You know that feeling when you meet someone and your heart skips a beat?

Yeah, that’s arrhythmia. You can die from that.

Anonymous

The majority of patients with a cardiac arrhythmia are asymptomatic; this has been so from earliest times. The patient with a cardiac arrhythmia may or may not feel anything. Some patients may complain of “racing heart” or “skipped beats” or may feel dizzy or faint.

Palpation of the pulse was the sole “window” into the heart for 1000 of years until the mid-20th century. Throughout the history of medicine, the pulse was an important parameter in assessing cardiac dysfunction.

Pulse taking is an ancient technique in medicine. There are many historical illustrations of physicians taking the pulse of a patient. Ancient Egyptian, Chinese, Indian, Greek, Medieval, Arab-Islamic, and modern physicians know the value of examining the pulse. It is part of what we call our “vital signs.”

Pulse taking is still an integral part of medical practice today for the pulse is an important diagnostic sign and can be used to prognosticate the course of illness. A physician well versed in “reading” or interpreting the different characteristics of the pulse in disease is considered a “good doctor” in the past; now, only the nurse takes the pulse.

Nowadays, pulse-taking has evolved into a highly technical field. We now know so much more about the generation of electrical activity in the heart – its normal and abnormal physiology – that new therapies for cardiac arrhythmia have been fashioned. In this day and age, highly technical and sophisticated diagnostic devices help the physician arrive at a diagnosis and make a plan for treatment.

Examination of the pulse can still give us important diagnostic and therapeutic clues. It is, therefore, fitting to review the history of the assessment of the pulse in medicine. It is very interesting to look at the different methodologies for evaluation of the pulse in ancient, Arab-Islamic, medieval, and modern medicine.

THE ROOTS OF MEDICINE

It is not known where medicine started. Some historians say from ancient Egypt, whereas others claim from Mesopotamia. There is a debate about it, but in primitive cultures, the health of a person is closely linked to religion and magic. Primitive peoples believe that the visible world is pervaded by invisible forces or spirits that affect the lives of the living. They believe that the Gods had power over mortals and controlled man's destiny. When angered, the Gods punished man in various ways: disease, plague, death, natural catastrophes, misfortunes, etc. Appeasement of the Gods through prayers, offerings, and sacrifice was, therefore, a central aspect of daily life and served as prophylaxis against disease and misfortunes.

Shaman or witch doctor or medicine man in ancient cultures

When someone falls ill, a person regarded as being able to “speak to spirits” – good and evil – will bring the person back to health and this is usually the shaman or witch doctor or medicine man. Ancient cultures have always believed in the shaman, a human link to the spirit world. The shaman enters a trance state during a ritual through dance, drumming, and ingestion of powerful psychedelic plants to speak to the gods, demons, or spirits of the supernatural world to determine the nature of the problem. It is the job of the shaman to find out why and what should be done. Physical examination was nonexistent. The shaman has knowledge of certain plants and mineral substances with properties to alleviate specific complaints. Many of the primitive healer's techniques had no rational or pharmacological basis.

Nowadays, our society has a tendency to emulate the techniques used by the shamans of old. Modern medicine has yet to endorse their value. The shaman does not perform physical examination, let alone perform an analysis of vital signs, which are important components of patient care as they determine which treatment protocols to follow, provide critical information needed to make lifesaving decisions, and confirm feedback on treatments performed.

