Abstract

Burn injuries from corrosive substances have been recognised as a common method of assault in low and middle income countries (LMICs) motivated by various factors. Such injuries often leave survivors with severely debilitating physical and psychological injuries and scars. The number of reported cases of acid assaults within the United Kingdom (UK) appears to be on the rise. As one of the largest regional burn centres in the UK, we have reviewed our experience of chemical burns from assault. This study aims to: (1) review the demographics, incidence and patient outcomes; (2) evaluate the long-term psychosocial support provided; and (3) review current criminal litigation proceedings and preventative legislations in the UK specific to assault by corrosive substances. A 15-year retrospective review of 21 burn injuries from assault with corrosive substances presenting to a regional burn unit was conducted. Victims were mostly young men; male perpetrators were more common. The most common motive cited was assault. The most common anatomical region affected was the face and neck. The number of victims who pursue litigation is disproportionately lower than the number of total cases at presentation. In an effort to better understand the legal considerations surrounding such assaults, we also collaborated with lawyers experienced in this particular field. We hope that our work will help educate healthcare professionals regarding the legal assistance and existing laws available to protect these patients.

Keywords: Assault burns, corrosive substances, legal, legislation, prevention, acid attack, scar

Lay Summary

Burn injuries from corrosive substances can have fatal complications and leave survivors with severely debilitating physical injuries and psychological scars. The incidence of acid assaults appears to have increased in the UK and gained much publicity through widespread news coverage. This prompted us to look at our experience in managing patients who were victims of assault using corrosive substances. Over a 15-year period, we treated 21 people who sustained burn injuries as a result of an assault involving corrosive substances. Five people required hospital admission for the extent of their injuries and required significant burn reconstructive procedures. Interestingly, only nine out of 21 cases initiated a criminal investigation. Only two of the nine cases that initiated criminal investigations proceeded to indictment. In an effort to better understand legal considerations surrounding such assaults, we collaborated with lawyers experienced in this particular field and lay out for the first time the UK landscape of litigation in this complex area. We hope that our work will help educate healthcare professionals of the legal assistance and existing laws present to protect these vulnerable patients.

Introduction

Acid burns have been well recognised as a vicious act of assault among low and middle income countries (LMIC) including India, Iran, Jamaica, Bangladesh and Uganda.1–4 The profile of victims varies accordingly to their cultural background. For instance, victims in South Asia are commonly young women who have rejected a suitor or young wives who have been punished by their husbands or in-laws as a result of dissatisfaction over the marriage dowry.5 In Iran,4 political motivation has driven assaults with homicidal intent towards government officials. Male victims are more common in Jamaica, with marital dispute and jealousy cited to be a driving factor for these crimes of passion. The use of corrosive substances to inflict injury can also be entirely motivated by random criminal acts such as robberies.1

The first reported case of acid attack in Europe was thought to occur as early as the 16th century (see excerpt 1).6,7 On the whole, burn injuries sustained from assault with corrosive substances are relatively uncommon in western societies. Literature describing the incidences of chemical burns from assaults in the western world is limited.8 Acid was not the only agent used. In the United States, household lye (sodium hydroxide) was noted to be a common agent preferred by perpetrators.9–11 Patient demographics also differ with male victims predominating, and assailants were more often women. Domestic disputes are often the motivating factor behind these assaults. In 1990, Beare et al. reported ophthalmic injuries in 64 patients admitted to The Western Ophthalmic Hospital in London12 as a result of chemical assaults inflicted by gangs of male youths from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Excerpt 1 − Acid attack in Europe: A walk through history.

In ancient times, vitriol (containing sulphuric acid) was used to purify gold and fabricate imitation precious metals. It was introduced to Europe in the 16th century and not long after that, one of the first recorded acid assaults occurred in France. Its incidence continued to rise, what was described as ‘a wave of vitriolage’ occurred particularly in France. The term ‘La Vitrioleuse’ was coined gaining popular press coverage as ‘crimes of passion’, perpetrated mostly by women against other women, and fuelled by ‘jealousy, vengeance… and provoked by betrayal or disappointment’. Les Vitrioleuses intended to disfigure their disloyal mate or female rival. During the late 19th century, the image of Vitrioleuses was popularised by Art Nouveau artists. ‘La Vitrioleuse’ by Fernand Pelez is still considered an Art Nouveau masterpiece today.

