Abstract

Objectives:

This study evaluates the use of balanced steady-state free precession MRI (bSSFP-MRI) in the diagnostic work-up of patients undergoing interventional deep venous reconstruction (I-DVR). Intravenous digital subtraction angiography (IVDSA) was used as the gold-standard for comparison to assess disease extent and severity.

Methods:

A retrospective comparison of bSSFP-MRI to IVDSA was performed in all patients undergoing both examinations for treatment planning prior to I-DVR. The severity of disease in each venous segment was graded by two board-certified radiologists working independently, according to a predetermined classification system.

Results:

In total, 44 patients (225 venous segments) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. A total of 156 abnormal venous segments were diagnosed using bSSFP-MRI compared with 151 using IVDSA. The prevalence of disease was higher in the iliac and femoral segments (range, 79.6–88.6%). Overall sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio and the diagnostic ratio for bSSFP-MRI were 99.3%, 91.9%, 12.3, 0.007 and 1700, respectively.

Conclusion:

This study supports the use of non-contrast balanced SSFP-MRI in the assessment of the deep veins of the lower limb prior to I-DVR. The technique offers an accurate, fast and non-invasive alternative to IVDSA.

Advances in Knowledge:

Although balanced SSFP-MRI is commonly used in cardiac imaging, its use elsewhere is limited and its use in evaluating the deep veins prior to interventional reconstruction is not described. Our study demonstrates the usefulness of this technique in the work-up of patients awaiting interventional venous reconstruction compared with the current gold standard.

Introduction

Post-thrombotic Syndrome (PTS) is a late complication of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), usually occurring within 1–2 years and affecting up to 75% of patients with lower extremity DVT.1 PTS manifests with a range of features, from minor signs (stasis pigmentation, venous ectasia, mild pain and swelling) to intractable oedema, severe chronic pain and ulceration.2 Risk factors for PTS include ipsilateral DVT, obesity and inadequate anticoagulation.2 Although the pathophysiology of PTS is not completely understood, it is thought that venous obstruction and valve incompetence to varying degrees are important factors that lead to the development of chronic venous hypertension.2

When PTS is attributed to venous obstruction, deep venous reconstruction either by open surgical bypass procedures or increasingly by endovascular (interventional deep venous reconstruction, I-DVR) techniques can lead to relief of venous hypertension.3 I-DVR is less invasive, associated with lower morbidity and allows earlier ambulation when compared with surgical bypass.4

Given the increase in importance of I-DVR procedures, accurate preprocedural assessment is essential, both to qualify and quantify pathology. Specifically, preprocedural imaging enables the operator to assess whether a patient is amenable to I-DVR; plan access (e.g. femoral, jugular or both); select balloon or stent diameters and lengths. Duplex ultrasound is a useful non-invasive first-line imaging modality used to diagnose infrainguinal venous pathology. However, the accuracy of venous duplex in the visualization of pelvic and abdominal veins is markedly reduced, particularly when body habitus or overlying bowel gas impair views.5

While conventional digital subtraction ascending and descending venography is generally accepted as the reference standard, it is an invasive procedure, carries the risks of ionizing radiation, allergy and nephrotoxicity to iodinated contrast and is associated with an overall complication rate of 2–5%.6 Contrast-enhanced CT and MR venography have become well established in venous evaluation. They also, however, involve venous cannulation, the administration of contrast media and the risk of adverse reaction and nephrotoxicity. In the case of MRI, there is a small risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis following gadolinium administration in the context of renal dysfunction. In the case of CT, there is also the associated risk of malignancy induced by ionizing radiation, this is especially a consideration for patients with venous disease as they frequently present early in adulthood.7

Balanced steady-state free procession MRI (bSSFP-MRI) is widely used for cardiac imaging, the inherent signal intensity of flowing blood is exploited to contrast with dark myocardium without the need for intravenous contrast.8 More recently, interest has grown in bSSFP-MRI for extracardiac vascular assessment, for example in the evaluation of arteries of the head and neck,9 superficial femoral arteries,10 portal veins11 and the deep veins of the lower limbs.12–14 bSSFP-MRI venography is advantageous because it is quick, does not require intravenous contrast and is not susceptible to flow artefact arising from slow moving blood. Additionally, in the current economic climate, not using a contrast agent could result in significant cost saving.15

