Abstract

A 48-year-old man, former alcohol abuser and drug addicted, was referred to our tertiary referral centre for iron disorders because of marked hyperferritinaemia. His clinical history revealed chronic hepatitis C, ß-thalassaemia trait and post-traumatic splenectomy at age of 22. MRI-estimated liver iron content was markedly elevated, while first-line genetic test for haemochromatosis was negative. Alpha-fetoprotein was increased but liver ultrasonography did not reveal focal liver lesions. Multiphasic contrast-enhanced CT confirmed this result but showed two abdominal masses (diameter of 9 cm and 7 cm, respectively) among bowel loops, strongly suspicious for cancer. However, biopsy of one of the masses led to the final diagnosis of abdominal splenosis.

Keywords: liver disease, haematology (incl blood transfusion), radiology

Background

The term splenosis was coined in 1939 by Buckbinder and Lipkoff, describing a woman with multiple peritoneal nodules found at laparotomy, initially attributed to endometriosis, but later proven to be splenic tissue by histopathology.1 Splenosis is related to ectopic implants of splenic tissue from spillage of cells from the splenic pulp after abdominal trauma, unwanted splenic damage during abdominal surgery for other reasons or splenectomy.2 Implants are often multiple and can occur anywhere in the peritoneal cavity, but also in the thorax, retroperitoneum or pelvis. In some cases, cells from the splenic pulp can implant into the liver mimicking a hepatic tumour.3 The incidence of splenosis is widely variable, being reported in 25%–65% of patients splenectomised after trauma and in 16%–20% of those undergoing elective splenectomy for haematological disorders.4–6 Diagnosis is often challenging and should be considered whenever intraperitoneal nodules of uncertain significance are incidentally found decades after splenectomy, possibly raising a misleading suspicion of malignancy.7 Most patients are asymptomatic, but complications including haemorrhage, pain or bowel obstruction can rarely occur.8 Of note, splenosis can sometimes functionally revert asplenia when the ectopic splenic mass is higher than 20–30 cm3, resulting in the disappearence of erythrocytes Howell-Jolly bodies on peripheral blood smear.4 Definitive diagnosis of splenosis often requires scintigraphy using either 99technetium-labelled erythrocytes or 111indium-labelled platelets.9

Although splenosis could be a possibility in our patient, unusual and misleading CT features were apparently consistent with malignancy, particularly because of contrast enhancement. A posteriori, this was interpreted as due to iron overload in the ectopic splenic tissue after Pearl’s staining of histological specimens. We believe that this unique and puzzling case represents an instructive example of the need of never taking anything for granted in the clinic.

Case presentation

A 48-year-old unemployed man was referred to our tertiary referral centre for iron disorders because of marked hyperferritinaemia. He declared previous heavy alcohol consumption, drug addiction and risky sexual behaviour (male heterosexual sex worker). His clinical history revealed chronic hepatitis C, ß-thalassaemia trait and post-traumatic splenectomy at age of 22. The physical examination was consistent with presence of chronic liver disease, showing mild jaundice and spider naevi.

Investigations

Blood tests confirmed a marked increase of serum ferritin (about 4000 µg/L) and transferrin saturation (88%), as well as mild hypertransaminasaemia (aspartate aminotransferase 78 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 89 U/L), increased bilirubin (4 mg/dL), prolonged prothrombin time international normalised ratio (1.5) and mild decrease of albumin (33 g/L). A clinical diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was made, with Child-Pugh score being B8. Genetic testing for haemochromatosis did not reveal classical HFE mutations, that is, C282Y and H63D. Liver iron content estimation by MRI-based Gandon’s protocol yielded 290±30 µM/g (normal value <36 µM/g), suggesting severe iron overload. Liver biopsy was proposed, but the patient refused the procedure. We hypothesised a multifactorial iron overload based on the history of alcohol abuse, chronic hepatitis C and ß-thalassaemia trait. Further staging of chronic liver disease through liver ultrasonography and α-FP showed a sustained increase of the latter biomarker (28.8 µg/L) without liver focal lesions.

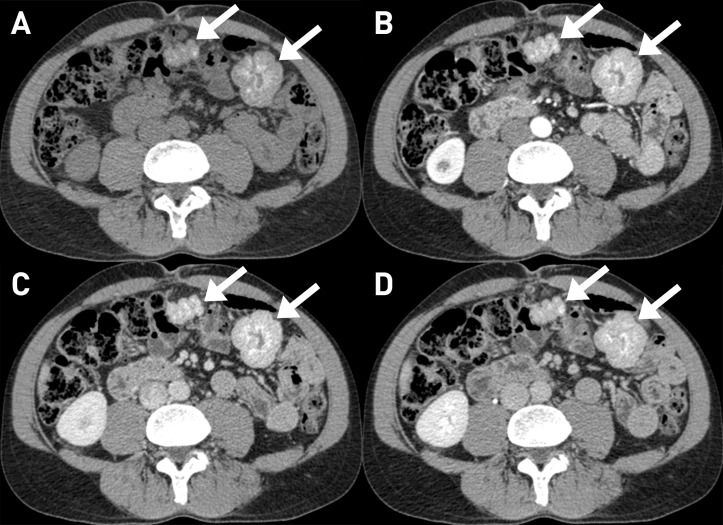

An abdominal multiphasic contrast-enhanced CT was then performed, confirming the absence of suspected liver nodules. However, two well-defined exophytic solid masses, with diameter of 9 cm and 7 cm, respectively, were seen among the bowel loops. They appeared lobulated with smooth margins and many tiny hyperdense foci. The contrast enhancement was progressive and heterogeneous (figure 1).

