Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether demographic, socioeconomic, and reproductive health characteristics affect long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) use differently by race-ethnicity. Results may inform the dialogue on racial pressure and bias in LARC promotion.

Study design

Data derived from the 2011–2013 and 2013–2015 National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG). Our study sample included 9321 women aged 15–44. Logistic regression analyses predicted current LARC use (yes vs. no). We tested interaction terms between race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic) and covariates (for example, education, parity, poverty level) to explore whether their effects on LARC use vary by race-ethnicity.

Results

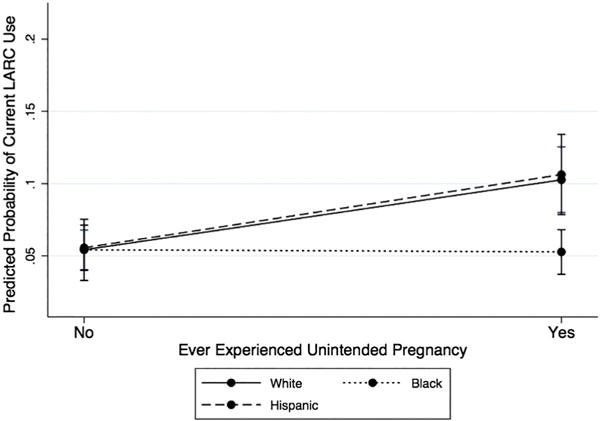

In the race-interactions model, data did not show that low income and education predict LARC use more strongly among Black and Hispanic women than among White women. There was just one statistically significant race-interaction: experience of unintended pregnancy (p=.014). Among Whites and Hispanics, women who reported ever experiencing an unintended pregnancy had a higher predicted probability of LARC use than those who did not. On the other hand, among Black women, the experience of unintended pregnancy was not associated with a higher predicted probability of LARC use.

Conclusions

With the exception of the experience of unintended pregnancy, findings from this large, nationally representative sample of women suggest similar patterns in LARC use by race-ethnicity.

Implications

Results from this analysis of NSFG data do not provide evidence that observed differences in LARC use by race-ethnicity represent socioeconomic disparities, and may assuage some concerns about reproductive coercion among women of color. Nevertheless, it is absolutely critical that providers use patient-centered approaches for contraceptive counseling that promote women’s autonomy in their reproductive health care decision-making.

Keywords: Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), Race/ethnicity, Disparities, NSFG

1. Introduction

Although the unintended pregnancy rate in the United States has fallen markedly in the last several years, racial and ethnic disparities persist [1]. Black and Hispanic women are about twice as likely as White women to experience an unintended pregnancy each year: 79 and 58, respectively, vs. 33 per 1000 women of reproductive age [1]. For many women who wish to delay or prevent pregnancy, long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) are an attractive option. LARC devices – the intrauterine device [IUD] and hormonal subdermal implant – are the most effective non-permanent methods on the market today [2]. They are safe for nearly all patients and are cost-effective if in place for at least 1–2 years [3,4]. Importantly, women tend to think highly of them: both devices exhibit high satisfaction and continuation rates [5]. LARC devices have surged in popularity in the last several years [6]. In 2008, only 6.5% of contraceptive users used a LARC device, compared to 15% in 2014 [6].

Recent rates of LARC use are similar by race: among current contraceptive users, 18% of Hispanic women, 13% of White women, and 15% of Black women reported using LARC [6]. While women of color may be statistically as likely to use LARC as White women [6], advocates of reproductive justice remain deservedly vigilant about preventing LARC-related coercion among poor women of color [7,8], given the complex and often coercive U.S. history of contraception and sterilization for these women [9,10]. Indeed, a recent analysis of young women ages 18–19 showed that although White contraceptive users spent more time than Black women using some of the more effective methods (oral contraceptive pill, transdermal patch, and vaginal ring), Black women spent more time than White women using LARC [11]. This pattern may indicate a unique racial profile for LARC use. Qualitative research suggests that compared to White women, women of color may perceive more provider pressure to use LARC [12]. Further, a randomized controlled trial found that providers were more likely to recommend IUDs to poor African American women than to poor White women [13].