Regardless of the variation in patient demographics globally, the physical and psychological morbidity of such assaults can be devastating (Figure 1). Patients can be left visibly disfigured, some requiring multiple reconstructive procedures to recreate key facial features. Although there is legislation against such assaults, the proportion of victims who fully pursue criminal charges against their perpetrator is low. We noted this recurrent theme during our literature search14 which led us to review our numbers of assault victims suffering chemical burns treated in a regional burn centre, with the intention of understanding: (1) current epidemiology; (2) some indictors of patient outcomes; and (3) legislation and processes within the UK law available to assist such victims. We collaborated with an independent law firm that has had experience in dealing with acid assaults within the UK. No articles specific to the UK have previously focused on an understanding of legal proceedings for victims wishing to pursue criminal prosecution of the assailant in this patient group.

Figure 1.

Health outcomes of acid attack violence.13

Methodology

From our available database spanning 1 January 2000 up to and including 31 December 2014 (15 years), approximately 680 total chemical burn injuries have been recorded during that period which included both accidental injuries and intentional burns. A retrospective review of all patients coded as sustaining assault related to burn injuries from chemical or corrosive substances on our database was carried out from that 15 year database. A list of 26 patients was generated. The inclusion criteria was all patients who were assaulted with chemical or corrosive substances during that period. The study was registered with our clinical governance department (CA14-135) as an audit and a service evaluation. We obtained medical case-notes, from which information was collected on patient epidemiology, burn details, substances used, gender and relationship of assailant, location of the assault, involvement of psychological support, involvement of police, documentation of likely criminal proceedings and number of successful prosecution. We collaborated with a London-based law firm who has had experience dealing with victims of acid assaults for their perspective on legal proceedings and the UK legislation.

Results

Our initial search revealed 26 patients coded as assault-related burns. Five patients were excluded from this search following detailed review of the presenting history showing that these were actually accidental injuries. We included the remaining 21 patients for analysis of the following areas:

Patient demographics

Burn demographics

Extent of injury, management strategies and length of inpatient stay

Psychological support provided

Circumstances of assault

Patient demographics

The male:female ratio was 15:6. The age range was 16–56 years (mean age, 28.5 years). The proportion of victims aged 25 years or younger was almost twice that in the above 25-year age group. Victims came from various cultural backgrounds such as Caucasian (n = 16), African (n = 3), Oriental (n = 1) and South Asian subcontinent (n = 1). Ten patients (48%) were unemployed, nine (43%) were in employment at the time of the event and two (9%) were students. Four patients had prior history of trauma sustained from another assault. One patient had a history of previous domestic dispute resulting in trauma during the altercation. Only one patient was known to social services prior to the assault. Current trends of assault involve more female victims than male victims compared to a decade ago (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trends of total cases noted every 5 years, with the number of male and female victims described.

Circumstances of assault

A total of 76% (n = 16) cases occurred on the streets, although assaults were also noted to occur at home (14%, n = 3), hostel (5%, n = 1) and pub (5%, n = 1). Concurrent substance abuse such as combination of alcohol and/or recreational drugs by the victims at time of assault was reported in six cases. Seven (33%) of the assailants who carried out the attacks were known to their victims prior to the incident. Eight assailants were documented to be men, one woman and four unknown as they had their faces covered, and in eight cases there was no documentation at all. In 16 cases, there was clear documentation of the patient account indicating a motive for the assault and five cases were random or unprovoked.

Police involvement at presentation was documented in 15 cases (17%). Five cases (24%) self-presented and there was no initial or subsequent police involvement. In one case, it was unclear whether police were involved. Criminal investigation was only initiated in nine cases (43%). Of these, only two cases have successful criminal prosecution thus far. With regard to the Criminal Injuries Compensation Act, only two victims proceeded to make claims.

