Abstract

Objective:

To use the patient outcome endpoints overall survival and progression-free survival to evaluate functional parameters derived from dynamic contrast-enhanced CT.

Methods:

69 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma had dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scans at baseline and after 5 and 10 weeks of treatment. Blood volume, blood flow and standardized perfusion values were calculated using deconvolution (BVdeconv, BFdeconv and SPVdeconv), blood flow and standardized perfusion values using maximum slope (BFmax and SPVmax) and blood volume and permeability surface area product using the Patlak model (BVpatlak and PS). Histogram data for each were extracted and associated to patient outcomes. Correlations and agreements were also assessed.

Results:

The strongest associations were observed between patient outcome and medians and modes for BVdeconv, BVpatlak and BFdeconv at baseline and during the early ontreatment period (p < 0.05 for all). For the relative changes in median and mode between baseline and weeks 5 and 10, PS seemed to have opposite associations dependent on treatment.

Interobserver correlations were excellent (r ≥ 0.9, p < 0.001) with good agreement for BFdeconv, BFmax, SPVdeconv and SPVmax and moderate to good (0.5 < r < 0.7, p < 0.001) for BVdeconv and BVpatlak. Medians had a better reproducibility than modes.

Conclusion:

Patient outcome was used to identify the best functional imaging parameters in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Taking patient outcome and reproducibility into account, BVdeconv, BVpatlak and BFdeconv provide the most clinically meaningful information, whereas PS seems to be treatment dependent. Standardization of acquisition protocols and post-processing software is necessary for future clinical utilization.

Advances in knowledge:

Taking patient outcome and reproducibility into account, BVdeconv, BVpatlak and BFdeconv provide the most clinically meaningful information. PS seems to be treatment dependent.

Introduction

Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT (DCE-CT) enables the quantification of absolute physiological parameters such as blood volume (BV), blood flow (BF), permeability surface area (PS) and mean transit time as well as semi-quantitative parameters such as time to peak enhancement.1, 2 Quantification of the absolute physiological parameters can be done using a number of different mathematical models, most of which have specific assumptions built into the model. For general body DCE-CT, the most commonly used models are based on Fick’s principle (maximum slope3 and conventional compartment models, CC), Patlak analysis4, 5 and deconvolution using the adiabatic approximation of tissue homogeneity (AATH)6—all of which are integrated into commercial products.1

Quantification of the DCE-CT parameters in tissue with a single blood supply is primarily done using the first pass of the contrast media. The models built on Fick’s principle assume that the different compartments (primarily intravascular extracellular and extravascular extracellular) are well mixed. More specifically, the maximum slope model assumes no venous outflow, making it only applicable during first pass.3 Patlak is a two-compartment model in which one-way flow is assumed. The Patlak plot is linear allowing for linear regression when flow from the intravascular to the extracellular space is dominant.4 AATH deconvolution assumes a concentration gradient in the capillary, but a well-mixed interstitium.6

Only few clinical studies of solid tumours have compared DCE-CT parameters using two or more mathematical models to analyse the same patient scans.7–15 Of these, two have attempted to correlate differently derived DCE-CT parameters to patient survival.11, 13

The aim of this explorative study was to identify which DCE-CT functional parameters, including time point(s), statistical parameter(s) and mathematical model(s) used in the calculation of the DCE-CT parameters, had the best correlations to patient outcome endpoints in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. As an integral part of the exploration of possible imaging biomarkers, interobserver correlations and agreement were also tested.

Methods and materials

Patients and scan parameters

92 patients from 2 studies, the Danish Renal Cancer Group Study-1 (DARENCA-1) and the Angiogenesis Inhibitor Study (AIS), receiving systemic treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma were included in this analysis. DARENCA-1 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01274273)16 was a randomized Phase II clinical trial comparing subcutaneously administered interleukin-2-based immunotherapy with and without the intravenous angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab (Avastin; Roche, Basel, Switzerland). AIS is an ongoing cohort study of patients receiving routine first-line angiogenesis inhibitors. The regional ethics committee approved both studies and all patients gave written informed consent prior to inclusion.

In both studies, patients were scanned with DCE-CT before treatment start and after 5 and 10 weeks of treatment. DCE-CT scans were performed using a Philips Brilliance 64 or iCT Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) with a scan cycle every 2 s during a period of 70 s. Patients received intravenous administration of 60 ml iodixanol (Visipaque; GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ) 270 mg iodine ml−1 or 60 ml iohexol (Omnipaque; GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ) 300 mg iodine ml−1 at 6 ml s−1 in connection with the DCE-CT scans. Median acquisition parameters were 8 cm z-axis length (4–16 cm), 80 kVp (80–120 kVp) and 100 mAs (80–210 mAs). For DCE-CT analysis, 5 mm axial image reconstructions were used.

At baseline, week 10 and every 12 weeks thereafter, all patients also received routine contrast-enhanced CT scans of the thorax, abdomen and pelvic regions (120 kVp, attenuation-based current-modulation, 64 or 128 × 0.625 mm collimation, pitch 0.925, tube rotation time 0.75 s) using bolus-tracking technique with iodixanol 270 mg iodine ml−1 or iohexol 300 mg iodine ml–1 at 2 ml kg–1 body weight (max. 180 ml) and injection velocities of 4 ml s−1. These routine scans were assessed using response criteria in solid tumours (RECIST) 1.1, and the clinical decision-making was based on these results.

Imaging analysis

Of the 92 patients included, baseline scans for 23 patients were unable to be analysed owing to movement artefacts (n = 18) and other technical issues (n = 5). Thus, 69 patients were included in the analyses in the present manuscript. Follow-up time ranged from 13.8 to 60.7 months with a median of 33.6 months. It should be noted that a recently published article, which examines the clinical implications of DCE-CT in further detail while building upon the conclusions drawn in the present manuscript, was based on the same patients.17 A small number of these patients (n = 12) were also used in an earlier preliminary study using less advanced software.18

The four-dimensional DCE-CT scan series were loaded into the Advanced Perfusion and Permeability Application software (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands), and after non-rigid registration and spatial filtration, a region of interest was drawn in a large artery (usually aorta) while carefully avoiding partial volume effects. Nine different quantitative and semi-quantitative parameters were calculated (Figure 1a): blood volume using deconvolution (BVdeconv, ml × 100 g−1) and using the Patlak model (BVpatlak, ml × 100 g−1); blood flow using deconvolution (BFdeconv, ml × min−1 × 100 g−1) and using the maximum slope model (BFmax, ml × min−1 × 100 g−1); standardized perfusion values using deconvolution (SPVdeconv, no units) and using the maximum slope model (SPVmax, no units); permeability surface area product using the Patlak model (PS, ml × min−1 × 100 g−1); mean transit time (s); and time to peak (s).

