Abstract

We conducted a needs assessment to develop an evidence-based, locally tailored asthma care implementation plan for high risk children with asthma in Chicago. Our team of health policy experts, clinicians, researchers, and designers included extensive stakeholder engagement (N=162) in a mixed-methods community needs assessment. Results showed the lines of communication and collaboration across sectors were weak; caregivers were the only consistent force and could not always manage this burden. A series of recommendations for interventions and how to implement and measure them were generated. Cooperative, multi-disciplinary efforts grounded in the community can target wicked problems such as asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, child, healthcare disparities, research design

Background

Despite many advances in asthma interventions for children, inequities in outcomes persist.1-2 The President’s Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children convened an Asthma Disparities Working Group to align information and federal programs regarding asthma disparities.3 In December of 2014, the National Institutes of Health announced two companion funding opportunities to support implementation research that addressed these disparities. The first was a one-year U34 mechanism to conduct a community needs assessment, design a comprehensive Asthma Care Implementation Program (ACIP), and propose a clinical trial to evaluate the ACIP. The second was a six-year mechanism to implement and evaluate the ACIPs. ACIPs needed to address asthma in four sectors: medical care, family, home, and community.

This national focus on pediatric asthma inequities aligned with local efforts in Chicago, Il, USA.4-8 Strong partnerships existed between asthma advocacy groups, health systems, clinicians, community leaders, schools, local and state public health departments, engineers, and experts in design. Multiple initiatives evolved from these partnerships, including the Coordinated Healthcare Interventions for Childhood Asthma Gaps in Outcomes (CHICAGO) Plan, a multi-center comparative effectiveness trial funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).9 This trial tested an emergency department (ED) discharge tool called the CHICAGO Action Plan after ED discharge (CAPE)10 and community health worker (CHW) home intervention. The PCORI-funded study focused on the ED to home transition but the investigators and partners had a broader vision about opportunities to improve asthma care, which was realized with the receipt of one of the nine U34 awards in September of 2015 (CHICAGO Plan II).

The CHICAGO Plan II was conducted to inform the design of future implementation research for pediatric asthma in Chicago. We sought to actively engage a diverse group of stakeholders who would support a community-based needs assessment (CNA) to determine the essential ACIP components. Stakeholders would review the CNA results and generate a final ACIP as well as determine the design of a research study to evaluate it. In this manuscript, we describe the CHICAGO Plan II process and results, as well as implications that this type of stakeholder engagement and planning can have on implementation research design and program development in areas experiencing health inequities.

Methods

Collaborative Research Team

The CHICAGO Plan II was led by a team of five Principal Investigators (PIs) who represented two community advocacy organizations, a community-based research institute, and a university-based healthcare system. Collaborators included design and qualitative research experts, and experts in asthma technology interventions, implementation science, school asthma interventions, systems engineering, and economic analyses.

The Provisional Asthma Care Implementation Plan (ACIP)

The provisional ACIP was a proposed set of interventions that were supported by a strong evidence base. Our ACIP included a decision support and education tool called the CAPE.10-12 We also incorporated a digital health tool called Propeller Health. Propeller Health is a FDA-cleared, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant digital therapeutic platform that combines inhaler sensors, mobile apps, predictive analytics and personalized feedback to help patients and their physicians better control asthma.13-15 The Propeller sensors passively monitor the use of inhaled medications, capturing the date, time, number of actuations, and geographic location (when paired with a smartphone). These signals provide an objective assessment of adherence to preventive therapy and rescue medication use. Patients and care teams have access to these visualized data through web dashboards and smartphone applications. CHWs (frontline public health workers who are trusted members of the community served)16 were proposed for incorporation into EDs, hospitals, ambulatory clinics, and homes as they have been shown to be associated with a range of improved asthma outcomes.17-19 In schools, the ACIP included education for students with asthma and their adult caregivers, school staff and parents, as well as direct observed therapy of medications in schools, and use of school-based health centers.21-24

Engaging Stakeholders

We used a tiered approach to actively engage diverse stakeholders in the CHICAGO Plan II ACIP. Level 1 stakeholders were organizational leaders who served as advisors to the project with decision-making responsibility. They participated via quarterly phone calls or in-person meetings. Level 2 stakeholders included caregivers of children with asthma and staff/providers in the community who care for these families. They were engaged through the CNA activities and an asthma-specific community advisory board. Level 3 stakeholders included scientific collaborators and consultants who agreed to serve on working groups. Work groups were organized around specific activities. Stakeholders were identified through the wide networks of the PIs and collaborators, via direct outreach, email, web postings, and community meetings.

