Abstract

Early exposure to two languages is widely thought to guarantee successful bilingual development. Contradicting that belief, children in bilingual immigrant families who grow up hearing a heritage language and a majority language from birth often reach school age with low levels of skill in both languages. This outcome cannot be explained fully by influences of socioeconomic status. In this article, I summarize research that helps explain the trajectories of observed dual language growth among children in immigrant families in terms of the amount and quality of their language exposure as well as their own language use.

Keywords: bilingual development, immigrant families

As a result of worldwide immigration patterns, a large and increasing number of children grow up exposed to two languages, the majority language of the country in which they live and their family’s heritage language, which is typically a minority language in their new country. Recent research in the United States and Europe has begun to describe and explain the trajectories of language growth that characterize these children (1, 2). The findings reveal that early exposure to two languages does not guarantee native-like proficiency in two languages.

In this review, I focus on children in immigrant families who are exposed to two languages from birth. Different terms with slightly different meanings have been used to refer to these children, including simultaneous bilinguals, bilingual first-language learners, and dual language learners (DLLs).1 I begin by describing the early growth of dual language proficiency in these children and explaining the challenge this poses to some psychological theories and nonprofessional assumptions regarding bilingual development. Then I review evidence that begins to explain why bilingual trajectories look the way they do, pointing to the quantity and quality of children’s input and to children’s own language use as factors that create differences between bilingual and monolingual children’s language skills, and produce individual differences in language skill among bilingual children. I also consider the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Descriptive Facts And Explanatory Challenges

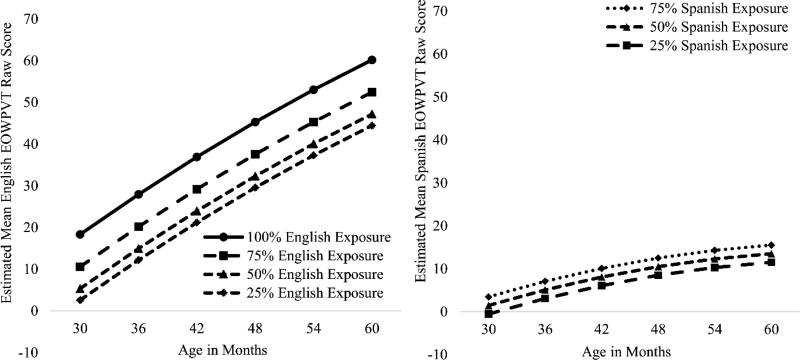

A substantial literature documents that children from immigrant families often reach school age relatively unskilled in the majority language (3, 4), while not necessarily showing strong skills in the heritage language (5). To illustrate, Figure 1 presents trajectories of growth in English and Spanish expressive vocabulary from 30 to 60 months for children from monolingual homes in which English alone is spoken and for children from bilingual homes in which Spanish and English are spoken (with the English proportion of their language exposure ranging from 90% to 10%). Estimated English growth curves for the 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% levels of exposure to English are plotted in the left panel; estimated Spanish growth curves for the 25%, 50%, and 75% levels of exposure to Spanish are plotted in the right panel (6). This figure shows that the bilingual children—those with less than 100% English input—have lower levels of English skill than the monolingual children while also having stronger skills in English than Spanish. Other studies have identified similar differences between monolingual and bilingual children, and between English and Spanish for measures of productive vocabulary and grammar (7). These descriptive facts challenge theories of human language capacity in which children simultaneously acquire two languages as quickly and successfully as one. Similarly, these facts challenge the related belief, held in and out of scientific circles, that children are linguistic sponges who quickly absorb the language or languages they hear and as a result, become proficient speakers.

Figure 1.

Estimated trajectories of English and Spanish expressive vocabulary growth from 30 to 60 months at different levels of exposure to English, controlling for parent education (N = 151 for English, 112 for Spanish).

Immigrant status is often confounded with socioeconomic status (SES), and SES contributes to widely observed differences in the United States and Europe between monolingual children from native families and bilingual children from immigrant families (5, 8). But SES is not the whole story for immigrant children, and SES explains neither the differences in vocabulary in Figure 1 nor all the differences in vocabulary and grammar in younger children (7). In the models of language growth in Figure 1, the effects of parents’ education were controlled statistically (6). In another study of children from 22 to 30 months, which found differences in vocabulary and grammar between monolingual and bilingual children, groups did not differ in level of parents’ education (7).2 Strong evidence suggests that the monolingual-bilingual gap in English and the more successful acquisition of English than Spanish reflect the nature of these children’s language experience. Here, I focus on three aspects of language experience that influence the bilingual development of children in immigrant families: the quantity of input, the quality of input, and children’s use of language.

