Abstract

Objective

Calgranulin-C (S100A12) is a new faecal marker of inflammation that is potentially more specific for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) than calprotectin, since it is only released by activated granulocytes. We compared calgranulin-C and calprotectin to see which of the two tests best predicted IBD in children with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

Design

Delayed-type cross-sectional diagnostic study.

Setting and patients

Previously undiagnosed patients aged 6–17 years, who were seen in paediatric clinics in the Netherlands and Belgium, sent in a stool sample for analysis. Patients with a high likelihood of IBD underwent upper and lower endoscopy (ie, preferred reference test), while those with a low likelihood were followed for 6 months for latent IBD to become visible (ie, alternative reference test). We used Bayesian modelling to correct for differential verification bias.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcome was the specificity for IBD using predefined test thresholds (calgranulin-C: 0.75 µg/g, calprotectin: 50 µg/g). Secondary outcome was the test accuracy with thresholds based on receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis.

Results

IBD was diagnosed in 93 of 337 patients. Calgranulin-C had significantly better specificity than calprotectin when predefined thresholds were used (97% (95% credible interval (CI) 94% to 99%) vs 71% (95% CI 63% to 79%), respectively). When ROC-based thresholds were used (calgranulin-C: 0.75 µg/g, calprotectin: 400 µg/g), both tests performed equally well (specificity: 97% (95% CI 94% to 99%) vs 98% (95% CI 95% to 100%)).

Conclusions

Both calgranulin-C and calprotectin have excellent test characteristics to predict IBD and justify endoscopy.

Trial registration number

Keywords: S100A12 protein, S100 proteins, inflammatory bowel disease, screening

What is already known on this topic?

The calprotectin stool test has been promoted as a non-invasive and easy interpretable triage tool to predict inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in children.

A calprotectin concentration below 50 µg/g has been proposed to rule out IBD and not to proceed to endoscopy.

When this threshold is used, a considerable proportion of children and teenagers with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea are exposed to a pointless invasive procedure.

What this study adds?

This large-scale diagnostic study in a real-life cohort of children with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea shows that the new calgranulin-C stool test has significantly better specificity than calprotectin.

When the calprotectin stool test is used, a two-threshold strategy is recommended with concentrations below 50 µg/g to rule out IBD and concentrations above 400 µg/g to rule in IBD and proceed to endoscopy.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are lifelong conditions that often begin in childhood. Suspicion is raised in children and teenagers with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea. Additional red flag symptoms including rectal bleeding, weight loss and anaemia increase the suspicion of the condition. Endoscopic evaluation of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract with biopsies for histology is essential to diagnose IBD and to differentiate Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis and IBD unclassified, start appropriate therapy and prevent progressive bowel damage.1 Many children consider endoscopy and the required bowel preparation to be uncomfortable.2 Identification of children with a low likelihood of IBD would justify a non-invasive ‘watchful waiting’ strategy, while identification of those with a sufficiently high likelihood of IBD would justify urgent referral to specialist services for endoscopy.

In recent years, the stool calprotectin test has been promoted as a safe and easy interpretable triage tool for endoscopy.3 4 Calprotectin is mainly released by neutrophil granulocytes, but other cells including monocytes and epithelial cells do also excrete this protein.5 To date, a calprotectin concentration below 50 µg/g has been proposed to rule out IBD and not to proceed to endoscopy.6 7 However, there are concerns about the mediocre specificity of the test at this threshold, which may give rise to a considerable proportion of children and teenagers proceeding to a pointless invasive procedure.

Calgranulin-C (S100A12) is a less frequently investigated marker of intestinal inflammation that is almost exclusively released by activated granulocytes.5 In previous case–control studies, calgranulin-C showed diagnostic promise with better specificity compared with calprotectin,8–10 but large studies in a prospective cohort with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea are lacking.

