Abstract

Introduction:

With ageing, the skin gradually loses its youthful appearance and functions like wound healing and scar formation. The pathophysiological theory of Advanced Glycation End products (AGEs) has gained traction during the last decade. This review aims to document the influence of AGEs on the mechanical and physiologic properties of the skin, how they affect dermal wound healing and scar formation in high-AGE populations like elderly patients and diabetics, and potential therapeutic strategies.

Methods:

This systematic literature study involved a structured search in Pubmed and Web of Science with qualitative analysis of 14 articles after a three-staged selection process with the use of in- and exclusion criteria.

Results:

Overall, AGEs cause shortened, thinned, and disorganized collagen fibrils, consequently reducing elasticity and skin/scar thickness with increased contraction and delayed wound closure. Documented therapeutic strategies include dietary AGE restriction, sRAGE decoy receptors, aminoguanidine, RAGE-blocking antibodies, targeted therapy, thymosin β4, anti-oxidant agents and gold nanoparticles, ethyl pyruvate, Gal-3 manipulation and metformin.

Discussion:

With lack of evidence concerning scars, no definitive conclusions can yet be made about the role of AGEs on possible appearance or function of scar tissue. However, all results suggest that scars tend to be more rigid and contractile with persistent redness and reduced tendency towards hypertrophy as AGEs accumulate.

Conclusion:

Abundant evidence supports the pathologic role of AGEs in ageing and dermal wound healing and the effectiveness of possible therapeutic agents. More research is required to conclude its role in scar formation and scar therapy.

Keywords: Advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), skin ageing, photoageing, dermal wound healing, scarring, cicatrix, connective tissue, fibrosis

Lay Summary

Our skin is the body’s first line of defense. It is the barrier that protects us from chemical and biological threats such as viruses, bacteria or corrosive liquids. It is the sensor that allows us to detect physical threats like extreme temperatures, pressure and pain. And when these preventative measures fail, the skin has yet another property: the ability to heal.

Skin changes visibly with age, most notably with the appearance of wrinkles. However, there is more to ageing than meets the eye; invisible alterations cause the decline of various functions of the skin, such as wound healing and scar formation. An array of non-conclusive research has been done in this field. One theory that has gained traction during the last decade is the Advanced Glycation End products (AGEs) theory. The theory states that AGEs play an important role in skin aging, wound healing and the effectiveness of different therapeutic options. Their presence supposedly indicates a diminished ability for wound healing and scar formation.

AGEs are proteins to which sugar molecule is bound. The sugar molecule inhibits the original protein from functioning properly. As skin contains many proteins like collagen, the formation of these AGEs could be a viable explanation for the diminished functioning with ageing. In this review, we investigated whether the accumulation of AGEs affects wound healing and scar formation.

Normal scar formation results in a thin scar. However, it may happen that scarring results in thick, large, painful and itchy scars. We investigated whether people with a high AGE content in their skin, like diabetics and elderly, have difficulties forming aesthetically pleasing scars. Secondly, we investigated which therapies reduce the AGE content and, if so, whether these therapies can improve wound healing and scarring. This literature study involved research in scientific databases with qualitative analysis of 14 articles after a three-staged selection process with the use of set criteria.

We found the different ways in which AGEs affect skin properties and wound healing. Collagen, one of the most important proteins in the skin, is affected by these AGEs. Once a sugar binds to it, the collagen strings becomes thinner and shorter, and the different collagen proteins cross-link with each other in an unstructured way. The result of these alterations is a reduced elasticity, i.e. the skin becomes stiffer. The scar will be thinner and the time for wounds to close is longer. We also found strategies to diminish the AGE content, including dietary AGE restriction and Metformin, a drug used in diabetes.

We can conclude that there is proof of AGEs playing an important role in skin ageing, wound healing and the effectiveness of different therapeutic options. However, more research is required to conclude the exact role of AGEs in scar formation and scar therapy.

Introduction

With ageing, the skin is subjected to stresses that alter its properties, gradually diminishing its function and youthful appearance.1 A recent pathophysiological theory that has gained traction during the last decade is the process of advanced glycation end products (AGE) formation. During this process, organic proteins like collagen undergo irreversible glycation, influenced by oxidative stress.2 As scar formation is characterised by excessive collagen deposition, factors that negatively influence the structure and function of collagen may cause impaired scarring. This paper reviews the influence of AGEs on the mechanical and physiological properties of the skin, more specifically how they affect scar formation in elderly patients and what potential therapeutic strategies are described in the literature.

Background

Skin

Function

The skin performs multiple functions.3 Its primary purpose is to act as a border between the body and its surroundings, protecting the human body against mechanical, thermal, microbial and chemo-radial threats. However, this makes the skin itself vulnerable to both external and internal stresses.4,5 Furthermore, it regulates temperature through sweat production, piloerection and changing the superficial vascular flow. Vitamin D synthesis also takes place partially in the skin. The skin’s ability to sense cold, heat, pain and touch serve as a warning against severe trauma, burns or hypothermia. Another frequently overlooked function is its aesthetic function; the appearance of the skin affects the way a person is perceived and treated by other members of society.6 This aesthetic appearance can be degraded by alterations in the skin characteristics, which are affected by the ageing processes, scarring, smoking, ultraviolet (UV) exposure, hygiene and diet. A great deal of dermatology research presently aims to find ways to counteract these changes in appearance, either by prevention or restoration.

Structure

The skin consists of three main layers: the epidermis, the dermis and the subcutaneous fat.7 These layers all play a significant role in the function of the skin. The epidermal layer is the outer covering, mainly composed of keratinocytes arranged in four layers: stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum and stratum basale. It contains various immune cells and keratinocyte progenitor cells. The colour of skin is determined by melanocytes situated at the base of this layer, but can also be altered as a result of inflammatory reactions after injury. The dermis, on the other hand, is the supportive connective tissue. It has sweat glands for thermoregulation and nerve endings for sensation. It also contains hair follicles and vessels. Seventy percent of the dermis is made up of collagen fibres, produced by fibroblasts. These cells also produce elastin and other connective tissue and glycosaminoglycans. Other cells in the dermis include mast cells, macrophages, dendritic cells and lymphocytes. The deepest layer, the subcutaneous layer, stores fat and helps to insulate the body.