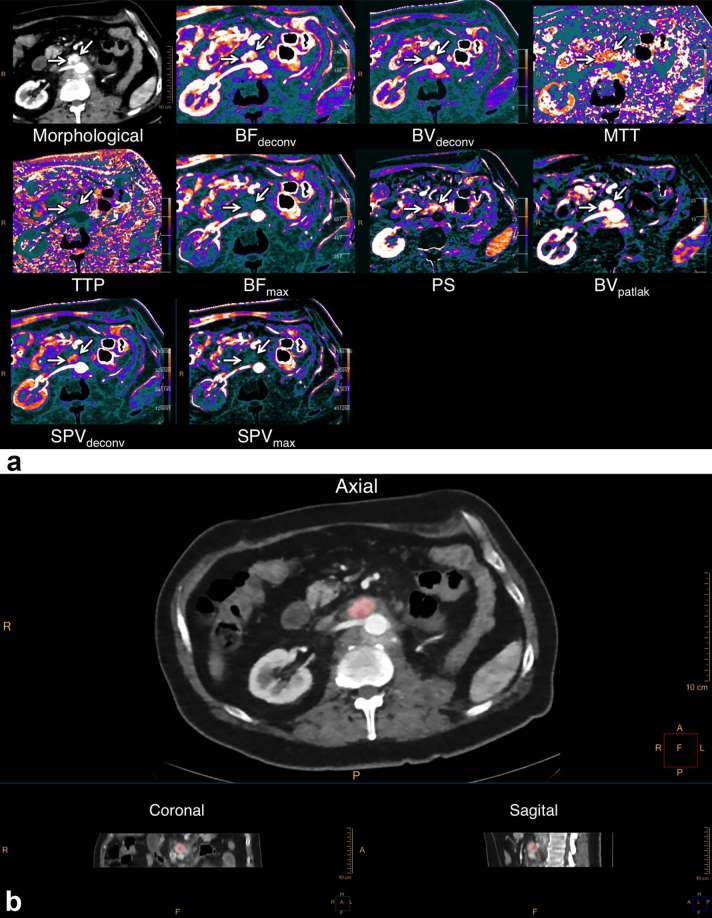

Figure 1.

Imaging analysis using the prototype APPA program. (a) Using a manually designated arterial input function, APPA calculates a number of different functional imaging parameters, here displayed as colour maps. (b) Three-dimensional delineation of the lymph node metastasis is done in Tumor Tracking and the resulting pixel-by-pixel data for each parameter are extracted as histograms such as those depicted in Figure 2. APPA, advanced perfusion and permeability application; BF, blood flow; BV, blood volume; MTT, mean transit time; PS, permeability surface area product; SPV, standardized perfusion value; TTP, time to peak.

Advanced Perfusion and Permeability Application uses an exact maximum likelihood expectation maximization deconvolution technique. The standardized parameters SPVdeconv and SPVmax are modelled after Miles et al19.

A data set for each of the DCE-CT parameters was calculated and was then saved as a series for each parameter and loaded into Intellispace v. 6.0 Multimodality Tumor Tracking (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) together with a series created from the time of peak tumour enhancement. Using the peak tumour enhancement series, the tumour was delineated using a three-dimensional semi-automatic sculpt tool (Figure 1b). When the tumour was sufficiently delineated, each of the DCE-CT parameter series were chosen individually and histograms were displayed showing the distribution of values on the x-axis and number of pixels on the y-axis. The histograms were then extracted for each DCE-CT parameter as a comma-separated file (.csv) for each patient at each available time point. Examples of extracted histograms are shown in Figure 2. Because of technical limitations, mean transit time and time to peak could not be extracted for analysis.

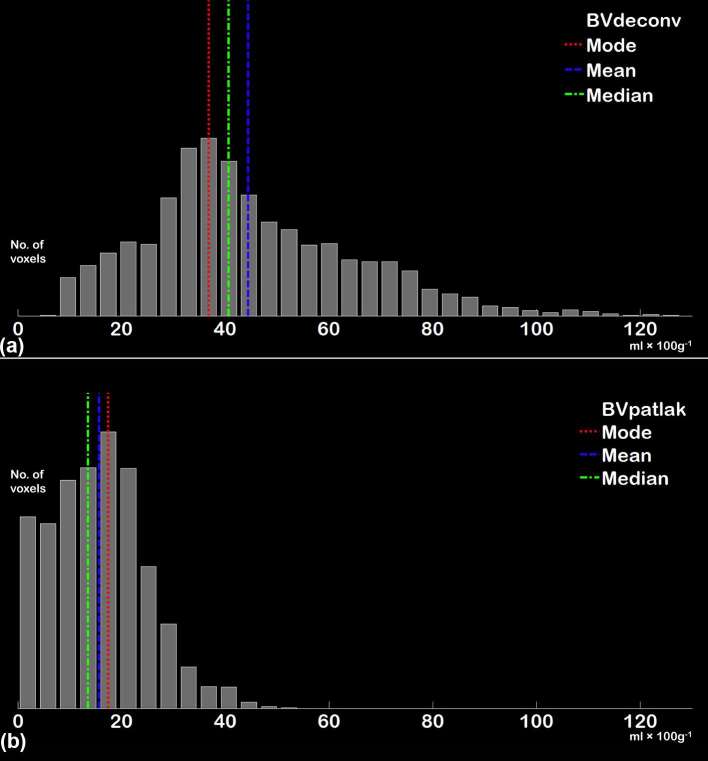

Figure 2.

Histograms from BVdeconv (a) and BVpatlak (b) in a single patient based on data extracted from APPA using the same tumour delineation for both parameters. Histograms with a configuration similar to (a) were most commonly seen using the deconvolution and max slope methods of calculation (BVdeconv, BFdeconv, BFmax, SPVdeconv and SPVmax) while histograms similar to (b) were more commonly seen when using the Patlak method of calculation (BVpatlak and PS). APPA, advanced perfusion and permeability application; BF, blood flow; BV, blood volume; PS, permeability surface; SPV, standardized perfusion value.

