Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of a model OA consultation for OA to support self-management compared with usual care.

Methods

An incremental cost–utility analysis using patient responses to the three-level EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D) questionnaire was undertaken from a UK National Health Service perspective alongside a two-arm cluster-randomized controlled trial. Uncertainty was explored through the use of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.

Results

Differences in health outcomes between the model OA consultation and usual care arms were not statistically significant. On average, visits to the orthopaedic surgeon were lower in the model OA consultation arm by −0.28 (95% CI: −0.55, −0.06). The cost–utility analysis indicated that the model OA consultation was associated with a non-significant incremental cost of £−13.11 (95% CI: −81.09 to 54.85) and an incremental quality adjusted life year (QALY) of −0.003 (95% CI: −0.03 to 0.02), with a 44% chance of being cost-effective at a threshold of £20 000 per QALY gained. The percentage of participants who took time off and the associated productivity cost were lower in the model OA consultation arm.

Conclusion

Implementing National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines using a model OA consultation in primary care does not appear to lead to increased costs, but health outcomes remain very similar to usual care. Even though the intervention seems to reduce the demand for orthopaedic surgery, overall it is unlikely to be cost-effective.

Keywords: primary care, cost-effectiveness, NICE osteoarthritis guidelines, ICECAP, EQ-5D, implementation

Rheumatology key messages

Using a model OA consultation in primary care does not lead to increased costs.

The model OA consultation appears to reduce referrals to orthopaedic surgery.

The model OA consultation is unlikely to be cost-effective.

Introduction

OA is most prevalent in older people and is known to adversely affect quality of life [1–3]. Estimates from the United States of America (USA) suggest that 12.4 million adults over the age of 65 years are living with this condition and around 2.9 million people have a disabling form of OA. A report by the Royal College of General Practitioners indicates that about 1 million adults consult with symptoms of OA in a year and it is one of the main reasons why people seek medical care [4–6]. The total healthcare cost of OA has been estimated at £1 billion in the UK [5]. Therefore OA places a considerable burden on scarce healthcare resources. The proportion of older people in the population has been increasing over time [7], and with this ageing population, it is expected that the prevalence of conditions such as OA will rise. A number of published guidelines have been developed to aid the treatment and management of OA [8–12]. In the UK, for example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that patients with OA should be offered core treatments when they first present in primary care. These include education and access to information, advice on local muscle strengthening exercise and general aerobic fitness, and if appropriate, advice on losing weight [12]. However, there is a gap between the care that is recommended and that which patients actually receive, and the core aspects of assessment and management of OA currently delivered in primary care do not meet the recommendations of these guidelines [13, 14]. Therefore, measures need to be put in place to ensure that resources are used optimally. Consequently, there was a need to develop a practical approach that could potentially support self-management of OA and also aid the implementation of the core NICE guidelines for OA. This led to the development of a model OA consultation [15] for older patients presenting with peripheral joint pain, and training for health care professionals to support its delivery. The model OA consultation integrated core recommendations from NICE and consisted of an OA guidebook written by patients and health professionals for patients, an enhanced initial consultation with a general practitioner (GP), and subsequent follow-up with a practice nurse (up to four consultations) in a dedicated nurse-led OA clinic. In addition a practice e-template was developed to record quality measures of care derived from a systematic review of quality indicators for OA [15, 16]. The Management of OsteoArthritis in Consultations (MOSAICS) trial compared the model OA consultation with usual care over a 12-month period. This paper reports the economic evaluation alongside the MOSAICS trial to assess the cost-effectiveness of the model OA consultation compared with usual care in patients who consult with OA.

Methods

The economic evaluation was conducted alongside a two-arm prospective pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial in eight general practices in Cheshire, Shropshire and Staffordshire, UK. The protocol has been previously published [15]. The eight practices were randomized to receive either the model OA consultation or usual care (control). Additional details of the intervention can be found in the supplementary data, section on the model OA consultation and supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online. The trial on which the present study is based was approved by the North West 1 Research Ethics Committee, Cheshire (REC reference: 10/H1017/76) and was monitored by an Independent Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee (Trial registration number ISRCTN06984617); no additional ethical approval was required for this study.