Wound healing

When tissue gets injured, a regeneration process begins. Healthy skin has an excellent regeneration capability because it is well vascularised and contains a pool of epidermal stem cells able to proliferate and regenerate.8 However, some factors may interfere with the normal healing process, which will be discussed later on. Besides stem cells, other actors like fibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, extracellular matrix, cytokines and growth factors, are necessary to restore the damage. In general, the wound healing process is arbitrarily divided into four phases which overlap in time and space: haemostasis/coagulation, inflammation, proliferation/repair and maturation.4

Following injury, small blood vessels constrict to ensure haemostasis and then vasodilate to promote thrombocyte invasion and coagulation.9 The clotting cascade forms a firm fibrin clot, which, in addition, is used as a matrix for invading cells and as a reservoir for cytokines and growth factors.10 In the inflammatory phase, neutrophils activated by the coagulation cascade are attracted to the site by growth factors and cytokines such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and interleukin (IL)8. These polymorphonuclears clear the debris and ingest microorganisms, which are later phagocytised by macrophages. The macrophages additionally secrete mediators perpetuating inflammation and activating the proliferative phase.11 Proliferation of epithelial cells covers the wound, thus acting as a barrier against foreign material. Neo-vascularisation and extracellular matrix secretion by fibroblasts creates granulation tissue beneath the lesion.12 Fibroblasts then differentiate into myofibroblasts causing contraction of the wound margins. The maturation phase can last up to two years after initial injury6 and is characterised by further cell apoptosis, diminished neovascularisation and replacement of collagen type III to stronger collagen type I.

Risk factors for impaired wound healing

Individual risk factors for poor wound healing can be distinguished by the way they interfere with one or more phases of normal wound healing. The most important ones are peripheral artery disease, diabetes, chronic venous insufficiency, ageing, immunosuppressive therapy, sickle cell disease, malnutrition, infection, immobilisation, smoking and prior radiotherapy. The phenomenon by which ageing enhances the risk of poor or slow wound healing is a consequence of poorly understood mechanisms that lead to decreased supply of cutaneous nerves and blood vessels, thinning of the skin and diminished ability to produce new collagen.13

Scarring

A scar in the skin may be defined as a macroscopic disturbance of the normal structure and function of the skin architecture, resulting from a healed wound.14 Scars can be divided into different groups according to their appearance. Various tools are available to evaluate the characteristics of these scars.15 Raised skin scars are described as hypertrophic or keloid, with the main difference being the boundaries of the scar, as keloids exceed the boundaries of the initial lesion and hypertrophic scars do not.16 The pathophysiological mechanisms of keloids and hypertrophic scars are not completely known. Different cytokines have been implicated, including IL6, IL8 and IL10, as well as various growth factors including transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and PDGF.17 Several scar therapies exist including conventional (occlusion, compression, steroid injection), surgical (excision, cryosurgery) and adjuvant (radiotherapy) strategies. The use of different chemotherapeutic agents has been studied.16

Ageing

With ageing, the skin undergoes various changes, the most conspicuous being the appearance of wrinkles. The causes of these changes can be classified as exogenous or endogenous factors, which can be divided by UV-protected versus UV-exposed sites.18 Exogenously aged skin has a thickened epidermis and aggregation of abnormal elastic fibres in the dermis.17 Endogenously aged skin becomes generally thinner, atrophic with diminished elasticity, and reflects the ageing process in internal organs.19,20 The causes of cellular senescence include decreased proliferative capacity, a decrease in cellular DNA repair capacity leading to chromosomal abnormalities, loss of telomeres, oxidative stress and gene mutations.21 Besides visible structural changes, functionality also declines. There is reduced strength and flexibility, impaired barrier functionality, altered immunity and vascular changes. The skin’s protective function is thereby weakened. Foreign mechanical stresses such as chemicals, soaps and antigens can, therefore, penetrate and injure the skin more easily, causing adverse reactions, infection or scarring. As protection against oxidative stressors is reduced, UV light becomes more damaging. As neural and vascular supply declines, sensation, thermoregulation and perspiration are all blunted, further reducing the skin quality.5

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs)

A recent pathophysiological theory that has gained traction during last decades is the process that results in the formation of AGEs.

Formation

AGEs are a very heterogeneous group of substances.22 The term encompasses all molecules like proteins, lipids and nucleic acids that degenerate because of binding sugar molecules. The formation of AGEs is a multistep process and three principal components are essential: sugars, oxidative stress and sufficient time. First, a process called glycation, or Maillard reaction, occurs, in which a reduced sugar anchors to a free amino acid, hence forming a Schiff base.23 This is a non-stable and reversible intermediate product and is formed over the period of a few hours, and is the same process responsible for the browning of food in thermal processes.24,25 During the following days, a Schiff base can transform into an Amadori product, which is stable but again still reversible intermediate. Both can eventually become irreversible AGEs by undergoing oxygenation and dehydration reactions. This phase requires more time and, therefore, only long-living glycated proteins like collagen, albumin, LDL and haemoglobin will be susceptible to this conversion. Proteins that are excreted or broken down too swiftly are not prone to this conversion. This last oxidative step is obligatory in the formation of advanced glycation end products.26

Sources

Everybody is subjected to AGE formation.27 Accumulation of AGEs is reported as young as the age of 20 years and appears to increase steadily subsequently.28 The cause of AGE formation is twofold, being either exogenous ingestion or endogenous production. The accumulation can further be worsened by a diminished excretion capacity in the case of renal impairment, being part of a negative feedback loop as explained later. It has been observed that some foods contain more AGEs than others, with the single most important factor being the preparation method of food.29 The endogenous production, on the other hand, can be increased by diabetes, smoking and consuming or using things that raise the amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS).30 Among these risk factors, diabetes is possibly the most significant and most well documented, caused by hyperglycaemia.

Elimination of AGEs occurs by renal clearance. Unfortunately, the kidneys are also target organs of AGEs, causing structural changes of progressive nephropathies including glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy.31 Together, this generates a positive feedback loop in which AGEs progressively accumulate and further impair the renal function.32

Targets of AGEs

AGEs can affect the function of organs through multiple pathways.33,34 First, if a reversible Amadori product or Schiff base reacts irreversibly with an amino acid of a protein, a protein-adduct or protein-crosslink is formed, leading to (partial) loss of normal structure and function. Second, binding to an AGE-receptor (RAGE) leads to increased oxidative stress and inflammation by interrupting normal intracellular signalling and processes. The soluble isoform of RAGE (sRAGE), present in human plasma, is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form.35,36 It binds circulating AGEs and so is regarded as a potential decoy for RAGE signalling pathways.37 On the other hand, it can have pro-inflammatory effects through interaction with Mac-1.38 Studies recently showed that sRAGE could be used as a marker for AGE-mediated diseases, with a negative correlation between serum sRAGE and AGE-induces pathologies, making its use a possible therapeutic strategy.39 The third mechanism by which AGEs affect different organs is through binding lipoproteins. It may lead to the formation of foam cells, an important risk factor in the development of atherosclerosis, which can lead to myocardial infarction and stroke.40

