Abstract

Interest in using Bayesian methods for estimating item response theory models has grown at a remarkable rate in recent years. This attentiveness to Bayesian estimation has also inspired a growth in available software such as WinBUGS, R packages, BMIRT, MPLUS, and SAS PROC MCMC. This article intends to provide an accessible overview of Bayesian methods in the context of item response theory to serve as a useful guide for practitioners in estimating and interpreting item response theory (IRT) models. Included is a description of the estimation procedure used by SAS PROC MCMC. Syntax is provided for estimation of both dichotomous and polytomous IRT models, as well as a discussion on how to extend the syntax to accommodate more complex IRT models.

Keywords: Markov chain Monte Carlo, item response theory, software

Introduction

The previous 20 years have witnessed a proliferation of studies using Bayesian methods in statistical research and publications. In fact, topics related to Bayesian methods now represent approximately 20% of published articles in statistics (Andrews & Baguley, 2013). This trend toward increasing numbers of Bayesian articles has also been witnessed in educational research, and, more specifically, item response theory (IRT) modeling. A brief overview of the number and types of applications in IRT using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) in the past 5 years (2009-2013) is provided in Table 1. MCMC methodology has been applied in the IRT framework to dichotomous models (e.g., two-parameter logistic; Saito, Iwata, Kawakame, Matsuyama, & World Mental Health Japan 2002-2003 collaborators, 2010), polytomous models (e.g., graded response model; Baldwin, Bernstein, & Wainer, 2009), and more complex models such as the cognitive diagnostic assessment fusion model (Jang, 2009), mixture Rasch with response time (Meyer, 2010), and logistic positive exponent (Bolfarine & Bazan, 2010), among others.

Table 1.

Applications of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for Item Response Theory (IRT) From 2009 to 2013.

| Author | Yr | Journal | Model | I | N | Software | Burn-in | Iteration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin | 2009 | Statistics in Medicine | Graded response model | 20 | 12 | SCORIGHT | 165,000 | 20,000 |

| Bolfarine | 2010 | Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics | Logistic positive exponent | 18 | 974 | WinBUGS | ||

| Choo | 2013 | Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation | Mixture Rasch model | 18 | 2,156 | WinBUGS | ||

| Curi | 2011 | Statistical Methods in Medical Research | IRT for embarrassing items | 20 | 348 | WinBUGS | ||

| De Gooijer | 2011 | Computational Statistics and Data Analysis | Two-parameter logistic (2PL) | 6 | 25-200 | |||

| de la Torre | 2009b | Applied Psychological Measurement | MIRT with ancillary information | 77 | 1,500 | Ox | 5,000 | 20,000 |

| de la Torre | 2009 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Higher-order IRT | 90 | 2,255 | Ox | 3,000 | 15,000 |

| de la Torre | 2010 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Higher-order IRT | 90 | 2,255 | Ox | 1,000 | 10,000 |

| de la Torre | 2009 | Applied Psychological Measurement | IRT subscoring methods | 90 | 2,255 | Ox | 2,000 | 10,000 |

| de la Torre | 2009a | Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics | Deterministic-input noisy-AND (DINA) model | 15 | 2,144 | Ox | ||

| Edwards | 2010 | Psychometrika | Confirmatory item analysis | 102 | 3,000 | |||

| Entink | 2011 | Statistics in Medicine | Mixture multilevel IRT with survival model | 30 | 668 | BOA R package | 5,000 | 10,000 |

| Entink | 2009 | Psychometrika | Multivariate multilevel IRT | 22, 65 | 286, 388 | R | 10,000, 10,000 | 5,000, 20,000 |

| Finke | 2009 | Journal of Theoretical Politics | Two-parameter logistic (2PL) | 61 | 82 | GAUSS | 10,000 | 15,000 |

| Fragoso | 2013 | Biometrical Journal | Non-compensatory and compensatory MIRT two-parameter | 21 | 1,111 | 5,000 | 100,000 | |

| Fu | 2009 | Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation | Multidimensional three-parameter logistic (3PL) | 6 | 36 | MATLAB | 1,000 | 15,000 |

| Fukuhara | 2011 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Bifactor MIRT for testlets | 45 | 2,000 | WinBUGS | 7,000 | 15,000 |

| Geerlings | 2011 | Psychometrika | Hierarchical IRT for items in families | 33 (11 families) | 1,350 | 20,000 | 100,000 | |

| Henson | 2009 | Psychometrika | Log-linear cognitive diagnosis | 12 | 2,144 | MPLUS | 5,000 | 10,000 |

| Hsieh | 2010 | Multivariate Behavioral Research | Generalized linear latent and mixed model | 13 | 838 | WinBUGS 1.4.3 | 4,000 | 12,000 |

| Huang | 2013 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Hierarchical IRT | 247, 76 | 5,000, 987 | WinBUGS | 1,000 | 9,000 |

| Hung | 2011 | Multivariate Behavioral Research | Random-situation random-weight model with internal restrictions on item difficulty (MIRID) | 10 | 268 | WinBUGS | 1,000 | 4,000 |

| Hung | 2010 | Multivariate Behavioral Research | Multigroup multilevel categorical latent growth curve | 7 | 264 | WinBUGS | 5,000 | 10,000 |

| Hung | 2012 | Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics | Generalized multilevel facets model for longitudinal data | 5 | 238 | WinBUGS | 8,000 | 4,000 |

| Jang | 2009 | Language Testing | Fusion model (CDA) | 37 | 2,703 | Arpeggio | 13,000 | 30,000 |

| Jiao | 2013 | Journal of Educational Measurement | One-parameter logistic (1PL) testlet | 54 | Winbugs | 1,000 | 2,000 | |

| Jiao | 2012 | Journal of Educational Measurement | Multilevel testlet | 32 | 1,644 | WinBUGS | 2,000 | 3,000 |