Statistical analysis

Using an in-house script developed in Matlab (v. R2011b, MathWorks, Natick, MA), the upper and lower 1/1000 numerical values were removed from all histograms, and the following parameters were calculated for each histogram: median, mean, mode, standard deviation, interquartile range, skewness and kurtosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Median and range (in parentheses) for all parameters found using histogram analysis on each lesion

| BVdeconv ml × 100 g−1 | BVpatlak ml × 100 g−1 | BFdeconv ml × min–1 × 100 g−1 | BFmax ml × min–1 × 100 g−1 | SPVdeconv | SPVmax | PS ml ×min–1 × 100 g−1 | ||

| Median (range) N = no. of scans | Baseline | 34.9 (13.1–102.9) N = 69 | 22.4 (4.8–63.9) N = 68 | 200.2 (71.6–434.6) N = 69 | 387.4 (91.0–1240.0) N = 69 | 17.9 (3.6–44.9) N = 69 | 40.5 (5.3–120.3) N = 69 | 22.1 (9.7–61.7) N = 69 |

| All | 30.3 (9.4–117.5) N = 184 | 20.3 (4.8–101.5) N = 183 | 172.7 (9.5–656.9) N = 185 | 367.3 (84.7–1753.1) N = 185 | 17.0 (3.1–56.6) N = 184 | 35.8 (4.6–150.5) N = 184 | 21.9 (5.8–75.1) N = 183 | |

| Mean (range) N = no. of scans | Baseline | 40.0 (13.7–109.0) N = 69 | 23.7 (5.6–84.0) N = 68 | 211.9 (75.4–519.4) N = 69 | 466.3 (100.0–1675.7) N = 69 | 20.8 (6.0–52.0) N = 69 | 45.8 (8.9–162.9) N = 69 | 23.7 (11.3–69.1) N = 69 |

| All | 34.0 (11.0–113.6) N = 184 | 22.0 (5.6–140.3) N = 183 | 191.8 (10.8–679.4) N = 185 | 421.8 (100.0–2077.4) N = 185 | 18.4 (3.12–58.3) N = 184 | 40.6 (8.2–162.9) N = 184 | 24.0 (8.8–72.6) N = 183 | |

| Mode (range) N = no. of scans | Baseline | 29.8 (4.9–76.3) N = 69 | 17.0 (0.7–72.2) N = 68 | 161.0 (0.9–416.3) N = 69 | 313.3 (0.9–800.0) N = 69 | 11.9 (0–46.7) N = 69 | 28.5 (0–83.9) N = 69 | 13.1 (0.7–47.2) N = 69 |

| All | 25.0 (0.9–76.3) N = 184 | 9.9 (0.7–72.2) N = 183 | 126.1 (0.8–549.1) N = 185 | 274.5 (0.8–922.7) N = 185 | 12.0 (0–49.4) N = 184 | 24.3 (0–118.1) N = 184 | 10.4 (0.7–102.4) N = 184 | |

| Standard deviation (range) N = no. of scans | Baseline | 15.3 (0–95.1) N = 69 | 9.3 (0–95.4) N = 68 | 80.6 (18.5–443.3) N = 69 | 213.4 (51.5–1381.9) N = 69 | 8.1 (1.5–27.8) N = 69 | 19.6 (4.6–113.9) N = 69 | 11.6 (4.7–63.7) N = 69 |

| All | 13.6 (0–95.6) N = 184 | 9.1 (0–134.6) N = 183 | 73.6 (1.8–452.4) N = 185 | 184.1 (28.9–1895.0) N = 185 | 7.3 (0.6–42.0) N = 184 | 16.9 (3.8–151.8) N = 184 | 11.6 (0–87.2) N = 183 | |

| Interquartile range (range) N = no. of scans | Baseline | 18.8 (0–88.0) N = 69 | 12.3 (0–100.8) N = 68 | 87.2 (21.2–487.2) N = 69 | 194.0 (50.2–1722.6) N = 69 | 8.1 (1.75–37.9) N = 69 | 19.8 (3.6–150.9) N = 69 | 14.9 (0–44.0) N = 69 |

| All | 15.5 (0–156.6) N = 184 | 11.6 (0–164.0) N = 183 | 81.7 (3.8–809.1) N = 185 | 181.0 (35.2–3488.7) N = 185 | 7.9 (0.8–69.5) N = 184 | 18.3 (3.55–265.2) N = 184 | 15.0 (0–66.9) N = 183 | |

| Skewness (range) N = no. of scans | Baseline | 1.1 (−0.7 to + 9.1) N = 68 | 0.67 (−1.1 to + 4.5) N = 68 | 1.1 (− 1.0 to + 6.9) N = 69 | 1.4 (−0.3 to + 7.1) N = 69 | 1.1 (−1.0 to + 7.0) N = 69 | 1.4 (−0.3 to + 7.0) N = 69 | 0.9 (−0.5 to + 5.6) N = 69 |

| All | 1.1 (−0.7 to + 9.1) N = 183 | 1.0 (−1.1 to + 6.9) N = 183 | 1.1 (−1.0 to + 6.9) N = 185 | 1.4 (−0.3 to 7.2) N = 185 | 1.1 (−1.0 to + 7.0) N = 184 | 1.4 (−0.3 to + 7.2) N = 184 | 0.9 (−0.5 to 5.6) N = 183 | |

| Kurtosis (range) N = no. of scans | Baseline | 4.1 (2.1–110.6) N = 68 | 3.4 (1.0–25.1) N = 68 | 5.8 (2.3–76.8) N = 69 | 6.4 (2.5–99.3) N = 69 | 5.8 (2.3–76.8) N = 69 | 6.4 (2.5–96.8) N = 69 | 3.9 (1.9–37.8) N = 69 |

| All | 4.3 (1.8–110.6) N = 183 | 3.8 (1.0–58.2) N = 183 | 4.8 (1.4–78.5) N = 185 | 5.2 (1.6–99.4) N = 185 | 4.9 (2.0–83.9) N = 184 | 5.2 (1.6–96.8) N = 184 | 3.5 (1.0–37.8) N = 183 | |

BF, blood flow; BV, blood volume; SPV, standardized perfusion value.

“Baseline” (n = 69) includes only baseline dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scans to remove any bias caused by treatment or by different numbers of scans per patient. “All” (n = 185) is based on all available dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scans from baseline, weeks 5 and 10 for the 69 patients included in the analysis.

For median, mode, interquartile range, skewness and kurtosis, the relative change between baseline and ontreatment weeks 5 and 10 was calculated using the following equation:

The absolute values as well as the values for relative change were then examined for associations with progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) using Kaplan–Meier curves and log rank tests (SPSS Statistics software v. 20.0.0.1, IBM Corporation, Armunk, NY). PFS was defined as the time from study inclusion to progression as per RECIST or cancer-related death (whichever came first). OS was defined as the time from study inclusion to cancer-related death. If the endpoint was not reached, data were censored at the last date of follow up.

