Abstract

Objective:

There is currently no conclusive scientific evidence available regarding the role of the 18F-FDG PET/CT for detecting pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer (PMCRC) in patients operated on for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM). In the follow up of patients who underwent surgery for CRLM, we compare CT-scan and 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with PMCRC.

Methods:

We designed the study prospectively performing an 18F-FDG PET/CT on all patients operated on for CRLM where the CT-scan detected PMCRC during the follow up. We included patients who were operated on for PMCRC because the histological findings were taken as a control rather than biopsies.

Results:

Of the 101 pulmonary nodules removed from 57 patients, the CT-scan identified a greater number (89 nodules) than the 18F-FDG PET/CT (75 nodules) (p < 0.001). Sensitivity was greater with the CT-scan (90 vs 76%, respectively) with a lower specificity (50 vs 75%, respectively) than with the 18F-FDG PET/CT. There were no differences between positive-predictive value and negative-predictive value. The 18F-FDG PET/CT detected more pulmonary nodules in four patients (one PMCRC in each of these patients) and more extrapulmonary disease in six patients (four mediastinal lymph nodes, one retroperitoneal lymph node and one liver metastases) that the CT-scan had not detected.

Conclusion:

Although CT-scans have a greater capacity to detect PMCRC, the 18F-FDG PET/CT could be useful in the detection of more pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease not identified by the CT-scan.

Advances in knowledge:

We tried to clarify the utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the management of this subpopulation of patients.

Introduction

Only 1–2% of the patients with pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer (PMCRC) will be candidates for lung resection.1–3 Although chemotherapy has improved survival in these patients,4 it is important to detect pulmonary metastases early on because surgery continues to be the only potentially curative treatment option with 5-year survival between 38 and 63%.5,6 A CT scan7,8 is the most accepted method for the detection of PMCRC but it is less effective for detecting extrapulmonary disease.7 The size, number, location and morphology of pulmonary nodules could be guides for identifying whether the nodules are benign or malignant and, for the diagnosis,9,10 some authors monitor the growth of the pulmonary nodules in the follow up using CT and/or a pulmonary biopsy.

Some authors11,12 have reported that the 18F-FDG PET/CT may be a useful test to detect PMCRC and extrapulmonary disease, and have also been able to report data about their malignant nature.13 However, there is little evidence about the usefulness of the 18F-FDG PET/CT compared with the CT-scan in the follow up of these patients.

The aim of this study was to analyse the benefits of preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT for detecting pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease in patients operated on for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) when the CT-scan detected PMCRC during the follow up. We compared the findings obtained by both the CT-scan and the 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients operated on for these PMCRC with the histological findings of the surgical specimen.

Methods and Materials

Patient selection

We designed this prospective and non-randomized study from January 2000 to December 2013. We performed an 18F-FDG PET/CT on all the patients operated on for CRLM when the CT-scan detected PMCRC during the follow-up. The patients that only received chemotherapy as their treatment, or for whom there were no histological data about the PMCRC, were excluded.

All the patients were informed of the objectives of the study and they signed the informed consent document. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Virgen de la Arrixaca Clinic and University Hospital. After CRLM surgery, all the patients were reviewed by oncologists and liver surgeons using tumour markers and a CT-scan in our hospital every 3 months during the first year, every 4 months during the second year, every 6 months during the third year and thereafter, once a year.

Study design

When in the follow up of our patients operated on for CRLM the CT-scan detected any PMCRC, we performed an 18F-FDG PET/CT. According to our follow-up protocol, once a nodule suspected of malignancy is found in the CT, we perform a PET/CT within a week to be able to plan the most adequate treatment. All the CT images were evaluated by the unit of thoracic radiologists consisting of two radiologists (MF, AP) and all the PET-CT scans were evaluated by the unit of nuclear radiologists comprising of two nuclear radiologists (JN, LF). Only the patients with resection of the PMCRC were included in the study because the histological findings of the surgical specimen were taken as a control. Pulmonary nodules were considered benign when the pathological study was benign or when they were false positives (not being detected during the surgery). CT-scan and 18F-FDG PET/CT findings were compared with the histological results.

