ABSTRACT

Anthraquinone dye represents an important group of recalcitrant pollutants in dye wastewater. Aspergillus sp XJ-2 CGMCC12963 showed broad-spectrum decolorization ability, which could efficiently decolorize and degrade various anthraquinone dyes (50 mg L−1) under microaerophilic condition. And the decolorization rate of 93.3% was achieved at 120 h with Disperse Blue 2BLN (the target dye). Intermediates of degradation were detected by FTIR and GC-MS, which revealed the cleavage of anthraquinone chromophoric group and partial mineralization of target dye. In addition, extracellular manganese peroxidase showed the most closely related to the increasing of decolorization rate and biomass among intracellular and extracellular ligninolytic enzymes. Given these results, 2 possible degraded pathways of target dye by Aspergillus sp XJ-2 CGMCC12963 were proposed first in this work. The degradation of Disperse Blue 2BLN and broad spectrum decolorization ability provided the potential for Aspergillus sp XJ-2 CGMCC12963 in the treatment of wastewater containing anthraquinone dyes.

KEYWORDS: anthraquinone dyes, Aspergillus, degradation pathway, ligninolytic enzymes, textile effluents

Introduction

Synthesis dyes belong to high stability xenobiotic compounds, which are used extensively in many industries, especially in textile dyeing and printing industry.1 Among various synthesis dyes, anthraquinone dyes constitute the second largest class of textile dyes which are characterized by the presence of chromophoric group caused by the interaction of stretching vibration of C = O conjugated with C = C.2,3 The release of effluents containing anthraquinone dyes into environment has caused more and more dissatisfaction due to the toxic and carcinogenic properties of dyes and their metabolites.4,5 Therefore, it's necessary to remove dyes from wastewater before discharge into environment.

Nowadays, biologic treatment technology has increasingly aroused people attention, which is a lower-cost and environment friendly alternative compared with conventional physic-chemical treatment technologies.6 Microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, algae and yeasts that played key roles in efficiently decolorizing a wide range of dyes had been reported previously.7-10 Among these microorganisms, bacteria were widely studied for dyes decolorization and its decolorization mechanism mainly relied on various oxidation-reduction enzymes.11-13 Unfortunately, intermediates that degraded incompletely by bacteria such as aromatic amines were reported to be more mutagenic and carcinogenic, this limited the application of a large scale of bacteria.14 The decolorization function of fungi has been well researched recently, especially white rot fungi. Aspergillus, such as Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus versicolor and Aspergillus niger, had also been confirmed to decolorize synthesis dyes through adsorption and/or degradation.15-17 For instance, immobilized Aspergillus flavus was found to biodegrade anthraquinone dye Drimarene blue K2RL and convert the parent toxic dye into less toxic.18 Nevertheless, Aspergillus niger SA1, Aspergillus fumigatus XC6 and Aspergillus fumigatus were reported to decolorize anthraquinone dyes only by bioadsorption,19-21 which was far from the final step of decolorization. Therefore, the decolorization and degradation of anthraquinone dyes with specific contaminant-degrading fungi strains would be a promising alternative.

Some complex and non-specific intracellular and extracellular enzymes produced by fungi had been found to obviously enhance the degradation of complex dyes effluent and achieve eco-friendly process, such as laccase, lignin peroxidase and manganese peroxidase.22,23 Among, laccase is polyphenol oxidase containing multi-copper proteins that catalyze the oxidation of a great variety of phenolic and non-phenolic compounds just need molecular oxygen as a co-substrate; the catalytic mechanism of lignin peroxidase is a series of free radical chain reactions started by microorganism generated by H2O2, which is described as “ping pong” mechanism; manganese peroxidase is an oxidoreductive enzyme that oxidizes Mn2+ to Mn3+, which in turn capable to oxidize a variety of phenolic compounds.24 What's more, some fungi even could partially or completely mineralize dyes which achieved really green technology.10 Bellou et al. reported that the fungi strain Zygomycetes could significantly remove phenolic from olive mill wastewater, which dramatically reduced the toxicity of effluent.25 As previously mentioned, there were relatively little reports about the biodegradation of wastewater containing anthraquinone dyes by microorganism, let alone the degraded pathway of anthraquinone dyes.26-28 Therefore, it's necessary to investigate possible degradation pathway of anthraquinone dyes by any newly specific strain, which would provide useful information on anthraquinone dyes' biodegradation.