AGEs and skin

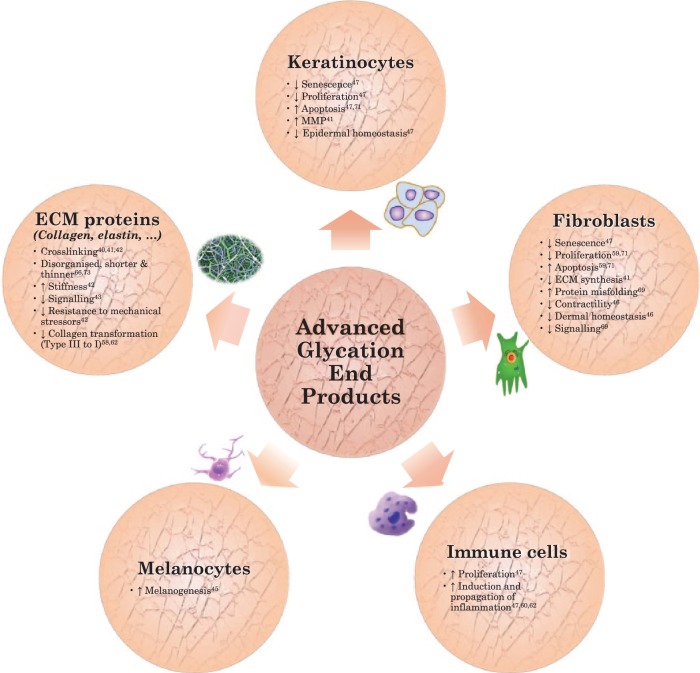

The consequences of AGE accumulation on the skin are a subject of interest in recent literature aiming at finding causes for diminished appearance and decreased function of the skin with ageing. As in all organs, long-lived proteins are particularly prone to oxygenation. In the skin, this primarily affects dermal extracellular matrix proteins including collagen, fibronectin and elastin.41,42 Different skin collagen fibrils can, if glycated, conjointly form crosslinks, making skin more stiff and diminishing its ability to resist mechanical stressors.43 When membrane contact sites become affected, communication with other cells and proteins will be impaired.44 Glycated skin collagen also seems to be less susceptible to MMP activity. This interferes with the normal removal of old collagen fibrils as well as the formation of new ones and can therefore lead to decreased transformation of collagen-III into collagen-I fibres.

Besides Extracellular Matrix (ECM) proteins, skin cells are also subjected to negative effects of AGEs as they contain RAGEs on their surfaces, and their intracellular proteins can also be affected.45 Receptors for AGEs have already been detected in vivo on surfaces of keratinocytes, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and immune cells by immunohistochemistry. The existence of RAGE on melanocytes has been demonstrated by western blot and immunofluorescence, and binding of AGEs to these RAGEs promotes melanogenesis.46 RAGE activation causes fibroblasts to lose contractility as well as turnover ability.47 Dermal and epidermal homeostasis is disturbed as keratinocytes gradually lose their proliferation capacity and become more susceptible to apoptosis.48 On the other hand, immune cells proliferate and induce and propagate inflammation. It is notable that sun exposure seems to increase RAGE density.49

AGEs and wound healing

Fibroblasts play a leading role in wound healing, particularly in the skin. To participate in wound repair, they must migrate into the wound, proliferate and form new extracellular matrix.11 Because normal healing needs a sufficient amount of cells to repair the injuries, apoptosis induced by different mechanisms like AGE/RAGE binding could impair adequate healing. Because of this, poor wound repair in the elderly and diabetics could be explained as a result of the formation of AGEs.50,51

Possible therapeutic strategies

As AGEs play an important role in negatively altering the physiology and morphology of skin, considerable research has focused on ways to counteract these changes. Substances inhibiting the formation of AGEs can be used preventively, including aminoguanidine,52–54 pyridoxine (vitamin B6),55 isopropylidenehydrazono-4-oxo-thiazolidin-5-ylacetanilide (OPB-9195).56,57 Caloric restriction has also been proven to diminish AGE accumulation and increase the lifespan of rats.58

An alternative is to target previously formed AGEs by using substances that break them down or neutralise them. Different neutralisers have been identified, among which are vitamins C and E, various herbs and spices (cinnamon, marjoram, tarragon, ginger, rosemary),59 blueberry extract,60 green tea,61 natural flavonoids,62 zinc, manganese, alpha-lipoic acid and selenium yeast.63 Topical administration of dimethyl-3-phenayl- thiazolium chloride (ALT-711 or alagebrium), a potent crosslink breaker, was effective in improving the skin hydration of aged rats.64

Targeted therapy aims at downregulating genes coding for RAGE or at inhibiting signalling pathways. In this respect, Plantamajosi has proven to be protective.65

Finally, besides being a marker for AGE-induced disease, the soluble AGE receptor, acts as a decoy for RAGE by competitive inhibition. Protective effects already have been proven in diabetic and inflammation models.66

This review aims to document the influence of AGEs on the mechanical and physiologic properties of the skin, how they affect dermal wound healing and scar formation in high-AGE populations like elderly patients and diabetics, and potential therapeutic strategies.

Methods

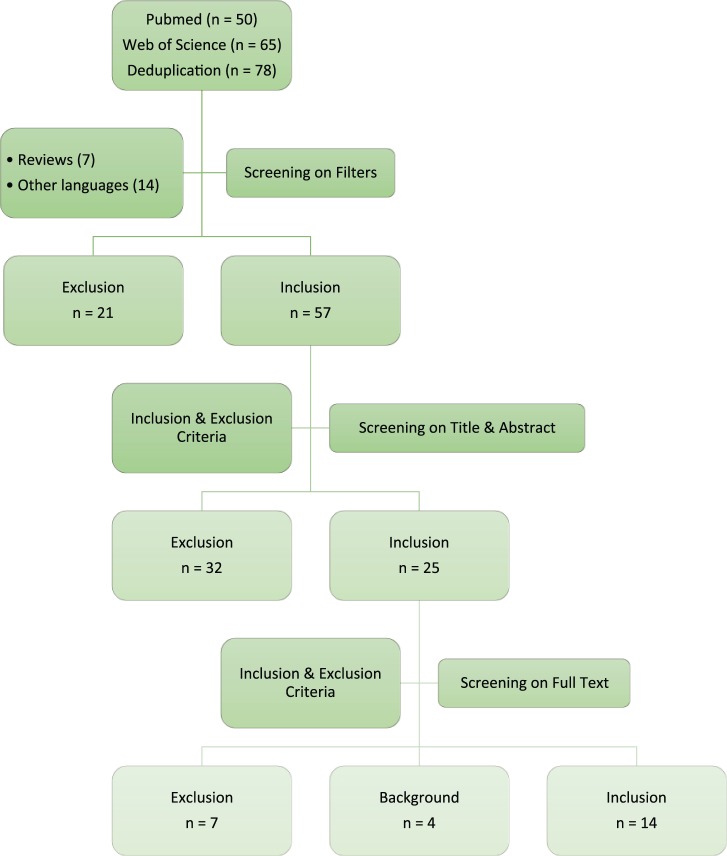

This systematic review consists of three phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological flowchart.