Effects of Quantity of Input on Bilingual Development

One of the most robust findings in research on early bilingual development is a relation between the quantity of children’s exposure to each language and their levels of language development in each language. In one study, researchers estimated the number of words per hour addressed to Spanish-English bilingual children in each language from recordings via small microphones the children wore. Quantity of language exposure accounted for 50% of the variance in the children’s Spanish expressive vocabulary scores and 28% of the variance in the children’s English expressive vocabulary scores (9).

Many studies have assessed quantity of exposure to each language using estimates by parents of relative quantity. While this measure is second best, it is moderately to strongly correlated with word counts based on recordings (9) and strongly related to concurrently obtained diary records of time exposed to English and Spanish (7). Most importantly, in many studies, caregivers’ estimates of children’s relative quantity of exposure to each language significantly predict bilingual children’s skill levels in each language (10–13). Relative exposure accounts for approximately 35% of the variance in vocabulary and grammatical skills (7). Variations in the quantity of input make a difference throughout the range of variation. Children who hear only 20% of their input in one of their languages have measurable vocabularies in that language at 22 months (7), and children who hear 80% of their input in a language have smaller vocabularies than children who hear 100% of their input in a single language (14).

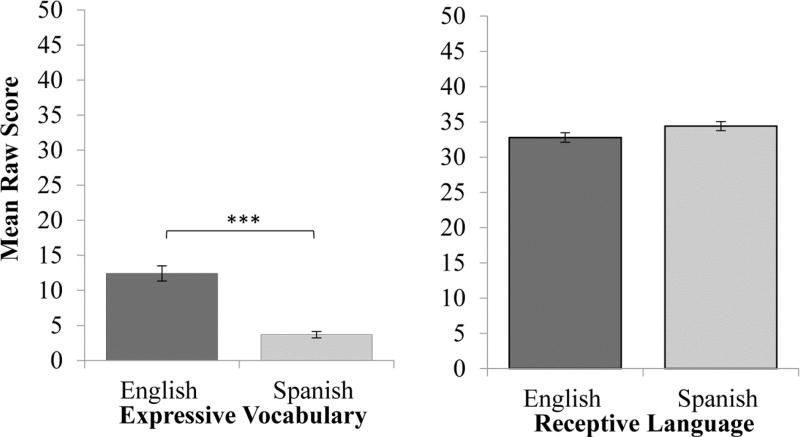

The effects of exposure might also explain other characteristics of bilingual children’s language skills. Bilingual children do not lag equally in all domains; at age 4, bilingual children are closer to the levels of monolingual children in grammar and phonology, but farthest in vocabulary (15). As illustrated in Figure 2, bilingual children often also have relatively stronger receptive than expressive skills in at least one of their languages (15–17). This might be because of bilingual children’s diminished exposure to each language; input might more frequently and reliably illustrate the phonemes and grammatical structures of a language than it provides instances of individual words, or learning words might require more exposure than learning phonemes or grammatical structures. More exposure may also be required to develop expressive than receptive skills (13, 18).

Figure 2.

Expressive vocabulary and language comprehension scores in English and Spanish for bilingual 30-month-olds (N = 115). Note: *** p < .001, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Error bars represent 1 SE of the mean.

In summary, the evidence is strong that language growth is influenced by the quantity of language input. Because bilingual children’s input is divided between two languages, they must, on average, receive less input in each than children who receive all their input in just one language, and as a result, they develop each language at a slower pace; furthermore, the effect may be greater in some domains of language than others. Recent research on bilingual development tells us that it is normal for children who are acquiring two languages at the same time to lag behind monolingual children. These lags do not mean that children are confused by their dual language exposure. In fact, measures of bilingual children’s total language growth, calculated by adding vocabulary scores across two languages, are typically equal to or greater than measures of monolingual children’s growth in their language (7, 19–21).

There are counterarguments in the literature. It has been argued that given the wide variation in how much parents talk to their children, a bilingual child may not have less exposure to one language than a monolingual child (22). It has also been argued that bilingual children experience no delay in single language development (20, 23). Consistent with the first argument, a bilingual child in a rich language environment might hear one language more than a monolingual child in a poor language environment. However, on average, the amount of exposure must differ between single-language and dual-language environments. Consistent with the second argument, some bilingual children are indistinguishable from monolingual children in their language skill—particularly in their dominant language (e.g., 13), and not every study finds a statistically significant lag or gap between the skill levels of monolingual and bilingual children (20, 24).