The aim of this study was to compare calprotectin and calgranulin-C to see which of the two markers best predicted IBD in children and teenagers with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

Methods

Design

This was an international multicentre, delayed-type, cross-sectional diagnostic accuracy study with a paired design.11 Previously undiagnosed children and teenagers presenting with persistent diarrhoea for more than 4 weeks or chronic or recurrent abdominal pain were screened with the calprotectin stool test (existing test) and with the calgranulin-C test (new test). Confirmation of the target condition (IBD) was based on endoscopy with biopsies (reference standard) or clinical follow-up (alternative reference standard). The study was registered before recruitment of the first participant, and the study protocol has been published in BMJ Open.12

Patients

Patients were recruited from 16 secondary and 3 tertiary level hospitals in the Netherlands and Belgium. They were eligible when aged between 6 years and 17 years. The flow of patients from the first hospital visit to the choice of the reference test was described comprehensively in our published study protocol.12 In brief, during the first hospital visit, baseline characteristics, date of birth, presence of major and minor red flag signs and symptoms for IBD and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were entered on the study website (www.cacatustudie.eu). A stool specimen was collected at home and sent to the hospital laboratory of the coordinating study centre, where it was immediately tested for calprotectin and colon pathogens (including Shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Enteroinvasive E. coli, Campylobacter and Giardia lamblia) with a real-time multiplex PCR technique. Residual faeces was stored at −80°C for calgranulin-C batch testing at a later stage.

Assays

Stool calprotectin concentrations (μg/g) were measured with the fCAL ELISA (BÜHLMANN Laboratories AG, Schönenbuch, Switzerland) and stool calgranulin-C concentrations (μg/g) with the commercially available Inflamark ELISA (CisBio Bioassays, Codolet, France), both on a Dynex DS2 Automated ELISA System (Alpha Labs, Easleigh, UK) in the same laboratory. The extraction and measuring technique of calgranulin-C was previously described in detail.13 In discordant pairs (ie, increased calprotectin and normal calgranulin-C, or vice versa), we did a post hoc analysis of potential viral causes (adeno, entero, astro, rota, noro, parecho and sapovirus). Laboratory technicians were blinded for symptoms filled in on the website. The attending paediatricians were informed of the calprotectin and PCR result for bacteria and G. lamblia, but they were blinded for the calgranulin-C and PCR result for viruses. The predefined thresholds used in this study were 50 µg/g for calprotectin and 0.75 µg/g for calgranulin-C.