In phase one, we searched electronic databases PubMed and Web of Science for AGEs AND skin AND scarring OR dermal wound healing. See box 1 and 2 for the full search terms for the respective databases.

Box 1.

Search term PubMed.

| (‘Glycosylation End Products, Advanced’[MESH] OR ‘Advanced Glycation End Products’ OR ‘Glycation End Products, Advanced’ OR ‘Advanced Glycosylation End Products’) AND (‘Skin’ OR ‘Skin’[MESH] OR ‘Dermal’ OR ‘Skin Ageing’[MESH] OR ‘Skin Ageing’ OR ‘Photoageing’) AND (‘Cicatrix’[MESH] OR ‘Scars’ OR ‘Scarring’ OR ‘Wound Healing’[MESH] OR ‘Wound Healing’ OR ‘Fibrosis’[MESH] OR ‘Connective Tissue’[MESH]) |

Results: 50.

Box 2.

Search term Web of Science.

| (‘Glycosylation End Products, Advanced’ OR ‘Advanced Glycation End Products’ OR ‘Glycation End Products, Advanced’ OR ‘Advanced Glycosylation End Products’) AND (‘Skin’ OR ‘Dermal’ OR ‘Skin Ageing’ OR ‘Photoageing’) AND (‘Cicatrix’ OR ‘Scars’ OR ‘Scarring’ OR ‘Wound Healing’ OR ‘Fibrosis’ OR ‘Connective Tissue’) |

Results: 65.

Phase two consisted of data collection and data extraction. Data collection was executed on 1 July 2016, resulting in 50 articles on PubMed and 65 articles on Web of Science. After deduplication, exclusion of review articles and articles in languages other than English, 57 articles remained. A second screening selection was based on analysis of relevant titles and abstracts. These screenings and all of the following analyses were done by two independent readers, to improve reliability. Articles that did not involve all three components of the search term – AGEs, skin and scarring or dermal wound healing – were excluded. This resulted in 25 remaining articles. Finally, a data collection by analysing the full text of the articles regarding the main research question retained 14 articles for qualitative analysis. Subsequently, data were extracted in function of the relevant outcomes. The primary outcome was the relation between AGEs and the characteristics of scar tissue. These characteristics are objectified by qualitative markers, namely: scar size, contractility, pigmentation, signs of inflammation, pruritus and pain. The secondary outcome was the relation between AGEs and wound healing and skin characteristics and potential therapeutic strategies that specifically target AGEs-related pathways in the skin.

The third phase consisted of reporting the results and the drawing of relevant conclusions in function of the research question.

Results

Results of the articles retained after data collection are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main findings of relevant articles.

| Year | Authors | Sample size | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Peppa, M | 100 | • High AGE-containing diets increased skin AGE deposits, which decreased epithelialisation, angiogenesis, inflammation, granulation tissue deposition and collagen organisation up to 21 days, increased contraction and delayed wound closure |

| 2004 | Maggitti, KW | 15 | • Interaction of AGEs with the receptor for AGEs (RAGE) resulted

in an exaggerated inflammatory response and compromised collagen

production, which lead to impaired wound healing • sRAGE treated wounds show increased granulation tissue area and microvascular density |

| 2005 | Yavus, D | 16 | • Aminoguanidine improves wound healing, restores growth factor TGFbeta1 expression and preserves collagen ultrastructure, whereas it has no prominent effect on NO levels within wound tissue in diabetic rats |

| 2008 | Niu, YW | 18 | • Glycosylated matrix induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of cultured dermal fibroblasts, whereas application of RAGE-blocking antibodies redressed these changes |

| 2009 | Loughlin, DT | * | • Fibroblast/matrix interactions are altered as AGEs accumulate

and affect focal adhesion formation • 3DG (3-deoxyglucosone) may be a factor mediating chronic wounds observed in patients with diabetes and in the elderly by altering the signalling within the fibroblast and inducing the missfolding of proteins |

| 2011 | Yuanchang, Z | 50 | • The plasma level of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and its mRNA in white blood cells were found to be significantly higher in the wounded mice fed with high dietary AGEs than others |

| 2012 | Chen, SA | 135 | • The mixture of AuNP+EGCG+ALA (AuEA) significantly reduced the AGE-induced RAGE protein expression in fibroblasts (Hs68) |

| 2012 | Niu, YW | 33 | • Accumulation of AGEs in diabetic skin tissue induces an oxidative damage of fibroblasts and acts as an important contributor to the thinner diabetic abdominal dermis, demonstrated histologically by reduced thickness with shortened, thinned and disorganised collagen fibrils with focal chronic inflammatory cell infiltration |

| 2012 | Zhang, Q | 14 | • In vivo treatment with ethyl pyruvate (EP) significantly

decreased wound HMGB1 levels (P <0.05),

which was paralleled by increased wound breaking strength

(P <0.05) and wound collagen content

(P <0.05) • In vitro treatment with HMGB1 (100 ng/mL) had no effect on fibroblast proliferation but significantly reduced collagen synthesis (P <0.05). This effect was abrogated by co-treatment with anti-RAGE antibody • Fibroblasts treated with AGE had lower collagen synthesis (P <0.01), which was restored by anti-RAGE antibody treatment |

| 2014 | Pepe, D | 16 | • Gal-3, a matricellular protein upregulated in excisional skin repair and modulator of the inflammatory phase of repair and recently shown to be a receptor for AGEs (RAGE), decreases the accumulation of AGEs in wound healing |

| 2014 | Kim, S | 70 | • Tβ4r downregulated the receptor of AGE (RAGE) during the wound

healing period • After treatment, Tβ4 improved wound healing markers such as wound closure, granulation and vascularisation (Tβ4 = Thymosin β4) |

| 2016 | Tian, M | 36 | • Deposition of AGE in diabetic rat skin activates the neutrophils even before injury. After injury, the normal physiological inflammatory reaction failed to occur adequately because exposure to AGE inhibited the viability of PMNs, promoted RAGE production and cell apoptosis, and prevented the migration of PMNs |

| 2016 | Das, A | 10 | • Hyperglycaemia and exposure to advanced glycated end products

inactivated MFG-E8, impairing efferocytosis accompanied with

persistent inflammation and slow wound closure • Topical recombinant MFG-E8 induced resolution of wound inflammation, improvements in angiogenesis and acceleration of closure |

These studies represent histological studies with unspecified amounts of certain media.