In this study, we examine the potential of bSSFP-MRI to diagnose venous outflow obstruction in the setting of established PTS and to help tailor an interventional treatment strategy. The specific purpose of this study is to compare the performance of bSSFP-MRI in diagnosing the location and severity of venous disease compared with intravenous digital subtraction angiography (IVDSA), the current gold-standard.

Methods AND MATERIALS

All patients who underwent bSSFP-MRI and IVDSA between December 2012 and June 2015 at the authors’ institution (Department of Radiology, Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust) as work-up prior to an I-DVR procedure were included in the study. Patients imaged with a single modality or other modalities not including bSSFP-MRI or IVDSA were excluded from the study. Patients were identified following a query of the radiology information system (RIS). Institutional review board approval was gained.

All MRI was performed on a 1.5 T Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) MRI scanner. Patients were imaged lying supine without thigh compression. The scanning parameters are summarized in Table 1. The mean acquisition time for the MRI scan was 15 min (range, 10–18 min).

Table 1.

Balanced steady-state free precession MRI imaging protocol summarized

| Scanner | Siemens 1.5 T Aera and Avanto |

|---|---|

| Acquisition parameters | 4 blocks to cover from diaphragm to knees |

| 40 slices per block 4 mm slice thickness | |

| 0% gap | |

| TR 4 ms, TE 1.77 ms | |

| Phase 65% anteroposterior | |

| Flip angle 47 | |

| FOV 400 | |

| Base resolution 256 × 256 | |

| Bandwidth 454 Hz | |

| Multimodal sequential | |

| Elliptical filter | |

| GRAPPA 2 |

TE, echo time; TR, repetition time.

IVDSA was performed on a Siemens Artis Zee (Erlangen, Germany) at an exposure rate of 1 frame per second following ultrasound-guided access of the ipsilateral popliteal or femoral vein. Patients were positioned prone for popliteal access, supine for femoral vein access; thigh compression was not used. Ascending subtraction venography included standard anteroposterior acquisitions. Additional ipsilateral and contralateral oblique projections to image the profunda femoris and external iliac venous segments were acquired as deemed necessary on a case-by-case basis. Either iohexol (omnipaque 350) or iodixanol (visipaque 320) was used as the contrast agent, the total injected volume ranged from 30 to 50 ml.

Veins were divided into segments for analysis as follows: inferior vena cava (IVC), common iliac vein (CIV), external iliac vein (EIV), common femoral vein (CFV), superficial femoral vein (SFV), profunda femoral vein (PFV) and popliteal vein (PV). The infrapopliteal veins were not assessed as they are of lesser importance in planning endovascular reconstruction for patients with iliofemoral disease. Patients with an incomplete data set (e.g. missing vein segment, technically inadequate imaging) were excluded from the study.

Two consultant interventional radiologists with more than 3 years experience assessed anonymized MRI and IVDSA data sets. The image analysis was performed on a dedicated Centricity GE PACS workstation (GE Medical Systems Ltd, Hatfield, UK). In order to minimize bias, the radiologists evaluated the images from each modality individually and on separate occasions. Furthermore, the image assessment exercise was spread out over a period of several weeks. The venous segments were classified as either normal or abnormal. A consensus was achieved in cases where there was disagreement between assessors. Abnormal segments were further described as >50% stenosis, post-thrombotic webs or acute thrombosis in order to facilitate data analysis. The degree of stenosis was evaluated by comparison to the contralateral side if normal; in case of bilateral abnormality, stenosis was quantified by comparison to the calibre of the nearest patent vein segment. Associated findings such as mural thickening or venous collaterals were used to differentiate between acute and chronic occlusions, for example, but were not entered into the analysis per se.