Reference tests

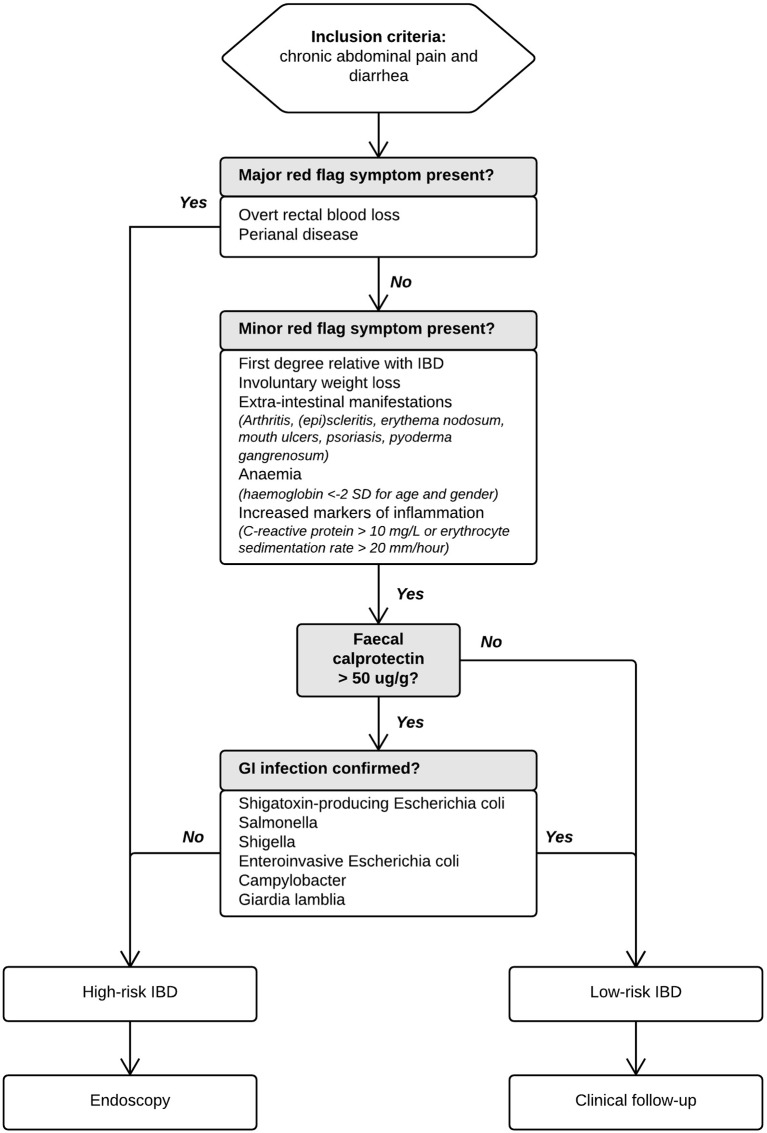

We used an automated IBD Risk Stratifier (figure 1) to advice paediatricians whether patients should proceed to endoscopy (the preferred reference standard) for verification of IBD, or whether they should be followed up clinically for possible latent IBD to become visible (the alternative reference standard). Paediatricians could deviate from this advice for documented clinical reasons. Endoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia by an experienced paediatric gastroenterologist in one of six participating centres. Both upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts were evaluated according to the revised Porto criteria,14 and biopsies were taken from every bowel segment. Histopathological examination was performed by experienced histopathologists. Endoscopists and histopathologists had access to clinical information and calprotectin results but were blinded for the results of the calgranulin-C test. In case patients were assigned to the alternative reference standard, they were re-evaluated using the IBD Risk Stratifier until 6 months after inclusion. In case the initial risk stratum changed to ‘high-risk’, endoscopy was performed ultimately.

Figure 1.

Algorithm explaining the multistep IBD Risk Stratifier used to standardise the assignment of patients to either endoscopy or clinical follow-up. GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, V.22.0 for Windows) and presented with GraphPad Prism (V.5 for Windows (San Diego, California, USA)). Diagnostic accuracy measures (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value) were calculated for both the high-risk and low-risk stratum using predefined thresholds, as well as optimal thresholds (defined as the most upper left data point in the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve). Since we used both endoscopy and clinical follow-up as reference standard, with the latter being less accurate-, we used a Bayesian correction method to adjust for differential verification bias.15–17 This method takes into account the verification pattern as well as bias due to imperfection of the clinical follow-up in a single model. The method requires specifying the verification pattern and giving a best guess of the accuracy of both reference standards in the form of a prior distribution. We assumed that endoscopy had 95%–100% sensitivity and 95%–100% specificity to diagnose IBD and that clinical follow-up had a sensitivity of 80%–100% and a specificity of 60%–80% to diagnose latent IBD. Our inferences are based on the posterior distributions calculated using JAGS (‘Just Another Gibbs Sampler’), a free program licenced under GNU General Public License.18 The R-package script is provided in online supplementary data 1. The sample size calculation was previously described.12

archdischild-2017-314081supp001.docx (15KB, docx)

Human subjects protection

This study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was conducted with the approval of the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center in Groningen (METc 2013/503) and Antwerp University Hospital (14/40/407). All participants aged 12 years and above and their legal guardians gave informed consent to use data generated by routine medical care. The data were collected and recorded by the investigators in such a manner that subjects could not be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects.