To explore the correlations between different mathematical models, the different blood volume parameters (BVdeconv and BVpatlak) and perfusion parameters (BFdeconv, BFmax, SPVdeconv and SPVmax) were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation (SPSS), linear regression and Bland-Altman plots (Excel for Mac 2011 v. 14.6.1; Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

To assess interobserver correlations, a second radiologist with experience in DCE-CT independently analysed the tumours from a subgroup of the patients (n = 49) using the same procedure as previously described. Interobserver correlation and agreement for median and mode of each DCE-CT parameter was then examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (SPSS), linear regression and Bland-Altman plots (Excel).

Results

Imaging parameters and patient outcome endpoints

From the histogram analysis using median, mode, interquartile interval, kurtosis and skewness, statistically significant associations to patient outcome were observed for median at baseline (OS: p < 0.05 for BVdeconv, BFdeconv and SPVdeconv), week 5 (OS: p < 0.05 for BFdeconv, BFmax, SPVdeconv and SPVmax) and for the relative changes from baseline to week 5 (PFS: p < 0.05 for BVdecon, BVpatlak and BFdeconv) and to week 10 (PFS: p < 0.05 for BVdeconv) (Table 2). Significant associations to patient outcome were also observed for mode at baseline (OS: p < 0.05 for BVpatlak, BFdeconv and SPVdeconv) and for the relative changes from baseline to week 5 (PFS: p < 0.05 for BVdeconv, BVpatlak, BFdeconv, BFmax and SPVdeconv) and to week 10 (PFS: p < 0.05 for BVpatlak, BFmax, SPVdeconv, SPVmax and PS). The relative changes in kurtosis between baseline and week 5 also had an association to OS (p < 0.005 for BVpatlak, BFmax and SPVmax; p < 0.05 for BFdeconv and SPVdeconv). The other parameters from the histogram analysis showed no definite tendencies.

Table 2.

Statistical parameters and time points that had the strongest associations to patient outcome (OS and PFS), p-values and the median survival in months (above the median; below the median) are indicated in the table below

| Baseline | Relative change from baseline to week 5 | Relative change from baseline to week 10 | ||||||

| Median | Mode | Median | Mode | Kurtosis | Median | Mode | ||

| BVdeconv | PFS | 0.018a(10.8; 5.3) | 0.328 (9.9; 5.6) | 0.023a(5.4; 10.8) | 0.001a(5.3; 10.8) | 0.589 (5.5; 9.5) | 0.035a(8.1; 10.8) | 0.052 (5.4; 10.8) |

| OS | 0.045a(35.2; 20.2) | 0.173 (35.2; 21.1) | 0.274 (19.1; 30.7) | 0.257 (20.2; 30.7) | 0.389 (28.4; 27.5) | 0.216 (24.0; 31.7) | 0.061 (20.2; 36.3) | |

| BVpatlak | PFS | 0.166 (10.8; 5.3) | 0.213 (10.8; 5.4) | 0.029a(5.3; 11.1) | <0.001a(5.3; 14.3) | 0.001a(12.0; 5.3) | 0.201 (8.1; 10.8) | 0.011a(5.4; 12.7) |

| OS | 0.161 (36.3; 27.5) | 0.021a(36.3; 21.1) | 0.051 (20.2; 53.0) | 0.011a(19.1; 53.0) | 0.004a(53.0; 14.6) | 0.792 (30.7; 28.4) | 0.042a(20.2; 36.3) | |

| BFdeconv | PFS | 0.060 (10.8; 5.4) | 0.036a(10.8; 5.4) | 0.025a(5.4; 10.8) | 0.006a(5.3; 11.1) | 0.052 (8.3; 8.1) | 0.052 (5.6; 10.8) | 0.056 (5.6; 10.8) |

| OS | 0.046a(36.3; 21.1) | 0.005a(36.3; 19.1) | 0.521 (27.9; 31.7) | 0.148 (27.5; 31.7) | 0.017a(NR; 19.1) | 0.193 (19.1; 31.7) | 0.295 (27.5; 31.7) | |

| BFmax | PFS | 0.165 (10.8; 5.3) | 0.176 (10.8; 5.4) | 0.057 (5.4; 10.8) | 0.011a(5.3; 10.8) | 0.125 (10.8; 5.6) | 0.117 (8.2; 10.8) | 0.007a(5.5; 11.1) |

| OS | 0.183 (35.2; 21.1) | 0.144 (35.2; 21.1) | 0.774 (35.2; 27.9) | 0.407 (27.5; 36.7) | 0.004a(53.0; 15.7) | 0.188 (19.1; 31.7) | 0.114 (21.1; 31.7) | |

| SPVdeconv | PFS | 0.107 (10.8; 5.3) | 0.135 (10.8; 5.6) | 0.060 (5.3; 10.8) | 0.005a(5.3; 12.0) | 0.090 (8.3; 8.2) | 0.078 (8.2; 10.8) | 0.014a(8.1; 10.8) |

| OS | 0.009a(36.3; 19.1) | 0.001a(36.3; 14.6) | 0.594 (27.5; 30.7) | 0.111 (20.2; 53.0) | 0.025a(NR; 21.1) | 0.192 (19.1; 31.7) | 0.103 (15.7; 35.2) | |

| SPVmax | PFS | 0.388 (9.5; 5.3) | 0.756 (8.3; 8.2) | 0.317 (5.6; 8.3) | 0.691 (5.5; 8.3) | 0.155 (10.8; 8.1) | 0.150 (8.2; 8.5) | 0.016a(5.4; 10.8) |

| OS | 0.516 (31.7; 24.0) | 0.343 (31.7; 21.1) | 0.607 (27.5; 28.4) | 0.925 (27.5; 28.4) | 0.001a(53.0; 15.7) | 0.375 (20.2; 30.7) | 0.091 (19.1; 31.7) | |

| PS | PFS | 0.829 (8.1; 8.3) | 0.592 (9.9; 8.2) | 0.957 (8.2; 9.9) | 0.066 (8.1; 10.9) | 0.319 (8.1; 9.9) | 0.342 (8.3; 10.8) | 0.044a(8.2; 12.0) |

| OS | 0.665 (31.7; 27.5) | 0.745 (31.7; 28.4) | 0.499 (27.9; 53.0) | 0.025a(21.1; 53.0) | 0.963 (27.9; 30.7) | 0.477 (28.4; 53.0) | 0.755 (28.4; 27.9) | |

BF, blood flow; BV, blood volume; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, permeability surface; SPV, standardized perfusion value.

ap < 0.05.

NR, not reached [more than half of the patients had not progressed (progression-free survival) or were alive (overall survival)].