Community Needs Assessment (CNA)

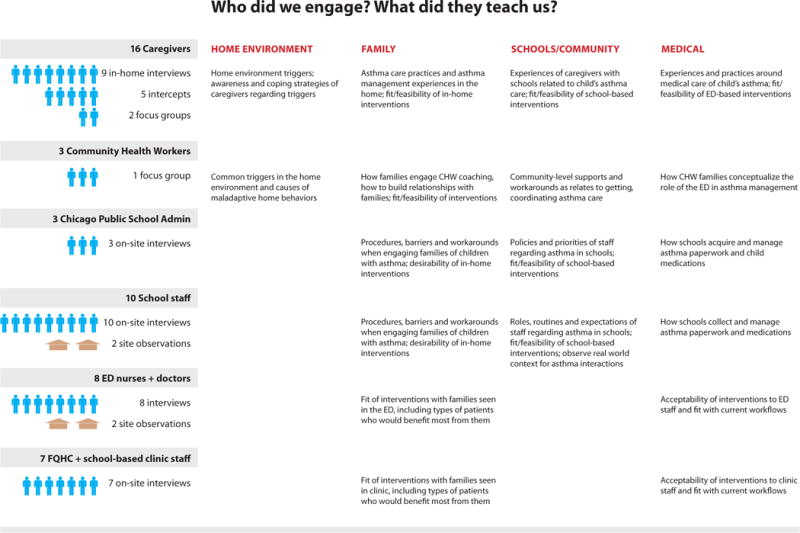

Because of the health disparities focus, we directed our CNA at two regions in Chicago with the highest asthma emergency department (ED) rates for children (247-349 per 10,000 children, the city-wide average is 147 per 10,000) and comparable demographics.8 A range of methods was used (Figure 1).25 To be included, participants either had to work in a healthcare or school setting in one of the two regions, or be a caregiver of a child age 5-14 years old who lived in one of the two regions and had been in the ED for asthma at least once in the past 12 months. Non-English speakers were excluded due to limited resources. Participants were recruited by stakeholder outreach.

Figure 1.

CHICAGO Plan II Community Needs Assessment Participants and Results by Sector

In-person key informant interviews were conducted with organizational leaders in the medical care and schools sectors and clinicians and school staff, to identify resources and barriers to implementing the ACIP. These occurred in the place of employment, lasted about 60 minutes, and informants received a $25 stipend for participation.

Focus groups were conducted with caregivers of children with asthma regarding their experiences with asthma care, as well as the acceptability/feasibility of the ACIP. These lasted about 60 minutes. Caregivers received a $25 stipend for participation.

Individual interviews were conducted with caregivers of children with asthma in their homes in order to explore variances between what participants say they do (in focus groups) versus what they actually do (in the home). These generally last about 120 minutes each. Caregivers received a $50 stipend for participation.

Technology-focused user-centered interviews/observations were conducted using Propeller Health. Providers of pediatric asthma care in both the primary care setting and specialty care setting were recruited from stakeholders. These providers identified children to participate. One family was recruited from other outreach efforts and participated independent of their provider. To be included, children had to have been prescribed an inhaled corticosteroid inhaler and albuterol inhaler (self-report). The Propeller sensors were attached to the participants’ reliever and inhaled corticosteroid medications for one month to monitor the use of inhaled medications. The caregivers and providers were given access to these visualized data through web dashboards and smartphone applications. At the initial visit, caregivers were asked questions about healthcare usage, the home environment, trigger exposure, asthma control, and medication usage. At the end of one month, caregivers and providers were asked again about asthma control and about their experiences with the platform. Caregivers received a $50 stipend at the end of the observation period.