| Kang | 2009 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Polytomous models (focus on model selection indices) | 5 | 3,000 | WinBUGS | 5,000 | 6,000 |

| Kieftenbeld | 2012 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Graded response model | |||||

| Kim | 2009 | Communications in Statistics | SEM for ordinal response data with missingness | 25 | 70,548 | FORTRAN | 1,000 | 10,000 |

| Li | 2012 | Statistics in Medicine | Generalized Partial Credit Model | 5 | 500 | 2,000 | 152,000 | |

| Li | 2009 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Mixture IRT | 48 | 1,200 | WinBUGS | 3,000 | 10,000 |

| Luo | 2013 | Statistics in Medicine | Multilevel IRT | 32 | 361 | OpenBUGS 3.2.2 | 45,000 | 50,000 |

| Meyer | 2010 | Applied Psychological Measurement | Mixture Rasch with response time | 60 | 524 | OpenBUGS 3.0.3 | 39,999 | 30,001 |

| Saito | 2010 | International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research | Two-parameter logistic (2PL) | 14 | 353 | SAS/IML Version 9.1 (Gibbs) | 1,000 | 10,000 |

| Santos | 2013 | Journal of Applied Statistics | Skew multiple group IRT | 20-80 | 295-568 | Ox | ||

| Soares | 2009 | Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics | Integrated Bayesian for DIF | 56 | 7,998 | MATLAB | ||

| Stone | 2009 | Applied Measurement in Education | Multidimensional IRT | 59 | 10,545 | WinBUGS | ||

| Tao | 2013 | Japanese Psychological Research | Two-parameter logistic testlet with testlet-level discrimination | 28 | 1,289 | 5,000 | 30,000 | |

| Usami | 2011 | Japanese Psychological Research | Generalized graded unfolding model | 20 | 313 | R | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| van den Hout | 2010 | Journal of the Royal Statistical Society | Randomized response | 3 | 2,227 | WinBUGS | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| Wang | 2010 | Statistics in Medicine | Testlet with covariates | 21 | 718 | 10,000 | 20,000 | |

| Yao | 2010 | Journal of Educational Measurement | MIRT, bifactor | 217 | 3,953 | BMIRT |

Note. Author represents first author only, Yr is the year of publication, Journal is the journal in which the study was published, Model is a brief description of the model estimated under the MCMC framework, I refers to number of items, N refers to number of respondents/subjects, Software is the software program implementing the MCMC algorithm, Burn-in is the number of burn-in iterations, and Iteration is the number of MCMC samples drawn after the burn-in period.

Software for implementation of Bayesian estimation methods for IRT has also garnered attention. Specifically, software to implement Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation has been described and illustrated in several sources. For instance, Curtis (2010) provided BUGS (Lunn, Thomas, Best, & Spiegelhalter, 2000) syntax for common IRT models. Several (nstudies = 17) of the applications in Table 1 rely on BUGS software for conducting the MCMC analysis. The BUGS software has several benefits, one of which is its open source nature. Another advantage is that the modeling language is quite flexible, allowing for a comprehensive set of models to be estimated rather than the practitioner having to choose from a prespecified selection of models. Additionally, BUGS derives the required MCMC elements (i.e., the full conditional distributions for Gibbs sampling; Lynch, 2007) rather than requiring the practitioner to do the derivations on their own.

Despite the advantages of using BUGS, there are some drawbacks. First, problems in model convergence are hard to diagnose and rectify. In addition, mistakes in BUGS syntax can be difficult to identify (Li & Baser, 2012). A second, but related, disadvantage is that Curtis’ syntax assumes a working knowledge of the BUGS language (Curtis, 2010), which may not be the case for those practicing or studying psychometrics. Third, BUGS has memory limitations that may make storing important information about the estimation difficult or impossible.

Another option for MCMC estimation is the R (R Development Core Team, 2010) package R2WinBugs (Gelman, 2013), which is used in conjunction with BUGS. Li and Baser (2012) provide a detailed explanation of how to perform MCMC estimation using R2WinBUGS for estimation of IRT models. Their option requires two syntax files—one in R and one in BUGS—and two software programs. This could be an inefficient approach when other options require just one program and one syntax file. Additionally, the problem with diagnosing and rectifying BUGS errors still exists. These complications may have led to the developer of the R2WinBUGS package (Gleman, 2013) recommending use of Stan (Stan Development Team, 2014) instead of WinBUGS for MCMC estimation. As yet, the models in Li and Baser (2012) and Curtis (2010) have not been replicated in Stan in a published source.

Working solely in the R language, the package MCMCPack (Martin, Quinn, & Park, 2011) is another choice for MCMC estimation. When using MCMCPack, the modeler is limited to a smaller set of models, as the package contains a set of 18 prespecified models. As with the BUGS software, both R2WinBUGS and MCMCPack have memory limitations that prevent complete information about the estimation procedure from being stored for future use (Martin et al., 2011). There is the option to store information on item and person parameters, but the documentation on MCMCPack explicitly states this should only be done if the chain is thinned heavily, or for applications with small numbers of individuals and items (Martin et al., 2011). Storing the information and using it in posterior analysis is typically vital for model checking procedures such as posterior predictive checks, prior sensitivity, and fully describing the posterior distribution. Two other choices include BMIRT (Yao, 2003) and MPLUS (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2011).