Burn demographics

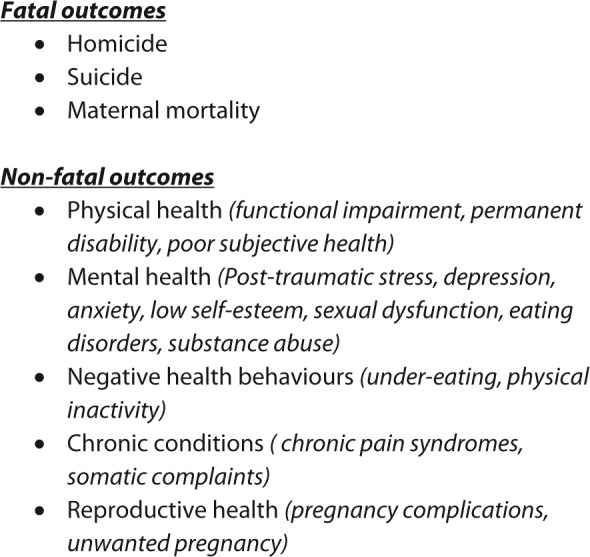

The total burn surface area affected was in the range of 0.3–16% with a median of 1% TBSA. The burn depth was either full thickness or mixed depth type. Acid was the most commonly documented substance used (n = 10), followed by alkali (n = 4), bleach (n = 3), unknown (n = 2) and other (n = 2). In all 21 cases, first aid was given although there was a delay in four patients. Sixteen patients presented immediately to their nearest accident and emergency department while in the other five cases, there was a delay (median, 1 day). Burn injuries sustained during the assault often affected more than a single region of the body, with the face being the commonest area to be affected (18/21), followed by the upper limbs (11/21), neck (8/21), trunk (7/21) and lower limbs (5/21). Many patients had involvement of multiple anatomical sites (Figure 3). Nine patients had eye involvement, all of whom received ophthalmology review acutely (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Chart demonstrating anatomical involvement.

Figure 4.

Chart showing ophthalmic involvement.

Extent of injury, management strategies and length of inpatient stay

Five patients were admitted to hospital as a result of their injuries at initial presentation. Their length of stay in hospital was in the range of 0–41 days with an average of 6.3 days (median, 1 day). One patient also sustained upper limb fractures during the assault. Sixteen patients (76%) were solely managed non-operatively with dressings and outpatient visits. Five patients (24%) required surgical debridement at presentation and wound coverage with autografts and skin substitutes such as Matriderm®.

One patient developed burn wound infection and graft loss, necessitating further surgery. Two patients suffered cartilage loss of an ear as a result of the burn injury. These patients required late repeated burn reconstructive procedures as a result. Of the nine patients who had eye involvement, only one subsequently developed partial loss of sight as a result.

Psychological treatment

Eight of the 21 patients received clinical psychologist review and follow-up. All patients admitted to our burns unit are offered psychosocial support. Patients whose burn injuries were managed at outpatient clinic visits are always referred on to clinical psychology when required or upon patient request. All inpatients were seen by the clinical psychologist. Four of the 16 outpatients received clinical psychologist input. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the total number of cases and the numbers actually receiving psychosocial support is patients refusing to be referred on, but the reasons were not clear. In cases where victims self-presented unaccompanied by the police, they declined review by a clinical psychologist.

Discussion

Approximately 1500 acid assaults are reported worldwide annually.15 Burn injuries from acid attacks have been well described in LMICs. Bangladesh has the highest worldwide incidence of acid violence and acid burns, constituting 9% of its total burn injuries.16 In Pakistan, around 400 acid attacks on women occur annually although this figure may represent an overestimation from non-formal data collection technique.17 Sri Lanka, India, Cambodia and Uganda have also reported cases of acid assaults although its true incidence is difficult to ascertain. This is largely due to problematic reporting mechanisms and under-reporting by victims.

The epidemiology of acid violence varies geographically. Examples from the published literature show that in Bangladesh, victims are often young women who have rejected a potential suitor or new brides punished by their husbands and in-laws over dowry disputes.2 In Cambodia,18 the majority of victims are young mistresses attacked by their lovers’ wives. Acid burns have also been used as forms of violence during robberies, political protestations and, in rare cases, of assassination plots.4 Our series showed a higher proportion of young male victims and male perpetrators, contrary to that seen in LMICs. In Taiwan, victims were mainly women, with a higher proportion of male perpetrators. Marital and financial problems were cited as the most common motive.19 In the United States, victims were generally men and perpetrators were women although motive(s) were unclear.8,14 These findings suggest the demographics of burns from assault using corrosive substances vary geographically and points to complex underlying social and cultural factors relating to both perpetrators and victims.