When all mRCC patients are grouped regardless of treatment, BVdeconv, BVpatlak, BFdeconv and SPVdeconv have stronger associations to patient outcomes than BFmax, SPVmax and PS. Associations between dynamic contrast-enhanced CT parameters and patient outcomes were tested using Kaplan–Meier plots and log rank tests with the data divided using medians.

Using median and mode to assess the seven DCE-CT parameters BVdeconv, BVpatlak, BFdeconv, BFmax, SPVdeconv, SPVmax and PS, the strongest associations were observed between patient outcome and BVdeconv, BVpatlak and BFdeconv at baseline and during the early ontreatment period (relative changes to weeks 5 and 10) (Table 2). For the relative changes in median and mode between baseline and weeks 5 and 10, PS seemed to have a negative association with patient outcome for those treated with angiogenesis inhibitors (all patients in AIS as well as those in DARENCA-1 receiving bevacizumab) and a positive association with patient outcome for those treated with immunotherapy alone.

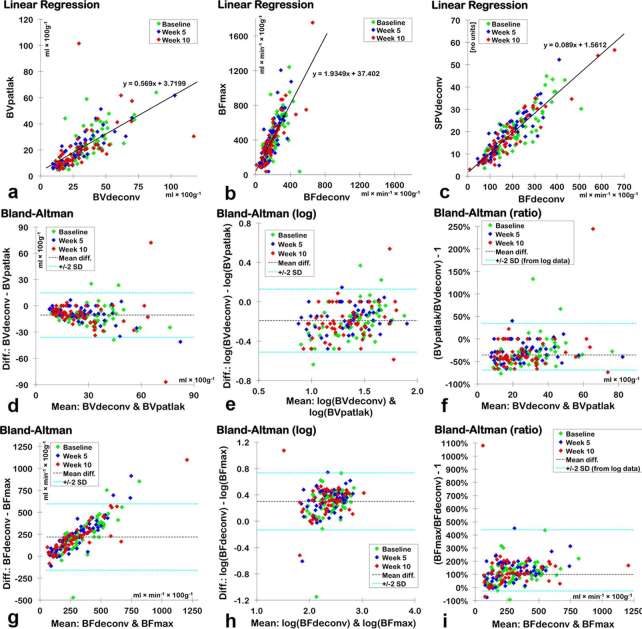

Comparison of mathematical models

The correlations between similar DCE-CT parameters derived using different mathematical models were good or excellent according to Spearman’s rank correlation tests (Table 3). Using log transformed Bland–Altman plots, we found biases showing that BVpatlak was −35.6% (medians) or −40.3% (modes) compared with BVdeconv. BFmax was +99.2% (medians) or +87.6% (modes) compared with BFdeconv. The 95% limits of agreement were very broad, especially for the BFs (Table 3 and Figure 3). Using medians, SPVdeconv was 8.9% of the numerical value of BF deconv, and SPVmax was 9.2% of the numerical value for BFmax. Using modes, the percent of the numerical value was 9.0 and 9.8%, respectively.

Table 3.

Correlations and agreements between similar DCE-CT parameters calculated using different mathematical models

| Linear regression | Spearman’s rank correlation | Bland–Altman plots of agreement | |||||

| x | y | Median or mode | Slope | rs | p-valuea | Ratio: (y/x) − 1 in percent | 95% limits of agreement (from log10 data) |

| BVdeconv | BVpatlak | Median | 0.569 | 0.815 | <0.001 | −35.6% | −69.2%; +34.6% |

| Mode | 0.755 | 0.813 | <0.001 | −40.3% | −74.8%; +41.3% | ||

| BFdeconv | BFmax | Median | 1.935 | 0.812 | <0.001 | +99.2% | −26.5%; +439.7% |

| Mode | 1.442 | 0.795 | <0.001 | +87.6% | −30.6%; +407.4% | ||

| SPVdeconv | SPVmax | Median | 2.152 | 0.866 | <0.001 | +105.2% | −2.8%; +333.1% |

| Mode | 1.739 | 0.856 | <0.001 | +90.8% | −12.6%; +316.6% | ||

| BFdeconv | SPVdeconv | Median | 0.089 | 0.895 | <0.001 | ||

| Mode | 0.090 | 0.903 | <0.001 | ||||

| BFmax | SPVmax | Median | 0.092 | 0.902 | <0.001 | ||

| Mode | 0.098 | 0.894 | <0.001 | ||||

BF, blood flow; BV, blood volume; DCE-CT, dynamic contrast-enhanced CT; SPV, standardized perfusion value.

ap < 0.05.

Spearman’s rank correlation and log transformed data were used, because the differences in the non-transformed data increased with the magnitude of the mean. For clinically meaningful values, the mean difference and 95% limits of agreement have then been back-transformed to express y as the relative difference from x. Bland–Altman plots were not made for comparisons between BFs and SPVs because of their different units.

Figure 3.

Linear regressions for medians of BVdeconv and BVpatlak (a), BFdeconv and BFmax (b) and BFdeconv and SPVdeconv (c) with lines and equations representing the best fit. Bland–Altman plots for BVdeconv and BVpatlak (d−f) and BFdeconv and BFmax (g−i). (d, g) are Bland–Altman plots with the original values. As the variability of the difference increased with the mean, the data were log10-transformed (e, h) to find reliable 95% LOA (denoted as “± 2 SD”). In (f, i), the data points, mean difference and 95% LOA were transformed back so the results could be expressed as relative differences from the x-axis parameter [as defined in the linear graphs (a, b) and in Table 3]. BF, blood flow; BV, blood volume; LOA, limits of agreement; SPV, standardized perfusion value.