A less-frequently used alternative for MCMC estimation of IRT models is a general purpose procedure developed by SAS, PROC MCMC (SAS Institute Inc., 2014). The SAS MCMC procedure avoids some of the memory limitations encountered when using R packages and allows for estimation of any model the practitioner is considering, similar to the advantages of BUGS and Stan. An additional benefit of PROC MCMC is in the timing. We implemented the generalized partial credit model (GPCM) example from Li and Baser (2012) in both SAS PROC MCMC and in R2WinBugs on an Intel Core i5-2540M CPU 2.60 GHz with 7.89 GB RAM useable memory. Li and Baser’s example contained 5 polytomously scored items, with five response categories per item, and 500 respondents. The timing varied considerably, with SAS PROC MCMC finishing in 4.92 minutes and R2Winbugs finishing in 299.08 minutes (4.98 hours). The timing in R2Winbugs was confirmed with Li (personal communication, May 7, 2014).

A comparison of the GPCM item parameter estimates from SAS PROC MCMC, R2WinBUGS, and two software programs implementing marginal maximum likelihood (MML) is found in Figure 1. The mean values from posteriors estimated in SAS PROC MCMC and R2WinBUGS were used as estimates for comparison to the MML estimates. Figure 1 illustrates that the parameter estimates among SAS PROC MCMC, R2Winbugs, R package ltm (MML implementation), and IRTPRO (MML implementation) are all quite similar. The efficiency and speed of the SAS procedure do not appear to be tradeoffs for the plausibility of the MCMC estimates.

Figure 1.

Estimated parameter comparisons.

It becomes clear that SAS PROC MCMC possesses many of the benefits of other software solutions, but offers the added advantage of vastly improved timing. The purpose of this article is to provide SAS PROC MCMC syntax to fit several IRT models in the Bayesian framework and to clearly describe the algorithms underlying the procedures. The article begins with a brief description of IRT models, both dichotomous and polytomous, and moves on to a description of the Metropolis–Hastings (MH) algorithm for MCMC estimation in the subsequent section. Then, a description of SAS PROC MCMC syntax is provided, followed by instructions on extending the basic examples to more complex models, such as those found in Table 1.

Item Response Theory Models

To facilitate discussion of IRT models, some general notation and terminology will be introduced first. Let i represent the item of interest (i = 1, 2, . . ., I items) and let n represent the examinee (n = 1, 2, . . ., N examinees). The latent ability trait of interest will be denoted by θ. Item responses will be denoted by x, with the nth examinee’s response to the ith item being xni.

Dichotomous Models

The three-parameter logistic (3PL; Birnbaum, 1968) is a general model for dichotomous responses. The probability of correct response by the nth person to the ith item, given their ability and item characteristics, for the 3PL is represented by the statistical IRT model

Other dichotomous models can be represented as constrained versions of the 3PL.

Polytomous Models

Much like dichotomous models, polytomous IRT models have item characteristics (e.g., discrimination and difficulty) and examinee latent traits (θ). For polytomous items, responses are scored xni = (0, 1, . . .mi), where mi represents the highest possible response category of the ith item. One example of a polytomous model is the generalized partial credit model (GPCM; Muraki, 1992). The probability of an examinee responding in response category k under the GPCM is defined by

The graded response model (Samejima, 1969) is another frequently used polytomous model, defined by

where

Other polytomous IRT models include the rating scale model (Andrich, 1978), nominal response model (Bock, 1972), and the sequential response model (Tutz, 1990).

Markov Chain Monte Carlo Estimation

Overview of Bayesian Statistics

Estimating the parameters in the dichotomous and polytomous IRT models discussed in Equations (1) to (4) can be accomplished in frequentist, Bayesian, or nonparametric frameworks. There is a continuing debate about the use of frequentist estimation versus Bayesian estimation (Casella & Berger, 1987; Sinharay, 2005). As with Sinharay (2005), this article will not attempt to serve as arbitrator to this debate, focusing instead on the use of SAS PROC MCMC as a tool in the application of MCMC estimation. What follows is a description of the Bayesian estimation toolkit, focusing specifically on the MH algorithm MCMC procedure.

All statistical probability models describe a mechanism, or relationship, which has generated the observed data (i.e., item response data), as a function of unobserved parameters (i.e., item parameters). However, information about the item parameters is not completely known, which introduces uncertainty into the relationship between the item response data and the item parameters. Treatment of this uncertainty is a fundamental difference between Bayesian and frequentist methods. In the Bayesian paradigm, parameters are treated as random variables (i.e., incorporate the uncertainty) and an entire distribution of possible parameter values is estimated. Conversely, frequentist methods treat parameters as fixed, but unknown, quantities.

In the Bayesian approach, two modeling stages are recognized. The first stage is specification of parameter uncertainty before any data are observed. This specification is termed the prior information because it represents information about the parameter before observing any data. Prior beliefs could come from other observed data and research, or represent expert opinions from the field (Fox, 2010). The second stage is specification of a model for observed data. This model represents the observed data as a function of unknown parameters, often termed the likelihood. That is, the likelihood is an indicator of how likely the practitioner is to observe the data under certain parameter specifications.

After the data are observed, prior information on the parameters is combined with information from the data (i.e., the likelihood) to provide a distribution of parameter information. Because this combination occurs after the data are observed, the distribution of potential parameter values is known as the posterior parameter distribution (Fox, 2010). The posterior distribution specifies the chance that each parameter equals a particular value or lies in a certain range of values. An example of a posterior can be found in the lower right panel of Figure 3. The majority of the distribution falls between −0.4 and −0.2 and we could say, with some confidence, that the item parameter is somewhere in that range. There is a much smaller chance that the parameter comes from the tails of the distribution, offering little confidence in a claim that the parameter equals −0.60.

Figure 3.

Diagnostic plots.

