Abstract

Monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) is the principle enzyme for metabolizing endogenous cannabinoid ligand, 2-arachidonoyglycerol (2-AG). Blockade of MAGL increases 2-AG levels, resulting in subsequent activation of the endocannabinoid system, and has emerged as a novel therapeutic strategy to treat drug addiction, inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Herein we report a new series of MAGL inhibitors, which were radiolabeled by site-specific labeling technologies, including 11C-carbonylation and spirocyclic iodonium ylide (SCIDY) radiofluorination. The lead compound [11C]10 (MAGL-0519) demonstrated high specific binding and selectivity in vitro and in vivo. We also observed unexpected washout kinetics with these irreversible radiotracers, in which in vivo evidence for turnover of the covalent residue was unveiled between MAGL and azetidine carboxylates. This work may lead to new directions for drug discovery and PET tracer development based on azetidine carboxylate inhibitor scaffold.

Keywords: monoacylglycerol lipase, MAGL, positron emission tomography, site-specific labeling, carbon-11, fluorine-18

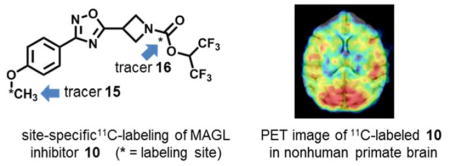

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The endocannabinoid system (eCB) is a lipid signaling network throughout the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system, which consists of two G-protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, and their corresponding ligands, anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoyglycerol (2-AG).1–5 Studies have shown that the eCB dysfunction is involved in a wide spectrum of neuropathological disorders, such as obesity, immunological dysfunction, metabolic syndromes, psychiatric conditions and neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.6–8 Early efforts towards pharmacotherapies for eCB dysfunction have been focused on direct CB1 modulation, and this approach has generated several favorable results. For example, CB1 agonism has been demonstrated to exert analgesic properties,9–11 while CB1 antagonism has reduced the risks of type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease.12–16 However, a series of adverse effects, including damage to cognition and motor function as well as abuse liability are also the result of this direct CB1 intervention, thereby hindering their application as therapeutic agents.17, 18 As endogenous ligands of eCB, AEA and 2-AG are biosynthesized and released “on request” from membrane lipid precursors in vivo and are primarily deactivated through hydrolysis catalyzed by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH, for AEA),19–21 and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL, for 2-AG).22, 23 In particular, blockage of MAGL gives rise to increased 2-AG levels, thus enhancing endocannabinoid signaling.24 MAGL inhibition also reduces levels of arachidonic acid (AA), a pain and inflammation-inducing prostaglandin precursor, and provides protection against neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases.25–29 Therefore, MAGL-based pharmacotherapy may provide an alternative and effective approach30 to stimulate eCB and beneficial treatment in pain, anxiety, inflammation, neurodegeneration and cancer,29, 31–34 without significant adverse effects, for example, mobility and cognition associated with direct CB1 modulations.4, 25, 35

Positron emission tomography (PET), a noninvasive molecular imaging modality, is ideal for quantifying eCB activity and density in vivo under normal and disease conditions with minimal perturbation of the biological state.36–39 PET also enables the study of pharmacokinetic profiles in vivo, including uptake, distribution and clearance via use of isotopologues of lead compounds that target the eCB pathway. In contrast to FAAH PET tracers that have advanced to clinical PET research imaging studies, i.e., [11C]CURB40 and [11C]MK-3168,41, 42 the development of MAGL-targeting PET tracers is still in its infancy. In recent years, considerable efforts have been implemented to radiolabeled MAGL inhibitors, including [11C]JZL184 and [11C]JJKK-048.43 However, these compounds exhibit insufficient brain uptake and failed to advance PET imaging studies in vivo. To the best of our knowledge, only two potential MAGL PET tracers, namely [11C]SAR12730344–46 and [11C]MA-PB-147 have been advanced to PET imaging studies in higher species (nonhuman primates; NHPs). As a result, unmet need of MAGL-specific PET tracers for human use, combined with therapeutic potential of MAGL-modulating pharmacotherapy provides a strong stimulus to advance PET tracer development for this target.

As part of our ongoing interest in the development of MAGL-targeting PET tracers,44, 46, 48 we explore a new class of MAGL inhibitors bearing azetidine scaffold, a privileged structure not only frequently used in drug discovery49–51 but also demonstrated as an effective way to reduce lipophilicity in recent MAGL therapeutics.52 Herein we describe our medicinal chemistry efforts to identify and synthesize a small array of azetidinyl carboxylate MAGL inhibitors that are amenable for radiolabeling with carbon-11 or fluorine-18. Preliminary pharmacological evaluation and physiochemical properties of these molecules were determined to select the most promising MAGL inhibitor 10 (MAGL-0519) for further in vivo evaluation by PET. Utilizing site-specific 11C- and 18F-labeling strategies, we were able to not only evaluate brain permeability and specificity of radiolabeled compounds, but also evaluate in vivo binding kinetics in rodents and NHPs by PET, to shed light on designed azetidinyl carboxylate-based MAGL inhibitors and PET tracers.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry

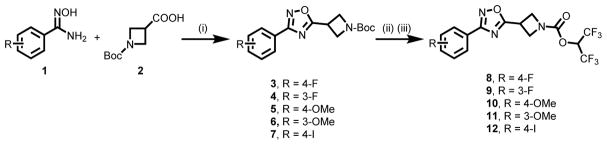

A set of azetidinyl carbamates 8-11 and their corresponding labeling precursors were designed with special emphasis on reduced lipophilicity52 and suitability for radiolabeling with carbon-11 or fluorine-18. As summarized in Scheme 1, condensation of substituted N′-hydroxybenzimidamide 1 and Boc-protected amino acid 2 triggered by HBTU successfully afforded desired oxadiazoles 3-6 in excellent yields (92–99%) by minor modifications of reported procedures.53 The hexafluoropropanoxy leaving moiety was introduced to the oxadiazoles 3-6 to form candidate MAGL inhibitor 8-11 in 63–85% yields following our previously reported strategy.46 The procedure entailed deprotection of the Boc group with trifluoroacetic acid followed by 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate mediated coupling of the corresponding secondary amine with 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) in the presence of pyridine and DMAP. The iodinated compound 12 was also synthesized in 69% yield using analogous procedure, which is designed for 18F-radiolabeling (see radiochemistry section). In brief, the synthesis of lead compounds 8-11 was achieved efficiently in three steps from commercially available 1 and 2 with overall yields of 62–80%.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of MAGL inhibitor 8-11. Conditions: (i) Et3N, HBTU, 100 °C, DMF, 5 h, 94% yield for 3; 98% yield for 4; 92% yield for 5; 99% yield for 6; 94% yield for 7; (ii) TFA, DCM, rt, overnight; (iii) 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropanol, 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate, pyridine, DMAP, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C-rt, overnight, 85% yield for 8 over two steps; 63% yield for 9; 81% yield for 10; 65% yield for 11; 73% yield for 12. HBTU = O-benzotriazol-1-yl-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate; DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide; DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine; DCM = dichloromethane.