In this work, various anthraquinone dyes were decolorized by Aspergillus sp XJ-2 CGMCC12963 (XJ-2), which was screened and identified with the decolorization and degradation ability of Disperse Blue 2BLN.29 Additionally, Disperse Blue 2BLN was chosen as the model dye for further investigating the possible degradation pathways of anthraquinone dyes by XJ-2 via UV-vis, FTIR, GC-MS analysis, and enzyme activities assays.

Results and discussion

Broad-spectrum of decolorization

Most of fungi screened for decolorization were valid for limited dyes. XJ-2 was also found with the decolorization ability with Disperse Blue 2BLN at the beginning. The broad-spectrum of decolorization by XJ-2 was then determined in this work. As it shown in Fig. 1, XJ-2 showed relatively high efficiency for aerobically decolorizing 6 anthraquinone dyes which were often presented in contaminated industrial wastewater. The decolorization efficiency of Reactive Brilliant Blue and Mordant Red 3 by XJ-2 were faster than that of other dyes, which reached respectively 96.6% and 96.2% at 72 h. Among 6 anthraquinone dyes, Mordant Red 3 achieved the maximum decolorization rate of 99.6% at 120 h. Even the decolorization rate of Bromamine Acid could reach 75.6% within 120 h. Osma et al. reported that the decolorization of single anthraquinone dye Remazol Brilliant Blue R and its decolorization rate only reached on 44% within 48 h.28 Ardag Akdogan et al. also reported that the biodecolorization of Remazol Brilliant Blue R (20 mg L−1) and its decolorization rate arrived at 100% within 240 h.31 Compared with previous literatures, XJ-2 was demonstrated with strong and broad spectrum and high efficiency of decolorization to various anthraquinone dyes. Additionally, considering that relatively simple chemical structure and higher decolorization efficiency, Disperse Blue 2BLN was chosen as the model dye for further investigating the possible degradation pathways of anthraquinone dyes by XJ-2 via UV-vis, FTIR, GC-MS analysis, and enzyme activities assays.

Figure 1.

Decolorization of various anthraquinone dyes by XJ-2.

UV-vis analysis

It's universally acknowledged that decolorization of dyes by microorganisms might be adsorption or catabolism, to investigate the possible decolorization mechanism of Disperse Blue 2BLN, UV-vis spectra (340–700 nm) of supernatants at different time intervals were shown in Fig. 2. It exhibited that the intensity at 567 nm (characteristic absorbance wavelength) remarkably decreased and reached virtually zero after 120 h, where its maximum decolorization rate reached 93.3%. Additionally, according to photos of fungus balls in Erlenmeyer flask (Fig. 3), it could easy to see the color difference during the decolorization process of Disperse Blue 2BLN. Mycelium adsorption played a major role during the prophase of decolorization. The disappearance of color in pellets indicated the biodegradation of Disperse Blue 2BLN with XJ-2. Therefore, it could be presumed that the decolorization of Disperse Blue 2BLN might due to biodegradation accompanying with bioadsorption.

Figure 2.

UV-vis spectra of Disperse Blue 2BLN and its intermediates during the decolorization by XJ-2 (A: 0 h, B: 24 h, C: 72 h, D: 120 h).

Figure 3.

The color comparison of fungus balls during decolorization by XJ-2 (Left: 24 h; Right: 120 h).