Any corrosive substance can be used as a weapon in an assault. Acid is commonly used, with sulphuric acid quoted to be a common agent. In LMICs, sulphuric acid is easily obtainable from most car garages at an affordable price to the public.1 Lye, caustic soda and caustic potash have also been described in the literature as potential substances used in assault.10 An accurate description of the substance used is often difficult to ascertain unless there are characteristic features to the burn injury indicative of the acid type such as nitric acid (which forms yellow stains and produces a garlic odour).20 Our review showed that identification of the exact substance used by perpetrators was difficult and the description ‘colourless liquid’ was used. It is therefore important that initial evaluation of the burn wound includes pH measurement, which itself can be challenging particularly in cases where presentation is delayed. In our study, we also found that bleach was frequently used, and household bleach is both cheap and easily accessible.

Despite the vast variation in motives and epidemiology of acid assaults, there are recurrent themes of concern outlined in the existing literature. Acid attacks are malicious attacks with the intent to cause devastating bodily mutilation and functional impairment. The resulting disfigurement can be a constant taunt to the survivors mentally, physically and emotionally. Often, the long-term psychosocial effects are so severe that they can impede the progress of social reintegration following the burn injury. As a result, many victims lead a life as a recluse.19 Although location is not a key factor in social reintegration, we found that these injuries most commonly involved visible and public facing parts of the body such as the face, neck and hands. Our findings mirrored that reported by Faga et al.21

Psychological morbidity of burns survivors have been extensively studied.22,23 Mannan et al. showed that burn injury and the event itself (the assault), are both important contributors to psychosocial outcomes.5 The study also noted lower self-esteem in women who have suffered acid attacks. Anatomical location of the assault, relationship to the assailant and consequent functional limitations have been shown to be predictors of distress.5 Psychosocial support is important as part of burn rehabilitation. Worldwide, charitable foundations exist to offer a vital source of support to these victims beyond their initial injury. In the UK, The Katie Piper Foundation24 (London), Acid Survivor Trust International15 (ASTI) and Domestic Violence UK25 are among charities available to provide support beyond initial injury. Beyond the UK, government organisations (GOs) and non-government organisations (NGOs) exists worldwide to support victims of acid violence (Table 1).

Table 1.

International organisations supporting victims of acid violence.

| Organisation | Role |

|---|---|

| Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO); Cambodia26 | • PAT programme provides financial, counseling, medical, and

legal and advocacy assistance • Reporting of incidences |

| Children’s Surgical Centre (CSC); USA-based NGO27 | • Burn treatment assistance and rehabilitation |

| Cambodian Acid Survivors Charity (CSAC); Cambodia28 | • Surgical, medical and psychological

treatment • Vocational training and social reintegration • Legal assistance and advocacy for legal reform • Awareness through research, education and advocacy |

| Campaign and Struggle Against Acid Attacks on Women (CSAAAW); India29 | • Assists survivors with access to legal, medical and social

services • Works to prevent further attacks |

| Acid Survivors Foundation; Bangladesh30 | • Assistance with treatment, rehabilitation, legal and advocacy for legal reform, increase awareness through research advocacy and prevention measures |

| Naripokkho, Bangladesh31 | • Works to advance situation of women, to struggle against

violence and inequity, lobby for women’s rights • Brought media attention and initiated campaign against acid violence in mid 1990s |

| Acid Survivors Foundation Pakistan ASFP; Pakistan32 | • Stop acid and burn violence and prevent the proliferation of

attacks • Ensure survivors receive the best available medical treatment in the long run • Ensure survivors get justice, exercise their fundamental rights in accordance with the Pakistani constitution and international conventions • Enable survivors to end up as proactive, democratic, empowered and autonomous citizens |

| Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP); Pakistan17 | • Collects statistics from newspaper reports pertaining to acid attacks |

| Human Rights Watch (HRW); International33 | • Investigate and report on human rights violations on global scale |

| Ansar Burney Trust; Pakistan34 | • Medical treatment aid and legal support |

| Acid Survivors Foundation; Uganda[35] | • Funds medical care • Trains and educates community • Police and other agencies • Provides counselling and advocacy |

In 2001, the National Burn Care Review Committee (NBCRC) had acknowledged that psychosocial rehabilitation, which is an integral part in burn care, had been seriously neglected in the UK.36 Following their report, recommendations have been put forward including the need for a named coordinator for psychosocial rehabilitation who is responsible for managing these aspects of care for the burn patient. Since then, improvements have been built upon this principle, including the set-up of psychological care services in various burn units across the nation.36

In our review, nine cases out of a total of 21 resulted in the initiation of a criminal investigation. The number of cases that actually proceed to court cases was difficult to ascertain accurately. We have identified two successful prosecutions that have gained publicity through news coverage.37 One possible explanation for this disparity is the unwillingness of patients to pursue the case or press charges. Several studies have previously reported similar findings.3,38,39 Victims who are experiencing the emotional and mental trauma following an assault may feel unsafe and vulnerable, fearing that pressing charges may provoke further attacks. Lack of knowledge on how to instigate legal proceedings may also account for the low proportion of victims pursuing court action. This is especially important for victims where perpetrators are still ‘out there’.

