Abstract

This article traces the development of acyclic cucurbit[n]uril-type receptors with a focus on work from the Isaacs group. First, we describe the synthesis of methylene bridged glycoluril dimers capped with aromatic sidewalls which allowed us to probe the interconversion of the S- and C-shaped dimers which is a fundamental step in CB[n] formation. The C-shaped compounds were found to undergo discrete self-assembly (dimerization) in both water and organic solvents which lead us to investigate multicomponent self-sorting systems. We supressed the self-association of 8 by electrostatic repulsion in the putative dimer which allowed expression of its innate molecular recognition properties toward methylene blue and related planar cationic dyes. Longer glycoluril oligomers (trimer – hexamer, acyclic decamer) were prepared by starving the CB[n]-forming reaction of formaldehyde. The longer oligomers (e.g. 15 and 16) bind to alkylammonium ions in water ≈ 100-fold weaker than macrocyclic CB[n] highlighting the high preorganization of the acyclic but polycyclic framework. We prepared a wide variety of acyclic CB[n] compounds (wall variants, solubilizing group variants, linker variants) based on glycoluril trimer and tetramer. In particular, 26 and 27 have been shown to possess a wide variety of chemically and biologically interesting functions. For example, 26 was used to formulate the insoluble drug Albendazole and treat mice bearing SK-OV-3 xenograft tumors. Compound 27 binds tightly to the neuromuscular blocking agents rocuronium, vecuronium, and cisatracurium and acts as an in vivo reversal agent for these compounds in anesthetized rats. Container 27 was also found to modulate the hyperlocomotive effect of rats that had been treated with methamphetamine. Finally, 38 has been used as a cross reactive component of sensor arrays that are capable of classifying and quantifying cancer related nitroamines and a range of over the counter drugs. Overall, the work demonstrates that acyclic CB[n]-type compounds are nicely pre-organized and therefore retain the essential aspects of the recognition properties of macrocyclic CB[n] but allow for more straightforward tailoring of structure and solubility that enables a variety of chemically and biologically important applications.

Keywords: cucurbit[n]urils, molecular clips, molecular recognition, preorganization, drug solubilization, reversal agents

1. Introduction

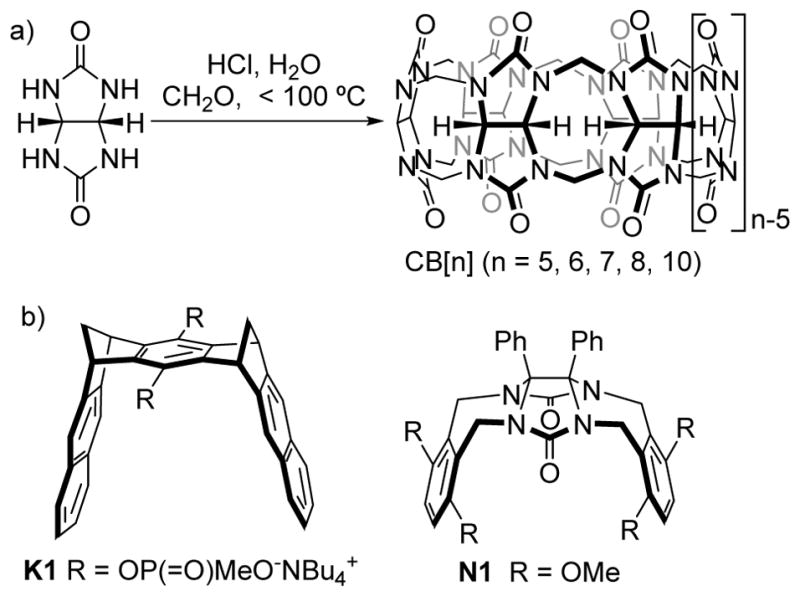

The use of glycoluril as a versatile building block for the creation of host molecules can be traced to the pioneering work of Mock who elucidated the structure of the cucurbit[6]uril (CB[6]) macrocycle which is prepared by the condensation of glycoluril and formaldehyde under strongly acidic conditions (Figure 1). The structure of CB[6] features two symmetry equivalent highly electrostatically negative ureidyl carbonyl portals which guard entry to a central hydrophobic cavity. Accordingly, CB[6] displays a high affinity toward alkanediammonium ions in aqueous solution due to a combination of ion-dipole interactions and the hydrophobic effect. In the intervening years, workers in the field have synthesized homologues and derivatives of macrocyclic CB[n] (n = 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15),[1] explored their fundamental properties and stimuli responsive molecular recognition events, and used them for advanced applications like biological and chemical sensing and separations, supramolecular materials, drug formulation and targeted delivery.[2] Given the availability of a large number of authoritative reviews of macrocyclic CB[n],[2] we instead focus herein on the synthesis, molecular recognition properties, and applications of acyclic – but preorganized –members of the CB[n] family of molecular containers with examples drawn largely from our laboratory.

Figure 1.

a) Synthesis of CB[n] and b) Structures of molecular clips K1 and N1.

Preorganization is one of the most important principles of supramolecular chemistry which states that “the more highly hosts and guests are organized for binding and low solvation prior to their complexation, the more stable will be their complexes.”[3] Host preorganization is most commonly achieved by macrocyclization[4] but can also be achieved in acyclic systems by careful conformational control. Prime examples of such acyclic but preorganized systems include molecular clips and tweezers popularized by Nolte (e.g. N1), Zimmerman, Klärner (e.g. K1), and others (Figure 1).[5] Of particular relevance to this review is the pioneering work of Nolte who attached substituted aromatic sidewalls to the curved and conformationally fixed glycoluril skeleton via conformationally biased seven membered rings to create molecular clips.[5b] Nolte elaborated these clips to create a variety of receptors including those that display induced fit, allostery, hierarchical assembly, and function as processive catalysts.[6] In this review, we focus on acyclic CB[n]-type receptors that feature glycoluril oligomers capped with aromatic termini that merge the favourable properties of CB[n] with those of molecular clips.

2. Acyclic CB[n]-Type Receptors

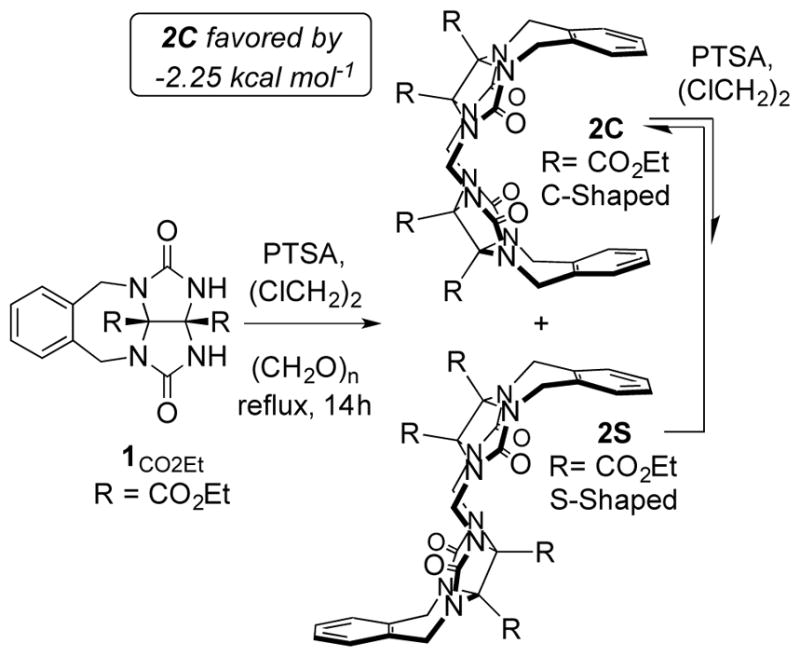

2.1. Systems Based on Methylene Bridged Glycoluril Dimers

When the Isaacs lab started working in the CB[n] field in 1998, a major issue was the poor aqueous solubility of CB[6]. Accordingly, we prepared CO2Et functionalized glycoluril with the goal of transforming it into a carboxylic acid derivative of CB[6] but were unsuccessful. To simplify and thereby better understand the synthetic process we prepared organic soluble, CO2Et functionalized glycoluril derivative 1CO2Et which is capped with an o-xylylene ring that limits the condensation reaction to the formation of the S- and C-shaped methylene bridged glycoluril dimers 2C and 2S (Figure 2) substructure which is the fundamental building block of CB[n]-type receptors. We prepared both organic (CO2Et substituted) and water soluble (CO2H substituted) methylene bridged glycoluril dimers with a range of aromatic walls and pendant functionality. We delineated the thermodynamic preference for the C-shaped diastereomers (>2.3 kcal mol−1) by measuring the ratio of 2C:2S at equilibrium during product resubmission experiments.[7] We also studied their self-assembly and molecular recognition processes as described below. Sindelar and co-workers have studied the formation of S- and C-shaped methylene bridged glycoluril dimers using unsubstituted glycoluril under aqueous acidic conditions and found similar preferences for the C-shaped diastereomer.[8]

Figure 2.

Preparation of methylene bridged glycoluril dimers.