Results

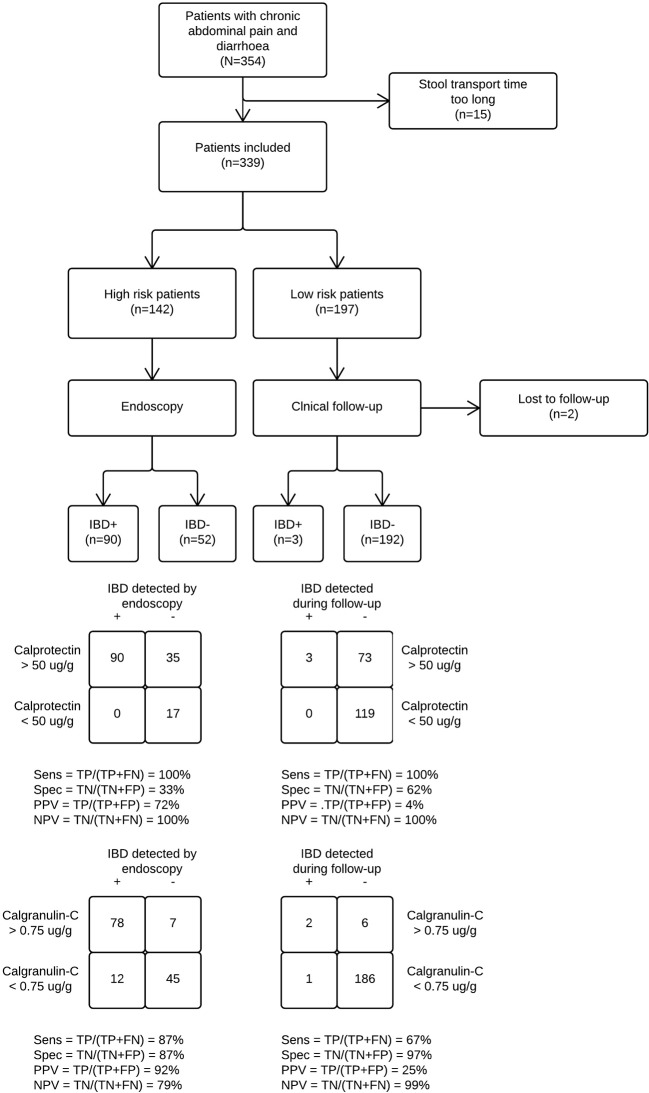

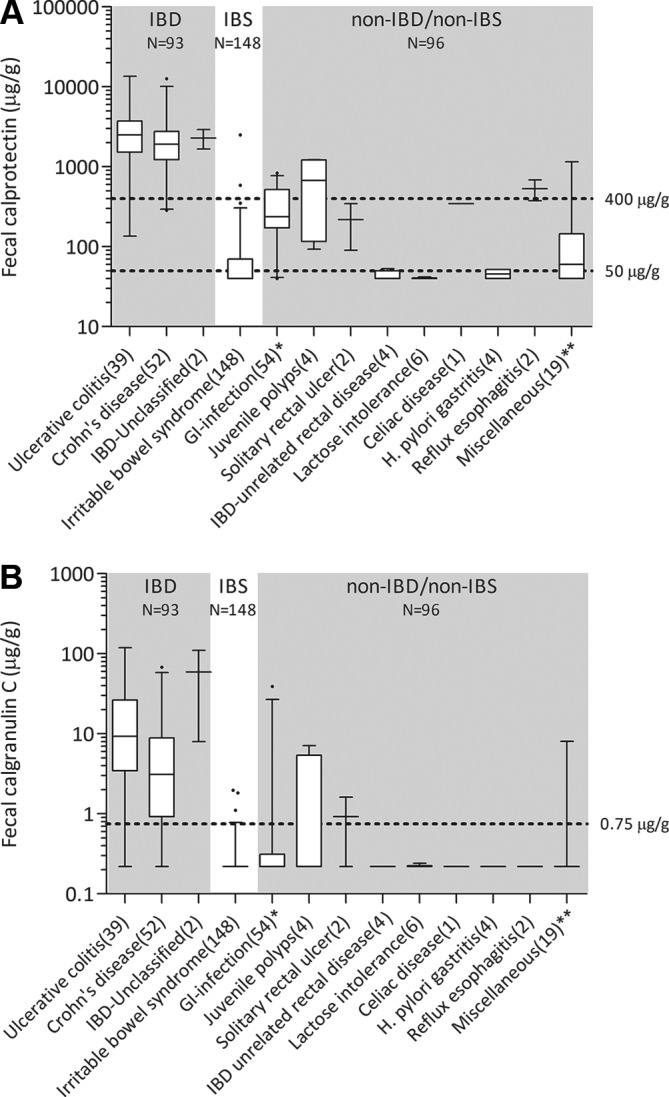

A total number of 354 children and teenagers with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea were recruited into the study between September 2014 and September 2016, and 337 were included in the final analysis. In the early stages, 142 patients proceeded to endoscopy, while 195 were assigned to clinical follow-up. Another 19 children from the low-risk group were referred for endoscopy at a later stage. Eventually, 48% of patients in the study cohort (161 of 337) underwent endoscopy, of which 93 were diagnosed with IBD. The patient study flow is shown in figure 2. Baseline characteristics are presented in table 1. The patients in the high-risk stratum were older, had more red flag symptoms and higher calprotectin concentrations than those in the low-risk stratum. Three patients who were initially in the low-risk stratum were later found to have IBD. All three had elevated faecal calprotectin concentrations (range 340–480 µg/g) and a positive PCR result. Ongoing or worsening symptoms despite eradication of the pathogen made the clinician decide to proceed to endoscopy. The distributions of calprotectin and calgranulin-C values per final diagnosis are shown in figure 3.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram showing differential verification bias. We compared calgranulin-C and calprotectin to see which of the two stool tests best predicted IBD in children with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea. Patients stratified by their paediatrician as high risk for IBD underwent endoscopy. Those with a low predicted risk were followed for 6 months. The probability that a patient truly had IBD given that they were in the high-risk stratum was 63%. Likewise, the probability that a patient in the low-risk stratum was eventually diagnosed with IBD was 1.5%. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea stratified into high and and low risk for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