Figure 1.

CT appearance of the two solid masses (arrows) among bowel loops; they were exophytic, well-defined, lobulated masses, with smooth margin and heterogeneous appearance with the presence of many tiny hyperdense foci (A: without contrast). The contrast enhancement was progressive and heterogeneous in the three phases (B: arterial; C: venous; D: late).

Differential diagnosis

Based on the imaging features, the radiologist proposed a differential diagnosis including:

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour, as the masses were intimately connected with the small bowel with exophytic, well-defined appearance and, possibly, small calcifications.

Lymphoma, which can unusually presents like small bowel masses, although the absence of lymphadenopathy elsewhere made this diagnosis less probable.

Desmoid tumour, which can appear as a well-defined mass, while usually lacking calcifications.

Leiomyoma, although calcifications and multiple localisations tended to rule out this condition.

Metastatic masses could not completely ruled out, notwithstanding the absence of a visible primary tumour.

An ultrasound-guided tru-cut biopsy was then eventually performed without complications.

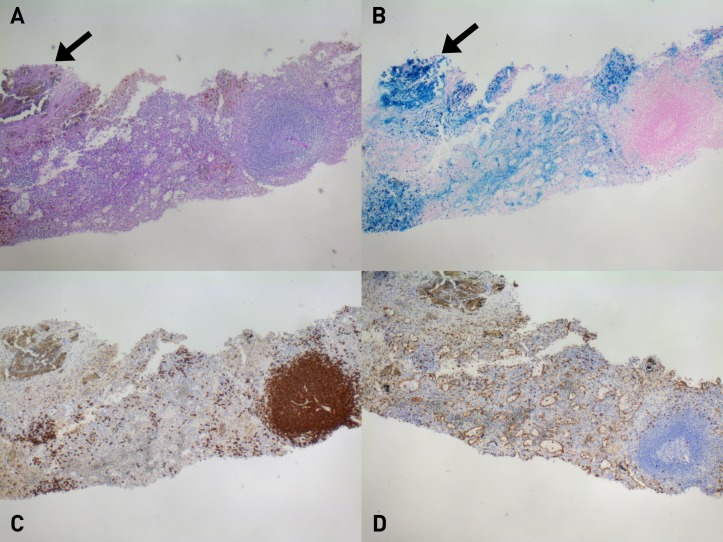

Histopathological examination provided a diagnosis of abdominal splenosis, showing the presence of spleen tissue with Gandy–Gamna bodies (haemosiderin accumulation due to scarring of the splenic tissue subsequent to perivascular haemorrhages) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histological exam of the abdominal mass that underwent tru-cut biopsy shows splenic tissue with iron overload. Haemosiderin granules are visible in A (Periodic acid–Schiff stain) and even clearly in B (Pearls stain); also a Gandy–Gamna body is included (arrow). In C (CD20 immunohistochemical stain) and D (CD8 immunohistochemical stain), respectively, visible are a germinal centre and splenic sinusoids.

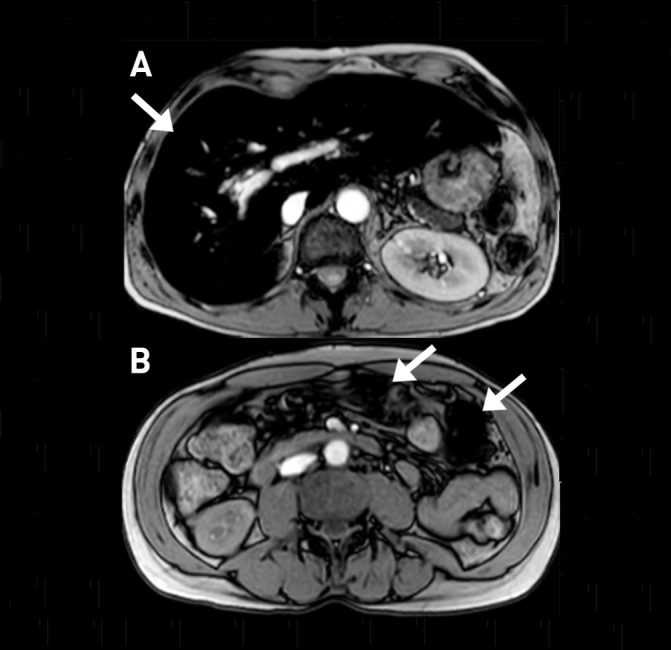

A posteriori, the small hyperdensities noted within the masses were deemed to reflect haemosiderin accumulations in this iron-overloaded patient, rather than calcifications. This was confirmed by performing MRI with multiple gradient echo sequences, showing a marked paramagnetic effect of the heterotopic splenunculi, reflecting their high iron content (figure 3).