The primary outcome measure for the trial was the 12-item Short Form (SF-12) physical component score [17]. The health economic analysis initially took the form of a cost–consequence analysis where a description of all the important results relating to costs and consequences [(clinical outcomes, EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D), Short Form Six Dimension (SF-6D), ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults (ICECAP-A)] were reported. Subsequently, an incremental cost–utility analysis using the quality adjusted life year (QALY) as an outcome measure was undertaken from a UK National Health Service (NHS) perspective.

Data collection

Resource use and costs

Information on resource use and time off work due to joint problems was collected from the postal MOSAICS consultation questionnaires completed by participants at 6 and 12 months’ follow-up. NHS costs included primary and secondary care contacts, investigations, medication and contacts with other health care professionals such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Questions on participant’s personal expenditure focused on private health care use and over-the-counter treatments [15].

In order to value resource use, unit costs were obtained from standard sources such as the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care [18], the British National Formulary [19] and NHS Reference Costs [20] and applied to resource use data. Due to the lack of nationally representative unit cost estimates for private health care, this care was costed as the NHS equivalent. To obtain the cost of the model OA consultation, information on the resources used to deliver the intervention was obtained from patient records collected throughout the trial. To generate the intervention cost, we obtained records collected as part of the intervention. These records showed that the average number of times that trial participants actually saw their nurse from available records was 2.3. We therefore made the assumption that everyone in the intervention arm who actually saw the nurse did so at least 2.3 times. GP costs were not included as part of the intervention since all participants, irrespective of trial intervention arm received usual care. Costs associated with over-the-counter medication were based on participant responses to the postal questionnaires. Unit costs of the resource use items are presented in supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online, and are in 2012–13 prices.

Health and quality of life outcomes

All participants completed the three-level version of the EQ-5D questionnaire [21] at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months. EQ-5D index scores were generated using the UK value set [22] to calculate QALYs over the 12-month period, which was used in the base case analysis. (The QALY is an outcome measure that takes into account both the quality and quantity of life associated with an intervention). Participants also completed the SF-12 questionnaire [17], which was used to generate SF-6D scores [23], and the ICECAP-A questionnaire at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months. The ICECAP-A is a measure of capability for adults, which aims to capture an individual’s freedom to function in five key areas of their life: attachment, autonomy, enjoyment, stability and achievement [24].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the main health economic outcomes (EQ-5D, SF-6D and ICECAP-A). The cost–utility analysis was focused on determining the difference in costs and QALYs between the model OA consultation and usual care arms. To ensure all eligible participants were included in the study, missing EQ-5D, SF-6D, ICECAP-A and costs were imputed using multiple imputation methodology [25]. An imputation model was fitted and included 25 imputed datasets. Using EQ-5D scores, QALYs over a 12-month time period were calculated for each study participant with the area under the curve method [26]. Imbalances in baseline utility (EQ-5D) scores between the model OA consultation and usual care arms were controlled for using a multiple linear regression approach [27]. Mean costs associated with each trial arm were estimated, and due to the skewed nature of the costs, the difference in mean costs and 95% CIs were calculated using non-parametric bootstrapping [28]. Net monetary benefit (ΔE × λ – ΔC) was also estimated for each participant. This is defined as the change in effectiveness/QALYs (ΔE) multiplied by the cost-effectiveness threshold (λ) minus the change in cost (ΔC) [29]. The threshold value (λ) used for the estimation of net benefits was £20 000 per QALY.

The base case took the form of a cost–utility analysis from a NHS perspective and was conducted using multilevel linear modelling (as participants are clustered within GP practices), a method that has been recommended for the economic evaluation of cluster trials [30]. The dependent variables were net monetary benefits, costs, QALYs and cost of work absence. Independent variables included gender and baseline EQ-5D. Model estimates of the difference in costs, QALYs and net monetary benefits were used to derive an incremental cost per QALY gained and an incremental net monetary benefit.

