of statistical analyses including correlation analysis, regressions, and hypothesis tests were conducted to investigate possible associations between delayed access to specialty care and ED visits, as well as the effect of ED visits on specialty care cancellation and no-show rates.

Results:

Of 19,505 new neurology patients, 310 visited an ED prior to their appointment, 95.2% (295) of whom had poor access (defined here as exceeding 21 days). Patients with access >21 days for new visits were 6.6 times more likely to visit the ED before their appointment date, 19% within the first week after scheduling. Patients who visited the ED between their booking and appointment dates were 2.3 times more likely to cancel or fail to attend their appointment.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that long access delays in specialty referrals can significantly increase ED costs and congestion. Further studies in other specialties to explore this relationship are warranted.

A June 2015 Institute of Medicine report focused on timely access as a fundamental expectation and key component of well-designed care systems,1,2 included among other recommendations: developing better understanding of care and cost consequences, adopting a larger systems view, and addressing interdependencies between different aspects of the care system of systems (e.g., primary, specialty, and urgent care). US emergency departments (EDs) experience more than 131 million visits annually,3 more than 40 visits per 100 persons. Patient severity studies estimate that between 33% and 50% of ED visits are inappropriate,4,5 composed primarily of 3 types: (1) nonurgent conditions, (2) urgent conditions but treatable in outpatient settings, and (3) needing urgent ED treatment that is preventable or avoidable.6

These potentially unnecessary visits are a significant contributor to ED overuse, overcrowding, inefficient ED resource utilization, long waits, delayed admissions, and higher costs.5,7–13 Although EDs provide excellent immediate care, nonurgent patients in emergency departments can be treated in less acute systems,4,14,15 with nonurgent ED visits costing roughly 3 times more than physician office visits.12,13,16,17 Additionally, improving appointment access to specialty care can significantly reduce inappropriate ED visits, care discontinuity, poor outcomes, and hospitalization risk.18

The analyses described in this article are motivated by observations at a large teaching hospital regarding the considerable volume of nonurgent ED visits by patients seeking care for neurologic complaints and the possible correlation with poor neurology appointment access.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The reported analyses in this article used de-identified data without patient information, for which written informed consent was not required. This study was conducted as part of a quality improvement project and therefore did not undergo institutional review board review.

Design overview

Unlike the questionnaire-based survey methods often preferred in the literature, this study seeks possible patterns and correlations between ED visits and delayed access to specialty care based on arrival and scheduling data. Information about 28,489 patient visits to the emergency and neurology departments at a large academic hospital over 18 months were collected from the hospital's PATCOM (Keane, Inc., Boston, MA) and EDIS (Medhost, Franklin, TN) software and GE Healthcare–IDX (Cleveland, OH) scheduling software. A series of statistical analyses were conducted on these data to explore the below hypotheses about possible relationships between delayed access in specialty care and ED visits, as well as the effect of ED visits on specialty care cancellation and no-show rates. All analyses were performed on the de-identified data using MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA), Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA), and R (R Core Team 2012, Vienna, Austria).

Setting

The neurology department in this study comprises 11 units and over 220 physicians who see roughly 67,000 new and established patients per year, with an average of roughly 1,580 new adult and child neurology appointments per month. A total of 19,505 new patient referrals were examined over 18 months. Access delays were measured as the number of days between the scheduling and appointment dates. Although in some cases patients chose to wait for a specific provider, the proportion is thought to be fairly small.

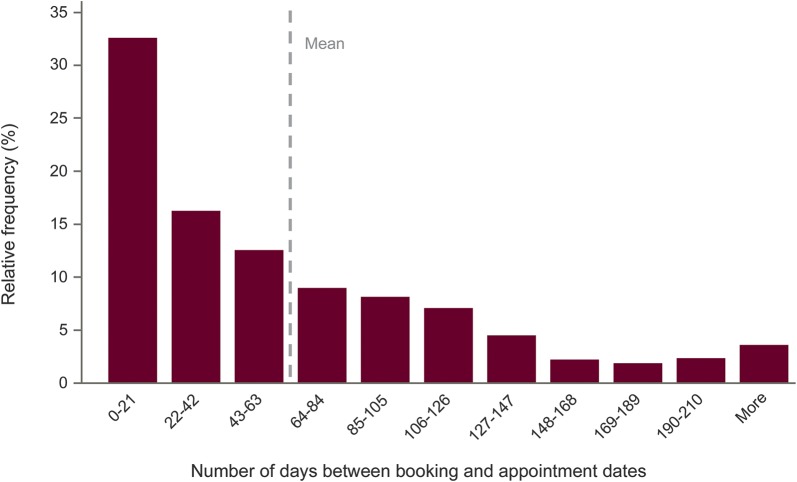

Poor access was defined as new appointment delays greater than 21 days, which is approximately the national average for access to outpatient neurology appointments. At the time of our study, the average wait for a neurologist appointment was 63.5 days, with 67.2% exceeding 21 days, and 39.5% cancelled or unattended (figure 1). Established patients usually schedule appointments at the time of their previous visit and thus experience access delays much less frequently.