The central issue of Bayesian parameter estimation becomes estimating the posterior distribution. To introduce some notation, assume the observed item response data, x, are used to measure some item parameter, b, representing item difficulty. To represent the prior information we have about b, f(b) is used. Information about the likelihood of x as a function of the parameters is denoted by f(x|b). However, what practitioners are often most interested in is the posterior of b, f(b|x), representing the distribution of the parameter given the prior beliefs and the observed data. The prior, likelihood, and posterior are related to one another via Bayes’s theorem:

Markov Chain Monte Carlo Estimation

Estimating the left-hand side of Equation (5), the posterior, is often not directly possible because of analytical complexity. Thus, the issue of posterior distribution construction must be addressed. A general purpose method, MCMC, is used for the task of constructing the posterior when the analytical complexity becomes too great for direct computation. MCMC is a method of sampling, relying on the Monte Carlo principle that anything a practitioner wishes to know about a random variable (e.g., b) can be learned by sampling many times from the probability distribution of b (Jackman, 2009). If the practitioner wishes to learn about the posterior of b, they must sample many times from the posterior of b. But, how does one sample from a distribution if that is what they are attempting to estimate? If the posterior is a common distribution (e.g., normal), sampling from the posterior is relatively simple because it has a known form. However, consider the posterior distribution in Figure 3. The posterior does not have a common distributional form and MCMC is needed in order to learn about the posterior.

To sample from an unknown distributional form, a Markov chain is used, which is a sequence of random variables. The sequence has a particular property: The random variable at the current time depends only on its immediate predecessor. Letting the difficulty parameter b represent the random variable, then the value of b in time t of the sequence depends only on the value of b in time t-1. Once constructed, the Markov chain represents the posterior distribution and each point in the chain represents a sample of the posterior.

The Metropolis–Hastings (MH; Hastings, 1970; Metropolis, Rosenbluth, Rosenbluth, Teller, & Teller, 1953; Metropolis & Ulam, 1949) algorithm is one method for creating the Markov chain sequence. This article focuses on the MH algorithm because SAS PROC MCMC implements the random walk MH algorithm. The chain starts with a beginning value of the parameter, bstart. This start value can be a completely random value, or it can be a value specified by the practitioner to represent a belief about the parameter. The algorithm transitions to the next value of the parameter (i.e., the next element of the chain), bnext, using the following general steps for this algorithm:

Begin with bnext, a candidate value for the Markov chain, drawn from a proposal distribution. A popular proposal distribution is the “random walk” proposal. That is, a value is randomly sampled from somewhere near the current point (bnext= bstart+ random error). The proposal distribution can change over iterations, a process referred to as tuning.

Compute an acceptance ratio, r, which represents the plausibility of the candidate value, bnext. The acceptance ratio ranges from 0 to 1 and represents how likely the candidate value is to have come from the posterior. Low acceptance ratios indicate the candidate value is not likely to have come from the posterior. High acceptance ratios indicate the candidate value is quite likely to have come from the posterior.

If r > 1, move to the candidate value, bnext. Otherwise, move to the candidate value with probability, r, and remain at the existing value, bstart, with probability 1 −r.

Repeat a specified number of times. The exact number of repetitions is specified by the practitioner. With each repetition of the algorithm, or iteration, the starting value is either the previous iteration’s accepted candidate or the previous iteration’s starting value. Once enough iterations have been completed, the sequence represents values of the posterior distribution and the information can be summarized.

An illustration of the random walk MH process is provided in Figure 2, assuming a standard normal distribution around the candidate points. Random sampling is employed from this proposal and the final Markov chain representing the posterior would be denoted by bstart, b1, b2, . . ., bfinal.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the random walk Metropolis–Hasting algorithm.

For those new to MCMC and the MH algorithm, a concrete example may prove a useful aid in understanding the MH algorithm incorporated in SAS PROC MCMC. The algorithm starts at an arbitrary point, say −2. If the acceptance ratio is high enough, the algorithm moves to the candidate value, bnext = −1.8. The chain would then contain two values: −2 and −1.8. Otherwise, the algorithm remains at the starting value, bstart = −2 and the chain has only one value: −2. This process is repeated over and over until a large number of repetitions has been reached.

Depending on the starting value, the first several elements of the chain are typically not very good representations of the parameter and are thrown away. These throw-away elements are called the burn-in. As the algorithm continues through the parameter space, the algorithm will narrow in on one general location, the central mass of the distribution. Information about each instance of the algorithm, which provides information about the posterior, is saved. Our goal was only to provide those new to MCMC and the MH algorithm with a general overview. For a more technical and detailed description of MCMC for IRT, see Patz and Junker (1999) and Kim and Bolt (2007).

The previous discussion on MH relied on a unidimensional parameterization. However, extension of the MH algorithm to a higher-dimensional parameter space is straightforward. Let the k-dimensional parameter vector be represented by . An initial start value for each is chosen and a multivariate version of the random walk proposal distribution, such as a multivariate normal distribution, is used to select a k-dimensional new parameter. Other steps remain the same as those previously described. Chib and Greenberg (1995) provide a tutorial on the algorithm for multiple dimensions.

A special case of the random walk MH algorithm, described above, is the independence sampler (IS). The IS is so termed because new, proposed values for the Markov chain are entirely independent of the previous value in the chain. Essentially, the proposal distribution in the algorithm does not depend on the current point, as it does with the random walk MH algorithm. The IS still results in a Markov chain despite this independence property (SAS Institute Inc., 2014). In Figure 2, instead of the proposal centered over the current point, as in the random walk, the proposal may be uniform (i.e., flat) with the IS. Therefore, a value drawn from this flat distribution is independent of the current point.

With some models the practitioner may experience slow convergence of the Markov chain, meaning that the Markov chain slowly traverses the parameter space. This can happen, for example, when parameters are highly correlated with each other. If parameters are highly correlated, the chain will have high dependence, also referred to as high sample autocorrelation. The presence of autocorrelation can result in biased Monte Carlo standard errors. One common strategy to handle the biased standard errors is to thin the Markov chain in order to reduce sample autocorrelations (SAS Institute Inc., 2014). Thinning the chain implies keeping every tth simulated draw from each parameter chain and discarding the remaining draws. For example, if 10,000 iterations are used, keeping each 10th draw results in 1,000 draws retained and 9,000 draws discarded. This is an acceptable strategy as long as the chain converges. It is important to note that thinning a Markov chain can be wasteful because it throws away a proportion () of all the posterior samples generated. Additionally, MacEachern and Berliner (1994) found more precise posterior estimates if the entire Markov chain is used.