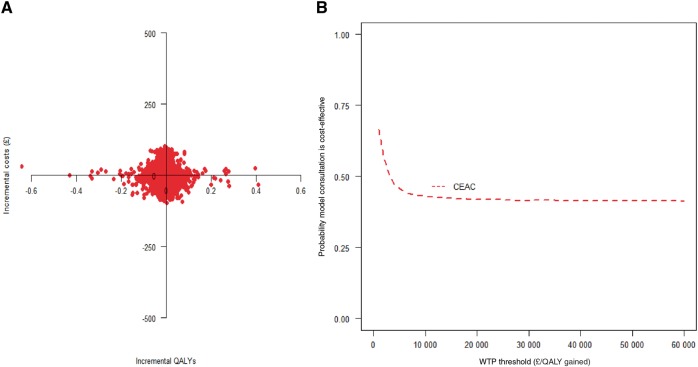

Uncertainty was explored through the use of cost-effectiveness planes and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves; these plot the probability that the intervention is cost-effective against willingness to pay threshold values [31]. All analyses were carried out in Stata 12, Realcom and Microsoft Excel [32–34]. Discounting was not required as the follow-up period was 12 months.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis had two main foci. The first was to explore uncertainties in the trial-based data by using QALYs generated from the SF-6D to obtain cost-effectiveness estimates. The second was to explore broader societal costs through the inclusion of private health care costs, for example, over-the-counter medication costs and private health care utilization costs as well as productivity costs. The human capital approach [35], was used to estimate productivity costs using data collected on employment status at every time point and days off work due to health. The average wage for each respondent was identified using UK Standard Occupational Classification coding and annual earnings data for each job type [36].

Results

A total of 525 participants across the eight randomized practices were recruited to the cluster trial. Of these, 288 participants were in the practices randomized to the model OA consultation arm and 237 in practices randomized to the usual care arm. The mean (s.d.) age across all patients was 67.3 years (10.4) and 59.5% were female. Follow-up rates at 6 and 12 months were 424 (81%) and 384 (73%), respectively, in the intervention and control arms. A total of 305 (58.1%) participants provided complete EQ-5D data at all time points.

Resource use

Primary care visits were generally higher in the usual care arm. Although the differences were not statistically significant, participants in the usual care arm had more visits to both the GP and the nurse. There was no significant difference in secondary care visits between trial arms with the exception of visits to the orthopaedic surgeon, which was significantly higher in the usual care arm. Approximately 65% of participants in the usual care arm had prescribed medication as compared with 59% in the model OA consultation arm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Resource use over 12-months (complete cases)

| Resource use category | Model OA consultation (n = 199) | Usual care (n = 155) | Difference (bootstrapped 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care visitsa | 1.52 (2.46) | 1.99 (3.38) | −0.48 (−1.18, 0.13) |

| GP at practice | 1.32 (2.11) | 1.59 (2.62) | −0.28 (−0.78, 0.24) |

| GP at home | 0.02 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.01 (−0.11, 0.03) |

| Nurse at practice | 0.19 (0.67) | 0.39 (1.29) | −0.20 (−0.48, −0.01) |

| Nurse at home | 0 | 0.01 (0.08) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0) |

| Other healthcare professionals (attached to practice)b | 0.21 (0.86) | 0.32 (1.15) | −0.12 (−0.33, 0.11) |

| Secondary care visitsc | 1.11 (2.65) | 1.43 (2.91) | −0.32 (−0.96, 0.27) |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 0.34 (0.89) | 0.58 (1.37) | −0.24 (−0.52, −0.003) |

| Podiatrist | 0.13 (0.92) | 0.12 (0.80) | 0.003 (−0.17, 0.17) |

| Physiotherapist | 0.61 (2.01) | 0.65 (1.93) | −0.04 (−0.47, 0.36) |

| Occupational therapist | 0.04 (0.21) | 0.07 (0.58) | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.04) |

| Other secondary care visitsb | 0.16 (0.91) | 0.10 (0.51) | 0.06 (−0.07, 0.24) |

| Private consultantsd | 0.39 (1.66) | 0.57 (3.07) | −0.18 (−0.79, 0.29) |

| Private other health care professionalsb | 0.13 (0.85) | 0.04 (0.28) | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.23) |

| Hospital investigations/treatmentsb,e, n (%) | 82 (41.21) | 72 (46.45) | 10 |

| Prescribed drugsb,e, n (%) | 117 (58.79) | 101 (65.16) | 16 |

| Over-the-counter drugsb,e, n (%) | 98 (49.25) | 72 (46.45) | 26 |

All figures are means (s.d.) except where indicated. Resource use items presented in this table were solely obtained from self-report questionnaires.