FTIR analysis

To further investigate the possible pathway of the dye decolorization, pretreated Disperse Blue 2BLN and aliquots obtained at different time intervals during decolorization process were scanned in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 wave numbers using FTIR. Results were shown in Fig. 4. The disappearance of peak approximately at 1900–1700 cm−1 evidenced that the anthraquinone chromophoric group was cleaved in 120 h, which indicated the stretching vibration of C=O conjugated with C=C. At the time of 72 h and 120 h, the characteristic peak of CO2 appeared typically on the wave number between 2400 and 2300 cm−1 which could be one of evidences on the partial mineralization of Disperse Blue 2BLN. Meanwhile, the broken of arylamine compounds was manifested by vanish of the peak at 1100–1000 cm−1 at time of 120 h, indicating aromatic C-NH2 stretching vibration. In addition, the peak at 1300–1200 cm−1 representing C-O-C stretching vibration gradually weakened during the process of decolorization, indicating the further degradation of intermediates. The strong peak at 3500–3400 cm−1 displayed -OH stretching vibration, characteristic absorption peak at 3000–2900 cm−1 revealed aromatic ring C-H stretching vibration, the peak at 1500–1400 cm−1 was attributable to aromatic C = C stretching frequency, and peak at 800 cm−1 displayed the vibration of benzene ring, which peaks existing might demonstrate the existence of benzene and its derivative.32

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of Disperse Blue 2BLN and its intermediates during the decolorization by .XJ-2 (A: 0 h, B: 24 h, C: 72 h, D: 120 h).

GC-MS analysis

GC-MS was also used to detect the new metabolites and confirm the pathway of Disperse Blue 2BLN removal by XJ-2. Fig. 5 showed the mass spectra of 7 different metabolites. At the time of 72 h, the product in the Fig. 5D with a mass peak of 167 ([M−1]) was concluded to be 2-(N-methyl-p-phenylenediamine) ethanol at retention time of 34.558 min. The m/z peak of 278 was identified as dibutyl phthalate in the Fig. 5B at the retention time of 47.232 min. And the m/z peak of 292 ([M−1]) in the Fig. 5A was confirmed as methyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate at retention time of 50.138 min. At the time of 120 h, ethyl propionate first was concluded at retention time of 3.905 min with m/z ion peak of 102 ([M−1]) in Fig. 5G, hydroquinone was confirmed in the Fig. 5F at retention time of 24.556 min with m/z ion peak of 110 ([M−1]), the m/z peak of 206 ([M−1]) was concluded to be 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol in the Fig. 5C, and the m/z peak of 146 ([M−1]) was 1,3-indanone in the Fig. 5E at retention time of 47.232 min. D. Rajkumar also reported the existence of 1,3-indanone (m/z 146) in the metabolites of ozonation RB-19 by electrochemical degradation.33 And dibutyl phthalate (m/z 278) was also found to be one of degradation products of anthraquinone dyes by ozone oxidation. In comparison with traditional physic-chemical method, XJ-2 could also achieve the same effectiveness. That is, XJ-2 showed metabolization ability of Disperse Blue 2BLN, which provided an effective way to treat effluent containing anthraquinone dyes.

Figure 5.

GC-MS spectras of Disperse Blue 2BLN's degraded products.

Figure 5.

(Continued)

Enzyme study

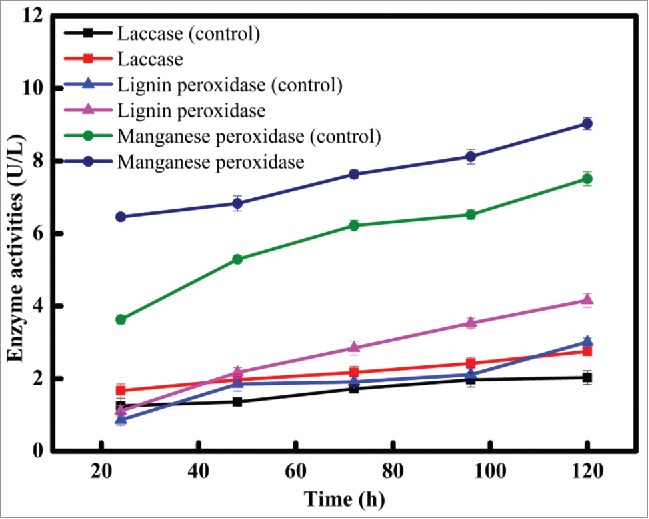

Generally dyes are cleaved with an active site available for enzymes to attack the molecule. The fungal decolorization was associated with involvement of its ligninolytic system with low substrate specificity, making it suitable for catalyze oxidation of phenolic compounds and recalcitrant pollutants. The decolorization mechanism of Disperse Blue 2BLN with XJ-2 was also estimated with the intracellular and extracellular ligninolytic enzymes activities. As can be seen from Fig. 6, XJ-2 could produce ligninolytic enzymes whether Disperse Blue 2BLN existing or not. However, XJ-2 showed higher enzyme activity in dye medium than control, which indicated that dye could positively induce the production of enzymes to a certain extent, although ligninolytic enzymes producing was the inherent characteristic of XJ-2.