Man-on-the-street intercepts are short interviews conducted with caregivers of children with asthma. These were conducted at community events. Participants had to have a child with asthma to qualify. Caregivers were asked to reflect on ACIP components. Intercepts lasted between 1-20 minutes.

Community user-centered observations were conducted in several clinical and school settings. These are not interviews; they are observations of persons in their natural setting. The investigators observed for 1-2 hours, noting people and processes.

Data from existing sources were compiled and reviewed. This included data from the original CHICAGO Plan I study, City of Chicago data, needs assessments, and other research studies.

Analyses

Verbal interactions were audiotaped and transcribed. Comments and data were categorized into themes, following standard methodology for qualitative research.25 We also employed the POEMS framework 26 (people, objects, environments, messages, and services) to organize observations from schools, EDs, and ambulatory healthcare centers, into the themes. Themes were discussed and modified in multiple research integration sessions that included investigators and community stakeholders. During these sessions, data and themes were visually presented on large storyboards that filled a room; everyone was encouraged to think about the data, ask questions, and make suggestions. These ideas were then incorporated into the data.

Finalize the ACIP using an Implementation Science Framework

A subgroup of investigators and stakeholders reviewed the data themes and integration session feedback, and then finalized and summarized the themes through a process of group discussion. The summarized themes and their implications for the ACIP were presented to the full stakeholder group at an in-person/web streamed meeting and distributed via email for stakeholder input. The results and ACIP were updated to incorporate this feedback.

Design of a clinical implementation trial

Another in-person/web streamed stakeholder meeting was held where the final results and ACIP were presented. Then stakeholders were asked to rank a series of intervention options using the RE-AIM implementation outcomes.27 “Reach” was defined as the amount of eligible children who would receive the intervention and the representativeness of this sample. “Effectiveness” was the potential effect of the intervention on an important outcome. “Adoption” was the percentage of eligible sites that would use the intervention. “Implementation” was the fidelity of the intervention over time and associated costs. “Maintenance” was the ability to sustain the intervention after cessation of grant funding. A score of 5 was the highest or best score that could be given for each proposed option, while 1 was the lowest/worst. Stakeholders were encouraged to think about the practicality of these options if they were implemented in a trial using existing evidence. These scores were used to make decisions on the final trial design, such as which stakeholders should be involved, how to identify and recruit high risk families, and what outcomes to collect.

Ethics, consent, and permissions

This study was approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) at the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board (protocol #2015-0828, covered the Respiratory Health Association, Chicago Asthma Consortium, and Propeller Health), Sinai Health System (MSH#15-44), Illinois Institute of Technology (#2016-004), and the University of Chicago (#16-0510). Participants in the individual interviews, observations, and focus groups provided written informed consent. Participants in the man-on-the-street intercepts provided verbal consent.

Results

In total, 162 stakeholders were engaged representing a wide range of agencies from all four targeted sectors (medical care, family, home, and community) as shown in Figure 2. This was accomplished through nine CHICAGO Plan II project-wide meetings and 31 smaller stakeholder meetings. Stakeholders participated in the CNA design plan, provided input on proposed interventions, facilitated data collection efforts, participated in data analysis, and discussed and ranked study design options.

Figure 2.

CHICAGO Plan II Stakeholder Participants

The CNA results (Table 1) identified two cross-sectional strategies for improving child asthma in Chicago. Because the lines of communication and collaboration across sectors were weak, the results suggested a need for more efficient exchange of information to coordinate care. Second, the CNA identified a need for better, more consistent asthma education and management support from schools, providers, and the community. In the current environment, the job of moving information and coordinating care across sectors fell to caregivers who are often overwhelmed and underprepared to navigate the numerous disconnected systems and requirements of each sector.

Table 1.

CHICAGO Plan 2 Community Needs Assessment Results

Medical Care Sector

|

School/Community Sector

|

Home Environment Sector

|

Family/Child Sector

|

Abbreviations: ED=Emergency Department. EMR=Electronic Medical Record. CAPE=CHICAGO Asthma Plan after ED Discharge. CHW=Community Health Worker.