Syntax Samples

This section describes how the MH algorithm described above can be implemented in SAS PROC MCMC, which fits a wide range of models using Bayesian methods. To use the procedure, the user needs to specify a likelihood function for the data, start values for the parameters, and a prior distribution for the parameters. SAS PROC MCMC then obtains samples from the corresponding posterior distributions, produces summary and diagnostic statistics, and saves the posterior samples in an output data set that can be used for further analysis.

The default algorithm that PROC MCMC uses is an adaptive blocked random walk MH algorithm, described in the previous section, which uses a normal proposal distribution. In a multivariate parameter model, such as an IRT model, blocking parameters implies that if all parameters are proposed with one joint distribution, acceptance or rejection occurs for all parameters in the block. This can be rather inefficient, especially when parameters have vastly different scales. Allocating parameters into smaller, more homogeneous blocks, which are then updated separately, can avoid the inefficiencies. For example, one block could consist of all the discrimination parameters, another of all difficulty parameters, and a third block for all guessing parameters in a 3PL model. In SAS PROC MCMC, parameters may be blocked however the user sees fit, or specified without blocking.

To explain the SAS PROC MCMC syntax, a simple example will be provided for the 1PL model. The Law School Admission Test, Section VI (LSAT6), is used for illustrative purposes. This data set contains five items, each scored dichotomously, with the variables labeled x1 to x5. The data format required for use of SAS PROC MCMC is to have one row per person and one column per item. Using PROC MCMC for IRT also requires an identifier for each person, which can be created easily using data step syntax, as shown below:

data LSAT6; set LSAT6;

person = _N_;

run;

There are now six variables in the LSAT6 data set, labeled x1 to x5 and person.

Syntax for the 1PL model is provided in Listing 1. Line 1 asks for output delivery system graphics, which produces a new SAS data set, in this case, the posterior distribution, from an output object. The output delivery system graphics are then closed in Line 14. These are general commands and not specific to the IRT model or data set; what lies between these (Lines 2 to 12) represent specifics to the estimation at hand.

Listing 1.

One-Parameter Logistic Item Response Theory Model.

The second line invokes the MCMC procedure in SAS. The practitioner then goes on to specify the data set to be used (here, data = LSAT6) and whether to save the posterior samples. In this case, we have chosen to save the posterior samples data set and call it LSATPOST. Ten thousand iterations (nmc = 10,000), with a burn-in of 1000 (nbi = 1,000), will be generated. Of these 10,000 iterations, every fifth will be saved (thin = 5) in LSATPOST for a final posterior sample of 2,000. Finally, the monitor statement of line 2 dictates that SAS will compute convergence statistics for the a parameter and all five bi parameters, and produce a set of diagnostic graphics for those parameters. An example of these diagnostic plots can be found in Figure 3. The practitioner must to determine the number of burn-ins, required iterations, and if (and, consequently, how much) to thin for each model estimated. A useful discussion on convergence and the necessary number of iterations to achieve convergence can be found in Lynch (2007, pp. 131-153). Table 1 also provides the number of burn-in iterations and total iterations after burn-in to form the posterior. While these cannot be interpreted as hard and fast rules for the required values to achieve convergence, they may serve as a useful guideline for where to begin when estimating IRT models via MCMC.

The third line sets up arrays which allow for easy reference to parameters and variables. Essentially, these statements tell SAS that there are five objects called b and five objects called x. Use of arrays allows for looping other programming statements and makes the syntax more efficient. Colons in Listing 1 (e.g., b: ) indicate that anything starting with b follows the same set of commands. In Line 4, these colons translate to all difficulty parameters being given a start value of 0. Line 4 assigns start values to the parameters as well as the blocking structure. In this case, the a parameter is in one parameter block and all five of the bi parameters are grouped in a separate parameter block. Thus, if one bi parameter is rejected in an iteration, all bi parameters will be rejected when blocked in this manner.

All of the items are quite easy, with the majority of respondents answering all five items correctly. This information is reflected in assigning a prior distribution with a negative mean for all items, found in Line 5. Prior information on the parameters was assigned via: and . SAS PROC MCMC allows for a number of commonly used distributions such as the normal, lognormal, and uniform, but also possesses the ability for the user to specify their own distributional form for both the priors and final likelihood model. Person parameters are addressed via the random statement, line 6, with prior information of .

Lines 7 through 12 of Listing 1 describe the likelihood function for the 1PL model. Dichotomous models have the following log-likelihood function

where Pni1 represents the model to be estimated using MCMC methods, in this case, the 1PL. Line 7 is set to llike = 0; and this format is required for use because Equation (6) is a joint likelihood and we are accumulating log-likelihood values from all five items, x1 to x5. Line 8 specifies this accumulation, line 9 defines the specific IRT model, and line 10 represents the log-likelihood in Equation (6). Line 11 closes the loop (accumulation of log-likelihoods for the items) and line 12 tells SAS, via the general model statement, that we have specified our own distributional form that does not follow one of the standard SAS distributions.