On the internet, however, there are many sites claiming that drumming has therapeutic benefits. Current research (it is claimed) is now verifying the therapeutic effects of ancient rhythm techniques from accelerating physical healing to boosting the immune system and producing feelings of well-being. However, not one of these sites references a medical paper to lend credence to their claims. It seems a lot of these claims are anecdotal. On Medscape, there was an interview with a researcher in UCLA who has done research on rhythm and thinks that drumming has therapeutic potential, but that research has yet to validate its value.[1]

Before the evolution of our knowledge of the human body, discoveries of new drugs, and interventions to treat diseases, there was the shaman – the first healer. ”There were shamans before there were gods.”[2]

The pulse of course is one of the most important diagnostic and prognostic signs in medicine. From ancient to modern times, pulse monitoring in health and disease states was and is a vital component in fitness assessment. Ancient physicians did not have sophisticated equipment to assess the pulse as we have in modern times, but they developed highly refined ways of interpreting and analyzing the pulse through palpation. The pulse rate, its strength, and its rhythms tell us a lot about the patient's or person's state of heath. The ancient physicians realized this so that pulse taking developed into an art form.

MESOPOTAMIA: EARLIEST RECORD OF “PULSE-TAKING”

Gilgamesh, the hero-king in the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh uttered the following lament on the death of his best friend in 2600 BC:

I touch his heart but it does not beat at all.[3]

Gilgamesh, c. 2600 BC

The passage is thought to be the earliest reference to pulse-taking indicating that, as early as 2600 years BC. Man understood that the heart beats and can be palpated.

Gilgamesh on the death of his friend Enkidu

The epic of Gilgamesh was written in ancient Iraq, when man lived in city-states. This is the oldest written story known to exist. The oldest existing versions of this epic date to c 2000 BC, in Sumerian cuneiform.[4] The setting is a time when people believed gods ruled the world and often got involved in the lives of mortals. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, a city-state in ancient Iraq, went in search of the plant for eternal life after the death of his best friend Enkidu who was brought up in the wild and knew nothing of civilization. Initially, they were enemies but each grew to respect the other and they became friends. The friendship of Gilgamesh and Enkidu blossomed and each taught the other about life. After meeting Enkidu and becoming his friend Gilgamesh became a better king to his people because he understood them better and he was able to identify with them. As for Enkidu, he was able to move beyond his fears. The death of Enkidu was the driving force for Gilgamesh to confront his mortality and search for the plant of eternal life.[4]

The particular lament of Gilgamesh written more than 4600 years ago when his friend died, “I touch his heart and it does not beat at all,” should not fool us into thinking that Mesopotamian medicine was sophisticated. We know from history books, especially on daily life and culture of ancient Mesopotamia that the Mesopotamians knew little about anatomy and physiology because they were restricted by the religious taboo against dissecting a corpse. For divinatory purposes, the Mesopotamians dissected only the liver and lungs of perfectly healthy animals. The doctors understood the importance of taking a patient's pulse, and they could offer rational explanations for many symptoms and diseases. They had physicians and healers who dealt with spirits. When Mesopotamian civilization was declining, magic and superstition became dominant.[5]

The text also does not tell us whether Gilgamesh placed his hand on the chest, on the head, or on the extremities. The passage merely means that Gilgamesh understood that the heart is the life-sustaining organ and that its motion can be palpated. It seems he had knowledge of where the heart should be.

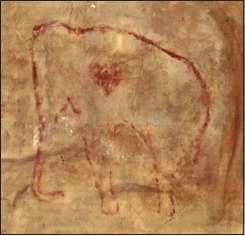

15000-year-old drawing of a mammoth in a prehistoric cave in Spain

There is a drawing depicting a mammoth with a leaf-shaped dark area where the heart should be in a prehistoric cave (El Pindal cave in Spain) and dated 15,000 years ago.[6,7] Prehistoric societies were mainly hunting societies and the heart must have been the organ that attracted the attention of man from the earliest times because he found it beating as long as there was life and soon must have discovered that the best way to kill an animal is to hit it through the heart. Therefore, it should not be surprising then that by 5000 years ago, when man settled into city-states, he already realized that the heart is an organ vital to life.

ANCIENT EGYPT

The art of medicine in ancient Egypt was renowned throughout the ancient world. It has been said that if one had to be ill in ancient times, the best place to be would probably have been Egypt.