Given these concerns about inappropriate LARC promotion among women of color, our first and primary study aim was to use a nationally representative dataset to investigate whether measured demographic, socioeconomic, and reproductive health characteristics affect LARC use differently by race and ethnicity. In contrast to the prior literature, which tends to treat race as a control variable, in the present study we use race-interaction terms to explore whether individual characteristics affect LARC use differently by race and ethnicity. Such an approach could identify important intersectional effects and inform our understanding of observed racial-ethic differences in LARC use. For example, if the association between socioeconomic factors and LARC use differs by race, it may indicate that observed racial differences in LARC use are associated with structural inequities (i.e., disparities). On the other hand, race-interactions between reproductive health factors and LARC use may suggest differences in patient needs and preferences (i.e., differences).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data source

We pooled the 2011–2013 and 2013–2015 waves of the NSFG, and used this combined dataset covering 2011–2015 in our analyses. The NSFG collects data on an extensive array of topics related to sexual and reproductive health and employs multi-stage probability-based sampling to achieve a nationally representative sample of the U.S. household population between the ages of 15 and 44 [14]. The University of Wisconsin—Madison’s Institutional Review Board includes NSFG as a publicly available de-identified dataset that is exempt from review.

2.2. Study population

The study population included non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic women of reproductive age (15–45). We excluded women of other races and those who were multiracial (n=1081) due to small sample sizes for the specific groups. We excluded women who were currently pregnant (n=446) or trying to conceive (n=452), as these women would not be potential current contraceptive users. We did not exclude women based on lack of sexual activity because IUDs and implants are long-acting and used continuously; thus, women may use these methods even if they are not currently sexually active. The final analytic sample included 9321 women (4655 White, 2070 Black, and 2596 Hispanic).1

2.3. Study variables

The outcome variable was current LARC use (yes vs. no). Given the small number of implant users (n=140), we combined IUD and implant users into one LARC category. Our primary covariate was race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Hispanic). Covariates were similar to those used in prior literature on patterns in use of LARC and other contraceptives, including work focused on racial and ethnic differences [11,15–18]. These covariates included demographic characteristics (age, religion, and marital status), socioeconomic characteristics (poverty level, education, and current health insurance) and reproductive health characteristics (parity, intent for [future] children, number of partners in the past year, and experience of unintended pregnancy (mistimed or unwanted). We also adjusted for 2011–2013 vs. 2013–2015 wave of the NSFG.

2.4. Statistical analysis

First, chi-squared tests assessed differences in the distribution of demographic, socioeconomic, and reproductive health characteristics by race and LARC use. Then unadjusted logistic regression analyses predicted current LARC use with each covariate individually. Covariates were then entered into an adjusted logistic regression model predicting current LARC use. We entered covariates in three blocks: Model 1 included demographic characteristics, Model 2 added socioeconomic characteristics, and Model 3 added reproductive health characteristics.

We then moved to modeling LARC use with race-interaction terms. We chose to examine interaction effects – when the effect of one variable on the outcome varies by level of another variable – because they allow us to examine whether variables have different effects on LARC use by race. In moving to the race-interaction terms model, we collapsed levels of a few variables – age, religion, and number of partners in the past year – to accommodate small cell sizes (n<15). We entered all variables into the adjusted model as both main effects and race-interaction terms. To ensure that any significant interaction terms were robust, we ran the model twice; first removing race-interaction terms with p-values less than .1, and then again removing those less than .05. Using this final iteration of the race-interaction model, we then calculated predicted probabilities of current LARC use, estimated at the mean values of the covariates for each racial/ethnic group. This type of estimation facilitates interpretation of findings as the likelihood that the “average” White, Black, or Hispanic woman will be using LARC.

To adjust for the complex sampling framework of the NSFG, all analyses used the “svy” commands in Stata SE software (version 15.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX). We also used the “subpop” option for subgroup analyses. All estimates we report are weighted to reflect the household population of women aged 15–44 in the U.S. [14].