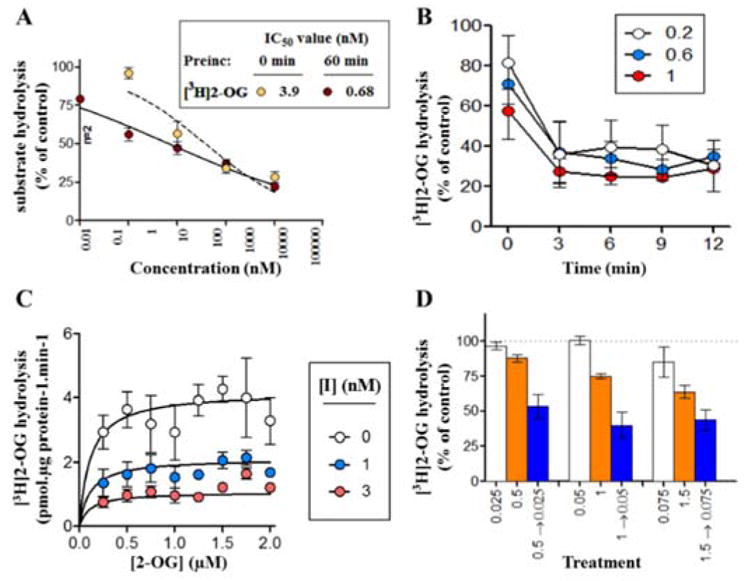

Pharmacology and physicochemical properties

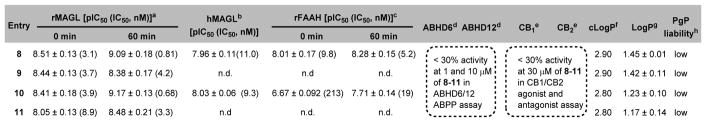

The ability of candidate compounds 8-11 to inhibit MAGL hydrolysis of tritiated 2-AG analog [3H]2-oleoylglycerol ([3H]2-OG) was determined at 0 or 60 min pre-incubation time using our previously reported protocol (Figure 1 and Figure S1, supporting information, SI).54 In particular, the inhibitory properties of the most potent MAGL inhibitor 10 were thoroughly profiled, including (i) excellent binding affinity towards MAGL (Figure 1A, IC50 = 3.9 nM without pre-incubation; 0.68 nM with 60 min of pre-incubation); (ii) time-dependent inhibition at the tested concentrations of inhibitor 10 (0.2, 0.6, and 1 nM) of 10 (Figure 1B); (iii) apparent non-competitive inhibition (Ki = 1.03 nM) of [3H]2-OG hydrolysis (Figure 1C), presumably due to covalent interaction occurring even during the short incubation time used; and (iv) irreversible binding mechanism as evidenced by dilution experiments (Figure 1D) and time course studies by activity based protein profiling (ABPP)55 assay (Figure S2, SI). As shown in Table 1, the two most potent compounds 8 and 10 were further screened in human recombinant MAGL (hMAGL) assay (Figure S3, SI) and FAAH [3H]AEA hydrolysis binding assay (Figure S4, SI). While both compounds showed excellent inhibition with IC50 values of 8 (13.4 nM) and 10 (12.7 nM) in the hMAGL assay, only compound 10 represented an excellent starting point with reasonable selectivity towards MAGL over FAAH (30–50 fold; Figure S4, SI). No significant interactions of 10 were observed among two major cannabinoid receptors, CB1/CB2 (up to 30 μM concentration, Table 1 and Figure S5, SI) and two other serine hydrolases, ABHD6 and ABHD12 (up to 10 μM concentration, Table 1 and Figure S6, SI) that can contribute to the catabolism of 2-AG in the brain.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory properties of lead compound 10. (A) concentration-response curves for inhibition of 0.5 μM [3H]2-OG hydrolysis by rat brain MAGL, either without or with 60 min preincubation; (B) time-dependency of [3H]2-OG (0.5 μM) hydrolysis under three different concentrations (0.2, 0.6, and 1 nM) of 10 preincubated for the times shown; (C) the kinetics of inhibition by the compound (I, inhibitor 10) in the absence of pre-incubation and using a short incubation time (2 min); (D) the inhibition of 0.5 μM [3H]2-OG hydrolysis found by the compound in the absence of pre-incubation (white and orange bars) or in its presence after 60 min of pre-incubation followed by dilution to reduce the free concentration 20 fold (blue bar). For a reversible compound, the blue bar should match the corresponding white bar. Data are means ± SEM, n= 3–4 unless otherwise shown.

Table 1.

Binding affinity and physicochemical properties of compounds 8-11.

determined by [3H]2-OG hydrolysis assay using rat brain membrane with 0 min or 60 min pre-incubation (MAGL inhibitor JZL184 as positive control);

determined by human recombinant MAGL assay (MAGL inhibitor JZL195 as positive control);

determined by [3H]AEA hydrolysis assay using rat brain membrane with 0 min or 60 min pre-incubation (FAAH inhibitors URB597 and DOPP as positive controls);

determined by ABPP assay on rat brain membrane (MJN110 as positive control);

determined by agonist and antagonist CB1 and CB2 receptor assays (CP55940 as positive control in CB1/CB2 agonist assays; Rimonabant as positive control in CB1 antagonist assay and SR144528 as positive control in CB2 antagonist assay);

calculated by ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0;

measured by ‘shake-flask’ method quantified by LC-MS;

determined by PgP-Glo assay.

Test compounds (1 μM), ≤ 30% changes of luminescence signal (vs vehicle) are defined as ‘low PgP efflux liability’; verapamil was used as positive control. All data are acquired in average 3–5 runs. ND, not determined.

We also investigated the interaction of compound 10 with MAGL by molecular docking studies, the assumption being made that the initial interaction, not experimentally measurable due to the rapid formation of the covalent bond, is competitive in nature (Figure 1). The goal is to identify possible molecular interaction between MAGL inhibitors and binding domain based on the fact that excellent low nanomolar binding affinities (0.68 – 4.2 nM) were identified. Our approach was established upon the reported high-resolution structure of the ligand-protein complex with non-covalent inhibitor (PDB 3PE6).56 The noncovalent binding modes were first established via both Glide SP57 and XP58 methods (Glide, Schrödinger©). To account for the binding site flexibility, the binding interaction was further studied through Glide/Induced Fit Docking (IFD) runs.59 In general, IFD binding modes were found to show an optimized network of enzyme-ligand interactions as compared to the rigid docking results. The lead compound 10 showed a Glide XP docking score of −8.0 kcal/mol. The covalent docking results were obtained using Glide covalent docking60 and the estimated free-binding energy values were calculated using Prime MM/GBSA.61 Compound 10 exhibited a predicted covalent docking affinity of −7.40 kcal/mol, and ΔGbind of −44.03 kcal/mol. The resulting covalent binding complex was further refined via MarcoModel energy minimization to give the final binding pose (section 2, SI).61, 62

Lipophilicity of candidate compounds can be used as a predictive factor for blood-brain barrier permeability with a favorable range between 1.0 and 3.5.63–65 The cLogP values of compounds 8-11 were predicted to be 2.90, 2.90, 2.80 and 2.80, respectively (Table 1). Using liquid-liquid partition between n-octanol and water (‘shake flask method’),66 the LogP values for 8-11 were determined to be 1.45 ± 0.01, 1.42 ± 0.11, 1.23 ± 0.10 and 1.17 ± 0.14, respectively (n = 3). The candidate compounds 8-11 were also evaluated in PgP-ATPase assay to determine their interaction with recombinant human PgP membranes using verapamil as positive control. No significant response (<30% luminescent changes) was observed (Figure S7, SI). These results indicated high possibility for sufficient brain permeability and low efflux ratio of compounds 8-11.

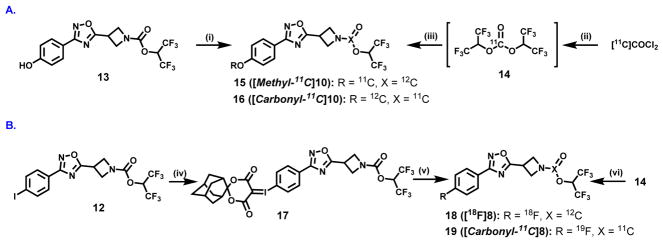

Radiochemistry

The importance of the labeling site at the 11C-carbonyl group was first shown by Wilson et. al.67 in the design of irreversible serine hydrolase radiotracers, including the FAAH tracer [11C]CURB67, 68 and our subsequent design of the MAGL tracer [11C]SAR127303.46 Therefore, for lead compound 10, we utilized two possible labeling strategies: (1) 11C-methylation of phenolic precursor 13; and (2) 11C-carbonylation via [11C]COCl2 fixation.69 The methyl ether was identified as the most convenient labeling site for compound 10 with carbon-11 (Scheme 2A, left). The precursor 13 for 11C-methylation was synthesized in 78% yield by demethylation reaction of 8 using BBr3. The radiosynthesis of 15 ([methyl-11C]10) was carried out by the reaction of the phenolic precursor 13 with [11C]CH3I in the presence of NaOH at 70 °C for 5 min. The reaction mixture was purified by a reverse phase semi-preparative HPLC, and reformulated for PET imaging studies. 15 was synthesized in an average of 13% decay-corrected radiochemical yield (RCY) based on [11C]CO2 at end-of-synthesis (30 min synthesis time) with >99% radiochemical purity (n = 3). The specific activity was greater than 3 Ci/μmol (110 GBq/μmol). Another site-specific radiosynthesis of 16 ([carbonyl-11C]10) was also performed based on our previously reported procedure46 using [11C]COCl2 (Scheme 2A, right). Reaction of [11C]COCl2 with HFIP generated 11C-carbonate 14 in the presence of 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine (PMP) in THF. Addition of the corresponding azetidine (generated from 5) at 30°C for 3 min afforded 16 in an average RCY of 11%, relative to starting [11C]CO2 at end-of-synthesis. The specific activity was high (> 56 GBq/μmol; 1.5 Ci/μmol) and radiochemical purity was greater than 99%. Both 15 and 16 showed no signs of radiolysis up to 90 min after formulation. To demonstrate the diversity of radiolabeling and evaluate brain permeability of fluorinated MAGL inhibitors, we also carried out 18F- and 11C-isotopologue labeling of 8. The corresponding spirocyclic iodonium ylide (SCIDY)70 precursor 17 for 18F-labeling was obtained from the oxidation of iodinated compound 12, followed by ligand exchange with SPIAd71 in 56% yield (Scheme 2B). The labeled compound 18 ([18F]8) was obtained in 28% RCY, using our SCIDY method70–75 and 19 ([carbonyl-11C]8) was generated in 13% RCY using analogous [11C]COCl2 protocol46 (Scheme 2B). Despite the fact that compound 19 exhibited high brain permeability (ca. 1.4 peak SUV, standardized uptake value; Figure S8, SI), further evaluation of this fluorinated scaffold, i.e., 18 and 19, was not pursued due to its limited in vitro selectivity between MAGL and FAAH. Based on its potency and selectivity, 11C-labeled 10 was selected to undergo subsequent evaluation by in vivo PET imaging and ex vivo biodistribution studies in rodents.

Scheme 2.

Site-specific 11C-labeling of (A) compound 10 and (B) compound 8. Conditions: (i) 11CH3I, NaOH, DMF, 70 °C, 5 min, 13% RCY; (ii) HFIP, PMP, THF, r.t., then (III) azetidine generated from 5 after Boc deprotection, THF, 30 °C, 3 min, 11% RCY; (iv) mCPBA, CHCl3, overnight, then SPIAd, 10% Na2CO3, EtOH, 5 h, 56% yield; (v) [18F]TEAB, DMF, 100 °C, 10 min, 28% RCY; (vi) azetidine generated from 3 after Boc deprotection, THF, 30 °C, 3 min, 13% RCY. See experimental section for details. RCY = decay-corrected radiochemical yield; HFIP = 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol; PMP = 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine; THF = Tetrahydrofuran; TEAF = Tetraethylammonium fluoride.