Many factors influence whether a study finds differences in language skill between bilingual and monolingual children, including the age of the children, the language domain assessed, whether the bilingual children are assessed in their dominant language, whether the comparison is to monolingual norms or to a group of monolingual children matched for SES, and the statistical power of the research design. At a young age, when children have small vocabularies, a gap in vocabulary size between monolingual and bilingual children may not be apparent (24). On some measures, where growth plateaus, bilingual children may catch up and close the gap quickly. For example, in one study (7), at 22 months, significantly fewer bilingual children combined words in English (on average, their dominant language) than did monolingual children, but by 25 months, most of the bilingual children had begun to combine words and the two groups no longer differed significantly. On other measures of grammar, bilingual children have caught up by age 10 (10). In contrast, for some aspects of complex morphology, for vocabulary, and in speed of lexical access, differences between bilinguals and monolinguals may persist through adulthood (2, 25, 26).

Bilingual children may score within the norms for monolingual children in their dominant language (3, 7) while still scoring lower than a matched group of monolingual children. For example, in a study of 4-year-old Spanish-English bilingual and English monolingual children from mid- to high-SES families, bilingual children’s average score was at the 45th percentile on a test of English vocabulary, which could be construed as similar to scores for monolingual children. However, these bilingual children still differed from monolingual children in the study matched for age and SES, who scored in the 85th percentile based on the same test norms (19).

Finally, statistical power influences whether differences between monolingual and bilingual children are statistically significant. In the early years of research on bilingual development, samples were small, and some claims that bilingualism causes no delay in language development were based on null results from underpowered studies (20, 23).

Effects of Quality of Input on Bilingual Development

In two studies of children from immigrant families in South Florida (27, 28), mothers kept diaries of their children’s exposure to language, logging for each half hour of the day what language the children heard and from whom. Most of the children’s exposure to English came from nonnative speakers and the proportion of input from nonnative speakers was a significant, unique negative predictor of the children’s skills in English. The effect of access to native-language input may also be reflected in the trajectories in Figure 1. The analyses that yielded these figures found a quadratic relation between the amount of children’s exposure to English and the size of their English vocabulary: Increments at the higher end of the range of English exposure conferred greater benefit than increments at the lower end. This relation may be because the amount of exposure to English was associated with the probability that one parent was a native speaker of English. Thus, in this sample, hearing more English was related to hearing more native English. In contrast, the effect of increments in exposure to Spanish language on Spanish vocabulary was linear, consistent with the finding from the diary studies that virtually all children’s input in Spanish came from native Spanish speakers.

Other research also supports the greater value of input by native speakers. In one study of immigrants to English-speaking Canada, exposure to native speakers benefitted children’s English language growth while their parents’ use of English at home did not (29). In many immigrant groups, differences in proficiency in the majority language among immigrant parents predict their children’s language growth and proficiency in adulthood (30–32). The reasons for these benefits of native input and more proficient nonnative input need to be explored fully, but studies of the child-directed speech of native and nonnative English speakers tell us that native speakers use a richer vocabulary and more complex syntax than nonnative speakers in talking to 2-year-olds (33, 34). They also tell us that nonnative speakers who rate themselves as proficient speakers differ from nonnative speakers who describe their proficiency as limited (34).

Effects of Children’s Output on Bilingual Development

In studies of bilingual children, measures of language use—or measures that include the children’s own language use—predict children’s skill level in expressive language more successfully than measures of input alone (31, 35, 36). These findings may be particularly relevant for acquiring heritage languages because bilingual children in immigrant households sometimes avoid using the family’s heritage language in favor of the majority language (37, 38). A common pattern in Spanish-English bilingual homes in the United States is for parents to address their children in Spanish and children to respond in English. Two studies suggest that this pattern of language use contributes to the skill profile depicted in Figure 2, in which bilingual children have equivalent levels of receptive skill in English and Spanish, but significantly stronger expressive skills in English (17, 39). In these studies, mothers reported on their children’s language switching in conversation. Children who favored English over Spanish in responding were compared to children who favored Spanish over English, a less frequent choice. The English responders had stronger expressive skills in English concurrently (17), and they also subsequently developed expressive vocabulary in English more rapidly (39). Language use did not affect receptive language skills uniquely (39). Thus, in addition to the effects of exposure, choosing to use English more than Spanish may explain why receptive skills in Spanish are often stronger than expressive skills among children and adults from Spanish-speaking homes (15, 26).