| Characteristics | High risk (n=142) | Low risk (n=195) |

| Reference test | Endoscopy | Clinical follow-up |

| Demographics | ||

| Median age in years (IQR) | 14 (11–15) | 12 (9–14) |

| Male gender | 67 (47) | 112 (57) |

| Major red flag symptoms | ||

| Overt rectal blood loss | 90 (63) | 0 (0) |

| Perianal disease (superficial anal fissures excluded) | 20 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Minor red flag symptoms | ||

| Weight loss or linear growth deceleration | 52 (37) | 47 (24) |

| Extraintestinal symptoms (including arthritis) | 20 (14) | 13 (7) |

| Family history of IBD | 12 (9) | 18 (9) |

| Anaemia (haemoglobin <−2 SD for age and gender) | 56 (39) | 19 (10) |

| Increased markers of inflammation (C reactive protein >10 mg/L or erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/hour) | 58 (41) | 10 (5) |

| Stool test | ||

| Increased calprotectin (>50 µg/g) | 125 (88) | 76 (39) |

Values are number (%) unless otherwise stated.

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plot for calprotectin (A) and calgranulin-C (B) concentrations per diagnosis. Whiskers represent the 95% CI. Number of cases in brackets. *The GI infection group had either bacterial colon pathogens or Giardia lamblia. **The miscellaneous group included bile-salt diarrhoea (n=1), haemolytic uremic syndrome (n=1), Mediterranean fever (n=1), fructose overload (n=1), spondylarthropathy (n=1), Hirschsprung’s disease (n=1) and allergic enterocolitis (n=1). The remaining 12 were ‘non-IBD, not otherwise specified’. GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

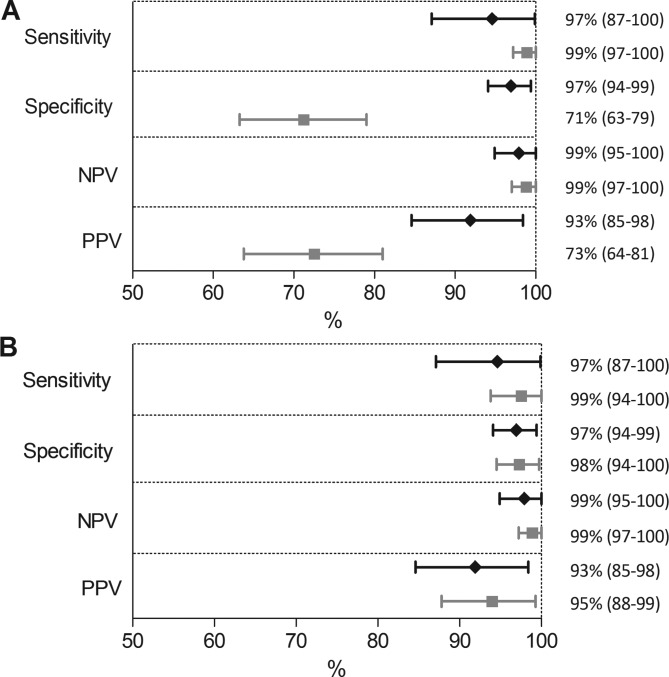

Predefined thresholds

Figure 4A shows the diagnostic accuracy measures based on predefined thresholds for calprotectin (50 µg/g) and calgranulin-C (0.75 µg/g), calculated with the Bayesian correction method. In this analysis, calgranulin-C has significantly better specificity (97.3% (95% credible interval (CI) 94.1% to 99.4%) vs 71.3% (95% CI 63.3% to 79.0%)) and better positive predictive value (92.7% (95% CI 84.6% to 98.4%) vs 72.7% (95% CI 63.8% to 81.0%) compared with calprotectin. The numerical data are shown in online supplementary file 2.

Figure 4.