Includes contacts with GP and nurse at home and practice.

Patient-specific.

Includes contacts with physiotherapists, occupational therapists podiatrists and orthopaedic surgeons.

Includes contacts with private physiotherapists, occupational therapists private podiatrists and private orthopaedic surgeons.

Figures are the number of patients (per cent) who stated that they had an investigation or a drug. GP: general practitioner.

Health outcomes

Mean EQ-5D and SF-6D scores increased at all time points over the 12-month period in both the intervention and usual care arms indicating an improvement in health status over time. Although these scores were higher in the usual care arm, the differences were not statistically significant. When total QALYs were estimated, the usual care arm was associated with marginally higher overall QALYs (in respect to both the EQ-5D and SF-6D). Also, the results for the between-group differences in ICECAP-A showed similarly that the usual care arm showed slightly higher average levels of capability across follow-up (Table 2). EQ-5D scores were generally lower than SF-6D scores at all times.

Table 2.

Health outcomes over 12 months (imputed analysis)

| Health outcome | Model OA consultation (n = 288) | Usual care (n = 237) | Difference (bootstrapped 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D scores | |||

| Baseline | 0.573 (0.298) | 0.588 (0.272) | −0.015 (−0.062, 0.039) |

| Month 3 | 0.615 (0.280) | 0.631 (0.264) | −0.016 (−0.064, 0.030) |

| Month 6 | 0.637 (0.264) | 0.638 (0.259) | −0.001 (−0.044, 0.044) |

| Month 12 | 0.651 (0.262) | 0.674 (0.224) | −0.023 (−0.067, 0.018) |

| QALYs | 0.627 (0.244) | 0.639 (0.224) | −0.012 (−0.054, 0.026) |

| QALYsa | 0.632 | 0.634 | −0.002 (−0.25, 0.020) |

| QALYsb | −0.003 (−0.026, 0.197) | ||

| SF-6D scores | |||

| Baseline | 0.678 (0.139) | 0.690 (0.148) | −0.012 (−0.037, 0.013) |

| Month 3 | 0.688 (0.141) | 0.696 (0.141) | −0.008 (−0.033, 0.017) |

| Month 6 | 0.687 (0.142) | 0.707 (0.144) | −0.020 (−0.044, 0.004) |

| Month 12 | 0.693 (0.139) | 0.702 (0.138) | −0.009 (−0.032, 0.015) |

| QALY | 0.688 (0.128) | 0.701 (0.129) | −0.013 (−0.038, 0.010) |

| QALYa | 0.692 | 0.696 | −0.004 (−0.03, 0.01) |

| QALYsb | −0.012 (−0.03, 0.01) | ||

| ICECAP-A | |||

| Baseline | 0.826 (0.166) | 0.851 (0.155) | −0.025 (−0.053, 0.003) |

| Month 3 | 0.828 (0.151) | 0.853 (0.155) | −0.025 (−0.053, 0.001) |

| Month 6 | 0.821 (0.160) | 0.843 (0.158) | −0.022 (−0.049, 0.005) |

| Month 12 | 0.837 (0.153) | 0.846 (0.155) | −0.009 (−0.038, 0.014) |

All figures are means (s.d.) unless otherwise indicated.

Adjusted for baseline Utility.

Difference in QALYs between trial arms adjusted for baseline utility and gender (regression model). EQ-5D: EuroQoL-5D; ICECAP-A: ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults; QALY: quality adjusted life year; SF-6D: Short Form Six Dimension.

Costs

Overall NHS and health care costs were also higher in the usual care group compared with the model OA consultation arm. However, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 3). Table 3 also gives a breakdown of costs for each intervention. Use of primary and secondary care, including visits to the orthopaedic surgeon, was greater in the usual care arm leading to higher costs.

Table 3.