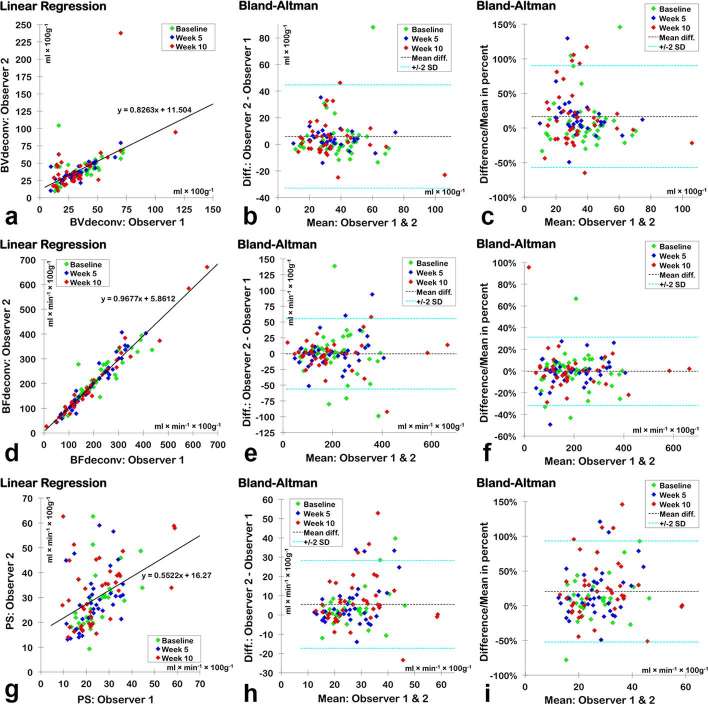

Interobserver assessments

The correlations between interobserver assessments for each of the seven DCE-CT parameters identified excellent positive correlations (r > 0.9 and p < 0.001) and good agreement (mean difference as per cent < ± 5%) for BFdeconv, BFmax, SPVdeconv and SPVmax and moderate to good positive correlations for BVdeconv and BVpatlak, where as PS (median) had a moderate positive correlation (Table 4 and Figure 4). Blood flow using medians produced the best agreement and smallest biases (BFdeconv= −0.2% and BFmax= +1.5%) of all seven DCE-CT parameters. Mode had lower correlation coefficients and larger limits of agreement than medians suggesting that medians have a better reproducibility.

Table 4.

Interobserver variation and correlation for median and mode of all seven DCE-CT parameters

| Linear regression | Pearson’s correlation | Bland–Altman plots of agreement | ||||

| Parameters | Slope | r | p-value | Mean difference (± SD) | Difference as percent (± SD) | |

| BVdeconv | Median | 0.826 | 0.580 | <0.001 | +5.88 (± 19.41) | +16.6% (± 36.8%) |

| Mode | 1.01 | 0.528 | <0.001 | +6.34 (± 23.58) | +20.3% (± 41.9%) | |

| BVpatlak | Median | 0.760 | 0.703 | <0.001 | +5.20 (± 11.39) | +19.4% (± 40.2%) |

| Mode | 0.501 | 0.506 | <0.001 | +5.43 (± 12.79) | +24.1% (± 52.3%) | |

| BFdeconv | Median | 0.968 | 0.966 | <0.001 | −0.46 (± 27.85) | −0.2% (± 15.7%) |

| Mode | 0.936 | 0.903 | <0.001 | −0.15 (± 46.16) | −0.1% (± 25.5%) | |

| BFmax | Median | 0.970 | 0.962 | <0.001 | +6.31 (± 79.01) | +1.5% (± 15.8%) |

| Mode | 0.879 | 0.938 | <0.001 | +11.18 (± 75.98) | +3.3% (± 29.7%) | |

| SPVdeconv | Median | 0.997 | 0.965 | <0.001 | −0.13 (± 2.94) | −0.7% (± 27.8%) |

| Mode | 0.997 | 0.938 | <0.001 | −0.26 (± 3.78) | −1.5% (± 33.9%) | |

| SPVmax | Median | 0.971 | 0.954 | <0.001 | +0.72 (± 8.94) | +1.7% (± 24.1%) |

| Mode | 0.899 | 0.948 | <0.001 | +0.70 (± 7.75) | +2.1% (± 27.7%) | |

| PS | Median | 0.552 | 0.438 | <0.001 | +5.49 (± 11.38) | +20.5% (± 36.4%) |

| Mode | 0.100 | 0.192 | 0.031 | +4.18 (± 25.37) | +17.8% (± 59.8%) | |

BF, blood flow; BV, blood volume; DCE-CT, dynamic contrast-enhanced CT; PS, permeability surface; SD, standard deviation; SPV, standardized perfusion value.

Difference as a percentage of the mean is found by dividing the difference with the mean and plotting this on the y-axis of the Bland–Altman plot. As the ranges and means are very different from one parameter to another, this allows for a better comparison of agreement between parameters showing that BFdeconv using medians has the best correlation and agreement and the least bias of all the parameters.

Figure 4.

Interobserver correlations using medians of BFdeconv (a−c), BVdeconv (d−f) and PS (g−i). (a, d and g) are plots of linear regression with lines and equations representing the best fit. (b, f and j) are Bland–Altman plots using the original values, while (c, f and i) express the differences as percentages of the mean, allowing a way of comparing interobserver agreement among parameters that have very different ranges. BFdeconv (f) clearly has the narrowest 95% LOA (denoted as “± 2 SD”) even although it seems to have the broadest 95% LOA when only considering the mean difference (e) as the values for BFdeconv are on average 5.5 and 7.3 times larger than those for BVdeconv and PS, respectively. BV, blood volume; LOA, limits of agreement; PS, permeability surface.

Discussion

The present study used patient outcome endpoints to identify the best functional imaging parameters in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. BVdeconv and BVpatlak both showed statistically significant associations to patient outcome and were closely correlated to each other. Interobserver correlations for BVdeconv and BVpatlak were moderate to good although their agreements displayed a bias of about 20% of the mean and 95% limits of agreement of about ± 80% of the mean. PS had agreements, which were very similar to the BVs, but had poor-to-moderate interobserver correlations. BFdeconv and SPVdeconv showed closer associations to patient outcome than BFmax and SPVmax. Interobserver agreement plots showed that BFdeconv had a smaller standard deviation (of difference as a percentage of the mean) than SPVdeconv, and BFs were also simpler as SPVs required the additional input of patient weight, contrast media volume, contrast media concentration and an iodine calibration factor. All four of the perfusion parameters had excellent interobserver correlations. Generally for correlations between mathematical models and between observers, medians had higher correlations and smaller or equal limits of agreement compared with modes suggesting that medians are more reproducible. In essence, BVdeconv, BVpatlak and BFdeconv were the best parameters for providing clinically meaningful information when patient outcome and reproducibility are taken into account. PS seemed to be treatment dependent. Before entering clinical practice, our findings should be verified in larger studies.

For renal cell carcinoma, no one has previously published studies using patient outcome endpoints to identify the best mathematical models for calculating DCE-CT parameters, whereas Koh et al11 and Lee et al13 have published studies of colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, respectively. Koh et al11 found in a study of 46 patients comparing the mathematical models conventional compartment, AATH and distributed parameters (DPs), that only extravascular extracellular volume derived using the DP model had a correlation with 5-year survival. Lee et al13 found in a study of 22 patients comparing the mathematical models Tofts-Kety, 2 compartment exchange, AATH and DP, that the extraction fraction derived using AATH was correlated to 1-year survival and also positively correlated to OS. For both studies, no other parameters were found to significantly correlate to patient outcome. As neither the extravascular extracellular volume nor the extraction fraction was available on our platform, we were unable to test these parameters in the present study.