Three of the explored interventions target these issues directly (Figures 3a and 3b); these interventions became the final ACIP. The first intervention is CHWs that can cross sectors to support caregivers, providers, and schools with information, care coordination, and social support. The second is an electronic version of the CAPE (CHICAGO Asthma Plan for Everyone – CAPE) that supports communication of the asthma management plan among caregivers, providers, and schools. The third is a coordinated approach to asthma education through the schools in order to ensure widespread distribution of information and consistent messaging.

Figure 3. The CHICAGO Plan II Revised Asthma Care Implementation Plan to Address Asthma Inequities in Chicago Children.

a: The Problem

b: The Proposed Solution

- Note that Figure 3a is a modification of the figure published in “Martin MA, Press VG, Nyenhuis SM, Krishnan JA, Erwin K, Mosnaim G, Helen Margellos-Anast H, Paik SM, Ignoffo S, McDermott M, the CHICAGO Plan Consortium. Care transition interventions for children with asthma in the emergency department. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1518-1525.” Permission has been granted.

The last step was to use implementation science methods to apply local experiences and needs to the evidence to determine how to implement and test the final ACIP. A stakeholder meeting was held to discuss and rank RE-AIM implementation outcomes. In total, 23 stakeholders submitted data. Stakeholder rankings were grouped as strongest (4-5), neutral (3), or weak confidence (2-1). Regarding the CHW intervention, 80% or more of stakeholders had strong confidence in the effectiveness and adoption of CHWs in the clinic setting. About half had strong confidence in the implementation and maintenance of CHWs in the clinic setting. Opinions regarding CHWs in the ED and hospital were mixed. Regarding the CAPE intervention, confidence regarding all implementation outcomes for the CAPE was very strong overall but was strongest in the hospital and clinic settings. The strongest role the CAPE could play was felt to be as a communication tool and reminder of the medical plan. Regarding Propeller Health, the effectiveness in the family/child sector and clinic setting was ranked high by most stakeholders. Significant concerns were raised regarding the ability of Propeller Health to have adequate adoption, implementation, and maintenance in the targeted ED and hospital settings due to site-specific issues. Regarding education, about half of stakeholders had high confidence in the parent, child, and school education programs, but confidence in the student-wide asthma education in the schools was low. Regarding reach, payers were ranked as the strongest source for recruitment, followed by clinics and hospitals. Stakeholders were also asked about outcomes that matter to them (Table 2). Asthma control was endorsed as an important outcome by all, with quality of life, costs, and medication usage also almost universally endorsed.

Table 2.

Stakeholder endorsed outcomes of interest for asthma intervention research

| Sector | Family | Home Environment | Schools/ Community | Medical Care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stake-holders | Parent, child, family | Health dept | Housing agencies | Policy and advocacy orgs, EPA | Schools | Policy and advocacy orgs | Tertiary care systems | Ambulatory care systems | Payers |

| Asthma Control | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Quality of life | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Utilization (hospital /ED) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Individual costs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Medication usage | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| School attendance | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| System costs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| HEDIS/ Quality measures | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Asthma rates and plans in schools | X | X | X | X | |||||

An implementation trial design emerged that randomized participants to CHWs alone, CAPE alone, and combined CHW/CAPE. After a delay, the CHWs alone and CAPE alone arms would be offered full intervention. School intervention and CAPE integration into an electronic medical record were added in subgroups after another delay. Interventions were linked to the patients, not the health system, as requested by stakeholders to support sustainability. The investigative team included 15 individuals from clinical care, health services research, City of Chicago, Chicago Public Schools, and service and advocacy agencies. The proposal also engaged 60 advisors representing healthcare systems, government, and social service agencies. Recruitment would occur through Medicaid insurance payers and participating healthcare systems. Multiple outcomes, in the context of the RE-AIM implementation framework, were selected.