Per patient costs over 12 months (in pounds)

| Resource use category | Model OA consultation | Usual care | Difference (bootstrapped 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 199), £ | (n = 155), £ | ||

| Primary care visitsa | 56.01 (83.53) | 69.02 (103.31) | −13.01 (−35.24, 5.28) |

| GP at practice | 44.76 (71.80) | 54.18 (89.01) | −9.42 (−29.03, 7.41) |

| GP at home | 0.81 (6.55) | 0.35 (4.31) | 0.46 (−0.71, 1.55) |

| Nurse at practice | 2.11 (7.46) | 4.61 (15.07) | −2.49 (−5.50, −0.03) |

| Nurse at home | 0 | 0.15 (1.87) | (−0.54, 0) |

| Other primary care visitsb | 8.33 (24.20) | 9.74 (29.72) | −1.41 (−7.37, 3.97) |

| Secondary care visitsc | 60.68 (130.42) | 76.48 (156.38) | −15.80 (−51.40, 14.01) |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 27.09 (71.66) | 44.31 (106.94) | −17.22 (−37.95, 1.18) |

| Podiatrist | 5.32 (35.65) | 4.34 (26.23) | 0.98 (−5.03, 7.93) |

| Physiotherapist | 21.55 (77.01) | 21.74 (70.72) | −0.18 (−15.47, 16.50) |

| Occupational therapist | 2.06 (11.98) | 2.24 (16.93) | −0.18 (−3.50, 2.61) |

| Other secondary care visitsb | 4.67 (17.85) | 3.85 (22.67) | 0.81 (−4.45, 4.65) |

| Hospital investigations/treatmentsb | 109.71 (401.16) | 92.36 (222.66) | 17.35 (−42.40, 83.75) |

| Prescribed drugsb | 15.51 (20.34) | 15.65 (21.47) | −0.14 (−4.58, 3.86) |

| Trial intervention cost | 11.47 (20.69) | 0 | 11.47 (8.69, 14.42) |

| Over-the-counter drugsb | 27.14 (255.67) | 27.93 (121.01) | −0.79 (−31.51, 50.14) |

| Private health professionalsb | 21.62 (76.54) | 29.53 (135.05) | −7.91 (−39.24, 12.24) |

| Imputed analysis | (n = 288) | (n = 237) | |

| Total NHS costsd | 227.17 (411.84) | 236.11 (345.35) | −8.94 (−71.79, 57.70) |

| Total Healthcare costsd | 278.56 (535.43) | 285.99 (400.43) | −7.43 (−76.41, 76.26) |

All figures are means (s.d.) unless otherwise indicated.

Includes contacts with GP and nurse at home and practice.

Patient-specific.

Includes contacts with physiotherapists, occupational therapists, etc.

Unadjusted costs. GP: general practitioner.

Cost-effectiveness

Estimates from the regression model show that the intervention was associated with a lower cost (P = 0.705) and fewer QALYs (P = 0.786) (Table 4). At a willingness to pay threshold of £20 000 per QALY, the model OA consultation was associated with a 44% chance of being cost-effective (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Base case cost–utility analysis (imputed analysis)

| Outcome | Difference in mean (intervention − control)a | P-value | CI | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS costsb, £ | −13.11 | 0.705 | −81.09, 54.85 | Intervention less costly and less effective. |

| QALYsb | −0.003 | 0.786 | −0.03 , 0.02 | |

| Net monetary benefitsb, £ | −33.63 | 0.887 | −497.56, 430.30 |

Difference in mean per patient cost and QALYs between trial arms. bAdjusted for baseline utility and gender. NHS: National Health Service; QALY: quality adjusted life year.

Fig. 1.

Cost-effectiveness plane (model consultation vs control) (A) and CEAC (model consultation vs control) (B)

WTP: willingness to pay.

Sensitivity analysis

When broader health care costs were used, the intervention was still less costly (P = 0.768) and less effective (P = 0.786) than the usual care arm (Table 5). Cost–utility analysis with QALYs generated from the SF-6D yielded similar results to the base case analysis, that is, the intervention was less costly (P = 0.705) and less effective (P = 0.187) than the usual care (Table 5). A total of 136 participants were in full-time employment at baseline. Of these, 40 participants, 20 in each trial arm, took time off over the 12-month period. Those in the intervention arm had fewer mean days off work than those in the usual care arm (P = 0.364). The associated productivity-related cost was lower in the intervention arm, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis

| Sensitivity analysis scenario and outcomes | Difference in mean (intervention − control)a | P-value | CI | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost–utility analysis with SF-6D | ||||

| NHS costsb, £ | −13.11 | 0.705 | −81.09, 54.85 | Intervention less costly and less effective |