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

LARC use differed significantly by race and ethnicity: 9% of White women, 11% of Hispanic women, and 7% of Black women reported currently using LARC (p=.03). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of LARC users. Overall, LARC users were more likely than non-LARC users to be older, married or cohabiting, and parous; to not intend (future) children; and to have experienced an unintended pregnancy (all pb.01). Among LARC users, White women had higher income and education than Black and Hispanic women and were also more likely to be married and privately insured (all pb.0001). Black LARC users – and Hispanic users, to a lesser extent – tended to be younger than White users (p=.0002).

Table 1.

Characteristics of current users of long-acting reversible contraceptives among US women aged 15–44, by race/ethnicity, National Survey of Family Growth, 2011–2015 [2011–2013 and 2013–2015 pooled] (n=9321).

| Percent of women who are LARC users | Characteristics of LARC users, by race | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=9321 |

Hispanic N=278 |

NH White N=444 |

NH Black N=167 |

P | ||||||

| N | (% users) | p | n | (col %) | n | (col %) | n | (col %) | ||

| Race | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 2596 | (10.7%) | 0.03 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Non-Hispanic White | 4655 | (9.5%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2070 | (7.1%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Age (y) | ||||||||||

| 15–19 | 1776 | (2.1%) | <.0001 | 9 | (2.3%) | 14 | (2.2%) | 17 | (15.1%) | .0002 |

| 20–24 | 1574 | (11.5%) | 69 | (25.7%) | 100 | (19.1%) | 41 | (20.8%) | ||

| 25–34 | 3271 | (13.7%) | 151 | (45.9%) | 206 | (48.5%) | 85 | (44.8%) | ||

| 35–45 | 2700 | (7.8%) | 49 | (26.1%) | 124 | (30.2%) | 24 | (19.3%) | ||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| No religion | 1978 | (9.2%) | 0.16 | 46 | (15.2%) | 133 | (26.4%) | 18 | (9.8%) | <.0001 |

| Catholic | 2162 | (8.3%) | 132 | (48.4%) | 58 | (11.7%) | 11 | (7.6%) | ||

| Protestant | 4676 | (9.6%) | 89 | (33.2%) | 217 | (52.4%) | 128 | (72.5%) | ||

| Other religions | 505 | (13.0%) | 11 | (3.2%) | 36 | (9.5%) | 10 | (10.2%) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 2598 | (12.5%) | <.0001 | 108 | (42.2%) | 191 | (54.8%) | 30 | (21.2%) | <.0001 |

| Cohabitating | 1220 | (13.6%) | 66 | (21.8%) | 86 | (19.7%) | 26 | (20.1%) | ||

| Neither married nor cohabiting | 5503 | (6.0%) | 104 | (36.0%) | 167 | (25.5%) | 111 | (58.7%) | ||

| Poverty level (% federal poverty level) | ||||||||||

| Less than 100% | 3274 | (9.2%) | 0.29 | 136 | (43.3%) | 105 | (19.9%) | 80 | (40.4%) | <.0001 |

| 100–199% | 2105 | (9.7%) | 79 | (26.0%) | 89 | (19.1%) | 41 | (27.2%) | ||

| 200–299 | 1418 | (11.0%) | 25 | (9.7%) | 93 | (24.1%) | 25 | (15.1%) | ||

| 300 + % | 2524 | (8.5%) | 38 | (21.1%) | 157 | (36.9%) | 21 | (17.4%) | ||

| Education | ||||||||||

| No high school degree | 2194 | (6.1%) | .003 | 70 | (27.6%) | 31 | (5.7%) | 28 | (17.1%) | <.0001 |

| High school degree | 2425 | (9.0%) | 82 | (24.4%) | 101 | (22.9%) | 54 | (24.0%) | ||

| Some college, no degree | 2073 | (10.6%) | 77 | (26.5%) | 102 | (23.6%) | 41 | (34.9%) | ||

| Associate’s degree | 719 | (12.8%) | 21 | (7.7%) | 49 | (11.5%) | 22 | (13.7%) | ||