Preliminary PET imaging studies in rat brain

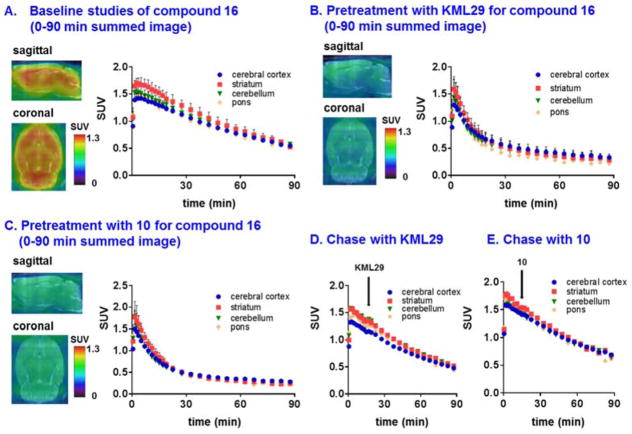

Dynamic PET acquisitions were carried out with 15 and 16 in Sprague-Dawley rats for 90 min. Representative PET images (coronal and sagittal, summed images 0–90 min) in whole brain and time-activity curves are shown in Figure 2 and Figure S9 (SI), respectively. 15 rapidly crossed the blood-brain barrier (>1 SUV) with heterogeneous distribution consistent with MAGL expression in rat brain (Figure S9, SI).46, 76 Pretreatment with non-radioactive 10 (self-blocking; 3 mg/kg i.v.) remarkably decreased whole brain uptake (ca. 40% reduction calculated by area under curve, AUC) and showed reasonable clearance of nonspecific binding (SUV2/40 min = ca. 3; Figure S9, SI). However, contrary to typical irreversibly binding covalent (‘suicide’) inhibitors that have been developed as radiotracers, which display characteristic plateaued time-activity curves,46, 67, 77 we observed slow washout (ratio of SUV5 min/SUV90 min = ca. 2) of bound radioactivity, which led us to initially question in vivo stability of 11C-methyl group of 10 before the implementation of blocking studies with other structurally-diverse MAGL inhibitors. We next investigated if site-specific labeling of 11C-carbonyl position of 10, i.e., compound 16, would display different in vivo kinetics and shed insight on the mechanism of binding. The distribution of 16 was heterogeneous with decreasing order from striatum, cerebellum, cerebral cortex to pons. The distribution pattern of 16 was consistent with the distribution of MAGL in rat brain (Figure 2A).46, 76 As shown in Figure 2B, pretreatment with a MAGL inhibitor KML2978 (3 mg/kg, 30 min i.v. before injection) resulted in average 50% reduction in whole brain uptake by AUC (Figure S10, SI). Pretreatment studies with non-radioactive 10 (3 mg/kg, 30 min i.v. before injection) also significantly decreased uptake in the selected brain regions (average 50% reduction in whole brain by AUC, Figure S11, SI), and abolished the difference of uptakes in different regions, including striatum, cerebellum, cerebral cortex and pons (Figure 2C). Blocking studies with a FAAH inhibitor URB59779 (3 mg/kg, 30 min i.v. before injection) showed no significant reduction (Figure S12, SI) in brain uptake, as predicted for this selective MAGL inhibitor 10. These results confirmed 16 has a high level of in vivo specific binding to MAGL.

Figure 2.

Representative PET images (0–90 min) and time-activity curves of 16 in rat brain: (A) baseline (n = 3), (B) blocking studies using KML29 (3 mg/kg pretreatment, 30 min i.v. before injection, n = 3), (C) self-blocking studies using non-radioactive 10 (3 mg/kg pretreatment, 30 min i.v. before injection, n = 3), (D) displacement studies using KML29 (3 mg/kg displacement, 15 min i.v. post injection, indicated by black arrow) and (E) chase studies using non-radioactive 10 (3 mg/kg displacement, 15 min i.v. post injection, indicated by black arrow).

To our surprise, a similar washout pattern to that seen for 15 (cf. Figure S9) was also observed with 16, which argues against instability of the 11C-methyl group as being responsible for the kinetics. In consequence, we investigated the in vivo reversibility of 16 binding to MAGL. We next performed displacement (“chase”) studies using KML29 or non-radioactive 10 (3 mg/kg i.v. for both cases) at 15 min post-injection of 16 (Figure 2D and 2E). Nearly identical time-activity curves were found between control and chase studies, which supports the expected irreversible binding mechanism of 16 to MAGL. These results further support our hypothesis that the unexpected clearance of 16 in rat brain is thus presumably due to in vivo dissociation of the azetidine carbonyl and the target serine residue of MAGL. PET imaging studies utilizing 16 not only unveiled unexpected kinetics that are likely caused by the azetidinyl carbamate moiety, but also may provide a semi-quantitative method to measure in vivo dissociation rates (turnover of the covalent adduct) between the azetidinyl scaffold and MAGL, i.e., in this case, the dissociation rate can be expressed by the ratio between SUV5 min and SUV90 min (the value is ca. 2). We also carried out radiometabolite analysis in mouse brain and found that more than 90% radioactivity was irreversibly bound to the brain at 5 and 30 min post injection of 16 (Table S1, SI). These results together with blocking studies, in a large extent, diminished the possibility that the unexpected washout was caused by brain penetrant radiometabolites that are not irreversibly binding, or not binding at all to MAGL.

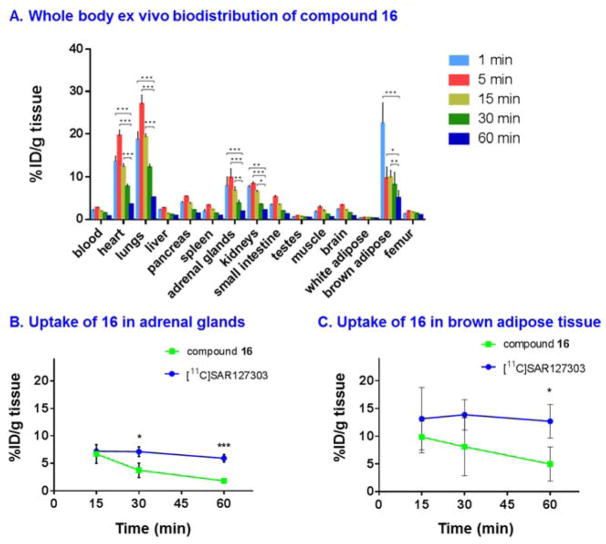

Whole body ex vivo biodistribution studies

The uptake, distribution and clearance of 16 were studied in mice at five time points (1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min) post-injection of the radiotracer (Figure 3A and Table S2 & S3, SI). High uptake (>3% ID/g) was observed in several organs including heart, lungs, pancreas, adrenal glands, kidneys, small intestine and brown adipose tissue (BAT) at 1 and 5 min post injection. After the initial uptake, the radioactivity in all tissues of interest decreased rapidly, while the signals in the heart, lungs, adrenal glands, kidneys and brown adipose tissue remained at a high level (>3% ID/g). The radioactivity was efficiently cleared from blood (1/60 min ratio of 3.2) and high radioactivity in the kidneys, liver and small intestine indicated urinary and hepatobiliary elimination. The distribution of 16 in the peripheral organs was consistent with that of prior report of high MAGL expression in the heart, lungs, adrenal glands and BAT.46 We also carried out blocking studies using KML29 (3 mg/kg) and high specific binding was observed in peripheral MAGL-rich organs, including but not limited to heart, lungs, BAT, kidneys, brain and adrenal glands (Figure S13).

Figure 3.

(A) Ex vivo biodistribution in mice at five different time points (1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min) post injection of compound 16. Comparison of bound activity washout between [11C]SAR127303 and compound 16 in two MAGL-rich tissues: (B) adrenal glands and (c) brown adipose tissue. All data are mean ± SD, n = 3–5. Statistical significance was determined with Two-way ANOVA or Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p≤ 0.001

In order to determine whether the dissociation between 16 and MAGL is restricted to the brain, we examined washout rate of bound activities in two peripheral MAGL-rich organs, namely adrenal glands and BAT, and compared it with that of a known irreversible MAGL tracer, [11C]SAR127303.45, 46 The uptake of the two tracers in adrenal and BAT was plotted at 15, 30 and 60 min post injection (Figure 3B and 3C), the results of which indicated the target dissociation of 16 was systematic and time-dependent.

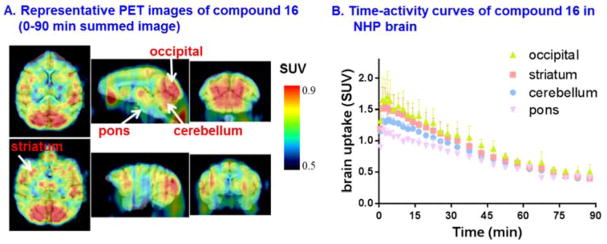

Preliminary PET imaging studies in nonhuman primate

As binding affinities of compounds targeting MAGL are known to differ amongst species,28 our efforts focused on preliminary PET imaging of 16 in higher species, i.e., NHPs to investigate brain permeability, regional distribution and particularly washout kinetics. Representative PET images in NHP brain are shown in Figure 4A. 16 is brain penetrant with peak brain uptake greater than 1.5 SUV. The distribution was heterogeneous with the highest uptake observed in the decreasing order of occipital cortex (1.7 SUV), striatum (1.5 SUV), cerebellum (1.3 SUV), and the lowest uptake in pons (1.1 SUV), which is consistent with MAGL distribution.76 The plasma metabolism was rapid with unchanged 16 fraction, 33% at 1 min, 7% at 15 min and 1% at 15 min, respectively, with only one other more polar metabolite observed. In terms of washout kinetics, the radioactivity peaked 2 min post injection, then slowly cleared out over 90 min with ratio of ca. 3 between SUV5 min and SUV90 min, which confirmed in vivo dissociation of the radiolabeled azetidine scaffold and MAGL in the living brain (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Representative PET images (0–90 min) and (B) time-activity curves of 16 in NHP brain.