Figure 6B.

The contrast of extracellular enzyme activities between experimental group (contained dye) and control group (without dye).

Figure 6A.

The contrast of intracellular enzyme activities between experimental group (contained dye) and control group (without dye).

Meanwhile, the interrelation between enzyme activities, biomass and decolorization rate was shown in Fig. 7. It was found that intracellular and extracellular activities of laccase, lignin peroxidase, and manganese peroxidase were all involved in the decolorization of Disperse Blue 2BLN with XJ-2. Among, slow increase in the intracellular activities of lignin peroxidase and manganese peroxidase were observed over period of decolorization. It was appeared that intracellular laccase might be contributed just little to decolorization when the other 2 intracellular peroxidases were put into consideration. Instead, extracellular manganese peroxidase activities clearly increased according to the increase of biomass and decolorization rate. Similarly, Ardag Akdogan et al. resulted that the enzymatic activities of laccase and manganese peroxidase gradually decreased during the process of biodecolorization of Remazol Brilliant Blue by 2 different organisms.31 Similiar with previous report, manganese peroxidase activities of XJ-2 showed the rise tendency along with the increase of biomass and decolorization rate in this work, which indicated the well detoxification to Disperse Blue 2BLN owned by XJ-2. Besides, Fu and Viraraghavan had reported that the relative contributions of manganese peroxidase, lignin peroxidase and laccase to the decolorization of dyes may vary among different species.34 Results obtained in this work indicated that manganese peroxidase of XJ-2 had prominent role in dye decolorization.

Figure 7B.

The correlation between extracellular enzyme activities, biomass and decolorization rate of Disperse Blue 2BLN.

Figure 7A.

The correlation between intracellular enzyme activities, biomass and decolorization rate of Disperse Blue 2BLN.

Degradation pathway analysis

There were reports on enzymes that catalyzed the reductive cleavage of anthraquinone rings during the biologic degradation of dyes.35 This cleavage process of anthraquinone ring can be easily achieved under the microaerophilic conditions. In this work, the manganese peroxidase, as the key component of extracellular ligninolytic enzymes of XJ-2, could catalyze the oxidation of Mn2+ into Mn3+ and further form Mn3+ chelates which caused one-electron oxidation of various compounds, suggested the non-specific reduction of Disperse Blue 2BLN. In addition, Xie et al. studied the degradation mechanism of Disperse Blue 2BLN from the order of band and proposed that the weaker the bond order, the more easily broken the bond, in which Disperse Blue 2BLN had 3 weaker bond order.36 Therefore, more than one degradation pathways of anthraquinone dye by XJ-2 were proposed (Fig. 8): The conjugate structure of Disperse Blue 2BLN were first attacked by manganese peroxidase produced by XJ-2, and then led to the breakage of dye chromogenic groups, which was the key step for decolorization of anthraquinone dyes. The intermediate A, B and D were produced then. In previous studies, ligninolytic enzymes of Phanerochaete chrysosporium had been proved to possess good catalytic oxidation ability to various substrates.37 It was strongly supported that intermediate A, B and D could further form lower molecular weight molecules C, E and F by oxidization decarboxylation, oxidization polymerization and hydroxylation. Furthermore, the compound G was formed via oxidization by enzymes. Finally, the compound G and F might take part in TCA cycle which underwent partial mineralization. Similarly, Yang et al. proposed that the degradation of malachite green catalyzed by manganese peroxidase secreted by Irpex lacteus F17 may via 2 different routes by either N-demethylation of malachite green or the oxidative cleavage of the C–C double bond in malachite green.38 Additionally, Yang et al. proposed that the mechanism of HOPDA catalyzed reaction by manganese peroxidase from a white rot fungus SQ01 was due to the fracture between Cα-Cβ, then release benzyl and finally form into aromatic acid.39 By comparison, degradation pathways of Disperse Blue 2BLN by XJ-2 were due to the breakage of anthraquinone chromophore at different positions, which they were C10-C11, C13-C14 (Ι) and C10-C11, C12-C13(П), respectively. Additionally, from the point of view of the relative content of metabolites, the compound of A had higher content in GC-MS comparing with the compound of B. Hence, the hypothesis of Disperse Blue 2BLN degradation pathway with XJ-2 tends to follow the former.