CT-scan imaging protocol

CT-scans were performed following standard procedure in the follow up of these patients. Contrast-enhanced scans were obtained from the apex of the lungs to the perineum at 120 kV (peak), 140 mA and 0.3 s for a tube rotation and a 0.8 pitch. Contrast-enhanced images were performed after IV administration of 130 ml of contrast medium at a flow rate of 3 ml s−1, 30 min after the introduction of 450 ml of oral contrast. The thickness of the reconstruction was 3 mm. The exploration of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis was initiated at 45, 75 and 90 s, respectively, after the injection.

The criteria used to define pulmonary metastases was the absence of the nodule in a previous CT performed on patients operated on for CRLM. From the morphological–radiological point of view, the analysis of the pulmonary nodule includes the analysis of various aspects such as growth rate, size, contours, internal content (calcification, cavitation and fat) and vascularization.

18F-FDG PET/CT imaging protocol

Imaging acquisitions were performed using an integrated PET/CT system (Gemini GXLPET/CT, Philips®). All patients had fasted for at least 6 h and had their blood glucose levels within the normal range, prior to the intravenous injection of 370 MBq of 18F-FDG. The procedure for data acquisition was as follows: CT scanning was performed first, without using oral or intravenous contrast agents, from the base of the skull to the upper thighs, with 120 kV, 100 mA and a 5-mm section thickness. Immediately after CT scanning, a PET emission scan that covered the identical transverse field of view was obtained, with 3-min acquisition time per bed position. Image interpretation was carried out through qualitative (visual) and semi-quantitative analysis using the standardized uptake value (SUV), and the mean ± SD of maximum-pixel SUV (SUVmax) of the lesions was calculated. The 18F-FDG PET/CT was considered positive when the SUV of the FDG uptake was ≥2.5.

The findings were interpreted as pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease (mediastinal, retroperitoneal or hilar lymph nodes, repeat liver metastases, recurrence of colorectal cancer and/or peritoneal surface malignancy).

Surgical criteria

Patients with PMCRC, previously operated on by our unit for CRLM were selected for surgical treatment if they met the following criteria (established by the oncologist, liver surgeons, thoracic surgeons and radiologists): (1) no presence of colorectal cancer recurrence; (2) no presence of non-resectable extrapulmonary disease; (3) a good general status of the patients for surgical resection; (4) the possibility of complete resection of the PMCRC and in cases of simultaneous liver metastases the possibility of removing all the disease and (5) no more than three PMCRCs.

In patients with primary tumour recurrence, non-resectable hepatic or extrahepatic metastases and more than three PMCRCs, neoadjuvant chemotherapy was initiated. In these cases, pulmonary resection was performed if reduction of the disease could be achieved and it was considered resectable.

The strategy for pulmonary resection is related to the number, location and synchronism of the PMCRC with the CRLM. When the PMCRCs were synchronous, the following criteria were used: (1) when a major hepatic resection and an extensive unilateral pulmonary resection or bilateral thoracotomy was planned, a first-stage liver resection was performed followed by the pulmonary resection at 4–6 weeks; (2) when a minor liver resection was planned, simultaneous lung surgery was performed if it was minor and unilateral.

Main outcome measures

The primary end-point was to analyse the role of the 18F-FDG PET/CT to detect pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease in these patients. We analysed sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value (PPV) and negative-predictive value (NPV) in the CT-scan and the 18F-FDG PET/CT. The secondary end-point was to study the relationship between the size and detection of nodule, and the relationship between size, SUV and malignancy.

Statistical analysis

The statistical data analysis was carried out using the SPSS v. 19.0 program (Chicago, IL). The numerical variables were summarized as mean ± SD, while the qualitative variables were represented as frequencies and percentages. The non-parametric test was used for a comparative analysis of the means (Kruskal-Wallis). The χ2 test was used to contrast percentages with qualitative variables. All the results were considered statistically significant at a level of p ≤ 0.05. We analysed the following parameters: sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV; and we studied the influence of the histological size of the pulmonary nodules for detecting the nodule, while also carrying out an analysis of the receiver operating characteristic curves for trying to identify a cut-off point in nodule sizes which could provide us with an acceptable sensitivity and specificity (above 80%). Finally, we analysed the influence of each mm nodule increase on the detection capacity of both the CT-scan and the 18F-FDG PET/CT using logistic regression modelling.