CONCLUSION

An array of azetidinyl carbamates targeting MAGL were efficiently synthesized, among which compound 10 (MAGL-0519) was identified as the most promising inhibitor. Potency, selectivity and irreversible binding mechanism were determined in vitro by MAGL hydrolysis assays, ABPP, CB1/CB2 agonist and antagonist assays, and dilution experiments. Physiochemical properties including lipophilicity (LogP) and PgP efflux liability were also measured and these studies demonstrated that 10 is an excellent new leading scaffold for exploration as a MAGL inhibitor. Diverse radiolabeling strategies, including site specific 11C-labeling and SCIDY radiofluorination method were employed to provide 11C- or 18F-isotopologues of MAGL inhibitors in excellent radiochemical yields and high radiochemical purity. The pharmacokinetic profile including brain uptake, clearance, binding specificity and irreversibility was evaluated by PET and ex vivo whole body distribution in rodents, and further supported by proof-of-concept NHP imaging studies. While 16 showed moderate-to-high in vitro and in vivo specific binding and irreversible binding mechanism, further optimization to overcome unexpected washout is needed. As a result, this work not only offers a new roadmap for medicinal chemistry efforts towards new azetidine carboxylate-based MAGL PET tracers with improved metabolic stability, but also enables in vivo PET imaging studies in drug discovery towards MAGL inhibitors.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Consideration

All the chemicals employed in the syntheses were purchased from commercial vendors and used without further purification. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was conducted with 0.25 mm silica gel plates (60F254) and visualized by exposure to UV light (254 nm) or stained with potassium permanganate. Flash column chromatography was performed using silica gel (particle size 0.040–0.063 mm). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained either on a Bruker spectrometer 300 MHz or on a Bruker spectrometer 400 MHz. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm and coupling constants are reported in Hertz. The multiplicities are abbreviated as follows: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, quint = quintet, sext = sextet, sept = setpet, m = multiplet, br = broad signal, dd = doublet of doublets. For mass spectrometer measurement, the ionization method is ESI using Agilent 6430 Triple Quad LC/MS. Lipophilicity was calculated by ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0 (CambridgeSoft Corporation, PerkinElmer, USA). All tested MAGL inhibitors showed purity more than 95% as determined by reverse-phase HPLC (Cosmosil C18 column (4.6 mm ID × 250 mm); mobile phase MeOH/H2O (v/v, 75/25); flowrate 1.0 mL/min and detection wavelength 254 nm). The lead compounds 8-11 didn’t show any promiscuous moieties in the Pan Assay Interference Compounds Assay (PAINS) using two independent in silico filters.80 The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Massachusetts General Hospital or the Animal Ethics Committee at the National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology, National Institute of Radiological Sciences. DdY mice (male; 7 weeks, 34–36 g), Sprague-Dawley rats (male; 7 weeks; 210–230 g) were kept on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle and were allowed food and water ad libitum.

Chemistry

General procedure for synthesis of compound 3-6

Et3N (4 mmol) was added to a solution of 1 (2 mmol) and the appropriate Boc-protected amino acid 2 (2.4 mmol) in DMF (10 mL). HBTU (2.4 mmol) was then added to the resulting mixture at r.t. and stirred at 100 °C overnight. Upon the completion of reaction monitored by TLC, the solution was partitioned between ethyl acetate and water. The organic layer was washed several times with saturated aqueous LiBr solution. The aqueous solution was then extracted with ethyl acetate and the combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (3/1 hexanes/EtOAc) to give the desired product.

Preparation of tert-butyl 3-(3-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (3)

Compound 3 was prepared in 94% yield as a white solid. Melting point: 92–94 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.16–8.01 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.12 (m, 2H), 4.45–4.26 (m, 4H), 4.10–3.98 (m, 1H), 1.47 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.1, 167.8, 164.6 (d, J = 251.9 Hz), 155.9, 129.6 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 122.7 (d, J = 3.3 Hz), 116.1 (d, J = 22.1 Hz), 80.2, 53.1, 28.3, 25.7; 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3) δ −108.1. HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C16H19FN3O3+, 320.1410, found 320.1407.

Preparation of tert-butyl 3-(3-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (4)

Compound 4 was prepared in 98% yield as a white solid. Melting point: 75–77 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.89 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.83–7.75 (m, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 13.8, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.17 (m, 1H), 4.45–4.27 (m, 4H), 4.12–3.99 (m, 1H), 1.47 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.3, 167.7 (d, J = 3.0 Hz), 162.9 (d, J = 246.9 Hz), 155.9, 130.6 (d, J = 8.1 Hz), 128.5 (d, J = 8.5 Hz), 123.2 (d, J = 3.2 Hz), 118.3 (d, J = 21.2 Hz), 114.5 (d, J = 23.7 Hz), 80.2, 53.1, 28.3, 25.7; 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3) δ −111.8. Characterization confirmed by comparison with published characterization data.53

Preparation of tert-butyl 3-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (5)

Compound 5 was prepared in 92% yield as a white solid. Melting point: 67–69 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.01 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.33 (dt, J = 14.7, 8.7 Hz, 4H), 4.07–3.97 (m, 1H), 3.86 (s, 1H), 1.46 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.6, 168.2, 162.0, 155.9, 129.0, 118.9, 114.3, 80.1, 55.4, 55.3, 28.3, 25.7.

Preparation of tert-butyl 3-(3-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (6)

Compound 6 was prepared in 99% yield as a white solid. Melting point: 62–64 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.67 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.57 (m, 1H), 7.38 (td, J = 8.2, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.40–4.29 (m, 4H), 4.08–4.00 (m, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 1.46 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.9, 168.5, 159.9, 155.8, 123.0, 127.6, 119.9, 117.8, 112.0, 80.2, 55.4, 55.3, 28.3, 25.7.

Preparation of tert-butyl 3-(3-(4-iodophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (7)

Compound 7 was prepared in a manner similar to that described for 3-6 in 94% yield as a white solid. Melting point: 109–110 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.90–7.76 (m, 4H), 4.47–4.26 (m, 4H), 4.10–3.98 (m, 1H), 1.47 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.2, 168.0, 155.9, 138.1, 128.9, 126.0, 98.1, 80.2, 53.1, 28.3, 25.7. HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C16H19IN3O3+, 428.0471, found 428.0470.

General procedure for synthesis of MAGL inhibitor 8-11

Trifluoroacetic acid (40 mmol) was added to a solution of oxadiazoles 3-6 (2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (8 mL). The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature overnight. Upon the completion of reactions, the mixture was neutralized with saturated aqueous Na2CO3, and extracted with ethyl acetate (15 mL x 3). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, and dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue could be used in the next steps without extra purification. A solution of 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate (4 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) was added dropwise to a solution of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (10 mmol), pyridine (10 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (0.24 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) at 0 °C under argon. The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature overnight, followed by the addition of amine (4 mmol) obtained in previous step and triethylamine (12 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 8 hours, then evaporated to dryness and re-dissolved in ethyl acetate (100 mL). The organic phase was washed with H2O (100 mL x 4), 1 M aqueous potassium carbonate solution (100 mL) and brine (100 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel, elution being carried out with a 1 : 9 mixture of ethyl acetate and hexanes.

Preparation of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (8)

Compound 8 was prepared in 85% yield for two steps as a white solid. Melting point: 45–46 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.13 (m, 2H), 5.68 (sept, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.69–4.43 (m, 4H), 4.21 (tt, J = 9.0, 6.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.0, 167.9, 164.7 (d, J = 252.2 Hz), 151.5, 129.6 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 122.4 (d, J = 3.3 Hz), 120.6 (q, J = 280.9 Hz), 120.5 (q, J = 280.9 Hz), 116.1 (d, J = 22.1 Hz), 67.8 (hept, J = 34.7 Hz), 54.0, 53.4, 26.3; 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3) δ −73.6 (d), −107.8. HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C15H11F7N3O3+, 414.0689, found 414.0690. Retention time = 16.79 min, HPLC k′ value = 3.6.

Preparation of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (9)

Compound 9 was prepared in 63% yield for two steps as a white solid. Melting point: 38–39 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.89 (ddd, J = 7.7, 1.4, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (ddd, J = 9.4, 2.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (td, J = 8.0, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (ddd, J = 8.4, 2.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (hept, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.69–4.45 (m, 4H), 4.22 (tt, J = 9.0, 6.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.2, 167.8 (d, J = 3.1 Hz), 162.9 (d, J = 247.1 Hz), 151.5, 130.7 (d, J = 8.1 Hz), 128.2 (d, J = 8.5 Hz), 123.2 (d, J = 3.2 Hz), 120.6 (q, J = 280.7 Hz), 120.5 (q, J = 280.7 Hz), 118.5 (d, J = 21.2 Hz), 114.5 (d, J = 23.8 Hz), 67.7 (hept, J = 34.6 Hz), 54.0, 53.4, 26.3; 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3) δ −73.6 (d), −111.6. HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C15H11F7N3O3+, 414.0689, found 414.0691. Retention time = 18.38 min, HPLC k′ value = 4.0.