Figure 8.

Degradation pathways of Disperse Blue 2BLN.

Osma et al. proposed that the pathway for Remazol Brilliant Blue R degradation by immobilised laccase, but formed 2 sub-products owned higher molecular weights.28 Liu et al. reported that the degradation mechanisms of anthraquinone dye Alizarin Red by chloroperoxidase, but end product obtained also had higher molecular weights.26 Compared with previous literatures, the enzymatic degradation end products produced by XJ-2 had smaller molecular weights, even achieved partial mineralization. That made XJ-2 much meaningful to treat practical wastewater containing anthraquinone dyes. Additionally, it's acknowledged that intermediates produced by laccase easily repolymerized, which was unbeneficial for the dye decolorization. Fortunately, other ligninolytic enzymes were also involved in biodecolorization in this work making laccase products susceptible to ring cleavage, which attributed to further biodegradation even mineralization.

Conclusions

This work showed that XJ-2 had broad spectrum ability for degrading different anthraquinone dyes. Analysis of degradation intermediates by FTIR and GC-MS denoted the catabolism of the target dye and some intermediates were identified. Intracellular and extracellular enzyme activities experiments had strongly suggested the key role of manganese peroxidase in the decolourization process of target dye. At the same time, 2 feasible degraded pathways of target dye were first proposed based on identified metabolites and previous literatures, which ensured the ecofriendly degradation of target dye. All results indicated a potential application of strain XJ-2 in treatment of anthraquinone dyes wastewater.

Materials and methods

Dye and chemicals

Anthraquinone dyes were kindly provided by one textile company in Shihezi (Table 1). ABTS (2, 2′-azion-bis (3-ethyl-benzothiazoline)-6-sulphonic acid) was purchased from BIO BASIC INC (Canada). All the chemicals used in this work were analytical grade purity or above.

Table 1.

Chemical structure of anthraquinone dyes used in the study and their corresponding λmax.

| Anthraquinone dye | Formula | λmax(nm) | Chemical structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disperse Red 3B | C20H13NO4 | 332 |  |

| Disperse Blue 2BLN | C17H22N2O3 | 567 |  |

| Reactive Brilliant Blue | C22H16N2Na2O11S3 | 592 |  |

| Bromamine Acid | C14H8BrNO5S | 426 |  |

| Alizarin Green | C28H20N2Na2O8S2 | 620 |  |

| Mordant Red 3 | C17H7NaO7S | 530 |  |

Microorganism and culture media

XJ-2 was stored at China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center and the accession number was CGMCC12963. Czapek's medium was used for the culture of microorganism, which contained (g L−1): NaNO3 2, K2HPO4 1, KCl 0.5, MgSO4 0.5, FeSO4 0.01, sucrose 30. And dye medium was used for the examination of the decolorization ability of XJ-2, which contained Czapek's medium and 50 mg L−1 of anthraquinone dye.

Decolorization experiments

Under aseptic conditions, a 24 h culture of XJ-2 with 2% of inoculums was inoculated in 150 mL Erlenmeyer flask with 50 mL Czapek's medium and incubated at 35°C for 48 h with shaking, first. After activation, XJ-2 was inoculated in 150 mL Erlenmeyer flask with 50 mL dye medium and incubated at 175 rpm and 35°C. Aliquots (8 mL) of the culture were withdrawn at fixed time intervals (24 h) and centrifuged at 8161 g for 15 min.