The data was analysed using descriptive statistics and standard metrics of diagnostic test performance. Counts and percentages were used for all quantitative variables whereas continuous variables were expressed as median or mean and standard error (SE) if determined to originate from normal distributions. Diagnostic performance of bSSFP-MRI was evaluated by calculating the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR−) and the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) using IVDSA as the reference test. Likelihood ratios are powerful measures of diagnostic accuracy and are extremely useful for the comparison of competing diagnostic strategies that may inform clinical decision-making. Likelihood ratios above 10 and below 0.1 are considered to provide strong evidence to rule in or rule out diagnoses, respectively.16 Furthermore, they can be used to calculate DOR (equal to LR+/LR−) as a single indicator of overall diagnostic test performance. The value of DOR ranges from 0 to ∞, with higher values indicating better discriminatory test performance.17 Patency of venous segments was analysed on the 50% threshold. All analyses were performed with the Statsdirect statistical software package (v. 2.7.9, Statsdirect Ltd, Cheshire, UK).

Results

Study population

44 patients (225 venous segments) met the inclusion criteria in total. Baseline demographics of the included patients are summarized in Table 2. Mean patient age was 41 years (range 18–66 years) and all had a documented history of previous DVT. Abnormal venous segments were found on the left in 31 patients and on the right in 13 patients. A total of 156 abnormal venous segments were diagnosed using bSSFP-MRI, compared with 151 using IVDSA (Table 3). Overall disease prevalence was 67.1%, the burden of prevalence was greatest in the CIV (88.6%), EIV (79.6%), CFV (79.6%) and SFV (75.9%). Disease prevalence in the PFV was 53.9%, IVC 25.7% and PV 25.0% (Table 3).

Table 2.

The demographics of the patients meeting the inclusion criteria

| Demographic | Value |

|---|---|

| No of patients | 44 |

| Age | Mean age 41 years (range 18–66 years) |

| Sex | 28 female, 16 male |

| No of venous segments | 225 |

| History of provoked/unprovoked DVT | 27/17 |

| Factor provoking DVT | Antiphospholipid syndrome (6) Factor V Leiden (5) Protein-S deficiency (2) Behcet disease (1) Retroperitoneal fibrosis (4) May-Thurner syndrome (3) Pregnancy (3) Post-operative (2) Long-haul flight (1) |

DVT, deep vein thrombosis.

Table 3.

Overall abnormalities demonstrated on IVDSA and bSSFP-MRI

| Abnormal IVDSA | Abnormal bSSFP-MRI | |

|---|---|---|

| IVC (n = 35) | 9 (25.7%) | 9 (25.7%) |

| CIV (n = 44) | 39 (88.6%) | 39 (88.6%) |

| EIV (n = 44) | 35 (79.5%) | 37 (84.1%) |

| CFV (n = 44) | 35 (79.5%) | 36 (81.8%) |

| SFV (n = 29) | 22 (75.9%) | 23 (79.3%) |

| PFV (n = 13) | 7 (53.8%) | 6 (46.2%) |

| PV (n = 16) | 4 (25%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Total (n = 225) | 151 (67.1%) | 156 (69.3) |

bSSFP-MRI, balanced steady-state free procession MRI; CIV, common iliac vein; CFV, common femoral vein; EIV, external iliac vein; IVC, inferior vena cava; IVDSA, intravenous digital subtraction angiography; PFV, profunda femoral vein; PV, popliteal vein; SFV, superficial femoral vein.

Diagnostic accuracy

The majority of abnormal venous segments were described as being a stenosis >50% on both IVDSA and bSSFP-MRI (Table 4). Post-thrombotic webs were more commonly diagnosed on bSSFP-MRI (39 segments) than on IVDSA (25 segments). Overall sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio and the diagnostic ratio for bSSFP-MRI were 99.3%, 91.9%, 12.3, 0.007 and 1700, respectively. Sensitivity was 100% in the iliac and femoral venous segments where the disease was most prevalent. Specificity varied, but was higher in the IVC, CIV and CFV segments and slightly lower in the EIV and SFV segments. A summary of all diagnostic accuracy statistics with corresponding confidence intervals on a segment basis are detailed in Table 5.