After running the syntax in Listing 1, summary statistics from the posterior distributions can be used to describe the posterior. These summaries are found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Posterior Summary Statistics LSAT6, 1PL.

| Percentiles |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | M | SD | 25th | 50th | 75th |

| a | 0.7810 | 0.0638 | 0.7372 | 0.7795 | 0.8214 |

| b 1 | −3.4912 | 0.2820 | −3.6714 | −3.4640 | −3.2945 |

| b 2 | −1.2929 | 0.1370 | −1.3842 | −1.2869 | −1.1938 |

| b 3 | −0.3134 | 0.0992 | −0.3791 | −0.3116 | −0.2437 |

| b 4 | −1.6931 | 0.1495 | −1.7874 | −1.6882 | −1.5899 |

| b 5 | −2.7041 | 0.2152 | −2.8426 | −2.6927 | −2.5590 |

Note. M represents the posterior mean and SD is the posterior standard deviation. LSAT6 = Law School Admission Test, Section VI; 1PL = one-parameter logistic.

Conclusions, Future Directions

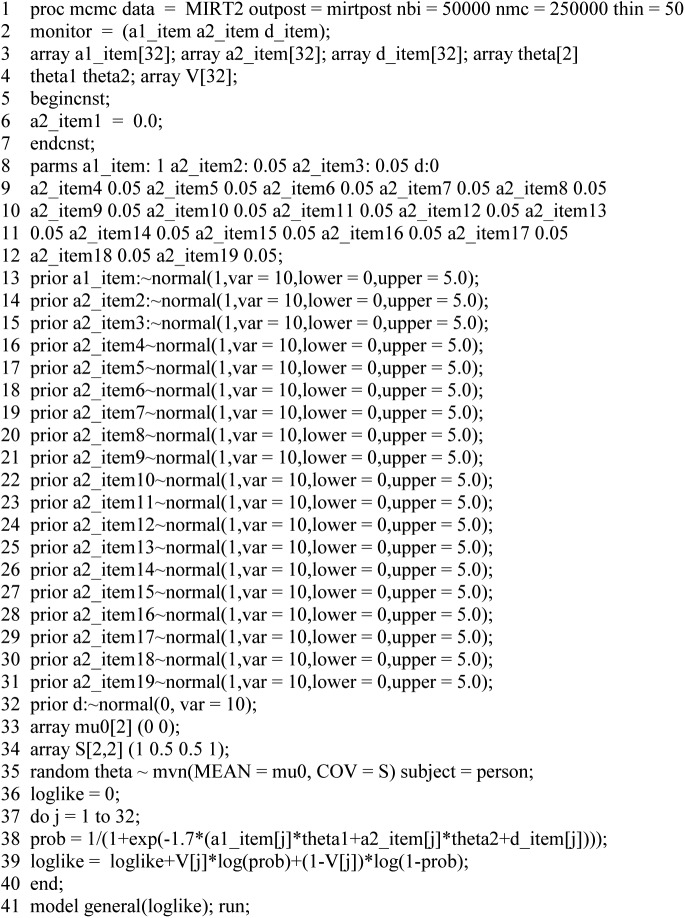

This article has provided a tutorial on the MH algorithm for MCMC estimation of IRT models as well as SAS syntax to estimate a common IRT model, the 1PL, using MCMC methods. Listings 2 and 3 provide syntax for the 2PL and 3PL, respectively. Polytomous models (GPCM and GRM) are found in Listings 4 and 5. While the models in Listings 1 through 5 are not representative of some of the most complex models found in Table 1, the syntax is quite simple to modify by changing the likelihood specification to meet the model of interest. For instance, if a multidimensional IRT (MIRT) model is being estimated by practitioners, SAS PROC MCMC allows for a multivariate distribution in the random statement, accommodating multiple correlated latent abilities, and, therefore, a multidimensional likelihood function. A two-dimensional compensatory MIRT model is represented by

Listing 2.

Two-Parameter Logistic Item Response Theory Model.

Listing 3.

Three-Parameter Logistic Item Response Theory Model.

Listing 4.

Generalized Partial Credit Item Response Theory Model, Replicating Li and Baser (2012).

Listing 5.

Graded Response Item Response Theory Model.

Listing 6 provides an example of how to estimate the MIRT model in Equation (7), where . Figure 4 provides a comparison of the generating item parameters and those estimated using NoHarm (Fraser, 1998) and the posterior means obtained from PROC MCMC. By default, NoHarm fixes the parameter a2 to zero for the first item. Thus, for comparability of parameters, we show how to fix the same a2 parameter in SAS PROC MCMC using the begincnst and endcnst set of statements (Line 5). We have also provided an example of incorporating hyperpriors (i.e., Listing 4).

Listing 6.

MIRT Model.

Figure 4.

Multidimensional item response theory model parameter recovery.

Several advantages were discussed for PROC MCMC, one of which is the speed of the procedure. Typical MCMC simulation studies have very few replications in comparison to frequentist simulation studies, partly because of the lengthy time to run of MCMC procedures. One recent development in SAS could help change this and allow for more rigorous simulation studies and a wider adoption of MCMC methodologies in general. The use of threaded technology in Enterprise Miner Version 13.1 (SAS Institute Inc., 2013) can substantially improve the timing of MCMC methods. The same model as Li and Baser (2012) finished in 63.29 seconds when employed on Enterprise Miner Version 13.1 using eight threads. We acknowledge all practitioners and students will not have access to Enterprise Miner Version 13.1, but for those heavily relying on Bayesian methods, this is an important option to consider.

SAS PROC MCMC is not without its limitations, however. SAS is not an open source product and, therefore, not freely available to all users. One solution to the cost is SAS OnDemand for Academics (SAS Institute Inc., 2012), a web-based version of SAS freely available to students and instructors. We did not test the use of the PROC MCMC in this version, however.