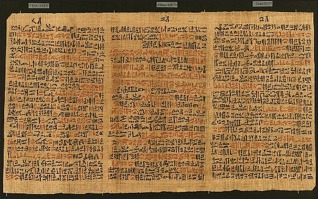

We know the state of the ancient Egyptian's practice of medicine from their writings, from nine medical papyri, with the most ancient dating back to 1950 BC. While it is undisputable that the medicine of the ancient Egyptians is some of the oldest documented and highly advanced for its time, Egyptian medical thought was unchanged for millennia.

Their medicine included simple, noninvasive surgery, setting of bones, and an extensive set of pharmacopoeia. However, their medicine was often mixed with magical incantations and their pharmacopeia contained unconvincing ingredients for certain diseases. Medical texts specified specific steps of examination, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatments that were often rational and appropriate.[8]

Other information that we have of the state of their medicine comes from the images that often adorn the walls of Egyptian tombs and the translation of the accompanying inscriptions. Egyptian medical thought influenced later traditions including the Greeks.[8]

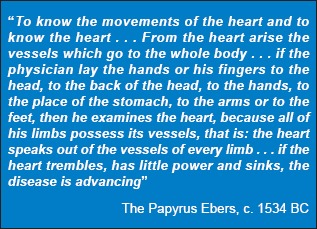

Ancient Egyptian doctors knew that the body had a pulse, and that it was associated with the function of the heart. They believed that the heart gives rise to vessels that can be palpated. They believed “the heart speaks out of every limb” [this is so true]. The quotation is contained in the Papyrus Ebers, written about 3500 years ago. It is 108 pages and consists of extracts drawn from different sources and compiled by the scribes.

A Section of the Papyrus Ebers

The Papyrus Ebers shows that, at that early period, the Egyptians had a degree of knowledge about how the human body works. Anatomy and physiology are recorded on the papyrus. That they had knowledge of anatomy should not be surprising since they practiced mummification. There are many prescriptions showing the treatment of many disorders.[8] It defines the heart as the center of the blood supply, with vessels attached for every member of the body.

The papyrus is not purely scientific however. Historians say it begins with a magic introduction and parts contain theological tendencies and crediting the gods with the origin of the prescriptions. The compilation is said to contain 877 paragraphs detailing therapeutic recipes, diagnostic notes, and theoretical considerations of life, health, and disease devoid of magical or religious considerations. The papyrus also contains detailed clinical description of various illnesses.[9,10]

The body of knowledge in cardiovascular anatomy and physiology of the ancient Egyptians is contained in three medical papyri: the Edwin Smith papyrus (c. 1550), The Ebers papyrus (c. 1534 BC), and the Brugsch Papyrus (c. 1300 BC). They are the most ancient Egyptian medical writings, but they are dated from a later period than the Mesopotamian (Babylonian) medical tablet. However, the Egyptian Papyri are believed to be copies of a much older and lost literature, from a period well over 3000 BC.[11,12]

Palpation of the pulse was very important. It defines the heart as the center of the blood supply, with vessels attached for every member of the body. It is undisputed that the ancient Egyptians were the first to describe the relationship between heartbeat and peripheral pulse. They counted the pulse during palpation. It was counted with the aid of an earthenware vessel that acted as a clock. This vessel had a tiny hole at the bottom, allowing the water to drip, drop by drop. The pulse rate was determined by correlating it with the drops of water escaping from the vessel. The markings on the side of the bowl divide the day into 24 increments, each increment representing 1 h.[12]

The ancient Egyptians observed and recorded important cardiovascular phenomena for which they had no explanation. For example, they noted that, when the patient fainted, the pulse could be expected to disappear; they also described the weak, thready pulse; and the displacement of the heart impulse on the left side of its usual position, now recognizable in retrospect as left ventricular enlargement.[13] They seem to have been able to detect abnormalities of the heartbeat. Extrasystoles were called “forgotten beats”;[13] excessive salivation was called “flooding of the heart”[13] and which might have represented some kinds of cardiac disease that today would be interpreted as heart failure. No doubt, those ancient Egyptian doctors were very poetic.