No published studies for renal cell carcinoma examined correlations between similar DCE-CT parameters derived from different mathematical models. However, a number of studies using other tumours have examined agreements between more than one mathematical model for deriving BV and/or BF.7–11,13,14,20,21 Altogether, the agreements between the values were quite dissimilar even when the same mathematical model was used. As each mathematical model is built on certain assumptions, it follows that different types of tumours could give differing agreements if the one type of tumour conforms to the model’s assumptions while another type of tumour violates these assumptions. Differing agreements can also be owing to the differences in DCE-CT acquisition parameters and post-processing software, problems that have been highlighted in earlier studies.9,22–24 Recently, a research group has suggested a framework for comparison of five of the most commonly used kinetic models in DCE-CT and DCE MRI,15 however, a larger cooperation between vendors and between institutions is necessary to ensure the transparency required to advance research in this field.

Our study is the first to use SPVs in renal cell carcinoma and the first study comparing different mathematical models for deriving SPVs. Previous studies exploring the use of SPVs in lung, breast and colorectal cancers19,25–29 have compared DCE-CT’s SPV with FDG-PET’s SUV, while a single study30 has compared the SPV of oesophagus cancer with the SPV of skeletal muscle. Theoretically, SPVs could be used to correct for some differences in acquisition parameters including different scanners, different peak kilovolts and different contrast concentrations, but in our study using the same protocols and same equipment, SPVs offered no advantage compared with BF.

Previously, only one study has explored interobserver correlations for DCE-CT parameters in renal cell carcinoma. Reiner et al31 found excellent correlations (r > 0.90) and small mean differences between observers for BF, BV and permeability (Ktrans). We found excellent correlations for all perfusion parameters (BF and SPV), moderate/good correlations for BV and only moderate correlations for PS. Our study seemed to have larger mean differences, i.e. for BFmax, the mean difference was + 6.31 ml × min−1× 100 g−1 in our study vs 3.2 ml × min−1 × 100 g−1 in the study by Reiner et al.31 However, the range in their study31 was 29.5 to 308.3 ml × min−1 × 100 g−1, while it was 84.7 to 1753.1 ml × min−1 × 100 g−1 in our study, demonstrating that even when using similar tumours and mathematical models, data from two different research institutions analysed using software from two different vendors do not seem to be directly comparable.

For various other tumours, BF always has good or excellent interobserver correlations,10,28,32–39 while BV has mostly good or excellent correlations,10,32,33,35–40 but also some moderate interobserver correlations.28, 34 For permeability and PS, there were also mostly good and excellent interobserver correlations,28, 33,37,39 but also moderate correlations.35, 36 It was not clear for all studies whether interobserver studies were based on tumour delineation only or on a larger portion of DCE-CT analysis process, which would result in greater variation than delineation only. In addition, the bin size for the histogram data in our study could not be adjusted prior to extraction, which resulted in data that for PS and BV were spread over fewer bins and, therefore, less granular.

Study limitations were the small sample size, although the present prospective study represents one of the largest studies to date. We did a large number of statistical analyses, thus, multiple testing in combination with the small sample size could lead to unreliable results. However, as the focus of our statistical analysis was to identify trends and patterns in our data, not simply focusing on single significant p-values, we chose not to adjust our p-values for multiple testing. Another limitation is the lack of external verification using an independent test data set.

Conclusions

Patient outcome was used to identify the best functional imaging parameter in patients with mRCC. In our study, BVdeconv, BVpatlak and BFdeconv were the best parameters for providing clinically meaningful information when patient outcome and reproducibility were taken into account. PS seems to be treatment dependent. Standardization of acquisition protocols and post-processing software is necessary in order to improve the clinical utility of DCE-CT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

JRM and JT received research grants from the Memorial Foundation of Eva and Henry Fraenkel. JRM, FD and JT received research grants from the Health Research Fund of Central Denmark Region. Philips Healthcare provided the software used for the DCE-CT analysis. Roche and Novartis supported the clinical part of the study but were not involved in the translational imaging part of the study.

Contributor Information

Jill Rachel Mains, Email: jill.mains@rm.dk.

Frede Donskov, Email: frede.donskov@aarhus.rm.dk.

Erik Morre Pedersen, Email: erikpede@rm.dk.

Hans Henrik Torp Madsen, Email: hansmads@rm.dk.

Jesper Thygesen, Email: jesthy@rm.dk.

Kennet Thorup, Email: kennthor@rm.dk.