Table 4.

Results table demonstrating the distribution of abnormalities in each venous segment on IV-DSA and bSSFP-MRI

| >50% stenosis | Post-thrombotic webs | Acute thrombosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVDSA | bSSFP-MRI | IVDSA | bSSFP-MRI | IVDSA | bSSFP-MRI | |

| IVC | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CIV | 36 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| EIV | 28 | 28 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| CFV | 16 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 5 | 5 |

| SFV | 13 | 11 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 |

| PFV | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| PV | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

bSSFP-MRI, balanced steady-state free procession MRI; CIV, common iliac vein; CFV, common femoral vein; EIV, external iliac vein; IVC, inferior vena cava; IVDSA, intravenous digital subtraction angiography; PFV, profunda femoral vein; PV, popliteal vein; SFV, superficial femoral vein.

Table 5.

Summary of diagnostic test statistics (95% confidence intervals)

| Anatomy | Segments (n) | Prevalence | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR(+) | LR(–) | DOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVC | 35 | 25.7% (12.5–43.3) | 100.0% (66.4–100.0) | 100.0% (86.8–100.0) | * (7.3–∞) | * (0.00–0.31) | * (27.3–∞) |

| CIV | 44 | 88.6% (75.4–96.2) | 100.0% (91.0–100.0) | 100.0% (47.8–100.0) | * (2.3–∞) | * (0.00–0.10) | * (20.8–∞) |

| EIV | 44 | 79.6% (64.7–90.2) | 100.0% (90.0–100.0) | 77.8% (40.0–97.2) | 4.5 (1.8–15.6) | * (0.00–0.13) | * (12.3–∞) |

| CFV | 44 | 79.6% (64.7–90.2) | 100.0% (90.0–100.0) | 88.9% (51.8–99.7) | 9.0 (2.3–49.6) | * (0.00–0.11) | * (19.8–∞) |

| SFV | 29 | 75.9% (56.5–89.7) | 100.0% (84.6–100.0) | 85.7% (42.1–99.6) | 7.0 (1.9–38.1) | * (0.00–0.18) | * (8.69–∞) |

| PFV | 13 | 53.9% (25.1–80.8) | 85.7% (42.1–99.6) | 100.0% (54.1–100.0) | * (2.07–∞) | 0.14 (0.03–0.61) | * (2.10–∞) |

| PV | 16 | 25.0% (7.3–52.4) | 100.0% (39.8–100.0) | 83.3% (51.6–97.9) | 6.0 (1.6–19.4) | * (0.00–0.61) | * (1.61–∞) |

| All segments | 225 | 67.1% (60.6–73.2) | 99.3% (96.4–99.9) | 91.9% (83.2–96.9) | 12.3 (5.9–26.4) | 0.007 (0.001–0.04) | 1,700 (201–68,449) |

CIV, common iliac vein; CFV, common femoral vein; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; EIV, external iliac vein; IVC, inferior vena cava; PFV, profunda femoral vein; PV, popliteal vein; SFV, superficial femoral vein.

The value of DOR ranges from 0 to ∞, with higher values indicating better discriminatory test performance.

Discussion

Compared to the gold-standard IVDSA, this study demonstrates bSSFP-MRI overall to be both a sensitive (99%) and specific (92%) tool for diagnosing venous outflow disease in the setting of previous thromboembolic disease (Figure 1). Compared with the gold-standard, bSSFP-MRI is also able to reliably differentiate findings associated with chronic occlusion (e.g. stenosis and webs) from those associated with acute occlusion. The sensitivity of bSSFP-MRI was in excess of 95% for all venous segments with the exception of the PFV (85.7%). This may be attributed to undercalling stenoses > 50% on MRI in three patients (Table 4), probably owing to the small calibre of the affected segment. Duplex ultrasound complements the assessment of the smaller infrainguinal vein segments.5 The specificity of bSSFP-MRI was in excess of 85% for the IVC, CIV, CFV and PFV. Specificity was slightly reduced for the EIV (78%), owing to overcalling post-thrombotic webs in two patients (Table 4). Post-thrombotic webs were also overcalled in the SFV (two patients) leading to a specificity of 86%. In addition to the diagnostic accuracy described above, bSSFP-MRI proved to be a safe and quick examination, with a mean acquisition time of 15 min and no adverse events. Vessel tortuosity may also affect diagnostic accuracy, however, the bSSFP-MRI does not suffer from the signal degradation seen in flow dependent techniques like time of flight magnetic resonance angiography.