RESULTS

Demographic data

During the study period, 157 liver resections were performed on 390 patients owing to CRLM. Of these, 180 patients presented with pulmonary nodules in the follow-up. 57 patients with pulmonary nodules and with a suspicion of PMCRC were operated on and were included in the study. The median age was 59 years (range: 32–85) and 37 were males (53%). 68 pulmonary resections were performed: 47 patients had one pulmonary resection, 9 patients had two pulmonary resections and 1 patient had three pulmonary resections. We performed 32 left thoracotomies (47%), 28 right thoracotomies (41%) and 8 bilateral approaches (12%).

Staging results

105 pulmonary nodules were detected by preoperative image tests (n = 98) or by surgical exploration (n = 7). Of the 98 nodules detected by imaging tests, 4 pulmonary nodules were not found during the thoracothomy, so 101 pulmonary nodules were resected (97 were histologically malignant and 4 benign). The CT-scan detected a greater number of pulmonary nodules (89 nodules) than the 18F-FDG PET/CT (75 nodules) with p < 0.001 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pulmonary nodules detected by the CT-scan and the 18F-FDGPET/CT according to their histology and size

| CT-scan | 18F-FDG PET/CT | p< | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detected (n = 89)(%) | Undetected (n = 12)(%) | Detected (n = 75) (%) |

Undetected (n = 26) (%) | ||

| Malignant PN (n = 97) | 87 (98%) | 10 (83%) | 74 (99%) | 23 (88%) | 0.001 |

| Benign PN (n = 4) | 2 (2%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (12%) | n.s.s. |

| Size ≥ 10 mm (n = 73) | 69 (78%) | 4 (33%) | 63 (84%) | 10 (38%) | n.s.s. |

| Size < 10 mm (n = 28) | 20 (22%) | 8 (67%) | 12 (16%) | 16 (62%) | 0.001 |

18F-FDG PET/CT,positron emission tomography combined with CT; n.s.s., not statistically significant; PN, pulmonary nodule.