Discussion

The CHICAGO Plan II investigators and collaborators conducted a CNA of pediatric asthma in Chicago which resulted in a final ACIP that coordinates CHWs, an electronic communication tool (CAPE), and school-based education. Then stakeholders modified these interventions for fit and feasibility in Chicago. For example, we decided that CHWs needed to be based outside of the healthcare setting in order to: (1) Maintain adequate training, supervision, and support; and (2) Follow patients wherever they go (various EDs, hospitals, and clinics, schools, home). This model would provide well-trained and supervised CHWs that can be contracted by healthcare institutions and payers to provide a wide range of CHW asthma support services to individual patients at high risk. The City of Chicago Department of Public Health played an active role in the entire research process, allowing the final ACIP to align directly with the City’s official health plan.8 The support for the ACIP and process in general was obvious when commitments of support for ACIP implementation were received from Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Department of Public Health, the Chicago Housing Authority, ten healthcare institutions from the Chicago area, five Medicaid managed care organizations, the Illinois Department of Family Services (Medicaid), and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

This research highlights that for many families in Chicago and elsewhere, asthma is just one item on a list of important issues competing for their attention. Caregivers often know what they could do to improve their child’s asthma, but a wide range of barriers prevent this. The healthcare setting tries to support these families but faces its own challenges. Schools, where children spend up to a third of their days, have been making significant strides to service the health needs of their students, but their budgets, staff needs, and other obligations continually challenge their attention and resources.

The issues surrounding pediatric asthma in Chicago are common to other areas where we see health inequities. These health inequities meet criteria to be defined as a wicked problem. A wicked problem involves multiple interacting systems in the social context.29 Often there is no central authority, the persons trying to solve the problem are also causing it, and there are better and worse solutions but no “right” solution.30 Solutions to wicked problems do not have an end and therefore have no clear testable outcome.29 The CHICAGO Plan II serves as a prototype for how cooperative, multi-disciplinary efforts grounded in the community can be used to address wicked problems. Asthma in Chicago affects all sectors of a child’s life and seems to require changes in and between all of these sectors. By engaging stakeholders from all sectors in the process of describing the problems and vetting solution ideas, the CHICAGO Plan II team was able to generate a proposed ACIP that addresses many of the issues surrounding pediatric asthma in Chicago. Some of the methods used in this process are non-traditional. The project was led by community asthma advocacy leaders. Standard qualitative methods were merged with methods from the field of design to inform the fit and feasibility of interventions. Stakeholders used implementation outcomes to determine application of intervention components locally. The results of these efforts was a plan to tackle asthma that was evidence-based and yet tailored to the local community. These efforts also allowed stakeholders to meaningfully invest in the research process and align their programs and policies with research activities. We encourage others to consider similar approaches to wicked problems in healthcare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Joe Gerald, MD, PhD, at the University of Arizona, and Russell Glasgow, MS, PhD, at the University of Colorado. We also would like to thank the staff and students that supported this work: Andrew Bates, Brenna Berlin, Jamie Campbell, Sylvia Cheng, Hongxuan Ge, Janine Grohar, Emily Xiaomeng Jiang, Jennifer Kustwin, Dashana Nair, Jenni Schneiderman, Erica Seltzer Bryan Spence, Sara Tashakorinia, Nicole Twu, and Amanda Weiler.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U34HL130787, Gutierrez, Ignoffo, Krishnan, McMahon, Martin (multi-PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Meredith Barrett works for Propeller Health and receives compensation from Propeller Health. Propeller Health is a for profit company. Stacy Ignoffo worked for Chicago Asthma Consortium (nonprofit, 504c3) and received compensation in that role. Kate McMahon and Amy O'Rourke worked for the Respiratory Health Association (nonprofit, 504c3) and received compensation in that role. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. All of the authors receive funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Martin, Ms. Erwin, Ms. Ignoffo, Ms. McMahon, Dr. Press, and Dr. Krishnan also received funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), award number AS-1307-05420.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/nhis/2014/data.htm. Accessed July 29, 2016.

- 2.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Trends in racial disparities for asthma outcomes among children 0 to 17 years, 2001-2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(3):547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Environmental Protection Agency. President’s task force on environmental health risks and safety risks to children. 2012 May; Available at: https://www.epa.gov/asthma/coordinated-federal-action-plan-reduce-racial-and-ethnic-asthma-disparities. Accessed January 3, 2017.