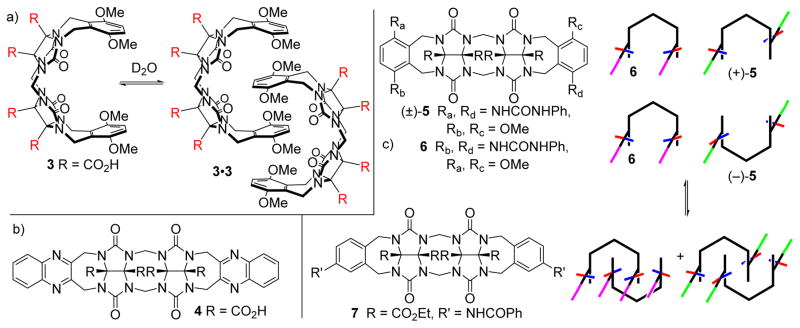

2.1.1. Self-Assembly Processes

Figure 3 shows the chemical structure of methylene bridged glycoluril dimers 3 – 7. The polycyclic ring system consisting of fused five, six, seven and eight membered rings adopts a well defined conformation where the aromatic sidewalls are roughly parallel and separated by ≈ 7 Å and the water solubilizing carboxylic acid groups are on the convex face. Accordingly, 3 undergoes dimerization in water (pD 7.4, 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer) due to π–π interactions and the hydrophobic effect to give 3•3 (Ka = 41666 M−1) as evidenced by 1H NMR, ITC, and analytical ultracentrifugation (Figure 3a).[9] The protonation state of the CO2H groups of 3 at pD 7.4 was not determined. Compound 4 with larger and more electron deficient aromatic sidewalls undergoes very tight dimerization in water (pD 7.4) and remains dimeric even at 95 °C.[10] Quite interestingly, we found that certain organic soluble (e.g. CDCl3) methylene bridged glycoluril dimers (e.g. (±)-5 and 6) also undergo dimerization in organic solvents driven by a combination of π–π interactions and two H-bonds between the ArNH(C=O)R sidearms (Figure 3c).[11] 1H NMR spectroscopy clearly show the presence of internal and external aromatic rings that are in slow exchange on the chemical shift timescale which indicates high stability of the dimeric assemblies (e.g. 52, 62). It is noteworthy that although (±)-5 is chiral and racemic, the dimeric assembly (+)-5•(−)-5 is a well defined heterochiral assembly (X-ray and 1H NMR) due to the combined geometrical constraints of the supporting π–π and H-bonding interactions. Even more interesting was the behaviour of a mixture of molecular clips 5 – 7. We found that these compounds underwent a narcissistic self-sorting process with the clean formation of 52, 62, and 72. The high fidelity of self-sorting is driven by need to simultaneously satisfy the geometrical constraints of π–π interactions and maximize the number of H-bonds; the hypothetical heterodimers sacrifice one or more H-bonds. This work represented our entry into the area of self-sorting which was further delineated in a series of papers that spanned organic solvents and water, narcissistic and social self-sorting, kinetic versus thermodynamically controlled sorting, and the creation of rudimentary self-sorting networks and cascades.[11a,11b,10,12a,12b,11c,12c,12d] The key outcome of the work, which was counter-intuitive at the time, was that many of the well known synthetic supramolecular host and self-assembly systems contained sufficient information encoded in their molecular structures to allow them to selectively engage their partner even within complex mixtures. This work in self-sorting can be seen as an intellectual counterpart of the current thrust area of systems chemistry,[13] which aims for controlled levels of interactions between sets of molecules. Although these self-association (dimerization) processes proved to be quite interesting in their own right they prevented the expression of the inherent host-guest recognition processes of the host.

Figure 3.

Self-assembly and self-sorting processes of methylene bridged glycoluril dimers 3 – 7.

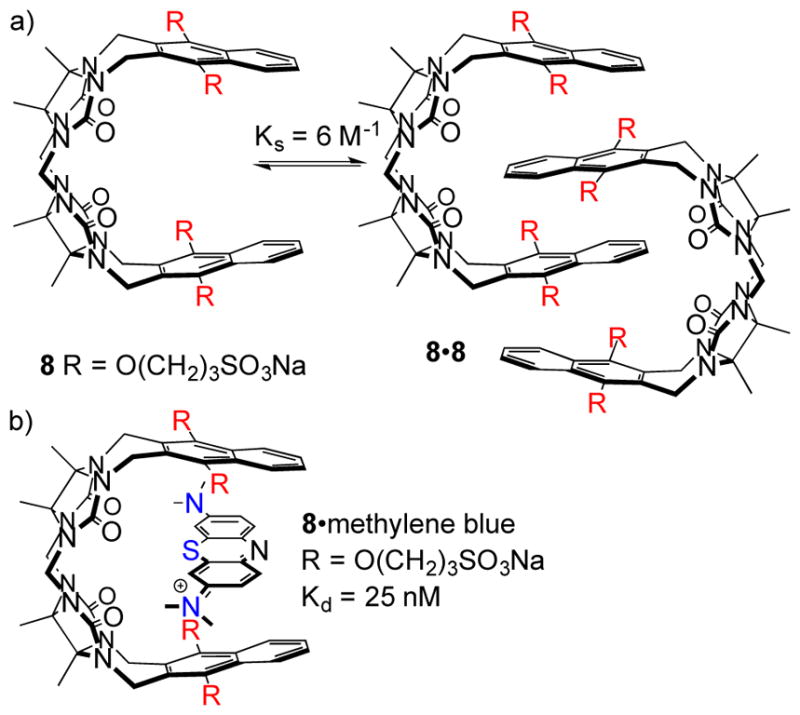

2.1.2. Molecular Recognition Processes

As mentioned above, the self-association of methylene bridged glycoluril dimers is an impediment to their use as molecular hosts (Figure 4). Recently, as part of our studies of drug solubilisation and delivery (vide infra), Isaacs, Sindelar and co-workers prepared methylene bridged glycoluril dimers 8 and its benzene analogue 9 as control compounds. Unexpectedly, we found that 8 and 9 function as solubilizing agents for camptothecin and PBS-1086.[14] We traced this unexpected success to supressed self-association abilities of 8 and 9 (Ks = 6 and 12 M−1, respectively). We attribute this unexpected result to: 1) the presence of the solubilizing groups on the aromatic sidewalls of 8 and 9 (cf. convex face disposition in 2C), and 2) the fully deprotonated nature of the SO3− solubilizing groups at physiological pH. Both factors result in a buildup of unfavourable electrostatic interactions which destabilize the putative dimeric assembly 82.[14] Given that 8 remained monomeric in solution at mM concentrations we, in collaboration with Sindelar, sought to define its molecular recognition properties toward representative cationic guests including dye molecules. We find that 8 displays high affinity and selectivity for planar and cationic aromatic guests including dyes like methylene blue, azure A and naphthalene diimides.[15] Electrostatic effects display a dominant role in the recognition process whereby ion-ion and ion-dipole interactions occur between cationic guest and the hosts C=O and SO3− groups and cation-π interactions occurs between the cationic aromatic ring (e.g. methylene blue) of the guest and dialkoxynapthalene walls of 8. The affinity of the 8•methylene blue complex (Ka = 3.9 × 107 M−1) is sufficient to allow the use of 8 as an agent to destain U87 cells that had previously been stained with methylene blue.

Figure 4.

a) Structure of 8 and its putative dimer, and b) illustration of the geometry and driving forces for formation of the 8•methylene blue complex.

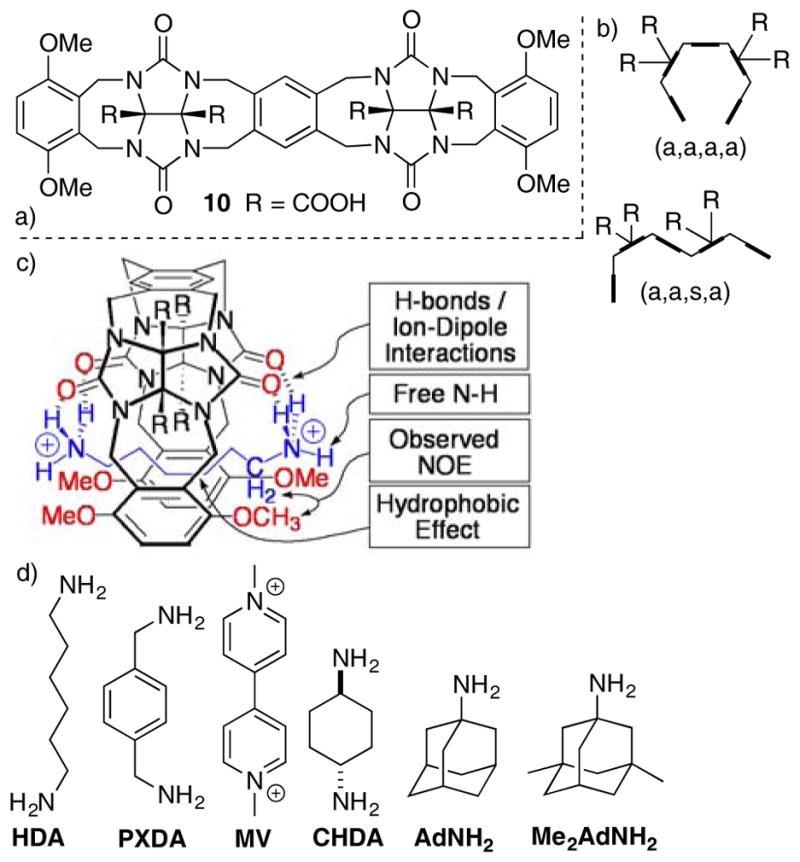

2.2. An Elaborated Molecular Clip That Functions as an Acyclic CB[n] Congener

In concert with our studies of compounds that feature the methylene bridged glycoluril dimer substructure we also prepared compound 10 that contains alternating aromatic and glycoluril building blocks (Figure 5) which can be seen as the covalent connection of two Nolte-type molecular clips.[16] Based on the precedent of Nolte[5b] and on molecular modelling we believe that 10 predominantly adopts the (a,a,a,a)-10 conformation although the higher energy (a,a,s,a)-10 conformation was observed in the x-ray structure of due to its propensity for dimerization (Figure 5b). We studied the binding of 10 toward a panel of (di)ammonium ions (HDA, PXDA, CHDA, AdNH2, Me2AdNH2) that are typical for CB[n] hosts and determined that 10 displays highest affinity toward the narrow hexane diammonium (Ka = 1.52 × 104 M−1) ion; the wider p-xylylene diammonium ion (Ka = 496 M−1) is bound significantly less tightly despite the potential for π–π interactions. For comparison, Mock reported the CB[6]•HDA has Ka = 2.8 × 106 M−1 which is only two order of magnitude larger than 10•HDA.[17] The length based selectivity and the sensitivity of the Ka values of CB[n]•guest complexes to metal ion concentration are retained by 10.[18] In combination, these results provided a first clue that suitably preorganized acyclic CB[n]-type receptors could recapitulate some of the desirable recognition properties of macrocyclic CB[n].