Assays

Concentration of anthraquinone dyes in supernatants was monitored by UV-vis spectrophotometer (spectrumlab S22pc, China). The characteristic absorption wavelength (λmax) of the anthraquinone dyes used in this study was shown in Table 1. The decolorization rate was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where A0 and A1 represented the initial and final absorbance of the dye, respectively.29 All the decolorization experiments were performed in triplicate and the average values were used in calculations.

Infrared spectra of preprocessing liquid samples were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) (Magna-IR 750, Thermo Nicolet). KBr was used as the background; liquid samples were pointed at potassium bromide tableting to obtain their infrared spectra. The resolution and scan number were set at 8.0 cm−1 and 16 times, respectively. The scan range of the wave number was set at mid IR region (4000–400 cm−1).

To identify the intermetabolites during the degradation of Disperse Blue 2BLN by XJ-2, gas chromatography in combination with mass spectrometric detection (GC-MS) analysis were performed with an Agilent 7890A GC system coupled to an Agilent 5975C inert MSD with Triple-Axis Detector system (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA). GC analysis was performed with a HP5 capillary chromatographic column (320 µm × 0.25 µm × 30 m), the injection was conducted on a splitless mode, the temperature programmed mode according to Jen-Mao described previously.30 The injector temperature was maintained at 250°C and helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1.

Enzymatic activities

Enzyme activities both in intra and extracellular of XJ-2 were assayed by measuring the increase in optical density at suitable wavelengths with a spectrumlab S22pc spectrophotometer. Cell free supernatants were used to determine extracellular enzyme activities. Cells were broken by quickly grinding in liquid nitrogen and then dissolved in sodium acetate buffer (0.2 M, pH 5.0). The acquired supernatants by centrifuging at 8161 g for 15 min were used for intracellular enzyme samples.

Laccase activities were assayed by monitoring the initial rate of the increase in absorbance at 420 nm with intra and extracellular enzyme samples. The test cuvettes contained ABTS (0.5 mM), 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) and suitable amount of enzyme in a reaction mixture of 3 mL. Lignin peroxidase activity was determined in a reaction mixture of 3 mL containing veratryl alcohol (10 mM) in 125 mM sodium tartrate buffer (pH 5.0) and suitable amount of enzyme. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 2 mM H2O2 and monitored increase in optical density at 310 nm due to the oxidation of veratryl alcohol to veratrylaldehyde. Manganese peroxidase activity was determined in a reaction mixture of 3 mL containing MnSO4 (0.1 mM) in 100 mM sodium tartrate buffer (pH 5.0) and suitable amount of enzyme. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 0.1 mM H2O2 and measured increase in absorbance at 280 nm. All enzyme assays were performed at 35°C where reference blank contained all components except enzyme. One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to oxidize 1 µM substrate in 1 min.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the valuable comments from anonymous reviewers on this work.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21466032) and Scientific Research Foundation for Changjiang Scholars of Shihezi University (No. CJXZ201501).