Preparation of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (10)

Compound 10 was prepared in 81% yield for two steps as a white solid. Melting point: 84–85 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.03 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 5.68 (sept, J = 6.2 Hz,, 1H), 4.68–4.39 (m, 4H), 4.27–4.10 (m, 1H), 3.88 (s, 3H).; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.6, 168.4, 162.2, 151.5, 129.1, 120.6 (q, J = 284.8 Hz), 120.5 (q, J = 284.8 Hz), 118.7, 114.4, 67.8 (hept, J = 34.8 Hz), 55.4, 54.1, 53.5, 26.3. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −73.6 (d). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C16H14F6N3O4+, 426.0889, found 426.0887. Retention time = 16.09 min, HPLC k′ value = 3.4.

Preparation of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (11)

Compound 11 was prepared in 65% yield for two steps as a white solid. Melting point: 78–80 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.69 (dt, J = 7.7, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.63–7.59 (m, 1H), 7.41 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (ddd, J = 8.3, 2.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (sept, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.69–4.48 (m, 4H), 4.29–4.14 (m, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.9, 168.7, 160.0, 151.5, 130.1, 127.4, 120.6 (q, J = 284.7 Hz), 120.5 (q, J = 284.7 Hz), 119.9, 118.0, 112.0, 67.8 (hept, 34.8 Hz), 55.5, 54.1, 53.4, 26.3. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −73.6 (d). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C16H14F6N3O4+, 426.0889, found 426.0890. Retention time = 16.72 min, HPLC k′ value = 3.6.

Preparation of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(4-iodophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (12)

Compound 12 was prepared in a manner similar to that described for 8-11 in 73% yield for two steps as a white solid. Melting point: 86–87 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.95 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.56 (sept, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 4.61–4.20 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO) δ 180.1, 167.6, 151.5, 138.7, 129.2, 126.0, 121.2 (q, J = 282.7 Hz), 121.1 (q, J = 282.7 Hz), 99.5, 67.3 (hept, J = 33.4 Hz), 54.3, 53.7, 26.3; 19F NMR (282 MHz, DMSO) δ −72.8 (d). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C15H11F6IN3O3+, 521.9749, found 521.9747.

Preparation of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (13)

Hexafluorocarbamate compound 10 (0.213 g, 0.5 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (2.5 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. To this solution was added BBr3 (3 mL, 1.0 M in DCM, 3 mmol) dropwise at 0 °C and gradually warmed up to room temperature. The reaction was kept at room temperature until the completion of the reaction as determined by TLC. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (10 mL) and was extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine (3 × 10 mL) and subsequently dried with Na2SO4. The solution was concentrated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue purified via silica gel chromatography. Compound 13 was prepared in 78% yield as a white solid. Melting point: 163–164 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.16 (br s, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.69 (sept, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 4.62–4.42 (m, 2H), 4.40–4.19 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 179.3, 168.0, 160.9, 151.6, 129.3, 120.3 (q, JC–F = 282.6 Hz), 120.2 (q, JC–F = 282.6 Hz), 117.2, 116.4, 67.4 (hept, JC–F = 34.8 Hz), 54.4, 53.8, 26.3. 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO) δ −72.8 (d). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated forC15H12F6N3O4+, 412.0732, found 412.0735.

Preparation of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(4-(((1r,3r,5r,7r)-4′,6′-dioxospiro[adamantane-2,2′-[1,3]dioxan]-5′-ylidene)-l3-iodanyl)phenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (17)

The SCIDY precursor 7 could be obtained with 56% yield in two steps by following our previous reported methods.70–73, 75 The aryl iodide 12 could be oxidized in chloroform.70 Without further purification, the resulted intermediate could couple the spirocyclic auxiliaries (SPIAd)71 directly to afford the desired ylide precursor 17. In specific, oxidant mCPBA (1.3 mmol, 77% max. content) was added to a solution of aryl iodide 12 (1 mmol) in chloroform (10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The solvent was then removed by rotary evaporation. The dried residue was suspended in ethanol (10 mL) and (1r,3r,5r,7r)-spiro[adamantane-2,2′-[1,3]dioxane]-4′,6′-dione (SPIAd, 1 mmol) was added followed by 10% Na2CO3(aq) (w/v, 10 mL, 0.33 M solution). The pH of the reaction mixture was tested and adjusted with Na2CO3 until the reaction pH > 10. The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 h until full conversion of to the iodoinium ylide was determined by TLC. The reaction mixture was then diluted with water, and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layers were combined and washed with water and brine. The organic layer was dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel, elution being carried out with 1 : 1 mixture of ethyl acetate and hexanes. The product was obtained as light yellow solid. Melting point: 48–50 °C. Yield: 56% over two steps. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.08 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.56 (hept, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 4.62–4.21 (m, 5H), 2.34 (s, 2H), 1.94 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 4H), 1.79 (s, 2H), 1.66 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO) δ 180.3, 167.2, 163.0, 151.5, 133.6, 129.7, 128.5, 121.2 (q, J = 280.5 Hz), 121.1 (q, J = 280.5 Hz), 119.6, 105.7, 67.3 (hept, J = 33.4 Hz), 58.0, 54.3, 53.7, 36.9, 35.3, 33.6, 26.4, 26.3; 19F NMR (282 MHz, DMSO) δ −72.8 (d). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C28H25F6IN3O7+, 756.0641, found 756.0643.

Pharmacology

Hydrolysis of [3H]2-OG and [3H]AEA

The assays were undertaken using cytosolic and membrane preparations, respectively, from rat brain. The hydrolysis was measured using the method of Boldrup et al.81 whereby test compounds, brain samples and assay buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) are preincubated for 0–60 min prior to addition of substrate ([3H]2-OG for MAGL, [3H]AEA for FAAH, both obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and diluted with non-radioactive 2-OG and AEA, as appropriate (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) to give the final assay concentration (0.5 μM unless otherwise stated, in assay buffer containing 0.125% w/v assay concentration of fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin) in an assay volume of 200 μL. Reactions were stopped by addition of 400 μL of a solution containing 40 mL of active charcoal and 160 mL of 0.5 M HCl. Phases were separated by centrifugation and the aqueous phase, containing the reaction products, were taken and measured for tritium content using liquid scintillation spectroscopy with quench correction. pIC50 and hence IC50 values were determined on the data expressed as % of control using the log(inhibitor) vs. response - variable slope algorithm of GraphPad Prism. Using this assay, we have previously reported that [3H]2-OG hydrolysis is inhibited by the selective MAGL inhibitor JZL184 with IC50 values of 350, 12 and 5.8 nM following preincubation for 0, 30 and 60 min, respectively82 whilst the hydrolysis of [3H]AEA is completely blocked by 100 nM of the selective FAAH inhibitor URB597.68 MAGL inhibitor JZL184 was used as positive control in [3H]2-OG assay, which gave pIC50 values of 6.46±0.04 (without preincubation) and 8.24±0.02 (60 min preincubation), respectively. FAAH inhibitor DOPP83 was used as positive control in [3H]AEA assay, which generated pIC50 value of 9.09±0.04 (60 min preincubation).All data are acquired in average 3–4 runs.

In vitro human recombinant MAGL inhibition enzyme assays

IC50 values of testing compounds 8 and 10 were determined by literature procedure84 and manufacturer’s instructions from commercially available MAGL inhibitor screening kits (Cayman Chemical, Inc.). JZL195 (4.4 μM) was used as positive control as per manufacturer’s instruction, which completely blocked human recombinant MAGL hydrolysis. Dose-response simulation function in GraphPad Prism was used for data processing. All data are acquired in average 3–5 runs. The results are shown in Table 1 and Figure S3.

Binding affinities to CB1 and CB2 receptors

CB1 and CB2 binding profiles of 8-11 were determined according to published literatures85, 86 and supported by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program. The detailed procedures “assay protocol book” are listed on the website (https://pdspdb.unc.edu/pdspWeb/). In specific, compound CP55940 was used as positive control in CB1/CB2 agonist assays; Rimonabant as used as positive control in CB1 antagonist assay and SR144528 was used as positive control in CB2 antagonist assay. All data are acquired in average 3–5 runs. The results are shown in Table 1 and the corresponding dose response curves are shown in Figure S5 in the supporting information.

Activity based protein profiling (ABPP)

General procedure:55 Mouse brain membrane proteomes (1 mg/mL) were preincubated with either DMSO or inhibitors (1 μM and 10 μM) at 37 °C. After 30 min, FP-rhodamine (1 μM final concentration) was added and the mixture was incubated for another 1 to 180 min at room temperature. Reactions were quenched with 4 X SDS loading buffer and run on SDS-PAGE. Samples were visualized by in-gel fluorescence scanning using a ChemiDoc MP system. For time course experiment, proteomes are treated with 1 μM and 10μM of compounds 8-11 for 30 min @ 37 °C followed by labeling with FP-Rh (1 μM final concentration) for varying time @ room temperature. DMSO as negative control and MJN110 [2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 4-(bis(4-chlorophenyl)methyl) piperazine-1-carboxylate],87 a validated irreversible MAGL inhibitor, as positive control. The relative intensity was compared to the DMSO treated proteomes, which were set to 100%. All data are acquired in average 3 runs. The percentage of enzyme activity remaining was determined by measuring the integrated optical intensity of the fluorescent protein bands using image lab 5.2.1.