Acid attacks and the law

Within the UK, the police or hospital are usually the first point of contact and would be able to assist as much as they can. The above-mentioned charities can provide advice and direction for individuals seeking legal support beyond the initial phase of hospital care.

Classification of assaults and expected sequence of litigation events

There is no single law firm dedicated solely to acid assaults prosecutions. We collaborated with a legal firm that has previously dealt with acid assaults.40 These assaults fall into two categories: domestic violence or criminal assault. The ability to deal with domestic violence law or criminal law by any law firm dictates its ability to manage acid assault cases.

The most common setting for chemical attacks to take place is within domestically violent relationships.15 If the crime is committed within a domestic relationship, the survivor could be introduced to domestic violence organisations and thereafter potentially to family law solicitors. Threats of violence originate from the perpetrators who, in order to affirm their control, threaten to throw acid on their partners. A Non-Molestation Order and Occupation Orders from the family courts could potentially be sought in such circumstances.

If the act is carried out and acid is thrown at a victim, then this attack is dealt with as a criminal offence, which is most likely to be considered under one of the following two offences:

Grievous Bodily Harm (GBH): This offence is committed when a person unlawfully and maliciously, with intent to do some grievous bodily harm, or with intent to resist or prevent the lawful apprehension or detainer of any other person, either: wounds another person; or causes grievous bodily harm to another person.41

Attempted Murder:42 This offence is committed when a person does an act that is more than merely preparatory to the commission of an offence of murder, and at the time the person has the intention to kill.43

If the offence committed is GBH, then this will be dealt with in a Crown Court and can result in a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. Criminal sentences of more than 10 years for this offence are rare. However, if acid is used in a further manner, for example, poured down the victim’s throat, this is deemed to be an attempted murder. The sentencing for this varies depending on the nature of the offence and the extent of damage caused. There is arguably no need for any legislative change in the UK unlike other countries as the sentencing powers reflect the severity of the crime.

In 2004 Greenbaum et al.39 suggested that the incidence of acid violence has remained steady. However, from 2006 onwards, the number of reported admission from acid assaults has gradually risen according to NHS data (Table 2).44 The discrepancy could be attributed to better reporting systems for acid assault cases and increased reporting in the media.

Table 2.

Assaults by a corrosive substance as reported by the NHS Information Centre.44

| Year | Admissions |

|---|---|

| 2006–2007 | 44 |

| 2007–2008 | 67 |

| 2008–2009 | 69 |

| 2009–2010 | 98 |

| 2010–2011 | 110 |

Applying for Legal Aid and instigating court proceedings

Entitlement to Legal Aid has recently changed due to the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (2012).45 Up-to-date information is given on the following website: http://www.justice.gov.uk/private-family-matters-legal-aid/victims-domestic-violence.46 If victims wish to apply for Legal Aid to cover the costs of seeking protection from domestic abuse (e.g. a Non-Molestation Order, Occupation Order or Forced Marriage Protection Order) then victims will qualify for Legal Aid subject to a means test.46

Individuals who are threatened with or become victims of acid violence can try and obtain protection from their abuser by applying for a civil injunction or protection order. An injunction is a court order that requires someone to do or not do something. In order to apply for an order, the applicant must be an ‘associated person’ otherwise the matter would not fall under family law.

If the applicant does not fall within the definition of an associated person under the Family Law Act but is being continually harassed, threatened, pestered or stalked after a relationship has ended, they may have grounds to apply for a civil injunction under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. In this way they will still be able to receive protection from the courts.

A Non-Molestation Order is aimed at preventing the abuser from threatening violence against, intimidating, harassing or pestering the victim in order to ensure their safety and wellbeing. An Occupation Order regulates who can live in the family home and can restrict the abuser from entering the surrounding area (e.g. 100 m). A breach of a Non-Molestation Order is a criminal offence and is punishable with up to 5 years’ imprisonment. Breach of an order can result in contempt of court and can be dealt with in the family courts. The perpetrator or respondent who continually harasses the victim can be imprisoned for a period of 2 years following committal in the family courts.