Skin and wound effects

Niu66 immunohistochemically demonstrated a higher accumulation of AGEs in the skin of diabetic mice in comparison to healthy control mice. Examination of haematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of control and diabetic groups revealed that the thicknesses of the dermal layers in the diabetic abdominal skin were significantly decreased. The epithelium of diabetic skin consisted of a disordered or deficient multilayer with fewer spinous cells. The diabetic collagen fibrils were shortened, thinned and disorganised, with focal chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, compared with controls of the same age. The diabetic collagen was not tightly packed and was not as well aligned as in controls.

Tian67 demonstrated that AGE accumulation in diabetic rat skin activated neutrophils before injury, reducing their viability and function. Moreover, after injury, neutrophil migration and accumulation at the burn site were diminished and a dense inflammatory band failed to form. AGE deposition caused enhanced RAGE expression, delayed expression of inflammatory cytokines and accelerated cell apoptosis.

Milk fat globule epidermal growth-factor 8 (MFG-E8), a bridging molecule between macrophages and apoptotic cells, helps to resolve inflammation, supports angiogenesis and accelerates wound closure. Das68 showed that it is inactivated in diabetic db/db mice by both hyperglycaemia and exposure to AGEs. Clinically this resulted in persistent inflammation and delayed wound healing. Furthermore, topical application of recombinant MFG-E8 induced resolution of wound inflammation improved angiogenesis and accelerated wound closure.

Wound repair is dependent on fibroblast migration, proliferation and expression of extracellular matrix proteins. Loughlin studied the effect of 3-deoxyglucosone (3DG)-collagen on human dermal fibroblast migration and adhesion.69 Results showed an alteration of fibroblast/matrix interactions and affected focal adhesion formation as AGEs accumulate. 3DG was found to be a factor mediating chronic wounds observed in patients with diabetes and the elderly by altering the signaling within the fibroblast and inducing the misfolding of proteins.

Diet

AGEs in foods

Yuanchang70 extensively discussed different foods in relation to AGEs, to further analyse their effects on wound healing. For instance, AGEs were not detected in any fruits and vegetables, including apple, banana, peach, orange, soybean, cabbage, lettuces and bok choy. However, among fast foods, fried chicken was found to have the highest content of AGEs, followed by French fries, hamburger, fish steak, hot dog and chicken steak. AGEs appeared to be higher in oil-fried food and lower in steamed or stewed food. Different cooking methods seemed to have different effects on formation of dietary AGEs. Steaming of the food produces fewer AGEs compared to the use of a microwave or frying. Steam appeared to be the cooking that produced the least dietary AGEs. In addition, more AGEs are produced in pork when using the microwave, while frying produces more AGEs in fish and eggs.

In diabetic mice, a high AGE diet increased protein-linked tissue deposition of AGEs, when compared with low AGE-fed mice, whereas no increases in AGE accumulation were observed despite prolonged diabetes. Comparably, high AGE-fed mice had more collagen-associated AGE accumulation compared with those on a low AGE diet.71

Effects of dietary glycotoxins on wound healing

Peppa61 showed that the amount of orally ingested glycotoxins could alter the time and the quality of wound healing in diabetic mice significantly. Increased dietary AGE intake delayed the wound closure time and interfered with angiogenesis and granulation tissue maturation, which were in contrast to those associated with a low AGE-fed diet. Oral administration of high AGE-containing foods causes severe toxicity responses.60 In wounded mice, this resulted in significantly higher mortality. However, high dietary AGEs did not cause observable toxic responses in non-wounded mice, indicating that dietary AGEs might not have adverse effects on healthy animals. This might be mainly due to the sustained non-subsiding inflammatory responses that were significantly potentiated by AGEs, causing severe systemic inflammation in wounded mice but not in non-wounded mice. Starting from day seven after wounding, diabetic, high AGE-fed mice displayed delayed closure compared with high AGE-fed mice with lower cellularity at the wound–dermis interface, consistent with a lower inflammatory response at the wound site. At day 14, wounds displayed sustained inflammation, fewer blood vessels and a lower degree of re-epithelialisation. In the high AGE-fed mouse wounds, the intensity and patterns of deposited collagen fibres were consistent with finer, less organised collagen fibres throughout. These wounds did not close for up to 24 days.

HMGB1 or high-mobility group box 1 protein, also known as amphotericin, has been identified as a ‘late’ inflammatory mediator. Extracellular HMGB1 can bind to different cell surface receptors, including the RAGE. Yuanchang60 showed that HMGB1 has an inhibitory effect on incisional wound healing. Wounded mice fed with higher dietary AGEs had significantly higher expression levels of HMGB1 mRNA in WBC and a significantly higher HMGB1 level in blood, suggesting a strong systemic inflammatory response in the body. By activating RAGE, HMGB1 impaired fibroblast-mediated collagen synthesis with reduced tensile strength.

Therapeutic strategies for wound healing

The results of investigated therapeutic strategies discussed below cover anti-AGE therapies for wound healing only, in contrast to the therapeutic options mentioned in the background section.

sRAGE

Using genetically diabetic C57BLks-db/db mice, Wear-Maggitti72 applied sRAGE, a soluble form of RAGE, topically to standardised full-thickness wounds to improve diabetic wound healing. They measured various parameters of wound healing such as neovascularisation, re-epithelialisation, collagen formation and granulation tissue area. They noticed a statistically significant increase in neovascularisation in the wounds treated with topical sRAGE when compared with the control group and also a significant increase in the quantity of granulation tissue formed with sRAGE treatment. Furthermore, there was a trend toward a smaller residual epithelial gap with the sRAGE-treated group compared with the control group, albeit not significant. sRAGE may be a powerful treatment of accelerating diabetic ulcer healing.

RAGE-blocking antibodies

Niu73 demonstrated that in diabetic skin, collagen fibrils were shortened, thinned and disorganised compared with controls of the same age and the number of RAGE-positive cells was increased in the dermal layer. The quantity of viable fibroblasts growing on the glycosylated matrix on the first, second and third days was significantly reduced when compared with fibroblasts grown on the control matrix. Glycosylated matrix induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of cultured dermal fibroblasts, whereas application of RAGE-blocking antibodies reversed these changes.