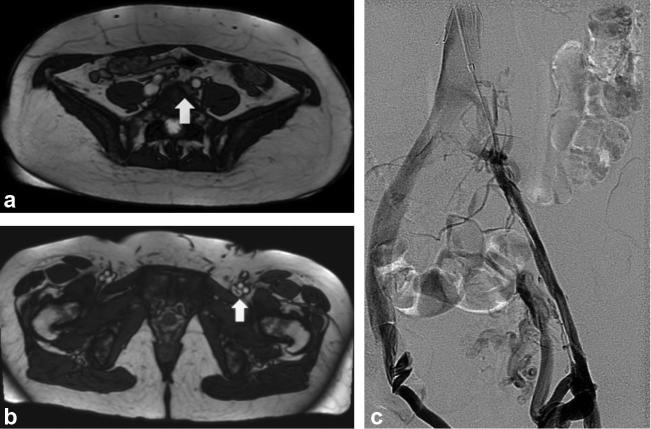

Figure 1.

(a) bSSFP-MRI image at the confluence of the CIVs demonstrating high grade compression (white arrow) of the left CIV. (b) bSSFP-MRI image at the level of the lower pelvis demonstrates high grade chronic stenosis/post thrombotic webs of the left external iliac vein and dilated pelvic collateral vein. (c) IVDSA image illustrating the high grade compression of the left CIV and stenosis of the left external iliac vein. bSSFP-MRI, balanced steady-state free procession MRI; CIV, common iliac veins; IVDSA, intravenous digital subtraction angiography.

Previous studies have looked at the accuracy of non-contrast MRI venography in the diagnosis of acute deep vein thrombosis using two-dimensional time-of-flight MR venography (TOF-MRV)18 and bSSFP-MRI. Dupas et al19 compared TOF imaging with both IVDSA and duplex ultrasound. Similarly encouraging results for non-contrast MRI venography were reported, with 100% sensitivity and 98.5% specificity (owing to two false-positives) compared with IVDSA. In comparison with TOF-MRV, the technique we have used, by virtue of being a balanced steady-state acquisition, is able to utilize the inherent high signal of blood within vessels. BSSFP-MRI has also proven to be accurate in the diagnosis of acute deep vein thrombosis.9,12 The focus of this manuscript is to validate the use of bSSFP-MRI in the setting of chronic thromboembolic disease in patients with established PTS.

Balanced SSFP-MRI is less sensitive to artefact arising from flow variation compared with TOF-MRV, CE-MRV and CT venography. It is especially important to use an imaging technique that is not flow-dependent when imaging the veins since flow may vary considerably during image acquisition (e.g. with respiration). Furthermore, data acquired from flow dependent techniques with the patient positioned supine cannot represent the flow dynamics that would be observed under normal physiological conditions. A distinct advantage of MRI over CT and conventional venography is the lack of ionizing radiation, this is a special consideration for the cohort of patients with venous disease who are typically young at first presentation.

The axial stacked bSSFP-MRI technique that we employ is a fast and robust type of gradient-echo sequence, in which longitudinal and transverse magnetization are kept constant with each cycle. A complete explanation of the bSSFP-physics is beyond the scope of this discussion. In brief, when the same sequence of radiofrequency excitations and relaxation is repeated, a steady-state forms in which the magnetization at some point in the sequence is constant from one repetition to the next, such that a balance is achieved in which both longitudinal and transverse magnetization reach a non-zero steady-state condition.20 Shorter repetition time (TR) and, therefore, shorter imaging times can be achieved with steady-state sequences. With short TR and echo time (TE), tissues with long T2 relaxation times, including blood, are bright, and it is this feature that enables imaging of blood vessels without contrast agent use.