| Bachelor’s or higher | 1910 | (10.2%) | 28 | (13.8%) | 161 | (36.2%) | 22 | (10.2%) | ||

| Current health insurance | ||||||||||

| Private | 4685 | (9.0%) | 0.51 | 93 | (40.0%) | 272 | (65.6%) | 71 | (44.8%) | <.0001 |

| Medicaid | 2283 | (9.8%) | 70 | (21.3%) | 84 | (15.0%) | 64 | (34.7%) | ||

| Other or none | 2353 | (10.1%) | 115 | (38.7%) | 88 | (19.4%) | 32 | (20.6%) | ||

| Parity | ||||||||||

| No live births | 4158 | (3.9%) | <.0001 | 34 | (10.5%) | 100 | (21.3%) | 25 | (17.9%) | .063 |

| 1 or 2 | 3436 | (15.9%) | 174 | (63.7%) | 275 | (59.9%) | 105 | (63.9%) | ||

| 3 or more | 1727 | (9.9%) | 70 | (25.9%) | 69 | (18.8%) | 37 | (18.3%) | ||

| Intention for (future) children | ||||||||||

| Intends/doesn’t know | 4776 | (8.2%) | .009 | 140 | (44.7%) | 188 | (38.4%) | 88 | (57.2%) | .015 |

| Does not intend | 4545 | (10.5%) | 138 | (55.3%) | 256 | (61.6%) | 79 | (42.9%) | ||

| Number partners in past year | ||||||||||

| 0 | 2294 | (2.8%) | <.0001 | 20 | (9.0%) | 29 | (5.8%) | 16 | (6.6%) | .36 |

| 1 | 5801 | (11.4%) | 228 | (82.1%) | 337 | (81.0%) | 113 | (74.3%) | ||

| 2 | 749 | (11.0%) | 17 | (6.7%) | 43 | (7.9%) | 24 | (12.1%) | ||

| 3 or more | 477 | (10.6%) | 13 | (2.3%) | 35 | (5.4%) | 14 | (7.0%) | ||

| Ever experienced unintended pregnancy | ||||||||||

| No | 5295 | (5.8%) | <.0001 | 80 | (27.7%) | 177 | (41.5%) | 46 | (30.8%) | .012 |

| Yes | 4026 | (14.6%) | 198 | (72.3%) | 267 | (58.5%) | 121 | (69.2%) | ||

| NSFG survey year | ||||||||||

| 2011–2013 | 4681 | (8.6%) | 0.12 | 140 | (47.8%) | 211 | (45.4%) | 82 | (42.8%) | .82 |

| 2013–2015 | 4640 | (10.2%) | 138 | (52.2%) | 233 | (54.6%) | 85 | (57.2%) | ||

Frequencies are raw and percentages are weighted to reflect the U.S. female civilian population. P-values are from chi-squared tests computed using the weighted data. “Private” health insurance includes private insurance and Medi-Gap; “Medicaid” includes Medicaid, CHIP, or a state-sponsored health plan; “Other or none” includes Medicare, military health care, other government health care, single-service plan only, Indian Health Service only, and not currently covered by health insurance. “Unintended pregnancy” refers to a mistimed or unwanted pregnancy.

3.2. Logistic regression models

Table A.1 shows unadjusted odds and adjusted odds (Models 1–3) from logistic regression models predicting current LARC use. Adjusted odds were substantively similar to unadjusted odds. In the final model, the associations between measured demographic, socioeconomic, and reproductive health factors largely did not differ by race and ethnicity (see Table 2). There was just one statistically significant race-interaction term: experience of unintended pregnancy (p=.014). To help interpret the significant interaction between race and unintended pregnancy, Fig. 1 shows predicted probabilities of LARC use by experience of unintended pregnancy (yes vs. no), separately by race. The “average” White woman and the “average” Hispanic woman each have about a 5% chance of using LARC if they have not experienced an unintended pregnancy and about a 10% chance if they have. However, the “average” Black woman has about a 5% chance of using LARC, regardless of whether or not she has experienced an unintended pregnancy.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds (final model) of current long-acting reversible contraceptive use among US women aged 15–44, National Survey of Family Growth, 2011–2015 [2011–2013 and 2013–2015 pooled] (n=9321).