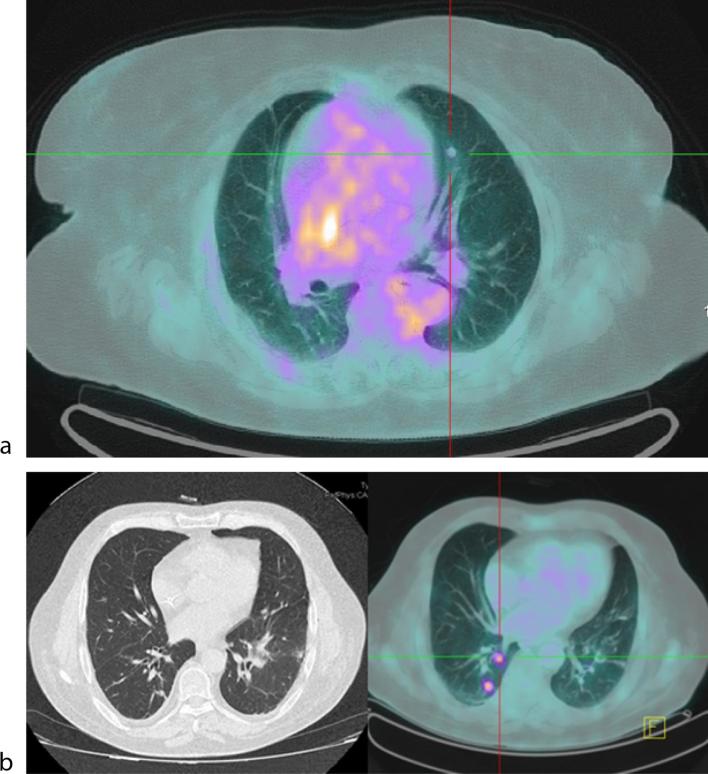

Of the malignant pulmonary nodules (n = 97), 91 of them were detected by the CT-scan and/or the 18F-FDG PET/CT (both were in agreement in the detection of 72% of these). The remaining six malignant pulmonary nodules were not detected by either the CT-scan or the 18F-FDG PET/CT. 4 nodules (4%) were detected by the 18F-FDG PET/CT that the CT-scan did not detect (Figure 1a) and 17 nodules (17%) were detected by the CT-scan that the 18F-FDG PET/CT did not detect (Figure 1b). A higher sensitivity was shown by the CT-scan (90 vs 76%, respectively) and a lower specificity (50 vs 75%, respectively) than the 18F-FDG PET/CT (Table 2). There were no differences between the two types of imaging in terms of PPV and NPV (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Malignant pulmonary nodule in the parahilar region with positive standard uptake value by 18F-FDG PET/CT (a). Malignant pulmonary nodule detected by CT-scan without positive standard uptake value by 18F-FDG PET/CT (b).

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value and negative-predictive value for the CT-scan and the 18F-FDGPET/CT

| T-scan | 18F-FDG PET/CT | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 90% [95% CI (84–96%)] | 76% [95% CI (68–85%)] |

| Specificity | 50% [95% CI (1–99%)] | 75% [95% CI (33–117%)] |

| Predictive-positive value | 98% [95% CI (95–101%)] | 99% [95% CI (96–101%)] |

| Predictive-negative value | 17% [95% CI (4–38%)] | 12% [95% CI (1–24%)] |

18F-FDG PET/CT, positron emission tomography combined with CT, CI, confidence interval.

19 patients (33%) had extrapulmonary disease. 14 thoracic lymph nodes were detected (four were only detected by CT, four only by 18F-FDG PET/CT and six using both techniques); together with 1 retroperitoneal lymph nodes (one by CT and another by 18F-FDG PET/CT) and 3 liver metastases (1 by CT, 1 by 18F-FDG PET/CT and 1 using both tests). Therefore, 18F-FDG PET/CT detected extrapulmonary disease in six patients (10%) that the CT had not detected.

Relationship between the size and detection of pulmonary nodules

For pulmonary nodules ≥ 10 mm, the diagnostic accuracy of the CT-scan and the 18F-FDG PET/CT was similar, but for pulmonary nodules < 10 mm the CT-scan had a greater diagnostic accuracy than the 18F-FDG PET/CT with a statistical significance (p < 0.001) (Table 1). In the 87 malignant pulmonary nodules detected by the CT-scan, the median size was 13 mm (range: 2–70 mm) and in the 12 undetected cases it was 5 mm (range: 3–15 mm), while in the 74 malignant pulmonary nodules detected by the 18F-FDG PET/CT, the median size was 14 mm (range: 4–70) and in the 23 undetected cases it was 7 mm (range: 2–15). Regarding the location in the lung of the malignant pulmonary nodules detected by the 18F-FDG PET/CT, we found 14 in the upper zone, 34 in the mid zone and 26 in the lower zone.

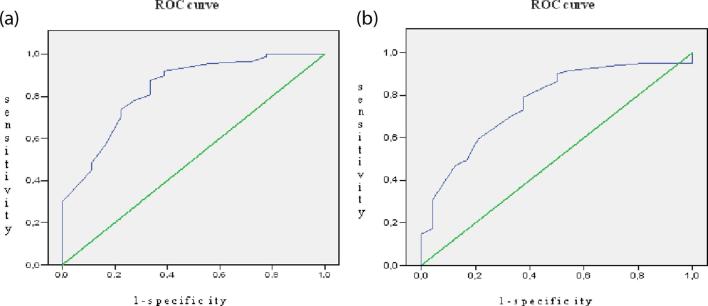

In the ROC curve analyses, the borderline size for detecting pulmonary nodules using the CT-scan was between 9 and 10 mm given a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 75% (Figure 2a), and for the 18F-FDG PET/CT, it was also between 9 and 10 mm with a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65% (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Area below the ROC curve for detecting the pulmonary nodule according to its size. ROC curve of the CT-scan (a). ROC curve of the 18F-FDG PET/CT (b). 18F-FDG PET/CT, positron emission tomography combined withCT; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

For the CT-scan, the probability of a correct diagnosis for each mm of increase in size of the pulmonary nodules is multiplied by 1.308 (OR) [95% CI (1.147–1.492)], and for the 18F-FDG PET/CT it is multiplied by 1.170 (OR) [95% CI (1.068–1.282)]. 52 (96%) of the 55 pulmonary nodules with a SUV ≥2.5 had a size ≥10 mm and 3 of them (4%)<10 mm. However, 11 (55%) of the 20 pulmonary nodules with a SUV <2.5 had a size ≥10 mm and 9 of them (45%) were <10 mm.