Figure 5.

a) Chemical structure of 10, b) schematic depiction of its (a,a,a,a) and (a,a,s,a) conformers, c) three dimensional representation of the 10•HDA complex, d) structures of common guests for CB[n]-type receptors.

2.3. Methylene Bridged Glycoluril Oligomers

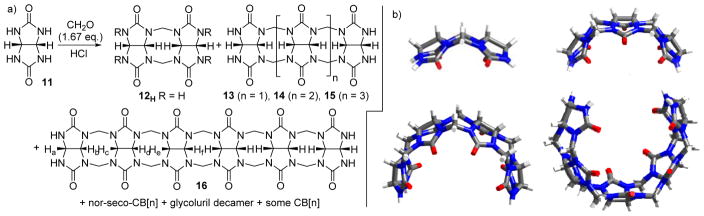

The macrocyclization reaction between glycoluril and formaldehyde to deliver CB[n] has a natural stoichiometry of 1:2 which reflects the fact that glycoluril is a tetrafunctional monomer whereas formaldehyde is a difunctional monomer. We wondered if CB[n] would remain the dominant product if we starved the reaction of formaldehyde or whether intermediates along the mechanistic pathway to CB[n] would be obtained. Accordingly, Wei-Hao Huang conducted the reaction between glycoluril (11) and 1.67 equiv. formaldehyde and obtained glycoluril oligomers (dimer – hexamer, 12 – 16), acyclic glycoluril decamer (±)-17, and macrocyclic nor-seco-CB[n] (Figure 6).[19] Figure 6b shows the x-ray crystal structures of 12 – 15 which demonstrates their overall C-shape which is required for macrocyclization to CB[n]. Glycoluril hexamer has been used as a versatile building block for the preparation of monofunctionalized derivatives of CB[6] and CB[7].[20]

Figure 6.

a) Synthesis of methylene bridged glycoluril oligomers and nor-seco-CB[n], and b) x-ray crystal structures of 12H – 16.

With a series of glycoluril oligomers in hand, we sought to quantify the influence oligomer length and macrocyclization on the binding constants toward common ammonium ion guests (Table 1).[21] Hosts 15 and 16 display slow kinetics of exchange on the chemical shift timescale for guests HDA and PXDA despite the acyclic nature of the host. Table 1 presents the measured binding constants toward 14 – 16 and also toward CB[6] and CB[7]. Several trends are noteworthy. First, the binding constant for a given guest increases as the length of glycoluril oligomer increases from tetramer to hexamer. Second, for guests that do not exceed the capacity of CB[n], the binding toward hexamer 16 is only approximately 102-fold weaker than towards CB[6] or CB[7]. Third, pentamer 15 and hexamer 16 are potent hosts toward adamantane derived guests AdNH2 and Me2AdNH2 which shows that glycoluril oligomers can flex their backbone to accommodate guests that would be too large for their macrocyclic counterparts. These results show that glycoluril oligomers longer than trimer maintain the convergence of ureidyl C=O groups that impart affinity toward organic cations whereas pentamer and hexamer appear to benefit from a cavity effect perhaps attributable to encapsulated high energy H2O molecules.[22a,2a,22b]

Table 1.

Binding constants (Ka/106 M−1) measured for the complexes between hosts CB[6], CB[7], and 14 – 16 and guests HDA, PXDA, CHDA, AdNH2, and Me2AdNH2.

| Guest[a] | 14 | 15 | 16 | CB[6] | CB[7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDA | 0.0056 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 450 | 90 |

| PXDA | 0.015 | 1.2 | 22 | 0.00055 | 1800 |

| CHDA | – | 0.027 | 0.68 | 1.4 | 23 |

| AdNH2 | – | 1.1 | 18 | nb | 4.2×106 |

| Me2AdNH2 | – | 0.61 | 6.0 | nb | 0.025 |

nb = no binding.

– = not measured.

Another clue toward the great potential of acyclic CB[n]-type receptors came from our study of (±)-17. (±)-17 features two glycoluril pentamers that are connected by a single CH2-bridge.[19e] We performed qualitative 1H NMR binding studies and found that (±)-17 formed complexes with some standard CB[n] guests (e.g. HDA, PXDA, CHDA, AdNH2, Me2AdNH2, and methyl viologen (MV)) in pure D2O. Interestingly, when 100 mM alkali metal cations (Li+, Na+, K+) was added to a solution of (±)-17 in D2O a well resolved 1H NMR spectrum with some dramatically upfield shifted resonances was observed. Figure 7b shows the x-ray crystal structure of the obtained assembly which can be formulated as the heterochiral dimer of decamers (+)-17•(−)-17•Na6. In this assembly, each molecule of 17 assumes a helical conformation which threads through the hydrophobic cavity of the opposing molecule and is reinforced by ion-dipole interactions between the six Na+ ions and two or more ureidyl C=O groups on each strand of 17. This assembly is remarkably tight and persists down to 100 μM concentration. This result was eye opening for us because it showed the glycoluril derived systems and in particular acyclic CB[n]-type receptors could, in addition to the tight and selective binding of organic cations which is protein mimetic, undergo metal ion triggered folding and assembly which is more reminiscent of the behaviour of nucleic acids.

Figure 7.

a) Chemical structure of 17. b) Cross eyed stereoview of the x-ray crystal structure of (+)-17•(−)-17•Na6. Color code: C, grey; H, white; N, blue; O, red; Na, yellow.

2.4. Acyclic CB[n]-type Receptors

In combination, the above results suggested that glycoluril oligomers capped with o-xylylene rings might combine the advantageous features of CB[n] hosts with the potential for functionalization and the ability to engage in π–π interactions with guests. This line of inquiry has been pursued by the groups of Isaacs and Sindelar both alone and in collaboration based on central glycoluril trimer and tetramer building blocks.

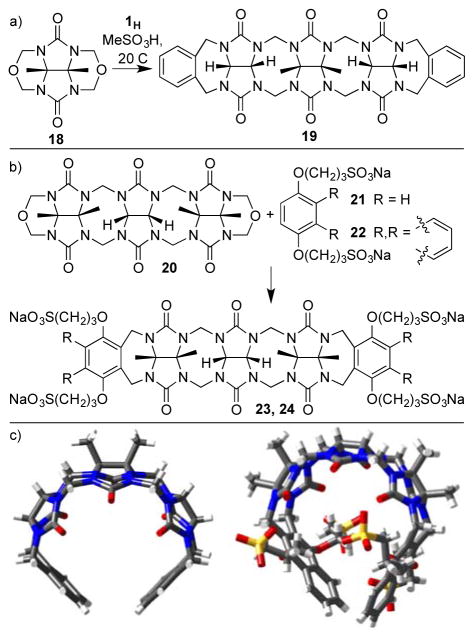

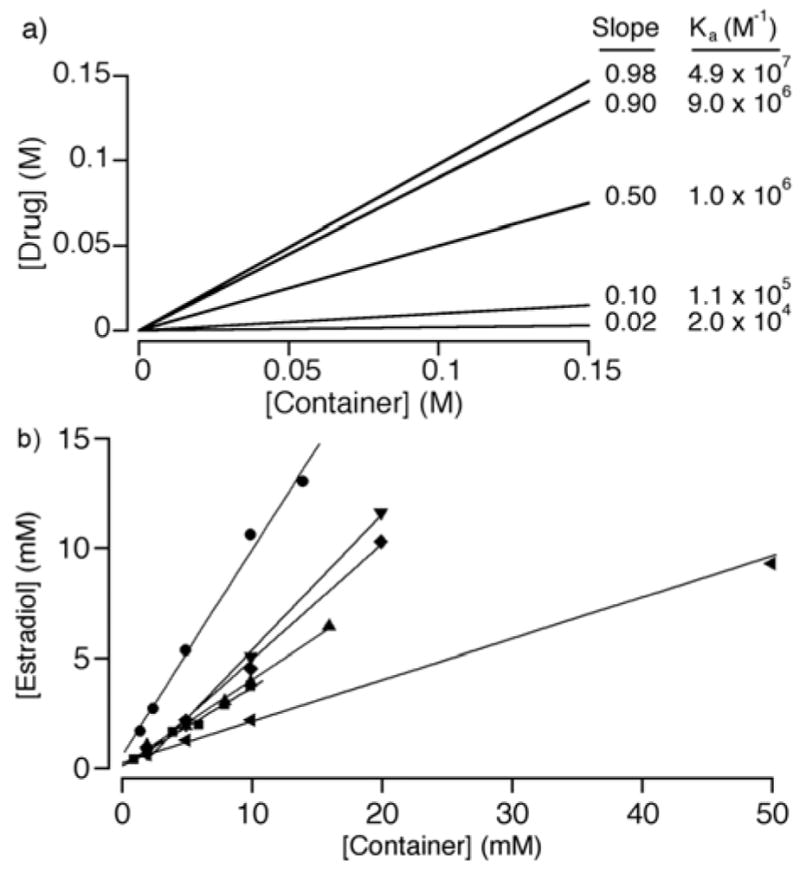

2.4.1. Acyclic CB[n]-Type Receptors Based on Glycoluril Trimer

Two different synthetic methods toward the preparation of acyclic CB[n]-type receptors based on glycoluril trimer have been reported. For example, Sindelar’s group reported the condensation reaction of 1H with glycoluril cyclic ether 18 in MeSO3H at 20 °C and was able to isolate 19 in 34% yield (Figure 8).[23] In contrast, Isaacs and Sindelar reported the condensation of glycoluril trimer (20) with aromatic sidewalls 21 and 22 in TFA/Ac2O (1:1) at 70 °C to give 23 and 24 in 48 and 59% yield, respectively. The aqueous solubility of 24 (102 mM) and 23 (336 mM) which are substituted with four SO3− solubilizing groups are significantly higher than that of 19.[14] The x-ray crystal structures of 23 and 24 are shown in Figure 8c which illustrates how the glycoluril oligomer creates a hydrophobic cavity that is further defined by the aromatic sidewalls. Compound 23 was shown to bind to MV with Ka = 75000 M−1 in D2O, whereas 24 was determined to bind to various pharmaceutical agents including PBS-1086 (Ka = 36000 M−1) and β-estradiol (Ka = 14000 M−1).