Summary and Conclusion

Bilingual children from immigrant families often lag monolingual children in the development of the majority language while also having poor skills in their heritage language, even when SES is controlled. This may reflect, in part, internal limits to how rapidly children can learn two languages simultaneously, but the circumstances in which children are exposed to two languages in the immigrant context are far from a perfect test of that internal capacity. Monolingual children with native parents and bilingual children in immigrant families differ in ways besides the number of languages they hear. In bilingual environments, children hear less of each language, and the quality of their exposure to the majority language is often less because their sources of that language may have limited proficiency. In addition, bilingual children in bilingual environments can choose the language they speak, and when one language is more prestigious than the other, they choose the more prestigious language.

None of these findings should be surprising. Rather, they repeat conclusions from studies of monolingual development that language acquisition depends on the quantity and quality of language experience and the opportunity to participate in conversation (40–44). The findings raise the question of whether simultaneous bilingual development is more successful in other circumstances. While differences in the quantity of input in a single language experienced by bilingual and monolingual children must always exist unless the monolingual children are deprived, differences in the quality of input and asymmetric choices in language use might not. The data at this point are unclear. In a study from Belgium, not all children exposed to Dutch and French from infancy functioned as bilinguals when they were 11 years old (37). In contrast, there are suggestions in the literature research suggests that French-English bilingualism is achieved more successfully in Canada than is Spanish-English bilingualism in the United States, and that the equal prestige of the two languages in Canada plays a role (45). In Canada, children may also have greater access to highly proficient speakers of both languages because both languages are national languages. Additional evidence that successful bilingualism is possible can be found in the success stories of families that have raised bilingual children (46), although such stories are not from a random sample of children and parents sometimes go to extraordinary lengths to arrange an environment for their children that supports their bilingual development.

One clear implication of studies of bilingual children is that we should not expect these children to be two monolinguals in one, as Grosjean (47) famously argued for adult bilinguals. The bilingual child, like the bilingual adult, will develop competencies in each language “to the extent required by his or her needs and those of the environment” (47, p. 6). The findings I have discussed suggest that bilingual children’s competencies, in addition to reflecting their communicative needs, also reflect the quantity and quality of their exposure to each language.

Evidence of the factors that impede optimal bilingual development in children from immigrant families can inform efforts to support successful bilingual outcomes in these children. Such support is important: Children from immigrant families need strong skills in the majority language to succeed in school (48, 49), and they need skills in the heritage language to communicate well with their parents and grandparents (50). Furthermore, bilingualism is an asset for interpersonal, occupational, and cognitive reasons (25). Children who hear two languages from birth can become bilingual, even if that outcome is not guaranteed. The findings I have discussed suggest that bilingual development is supported when children are exposed to both languages in ways that do not diminish the amount of exposure to each more than is necessary. In addition, to support bilingual development fully, children’s exposure to each language should come from highly proficient speakers, children’s heritage languages should be valued by society, and children should be given opportunities that encourage them to use both languages.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant HD068421 to Erika Hoff.

Footnotes

DLLs can also be children whose exposure to a second language begins later in childhood than their exposure to their first language.

This is possible in studying Spanish-English bilingual children from immigrant homes in South Florida where Spanish-speaking immigrants are often highly educated and affluent.

References

- 1.Hoff E. Language development in bilingual children. In: Bavin E, Naigles L, editors. The Cambridge handbook of child language. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2015. pp. 483–503. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unsworth S. Quantity and quality of language input in bilingual language development. In: Nicoladis E, Montanari S, editors. Lifespan perspectives on bilingualism. Berlin, Germany: de Gruyter; 2016. pp. 136–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammer CS, Hoff E, Uchikoshi Y, Gillanders C, Castro DC, Sandilos LE. The language and literacy development of young dual language learners: A critical review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2014;29:715–733. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCabe A, Tamis-LeMonda C, Bornstein MH, Cates CB, Golinkoff R, Hirsh-Pasek K, Wishard Guerra A. Multilingual children: Beyond myths and towards best practices. [Retrieved October 1, 2017];SRCD Social Policy Report, 27, No. 4. 2013 from https://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/documents/washington/spr_brief_2014_04_09_multilingualchildren.pdf.