DISCUSSION

The presence of PMCRC detected in patients operated on for CRLM does not contraindicate surgical resection owing to the prolonged survival achieved. However, some conditions are necessary to prevent unnecessary surgery.14–16 After resection of CRLM, during the follow up, it is necessary to perform several explorations to detect the recurrence of the disease. To detect the pulmonary recurrence, the role of staging in the CT-scan has been established by several publications,17,18 owing to an increase in the possibilities of detecting PMCRC. However, the CT-scan has difficulties in distinguishing between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules, so the authors place importance on nodule size, morphology, biopsy of the nodule and progressive tumour growth.19 This means that the CT-scan could over- and understage the disease, leading to unnecessary or incomplete surgery. In this series, the CT-scan did not detect 12 pulmonary nodules (17.1%), of which 10 were malignant; and of the 89 detected, 2 were benign. In addition, the 90% sensitivity obtained by the CT-scan in our series coincides with levels reported in the literature but our specificity (50%) was lower than the level published in other series.20,21 We believe that the present results with lower specificity are mainly owing to the fact we have used pathological anatomy to describe the nature of the lesion, whereas other authors use different control methods such as resizing, radiological features or a biopsy to characterize the suspicious lesion as benign or malignant. In our experience, we indicate the resection of pulmonary nodules whenever malignancy is suspected following the criteria expressed in the section of our surgical criteria.

18F-FDG PET/CT has been used for the staging of patients with colorectal cancer for ruling out the presence of tumour dissemination22 and some authors have demonstrated its utility for identifying pulmonary nodules with a size of more than 1 cm.23,24 In the present study, 18F-FDG PET/CT was considered positive when the SUV of the FDG uptake was ≥2.5 but it is known that SUVmax values are affected by many factors (uptake time, blood glucose level etc.). The SUV is a semi-quantitative measurement of radiopharmaceutical uptake at a point of interest. Some authors described that malignant neoplasms have an SUV ≥2.5, the SUV cut-off of 2.5 is problematic and often nodules with lower values turn up to be malignant. It is for this reason that comparison with the mediastinal SUV is used in many centres and quoted in the literature. In this sense, Kim et al25 conclude that visual inspection appears sufficient for the characterization of a single pulmonary nodule and that no additional information is provided by performing semi-quantitative analysis with or without mass correction.

Few studies have analysed the role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the detection of PMCRC in patients with previously resected CRLM. Selzner et al20 analysed 76 patients with CRLM and PMCRC confirmed by percutaneous biopsy. The results of the 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with CRLM before being subjected to liver resection were compared with the CT-scan. All PMCRC were detected by the 18F-FDG PET/CT (sensitivity: 100%) and the CT-scan only identified 14 cases (sensitivity: 72%). However, in the present series, the CT-scan had a greater capacity to detect the pulmonary nodules with a sensitivity of 90% compared with that of the 18F-FDG PET/CT which was 76% (p < 0.001). We designed this study prospectively, with a higher sample size and a correlation with the histological study based on the surgical specimen instead of a pulmonary biopsy.

In this series, four pulmonary metastases that had not been detected by the CT-scan were detected by the 18F-FDG PET/CT. However, the 18F-FDG PET/CT had a 24% error rate in detecting PMCRC (23 pulmonary nodules out of the 97 malignant ones) compared with the CT-scan which did not detect 10% (10 pulmonary nodules of the malignant ones). The non-detection of PMCRC by the 18F-FDG PET/CT has been principally related, in the absence of receiving prior chemotherapy,26 with the size of the PMCRC being lower than 1 cm. Nodule size has been considered as the most influential variable in the imaging detection of pulmonary nodules. While the 18F-FDG PET/CT has difficulty detecting lesions of less than 1 cm, the CT-scan identifies lesions of less than 5 mm. Several studies27 have reported that when the mean size of the nodule is equal or greater than 9 mm, the diagnostic certainty of the 18F-FDG PET/CT is comparable with the CT-scan in the diagnosis of PMCRC. In the present series, seven of the pulmonary nodules resected were not detected by either of the image tests because they had a mean size of 5 mm. Therefore, when the nodules have a size of between 5 and 9 mm, we will be guided by the CT-scan, because in this range of nodule size, PET/CT may have false negative results in lesions without high FDG avidity, because the diameter of such nodules is close to or even below the system's resolution.