Figure 8.

a) Synthesis of 19, 23, and 24, and b) x-ray crystal structures of 19 and 24.

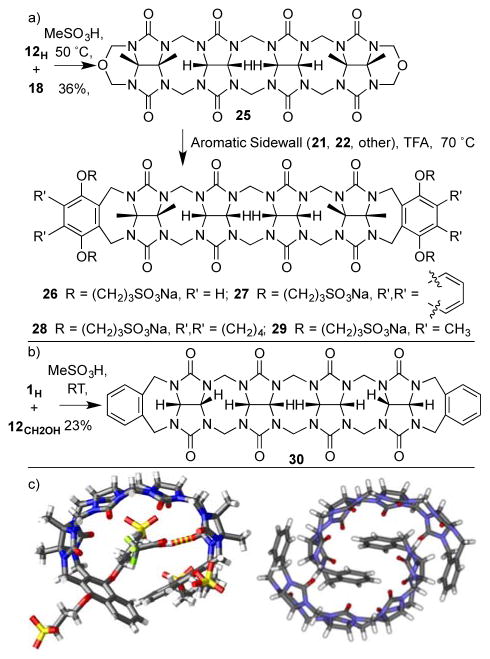

2.4.2. Synthesis of Acyclic CB[n]-Type Receptors Based on Glycoluril Tetramer

The groups of Isaacs and Sindelar have separately reported procedures to access acyclic CB[n]-type receptors based on glycoluril tetramer. The Isaacs group uses a building block approach (Figure 9a).[24] We prepare glycoluril bis(cyclic ether) 18 on the 719 gram scale in two steps by condensation reactions of butanedione, urea, and paraformaldehyde. Glycoluril dimer 12H can be prepared on the 334 gram scale from glycoluril and paraformaldehyde in a single step. The critical C-shaped glycoluril tetramer 25 is prepared on the 76 gram scale by condensation of 18 and 12H in anhydrous MeSO3H. Finally, the aromatic sidewalls are installed by a double electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction between 25 and 21 (22) to give 26 (27) in 40 and 30% yield, respectively. This efficient large scale synthesis enables potential real world application of 26 and 27 as described below. Sindelar pursued a different approach involving the condensation of 1H with glycoluril dimer tetrol 12CH2OH in CH3SO3H to deliver 30 in 23% yield.[25] Hosts 26 (356 mM) and 27 (18 mM) which contain SO3− solubilizing groups are highly soluble in water whereas unsubstituted 30 is poorly soluble. The x-ray crystal structures of 27 and 30 are shown in Figure 9c which illustrate their overall C-shape. Interestingly, 30 undergoes dimerization in the crystal driven by π–π interactions between aromatic sidewalls and van der Waals interactions between the glycoluril oligomers.

Figure 9.

a, b) Synthesis of 26 – 30, and c) x-ray crystal structures of 27 and 30.

2.4.2. Applications of Acyclic CB[n]-type Receptors

In this section we detail the use of acyclic CB[n]-type receptors in biological and chemical applications.

2.4.2.1. Use of Acyclic CB[n]-type Receptors as Solubilizing Excipients for Insoluble Drugs

Among the known classes of molecular container compounds, the cyclodextrins have found the broadest use in everyday real world applications. For example, hydroxypropyl-β-CD is generally regarded as safe by the US FDA and is used as an excipient for the formulation of insoluble drugs administered to humans.[26] Currently, the sulfonated β-CD derivative (SBE-β-CD)[27] is a popular solubilizing excipient and is currently being used to formulate at least 9 drugs for humans including amiodarone, voriconazole, ziprasidone, melphalan, and posaconazole.[28] Highly water soluble cyclodextrins function well in this application because they bind to insoluble drugs to form soluble cyclodextrin•drug complexes. Accordingly, we sought to evaluate the potential of acyclic CB[n]-type receptors in this application area.

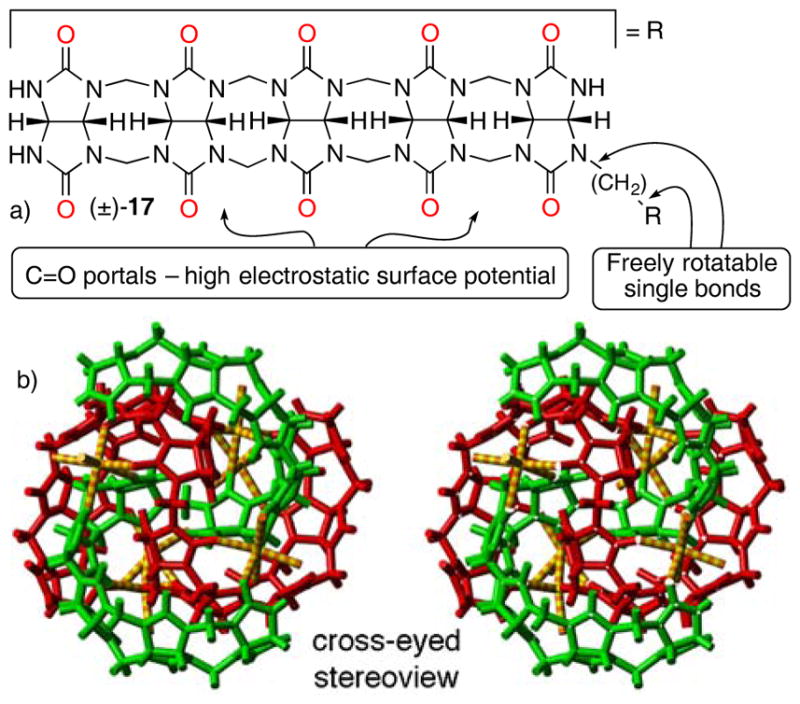

To evaluate the efficiency of a given molecular container as a solubilizing excipient for insoluble drugs it is necessary to create a phase solubility diagram (PSD, Figure 10a). A phase solubility diagram is a plot of concentration of insoluble drug in solution versus container concentration. For idealized 1:1 container:drug binding, linear PSDs are obtained and obey equation 1 where Ka is the container•drug binding constant, S0 is the inherent drug solubility and slope is the slope of the PSD. Figure 10a shows simulated PSDs for a drug with inherent solubility of 1 μM that forms container•drug complexes with five different Ka values from 2 × 104 to 4.9 × 107 M−1. To achieve a PSD slope of 0.50, which means the container is a good solubilizer, requires a Ka value of 1/S0. To nicely solubilize a drug of 1 μM (100 μM) requires a Ka of 106 (104) M−1. Accordingly, the higher binding constants of CB[n]-type versus cyclodextrins toward their guests suggests that acyclic CB[n]-type receptors may be more successful solubilizing excipients for very poorly soluble drugs.

Figure 10.

a) Simulated phase solubility diagram for a drug with 1 μM inherent solubility and different Ka values, b) PSDs constructed for estradiol with containers 26, ■; 27, ●; 28, ◆; 29, ▼; 38, ▲; and HP-β-CD, ◀.

| (1) |

In 2014, we reported the solubilisation of 19 different drugs by five acyclic CB[n] and HP-β-CD as comparator.[24c] Figure 10b presents the PSDs created for the drug estradiol which illustrates the large slope values achieve with all five acyclic CB[n] relative to HP-β-CD. The full data set allowed us to make some generalizations: 1) 27 is our most potent container, 2) acyclic CB[n] are excellent solubilizing agents for steroids, 3) by virtue of their aromatic walls acyclic CB[n] are good solubilizers for insoluble drugs containing aromatic rings, and 4) acyclic CB[n] are more potent receptors than HP-β-CD which translates into larger PSD slopes and more efficient solubilization. Macrocyclic CB[n] have also been considered as agents to formulate drugs;[29] we have not performed an explicit comparison of acyclic CB[n] with macrocyclic CB[n] due to the low solubility of CB[n]. The ability of 26 and 27 to act as solubilizing agents for carbon nanotubes was demonstrated in collaboration with Prof. YuHuang Wang.[30]