Diagnostic accuracy measures of the calprotectin (grey square) and calgranulin-C test (black diamond) to diagnose IBD in children. Graph A shows the results when predefined thresholds are used (50 µg/g and 0.75 µg/g, respectively). Graph B shows the results when ROC-based optimal thresholds (400 µg/g and 0.75 µg/g) are used. Whiskers represent the 95% credible interval. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

archdischild-2017-314081supp002.docx (16.6KB, docx)

Optimal (ROC-based) thresholds

The optimal (ROC-based) threshold for calprotectin was 400 µg/g, while the optimal threshold of calgranulin-C was equal to the predefined threshold (0.75 µg/g). The difference in specificity and positive predictive value disappeared when optimal thresholds were compared. A graphical representation of the equivalence between calprotectin and calgranulin-C for the complete study cohort (verified with either reference test) is shown in figure 4B. ROC curves are presented in supplementary file 3.

archdischild-2017-314081supp003.docx (98.9KB, docx)

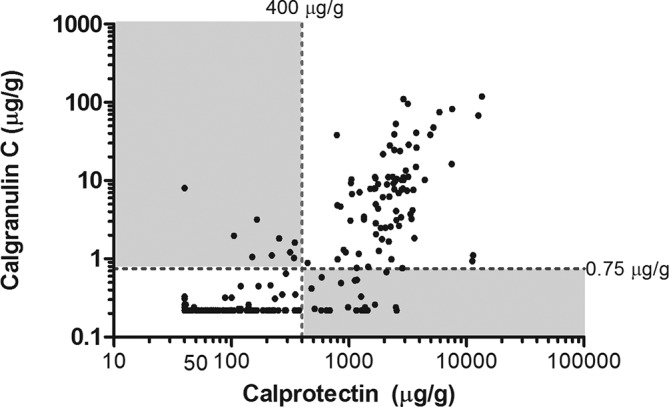

Concordant versus discordant pairs

Figure 5 shows that 306 of 337 pairs of calprotectin and calgranulin-C results were concordant (91%). Discordant pairs (n=31 (9%)) are described in detail in supplementary file 4. Thirteen children with a discordant result were diagnosed with IBD. Two cases were missed with the calprotectin test (threshold 400 µg/g) and 11 cases were missed with the calgranulin-C test (threshold 0.75 µg/g).

Figure 5.

Scatter plot showing concordant and discordant pairs of calprotectin and calgranulin-C measurements. The broken lines represent the ROC-based optimal thresholds for calprotectin (400 µg/g) and calgranulin-C (0.75 µg/g). White fields represent concordant pairs (91%), while grey fields represent discordant pairs (9%). ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

archdischild-2017-314081supp004.docx (18.4KB, docx)

Discussion

The clinical presentation of paediatric IBD is frequently non-specific and overlaps with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Early differentiation is important to avoid delay in proceeding to endoscopy on the one hand and to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures on the other. The mere existence of this trade-off means that a non-invasive and highly discriminative test is needed. We compared the calprotectin and calgranulin-C stool test to see which of the two markers best predicted IBD in children and postulated that the latter probably had better specificity. In this large-scale paediatric diagnostic accuracy study on markers of intestinal inflammation, we show that calgranulin-C has better specificity for IBD than calprotectin, provided the use of common thresholds. When optimal (ROC-based) thresholds are used (ie, calprotectin: 400 µg/g; calgranulin-C: 0.75 µg/g), both tests have exceptionally high sensitivity and specificity to diagnose IBD.

Comparison with existing literature

Well-designed studies on the discriminative power of calgranulin-C are scarce. An Australian research team previously reported on a study comparing calprotectin and calgranulin-C.9 They obtained stool samples from 61 children (2–16 years old) who presented with gastrointestinal symptoms prior to admission for gastrointestinal endoscopy. The predefined threshold used for calgranulin-C in their study cohort (10 µg/g) was substantially higher than the one we used (0.75 µg/g).8 13 The difference is likely to be explained by differences in assays and selection of patients. We included a fair amount of patients that did not proceed to endoscopy, which increases the applicability of our results for populations seen in non-specialised centres. An important methodological flaw in the Australian study was the omission of a fair comparison of optimal thresholds for both markers, which may have resulted in an overinterpretation of calgranulin-C test accuracy.

Several recently published meta-analyses have shown that the calprotectin stool test has good negative predictive (‘rule-out’) value at the commonly used threshold (50 µg/g).3 4 6 A large share of the studies included in these meta-analyses had a case–control design that gives rise to spectrum bias and overestimation of test accuracy relative to the real-life practice.19 We avoided spectrum bias and therefore expected to find more modest accuracy measures than previously reported. Contrary to our expectations, we found that the good rule-out value of calprotectin still holds in a heterogeneous study population with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

At the threshold of 50 µg/g, the specificity of the calprotectin test for the detection of IBD (71%) was comparable with previously reported values. The ROC-based optimal threshold was higher than in previously reported papers. We used the calprotectin ELISA assay of BÜHLMANN Laboratories, which is known to report higher concentrations than the Immunodiagnostik and Eurospittal assays.20 This so-called between-assay variability indicates the need for assay standardisation. In the meantime, each laboratory should investigate transferability of the manufacturer’s thresholds to its patient population and, if necessary, determine its own local thresholds to optimally identify IBD and avoid the need for further costly and invasive investigations.