The application is made on Form FL401: Application Form for Non Molestation Order and Occupation Order, supported by a sworn statement. This statement will set out the facts and the reasons for making the application and why the victim protection of the court. The most recent and most traumatic incidents of domestic violence should always be included. This is a short hearing without compulsory notice to the Respondent. In almost all cases it is necessary to get a return hearing date as soon as possible (usually within 1–2 weeks). Sometimes this is necessary because there is a fear that as soon as the Respondent learns about the application, they may cause more harm. The judge then makes a decision (after hearing from the Respondent at this hearing) as to whether the order will continue and the duration of the order. The court rarely makes an Occupation Order at this stage, as this issue is more complex and a further substantive hearing will be needed, with notice to the Respondent.

Even with an order in place, one should not assume that the victim is completely protected. Threats of acid violence are very serious. While a court order can be a deterrent, it may not always stop the respondent/perpetrator from carrying out the acts.

Collaborative efforts and working framework

An integrated public health response with strong formalised partnership between survivors, GOs and NGOs, health authorities and law enforcement can lead to better collaboration and coordination of efforts to end acid violence. Governments should also maintain a zero-tolerance policy in order to eliminate acid violence. Close collaboration with forensic criminologist, psychologist and perpetrators may help develop a better understanding of motivations and analyse root causes of such assaults. Beyond local organisations, such collaborations should venture out to include international and regional working groups that offer a platform for information sharing and raising awareness in preventing acid attack violence.

Education and prevention

Prevention remains key to reducing the incidence of burn injuries. Publicised education campaigns have increased awareness and appear to have reduced the number of attacks in LMICs.47 Some have feared that publicity can lead to an increase in such attacks, but there is no evidence to support this view at this time. Healthcare professionals would benefit from education and information on the available psychosocial and legal support for such assault victims. As the first point of contact in a protected environment such as in hospital, this may be the only opportunity to provide these patients with a setting in which they may feel ‘safe’ enough to accept help. There are dedicated charitable foundations to acid assault survivors within the UK such the KPF and ASTI. Together, these charities offer information on burn scar rehabilitation, support access to quality medical care, assist with survivors’ psychological and social rehabilitation, and advocacy work to prevent further attacks.15,24

Regarding prevention laws, more stringent legislation on the purchase of corrosive substances is needed. Currently in the UK, corrosive substances such as heavy-duty drain cleaners are easily obtainable by the general public from large DIY superstores. While it is impossible to stop the public purchasing such agents freely over the counter, a legal requirement for sellers to record details of every purchase should be implemented. Such a step may assist criminal investigations. We appreciate this may not completely restrict other means of obtaining corrosive substances by other means, such as that from car batteries. Nonetheless, this will reduce the number of available sources for the potential assailant.

Conclusion

Burn injury by assault with corrosive substances is a malicious criminal act intended to cause grievous bodily harm with potentially devastating long-term morbidity to the victim. As healthcare professionals, we have a professional and ethical obligation to provide the best standard of care to our patients. For victims of assaults, this includes offering prompt access to existing legal, psychosocial and external agency support. To prevent these injuries, we recommend stricter legislation on purchase of corrosive substances, which is likely to have a significant impact on reducing future rates of these attacks.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Branday J, Arscott GD, Smoot EC, et al. Chemical burns as assault injuries in Jamaica. Burns 1996; 22(2): 154–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Das KK, Khondokar MS, Quamruzzaman M, et al. Assault by burning in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Burns 2013; 39(1): 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asaria J, Kobusingye OC, Khingi BA, et al. Acid burns from personal assault in Uganda. Burns 2004; 30(1): 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maghsoudi H, Gabraely N. Epidemiology and outcome of 121 cases of chemical burn in East Azarbaijan province, Iran. Injury 2008; 39(9): 1042–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mannan A, Ghani S, Clarke A, et al. Psychosocial outcomes derived from an acid burned population in Bangladesh, and comparison with Western norms. Burns 2006; 32(2): 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shapiro A-L. Breaking the Codes: Female Criminality in Fin-De-Siecle Paris. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harris R. Murders and Madness: Medicine, Law and Society in the Fin-De-Siecle. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Purdue GF, Hunt JL. Adult assault as a mechanism of burn injury. Arch Surg 1990; 125(2): 268–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brodzka W, Thornhill HL, Howard S. Burns: causes and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1985; 66(11): 746–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Milton R, Mathieu L, Hall AH, et al. Chemical assault and skin/eye burns: two representative cases, report from the Acid Survivors Foundation, and literature review. Burns 2010; 36(6): 924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolfort FG, DeMeester T, Knorr N, et al. Surgical management of cutaneous lye burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1970; 131(5): 873–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beare JD. Eye injuries from assault with chemicals. Br J Ophthalmol 1990; 74(9): 514–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heise L, Ellsberg M, Goetemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Population Reports. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krob MJ, Johnson A, Jordan MH. Burned-and-battered adults. J Burn Care Rehabil 1986; 7(6): 529–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Acid Survivor Trust International. http://www.acidviolence.org/index.php/how-we-help/specialist-teams.