| Adjusted Odds: Final Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| aOR | (95% CI) | |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 1.12 | (0.74, 1.68) |

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.14 | (0.70, 1.86) |

| Age (y) | ||

| 15–24 | 1.39 | (1.01, 1.91) |

| 25–34 | Ref | |

| 35–45 | 0.42 | (0.32, 0.56) |

| Religion | ||

| No religion | Ref | |

| Protestant | 1.04 | (0.76, 1.42) |

| Other religions | 1.04 | (0.77, 1.39) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.34 | (.99, 1.83) |

| Cohabitating | 1.44 | (1.02, 2.04) |

| Neither married nor cohabiting | Ref | |

| Poverty level (% federal poverty level) | ||

| Less than 100% | 1.05 | (0.74, 1.50) |

| 100–199% | 1.08 | (0.77, 1.51) |

| 200–299 | 1.20 | (0.88, 1.63) |

| 300 + % | Ref | |

| Education | ||

| No high school degree | 0.53 | (0.33, 0.86) |

| High school degree | 0.54 | (0.38, 0.77) |

| Some college, no degree | 0.79 | (0.58, 1.08) |

| Associate’s degree | .98 | (0.64, 1.50) |

| Bachelor’s or higher | Ref | |

| Current health insurance | ||

| Private | Ref | |

| Medicaid | 0.91 | (0.67, 1.25) |

| Other or none | 1.00 | (0.76, 1.31) |

| Parity | ||

| No live births | Ref | |

| 1 or 2 | 4.04 | (2.77, 5.89) |

| 3 or more | 2.50 | (1.54, 4.08) |

| Intention for (future) children | ||

| Intends/doesn’t know | Ref | |

| Does not intend | 1.08 | (0.82, 1.42) |

| Number partners in past year | ||

| 0 | Ref | |

| 1 | 2.01 | (1.29, 3.14) |

| 2 or more | 2.61 | (1.62, 4.20) |

| Ever experienced unintended pregnancy | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 2.00 | (1.37, 2.91) |

| Race × Ever experienced unintended pregnancy | ||

| Hispanic: Yes vs. No | 1.01 | (0.60, 1.69) |

| Black: Yes vs. No | 0.49 | (0.28, 0.85) |

| NSFG survey year | ||

| 2011–2013 | Ref | |

| 2013–2015 | 1.21 | (0.94, 1.55) |

Note: OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval. Results are weighted to reflect the U.S. female civilian population. “Private” health insurance includes private insurance and Medi-Gap; “Medicaid” includes Medicaid, CHIP, or a state-sponsored health plan; “Other or none” includes Medicare, military health care, other government health care, single-service plan only, Indian Health Service only, and not currently covered by health insurance.

Fig. 1.

Predicted probabilities of long-acting reversible contraceptive [LARC] use by history of unintended pregnancy, by race. Generated from the final model, predicted probabilities of LARC use are estimated at the mean values of the covariates [age, religion, marital status, poverty level, education, current health insurance, parity, intent for (future) childbearing, and number of partners in the past year] for each racial/ethnic group. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

In light of well-placed concerns about racial bias in LARC promotion [7,8], this study investigated whether demographic, socioeconomic, and reproductive health factors influence LARC use differently by race and ethnicity. Using a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. women, we found that, with the exception of experience of unintended pregnancy, associations between individual-level characteristics and LARC use did not differ by race and ethnicity. Our data do not show, for example, that low income and education are more strongly associated with LARC use for Black and Hispanic women than for White women. Based on these data, racial differences in LARC use do not appear to reflect social and economic inequalities by race, and may assuage some concerns about inappropriate LARC promotion among women of color. However, our analysis does not include measures of cultural or psychological factors that may influence patterns in LARC use by race.