References

- [1].Singh K, Arora S. Removal of synthetic textile dyes from wastewaters: A critical review on present treatment technologies. Crit Rev Env Sci Tec 2011; 41:807-878; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/10643380903218376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Epolito W, Lee Y, Bottomley L, Pavlostathis S. Characterization of the textile anthraquinone dye Reactive Blue 4. Dyes Pigments 2005; 67:35-46; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.dyepig.2004.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Deng D, Guo J, Zeng G, Sun G. Decolorization of anthraquinone, triphenylmethane and azo dyes by a new isolated Bacillus cereus strain DC11. Int Biodeter Biodegr 2008; 62:263-269; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ibiod.2008.01.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Novotny C, Dias N, Kapanen A, Malachova K, Vandrovcova M, Itavaara M, Lima N. Comparative use of bacterial, algal and protozoan tests to study toxicity of azo- and anthraquinone dyes. Chemosphere 2006; 63:1436-1442; PMID: 16297428; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Miranda Rde C, Gomes Ede B, Pereira N Jr, Marin-Morales MA, Machado KM, Gusmao NB. Biotreatment of textile effluent in static bioreactor by Curvularia lunata URM 6179 and Phanerochaete chrysosporium URM 6181. Bioresource Technol 2013; 142:361-367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.05.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Forgacs E, Cserhati T, Oros G. Removal of synthetic dyes from wastewaters: a review. Environ Int 2004; 30:953-971; PMID: 15196844; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.envint.2004.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ren S, Guo J, Zeng G, Sun G. Decolorization of triphenylmethane, azo, and anthraquinone dyes by a newly isolated Aeromonas hydrophila strain. Appl Microbiol Biot 2006; 72:1316-1321; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00253-006-0418-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eichlerova I, Homolka L, Benada O, Kofronova O, Hubalek T, Nerud F. Decolorization of Orange G and Remazol Brilliant Blue R by the white rot fungus Dichomitus squalens: toxicological evaluation and morphological study. Chemosphere 2007; 69:795-802; PMID: 17604080; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.04.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Park JB, Craggs RJ, Shilton AN. Wastewater treatment high rate algal ponds for biofuel production. Bioresource Technol 2011; 102:35-42; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tan L, Ning S, Zhang X, Shi S. Aerobic decolorization and degradation of azo dyes by growing cells of a newly isolated yeast Candida tropicalis TL-F1. Bioresource Technol 2013; 138:307-313; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ooi T, Shibata T, Sato R, Ohno H, Kinoshita S, Thuoc TL, Taguchi S. An azoreductase, aerobic NADH-dependent flavoprotein discovered from Bacillus sp.: functional expression and enzymatic characterization. Appl Microbiol Biot 2007; 75:377-386; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00253-006-0836-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mazumder R, Logan J, Mikell Jr A, Hooper S. Characteristics and purification of an oxygen insensitive azoreductase from Caulobacter subvibrioides strain C7-D. J Ind Microbiol Biot 1999; 23:476-483; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.jim.2900734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Blumel S, Stolz A. Cloning and characterization of the gene coding for the aerobic azoreductase from Pigmentiphaga kullae K24. Appl Microbiol Biot 2003; 62:186-190; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00253-003-1316-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Phugare SS, Kalyani DC, Patil AV, Jadhav JP. Textile dye degradation by bacterial consortium and subsequent toxicological analysis of dye and dye metabolites using cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and oxidative stress studies. J Hazard Mater 2011; 186:713-723; PMID: 21144656; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Muhammad T, Muhammad Z, Naseem R, Subhe S, Shoukat P. Biosorption characteristics of Aspergillus fumigatus for the decolorization of triphenylmethane dye acid violet 49. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014; 98:3133-3141; PMID: 24136473; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00253-013-5306-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Caglayan A, Ülküye D, Ö Kadir, Alev A. Degradation of Reactive Blue by the mixed culture of Aspergillus versicolor and Rhizopus arrhizus in membrane bioreactor (MBR) system. Desalin Water Treat 2014; 1-7. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sabrien A. Decolorization of Different Textile Dyes by Isolated Aspergillus niger. Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2016; 9:149-156; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3923/jest.2016.149.156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Andleeb S, Atiq N, Robson GD, Ahmed S. An investigation of anthraquinone dye biodegradation by immobilized Aspergillus flavus in fluidized bed bioreactor. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2012; 19:1728-1737; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11356-011-0687-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ali N, Hameed A, Ahmed S, Khan AG. Decolorization of structurally different textile dyes by Aspergillus niger SA1. World J Microb Biot 2007; 24:1067-1072; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11274-007-9577-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jin XC, Liu GQ, Xu ZH, Tao WY. Decolorization of a dye industry effluent by Aspergillus fumigatus XC6. Appl Microbiol Biot 2007; 74:239-243; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00253-006-0658-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang BE, Hu YY. Bioaccumulation versus adsorption of reactive dye by immobilized growing Aspergillus fumigatus beads. J Hazard Mater 2008; 157:1-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Solís M, Solís A, Pérez HI, Manjarrez N, Flores M. Microbial decolouration of azo dyes: A review. Process Biochem 2012; 47:1723-1748; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gomi N, Yoshida S, Matsumoto K, Okudomi M, Konno H, Hisabori T, Sugano Y. Degradation of the synthetic dye amaranth by the fungus Bjerkandera adusta Dec 1: inference of the degradation pathway from an analysis of decolorized products. Biodegradation 2011; 22:1239-1245; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10532-011-9478-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang H, Li Z. Three important enzymes for lignin degradation. Journal of Biology 2003; 20:9-11+33. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bellou S, Makri A, Sarris D, Michos K, Rentoumi P, Celik A, Papanikolaou S, Aggelis G. The olive mill wastewater as substrate for single cell oil production by Zygomycetes. J Biotechnol 2014; 170:50-59; PMID: 24316440; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liu L, Zhang J, Tan Y, Jiang Y, Hu M, Li S, Zhai Q. Rapid decolorization of anthraquinone and triphenylmethane dye using chloroperoxidase: Catalytic mechanism, analysis of products and degradation route. Chem Eng J 2014; 244:9-18; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cej.2014.01.063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kornillowicz-Kowalska T, Rybczynska K. Anthraquinone dyes decolorization capacity of anamorphic Bjerkandera adusta CCBAS 930 strain and its HRP-like negative mutants. World J Microb Biot 2014; 30:1725-1736; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11274-014-1595-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Osma JF, Toca-Herrera JL, Rodriguez-Couto S. Transformation pathway of Remazol Brilliant Blue R by immobilised laccase. Bioresour Technol 2010; 101:8509-8514; PMID: 20609582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ge Y, Wei B, Wang S, Guo Z, Xu X. Optimization of anthraquinone dyes decolorization conditions with response surface methodology by Aspergillus. Korean Chem Eng Res 2015; 53:327-332; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.9713/kcer.2015.53.3.327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fanchiang JM, Tseng DH. Degradation of anthraquinone dye C.I. Reactive Blue 19 in aqueous solution by ozonation. Chemosphere 2009; 77:214-221; PMID: 19683783; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ardag Akdogan H, Canpolat M. Comparison of Remazol Brillant Blue Removal from wastewater by two different organisms and analysis of metabolites by GC/MS. J Aoac Int 2014; 97:1416-1420; PMID: 25902993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5740/jaoacint.12-136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Parshetti GK, Telke AA, Kalyani DC, Govindwar SP. Decolorization and detoxification of sulfonated azo dye methyl orange by Kocuria rosea MTCC 1532. J Hazard Mater 2010; 176:503-509; PMID: 19969416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.11.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rajkumar D, Song BJ, Kim JG. Electrochemical degradation of Reactive Blue 19 in chloride medium for the treatment of textile dyeing wastewater with identification of intermediate compounds. Dyes Pigment 2007; 72:1-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.dyepig.2005.07.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fu Y, Viraraghavan T. Fungal decolorization of dye wastewaters: a review. Bioresour Technol 2001; 79:251-262; PMID: 11499579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00028-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sugano Y, Matsushima Y, Tsuchiya K, Aoki H, Hirai M, Shoda M. Degradation pathway of an anthraquinone dye catalyzed by a unique peroxidase DyP from Thanatephorus cucumeris Dec1. Biodegradation 2009; 20:433-440; PMID: 19009358; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10532-008-9234-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Xie J, Xiang Q, Feng Y, Fu J, Yang Q, Liu J. Study on decolorization of Disperse Blue 2BLN by chlorine dioxide. Chemical Research and Application 2001; 13:197-199. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sue HC, Seung-Hyeon M, Man BG. Biodegradation of chlorophenols using the cell-free culture broth of Phanerochaete chrysosporium immobilized in polyurethane foam. J Chem Technol Biot 2000; 77:999-1004. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yang X, Zheng J, Lu Y, Jia R. Degradation and detoxification of the triphenylmethane dye malachite green catalyzed by crude manganese peroxidase from Irpex lacteus F17. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2016; 1-13; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yang X, Zhang X. Transformation of biphenyl intermediate metabolite by manganese peroxidase from a white rot fungus SQ01. Acta Microbiologica Sinica 2016; 56:1044-1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]