Molecular Modeling

Covalent docking was performed with iterative energy minimization in YASARA,88 using as input the output complex structure generated from flexible, non-covalent docking in the Schrödinger suite of programs. Starting with the best pose from flexible, non-covalent docking, a covalent bond was formed in silico in YASARA. Energy minimization, using the YAMBER389 force field, was performed on the covalently bound complex. See section 2, SI for details.

Radiochemistry

Radiolabeling of 15

[11C]CH3I was synthesized from cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2, which was produced by 14N(p, α)11C nuclear reaction. Briefly, [11C]CO2 was bubbled into a solution of LiAlH4 (0.4 M in THF, 300 μL). After evaporation, the remaining reaction mixture was treated with hydroiodic acid (57% aqueous solution, 300 μL). The resulting [11C]CH3I was transferred under helium gas with heating into a pre-cooled (−15 to −20 °C) reaction vessel containing precursor 13 (1.0 mg), NaOH (4.9 μL, 0.5 M) and anhydrous DMF (300 μL). After the radioactivity reached a plateau during transfer, the reaction vessel was warmed to 70 °C and maintained for 5 min. CH3CN/H2O + 0.1% Et3N (v/v, 75/25, 0.5 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, which was then injected to a semi-preparative HPLC system. HPLC purification was completed on a Capcell Pak UG80 C18 column (10 mm ID × 250 mm) using a mobile phase of CH3CN/H2O + 0.1% Et3N (v/v,75/25) at a flowrate of 5.0 mL/min. The retention time for 15 was 8.0 min. The radioactive fraction corresponding to the desired product was collected in a sterile flask, evaporated to dryness in vacuo, and reformulated in a saline solution (3 mL) containing 100 μL of 25% ascorbic acid in sterile water and 100 μL of 20% Tween® 80 in ethanol. (Note: We added ascorbic acid to prevent potential radiolysis and Tween® 80 to improve aqueous solubility.) The synthesis time was ca. 30 min from end-of-bombardment. Radiochemical and chemical purity were measured by analytical HPLC (Capcell Pak UG80 C18, 4.6 mm ID × 250 mm, UV at 254 nm; CH3CN/H2O + 0.1% Et3N (v/v, 80/20) at a flowrate of 1.0 mL/min). The identity of 15 was confirmed by the co-injection with unlabeled 10. Radiochemical yield was 13.1 ± 0.2% (n = 3) decay-corrected based on [11C]CO2 with >99% radiochemical purity and the molar activity was 117.80–254.24 GBq/μmol (3.18–6.73 Ci/μmol).

Radiolabeling of 16

[11C]CO2 was produced by 14N(p, α)11C nuclear reactions in cyclotron, and transferred into a pre-heated methanizer packed with nickel catalyst at 400 °C to produce 11CH4, which was subsequently reacted with chlorine gas at 560 °C to generate [11C]CCl4. [11C]COCl2 was produced via the reactions between [11C]CCl4 and iodine oxide and sulfuric acid,46 and trapped in a solution of hexafluoroisopropanol (5.00 mg) and 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine (PMP; 5.2 μL) in THF (200 μL) at 0 °C. A solution of azetidine 5 (1.00 mg) and PMP (1.0 μL) in THF (200 μL) was added into the mixture and heated at 30 °C for 3 min before cooling to ambient temperature. The reaction mixtures were concentrated to remove THF, then diluted with HPLC mobile phase (500 μL), followed by the injection on HPLC column. HPLC purification was performed on a Capcell Pak C18 column (10 × 250 mm, 5 μm) using a mobile phase of CH3CN/H2O + 0.1% Et3N (75/25, v/v) at a flowrate of 5.0 mL/min. The retention time of 16 was 8.0 min. The product solution was concentrated by evaporation, and reformulated in a saline solution (3 mL) containing 100 μL of 25% ascorbic acid in sterile water and 100 μL of 20% Tweenα 80 in ethanol. (Note: We added ascorbic acid to prevent potential radiolysis and Tweenα 80 to improve aqueous solubility.) The radiochemical and chemical purity were measured by an analytical HPLC (Capcell Pak C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5μm). The identity of 16 was confirmed by the co-injection with unlabeled 10. The radiochemical yield was 6% on average (n = 3) decay-corrected based on [11C]CO2 with > 99% radiochemical purity and the molar activity was 60.55–69.74 GBq/μmol (1.64–1.89 Ci/μmol).

Radiofluorination for 18F-labeled 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (18)

[18F]fluoride was trapped on an ion exchange cartridge (Waters QMA, Part No. 186004540) from 18O-enriched water and subsequently released with a solution of tetraethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB, 3 mg) in 1 mL of CH3CN/H2O (v/v 7:3) into a 5 mL V-shaped vial sealed with a teflon septum. The solution was evaporated at 110 °C while nitrogen gas was passed through a P2O5-Drierite column into the vented vial. The evaporation was repeated three times with addition of dry acetonitrile (1 mL) each time. After that, the dried [18F]fluoride was re-dissolved in 0.3 mL of dry CH3CN. To an oven-dried vial containing precursor 13 (4.5 mg) and a magnetic stirrer bar was added anhydrous CH3CN (0.3 mL), followed by addition of a solution of [18F]TEAF (tetraethylammonium [18F]fluoride) in CH3CN (0.1 mL). The vial was sealed and heated at 100 °C for 10 min. After the reaction completed, mixture aliquot was taken for analysis by radioTLC (eluent: ethyl acetate) for radiochemical conversion (RCC). TLC plates (Silica gel 60, 10 × 2 cm) were spotted with an aliquot (2–5 μL) of crude reaction mixture approximately 1.5 cm from the bottom of the plate (baseline). TLC plates were developed in a chamber containing mixture of ethyl acetate until within 2 cm from the top of the plate (front). Analysis was performed using a Bioscan AR-2000 radioTLC imaging scanner. Radiochemical identity and purity were determined by radioHPLC. A Phenomenex Luna C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 10 μm HPLC column was used for the analytical analysis with a Waters 1515 Isocratic HPLC Pump equipped with a Waters 2487 Dual λ Absorbance Detector, a Bioscan Flow-Count equipped with a NaI crystal, and Breeze software. The flow rate for analytical HPLC analysis was 1 mL/min. Product identity was determined via co-injection with nonradioactive standard. Whereas, the semi-preparative purifications were performed on a Phenomenex Luna C18, 250 × 10.0 mm, 10 μm HPLC column with 0.1 M NH4·HCO2 (aq) as mobile phase and the flow rate was 5 mL/min. The radiochemical and chemical purity were measured by an analytical HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5μm). The identity of 18 was confirmed by the co-injection with unlabeled 8. The radiochemical yield was 28 ± 2% (n = 3) decay-corrected based on starting [18F]fluoride with > 99% radiochemical purity and the molar activity was greater than 1 Ci/μmol.

Radiosynthesis of 11C-carbonyl labeled 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl 3-(3-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)azetidine-1-carboxylate (19)

[11C]CO2 was produced by 14N(p, α)11C nuclear reactions in cyclotron, and transferred into a pre-heated methanizer packed with nickel catalyst at 400 °C to produce [11C]CH4, which was subsequently reacted with chlorine gas at 560 °C to generate [11C]CCl4. [11C]COCl2 was produced via the reactions between [11C]CCl4 and iodine oxide and sulfuric acid, and trapped in a solution of hexafluoroisopropanol (5.00 mg) and 1,2,2,6,6-penta methylpiperidine (PMP; 5.2 μL) in THF (200 μL) at 0 °C. A solution of azetidine 3 (1.00 mg) and PMP (1.0 μL) in THF (200 μL) was added into the mixture and heated at 30 °C for 3 min before cooling to ambient temperature. The reaction mixtures were concentrated to remove THF, then diluted with HPLC mobile phase (500 μL), followed by the injection on HPLC column. HPLC purification was performed on a Capcell Pak C18 column (10 × 250 mm, 5 μm) using a mobile phase of CH3CN/H2O + 0.1% Et3N (75/25, v/v) at a flowrate of 5.0 mL/min. The retention time of 19 was 8.5 min. The product solution was concentrated by evaporation, and reformulated in a saline solution (3 mL) containing 100 μL of 25% ascorbic acid in sterile water and 100 μL of 20% Tween® 80 in ethanol. The radiochemical and chemical purity were measured by an analytical HPLC (Capcell Pak C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5μm). The identity of 19 was confirmed by the co-injection with unlabeled 8. The radiochemical yield was 13.1 ± 2.2% (n = 3) decay-corrected based on [11C]CO2 with > 99% radiochemical purity and the molar activity was greater than 1 Ci/μmol.

Ex vivo biodistribution of 16 in mice

A solution of 16 (50 μCi/150–200 μL) was injected into Ddy mice via tail vein. These mice (each time point n = 3) were sacrificed at 1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min post tracer injection. Major organs, including whole brain, heart, liver, lung, spleen, kidneys, small intestine (including contents), muscle, testes, and blood samples were quickly harvested and weighted. The radioactivity present in these tissues was measured using 1480 Wizard gamma counter (PerkinElmer, USA), and all radioactivity measurements were automatically decay corrected based on half-life of carbon-11. The results are expressed as the percentage of injected dose per gram of wet tissue (% ID/g) or standardized uptake value (SUV).