Examination of the race × unintended pregnancy interaction demonstrates a potential opportunity to prevent recurrent unintended pregnancy among Black women who wish to use an effective contraceptive method. While White and Hispanic women were more likely to be using LARC if they had experienced an unintended pregnancy, among Black women, unintended pregnancy was not associated with LARC use. One potential explanation for these results is that the meaning of pregnancy intention may differ between White and Black women. For example, Kendall and colleagues argue that the idea of pregnancy planning may not be applicable to some low-income Black women because the traditional benefits of delaying pregnancy (such as career and marriage) are perceived as less attainable [19].

Another explanation may be that some Black women are responding to personal experiences of racial bias and pressure in family planning contexts [12,20–22]. Low-income Black women are more likely than middle-income White women to report being advised to limit their childbearing or discouraged from having children [20], and a randomized experiment of healthcare providers found them more likely to recommend IUDs to poor African American women than to poor White women [13]. For Black women, such experiences of racial bias and pressure in family planning settings may translate into negative perceptions of provider-dependent methods, like LARC [13,19–24]. For example, among female African American contraceptive users, stronger skepticism about contraceptive safety was associated with decreased odds of using a provider-dependent method [24].

These prior findings, suggesting warranted distrust of family planning providers among some Black women, indicate that there is great room for improvement in the way that providers deliver contraceptive care. Especially in the context of past reproductive injustice in the U.S., Black women deserve family planning providers in whom they trust, and who can provide contraceptive care sensitively and respectfully. Scholars have argued that successfully challenging reproductive injustice entails training providers to address their biases [7] and to use patient-centered approaches that place women’s wishes first in contraceptive care and method selection [7,8,25].

Strengths of the current study include its large, nationally-representative sample and the use of race-interaction terms to explore differences in patterns of LARC use by race and ethnicity. Limitations include the small sample of implant users, which prevents us from conducting separate analyses of IUD and implant users by race. Such analyses would be informative, as implant users may be more likely than IUD users to be Black, younger, and lower-income [15]. Finally, one statistical concern about using logistic procedures to compare effects across groups is that they assume that variation in the outcome arising from variables not included in the analysis is equal across the groups of study [26]. Although the NSFG covers a relatively expansive array of topics, we were not able to capture nuances that could help explain racial differences in contraceptive choice and use. To address this statistical concern, we re-ran our final adjusted model using linear probability modeling, which permits comparable effects across groups, but is more difficult to interpret than logistic regression [26]. We found similar results in both models, emphasizing the validity of our logistic results.

In conclusion, our results contribute to the literature on racial and ethnic differences in LARC use in that we found that only one characteristic affected LARC use differently by race: experience of unintended pregnancy. Nevertheless, it is of the utmost importance that clinicians and public health professionals promote LARC and other methods sensitively and responsibly, using patient-centered approaches that allow each contraceptive client to select a method that works for her. Ultimately, policies and programs are needed that will level the playing field of contraceptive care, giving all women the freedom to control their own fertility as they wish.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on this manuscript. Renee Kramer received travel support from the Master of Public Health Program, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin—Madison to present preliminary results of this study at the CityMatCH Leadership & MCH Epidemiology Conference in September 2016 in Philadelphia, PA. At the time of this study, Jenny Higgins was supported by grant K12 HD055894 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Table A.1.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds (Models 1–3) of current long-acting reversible contraceptive use among US women aged 15–44, National Survey of Family Growth, 2011–2015 [2011–2013 and 2013–2015 pooled] (n=9321).

| Unadjusted Odds | Adjusted Odds | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Model 1: aOR (95% CI) | Model 2: aOR (95% CI) | Model 3: aOR (95% CI) | |||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.14 | (0.90, 1.45) | 1.31 | (1.03, 1.68) | 1.29 | (0.98, 1.70) | 1.18 | (0.90, 1.55) |