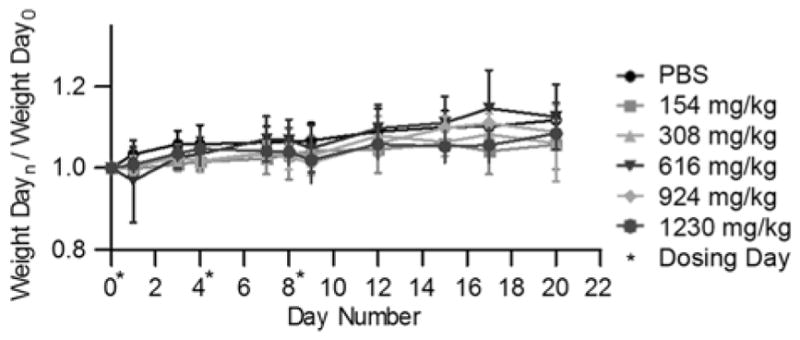

After having established the outstanding solubilisation abilities of 26 and 27 we decided to perform in vitro and in vivo toxicity studies to verify their biocompatibility.[24b,31] Accordingly, we performed complementary cell viability (MTS) and cell death (Adenylate Kinase release) assays with container 26 alone and did not observe significant toxicity up to 10 mM (2.5 mM) toward HepG2, HEK293, and THP-1 cells. Ex-vivo neuro-, myo-, and cardio-toxicity and assays for 27 were performed by Prof. Nial Wheate’s group.[32] To assess the mutagenicity of 26 and 27 we performed the reverse mutation assay (Ames test) using different strains that could detect base pair mutations and frameshift mutations using concentrations up to 1 mM.[31,33] The number of revertant colonies did not exceed double those observed for solvent control which is the standard for lack of mutagenicity. We also tested whether 26 and 27 inhibit the hERG ion channel by patch clamp experiments using CHO cells.[31,33] The hERG ion channel is essential for cardiac repolarization and compounds that inhibit it cannot be taken forward in the drug discovery process. Containers 26 and 27 show no evidence of hERG ion channel inhibition up to 25 mM which paves the way for their further development. Finally, we performed maximum tolerated dose studies for 26 and 27 in female Swiss Webster mice and did not observe any significant difference in the weight or the health status of the animals treated with up to 1230 mg/kg and 203 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 11).[24b,31] We have found that the containers are largely excreted unchanged in the urine of the animals over 1 hour.[34,31] Overall, these results strongly suggested that 26 and 27 had excellent biocompatibility and should be developed further for practical applications. Macrocyclic CB[n] are also well tolerated in animals.[35]

Figure 11.

Maximum tolerated dose study performed for container 26. Female Swiss Webster mice (n = 5 per group) were dosed via the tail vein on days 0, 4 and 8 (*, dosing day) with different concentrations of 26 or phosphate buffered saline. The total amount of 26 per kg of body weight is indicated. The normalized average weight change per study group (n = 5) is indicated. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

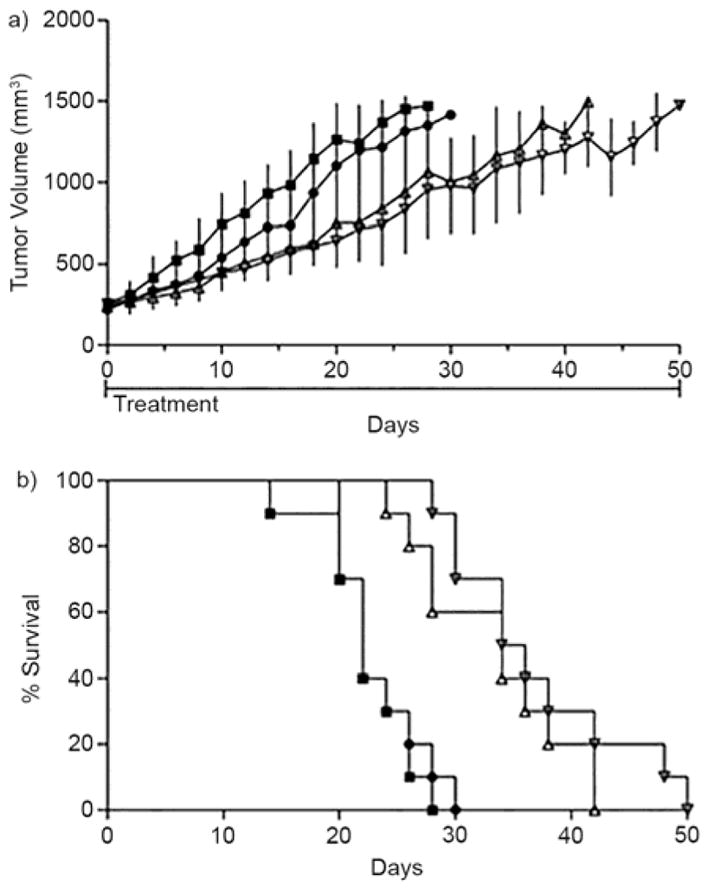

Next, we sought to provide proof-of-concept that 26 could solubilize an insoluble anticancer agent, deliver it to animals, release its cargo, and have the drug display antitumor activity. As drug we chose albendazole (ABZ) which is an antihelmitic agent that binds β-tubulin, inhibits microtubule formation, and halts cell division; ABZ is currently studied as an anticancer agent.[36] We formulated ABZ (1.5 mM) using an excess of 26 (60 mM). For the in vivo efficacy study, female anthymic NCr-nu/nu mice were given SK-OV-3 xenograft tumors and the treatment study began when the tumors reached 250–300 mm3. Animals were dosed with 26 alone, ABZ (3.2 mg/kg) once daily, or ABZ (3.2 mg/kg) twice daily over a period of 50 days. Figure 12 shows plots of tumor volume and % survival versus time (days). We conclude that treatment with 26•ABZ extends mouse survival by attenuating the growth rates of SK-OV tumors. Overall, the work provides proof-of concept for the in vivo use of 26 as a solubilizing excipient for drug delivery applications. Macrocyclic CB[n] have also been shown by Day to be good solubilizing agents for ABZ.[36–37]

Figure 12.

Plots of: a) tumor volume, and b) percent survival versus time from the in vivo efficacy studies with 26•ABZ. Female, athymic mice (n = 10) were dosed either once or twice daily with 26•ABZ (3.2 mg/kg) through the IP route. Treatment commenced when tumors were approximately 300 mm3, during the rapid tumor growth phase. Untreated (closed squares), 26 at 681 mg/kg (closed circles), 26•ABZ once daily (open upright triangle), and 26•ABZ twice daily (open upside down triangle).

Structural Changes on the Use of Acyclic CB[n] as Solubilizing Agents

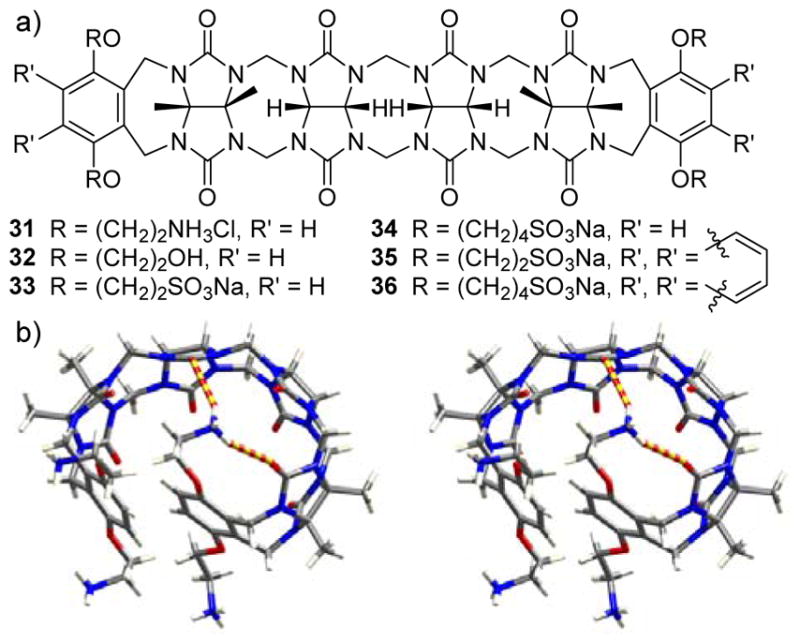

Simultaneous with the use of 26 as a solubilizing agent for in vivo delivery of ABZ, we were systematically modifying the structure of 26 to optimize it solubilisation efficiency. We first focused on the nature of the solubilizing group. Synthetically, we were able to prepare analogues of 26 where the SO3− groups were changed to NH3+ (31) or OH (32) groups (Figure 13a).[38] Compound 32 is only modestly (≈ 2 mM) water soluble which makes it inappropriate as a solubilizing excipient whereas 31 (250 mM)[39] is highly soluble in water. Unfortunately, neither 31 nor 32 functioned as a solubilizing agent for a test panel of three insoluble drugs (tamoxifen, 17α-ethynylestradiol, and indomethacin). We traced the dramatic difference in solubilizing ability back to inherent differences in the container•guest binding constants. For example, dicationic guest CHDA binds strongly to tetra-anionic host 33 (Ka = 4.6 × 106 M−1), modestly to neutral host 32 (Ka = 1.1 × 104 M−1), and quite weakly to tetra-cationic host 31 (Ka = 3.3 × 102 M−1). This decrease in observed binding constant is not simply due to changes in ion-ion interactions but also reflects the structure of the free host. Figure 13b shows the x-ray crystal structures of 31 which reveals the presence of a self folded geometry driven by +NH•••O=C ion dipole interactions in the free host.

Figure 13.

a) Chemical structures of 31 – 36, and b) cross eyed stereoview of the crystal structures of 31.