CT-scan could understage the presence of extrapulmonary disease in patients with PMCRC (recurrence of the primary tumour, the presence of new liver metastases, mediastinal lymph nodes etc.).28 Some authors29 have shown that 18F-FDG PET/CT could have a greater capacity to detect extrapulmonary disease than the CT-scan. However, Orlacchio et al30 published that the 18F-FDG PET/CT has a limited value in the detection of retroperitoneal, thoracic and hilar lymph nodes, but has greater sensitivity and specificity in the detection of liver disease compared with the CT-scan. Vigano et al described for 28.8% (17/59) of the patients, the diagnosis of extrahepatic disease was obtained thanks to PET-CT (39.5% considering non-pulmonary lesions). PET-CT modified treatment strategy in 16 (14.9 %) patients, excluding from surgery 15 (20.3 %) of 74 patients resectable at CT/MRI.31 In the present study, the 18F-FDG PET/CT detected potentially resectable extrapulmonary disease in six patients that the CT-scan had not detected, achieving R0 resection in these patients.

To conclude, the CT-scan had a greater capacity to detect PMCRC in patients with liver resection for CRLM, mainly when the nodules had a size <1 cm. 18F-FDG PET/CT could be useful in the detection of more PMCRC and extrapulmonary disease not identified by the CT-scan and this may modify the management of these patients in some cases.

Contributor Information

Victor Lopez-Lopez, Email: victorrelopez@gmail.com.

Ricardo Robles, Email: rirocam@um.es.

Roberto Brusadin, Email: robertobrusadin@gmail.com.

Asuncion López Conesa, Email: alconesa2@gmail.com.

Juan Torres, Email: tljimena@hotmail.com.

Domingo Perez Flores, Email: pedro_jgv@hotmail.com.

Jose Luis Navarro, Email: jlnf@ono.com.

Pedro Jose Gil, Email: dperez@um.es.

Pascual Parrilla, Email: pascual.parrilla2@carm.es.