They had a very basic knowledge of a cardiac system but did not realize that blood circulated around the body. They were unable to distinguish blood vessels, nerves, or tendons.[14] But of course, it would be too much to expect the ancient Egyptians that knowledge. Sigerist, the well-known historian said of them: “Although the disease hypotheses and empiric observations of the ancient Egyptians were unproven by experimentation, their efforts to correlate the action of food, air, and blood to explain disease have been viewed as the beginning of physiology.”[15]

CHINESE MEDICINE

Traditional Chinese medicine practitioner performing pulse diagnosis

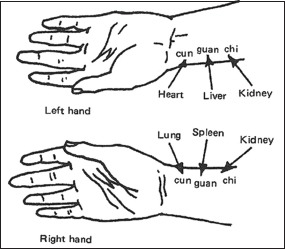

In China, diagnosis was mainly carried out by pulse taking. It was called pulse diagnosis and this developed to an art form. This information comes from the Huangdi Neijing or The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine, an ancient treatise on health and disease and supposedly written by the famous Chinese emperor Huangdi in 2600 BC.

Historians claim Huangdi is a semi-mythical figure and the book probably dates from a later period, like around 300 BC and that maybe the book is a compilation of the writings of several authors. The book takes the form of a discussion between Huangdi and his physician in which Huangdi inquires about the nature of health, disease, and treatment.

Whatever the book's origin, it has been influential as a reference work for practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine and has been found to be useful even in the modern era. In the book, health and illness are caused by the imbalance of two basic forces, yin and yang, and by the influence of the five elements (water, fire, metal, wood, and earth) on the organs of the body.[16]

The ancient physicians in China considered examination of the pulse as an essential part of Chinese medical practice. Practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine use pulse diagnosis as a tool to assess the health of all the major organ systems of the body. Technique in taking the pulse and its interpretation is vital in making a diagnosis, fashioning treatment, and prognostication.

In traditional Chinese medicine, there are 26 categories of pulses[17] which can be quite confusing; each pulse type indicates a particular disease or syndrome or a disease in other organs. When taking the pulse, various factors are taken into accounts such as the time of day, season, and sex of the patient. Treatment included drugs, diet, acupuncture, and guiding the patient toward a healthier lifestyle.

The question has been raised whether traditional pulse diagnosis the Chinese way is relevant in our modern medical practice with the wealth of information we derive from modern tests? Even though reliance on pulse diagnosis is very subjective, pulse taking is still a central and key part of modern medical practice. No doubt this ancient art form as developed in China can be very useful when combined with more objective modern devices. It can teach physicians the proper method of taking the pulse, the factors that influence the pulse, and its interpretation. It is one method of determining the internal conditions of patients with the aim of deciding on a therapeutic regimen.

INDIAN MEDICINE

The medicine that developed in India more than 3000 years ago is known as Ayurveda or knowledge of life. It is taken from two Sanskrit words Ayur = life and veda = knowledge. It is one of the world's oldest medical systems. In Indian mythology, medical knowledge was transmitted from the gods to sages and then to human physicians.[18] The basic doctrine is a belief that health and wellness depend on a delicate balance between the mind, body, and spirit. It deals with matters relating to health, day-to-day life, and longevity. It has many things in common with traditional Chinese medicine. Both are considered types of complementary or alternative medicine in modern times. Both focus on the patient rather than the disease, aiming to promote health and enhance the quality of life, and treating the person as a whole (holistic). Life is composed of opposing forces that affect our health, and when these forces or energy fall out of harmony, disease develops. This is reminiscent of prehistoric medicine where when the spirits or gods are offended, disease develops. The spirits or gods have been replaced with “forces” or “energy.”