Compound 27 is our most potent binder, but it suffers from modest inherent solubility (18 mM) which limits the concentration of 27•drug that can be achieved. Accordingly, we studied the influence of (CH2)n linker length between the aromatic sidewalls and the SO3− solubilizing groups in the form of compounds 27, 35, and 36.[40] Compounds 35 (68 mM) and 36 (196 mM) possess high inherent aqueous solubility and do not undergo self-association up to 66 mM but solutions of 36 do become viscous at higher concentrations. PSDs were generated for 15 drugs with 27, 35, 36, HP-β-CD, and SBE-β-CD which allows some generalizations to be made. First, 27 is a more potent binder than 35 or 36 by 2 – 25-fold. Despite the stronger binding constants with 27, higher concentrations of drug can be achieved using container 35 because of its higher inherent solubility. All three containers bind more strongly toward the test drug panel than HP-β-CD. We also compared the solubilisation ability of 35 with that of SBE-β-CD. In this case, the comparison is more subtle with similar binding constants in many cases and substantial differences in others. The higher inherent solubility of SBE-β-CD means that higher drug concentrations are achieved with SBE-β-CD than with 35 about 50% of the time. Notably, 35 succeeds where SBE-β-CD fails (PBS-1086, camptothecin) and performs much better in others (MEPBZ).[40] This new container 35 is not toxic according to in vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo MTD assays which suggests that 35 should be further developed as an alternative to SBE-β-CD for real world formation applications.

2.4.2.3. Use of Acyclic CB[n]-type Containers as a Broad Spectrum Reversal Agent for Neuromuscular Blocking Agents

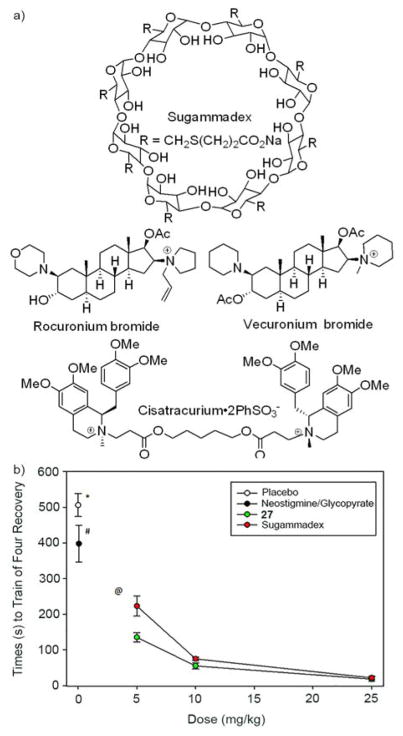

In the application of cyclodextrins and cucurbiturils as solubilizing excipients for insoluble drugs it is important that the container•drug binding constant not be so strong as to prevent drug release in vivo.[41] However, for container•drug complexes that are tight another class of applications becomes possible whereby the container is used as a reversal and/or sequestration agent. Sugammadex is an anionic γ-cyclodextrin derivative (Figure 14a) – marketed by Merck under the trade name Bridion™ – that was shown to bind tightly and selectively to the neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) rocuronium (Ka ≈ 107 M−1) and vecuronium.[42] Rocuronium and vecuronium and used by anesthesiologists to block the muscle function of patients on the surgical table, however, the residual effects of NMBAs post-surgically result in muscle weakness and difficulty breathing, which increases healthcare costs and patient mortality. Given that rocuronium and vecuronium are hydrophobic steroidal dications, that CB[n] receptors prefer dications, and that acyclic CB[n] display a special affinity toward steroids lead us to investigate whether acyclic CB[n]-type receptors might function as reversal agents for neuromuscular block in vivo. For this purpose, we first measured the binding constants of 26 and 27 toward several NMBAs and toward acetylcholine by UV/Vis competition assays (Table 2). We find that the affinity of 26 toward rocuronium (roc) and vecuronium (vec) is comparable to Sugammadex•rocuronium and importantly, that 26 discriminates against acetylcholine (ACh) which is present in the neuromuscular junction.[43] Even more impressive is the affinity of 27 toward rocuronium and vecuronium (nM range) which exceeds that of Sugammadex by approx 100-fold; 27 also binds tightly to cisatracurium (cis) which is an important clinically used NMBA. The ability of 26 and 27 to act as a broad spectrum in vivo reversal agent for NMBAs was investigated in collaboration with Prof. Matthias Eikermann.[34] Sprague Dawley rats were anesthesized with isoflurane and their muscle function was blocked with rocuronium (3.5 mg/kg) or cisatracurium (0.6 mg/kg) before the reversal agent was given. Figure 14b shows a plot of the time required to recover to a given train-of-four ratio at different doses of 27 relative to neostigmine (standard of care) which demonstrates the ability of 27 to reverse the residual neuromuscular block induced by rocuronium. Similar conclusions were reached for vecuronium and cisatracurium. Complementary assays that monitor the spontaneous breathing of the animals also indicate rapid reversal with 27. The mean arterial pressure, heart rate, and blood pH, pCO2, and pO2 were monitored upon treatment with 27 and did not show any significant differences from untreated animals.[34a] A related study investigated the use of 27 as a reversal agent for the the anesthetics ketamine and etomidate.[31] Macrocyclic CB[n] have also been investigated as reversal agents for anesthesia and neuromuscular block by Wang and Macartney.[44]

Figure 14.

a) Chemical structures of Sugammadex and NMBAs, and b) plots of the recovery of train of four ratio at different doses of reversal agents.

Table 2.

Binding constants (Ka/106 M−1) measured for the complexes between hosts Sugammadex, 26, and 27 toward rocuronium, vecuronium, cisatracurium, and ACh.

| Guest[a] | Sugammadex | 26 | 27 |

|---|---|---|---|

| rocuronium | 18 | 8.4 | 3400 |

| vecuronium | 5.7 | 5.8 | 1600 |

| cisatracurium | 0.0049 | 0.97 | 4.8 |

| ACh | – | 0.024 | 0.18 |

– = not reported.

An important issue for the further development of 27 as a broad spectrum reversal agent for NMBAs is the selectivity of 27 toward the NMBAs versus toward other drugs that might be used or needed by the patient. When another drug has both a large binding constant and high plasma concentration, it is possible for this competing drug to displace the NMBA from the 27•NMBA complex resulting in recurarization. We performed binding studies of 27 toward 27 drugs commonly used during or after surgery.[45] Then, we performed computer simulations of a simple equilibrium binding model that takes into account the binding constants of 27 toward NMBA and competing drug, the estimated binding constant of NMBA toward the biological receptor, and the plasma concentrations. Under the constraints of the simulations, we find that none of the 27 drugs studied results in significant displacement interactions.

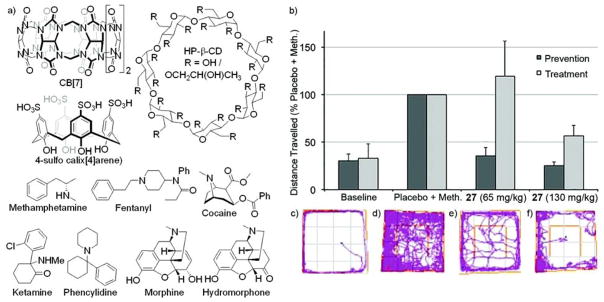

2.4.2.4. Use of Acyclic CB[n]-type Containers as a Reversal Agent for Intoxication with Methamphetamine

The recreational use of drugs is a major societal problem which results in a large number of overdoses and mortality. In the United States, it is estimated that 10.2% of the population (27 million) used an illicit drug in the past month and that the emergency room costs amount to $11 billion per year. Although naloxone is used to treat opioid overdose and addiction there are no pharmacotherapies used to treat methamphetamine or cocaine. We envisioned that 27 would bind to methamphetamine in the bloodstream and induce a negative concentration gradient from the brain and thereby modulate the hyperlocomotion induced by methamphetamine.[46] Using a combination of 1H NMR, UV/Vis, and isothermal titration calorimetry (competition) assays we measured the binding affinity of seven drugs (methamphetamine, fentanyl, cocaine, ketamine, phencyclidine, morphine, hydromorphone) toward several containers (26, 27, CB[7], HP-β-CD, and 4-sulfo calix[4]arene (SC4A)). We find that 26 and 27 display a broad affinity toward the drugs of abuse with Ka values in the 104 – 107 M−1 range whereas HP-β-CD and SC4A bound more weakly. Highest affinity was displayed by 26, 27, and CB[7] toward methamphetamine and fentanyl by virtue of their phenethyl ammonium binding epitope. We performed in vivo pre-treatment experiments and in vivo reversal experiments using Sprague-Dawley rats that were treated with methamphetamine (0.30 mg/kg) or placebo. We montiored the motion of the animals in a 100×100×40 cm open field by video recording. Figure 15b shows a plot of total distance travelled for the different treatment groups whereas panels c-f show plots of the motion of the animals. We conclude that pretreatment with 27 (65 or 130 mg/kg) effectively prevents the hyperlocomotive effect of methamphetamine. In constrast, reversal of methamphetamine is only partially effective at 130 mg/kg 27. Future studies aim to synthesize new acyclic CB[n]-type compounds that display higher affinity and selectivity toward drugs of abuse for enhanced in vivo function. Recently, Kim and co-workers reported the use of OFETs coated with CB[7] derivatives function as a portable amperometric sensor for amphetamine-type stimulants.[47]

Figure 15.

a) Chemical structures of HP-β-CD, SC4A, and selected drugs of abuse, b) bar graph showing distance traveled as a percentage of the placebo + methamphetamine activity level within 20 min; error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Tracking plots illustrate the distance traveled by one rat within 20 min in the open field; c) baseline, no methamphetamine; d) methamphetamine (0.30 mg/kg) + placebo; e) methamphetamine (0.30 mg/kg) + 27 (65 mg/kg); and f) methamphetamine (0.30 mg/kg) + 27 (130 mg/kg).