Small-animal PET imaging studies

PET scans were acquired by an Inveon PET scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA). Sprague-Dawley rats were kept under anesthesia with 1–2% (v/v) isoflurane during the scan. The radiotracer (ca. 1 mCi/150–200 μL) was injected via a preinstalled catheter via tail vein. A dynamic scan in 3D list mode was acquired for 90 min. For pretreatment studies, 10 (3 mg/kg), KML29 (3 mg/kg) or URB597 (3 mg/kg) dissolved in 300 μL saline containing 5% ethanol, 5% DMSO and 5% Tween® 80 was injected at 30 min via the tail vein catheter before the injection of 16. For displacement (“chase”) studies, KML29 (3 mg/kg) was injected at 15 min via the tail vein catheter after the injection of 16. As we previously reported,46, 90, 91 the PET dynamic images were reconstructed using ASIPro VW software (Analysis Tools and System Setup/Diagnostics Tool, Siemens Medical Solutions). Volumes of interest, including the whole brain, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, striatum, thalamus and pons were placed referencing the MRI template software. The radioactivity was decay-corrected and expressed as the standardized uptake value. SUV = (radioactivity per mL tissue/injected radioactivity) x body weight.

The extent of irreversible binding for brain homogenate

Following the intravenous injection of 16, ddY mice (n = 3) were sacrificed at 5 and 30 min post injection, respectively. The mouse brain was quickly removed and homogenized in an ice-cooled CH3CN/H2O (v/v 1/1, 1 mL) solution. The homogenate was centrifuged at 150,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected. The supernatants were carefully decanted and the pellets were resuspended in the same volume of extraction solvent. The procedure was repeated in triplicate. The combined supernatants from each mouse were weighed, and aliquots counted for radioactivity. Each pellet was also counted for radioactivity. The percentage of bound activity in the brain was calculated based on literature procedures.67, 68

PET study in nonhuman primates

A male rhesus monkey (weight range 5.26–5.72 kg) underwent PET scan (Hamamatsu SHR-7700 animal PET scanner) while awake. A solution of 16 (3.70–3.71 mCi) in saline was injected into the monkey via a flexible percutaneous venous catheter, followed by a 90 min dynamic PET scan with the head centered in the field of view. The co-registration of PET image to individual MR image was based on a literature method.92 The same parameter was used for the transformation of co-registered PET image into the brain template MR and for the individual MR image. Each ROI was delineated on the brain template MR image. Time-activity curves were extracted from the corresponding ROIs and brain uptake of radioactivity was decay-corrected to the time of injection and expressed as SUV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (NIMH PDSP; directed by Bryan L. Roth at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Jamie Driscoll at NIMH) for in vitro screening. R.C. is supported by China Scholarship Council (201506250036). M.J.O. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation under grants # CHE-1305655 and MCB-1517290. N.V. acknowledges the National Institute on Ageing of the NIH for funding (R01AG054473). C.J.F. acknowledges the Swedish Science Research Council (nr 12158, medicine) for funding. B.F.C. acknowledges support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) under grants DA033760. S.H.L is a recipient of NIH career development award (DA038000) and Early Career Award in Chemistry of Drug Abuse and Addiction (ECHEM, DA043507) from NIDA.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PET