Strengths and limitations

This large-scale, multicentre, cross-border accuracy study better reflects ‘real-life’ practice than any other previously published study on stool tests for screening and selecting children for endoscopy. We used an automated IBD Risk Stratifier to standardise the assignment of patients to either the high-risk or low-risk stratum. The cooperation of both secondary and tertiary level hospitals in this study promotes the generalisability of our results and conclusions.

The attending paediatricians were not blinded for the calprotectin results. This led to a deviation from the automated advice of the IBD Risk Stratifier in 25% of cases. In supplementary file 5, we show that this especially happened in the calprotectin grey zone between 50 µg/g and 400 µg/g. Knowledge of the calprotectin concentration also led to a diagnostic work-up bias that is usually the case in screening studies where only patients with a positive index test result move on to the reference standard. We reduced this bias by following the low-risk patients for 6 months for possible latent IBD to become visible. One might argue that this observation period was not sufficiently long, but we are confident that the majority of initially missed cases with IBD would become apparent within this time.

archdischild-2017-314081supp005.docx (811.1KB, docx)

Clinical implications

Both calprotectin and calgranulin-C have excellent test characteristics to predict IBD in children and teenagers with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea and justify endoscopy. In this inception cohort, the calprotectin action threshold for proceeding to endoscopy is around 400 µg/g, and this underlines the relevance of using a ‘two-threshold strategy’ as proposed in several publications.7 21–23 The grey zone between the commonly used threshold of 50 µg/g that demarcates the normal range and the action threshold gives room for shared decision making with the patient and his or her parents, in which presence of major red flag symptoms and impact on daily functioning of the child may additionally guide management. One can opt for watchful waiting with monthly monitoring of stool calprotectin or decide to move on to endoscopic evaluation. When calprotectin concentrations are truly out of range, and gastrointestinal infections and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use are excluded, the patient should proceed to endoscopy to rule in IBD. A two-threshold strategy does not seem to be of added value when the calgranulin-C stool test is picked as the triaging tool of preference.

Stool markers are of great help to distinguish IBD from IBS in children with only minor red flag symptoms. When children present with major red flag symptoms of IBD, they will be referred for endoscopy regardless of the stool marker result. There is no added value of stool testing for triaging purposes in this category, although the knowledge of a baseline calprotectin concentration is useful for monitoring the response to treatment. Physicians should take note that different patient populations and different test assays may lead to variations in thresholds.20 21 24

Conclusions

Measuring calprotectin or calgranulin-C concentrations in stool is a useful triage tool for identifying patients who are most likely to need endoscopy for suspected IBD. The discriminative power to safely exclude the disease (specificity) is significantly better than previously reported. When the optimal ROC-based thresholds are used (calprotectin: 400 µg/g; calgranulin-C: 0.75 µg/g), both tests perform equally well in secondary and tertiary level hospitals.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all patients and care professionals who contributed to this study, in particular J Homan-van der Veen (Deventer Hospital), O Norbruis (Isala Clinic), S van Dorth (Tjongerschans), T de Vries (Medical Center Leeuwarden), B Delsing (Treant Zorggroep Hoogeveen), L van Overbeek (Treant Zorggroep Emmen), A Kamps (Martini Hospital Groningen), M Wilsterman (Nij Smellinghe Drachten), G Meppelink (Treant Zorggroep Stadskanaal), H Knockaert (Admiraal de Ruyter hospital Goes), M Claeys (

St. Vincentiushospital Antwerp) and the

technicians of the Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Microbiology at the University Medical Center Groningen.

Footnotes

Contributors: PFvR conceived the study. AH, EVdV, AMK and PFvR initiated the study design. PFvR is the grant holder. AH conducted the primary statistical analysis. DvR conducted the Bayesian modelling. SVB, TZH, ZY, GG-dJ and RS contributed more than 5% of the total number of participants. AH and PFvR drafted the first version of the article. All other authors revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from CisBio Bioassay (producer of Inflamark).

Disclaimer: Neither company had a role in the design, execution, analyses, and interpretation of the data, or in the decision to submit the results.