REFERENCES

- 1.Byam J, Reuter NP, Woodall CE, Scoggins CR, McMasters KM, Martin RC. Should hepatic metastatic colorectal cancer patients with extrahepatic disease undergo liver resection/ablation? Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16: 3064–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yedibela S, Klein P, Feuchter K, Hoffmann M, Meyer T, Papadopoulos T, et al. Surgical management of pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer in 153 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13: 1538–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Angelica M, Kornprat P, Gonen M, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, et al. Effect on outcome of recurrence patterns after hepatectomy for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 1096–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfannschmidt J, Dienemann H, Hoffmann H. Surgical resection of pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published series. Ann Thorac Surg 2007; 84: 324–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marín C, Robles R, López Conesa A, Torres J, Flores DP, Parrilla P. Outcome of strict patient selection for surgical treatment of hepatic and pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2013; 56: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pomerri F, Pucciarelli S, Maretto I, Perrone E, Pintacuda G, Lonardi S, et al. Significance of pulmonary nodules in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 1680–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christoffersen MW, Bulut O, Jess P. The diagnostic value of indeterminate lung lesions on staging chest computed tomographies in patients with colorectal cancer. Dan Med Bull 2010; 57: A4093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanemitsu Y, Kato T, Hirai T, Yasui K. Preoperative probability model for predicting overall survival after resection of pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2004; 91: 112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anthony T, Simmang C, Hyman N, Buie D, Kim D, Cataldo P, et al. Practice parameters for the surveillance and follow-up of patients with colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 807–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassler S, Hubele F, Constantinesco A, Goetz C. Comparing respiratory gated with delayed scans in the detection of colorectal carcinoma hepatic and pulmonary metastases with 18F-FDG PET-CT. Clin Nucl Med 2014; 39: e7–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huebner RH, Park KC, Shepherd JE, Schwimmer J, Czernin J, Phelps ME, et al. A meta-analysis of the literature for whole-body FDG PET detection of recurrent colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med 2000; 41: 1177–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delbeke D, Coleman RE, Guiberteau MJ, Brown ML, Royal HD, Siegel BA, et al. Procedure guideline for tumor imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT 1.0. J Nucl Med 2006; 47: 885–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung EJ, Kim SR, Ryu CG, Paik JH, Yi JG, Hwang DY. Indeterminate pulmonary nodules in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 2967–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goèré D, Gaujoux S, Deschamp F, Dumont F, Souadka A, Dromain C, et al. Patients operated on for initially unresectable colorectal liver metastases with missing metastases experience a favorable long-term outcome. Ann Surg 2011; 254: 114–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaujoux S, Goéré D, Dumont F, Souadka A, Dromain C, Ducreux M, et al. Complete radiological response of colorectal liver metastases after chemotherapy: what can we expect? Dig Surg 2011; 28: 114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mise Y, Imamura H, Hashimoto T, Seyama Y, Aoki T, Hasegawa K, et al. Cohort study of the survival benefit of resection for recurrent hepatic and/or pulmonary metastases after primary hepatectomy for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg 2010; 251: 902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson AB 3rd, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, Chen YJ, Choti MA, Cooper HS, et al. Rectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012; 10: 1528–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin MS, Drucker EA, McLoud TC, Shepard JA. Small pulmonary nodules: detection at chest CT and outcome. Radiology 2003; 226: 489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLoud TC, Boiselle PM. Pulmonary Neoplasms : Pulmonary Neoplasms Thoracic Radiology. 2nd edn San Diego: Elsevier Inc; 2010. 253–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selzner M, Hany TF, Wildbrett P, McCormack L, Kadry Z, Clavien PA. Does the novel PET/CT imaging modality impact on the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer of the liver? Ann Surg 2004; 240: 1027–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jess P, Seiersen M, Ovesen H, Sandstrøm H, Maltbæk N, Buhl AA, et al. Has PET/CT a role in the characterization of indeterminate lung lesions on staging CT in colorectal cancer? A prospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014; 40: 719–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacks A, Peller PJ, Surasi DS, Chatburn L, Mercier G, Subramaniam RM. Value of PET/CT in the management of liver metastases, part 1. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197: W256–W259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson AJ, Lolohea S, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA. The role of positron emission tomography in the management of recurrent colorectal cancer: a review. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 102–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu X, Song X, Zhu L, Chen W, Dai D, Li X, et al. Role of (18)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Newly Found Suspected Malignant Solitary Pulmonary Lesions in Patients Who Have Received Curative Treatment for Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2017; 2017: 3458739–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SK, Allen-Auerbach M, Goldin J, Fueger BJ, Dahlbom M, Brown M, et al. Accuracy of PET/CT in characterization of solitary pulmonary lesions. J Nucl Med 2007; 48: 214–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Kessel CS, Buckens CF, van den Bosch MA, van Leeuwen MS, van Hillegersberg R, Verkooijen HM. Preoperative imaging of colorectal liver metastases after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 2805–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erdi YE, Nehmeh SA, Pan T, Pevsner A, Rosenzweig KE, Mageras G, et al. The CT motion quantitation of lung lesions and its impact on PET-measured SUVs. J Nucl Med 2004; 45: 1287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rau C, Blanc B, Ronot M, Dokmak S, Aussilhou B, Faivre S, et al. Neither preoperative computed tomography nor intra-operative examination can predict metastatic lymph node in the hepatic pedicle in patients with colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchiyama S, Haruyama Y, Asada T, Hotokezaka M, Nagamachi S, Chijiiwa K. Role of the standardized uptake value of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography in detecting the primary tumor and lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancers. Surg Today 2012; 42: 956–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orlacchio A, Schillaci O, Fusco N, Broccoli P, Maurici M, Yamgoue M, et al. Role of PET/CT in the detection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Radiol Med 2009; 114: 571–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viganò L, Lopci E, Costa G, Rodari M, Poretti D, Pedicini V, et al. Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography for Patients with Recurrent Colorectal Liver Metastases: Impact on Restaging and Treatment Planning. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]