positron emission tomography

- eCB

endocannabinoid system

- AEA

anandamide

- 2-AG

2-arachidonoylglycerol

- [3H]2-OG

[3H]2-oleoylglycerol

- MAGL

monoacylglycerol lipase

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- ABPP

activity based protein profiling

- SUV

standardized uptake value

- TAC

time-activity curve

- %ID/g

percentage of injected dose per gram of wet tissue

- PgP

P-glycoprotein

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- SCIDY

spirocyclic iodonium ylide

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Characterization of all new compounds and NMR spectra; assay methods; computational docking studies; PET imaging procedures; supplemental figures and tables; molecular formula strings. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and function expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. The endogenous cannabinoid system and its role in nociceptive behavior. J Neurobio. 2004;61:149–160. doi: 10.1002/neu.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pertwee R. The pharmacology of cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: an overview. Int J Obes. 2006;30:S13–S18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn K, McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Enzymatic pathways that regulate endocannabinoid signaling in the nervous system. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1687–1707. doi: 10.1021/cr0782067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaltonen N, Ribas CR, Lehtonen M, Savinainen JR, Laitinen JT. Brain regional cannabinoid CB1 receptor signalling and alternative enzymatic pathways for 2-arachidonoylglycerol generation in brain sections of diacylglycerol lipase deficient mice. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;51:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marzo VD, Melck D, Bisogno T, Petrocellis LD. Endocannabinoids: endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligands with neuromodulatory action. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:521–528. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:389–462. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.2. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.58.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bisogno T, Marzo VD. Short- and long-term plasticity of the endocannabinoid system in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56:428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hohmann AG, Suplita RL. Endocannabinoid mechanisms of pain modulation. The AAPS Journal. 2006;8:E693–708. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, Amaya F, Constantin CE, Brenner GJ, Rubino T, Michalski CW, Marsicano G, Monory K, Mackie K, Marian C, Batkai S, Parolaro D, Fischer MJ, Reeh P, Kunos G, Kress M, Lutz B, Woolf CJ, Kuner R. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jhaveri M, Richardson D, Chapman V. Endocannabinoid metabolism and uptake: novel targets for neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:624–632. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Després JP, Golay A, Sjöström Lars. Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2121–2134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaal LFV, Rissanen AM, Scheen AJ, Ziegler O, Rössner S. Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet. 2005;365:1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pi-Sunyer FX, Aronne LJ, Heshmati HM, Devin J, Rosenstock J. Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients. JAMA. 2005;295:761–775. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheen AJ, Finer N, Hollander P, Jensen MD, Gaal LFV. Efficacy and tolerability of rimonabant in overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2006;368:1660–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaal LFV, Scheen AJ, Rissanen AM, Rössner S, Hanotin C, Ziegler O. Long-term effect of CB1 blockade with rimonabant on cardiometabolic risk factors: two year results from the RIO-Europe Study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1761–1771. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreira FA, Grieb M, Lutz B. Central side-effects of therapies based on CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists: focus on anxiety and depression. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owens B. Drug development: The treasure chest. Nature. 2015;525:S6–S8. doi: 10.1038/525S6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deutsch DG, Ueda N, Yamamoto S. The fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:201–210. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Structure and function of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:411–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson M, Contreras JA, Hellman U, Tornqvist H, Holm C. cDNA cloning, tissue distribution, and identification of the catalytic triad of monoglyceride lipase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27218–27223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blankman LJ, Simon MG, Cravatt FB. A comprehensive profile of brain enzymes that hydrolyze the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Chem Biol. 2007;14:1347–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makara JK, Mor M, Fegley D, Szabo SI, Kathuria S, Astarita G, Duranti A, Tontini A, Tarzia G, Rivara S, Freund TF, Piomelli D. Selective inhibition of 2-AG hydrolysis enhances endocannabinoid signaling in hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1139–1141. doi: 10.1038/nn1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blankman JL, Cravatt BF. Chemical probes of endocannabinoid metabolism. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:849–871. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.006387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler CJ. The potential of inhibitors of endocannabinoid metabolism for drug development: A critical review. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;231:95–128. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20825-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohnz RA, Nomura DK. Chemical approaches to therapeutically target the metabolism and signaling of the endocannabinoid 2-AG and eicosanoids. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:6859–6869. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00047a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Labar G, Wouters J, Lambert DM. A review on the monoacylglycerol lipase: at the interface between fat and endocannabinoid signalling. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:2588–2607. doi: 10.2174/092986710791859414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulvihill MM, Nomura DK. Therapeutic potential of monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors. Life Sci. 2013;92:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuo W, Leleu-Chavain N, Spencer J, Sansook S, Millet R, Chavatte P. Therapeutic potential of fatty acid amide hydrolase, monoacylglycerol lipase, and N-acylethanolamine acid amidase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2017;60:4–46. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long JZ, Li W, Booker L, Burston JJ, Kinsey SG, Schlosburg JE, Pavon FJ, Serrano AM, Selley DE, Parsons LH, Lichtman AH, Cravatt BF. Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura DK, Morrison BE, Blankman JL, Long JZ, Kinsey SG, Marcondes MCG, Ward AM, Hahn YK, Lichtman AH, Conti B, Cravatt BF. Endocannabinoid hydrolysis generates brain prostaglandins that promote neuroinflammation. Science. 2011;334:809–813. doi: 10.1126/science.1209200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao Z, Mulvihill MM, Mukhopadhyay P, Xu H, Erdelyi K, Hao E, Holovac E, Hasko G, Cravatt BF, Nomura DK, Pacher P. Monoacylglycerol lipase controls endocannabinoid and eicosanoid signaling and hepatic injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:808–817. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costola-de-Souza C, Ribeiro A, Ferraz-de-Paula V, Calefi AS, Aloia TP, Gimenes-Junior JA, Almeida VId, Pinheiro ML, Palermo-Neto J. Monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) inhibition attenuates acute lung injury in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fowler CJ. The potential of inhibitors of endocannabinoid metabolism for drug development: A critical review. In: Pertwee RG, editor. Endocannabinoids. Vol. 231. 2015. pp. 95–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CM, Farde L. Using positron emission tomography to facilitate CNS drug development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phelps ME. Positron emission tomography provides molecular imaging of biological processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:9226–9233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fowler JS, Wolf AP. Working against time: Rapid radiotracer synthesis and imaging the human brain. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:181–188. doi: 10.1021/ar960068c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willmann JK, Bruggen Nv, Dinkelborg LM, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:591–607. doi: 10.1038/nrd2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rusjan PM, Wilson AA, Mizrahi R, Boileau I, Chavez SE, Lobaugh NJ, Kish SJ, Houle S, Tong J. Mapping human brain fatty acid amide hydrolase activity with PET. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:407–414. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu P, Hamill TG, Chioda M, Chobanian H, Fung S, Guo Y, Chang L, Bakshi R, Hong Q, Dellureficio J, Lin LS, Abbadie C, Alexander J, Jin H, Mandala S, Shiao LL, Li W, Sanabria S, Williams D, Zeng Z, Hajdu R, Jochnowitz N, Rosenbach M, Karanam B, Madeira M, Salituro G, Powell J, Xu L, Terebetski JL, Leone JF, Miller P, Cook J, Holahan M, Joshi A, O’Malley S, Purcell M, Posavec D, Chen TB, Riffel K, Williams M, Hargreaves R, Sullivan KA, Nargund RP, DeVita RJ. Discovery of MK-3168: A PET tracer for imaging brain fatty acid amide hydrolase. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:509–513. doi: 10.1021/ml4000996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joshi A, Li W, Sanabria S, Holahan M, Purcell M, Declercq R, Depre M, Bormans G, Van Laere K, Hamill T. Translational studies with [11C]MK-3168, a PET tracer for fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) J Nucl Med. 2012;53:397. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hicks JW, Parkes J, Tong J, Houle S, Vasdev N, Wilson AA. Radiosynthesis and ex vivo evaluation of [11C-carbonyl]carbamate- and urea-based monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors. Nucl Med Biol. 2014;41:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L, Mori W, Cheng R, Yui J, Rotstein BH, Fujinaga M, Hatori A, Vasdev N, Zhang MR, Liang SH. A novel class of sulfonamido [11C-carbonyl]-labeled carbamates and ureas as radiotracers for monoacylglycerol lipase. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:4. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C, Placzek MS, Van de Bittner GC, Schroeder FA, Hooker JM. A novel radiotracer for imaging monoacylglycerol lipase in the brain using positron emission tomography. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7:484–489. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L, Mori W, Cheng R, Yui J, Hatori A, Ma L, Zhang Y, Rotstein BH, Fujinaga M, Shimoda Y, Yamasaki T, Xie L, Nagai Y, Minamimoto T, Higuchi M, Vasdev N, Zhang MR, Liang SH. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of sulfonamido-based [11C-carbonyl]-carbamates and ureas for imaging monoacylglycerol lipase. Theranostics. 2016;6:1145–1159. doi: 10.7150/thno.15257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahamed M, Attili B, van Veghel D, Ooms M, Berben P, Celen S, Koole M, Declercq L, Savinainen JR, Laitinen JT, Verbruggen A, Bormans G. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of [11C]MA-PB-1 for in vivo imaging of brain monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) Eur J Med Chem. 2017;136:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Fujinaga M, Cheng R, Yui J, Shimoda Y, Rotstein BH, Zhang Y, Vasdev N, Zhang MR, Liang SH. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of a 11C-labeled piperidin-4-yl azetidine diamide for imaging monoacylglycerol lipase. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1044. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye XY, Chen SY, Wu S, Yoon DS, Wang H, Hong Z, O’Connor SP, Li J, Li JJ, Kennedy LJ, Walker SJ, Nayeem A, Sheriff S, Camac DM, Ramamurthy V, Morin PE, Zebo R, Taylor JR, Morgan NN, Ponticiello RP, Harrity T, Apedo A, Golla R, Seethala R, Wang M, Harper TW, Sleczka BG, He B, Kirby M, Leahy DK, Hanson RL, Guo Z, Li YX, DiMarco JD, Scaringe R, Maxwell B, Moulin F, Barrish JC, Gordon DA, Robl JA. Discovery of clinical candidate 2-((2S,6S)-2-phenyl-6-hydroxyadamantan-2-yl)-1-(3′-hydroxyazetidin-1-yl)ethanone [BMS-816336], an orally active novel selective 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2017;60:4932–4948. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desroy N, Housseman C, Bock X, Joncour A, Bienvenu N, Cherel L, Labeguere V, Rondet E, Peixoto C, Grassot JM, Picolet O, Annoot D, Triballeau N, Monjardet A, Wakselman E, Roncoroni V, Le Tallec S, Blanque R, Cottereaux C, Vandervoort N, Christophe T, Mollat P, Lamers M, Auberval M, Hrvacic B, Ralic J, Oste L, van der Aar E, Brys R, Heckmann B. Discovery of 2-[[2-ethyl-6-[4-[2-(3-hydroxyazetidin-1-yl)-2-oxoethyl]piperazin-1-yl]-8-methylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl]methylamino]-4-(4-fluorophenyl)thiazole-5-carbonitrile (GLPG1690), a first-in-class autotaxin inhibitor undergoing clinical evaluation for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Chem. 2017;60:3580–3590. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johansson A, Löfberg C, Antonsson M, von Unge S, Hayes MA, Judkins R, Ploj K, Benthem L, Lindén D, Brodin P, Wennerberg M, Fredenwall M, Li L, Persson J, Bergman R, Pettersen A, Gennemark P, Hogner A. Discovery of (3-(4-(2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3. 3]heptan-6-ylmethyl)phenoxy)azetidin-1-yl)(5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methanone (AZD1979), a melanin concentrating hormone receptor 1 (MCHr1) antagonist with favorable physicochemical properties. J Med Chem. 2016;59:2497–2511. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butler CR, Beck EM, Harris A, Huang Z, McAllister LA, am Ende CW, Fennell K, Foley TL, Fonseca K, Hawrylik SJ, Johnson DS, Knafels JD, Mente S, Stephen Noell G, Pandit J, Phillips TB, Piro JR, Rogers BN, Samad TA, Wang J, Wan S, Brodney MA. Azetidine and piperidine carbamates as efficient, covalent inhibitors of monoacylglycerol lipase. J Med Chem. 2017;60:9860–9873. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patwardhan NN, Morris EA, Kharel Y, Raje MR, Gao M, Tomsig JL, Lynch KR, Santos WL. Structure-activity relationship studies and in vivo activity of guanidine-based sphingosine kinase inhibitors: discovery of SphK1- and SphK2-selective inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2015;58:1879–1899. doi: 10.1021/jm501760d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hernandez-Torres G, Cipriano M, Heden E, Bjorklund E, Canales A, Zian D, Feliu A, Mecha M, Guaza C, Fowler CJ, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Lopez-Rodriguez ML. A reversible and selective inhibitor of monoacylglycerol lipase ameliorates multiple sclerosis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:13765–13770. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cravatt BF, Wright AT, Kozarich JW. Activity-based protein profiling: from enzyme chemistry to proteomic chemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:383–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schalk-Hihi C, Schubert C, Alexander R, Bayoumy S, Clemente JC, Deckman I, DesJarlais RL, Dzordzorme KC, Flores CM, Grasberger B, Kranz JK, Lewandowski F, Liu L, Ma H, Maguire D, Macielag MJ, McDonnell ME, Mezzasalma Haarlander T, Miller R, Milligan C, Reynolds C, Kuo LC. Crystal structure of a soluble form of human monoglyceride lipase in complex with an inhibitor at 1. 35 A resolution. Protein Sci. 2011;20:670–683. doi: 10.1002/pro.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. Extra precision glide: Docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sherman W, Day T, Jacobson MP, Friesner RA, Farid R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. J Med Chem. 2006;49:534–553. doi: 10.1021/jm050540c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu K, Borrelli KW, Greenwood JR, Day T, Abel R, Farid RS, Harder E. Docking covalent inhibitors: a parameter free approach to pose prediction and scoring. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54:1932–1940. doi: 10.1021/ci500118s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harder E, Damm W, Maple J, Wu C, Reboul M, Xiang JY, Wang L, Lupyan D, Dahlgren MK, Knight JL, Kaus JW, Cerutti DS, Krilov G, Jorgensen WL, Abel R, Friesner RA. OPLS3: A force field providing broad coverage of drug-like small molecules and proteins. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016;12:281–296. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Still WC, Tempczyk A, Hawley RC, Hendrickson T. Semianalytical treatment of solvation for molecular mechanics and dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6127–6129. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waterhouse RN. Determination of lipophilicity and its use as a predictor of blood-brain barrier penetration of molecular imaging agents. Mol Imaging Biol. 2003;5:376–389. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel S, Gibson R. In vivo site-directed radiotracers: a mini-review. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:805–815. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pike VW. Considerations in the development of reversibly binding PET radioligands for brain Imaging. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:1818–1869. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160418114826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals 107 — Partition Coefficient (n-Octanol/water): Shake Flask Method. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD); Paris: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilson AA, Garcia A, Parkes J, Houle S, Tong J, Vasdev N. [11C]CURB: Evaluation of a novel radiotracer for imaging fatty acid amide hydrolase by positron emission tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson AA, Hicks JW, Sadovski O, Parkes J, Tong J, Houle S, Fowler CJ, Vasdev N. Radiosynthesis and evaluation of [11C-carbonyl]-labeled carbamates as fatty acid amide hydrolase radiotracers for positron emission tomography. J Med Chem. 2013;56:201–209. doi: 10.1021/jm301492y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]