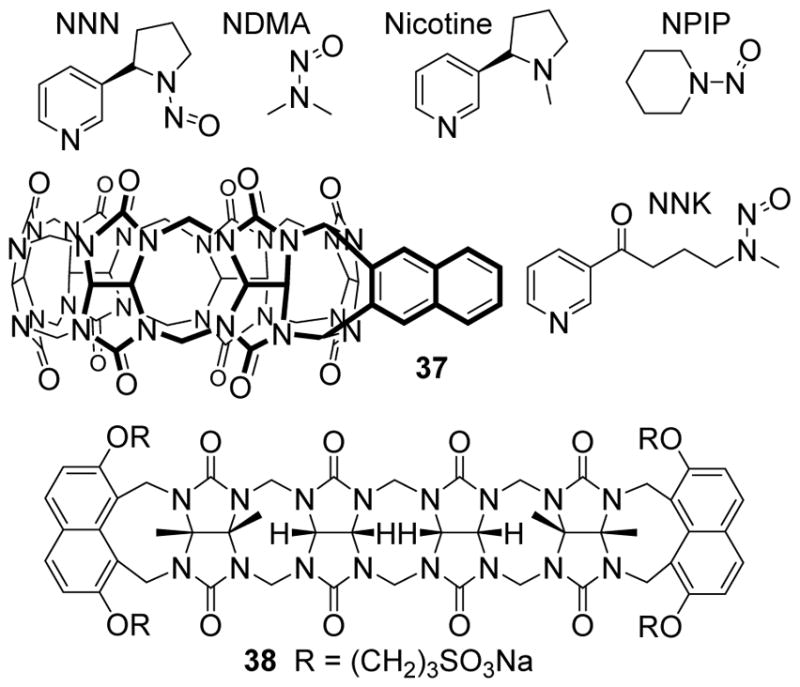

2.4.2.5. Use of Acyclic CB[n]-type Containers as Components of Sensor Arrays

The use of CB[n]•dye complexes as key components of sensor systems has been extensively studied, most notably by Nau and co-workers.[48] Advantageously, acyclic CB[n]-type receptors feature aromatic sidewalls and in collaboration with Prof. Pavel Anzenbacher we have found that the dialkoxynapthalene walls of 38 fluoresce at ≈ 370 nm when excited at 301 nm. Interestingly, the fluoresence of 38 is quenched by the non-covalent binding of metals (e.g. Eu3+, Yb3+, Zn2+, Ba2+, Hg2+) at the ureidyl C=O portals. When a guest (analyte) is added, the metal ion can be displaced and results in a change in fluorescence.[49] The fluoresence is either recovered or reset to a different level depending on the affinity of the guest and its ability to perturb the fluorescence of the host. Accordingly, a two component sensor was prepared consisting of 38 as a more flexible cross reactive component and 37 which is a more rigid and selective receptor.[49] As analytes we tested 12 compounds including the cancer associated nitrosamines NDMA, NPIP, NNN, and NNK. The response of the host-metal-analyte solutions were measured at 320 and 370 nm in a 1536-well plates. Linear discriminant analysis resulted in 100% correct classification by the leave-one-out procedure (Figure 16). The same sensor array could also be used to identify NNN and NNK concentrations even in the presence of interfering nicotine. Subsequently, this same two-component sensor array was used to correctly classify seven different over-the-counter drugs (cimetifine, ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine, doxylamine, phenylephrine, pseudoephedrine) and even OTC cold remedies.[50] Quantitative analysis of mixtures of doxylamine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylephrine was also possible as was the direct urinalysis of doxylamine after taking NyQuil. Overall, these results and related studies[51] show the great potential of strategic combinations of fluorescent cross-reactive acyclic CB[n]-type and selective macrocyclic CB[n] receptors as components of sensing arrays to create high throughput assays for biologically relevant analytes.

Figure 16.

a) Chemical structures of selected analytes, and hosts 37 and 38.

3. Summary and Outlook

In summary, we have presented our journey in the exploration of acyclic CB[n]-type receptors incorporating at least two glycoluril building blocks. Early investigations probed the diastereoselective formation of C-shaped methylene bridged glycoluril dimers which constitute a fundamental step in the mechanism of CB[n] formation. Methylene bridged glycoluril dimers capped with aromatic sidewalls undergo discrete self-association (dimerization) in water and organic solvents which lead to the investigation of multicomponent self-sorting systems. Probing the later steps of CB[n] formation lead to the isolation of glycoluril oligomers 12H – 16, nor-seco-CB[n], and acyclic decamer 17. By virtue of the polycyclic framework, pentamer 15 and hexamer 16 are preorganized and retain the key recognition properties of macrocyclic CB[n] with only an ≈100-fold penalty in binding affinity. A wide variety of acyclic CB[n] (aromatic wall variants, solubilizing group variants, linker variants) have been prepared based on glycoluril trimer and tetramer which possess outstanding recognition properties. In particular, 26 and 27 have been used as solubilizing excipients for insoluble drugs in water. Compounds 26 and 27 are not cytotoxic according to in vitro metabolic and cell death assays, are well tolerated in mice, do not inhibit the hERG ion channel, do not alter blood pH or blood gases, and pass the Ames test. Albendazole formulated with 26 was used to treat animals bearing SK-OV-3 xenografts. Containers 26 and 27 function well as in vivo reversal agents for neuromuscular block induced by rocuronium, vecuronium, and cisatracurium. Most recently, the ability of 27 to modulate the hyperlocomotive effect of methamphetamine in rats. Finally, a sensing ensemble comprising a fluorescent selective macrocyclic receptor 37 with cross-reactive fluorescent acyclic CB[n] 38 displayed remarkable ability to correctly identify between and quantify cancer associated nitrosamines and over-the-counter drugs. Acyclic CB[n] possess a confluence of properties including outstanding recognition properties, lack of in vitro or in vivo toxicity, and synthetic modularity that suggests they should be developed further for a wide range of real world chemical and biological applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Institutes of Health (CA168365) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1404911) for financial support.

Biography

Lyle Isaacs (right) was born in New York City, New York, where he attended the Bronx High School of Science. After obtaining a BS degree from the University of Chicago in 1991, he performed doctoral research with Professor Francois Diederich (MS 1992, UCLA; PhD 1995, ETH-Zürich). After an NIH postdoctoral fellowship with Professor George Whitesides at Harvard, he joined the faculty at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Maryland, College Park, in 1998 where he is currently Professor of Chemistry. Lyle was elected Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2013 for his work on the development of cucurbit[n]uril molecular containers and self-sorting systems.

Shweta Ganapati (left) was born in Odisha, India. She grew up in Delhi and attended The Mother’s International School. Thereafter, she obtained BS (2010) and MS (2012) degrees from St. Stephen’s College at the University of Delhi. She started graduate school at the University of Maryland, College Park in 2012 where she performed her doctoral research in the laboratory of Professor Lyle Isaacs and obtained her PhD degree in 2017. Shweta worked on the development of acyclic CB[n] containers as drug reversal agents for drugs of abuse and neuromuscular blocking agents.