The advantages of steady-state sequences, particularly over the older non-contrast time-of-flight and phase contrast sequences, include better signal-to-noise and contrast-to-noise ratios, faster acquisition speeds and, as previously stated is independent of flow. This makes it possible to examine large anatomical regions, such as the entire abdomen, within single breathhold acquisitions. This speed advantage also minimizes motion artefacts from respiration and peristalsis, and is especially useful in patients who have difficulty holding their breath.

When reading the bSSFP-MRI data, the femoral and profunda vein confluence with the CFV is closely inspected. In the presence of CIV/EIV disease and a normal CFV, an entirely endovascular treatment is most likely to be adopted. However, if there is common femoral/femoral/profunda vein disease, adjunctive endophlebectomy with or without formation of an arteriovenous fistula may be considered.4 The characterization of thrombus age is of clinical relevance especially when considering catheter directed thrombolysis as part of a treatment strategy. Previous studies have demonstrated that there is increased enhancement of the vessel wall adjacent to subacute thrombus.21 Anecdotal accounts suggest that bSSFP-MRI imaging may also help differentiate acute from subacute thrombus, by virtue of its T2 characteristics.10

Balanced SSFP-MRI is not without limitations, and remains relatively contraindicated in patients with ferromagnetic implants and those with claustrophobia and extreme obesity. False-positive findings can result from artefacts related to adjacent metallic objects, low bandwidth or large slice thickness (Figure 2). Slice thickness was set to 4 mm for image acquisition in this study, this relatively large thickness could have led to inaccuracy particularly in vessels of small calibre or short occluded segments. Another potential pitfall relates to the use of partial Fourier technique during image acquisition.22 Use of partial Fourier reduces data acquisition time by only acquiring part of the k-space data during each cycle. However, setting this value too low (i.e. below 6/8) can result in significant artefact that would render the acquired image non-diagnostic (Figure 3). Resetting the partial Fourier to at least 6/8 or not using this technique would ensure diagnostic image acquisition was achieved albeit with slightly increased imaging times (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

(a) bSSFP-MRI image at the level of the femoral heads. The left CFV was graded as >50% stenosis, a false-positive compared with the gold-standard. (b) IVDSA image for the same patient shows a normal appearance of the left iliac and distal femoral veins. bSSFP-MRI, balanced steady-state free procession MRI; CFV, common femoral vein; IVDSA, intravenous digital subtraction angiography.

Figure 3.

(a) bSSFP-MRI image of the IVC with partial Fourier set at 5/8 resulted in marked artefact of the IVC and small bowel. (b) When the partial Fourier was reset to 7/8, diagnostic imaging was achieved. bSSFP-MRI, balanced steady-state free procession MRI; IVC, inferior vena cava; IVDSA, intravenous digital subtraction angiography.

The retrospective nature of this study is also a limiting factor and may have led to a selection bias.

Conclusion

This study supports the use of non-contrast balanced SSFP-MRI in the assessment of the deep veins of the lower limb prior to I-DVR. The extent and location of disease involvement can be mapped with accuracy compared with the gold-standard and it is now part of our routine work-up prior to I-DVR.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank John Spence (Radiographer), Anne Frow (Radiographer) and Dawn Robinson (Radiographer) for their help and guidance in preparing this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Vincent G Helyar, Email: vincent.helyar@gmail.com.

Yuri Gupta, Email: yurikg@gmail.com.

Lyndall Blakeway, Email: lyndall.blakeway@gstt.nhs.uk.

Geoff Charles-Edwards, Email: geoff.charles-edwards@gstt.nhs.uk.

Konstantinos Katsanos, Email: katsanos@med.upatras.gr.