| QALYs (SF-6D)b | −0.012 | 0.187 | −0.03 , 0.01 | |

| Net monetary benefitsb, £ | −178.39 | 0.362 | −561.74 , 204.96 | |

| Cost–utility analysis with health care costs | ||||

| Health care costsb, £ | −14.14 | 0.768 | −108.08, 79.80 | Intervention less costly and less effective |

| QALYsb | −0.003 | 0.786 | −0.03, 0.02 | |

| Net monetary benefitsb, £ | −34.95 | 0.883 | −501.82, 431.92 | |

| Time off work and productivity costs | ||||

| Number of days off over 12 monthsb | −1.05 | 0.364 | −3.35, 1.23 | |

| Mean cost of work absenceb, £ | −23.25 | 0.845 | −256.32, 209.83 | |

Difference in mean per patient costs net benefits, QALYs and time off work between trial arms.

Adjusted for baseline utility, and gender (regression model). NHS: National Health Service; QALY: quality adjusted life year.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This study sought to assess the cost-effectiveness of the model OA consultation for the implementation of NICE guidelines and support for self-management of OA in primary care. Our results reveal that there was a general increase in health status across the whole population as measured by the EQ-5D and SF-6D over the 12-month period, and although scores were slightly higher in the usual care arm, the difference was not statistically significant. SF-6D scores were higher than EQ-5D scores, a result which was in line with a previous study [37]. With the exception of visits to the orthopaedic surgeon, which was higher in the usual care group, there were no significant differences in all other secondary care resource use items between the trial arms. Participants in the usual care arm also reported more time off work compared with the intervention arm. The finding that the intervention may lead to reduced referrals and less time off work suggests a possible avenue for future research to identify individual patients who might benefit from the approach.

The model OA consultation was less expensive than usual care and although this was not statistically significant, one might argue that the exclusion of the cost of training resulted in this lower cost. However, it should be noted that there are difficulties associated with the estimation of a per patient training cost within economic evaluation studies and also training received would be used for a large number of patients over a number of years, resulting in a low mean cost per patient.

The cost–utility analysis showed that the model OA consultation was less costly but less effective than usual care. Even though these differences are not statistically significant, the established approach that is used in health economics is to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis, focusing on the joint estimation of costs and outcomes [38]. At a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000 per QALY, the probability of the model OA consultation being cost-effective was low at 44%.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A major strength of this study is that it is the first to consider the cost-effectiveness of the model OA consultation for the implementation of NICE guidelines and support for self-management of OA in primary care. Second, the study considered cost-effectiveness in a population consulting with peripheral joint pain and OA in primary care. Much of the cost-effectiveness studies for OA are based on studies of knee OA and, as such, our study considered a population where evidence of cost-effectiveness is lacking. Third, this study considered multiple outcomes and also considered outcomes broader than just health-related quality of life, which distinguishes it from other health economic evaluations, which consider a single outcome measure. This study also has some limitations. First is the fact that the main outcome for the health economic analysis was the three-level EQ-5D, which may not be sensitive to changes in this disease area [39]. The five-level version of the EQ-5D [40] is now available and this is likely to be more sensitive to change. Second, the difficulty associated with the estimation of a per-patient training cost led to the exclusion of this cost from the analysis.

Meaning of the study

Implementing NICE guidelines using a model OA consultation in primary care may not lead to increased costs. Although the intervention may support some people with OA to remain in work and reduce the demand for orthopaedic surgery, overall it is unlikely to be cost-effective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The project was undertaken with the support of Keele Clinical Trials Unit, Keele University, UK.

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grant (RP-PG-0407-10386) and the Arthritis Research UK Centre in Primary Care grant (Grant Number 18139). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Disclosure statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1. Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P.. Disabling knee pain – another consequence of obesity: results from a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2006;6:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D. et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray CJ, Richards MA, Newton JN. et al. UK health performance: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2013;381:997–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of General Practitioners—Birmingham Research Unit. Annual prevalence report. Technical Report. 2006. London, United Kingdom: Royal College of General Practitioners.