Competing interests: PFvR and AH received financial support from BÜHLMANN Laboratories AG (Schönenbuch, Switzerland) for other ongoing trials.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center in Groningen (METc 2013/503) and Antwerp University Hospital (14/40/407).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data sharing is available on request.

Collaborators: CACATU consortium.

Author note: Study protocol: Published in BMJ Open 2017;7:e015636.

References

- 1. Oliveira SB, Monteiro IM. Diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease in children. BMJ 2017;357:j2083 10.1136/bmj.j2083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turner D, Benchimol EI, Dunn H, et al. Pico-Salax versus polyethylene glycol for bowel cleanout before colonoscopy in children: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy 2009;41:1038–45. 10.1055/s-0029-1215333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Day AS, et al. Use of laboratory markers in addition to symptoms for diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:984–9. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Henderson P, Anderson NH, Wilson DC. The diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:637–45. 10.1038/ajg.2013.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foell D, Wittkowski H, Roth J. Monitoring disease activity by stool analyses: from occult blood to molecular markers of intestinal inflammation and damage. Gut 2009;58:859–68. 10.1136/gut.2008.170019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Reitsma JB, et al. Noninvasive Tests for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152126–126. 10.1542/peds.2015-2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heida A, Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, et al. Avoid Endoscopy in Children With Suspected Inflammatory Bowel Disease Who Have Normal Calprotectin Levels. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:47–9. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Jong NS, Leach ST, Day AS. Fecal S100A12: a novel noninvasive marker in children with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:566–72. 10.1097/01.ibd.0000227626.72271.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sidler MA, Leach ST, Day AS. Fecal S100A12 and fecal calprotectin as noninvasive markers for inflammatory bowel disease in children. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:359–66. 10.1002/ibd.20336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van de Logt F, Day AS. S100A12: a noninvasive marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. J Dig Dis 2013;14:62–7. 10.1111/1751-2980.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knottnerus JA, Muris JW. Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study : Knottnerus JA, Buntinx F, The evidence based of clinical diagnosis: theory and methods of diagnostic research. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009:42–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heida A, Van de Vijver E, Muller Kobold A, et al. Selecting children with suspected inflammatory bowel disease for endoscopy with the calgranulin C or calprotectin stool test: protocol of the CACATU study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015636 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heida A, Kobold ACM, Wagenmakers L, et al. Reference values of fecal calgranulin C (S100A12) in school aged children and adolescents. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;56:126–31. 10.1515/cclm-2017-0152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58:795–806. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Naaktgeboren CA, de Groot JA, van Smeden M, et al. Evaluating diagnostic accuracy in the face of multiple reference standards. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:195–202. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Groot JA, Dendukuri N, Janssen KJ, et al. Adjusting for differential-verification bias in diagnostic-accuracy studies: a Bayesian approach. Epidemiology 2011;22:234–41. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318207fc5c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Naaktgeboren CA, de Groot JA, Rutjes AW, et al. Anticipating missing reference standard data when planning diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2016;352:i402 10.1136/bmj.i402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Plummer M. JAGS: A program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. 124 Vienna, Austria: Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Statistical Computing, 2003:124–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:25 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitehead SJ, French J, Brookes MJ, et al. Between-assay variability of faecal calprotectin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. Ann Clin Biochem 2013;50:53–61. 10.1258/acb.2012.011272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Sloovere MMW, De Smet D, Baert FJ, et al. Analytical and diagnostic performance of two automated fecal calprotectin immunoassays for detection of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:1564–73. 10.1515/cclm-2016-0796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Kollen BJ, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Fecal Calprotectin for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Primary Care: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:437–45. 10.1370/afm.1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oyaert M, Trouvé C, Baert F, et al. Comparison of two immunoassays for measurement of faecal calprotectin in detection of inflammatory bowel disease: (pre)-analytical and diagnostic performance characteristics. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014;52:391–7. 10.1515/cclm-2013-0699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Labaere D, Smismans A, Van Olmen A, et al. Comparison of six different calprotectin assays for the assessment of inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterol J 2014;2:30–7. 10.1177/2050640613518201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

archdischild-2017-314081supp001.docx (15KB, docx)

archdischild-2017-314081supp002.docx (16.6KB, docx)

archdischild-2017-314081supp003.docx (98.9KB, docx)

archdischild-2017-314081supp004.docx (18.4KB, docx)

archdischild-2017-314081supp005.docx (811.1KB, docx)