Another drawback is that only the MH algorithm is implemented in SAS PROC MCMC. In contrast, BUGS implements Gibbs sampling. However, there are several instances in which the MH algorithm is preferred to Gibbs sampling. First, there are cases in which a conditional distribution cannot be derived or determined from the joint density. A second, more common instance, is if a conditional density is not of a known form, inversion sampling is impossible, or it is difficult to find an appropriate envelope for rejection sampling. Third, Gibbs sampling may be inefficient for the model and data under consideration by the practitioner (Lynch, 2007). In generic programming languages such as R, C, or C++ the practitioner is limited only by their programming abilities as to which algorithm they use.

Despite these limitations, SAS PROC MCMC has proven to be a valuable tool for Bayesian estimation methods and this paper has provided the syntax to enable practitioners to estimate the IRT models of their choice. An added benefit of this article has been to provide readers with examples of MCMC applications over the past five years. Including the number of items, model types, sample size, burn-ins, and iterations can provide practitioners with rough guidelines when beginning implementation of their own MCMC applications. However, these values in Table 1 are not meant to be hard limits, but guiding suggestions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

*References marked with an asterisk indicate that the references are found in Table 1 and may not have specifically been cited in the body of the text.

- Andrews M., Baguley T. (2013). Prior approval: The growth of Bayesian methods in psychology. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 66, 1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrich D. (1978). A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika, 43, 561-573. [Google Scholar]

- *Baldwin P., Bernstein J., Wainer H. (2009). Hip psychometrics. Statistics in Medicine, 28, 2277-2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock R. D. (1972). Estimating item parameters and latent ability when responses are scored in two or more nominal categories. Psychometrika, 37, 29-51. [Google Scholar]

- *Bolfarine H., Bazan J. (2010). Bayesian estimation of the logistic positive exponent IRT model. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 35, 693-713. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum A. (1968). Some latent trait models and their use in inferring an examinee’s ability. In Lord F. M., Novick M. R. (Eds.), Statistical theories of mental test scores (pp. 395-479). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Casella G., Berger R. L. (1987). Reconciling Bayesian and frequentist evidence in the one-sided testing problem. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82, 106-111. [Google Scholar]

- Chib S., Greenberg E. (1995), Understanding the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. The American Statistician, 49, 327-335. [Google Scholar]

- *Choo S., Cohen A., Kim S. (2013). Markov chain Monte Carlo estimation of a mixture item response theory model. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, 83, 278-306. [Google Scholar]

- *Curi M., Singer J., Andrade D. (2011). A model for psychiatric questionnaires with embarrassing items. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 20, 451-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis S. M. (2010). BUGS syntax for item response theory. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 1-34. [Google Scholar]

- *De Gooijer J., Yuan A. (2011). Some exact tests for manifest properties of latent trait models. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 55, 34-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *de la Torre J. (2009a). DINA model and parameter estimation: A didactic. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 34, 115-130. [Google Scholar]

- *de la Torre J. (2009b). Improving the quality of ability estimates through multidimensional scoring and interpretation of ancillary variables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 33, 465-485. [Google Scholar]

- *de la Torre J., Hong Y. (2010). Parameter estimation with small sample size: A higher-order IRT model approach. Applied Psychological Measurement, 34, 267-285. [Google Scholar]

- *de la Torre J., Song H. (2009). Simultaneous estimation of overall and domain abilities: A higher-order IRT model approach. Applied Psychological Measurement, 33, 620-639. [Google Scholar]

- *de la Torre J., Song H., Hong Y. (2011). A comparison of four methods of IRT subscoring. Applied Psychological Measurement, 35, 296-316. [Google Scholar]

- *Edwards M. (2010). A Markov chain Monte Carlo approach to confirmatory item factor analysis. Psychometrika, 75, 474-497. [Google Scholar]

- *Etnik R., Fox J.-P., van den Hout A. (2011). A mixture model for the joint analysis of latent development trajectories and survival. Psychometrika, 74, 21-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Etnik R., Fox J.-P., van der Linden W. J. (2011). A multivariate multilevel approach to the modeling of accuracy and speed of test takers. Statistics in Medicine, 30, 2310-2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Finke D. (2009). Estimating the effect of nonseparable preferences in EU treaty negotiations. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 21, 543-569. [Google Scholar]

- Fox J.-P. (2010). Bayesian item response modeling: Theory and applications. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- *Fragoso T., Curi M. (2013). Improving psychometric assessment of the Beck Depression Inventory using multidimensional item response theory. Biometrical Journal, 55, 527-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser C. (1998). NOHARM: A Fortran program for fitting unidimensional and multidimensional normal ogive models in latent trait theory. Armidale, New South Wales, Australia: The University of New England, Center for Behavioral Studies. [Google Scholar]

- *Fu Z.-H., Tao J., Shi N. (2009). Bayesian estimation of the multidimensional three-parameter logistic model. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, 76, 819-835. [Google Scholar]

- *Geerlings H., Glas C., van ser Linden W. (2011). Modeling rule-based item generation. Psychometrika, 76, 337-359. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A. (2013). Running WinBUGS and OpenBUGS from R/S-Plus. Retrieved from http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/R2WinBUGS/R2WinBUGS.pdf

- Hastings W. K. (1970), Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika, 57, 97-109. [Google Scholar]

- *Henson R. A., Templin J., Willse J. (2009). Defining a family of cognitive diagnosis models using log-linear models with latent variables. Psychometrika, 74, 191-210. [Google Scholar]

- *Hsieh C.-A., von Eye A., Maier K. (2010). Using a multivariate multilevel polytomous item response model to study parallel processes of change: The dynamic association between adolescents’ social isolation and engagement with delinquent peers in the National Youth Survey. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45, 508-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Huang H., Wang W., Chen P., Su C. (2013). Higher-order item response models for hierarchical latent traits. Applied Psychological Measurement, 37, 619-637. [Google Scholar]