- 4.Weiss KB, Shannon JJ, Sadowski LS, et al. The burden of asthma in the Chicago community fifteen years after the availability of national asthma guidelines: Results from the CHIRAH study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(3):246–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalowitz MU, Sadowski LM, Kumar R, Weiss KB, Shannon JJ. Asthma burden in a citywide, diverse sample of elementary schoolchildren in Chicago. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(4):271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta RS, Zhang X, Sharp LK, Shannon JJ, Weiss KB. Geographic variability in childhood asthma prevalence in Chicago. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(3):639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margellos-Anast H, Gutierrez M. Pediatric Asthma in Black and Latino Chicago Communities: local level data drives response. In: Whitman S, Shah A, Benjamins M, editors. Urban health: combating disparities with local data. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 247–84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dircksen JC, Prachand NG, et al. Healthy Chicago 2.0: Partnering to Improve Health Equity. City of Chicago: Mar, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan JA, Martin MA, Lohff C, et al. Design of a pragmatic trial in minority children presenting to the emergency department with uncontrolled asthma: The CHICAGO Plan. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017 Mar 30; doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.03.015. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erwin K, Martin MA, Flippin T, et al. Engaging stakeholders to design a comparative effectiveness trial in children with uncontrolled asthma. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5(1):17–30. doi: 10.2217/cer.15.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okelo SO, Butz AM, Sharma R, et al. Interventions to modify health care provider adherence to asthma guidelines: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):517–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ducharme FM, Zemek RL, Chalut D, et al. Written action plan in pediatric emergency room improves asthma prescribing, adherence and control. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:195–203. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0115OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merchant RK, Inamdar R, Quade RC. Effectiveness of population health management using the propeller health asthma platform: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Prac. 2016;4(3):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su JG, Barrett MA, Henderson K, et al. Feasibility of Deploying Inhaler Sensors to Identify the Impacts of Environmental Triggers and Built Environment Factors on Asthma Short-Acting Bronchodilator Use. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(2):254–261. doi: 10.1289/EHP266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Sickle D, Maenner M, Barrett M, Marcus J. Monitoring and improving compliance and asthma control: mapping inhaler use for feedback to patients, physicians and payers. Resp Drug Delivery Europe. 2013:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Public Health Association. Community Health Workers. doi: 10.2190/NS.20.3.l. Available at https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers Accessed February 9, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Campbell JD, Brooks M, Hosokawa P, Robinson J, Song L, Krieger J. Community Health Worker Home Visits for Medicaid-Enrolled Children With Asthma: Effects on Asthma Outcomes and Costs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2366–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crocker DD, Kinyota S, Dumitru GG, et al. Effectiveness of home-based, multi-trigger, multicomponent interventions with an environmental focus for reducing asthma morbidity: a community guide systematic review. Task force on community preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2S1):S5–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postma J, Karr C, Kieckhefer G. Community health workers and environmental interventions for children with asthma: a systematic review. J Asthma. 2009;46(6):564–76. doi: 10.1080/02770900902912638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merchant RK, Inamdar R, Henderson K, Barrett M, Van Sickle D. Patient reported value and usability of a digital health intervention for asthma. J Med Internet Res. 2016;2(1):e36. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.7362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerald L, McClure L, Mangan J, et al. Increasing Adherence to Inhaled Steroid Therapy Among Schoolchildren: Randomized, Controlled Trial of School-Based Supervised Asthma Therapy. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):466–474. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler L, Merkle S, Gerald L, Taggart V. Managing Asthma in Schools: Lessons Learned and Recommendations. J Sch Health. 2006;76(6):340–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosnaim GS, Li H, Damitz M, et al. Evaluation of the Fight Asthma Now (FAN) program to improve asthma knowledge in urban youth and teenagers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;107(4):310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo JJ, Jang R, Keller KN, McCracken AL, Pan W, Cluxton RJ. Impact of school-based health centers on children with asthma. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontana AFJ. Chapter 24: The interview from structured questions to negotiated text. In: Denzin Norman K, Lincoln Yvonne S., editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Second. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar V. POEMS 101 Design Methods: A structural approach for driving innovation in your organization. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin MA, Press VG, Nyenhuis SM, et al. Care transition interventions for children with asthma in the emergency department. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1518–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences. 1973;4:155–169. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levin K, Cashore B, Bernstein S, Auld G. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences. 2012;45:123–152. [Google Scholar]