- 16. Acid Survivors Foundation. 6th Annual Report. Dhaka: ASF, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP). http://hrcp-web.org/hrcpweb/campaigns/.

- 18. Ly H, Sarom N, Gollogly, et al. 88 Burns operated at the ROSE rehabilitation Centre, Phnom Penh. Paper read at the 7th annual Cambodian Surgical Congress, November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yeong E, Chen MT, Mann R, et al. Facial mutilation after an assault with chemicals: 15 cases and literature review. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997; 18(3): 234–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harchelroad F, Rottinghaus D. Chemical Burns in Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Faga A, Scevola D, Mezzetti MG, et al. Sulphuric acid burned women in Bangladesh: a social and medical problem. Burns 2000; 26(8): 701–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blalock SJ, Bunker BJ, DeVellis RF. Psychological distress among survivors of burn injury: the role of outcome expectations and perceptions of importance. J Burn Care Rehabil 1994; 15(5): 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams EE, Griffiths TA. Psychological consequences of burn injury. Burns 1991; 17(6): 478–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katie Piper Foundation. http://www.katiepiperfoundation.org.uk.

- 25. Domestic Violence UK. http://domesticviolenceuk.org.

- 26. Lim J-A. Violence Against Women in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: LICADHO, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Children’s Surgical Centre (CSC). http://www.csc.org.

- 28. Cambodian Acid Survivors Charity. Helping survivors heal and working to prevent future acid attacks. http://cambodianacidsurvivorscharity.org.

- 29. Campaign and Struggle Against Acid Attacks on Women (CSAAAW) Vs. Department of Women and Child Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Acid Survivors Foundation. http://www.acidsurvivors.org.

- 31. Naripokkho. http://www.copasah.net/naripokkho.html.

- 32. Acid Survivors Foundation Pakistan. http://acidsurvivorspakistan.org/about.

- 33. Human Rights Watch (HRW). http://www.hrw.org.

- 34. Ansar Burney Trust. http://ansarburney.org.

- 35. Acid Survivor Foundation Uganda. asfuganda.org.

- 36. National Burn Care Review 2001: Standards and Strategy for Burn Care. http://www.britishburnassociation.org/downloads/NBCR2001.pdf (2001, accessed 6 April 2015).

- 37. Mary Konye guilty of acid attack on friend Naomi Oni. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-25867695 (2014).

- 38. Mannan A, Ghani S, Clarke A, et al. Cases of chemical assault worldwide: a literature review. Burns 2007; 33(2): 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greenbaum AR, Donne J, Wilson D, et al. Intentional burn injury: an evidence-based, clinical and forensic review. Burns 2004; 30(7): 628–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blava & Co. Solicitors. http://www.legalblavo.co.uk.

- 41. Section 18 of the Offences Against Person Act 1861. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Section 4(1) of the Criminal Attempts Act 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Legal Aid. http://legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/24–25/100.

- 44. Assaults by a corrosive substance as reported by the NHS Information Centre. http://www.dawsoncornwell.com/en/documents/Acid_Violence.pdf page 8 (2015)

- 45. Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46. GOV.UK. Legal Aid. http://www.justice.gov.uk/private-family-matters-legal-aid/victims-domestic-violence.

- 47. Acid Survivors Foundation. Research Advocacy and Prevention. http://www.acidsurvivors.org/Research-Advocacy-and-Prevention (2015).