Aminoguanidine

Aminoguanidine, which is an advanced glycation and nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor, was evaluated in the study of Yavus74 to investigate its effect on extracellular matrix protein expression, collagen configuration and nitrite/nitrate levels in wounds of diabetic rats. Aminoguanidine improves wound healing, restores growth factor TGF-β1 expression and preserves collagen ultrastructure, whereas it has no prominent effect on NO levels within wound tissue in diabetic rats.

Thymosin β4 (Tβ4)

Kim75 evaluated the improvement of healing of burn wounds by Thymosin β4 in relation to AGEs. Intradermal treatment with Tβ4 downregulated the expression of RAGE during the wound healing period and improved wound healing markers such as wound closure, granulation and vascularisation.

Gold nanoparticles

Chen76 tested the relationship between RAGE expression and topical application of anti-oxidant agents with gold nanoparticles (AuNP) in cutaneous diabetic wounds. The mixture of AuNP, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and a-lipoic acid (ALA) significantly reduced the AGE-induced RAGE protein expression in fibroblasts (Hs68). This combination (AuEA) significantly accelerated diabetic cutaneous wound healing through angiogenesis regulation and anti-inflammatory effects. The blocking of RAGE by anti-oxidant agents and nanoparticles may restore effective wound healing in diabetic ulcer.

Galactin-3 (Gal-3)

Matricellular protein galectin-3 has recently been shown by Pepe77 to be a receptor for AGEs. Where Gal-3 immunoreactivity is reduced in the epidermis and vasculature, there is a concomitant increase in the level of AGE staining. The inverse correlation between Gal-3 and AGEs prevalence suggests that Gal-3 may protect against accumulation of AGEs in wound healing, by binding and clearing these molecules.

Ethyl pyruvate

Zhang78 studied ethyl pyruvate (EP), a potent inhibitor of HMGB1 release, in rats who underwent full-thickness incisional wounding. In vivo treatment with EP significantly decreased wound HMGB1 levels, which was paralleled by increased wound breaking strength and wound collagen content.

Discussion

An increase of dietary AGE intake delays closure time and interferes with angiogenesis and granulation tissue maturation in diabetic wounds.61 The effects of this intervention are directly related to circulating and tissue-retained AGE accumulation, confirming that systemic effects of toxic derivatives extend to skin tissue. In diabetic patients and animal models, both AGEs and tumour necrosis factor are at higher levels, causing high inflammatory responses and apoptosis of matrix-producing cells.79 In skin containing higher amounts of AGEs, collagen organisation is disrupted, causing thinning of the skin.56 The results suggest that despite an intact skin condition, unusual histological structures (thinner dermis and disorganised collagen fibres), elevated MPO activity, increased MDA content and cutaneous environmental alteration (AGE accumulation) had already been in existence in diabetic patients.56 Changing the amount of orally ingested glycotoxins can alter the time and the quality of wound healing in diabetic animals significantly. In vitro observation indicated the possible relationship between diabetic skin disorders and the accumulation of AGEs in diabetic skin.56 Having identified the compromising cutaneous properties of diabetic skin at baseline, these underlying disorders may play an important role in the increased susceptibility to injury, and atypical means of the diabetic wound healing process including scar formation.

Improving skin properties at baseline could lead to a reduction in morbidity and economic costs related to diabetes, though additional investigations into diabetic skin properties and the role played by skin properties in diabetic wound healing are warranted. The harmful effects associated with a high AGE diet were not limited to wound healing; similar effects were demonstrated on renal function, based on an albumin/creatinine ratio, consistent with previous studies.61 Based on these data, accelerated renal dysfunction and delayed wound healing may be interrelated processes in diabetes, the connecting link being an AGE-dependent inflammatory response. Moreover, diet-originating AGEs are important determinants of the total AGE pool and consequently of systemic AGE toxicity.61 Dietary AGE lowering may, therefore, prove to be an effective approach for both restoring physiological wound healing and therefore improve outcome for scarring as well as stabilising renal function, as already suggested for other diabetic complications.

The effects of AGEs on various dermal structures is schematically illustrated in Figure 2. An extended search for ‘wound healing and AGEs’ was necessary besides the initially aimed ‘scarring and AGEs’ to include sufficient articles for qualitative research. A lack of evidence about the effect of AGEs on scar formation made this step mandatory. As a consequence, most articles covered the implications of AGEs on skin-ageing or wound healing in diabetic patients. Therefore, no absolute conclusions can be made about the role of AGEs on eventual appearance/function of scar tissue. However, the eventual appearance of scar tissue might be predicted by extrapolating known effects of AGEs on the skin and wound healing. All results suggest that scars tend to be more rigid and contractile with persistent redness and reduced tendency towards hypertrophy as AGEs accumulate. Because AGEs are present in higher amounts in the skin of both diabetics and elderly, similar effects as seen in diabetics would presumably be observed in seniors. Unfortunately, these two populations have somewhat different wound healing propensities. One somewhat paradoxical advantage in elderly patients is the ability to visually heal better than younger patients following cutaneous surgery.80 In older patients, the incision lines are less red, the scarring is less hypertrophic and ‘normalisation’ of appearance occurs more rapidly. Nevertheless, negative age-dependent changes in the physical characteristics of the skin and the wound-healing pathway may affect the vitality and structural integrity of the postoperative result.70 These contradictory findings undermine the deduction of wound healing trends to scar formation and make investigating the direct effects of AGEs on scar formation and eventual appearance obligatory

Figure 2.

Dermal effects of Advanced Glycation End Products.

Further investigations

On the subject of the relation between AGEs and scars, we suggest various future studies.

First, it is important to demonstrate a correlation between the amount of AGEs in the skin and scar characteristics. Different established scar characteristics include pliability, firmness, colour, thickness, perfusion, size, contour, etc. Several valid scar scoring systems exist, yet a universal scoring system is not available. However, this would be useful to characterise better, comprehend, compare and treat pathological scarring.14 Different methods to measure the amount of AGE accumulation in skin are available. Initially, measuring was done by western blot with polyclonal antibodies or by autofluorescence on skin biopsies.81 Therefore, the use of these measurements was restricted. Recently, though, a non-invasive AGE-reader was introduced, which can measure the skin content of AGEs in vivo. It uses the autofluorescent characteristics of advanced glycation end products.82,83 By combining the assessment of a valid scar assessment with determining the amount of AGEs in the skin, a correlation could be established.