Narayan Karunanithy, Email: narayan.karunanithy@gstt.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Prandoni P, Kahn SR. Post-thrombotic syndrome: prevalence, prognostication and need for progress. Br J Haematol 2009; 145: 286–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn SR, Ginsberg JS. Relationship between deep venous thrombosis and the postthrombotic syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosales A, Sandbaek G, Jørgensen JJ. Stenting for chronic post-thrombotic vena cava and iliofemoral venous occlusions: mid-term patency and clinical outcome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 40: 234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna AK, Singh S. Postthrombotic syndrome: surgical possibilities. Thrombosis 2010; 2012: 520604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodacre S, Sampson F, Thomas S, van Beek E, Sutton A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis. BMC Med Imaging 2005; 5: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bettmann MA, Robbins A, Braun SD, Wetzner S, Dunnick NR, Finkelstein J, et al. Contrast venography of the leg: diagnostic efficacy, tolerance, and complication rates with ionic and nonionic contrast media. Radiology 1987; 165: 113–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, Kim KP, Mahesh M, Gould R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 2078–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treitl KM, Treitl M, Kooijman-Kurfuerst H, Kammer NN, Coppenrath E, Suderland E, et al. Three-dimensional black-blood T1-weighted turbo spin-echo techniques for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis in comparison with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: a pilot study. Invest Radiol 2015; 50: 401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindquist CM, Karlicki F, Lawrence P, Strzelczyk J, Pawlyshyn N, Kirkpatrick ID. Utility of balanced steady-state free precession MR venography in the diagnosis of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 194: 1357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedrosa I, Morrin M, Oleaga L, Baptista J, Rofsky NM. Is true FISP imaging reliable in the evaluation of venous thrombosis? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185: 1632–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith CS, Sheehy N, McEniff N, Keogan MT. Magnetic resonance portal venography: use of fast-acquisition true FISP imaging in the detection of portal vein thrombosis. Clin Radiol 2007; 62: 1180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantwell CP, Cradock A, Bruzzi J, Fitzpatrick P, Eustace S, Murray JG. MR venography with true fast imaging with steady-state precession for suspected lower-limb deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006; 17(11 Pt 1): 1763–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chavhan GB, Babyn PS, Jankharia BG, Cheng HL, Shroff MM. Steady-state MR imaging sequences: physics, classification, and clinical applications. Radiographics 2008; 28: 1147–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Graaf R, Arnoldussen C, Wittens CH. Stenting for chronic venous obstructions a new era. Phlebology 2013; 28(Suppl 1): 117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earls JP, Ho VB, Foo TK, Castillo E, Flamm SD. Cardiac MRI: recent progress and continued challenges. J Magn Reson Imaging 2002; 16: 111–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Diagnostic tests 4: likelihood ratios. BMJ 2004; 329: 168–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glas AS, Lijmer JG, Prins MH, Bonsel GJ, Bossuyt PM. The diagnostic odds ratio: a single indicator of test performance. J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56: 1129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakurai K, Miura T, Sagisaka T, Hattori M, Matsukawa N, Mase M, et al. Evaluation of luminal and vessel wall abnormalities in subacute and other stages of intracranial vertebrobasilar artery dissections using the volume isotropic turbo-spin-echo acquisition (VISTA) sequence: a preliminary study. Journal of Neuroradiology 2013; 40: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupas B, el Kouri D, Curtet C, Peltier P, de Faucal P, Planchon B, et al. Angiomagnetic resonance imaging of iliofemorocaval venous thrombosis. Lancet 1995; 346: 17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z, Fan Z, Carroll TJ, Chung Y, Weale P, Jerecic R, et al. Three-dimensional T2-weighted MRI of the human femoral arterial vessel wall at 3.0 Tesla. Invest Radiol 2009; 44: 619–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Froehlich JB, Prince MR, Greenfield LJ, Downing LJ, Shah NL, Wakefield TW. "Bull's-eye" sign on gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance venography determines thrombus presence and age: a preliminary study. J Vasc Surg 1997; 26: 809–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGibney G, Smith MR, Nichols ST, Crawley A. Quantitative evaluation of several partial Fourier reconstruction algorithms used in MRI. Magn Reson Med 1993; 30: 51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]