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.73 | (0.57, 0.94) | 0.85 | (0.64, 1.13) | 0.81 | (0.61, 1.08) | 0.67 | (0.49, 0.91) |

| Age (y) | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 0.14 | (0.08, 0.22) | 0.20 | (0.12, 0.34) | 0.21 | (0.12, 0.37) | 0.73 | (0.40, 1.33) |

| 20–24 | 0.82 | (0.62, 1.09) | 1.01 | (0.77, 1.33) | 1.01 | (0.77, 1.33) | 1.54 | (1.13, 2.10) |

| 25–34 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 35–45 | 0.53 | (0.41, 0.69) | 0.51 | (0.39, 0.67) | 0.53 | (0.40, 0.69) | 0.43 | (0.32, 0.57) |

| Religion | ||||||||

| No religion | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Catholic | 0.90 | (0.66, 1.22) | 0.82 | (0.60, 1.14) | 0.83 | (0.61, 1.15) | 0.90 | (0.65, 1.23) |

| Protestant | 1.04 | (0.78, 1.40) | 1.10 | (0.80, 1.51) | 1.09 | (0.80, 1.49) | 1.06 | (0.78, 1.44) |

| Other religions | 1.47 | (0.98, 2.21) | 1.55 | (0.99, 2.41) | 1.54 | (0.99, 2.40) | 1.60 | (1.01, 2.55) |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 2.22 | (1.74, 2.83) | 1.92 | (1.46, 2.52) | 1.99 | (1.52, 2.61) | 1.31 | (0.97, 1.78) |

| Cohabitating | 2.46 | (1.88, 3.21) | 1.85 | (1.38, 2.47) | 1.84 | (1.38, 2.46) | 1.40 | (0.99, 1.98) |

| Neither married nor cohabiting | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Poverty level (% federal poverty level) | ||||||||

| Less than 100% | 1.09 | (0.84, 1.42) | 1.22 | (0.88, 1.70) | 1.03 | (0.72, 1.48) | ||

| 100–199% | 1.16 | (0.84, 1.59) | 1.24 | (0.90, 1.70) | 1.08 | (0.77, 1.50) | ||

| 200–299 | 1.32 | (1.00, 1.75) | 1.26 | (0.96, 1.66) | 1.18 | (0.87, 1.61) | ||

| 300 + % | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| No high school degree | 0.57 | (0.40, 0.83) | 0.87 | (0.53, 1.43) | 0.64 | (0.39, 1.05) | ||

| High school degree | .88 | (0.64, 1.19) | 0.83 | (0.59, 1.17) | 0.57 | (0.40, 0.82) | ||

| Some college, no degree | 1.04 | (0.78, 1.40) | 1.02 | (0.75, 1.37) | 0.81 | (0.60, 1.10) | ||

| Associate’s degree | 1.30 | (0.89, 1.89) | 1.22 | (0.83, 1.79) | 1.01 | (0.66, 1.53) | ||

| Bachelor’s or higher | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Current health insurance | ||||||||

| Private | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Medicaid | 1.10 | (0.86, 1.41) | 1.24 | (0.92, 1.68) | 0.91 | (0.66, 1.25) | ||

| Other or none | 1.14 | (0.88, 1.48) | 1.02 | (0.77, 1.34) | 0.97 | (0.74, 1.28) | ||

| Parity | ||||||||

| No live births | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 1 or 2 | 4.73 | (3.64, 6.15) | 3.64 | (2.54, 5.21) | ||||

| 3 or more | 2.74 | (1.99, 3.76) | 2.27 | (1.42, 3.62) | ||||

| Intention for (future) children | ||||||||

| Intends/doesn’t know | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Does not intend | 1.32 | (1.08, 1.63) | 1.09 | (0.83, 1.43) | ||||

| Number partners in past year | ||||||||

| 0 | 0.23 | (0.15, 0.34) | 0.54 | (0.34, 0.85) | ||||

| 1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 2 | 0.96 | (0.63, 1.45) | 1.25 | (0.80, 1.94) | ||||

| 3 or more | 0.93 | (0.64, 1.34) | 1.35 | (0.88, 2.08) | ||||

| Ever experienced unintended pregnancy | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 2.76 | (2.15, 3.53) | 1.84 | (1.37, 2.46) | ||||

| NSFG survey year | ||||||||

| 2011–2013 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 2013–2015 | 1.20 | (0.95, 1.50) | 1.21 | (0.95, 1.55) | ||||