Figure 1. Appointment access delays for new neurology patients.

Appointment access delays for new neurology patients (mean 63.5 days, SD 64.1 days, 67.2% exceeding 21 days).

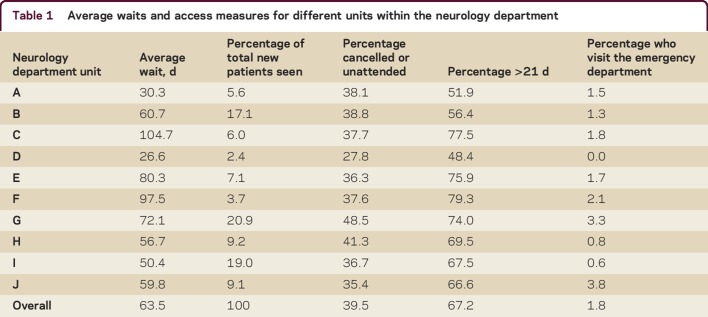

Table 1 summarizes new patient volumes, wait times, and other access performance measures for each unit within the neurology department. Our ED visit inclusion criteria were (1) the patient scheduled a new patient appointment in the neurology department, (2) the ED visit occurred between scheduling and occurrence of the neurology appointment, and (3) the chief complaint for the ED visit was neurologic (45% of 476 recorded chief complaints of ED visits meeting criteria 1 were for neurologic issues). ED visits that did not satisfy these 3 criteria were excluded from the analyses.

Table 1.

Average waits and access measures for different units within the neurology department

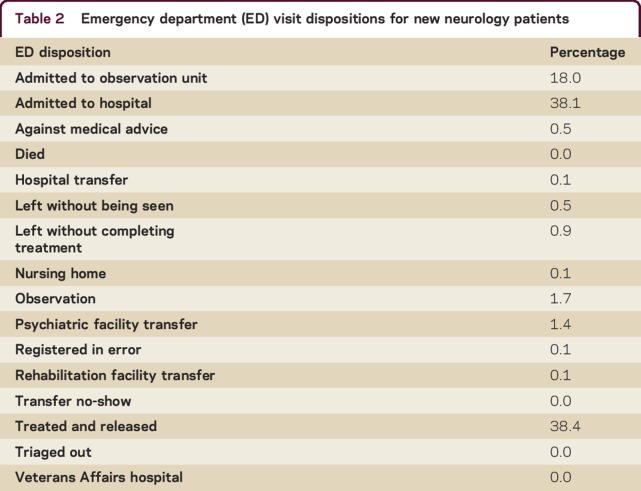

ED dispositions recorded as “treated and released” were used as a proxy (table 2) to determine if an ED visit was for nonurgent care. Since this was a prospective study, some scheduled appointments had not occurred yet (16.8%), so we conservatively assumed these would be successfully completed as neurology appointments.

Table 2.

Emergency department (ED) visit dispositions for new neurology patients

Data analysis

We conducted a series of correlation analysis, regressions, and hypothesis tests to investigate possible associations between ED visits and poor neurology access. We developed a null and 3 alternative hypotheses (H0, H1, H2, H3, respectively):

H0: Poor access has no relation to the amount of inappropriate ED visits and patients who visit the ED before their neurology appointment are no more likely to cancel or miss that appointment.

H1: Patients with poor access are more likely to visit the ED than those with good access.

H2: Patients with poor access are more likely to have a nonurgent ED visit within the first week after they schedule their appointment than those with good access.

H3: Patients who go to the ED after booking an appointment are more likely to cancel or miss their clinic appointment than those who do not visit the ED.