In a second stage, the effects of anti-AGE strategies on scar characteristics can be investigated. Known therapeutic strategies like dieting and the use of anti-oxidative substances (e.g. topical antioxidant cream) could be tested. Furthermore, oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) like metformin could be assessed as metformin improves basal blood glycaemia. Apart from the effects on the glycaemic profile, metformin appears to improve scar formation by targeting skin fibroblasts.84 It has an inhibitory effect on AGEs-induced apoptosis in human dermal fibroblasts by regulating the expressions of caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2.85

Conclusion

Accumulation of AGEs in the skin has extensively been demonstrated in both the elderly and diabetics. Abundant evidence supports the pathological role of AGEs in ageing and wound healing and the effectiveness of possible therapeutic agents. However, no conclusions can yet be made concerning eventual scar appearance because of lack of evidence and conflicting patterns of wound healing in diabetic versus elderly patients, both of which have high levels of AGEs. Therefore, more research is required to conclude the exact role of AGE accumulation in scar formation and scar therapy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Robert Charles Stabler for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Viña J, Borrás C, Miquel J. Theories of ageing. IUBMB Life 2007; 59: 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Paul RG, Bailey AJ. Glycation of collagen: the basis of its central role in the late complications of ageing and diabetes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1996; 28: 1297–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tortora GJ, Grabowski SR. Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. New York, NY: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adam J, Singer M, Richard AF, et al. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fore J. A review of skin and the effects of ageing on skin structure and function. Ostomy Wound Manage 2006; 52: 24–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alam M, Dover JS. On beauty: evolution, psychosocial considerations, and surgical enhancement. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 795–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gawkrodger D, Ardern-Jones M. Dermatology, an illustrated colour text. 5th edn. Elsevier, London: Churchill Livingstone, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cerqueira MT, Pirraco RP, Marques AP. Stem cells in skin wound healing: are we there yet? Advances in Wound Care 2016; 5: 164–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robson MC, Steed DL, Franz MG. Wound healing: biologic features and approaches to maximize healing trajectories. Curr Probl Surg 2001; 38: 72–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin P. Wound healing – aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 1997; 276: 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008; 453: 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rubin E, Farber JL. Pathology. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reddy M. Skin and wound care: important considerations in the older adult. Adv Skin Wound Care 2008; 21: 424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferguson MWJ, Whitby DJ, Shah M, et al. Scar formation: the spectral nature of fetal and adult wound repair. Plastic Reconstructive Surg 1996; 97: 854–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty 2010; 10: 43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGrouther DA. Hypertrophic or keloid scars? Eye 1994; 8: 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berman B, Maderal A, Raphael B. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Dermatol Surg 2016. DOI: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ganceviciene R, Liakou I, Theodoridis A, et al. Skin anti-ageing strategies. Dermatoendocrinol 2012; 4: 308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Engelke M, Jensen JM, Ekanayake-Mudiyanselages S, et al. Effects of xerosis and ageing on epidermal proliferation and differentiation. Brit J Derm 1997; 137: 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zouboulis CC, Makrantonaki E. Clinical aspects and molecular diagnostics of skin ageing. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29: 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC, William J. Characteristics and pathomechanisms of endogenously aged skin. Dermatology 2007; 214: 352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peppa M, Raptis SA. Advanced glycation end products and cardiovascular disease. Curr Diabetes Rev 2008; 4: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maillard LC. Formation of melanoidins in a methodical way. Compt Rend 1912; 154: 66. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu JT. Advanced glycosylation end products: a new disease marker for diabetes and ageing. J Clin Lab Anal 1993; 7: 252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hodge JE. Dehydrated foods, chemistry of browning reactions in model systems. J Agric Food Chem 1953; 1: 92843. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmed N. Advanced glycation endproducts–role in pathology of diabetic complications. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005; 67: 3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hipkiss AR. Accumulation of altered proteins and ageing: causes and effects. Exp Gerontol 2006; 41: 464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dunn JA, McCance DR, Thorpe SR, et al. Age-dependent accumulation of N epsilon- (carboxymethyl)lysine and N epsilon-(carboxymethyl) hydroxylysine in human skin collagen. Biochemistry 1991; 30: 1205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, et al. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J Am Diet Assoc 2010; 110: 911–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nicholl ID, Stitt AW, Moore JE, et al. Increased levels of advanced glycation endproducts in the lenses and blood vessels of cigarette smokers. Mol Med 1998; 4: 594–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bohlender JM, Franke S, Stein G, et al. Advanced glycation end products and the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2005; 289: 645–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ejtahed HS, Angoorani P, Asghari G, et al. Dietary advanced glycation end products and risk of chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2016; 26: 308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vlassara H, Palace MR. Diabetes and advanced glycation endproducts. J Intern Med 2002; 251: 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vlassara H. The AGE-receptor in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Diabetes Metab Res 2001; 17: 436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Devangelio E, Santilli F, Formoso G. Soluble RAGE in type 2 diabetes: Association with oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2007; 43: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Raucci A, Cugusi S, Antonelli A, et al. A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). FASEB J 2008; 22: 3716–3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ramasamy R, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. RAGE: therapeutic target and biomarker of the inflammatory response- -the evidence mounts. J Leukoc Biol 2009; 86: 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pullerits R, Brisslert M, Jonsson I-M, et al. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products triggers a proinflammatory cytokine cascade via beta2 integrin Mac-1. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 3898–3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Basta G. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and atherosclerosis: From basic mechanisms to clinical implications. Atherosclerosis 2008; 196: 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meerwaldt R, Links T, Zeebregts C, et al. The clinical relevance of assessing advanced glycation endproducts accumulation in diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2008; 7: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bucala R, Cerami A. Advanced glycosylation: chemistry, biology, and implications for diabetes and ageing. Advances in Pharmacology 1992; 23: 1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pageon H, Zucchi H, Rousset F, et al. Skin ageing by glycation: lessons from the reconstructed skin model. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014; 52: 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Verzijl N, DeGroot J, Thorpe SR, et al. Effect of collagen turnover on the accumulation of advanced glycation end products. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 39027–39031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haitoglou CS, Tsilibary EC, Brownlee M, et al. Altered cellular interactions between endothelial cells and nonenzymatically glucosylated laminin/ type IV collagen. J Biol Chem 1992; 18: 12404–12407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lohwasser C, Neureiter D, Weigle B, et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end products is highly expressed in the skin and upregulated by advanced glycation end products and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126: 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee EJ, Kim JY, Oh SH. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) promote melanogenesis through receptor for AGEs. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 27848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kueper T, Grune T, Prahl S, et al. Vimentin is the specific target in skin glycation structural prerequisites, functional consequences, and role in skin ageing. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 23427–23436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berge U, Behrens J, Rattan SI. Sugar-induced premature ageing and altered differentiation in human epidermal keratinocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1100: 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jeanmaire C, Danoux L, Pauly G. Glycation during human dermal intrinsic and actinic ageing: an in vivo and in vitro model study. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Huijberts MS, Schaper NC, Schalkwijk CG. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res 2008; 24: S19–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu CH, Yen GC. Inhibitory effect of naturally occurring flavonoids on the formation of advanced glycation endproducts. J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53: 3167–3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ulrich P, Cerami A. Protein glycation, diabetes, and aging. Recent Prog Horm Res 2001; 56: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bolton WK, Cattran DC, Williams ME, et al. Randomized trial of an inhibitor of formation of advanced glycation end products in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Nephrol 2004; 24: 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pageon H, Técher MP, Asselineau D. Reconstructed skin modified by glycation of the dermal equivalent as a model for skin aging and its potential use to evaluate anti-glycation molecules. Exp Gerontol 2008; 43: 584–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang S, Litchfield JE, Baynes JW. AGE-breakers cleave model compounds, but do not break Maillard crosslinks in skin and tail collagen from diabetic rats. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003; 412: 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wada R, Nishizawa Y, Yagihashi N, et al. Effects of OPB-9195, anti-glycation agent, on experimental diabetic neuropathy. Eur J Clin Investig 2001; 31: 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nakamura S, Makita Z, Ishikawa S, et al. Progression of nephropathy in spontaneous diabetic rats is prevented by OPB-9195, a novel inhibitor of advanced glycation. Diabetes 1997; 46: 895–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cefalu WT, Bell-Farrow AD, Wang ZQ, et al. Caloric restriction decreases age-dependent accumulation of the glycoxidation products, N epsilon (carboxymethyl)lysine and pentosidine, in rat skin collagen. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995; 50: B337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dearlove RP, Greenspan P, Hartle DK, et al. Inhibition of protein glycation by extracts of culinary herbs and spices. J Med Food 2008; 11: 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Draelos ZD, Yatskayer M, Raab S, et al. An evaluation of the effect of a topical product containing C-xyloside and blueberry extract on the appearance of type II diabetic skin. J Cosmet Dermatol 2009; 8: 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rutter K, Sell DR, Fraser N, et al. Green tea extract suppresses the age-related increase in collagen crosslinking and fluorescent products in C57BL/6 mice. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2003; 73: 453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tarwadi KV, Agte VV. Effect of micronutrients on methylglyoxal-mediated in vitro glycation of albumin. Biol Trace Elem Res 2011; 143: 717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vasan S, Foiles P, Founds H. Therapeutic potential of breakers of advanced glycation end product-protein crosslinks. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003; 419: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Han AR, Nam MH, Lee KW. Plantamajoside inhibits UVB and advanced glycation end products-induced MMP-1 expression by suppressing the MAPK and NF-ĸB pathways in HaCaT cells. Photochem Photobiol 2016; 92: 708–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Devangelio E, Santilli F, Formoso G, et al. Soluble RAGE in type 2 diabetes: Association with oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2007; 43: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Niu Y, Cao X, Song F, et al. Reduced dermis thickness and AGE accumulation in diabetic abdominal skin. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2012; 11: 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tian M, Qing C, Niu Y, et al. The relationship between inflammation and impaired wound healing in a diabetic rat burn model. J Burn Care Res 2016; 37: e115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Das A, Ghatak S, Sinha M, et al. Correction of MFG-E8 resolves inflammation and promotes cutaneous wound healing in diabetes. J Immunol 2016; 196: 5089–5100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Loughlin DT, Artlett CM. 3-Deoxyglucosone-collagen alters human dermal fibroblast migration and adhesion: implications for impaired wound healing in patients with diabetes. Wound Repair Regen 2009; 17: 739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhu Y, Lan F, Wei J, et al. Influence of dietary advanced glycation end products on wound healing in nondiabetic mice. J Food Sci 2011; 76: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Peppa M, Brem H, Ehrlich P, et al. Adverse effects of dietary glycotoxins on wound healing in genetically diabetic mice. Diabetes 2003; 52: 2805–2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wear-Maggitti K, Lee J, Conejero A, et al. Use of topical sRAGE in diabetic wounds increases neovascularization and granulation tissue formation. Ann Plast Surg 2004; 52: 519–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Niu Y, Xie T, Ge K, et al. Effects of extracellular matrix glycosylation on proliferation and apoptosis of human dermal fibroblasts via the receptor for advanced glycosylated end products. Am J Dermatopathol 2008; 30: 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yavuz D, Tuğtepe H, Cetinel S, et al. Collagen ultrastructure and TGFbeta1 expression preserved with aminoguanidine during wound healing in diabetic rats. Endocr Res 2005; 31: 22943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kim S, Kwon J. Thymosin beta 4 improves dermal burn wound healing via downregulation of receptor of advanced glycation end products in db/db mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1840: 3452–3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chen SA, Chen HM, Yao YD, et al. Topical treatment with anti-oxidants and Au nanoparticles promote healing of diabetic wound through receptor for advanced glycation end-products. Eur J Pharm Sci 2012; 47: 875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pepe D, Elliott CG, Forbes TL, et al. Detection of galectin-3 and localization of advanced glycation end products (AGE) in human chronic skin wounds. Histol Histopathol 2014; 29: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhang Q, O’Hearn S, Kavalukas SL, et al. Role of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in wound healing. J Surg Res 2012; 176: 343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Graves DT, Liu R, Alikhani M, et al. Diabetes-enhanced inflammation and apoptosis–impact on periodontal pathology. J Dent Res 2006; 85: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cook JL, Dzubow LM. Ageing of the skin: implications for cutaneous surgery. Arch Dermatol 1997; 133: 1273–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mulder DJ, Van De Water T, Lutgers HL, et al. Skin autofluorescence, a novel marker for glycemic and oxidative stress-derived advanced glycation endproducts: an overview of current clinical studies, evidence, and limitations. Diabetes Technol Ther 2006; 8: 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Meerwaldt R, Links T, Graaff R, et al. Simple noninvasive measurement of skin autofluorescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005; 1043: 290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tseng JY, Ghazaryan AA, Lo W, et al. Multiphoton spectral microscopy for imaging and quantification of tissue glycation. Biomed Opt Express 2010; 2: 218–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Schurman L. Metformin reverts deleterious effects of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) on osteoblastic cells. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2008; 116: 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pang R, Guan M, Zheng Z, et al. [Effects of metformin on apoptosis induced by advanced glycation end-products and expressions of caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2 in human dermal fibroblasts in vitro]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2015; 35: 898–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

How to cite this article

- Van Putte L, De Schrijver S, Moortgat P. The effects of Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) on dermal wound healing and scar formation: a systematic review. Scars, Burns & Healing, 2016. DOI: 10.1177/2059513116676828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]