Finn Rasmussen, Email: finnrasm@rm.dk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miles KA, Lee TY, Goh V, Klotz E, Cuenod C, Bisdas S, et al. Current status and guidelines for the assessment of tumour vascular support with dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 1430–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-012-2379-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miles KA, Charnsangavej C, Lee FT, Fishman EK, Horton K, Lee TY. Application of CT in the investigation of angiogenesis in oncology. Acad Radiol 2000; 7: 840–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1076-6332(00)80632-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miles KA. Measurement of tissue perfusion by dynamic computed tomography. Br J Radiol 1991; 64: 409–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/0007-1285-64-761-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miles KA, Kelley BB. CT measurements of capillary permeability within nodal masses: a potential technique for assessing the activity of lymphoma. Br J Radiol 1997; 70: 74–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.70.829.9059299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1983; 3: 1–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.1983.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St Lawrence KS, Lee TY. An adiabatic approximation to the tissue homogeneity model for water exchange in the brain: I. Theoretical derivation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998; 18: 1365–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00004647-199812000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bisdas S, Konstantinou G, Surlan-Popovic K, Khoshneviszadeh A, Baghi M, Vogl TJ, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT of head and neck tumors. Acad Radiol 2008; 15: 1580–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2008.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djuric-Stefanovic A, Saranovic D, Masulovic D, Ivanovic A, Pesko P. Comparison between the deconvolution and maximum slope 64-MDCT perfusion analysis of the esophageal cancer: is conversion possible? Eur J Radiol 2013; 82: 1716–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goh V, Halligan S, Bartram CI. Quantitative tumor perfusion assessment with multidetector CT: are measurements from two commercial software packages interchangeable? Radiology 2007; 242: 777–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2423060279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufmann S, Horger T, Oelker A, Kloth C, Nikolaou K, Schulze M, et al. Characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) lesions using a novel CT-based volume perfusion (VPCT) technique. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 1029–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh TS, Ng QS, Thng CH, Kwek JW, Kozarski R, Goh V. Primary colorectal cancer: use of kinetic modeling of dynamic contrast-enhanced CT data to predict clinical outcome. Radiology 2013; 267: 145–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.12120186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer GM, Yaqub M, Bahce I, Smit EF, Lubberink M, Hoekstra OS, et al. CT-perfusion versus [(15)O]H2O PET in lung tumors: effects of CT-perfusion methodology. Med Phys 2013; 40: 052502: 52502. doi: https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4798560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SH, Hayano K, Zhu AX, Sahani DV, Yoshida H. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: perfusion computed tomography-based kinetic parameter as a prognostic biomarker for prediction of patient survival. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2015; 39: 687–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/RCT.0000000000000288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Elmpt W, Das M, Hüllner M, Sharifi H, Zegers K, Reymen B, et al. Characterization of tumor heterogeneity using dynamic contrast enhanced CT and FDG-PET in non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol 2013; 109: 65–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romain B, Rouet L, Ohayon D, Lucidarme O, d'Alché-Buc F, Letort V. Parameter estimation of perfusion models in dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging: a unified framework for model comparison. Med Image Anal 2017; 35: 360–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donskov F, Jensen NV, Smidt-Hansen T, Brondum L, Geertsen PF. A randomized phase II trial of interleukin-2/interferon-α plus bevacizumab versus interleukin-2/interferon-α in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): results from the Danish renal cancer group (DARENCA) study 1. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: abstr 4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mains JR, Donskov F, Pedersen EM, Madsen HH, Rasmussen F. Dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography-derived blood volume and blood flow correlate with patient outcome in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Invest Radiol 2017; 52: 103–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0000000000000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mains JR, Donskov F, Pedersen EM, Madsen HHT, Rasmussen F. Dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography as a potential biomarker in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Invest Radiol 2014; 49: 601–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0000000000000058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles KA, Griffiths MR, Fuentes MA. Standardized perfusion value: universal CT contrast enhancement scale that correlates with FDG PET in lung nodules. Radiology 2001; 220: 548–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.220.2.r01au26548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sitartchouk I, Roberts HC, Pereira AM, Bayanati H, Waddell T, Roberts TP. Computed tomography perfusion using first pass methods for lung nodule characterization. Invest Radiol 2008; 43: 349–58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181690148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibuya K, Tsushima Y, Horisoko E, Noda SE, Taketomi-Takahashi A, Ohno T, et al. Blood flow change quantification in cervical cancer before and during radiation therapy using perfusion CT. J Radiat Res 2011; 52: 804–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1269/jrr.11079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Driscoll B, Keller H, Jaffray D, Coolens C. Development of a dynamic quality assurance testing protocol for multisite clinical trial DCE-CT accreditation. Med Phys 2013; 40: 081906: 81906. doi: https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4812429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goh V, Shastry M, Engledow A, Reston J, Wellsted DM, Peck J, et al. Commercial software upgrades may significantly alter perfusion CT parameter values in colorectal cancer. Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 744–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-010-1967-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzei MA, Squitieri NC, Sani E, Guerrini S, Imbriaco G, Di Lucia D, et al. Differences in perfusion CT parameter values with commercial software upgrades: a preliminary report about algorithm consistency and stability. Acta Radiol 2013; 54: 805–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185113484643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shastry M, Miles KA, Win T, Janes SM, Endozo R, Meagher M, et al. Integrated 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography to phenotype non-small cell lung carcinoma. Mol Imaging 2012; 11: 353–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groves AM, Wishart GC, Shastry M, Moyle P, Iddles S, Britton P, et al. Metabolic-flow relationships in primary breast cancer: feasibility of combined PET/dynamic contrast-enhanced CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009; 36: 416–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-0948-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miles KA. Functional CT imaging in oncology. Eur Radiol 2003; 13(Suppl 5): 134–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-003-2108-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goh V, Shastry M, Engledow A, Kozarski R, Peck J, Endozo R, et al. Integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT and perfusion CT of primary colorectal cancer: effect of inter- and intraobserver agreement on metabolic-vascular parameters. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199: 1003–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.11.7823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles KA, Griffiths MR, Keith CJ. Blood flow-metabolic relationships are dependent on tumour size in non-small cell lung cancer: a study using quantitative contrast-enhanced computer tomography and positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2006; 33: 22–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-005-1932-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Djuric-Stefanovic A, Saranovic D, Sobic-Saranovic D, Masulovic D, Artiko V. Standardized perfusion value of the esophageal carcinoma and its correlation with quantitative CT perfusion parameter values. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 350–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiner CS, Goetti R, Eberli D, Klotz E, Boss A, Pfammatter T, et al. CT perfusion of renal cell carcinoma: impact of volume coverage on quantitative analysis. Invest Radiol 2012; 47: 33–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0b013e31822598c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen TW, Yang ZG, Chen HJ, Li Y, Tang SS, Yao J, et al. Quantitative assessment of first-pass perfusion using a low-dose method at multidetector CT in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: correlation with VEGF expression. Clin Radiol 2012; 67: 746–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2011.07.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee SM, Lee HJ, Kim JI, Kang MJ, Goo JM, Park CM, et al. Adaptive 4D volume perfusion CT of lung cancer: effects of computerized motion correction and the range of volume coverage on measurement reproducibility. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 200: W603–W609. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.12.9458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauter AW, Merkle A, Schulze M, Spira D, Hetzel J, Claussen CD, et al. Intraobserver and interobserver agreement of volume perfusion CT (VPCT) measurements in patients with lung lesions. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: 2853–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.06.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petralia G, Summers P, Viotti S, Montefrancesco R, Raimondi S, Bellomi M. Quantification of variability in breath-hold perfusion CT of hepatocellular carcinoma: a step toward clinical use. Radiology 2012; 265: 448–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.12111232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petralia G, Preda L, Raimondi S, D'Andrea G, Summers P, Giugliano G, et al. Intra- and interobserver agreement and impact of arterial input selection in perfusion CT measurements performed in squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009; 30: 1107–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fraioli F, Anzidei M, Zaccagna F, Mennini ML, Serra G, Gori B, et al. Whole-tumor perfusion CT in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma treated with conventional and antiangiogenetic chemotherapy: initial experience. Radiology 2011; 259: 574–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11100600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goh V, Halligan S, Hugill JA, Bassett P, Bartram CI. Quantitative assessment of colorectal cancer perfusion using MDCT: inter- and intraobserver agreement. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185: 225–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.185.1.01850225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Q-S N, Thng CH, Lim WT, Hartono S, Thian YL, Lee PS, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Invest Radiol 2012; 47: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng QS, Goh V, Fichte H, Klotz E, Fernie P, Saunders MI, et al. Lung cancer perfusion at multi-detector row CT: reproducibility of whole tumor quantitative measurements. Radiology 2006; 239: 547–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2392050568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]