In ayurvedic medicine, the pulse is an integral part of diagnosis as in traditional Chinese medicine, but pulse taking in Ayurveda is not as detailed as traditional Chinese medicine. Both systems fundamentally aim to heal the whole person not just the disease by promoting health and enhancing the quality of life, with therapeutic strategies for treatment of specific diseases or symptoms in a holistic fashion.

ANCIENT GREEK MEDICINE

Plato, Socrates, Aristotle, Hippocrates… these are all famous Greek names throughout history. Greece has produced many philosophers and physicians that we admire and who have made important discoveries, but we do not all remember their names. We look to Greece as the place of origin of modern scientific medicine. No doubt there are many modern medical practices that can be traced to ancient Greece. Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC), who is considered the father of medicine was from Cos or Kos, Greece. The Hippocratic writings attributed to him have been analyzed by medical historians, with the consensus that those medical documents were written by several individuals.

Ancient Greek medicine developed around 700 BC with the waning of Egyptian civilization and prevailed until the end of antiquity which according to historians occurred around 600 AD.[19] Compared to the Egyptians, the ancient Greek physician was more rational in their attitude toward disease. Initially, the ancient Greeks, just like the Babylonians and Egyptians before them, regarded illness as a divine punishment and healing a “gift from the gods.” Later, they attempted to identify the material causes for illness with a move away from superstition toward scientific enquiry. The Greek physician began to take a greater interest in the body itself and explore the connection between cause and effect, the relation of symptoms to the illness and the success or failure of various treatments.[20]

The ancient Greeks believed in “pneuma” (air or breath). In a religious context, pneuma also stood for “spirit” or “soul.”[21] They believed pneuma filled the arteries which was necessary for life and that it was the form of circulating air necessary for the systemic functioning of vital organs. Their philosophy and medical theories flooded such belief.

Although Hippocrates is reported to describe the characteristics of the arterial pulse in several disease conditions such as fever and lethargy, he did not realize the value of it as a sign of disease. It was Praxagoras of Cos who realized the value of using the pulse as an indicator of disease. He is credited for the first use of the pulse as a tool for diagnosis. Based on his observations, he formulated several theories about the arterial pulse.[22]

The ancient library of Alexandria

The center of Greek learning in the 4th century, however, was in the city of Alexandria in Egypt. The city was founded by Alexander the great in 331 BC and was ruled by the family of Ptolemy, the general of Alexander. The city became renowned and fabled in antiquity for its treasures of wisdom.

From around the 3rd century BC to the 7th century AD, Alexandria was a place of inspiration. It had a library and a museum, both of which were the envy of the civilized world. The library contained antiquity's most extensive collection of recorded thought. Alexandria held an impressive position in the evolution of medical theory and practice. It was a beacon to learning and discovery. Therein Alexandria, physicians performed human dissection and carried out experimentation to test their hypotheses. Two of its eminent physicians historically celebrated in medicine were Herophilus (c. 330 – 260 BC) and Erasistratus (c. 330 – 260 BC).[23]

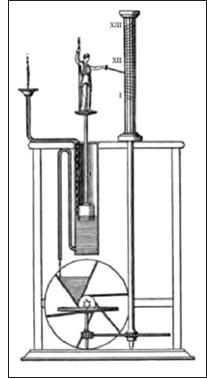

Herophilus’ klepsydra for counting the pulse

Herophilus who is considered the father of anatomy and physiology endeavored to practice a new “scientific” medicine by embarking on a new study of the human body based on human dissection.[23] His most important contribution to clinical medicine was the diagnostic value of the pulse. The teacher of Herophilus was Praxagoras who first used the pulse as a tool for diagnosis and who formulated several theories about the arterial pulse,[22] one of which was that pulsation only occurs in the arteries, not in the veins.[22]

Herophilus held that the pulse has rhythm as in music and he developed a system for counting the pulse rate. He constructed a portable water clock or clepsydra which contained a specified amount of water. He used this device to count the pulse rate of his patients.[22] Although Herophilus recognized the importance of determining the pulse rate, his followers did not continue this particular aspect of his studies and there is rarely mention of pulse rate until the 15th century.