Figure 3.

In this two gradient echo T2-weighted images, the liver (A: arrow) is markedly hypointense due to its high iron content (superparamagnetic effect); the iron accumulation is so high in the two splenunculi (B: arrows) to determine a ferromagnetic artefact.

Treatment

At the time of the visit, the patient had already regularised his lifestyle, which was essential cornerstone for prognosis. Removal of iron overload is challenging in patients with ß-thalassaemia trait, since the mild anaemia precludes classical intensive phlebotomy regimens (removal of 450–500 mL every 7–10 days) commonly used in hereditary haemochromatosis. Oral iron chelators (deferasirox and deferiprone) are approved only in ß-thalassaemia major and intermedia, while deferoxamine requires cumbersome nightly subcutaneous infusions through a micropump. Since the patient initially denied such approach, we pragmatically prescribed a ‘mini-phlebothomy’ programme, consisting in removal of 150–200 mL of blood every 10–14 days. Finally, a therapy for genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, including sofosbuvir, simeprevir and ribavirin, was prescribed.

Outcome and follow-up

Abdominal splenosis does not need any specific treatment in absence of complications. We only performed a radiological follow-up, showing no significant changes over time. The first-line antiviral protocol failed to eradicate the infection; however, a second-line therapy with sofosbuvir, ledipasvir and ribavirin successfully eradicated the virus. Serum ferritin decreased from 4000 to 1500 and Child-Pugh score decreased from B8 to A6. The patient is currently followed at our centre for chronic liver disease and iron overload, with the aim to reach iron depletion.

Discussion

This case was challenging for both clinicians and radiologists. From a clinical perspective, the multifactorial nature of iron overload is remarkable. Both HCV10 and alcohol11 are well-established downregulators of hepcidin, the key hormone that normally inhibits intestinal iron absorption. Moreover, this patient was also a carrier of the ß-thalassaemia trait, in which a further downregulation of hepcidin by erythroferrone12 has been recently proposed.13 The combination of such multiple factors was likely the cause of the severe iron overload in this patient. For the same reasons, this cirrhotic patient could be considered at high risk of cancer, particularly of hepatocellular carcinoma.

In this case, the strong suspicion of cancer and the imaging features of the abdominal masses represented diagnostic pitfalls. Even knowing that the patient had a previous splenectomy, in this particular case the presence of multiple hyperdensities and the unusual enhancement due to iron deposition initially brought to misdiagnosis. Tru-cut biopsy eventually led to the right diagnosis and correct interpretation of imaging findings.

Learning points.

Splenosis has to be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal masses, and it is often mistaken for cancer.

Iron overload is often multifactorial, particularly when severe.

A strong partnership between clinicians and radiologists is essential to avoid misinterpretations.

Footnotes

Contributors: GM collected the clinical data and wrote the manuscript. GA collected the radiological data and cowrote the manuscript. AZ provided histological images and cowrote the manuscript. DG supervised the clinical management of the patient and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Buckbinder JH, Lipkoff CJ. Splenosis: multiple peritoneal splenic implants following abdominal injury. Surgery 1939;6:927–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrier SL. Approach to the adult with splenomegaly and other splenic disorders. Massachusetts, USA: UpToDate, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson LA, Reid IN. Intrahepatic splenic tissue. J Clin Pathol 1997;50:532–3. 10.1136/jcp.50.6.532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corazza GR, Tarozzi C, Vaira D, et al. Return of splenic function after splenectomy: how much tissue is needed? Br Med J 1984;289:861–4. 10.1136/bmj.289.6449.861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derin H, Yetkin E, Ozkilic H, et al. Detection of splenosis by radionuclide scanning. Br J Radiol 1987;60:873–5. 10.1259/0007-1285-60-717-873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livingston CD, Levine BA, Lecklitner ML, et al. Incidence and function of residual splenic tissue following splenectomy for trauma in adults. Arch Surg 1983;118:617–20. 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390050083016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mpe M, Schauer C. Splenosis mimicking cancer. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2016;374:1965 10.1056/NEJMicm1512086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varughese N, Duong A, Emre S, et al. Venting the spleen. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2013;369:1357–63. 10.1056/NEJMcps1210943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lake ST, Johnson PT, Kawamoto S, et al. CT of splenosis: patterns and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199:W686–W693. 10.2214/AJR.11.7896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girelli D, Pasino M, Goodnough JB, et al. Reduced serum hepcidin levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2009;51:845–52. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison-Findik DD, Schafer D, Klein E, et al. Alcohol metabolism-mediated oxidative stress down-regulates hepcidin transcription and leads to increased duodenal iron transporter expression. J Biol Chem 2006;281:22974–82. 10.1074/jbc.M602098200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kautz L, Jung G, Valore EV, et al. Identification of erythroferrone as an erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. Nat Genet 2014;46:678–84. 10.1038/ng.2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones E, Pasricha SR, Allen A, et al. Hepcidin is suppressed by erythropoiesis in hemoglobin E β-thalassemia and β-thalassemia trait. Blood 2015;125:873–80. 10.1182/blood-2014-10-606491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]