- 5. Chen A, Gupte C, Akhtar K, Smith P, Cobb J.. The global cost of osteoarthritis: how the UK compares. Arthritis 2012;2012:698709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jordan KP, Joud A, Bergknut C. et al. International comparisons of the consultation prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions using population-based healthcare data from England and Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;73:212–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office for National Statistics. Statistical Bulletin: Estimates of the very old (including centenarians) for the United Kingdom, 2002-2012. 2014. London: Office for National Statistics. www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_357100.pdf (21 September 2017, date last accessed).

- 8. Altman RD, Hochberg MC, Moskowitz RW, Schnitzer TJ.. Recommendations for the medical management of OA of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1905–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M. et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee OA: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1145–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G. et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee OA, Part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoathr Cartil 2007;15:981–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conaghan PG, Dickson J, Grant RL.. Care and management of OA in adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2008;336:502–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis: Care and Management in Adults. London: NICE, 2014. www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG177 (21 September 2017, date last accessed).

- 13. Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C in collaboration with the Primary Care Rheumatology Society. Primary care treatment of knee pain a survey in older adults. Rheumatology 2007;46:1694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steel N, Bachmann M, Maisey S. et al. Self reported receipt of care consistent with 32 quality indicators: national population survey of adults aged 50 or more in England. BMJ 2008;337:a957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dziedzic K, Healey E, Porcheret M. et al. Implementing the NICE osteoarthritis guidelines a mixed methods study and cluster randomised trial of a model osteoarthritis consultation in primary care. The Management of OsteoArthritis In ConsultationS (MOSAICS) study protocol. Implement Sci 2014;9:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edwards JJ, Khanna M, Jordan KP. et al. Quality indicators for the primary care of osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;74:490–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD.. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey. Construction of scales and prelimnary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Curtis L. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2012 PSSRU. Canterbury: University of Kent, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. BMJ Group. British National Formulary (BNF) 66. London: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health. NHS Reference Costs 2012-13. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-2012-to-2013 (21 September 2017, date last accessed).

- 21. Rabin R, de Charro F.. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brazier JE, Roberts J.. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care 2004;42:851–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Al-Janabi H, Flynn T, Coast J.. Development of a self-report measure of capability wellbeing for adults: the ICECAP-A. Qual Life Res 2012;21:167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gomes M, Diaz-Ordaz K, Grieve R, Kenward RG.. Multiple imputation methods for handling missing data in cost-effectiveness analysis that use data from hierarchical studies: an application to cluster randomised trials. Med Dec Making 2013;33:1051–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mathews JN, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P.. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ 1990;300:230–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manca A, Hawkins N, Sculpher MJ.. Estimating mean QALYs in trial based cost effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ 2005;14:487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Briggs AH, Gray AM.. Handling uncertainty when performing economic evaluation of health care interventions. Health Technol Assess 1999;3:1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'brien BJ, Stoddart GL.. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.[WorldCat] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gomes M, Ng ES, Grieve R.. Developing appropriate methods for cost-effectiveness analysis of cluster randomised trials. Med Dec Making 2012;32:350–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Van Hout B, Al MJ, Gordon GS, Rutten FFH.. Costs, effects and C/E ratios alongside a clinical trial. Health Econ 1994;3:309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.StataCorp. LP. Stata/IC 12.1 for Windows. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp, 2012.

- 33. Carpenter JR, Goldstein H, Kenward G.. REALCOM-IMPUTE software for multilevel multiple imputation with mixed responses types. J Stat Soft 2011;45:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Microsoft Excel for Windows 2010. Redmond, WA, USA: Microsoft, 2010.

- 35. Sculpher M. The role and estimation of productivity costs in economic evaluation In: Drummond MF, McGuire A, eds. Economic Evaluation in Health Care: Merging Theory with Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: 94–112. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Office for National Statistics. Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). London: Office for National Statistics, 2000. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/classifications/archived-standard-classifications/standard-occupational-classification-2000/about-soc-2000/index.html (21 September 2017, date last accessed).

- 37. Whitehurst DG, Bryan S.. Another study showing that two preference based measures of health-related quality of life (EQ-5D and SF-6D) are not interchangeable. But why should we expect them to be. Value Health 2011;14:531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Briggs AH, O’Brien BJ.. The death of cost-minimisation analysis? Health Econ 2001;10:179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brazier JE, Harper R, Munro J, Walters SJ, Snaith ML.. Generic and condition-specific outcome measures for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology 1999;38:870–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A. et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.