Significance levels of 0.05 were used for each hypothesis test, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

RESULTS

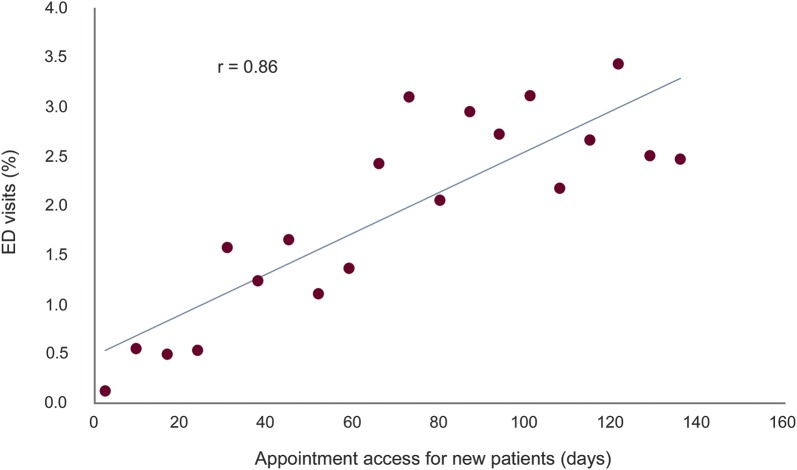

To test the first hypothesis, we conducted a Pearson correlation test and regression analysis between the percentage of new patients who visited the ED and new patient access to the neurology department. Patient waits were grouped into 20 1-week duration increments from 1 week to 20 weeks. The average wait in each range was regressed against the percentage of patients in that range who visited the ED (figure 2). We excluded ED visits that occurred on the same day that an appointment was scheduled due to uncertainty of whether the ED visit precipitated scheduling the appointment. Waits exceeding 20 weeks also were excluded (fewer than 5% of referrals), since these outliers were thought mostly to represent appointment dates scheduled for patient convenience rather than caused by poor access.

Figure 2. Correlation between access delays and probability of an emergency department (ED) visit.

Correlation between access delays and probability of an ED visit between the booking and appointment dates (access was grouped into 20 1-week duration ranges; the average wait time in each range was regressed against the percentage of patients in that range who visited the ED).

The resulting correlation coefficient was r = 0.86 (p < 0.001) with a slope coefficient of 0.02% (p = 0.000), suggesting that on average every additional 10 days of delayed access increases ED visits by new patients by 0.2%. Thus, the longer the access delay for a neurology appointment, the more likely patients are to visit the ED after booking their appointment. A proportion test was also conducted to test for differences between poor vs good access rates for patients with ED visits occurring between their scheduling and appointment dates. A total of 14,617 new patients had poor access (delay >21 days), 295 (2.02%) of whom visited the ED, vs 15 of 4,888 new patients with good access (0.31%). Thus patients with appointment access greater than or equal to 21 days were 6.6 times more likely to visit the ED as patients with appointment delays less than 21 days (95% CI 3.92–11.04).

To test the second hypothesis, we explored whether patients with appointment delays exceeding 21 days visited the ED due to nonurgent concerns within the first week after scheduling their appointment at a greater rate than patients with good access (≤21 days). Of the 20 identified patients who visited the ED within the first week after scheduling their appointment and who were treated and released, none of them had good access (≤21 days). Furthermore, none of the 20 patients who visited the ED within the first week after scheduling their appointment (and were subsequently treated and released) had good access (≤21 days).

To test the third hypothesis, we investigated whether the percentage of patients who kept their neurology appointment differs depending on whether they visited the ED in the interim. We conducted a large sample test of proportions to compare neurology cancellation or missed appointment rates for patients who visited the ED vs nonvisitors. A larger rate of patients who visited the ED subsequently canceled or missed their appointments (55%) than those who did not visit the ED (24%) (p < 0.001), being 2.3 times more likely to cancel or miss their appointment (95% CI 2.07–2.57).

DISCUSSION

Inappropriate ED visits remain a major contributor to ED crowding.5 Our findings suggest that patients who have been newly referred to a neurologist but cannot receive timely appointments are more likely to visit the ED to obtain more immediate care. This is disruptive to ED performance and costly. In our study, a new neurology patient department visit had an average claims cost of $194 (based on a work Relative Value Unit [RVU], facility RVU, and conversion factors of 3.17, 2.37, and $35, respectively19). In contrast, an ED visit at the same hospital for a neurologic complaint costs roughly $655, which is 3.37 times greater than for an office visit, translating with this department's volumes to approximately ($644 − $194) × (295 × 0.67) = $91,278 increased costs annually. In the present study, we assume that the tests (e.g., MRI) ordered routinely at the outpatient department cost the same as the tests ordered emergently at the ED.

Patient dissatisfaction with appointment delays and deterioration in their condition (either patient-perceived severity or physician assessment) are thought to be 2 main reasons for these ED visits. Patient perceptions may be stronger triggers for inappropriate ED visits than their actual severity,20 underscoring the effect of poor access and delayed diagnoses on patient anxiety. Until better access systems can be designed, one approach for neurology patients with long access delays may be to more immediately provide them with some understanding of their health condition, such as via an e-consult or other type of virtual visit. Walk-in neurology clinics or primary care consults with a nurse practitioner also may help fast-track patients in greater need of urgent neurologic care. Some of these alternative approaches including offering an e-consult to the primary care physician (PCP) and virtual visits with patients are now being piloted in the neurology department. It is hoped that the pilot projects will help clarify the root cause of the referrals to neurologists and also encourage improved team-based care between the PCPs and neurologists.