Note: OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval. Results are weighted to reflect the U.S. female civilian population. The first column shows unadjusted odds. In adjusted models, Model 1 included demographic characteristics (age, religion, and marital status); Model 2 added socioeconomic characteristics (poverty, education, and health insurance); and Model 3 added reproductive health characteristics (parity, age at sexual debut, intent for (future) children, number of partners in the past year, and experience of unintended (mistimed or unwanted) pregnancy. “Private” health insurance includes private insurance and Medi-Gap; “Medicaid” includes Medicaid, CHIP, or a state-sponsored health plan; “other or none” includes Medicare, military health care, other government health care, single-service plan only, Indian Health Service only, and not currently covered by health insurance.

Footnotes

We also ran our analyses using the subsample of women who are current contraceptive users (n=6438) and found similar results, but we report on results using the full sample because we were interested in LARC use among the broader population of women of reproductive age.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosher WD, Jones J, National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.) Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. Hyattsville, Md: U.S Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, Petrosky E, Madden T, Eisenberg D, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;95:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilliam ML. Beyond coercion: let us grapple with bias. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:915–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46:171–5. doi: 10.1363/46e1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts DE. Killing the black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. New York: Vintage Books; 1999. 1st Vintage Books edition. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silliman JM, editor. Undivided rights: Women of color organize for reproductive justice. Cambridge, Mass: South End Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kusunoki Y, Barber JS, Ela EJ, Bucek A. Black-white differences in sex and contraceptive use among young women. Demography. 2016;53:1399–428. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0507-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JA, Kramer RD, Ryder KM. Provider bias in long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) promotion and removal: perceptions of young adult women. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1932–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dehlendorf C, Ruskin R, Grumbach K, Vittinghoff E, Bibbins-Domingo K, Schillinger D, et al. Recommendations for intrauterine contraception: a randomized trial of the effects of patients’ race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:319.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Public use data file documentation: 2013-2015. National Survey of Family Growth User’s Guide, HHS; Hyattsville (MD): 2016. pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Finer LB. Changes in use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods among U.S. women, 2009–2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:917–27. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borrero S, Moore CG, Qin L, Schwarz EB, Akers A, Creinin MD, et al. Unintended pregnancy influences racial disparity in tubal sterilization rates. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:122–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grady CD, Dehlendorf C, Cohen ED, Schwarz EB, Borrero S. Racial and ethnic differences in contraceptive use among women who desire no future children, 2006–2010 National Survey of family growth. Contraception. 2015;92:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Hubacher D, Kost K, Finer LB. Characteristics of women in the United States who use long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1349–57. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821c47c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendall C, Afable-Munsuz A, Speizer I, Avery A, Schmidt N, Santelli J. Understanding pregnancy in a population of inner-city women in New Orleans—results of qualitative research. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downing RA, LaVeist TA, Bullock HE. Intersections of ethnicity and social class in provider advice regarding reproductive health. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1803–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker D, Tsui AO. Reproductive health service preferences and perceptions of quality among low-income women: racial, ethnic and language group differences. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40:202–11. doi: 10.1363/4020208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorburn S, Bogart LM. African American women and family planning services: perceptions of discrimination. Women Health. 2005;42:23–39. doi: 10.1300/J013v42n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorburn S, Bogart LM. Conspiracy beliefs about birth control: barriers to pregnancy prevention among African Americans of reproductive age. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:474–87. doi: 10.1177/1090198105276220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson AV, Karasek D, Dehlendorf C, Foster DG. Racial and ethnic differences in women’s preferences for features of contraceptive methods. Contraception. 2016;93:406–11. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.010. n.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JA. Celebration meets caution: LARC’s boons, potential busts, and the benefits of a reproductive justice approach. Contraception. 2014;89:237–41. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mood C. Logistic regression: why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. Eur Sociol Rev. 2010;26:67–82. [Google Scholar]