- *Hung L.-F. (2010). The multigroup multilevel categorical latent growth curve models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45, 359-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hung L.-F. (2011). Formulation and application of the hierarchical generalized random-situation random-weight MIRID. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46, 643-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hung L.-F., Wang W.-C. (2012). The generalized multilevel facets model for longitudinal data. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 37, 231-255. [Google Scholar]

- Jackman S. (2009). Bayesian analysis for the social sciences. Chichester, England: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- *Jang E. (2009). Cognitive diagnostic assessment of L2 reading comprehension ability: Validity arguments for fusion model application to LanguEdge assessment. Language Testing, 26, 31-73. [Google Scholar]

- *Jiao H., Kamata A., Wang S., Jin Y. (2012). A multilevel testlet model for dual local dependence. Journal of Educational Measurement, 49, 82-100. [Google Scholar]

- *Jiao H., Wang S., He W. (2013). Estimation methods for one-parameter testlet models. Journal of Educational Measurement, 50, 186-203. [Google Scholar]

- *Kang T., Cohen A., Sung H.-J. (2009). Model selection indices for polytomous items. Applied Psychological Measurement, 33, 499-518. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-S., Bolt D. M. (2007). Estimating item response theory models using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 26(4), 38-51. [Google Scholar]

- *Kim S., Das S., Chen M.-H., Warren N. (2009). Bayesian structural equation modeling for ordinal response data with missing responses and missing covariates. Communications in Statistics—Theory and Methods, 38, 2748-2768. [Google Scholar]

- *Li F., Cohen A., Kim S.-H., Cho S.-J. (2009). Model selection methods for mixture dichotomous IRT models. Applied Psychological Measurement, 33, 353-373. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Baser R. (2012). Using R and WinBUGS to fit a generalized partial credit model for developing and evaluating patient-reported outcomes assessments. Statistics in Medicine, 31, 2010-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn D. J., Thomas A., Best N., Spiegelhalter D. (2000). Winbugs—A Bayesian modelling framework: Concepts, structure, and extensibility. Statistics and Computing, 10, 325-337. [Google Scholar]

- *Luo S., Ma J., Kieburtz K. (2013). Robust Bayesian inference for multivariate longitudinal data by using normal/independent distributions. Statistics in Medicine, 32, 3812-3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S. M. (2007). Introduction to applied Bayesian statistics and estimation for social scientists. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- MacEachern S. N., Berliner L. M. (1994). Subsampling the Gibbs sampler. The American Statistician, 48, 188-190. [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. D., Quinn K. M., Park J. H. (2011). MCMCpack: Markov chain Monte Carlo in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 42(9), 1-20. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolis N., Rosenbluth A. W., Rosenbluth M. N., Teller A. H., Teller E. (1953), Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. Journal of Chemical Physics, 21, 1087-1092. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolis N., Ulam S. (1949). The Monte Carlo method. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 44, 335-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Meyer J. P. (2010). A mixture Rasch model with item response time components. Applied Psychological Measurement, 34, 521-538. [Google Scholar]

- Muraki E. (1992). A generalized partial credit model: application of an EM algorithm. Applied Psychological Measurement, 16, 159-176. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (1998-2011). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Patz R., Junker B. (1999). A straightforward approach to Markov chain Monte Carlo methods for item response models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 24, 146-178. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2010). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2012). SAS®on demand for academics: Student user’s guide (3rd ed). Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2013). Getting Started with SAS ® Enterprise Miner™ 13.1. Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2014). The MCMC procedure. Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- *Saito M., Iwata N., Kawakame N., Matsuyama Y., & World Mental Health Japan 2002-2003 collaborators. (2010). Evaluation of the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for depressive disorders in a community population in Japan using item response theory. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19, 211-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. (1969). Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. (Psychometrika Monograph No. 17) Richmond, VA: Psychometrics Society. [Google Scholar]

- *Santos J., Azevedo C., Bolfraine H. (2013). A multiple group item response theory model with centered skew-normal latent trait distributions under a Bayesian framework. Journal of Applied Statistics, 40, 2129-2149. [Google Scholar]

- Sinharay S. (2005). Assessing fit of unidimensional item response theory models using a Bayesian approach. Journal of Educational Measurement, 42, 375-394. [Google Scholar]

- *Soares T., Goncalves F., Gamerman D. (2009). An integrated Bayesian model for DIF analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 34, 348-377. [Google Scholar]

- Stan Development Team. 2014. Stan: A C++ library for probability and sampling, Version 2.2. http://mc-stan.org.

- Stone C., Ye F., Zhu X., Lane S. (2009). Providing subscale scores for diagnostic information: A case study when the test is essentially unidimensional. Applied Measurement in Education, 23, 63-86. * [Google Scholar]

- *Tao J., Xu B., Shi N.-Z., Jiao H. (2013). Refining the two-parameter testlet response model by introducing testlet discrimination parameters. Japanese Psychological Research, 55, 284-291. [Google Scholar]

- Tutz G. (1990). Sequential item response models with an ordered response. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 43, 39-55. [Google Scholar]

- *Usami S. (2011). Generalized graded unfolding model with structural equation for subject parameters. Japanese Psychological Research, 53, 221-232. [Google Scholar]

- *van den Hout A., Bockenholt U., ven der Heijden P. (2010). Estimating the prevalence of sensitive behaviour and cheating with a dual design for direct questioning and randomized response. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 59, 723-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wang X., Baldwin S., Wainer H., Bradlow E., Reeve B., Smith A., Bellizzi K., Baumgartner K. (2010). Using testlet response theory to analyze data from a survey of attitude change among breast cancer survivors. Statistics in Medicine, 29, 2018-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L. (2003). BMIRT: Bayesian multivariate item response theory [Computer software]. Monterey, CA: Defense Manpower Data Center. [Google Scholar]

- *Yao L. (2010). Reporting valid and reliable overall scores and domain scores. Journal of Educational Measurement, 47, 339-360. [Google Scholar]