This study has a few limitations. First, it considered only one specialty care unit and ED at the same hospital, so similar studies in other settings might be conducted before forming broad conclusions. Second, we conservatively assumed all in-process appointments eventually are attended, whereas some cancellations by these patients also are likely. Third, in addition to ED disposition, a more complete understanding of true urgency could be based on a patient's chief complaints during ED visits, emergency severity index, and physician-assigned diagnosis.

Timely access to care, ED congestion, and overuse of scarce and expensive resources are ubiquitous and persistent problems across health care. As with any complex system of systems, multistrategy approaches are likely needed to design improved delivery systems with reliable capability to provide better care at lower costs. Among these, reducing time until first visit or diagnosis can help reduce patient anxiety and ED overuse.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Editorial, page 472

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S. Nourazari: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, statistical analysis. D.B. Hoch: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data. S. Capawanna: study concept or design, study supervision. R. Sipahi: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data. J.C. Benneyan: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, statistical analysis, study supervision, obtaining funding.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) (IIP-1034990) and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) (1C1CMS331050). Any views or opinions presented herein are solely those of the authors and not the NSF or CMMI.

DISCLOSURE

S. Nourazari reports no disclosures. D.B. Hoch holds stock/stock options from Merck, Regeneron, Biogen Idec, and Medtronic. S. Capawanna reports no disclosures. R. Sipahi receives research support from National Science Foundation and from a Northeastern University, College of Engineering, Faculty Fellow Award. J.C. Benneyan serves on the editorial boards of IIE Transactions on Healthcare, Healthcare Management Science, Patient Safety and Quality Healthcare Operations, Research in Health Care, and Computers and Industrial Engineering; and receives research support from National Science Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Transforming Health Care Scheduling and Access: Getting to Now. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan GS. Health care scheduling and access: a report from the IOM. JAMA 2015;314:1449–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss AJ, Wier LM, Stocks C, Blanchard J. Overview of emergency department visits in the United States, 2011. In: Hcup Statistical Brief #174. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD; 2014. Available at: hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb174-Emergency-Department-Visits-Overview.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen LA, Burstin HR, O'Neil AC, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. Nonurgent emergency department visits: the effect of having a regular doctor. Med Care 1998;36:1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Northington WE, Brice JH, Zou B. Use of an emergency department by nonurgent patients. Am J Emerg Med 2005;23:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrick DL, Murray TP, Bigby J, Boros A. Efficiency of emergency department utilization in Massachusetts: appendix A. In: Data and Methodology: Massachusetts Health Care Cost Trends. Boston: Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance & Policy; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher JE, Lynn SG. The etiology of medical gridlock: causes of emergency department overcrowding in New York City. J Emerg Med 1990;8:785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, Solberg LI, Lurie N, Camargo CA Jr. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med 2003;42:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, Schears RM, Bookman KJ. Emergency department crowding, part 1: concept, causes, and moral consequences. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. The future of emergency care in the United States health system. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:1081–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derlet RW, Richards JR. Overcrowding in the nation's emergency departments: complex causes and disturbing effects. Ann Emerg Med 2000;35:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RM. The costs of visits to emergency departments. N Engl J Med 1996;334:642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger EA. $9,000 bill to diagnose shingles? Ann Emerg Med 2010;55:A15–A17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMCS) and US Department of Health & Human Services. Reducing Nonurgent Use of Emergency Departments: Improving Appropriate Care: Appropriate Settings: CMCS Informational Bulletin. 2014. Available at: medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/CIB-01-16-14.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honigman LS, Wiler JL, Rooks S, Ginde AA. National study of non-urgent emergency department visits and associated resource utilization. West J Emerg Med 2013;14:609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamezai A, Melnick G. Marginal cost of emergency department outpatient visits: an update using California data. Med Care 2006;44:835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McConnell KJ, Gray D, Lindrooth RC. The financing of hospital-based emergency departments. J Health Care Finance 2007;33:31–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentice JC, Pizer SD. Waiting times and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2008;8:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare. Available at: cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare.html. Accessed June 28, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham PJ, Clancy CM, Cohen JW, Wilets M. The use of hospital emergency departments for nonurgent health problems: a national perspective. Med Care Res Rev 1995;52:453–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.