The other celebrated physician of antiquity was Erasistratus (c. 330 – 260 BC) who was a contemporary of Herophilus (c. 330 – 260 BC) in Alexandria. It is reported that Galen (a second-century Greek physician and philosopher and considered the most important physician after Hippocrates in the ancient world) mentioned that Erasistratus came very close to understanding the circulation.[22]

Erasistratus stated that the heart and arteries do not move at the same instant; the arteries dilate while the heart contracts and vice versa. He recognized that the motion of arteries follows the contraction of the myocardium. He correctly observed and explained that dilation of the arteries is a passive expansion of the vessel but incorrectly assumed that this was due to movement of pneuma along the course of the arteries. The Greeks believed at that time that arteries contained pneuma whereas veins contained blood. It is not, however, explained how the pneuma reaches the heart and arteries.[22]

Erasistratus contemporary Herophilus also believed that dilation of the arteries draws in pneuma from the heart and contraction of the arteries moves it forward, and this interplay generates the arterial pulse. This concept on the pulse was believed by the Greeks to be true until the time of Galen when arteries were discovered to contain blood and air. Galen wrote a treatise on the pulse in the Middle Ages called De Pulsuum Differentiis[22] and his theories dominated western medical thinking for centuries after his death.

CONCLUSION

Using the pulse to interpret health is a very old art form. The different medical traditions have developed ways to “read” the pulse in their own unique way but no doubt each tradition borrowed and was influenced from an older civilization. It took humans 1000 of years of experimentation and rationalization to arrive at where we are today. The take-home message from an examination of the medical history of pulse taking is that the physician who is well versed in interpreting the nuances of the pulse is perceived as an excellent doctor. Even in this modern age of technology, where the pulse can be assessed accurately and more objectively, taking the pulse of a patient is still valuable and should not be overlooked or forgotten. Pulse diagnosis is a cherished art.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.thoughtco.com/drum-therapy-1729574 .

- 2.La Barre W. The Ghost Dance: The Origins of Religion. London: George Allen & Unwin; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalley S, translator. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.ancient-literature.com/other_gilgamesh.html .

- 5. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.healthguidance.org/entry/6308/1/Ancient-Civilizations-Mesopotamia.html .

- 6. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.donsmaps.com/cuevadelpindal.html .

- 7.Hajar R. The pulse in antiquity. Heart Views. 1999;1:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.m.dailyhunt.in/news/india/english/bayside+journal-epaper-baysidej/ancient+egyptian+medicine-newsid-75604933 .

- 9. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.wrf.org/ancient-medicine/oldest-medical-books.php .

- 10.Ghalioungui P. Magic and Medical Science in Ancient Egypt. London: Hodder and Stoughton; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons AS, Petrucelli RJ. Medicine an Illustrated History. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.; 1087. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acierno LJ. The History of Cardiology. London: Parthenon Publishing Group; 1994. Physical examination; pp. 447–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunn JF. Ancient Egyptian Medicine. London: British Museum Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/info/medicine/ancient-egyptian-medicine.php .

- 15.Sigerist HE. A History of Medicine. Primitive and Archaic Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 16. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 22]. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/336/7647/777.2.full .

- 17.Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Turnbull F, Neal B, Ninomiya T, Algert C, Arima H, et al. Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2008;336:1121–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39548.738368.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 28]. Available from: http://www.itmonline.org/arts/pulse.htm .

- 19. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/info/medicine/ancient-greek-medicine.php .

- 20. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.ancient.eu/Greek_Medicine/

- 21. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pneuma .

- 22.Ghasemzadeh N, Zafari AM. A brief journey into the history of the arterial pulse. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:164832. doi: 10.4061/2011/164832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajar R. Past glories the great library of Alexandria. Heart Views. 2000;1:278–82. [Google Scholar]