References

- 1.a) Freeman WA, Mock WL, Shih NY. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:7367–7368. [Google Scholar]; b) Kim J, Jung IS, Kim SY, Lee E, Kang JK, Sakamoto S, Yamaguchi K, Kim K. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:540–541. [Google Scholar]; c) Day AI, Arnold AP, Blanch RJ, Snushall B. J Org Chem. 2001;66:8094–8100. doi: 10.1021/jo015897c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Day AI, Blanch RJ, Arnold AP, Lorenzo S, Lewis GR, Dance I. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:275–277. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020118)41:2<275::aid-anie275>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Liu S, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16798–16799. doi: 10.1021/ja056287n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Cheng XJ, Liang LL, Chen K, Ji NN, Xiao X, Zhang JX, Zhang YQ, Xue SF, Zhu QJ, Ni XL, Tao Z. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:7252–7255. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Li Q, Qiu SC, Zhang J, Chen K, Huang Y, Xiao X, Zhang YJ, Li F, Zhang YQ, Xue SF, Zhu QJ, Tao Z, Lindoy LF, Wei G. Org Lett. 2016;18:4020–4023. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Biedermann F, Uzunova VD, Scherman OA, Nau WM, De Simone A. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15318–15323. doi: 10.1021/ja303309e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Masson E, Ling X, Joseph R, Kyeremeh-Mensah L, Lu X. RSC Adv. 2012;2:1213–1247. [Google Scholar]; c) Isaacs L. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:2052–2062. doi: 10.1021/ar500075g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Assaf KI, Nau WM. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:394–418. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00273c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Barrow SJ, Kasera S, Rowland MJ, del Barrio J, Scherman OA. Chem Rev. 2015;115:12320–12406. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Shetty D, Khedkar JK, Park KM, Kim K. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:8747–8761. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00631g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cram DJ, Cram JM. Container Molecules and Their Guests. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z, Nalluri SKM, Stoddart JF. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:2459–2478. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00185a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Zimmerman SC. Top Curr Chem. 1993;165:71–102. [Google Scholar]; b) Rowan AE, Elemans JAAW, Nolte RJM. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:995–1006. [Google Scholar]; c) Klaerner FG, Kahlert B. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:919–932. doi: 10.1021/ar0200448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Harmata M. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:862–873. doi: 10.1021/ar030164v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Runarsson OV, Artacho J, Waernmark K. Eur J Org Chem. 2012;2012:7015–7041. [Google Scholar]; f) Klaerner FG, Schrader T. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:967–978. doi: 10.1021/ar300061c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Sijbesma RP, Nolte RJM. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6695–6696. [Google Scholar]; b) Sijbesma RP, Wijmenga SS, Nolte RJM. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9807–9813. [Google Scholar]; c) Deutman ABC, Cantekin S, Elemans JAAW, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9165–9172. doi: 10.1021/ja5032997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Witt D, Lagona J, Damkaci F, Fettinger JC, Isaacs L. Org Lett. 2000;2:755–758. doi: 10.1021/ol991382k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chakraborty A, Wu A, Witt D, Lagona J, Fettinger JC, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8297–8306. doi: 10.1021/ja025876f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wu A, Chakraborty A, Witt D, Lagona J, Damkaci F, Ofori M, Chiles K, Fettinger JC, Isaacs L. J Org Chem. 2002;67:5817–5830. doi: 10.1021/jo0258958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Stancl M, Necas M, Taraba J, Sindelar V. J Org Chem. 2008;73:4671–4675. doi: 10.1021/jo800699s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stancl M, Gargulakova Z, Sindelar V. J Org Chem. 2012;77:10945–10948. doi: 10.1021/jo302063j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaacs L, Witt D, Lagona J. Org Lett. 2001;3:3221–3224. doi: 10.1021/ol016561s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukhopadhyay P, Wu A, Isaacs L. J Org Chem. 2004;69:6157–6164. doi: 10.1021/jo049976a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Wu A, Chakraborty A, Fettinger JC, Flowers RA, II, Isaacs L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:4028–4031. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021104)41:21<4028::AID-ANIE4028>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wu A, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4831–4835. doi: 10.1021/ja028913b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ghosh S, Wu A, Fettinger JC, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. J Org Chem. 2008;73:5915–5925. doi: 10.1021/jo8009424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Liu S, Ruspic C, Mukhopadhyay P, Chakrabarti S, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15959–15967. doi: 10.1021/ja055013x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mukhopadhyay P, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14093–14102. doi: 10.1021/ja063390j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay P, Isaacs L. J Syst Chem. 2010;1:6. [Google Scholar]; d) Cao LP, Wang JG, Ding JY, Wu AX, Isaacs L. Chem Commun. 2011;47:8548–8550. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13288a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Nowak P, Otto S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9222–9239. doi: 10.1021/ja402586c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilberg L, Zhang B, Zavalij PY, Sindelar V, Isaacs L. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:4041–4050. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00184f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.She NF, Moncelet D, Gilberg L, Lu XY, Sindelar V, Briken V, Isaacs L. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:15270–15279. doi: 10.1002/chem.201601796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnett CA, Witt D, Fettinger JC, Isaacs L. J Org Chem. 2003;68:6184–6191. doi: 10.1021/jo034399w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mock WL, Shih N-Y. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4440–4446. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marquez C, Hudgins RR, Nau WM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5806–5816. doi: 10.1021/ja0319846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Huang WH, Liu S, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14744–14745. doi: 10.1021/ja064776x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang WH, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:7425–7427. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Huang WH, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Org Lett. 2008;10:2577–2580. doi: 10.1021/ol800893n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Huang WH, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8446–8454. doi: 10.1021/ja8013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Huang WH, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Org Lett. 2009;11:3918–3921. doi: 10.1021/ol901539q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Lucas D, Minami T, Iannuzzi G, Cao L, Wittenberg JB, Anzenbacher P, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17966–17976. doi: 10.1021/ja208229d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cao L, Isaacs L. Org Lett. 2012;14:3072–3075. doi: 10.1021/ol3011425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Vinciguerra B, Cao L, Cannon JR, Zavalij PY, Fenselau C, Isaacs L. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13133–13140. doi: 10.1021/ja3058502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Cao L, Hettiarachchi G, Briken V, Isaacs L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:12033–12037. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Robinson EL, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Supramol Chem. 2015:288–297. doi: 10.1080/10610278.2014.940952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Vinciguerra B, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Org Lett. 2015;17:5068–5071. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Yu Y, Li J, Zhang M, Cao L, Isaacs L. Chem Commun. 2015;51:3762–3765. doi: 10.1039/c5cc00236b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Bockus AT, Smith LC, Grice AG, Ali OA, Young CC, Mobley W, Leek A, Roberts JL, Vinciguerra B, Isaacs L, Urbach AR. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:16549–16552. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Li W, Bockus AT, Vinciguerra B, Isaacs L, Urbach AR. Chem Commun. 2016;52:8537–8540. doi: 10.1039/c6cc03193e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Webber MJ, Appel EA, Vinciguerra B, Cortinas AB, Thapa LS, Jhunjhunwala S, Isaacs L, Langer R, Anderson DG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:14189–14194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616639113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas D, Isaacs L. Org Lett. 2011;13:4112–4115. doi: 10.1021/ol201636q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Nau WM, Florea M, Assaf KI. Isr J Chem. 2011;51:559–577. [Google Scholar]; b) Biedermann F, Nau WM, Schneider HJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:11158–11171. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stancl M, Hodan M, Sindelar V. Org Lett. 2009;11:4184–4187. doi: 10.1021/ol9017886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Ma D, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. J Org Chem. 2010;75:4786–4795. doi: 10.1021/jo100760g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ma D, Hettiarachchi G, Nguyen D, Zhang B, Wittenberg JB, Zavalij PY, Briken V, Isaacs L. Nat Chem. 2012;4:503–510. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang B, Isaacs L. J Med Chem. 2014;57:9554–9563. doi: 10.1021/jm501276u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stancl M, Gilberg L, Ustrnul L, Necas M, Sindelar V. Supramol Chem. 2014;26:168–172. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stella VJ, Rajewski RA. Pharm Res. 1997;14:556–567. doi: 10.1023/a:1012136608249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okimoto K, Rajewski RA, Uekama K, Jona JA, Stella VJ. Pharm Res. 1996;13:256–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1016047215907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. [Accessed August 3, 2017];FDA-Approved Captisol-enabled Drugs. http://www.captisol.com/partnerships.

- 29.a) Walker S, Oun R, McInnes FJ, Wheate NJ. Isr J Chem. 2011;51:616–624. [Google Scholar]; b) Day AI, Collins JG. Supramol Chem Mol Nanomater. 2012;3:983–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen C, Ma D, Meany B, Isaacs L, Wang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7254–7257. doi: 10.1021/ja301462e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diaz-Gil D, Haerter F, Falcinelli S, Ganapati S, Hettiarachchi GK, Simons JCP, Zhang B, Grabitz SD, Duarte IM, Cotten JF, Eikermann-Haerter K, Deng H, Chamberlin NL, Isaacs L, Briken V, Eikermann M. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:333–345. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oun R, Floriano RS, Isaacs L, Rowan EG, Wheate NJ. Toxicol Res. 2014;3:447–455. doi: 10.1039/C4TX00082J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hettiarachchi G, Samanta SK, Falcinelli S, Zhang B, Moncelet D, Isaacs L, Briken V. Mol Pharmaceut. 2016;13:809–818. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.a) Hoffmann U, Grosse-Sundrup M, Eikermann-Haerter K, Zaremba S, Ayata C, Zhang B, Ma D, Isaacs L, Eikermann M. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:317–325. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182910213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Haerter F, Simons JCP, Foerster U, Moreno Duarte I, Diaz-Gil D, Ganapati S, Eikermann-Haerter K, Ayata C, Zhang B, Blobner M, Isaacs L, Eikermann M. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1337–1349. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uzunova VD, Cullinane C, Brix K, Nau WM, Day AI. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:2037–2042. doi: 10.1039/b925555a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Y, Buck DP, Morris DL, Pourgholami MH, Day AI, Collins JG. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:4509–4515. doi: 10.1039/b813759e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y, Pourgholami MH, Morris DL, Collins JG, Day AI. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:3328–3337. doi: 10.1039/c003732j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang B, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:2413–2422. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42603c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sigwalt D, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Supramol Chem. 2016;28:825–834. doi: 10.1080/10610278.2016.1167893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sigwalt D, Moncelet D, Falcinelli S, Mandadapu V, Zavalij PY, Day A, Briken V, Isaacs L. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:980–989. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stella VJ, Rao VM, Zannou EA, Zia V. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 1999;36:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bom A, Bradley M, Cameron K, Clark JK, Van Egmond J, Feilden H, MacLean EJ, Muir AW, Palin R, Rees DC, Zhang M-Q. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:265–270. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020118)41:2<265::aid-anie265>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma D, Zhang B, Hoffmann U, Sundrup MG, Eikermann M, Isaacs L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:11358–11362. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.a) Macartney DH. Future Med Chem. 2013;5:2075–2089. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gamal-Eldin MA, Macartney DH. Can J Chem. 2014;92:243–249. [Google Scholar]; c) Chen H, Chan JYW, Li S, Liu JJ, Wyman IW, Lee SMY, Macartney DH, Wang R. RSC Adv. 2015;5:63745–63752. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganapati S, Zavalij PY, Eikermann M, Isaacs L. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:1277–1287. doi: 10.1039/c5ob02356d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganapati S, Grabitz SD, Murkli S, Scheffenbichler F, Rudolph MI, Zavalij PY, Eikermann M, Isaacs L. Chembiochem. 2017;18:1583–1588. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201700289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jang Y, Jang M, Kim H, Lee SJ, Jin E, Koo JY, Hwang I-C, Kim Y, Ko YH, Hwang I, Oh JH, Kim K. Chem. 2017;3:641–651. [Google Scholar]

- 48.a) Dsouza R, Hennig A, Nau W. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:3444–3459. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ghale G, Nau WM. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:2150–2159. doi: 10.1021/ar500116d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minami T, Esipenko NA, Zhang B, Isaacs L, Nishiyabu R, Kubo Y, Anzenbacher P. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:20021–20024. doi: 10.1021/ja3102192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minami T, Esipenko N, Akdeniz A, Zhang B, Isaacs L, Anzenbacher P. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15238–15243. doi: 10.1021/ja407722a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.a) Minami T, Esipenko N, Zhang B, Isaacs L, Anzenbacher PJ. Chem Commun. 2014;50:61–63. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47416j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shcherbakova EG, Zhang B, Gozem S, Minami T, Zavalij PY, Pushina M, Isaacs L, Anzenbacher P. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139 doi: 10.1021/jacs.1027b06371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]