- 5.Scheele AF, Leseman PP, Mayo AY. The home language environment of monolingual and bilingual children and their language proficiency. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2010;31:117–140. doi: 10.1017/S0142716409990191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoff E, Ribot KM. Language growth in English monolingual and Spanish-English bilingual children from 2.5 to 5 years. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.071. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Hoff E, Core C, Place S, Rumiche R, Señor M, Parra M. Dual language exposure and early bilingual development. Journal of Child Language. 2012;39:1–27. doi: 10.1017/S0305000910000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez DJ. Demographic change and the life circumstances of immigrant families. Future of Children. 2004;14:17–47. doi: 10.2307/1602792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchman VA, Martínez LZ, Hurtado N, Grüter T, Fernald A. Caregiver talk to young Spanish-English bilinguals: Comparing direct observation and parent-report measures of dual-language exposure. Developmental Science. 2017;20:xx. doi: 10.1111/desc.12425. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gathercole VCM, Thomas EM. Bilingual first-language development: Dominant language takeover, threatened minority language take-up. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2009;12:213–237. doi: 10.1017/S1366728909004015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurtado N, Grüter T, Marchman VA, Fernald A. Relative language exposure, processing efficiency and vocabulary in Spanish–English bilingual toddlers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2014;17:189–202. doi: 10.1017/S136672891300014X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearson BZ, Fernández SC, Lewedeg V, Oller DK. The relation of input factors to lexical learning by bilingual infants. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1997;18:41–58. doi: 10.1017/S0142716400009863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thordardottir E. The relationship between bilingual exposure and vocabulary development. International Journal of Bilingualism. 2011;15:426–445. doi: 10.1177/1367006911403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deanda S, Arias-Trejo N, Poulin-Dubois D, Zesiger P, Friend M. Minimal second language exposure, SES, and early word comprehension: New evidence from a direct assessment. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2016;19:162–180. doi: 10.1017/S1366728914000820. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1366728914000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oller DK, Pearson BZ, Cobo-Lewis AB. Profile effects in early bilingual language and literacy. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2007;28:191–230. doi: 10.1017/S0142716407070117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson TA, Peña ED, Bedore LM. The relation between language experience and receptive-expressive semantic gaps in bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2014;17:90–110. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2012.743960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribot KM, Hoff E. “¿Cómo estas?” “I’m good” Conversational code-switching is related to profiles of expressive and receptive proficiency in Spanish-English bilingual toddlers. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2014;38:333–341. doi: 10.1177/0165025414533225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pham G, Kohnert K. A longitudinal study of lexical development in children learning Vietnamese and English. Child Development. 2014;85:767–782. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoff E, Rumiche R, Burridge A, Ribot KM, Welsh SN. Expressive vocabulary development in children from bilingual and monolingual homes: A longitudinal study from two to four years. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2014;29:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson BZ, Fernández SC, Oller DK. Lexical development in bilingual infants and toddlers: Comparison to monolingual norms. Language Learning. 1993;43:93–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1993.tb00174.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silvén M, Voeten M, Kouvo A, Lundén M. Speech perception and vocabulary growth: A longitudinal study of Finnish-Russian bilinguals and Finnish monolinguals from infancy to three years. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2014;38:323–332. doi: 10.1177/0165025414533748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Houwer A. The absolute frequency of maternal input to bilingual and monolingual children: A first comparison. In: Grüter T, Paradis J, editors. Input and experience in bilingual development. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins; 2014. pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petitto LA, Katerelos M, Levy BG, Gauna K, Tetrealt K, Ferraroi V. Bilingual signed and spoken language acquisition from birth: Implications for the mechanisms underlying early bilingual language acquisition. Journal of Child Language. 2001;28:453–496. doi: 10.1017/S0305000901004718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Houwer A, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL. A bilingual-monolingual comparison of young children's vocabulary size: Evidence from comprehension and production. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2014;35:1189–1211. doi: 10.1017/S0142716412000744. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0142716412000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bialystok E. Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2009;12:3–11. doi: 10.1017/S1366728908003477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giguere D. Master’s thesis. Florida Atlantic University; Boca Raton, FL: 2017. Adult outcomes of early dual language exposure in the majority-minority language context. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Place S, Hoff E. Properties of dual language exposure that influence two-year-olds’ bilingual proficiency. Child Development. 2011;82:1834–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Place S, Hoff E. Effects and noneffects of input in bilingual environments on dual language skills in 2½-year-olds. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2016;19:1023–1014. doi: 10.1017/S1366728915000322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paradis J. Individual differences in child English second language acquisition. Comparing child-internal and child-external factors. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. 2011;1:213–237. doi: 10.1075/lab.1.3.01par. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bleakley H, Chin A. What holds back the second generation? The intergenerational transmission of language human capital among immigrants. Journal of Human Resources. 2008;43:267–298. doi: 10.3368/jhr.43.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammer CS, Komaroff E, Rodriguez BL, Lopez LM, Scarpino SE, Goldstein B. Predicting Spanish-English bilingual children’s language abilities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012;55:1251–1264. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia G, Aaronson D, Wu Y. Long-term language attainment of bilingual immigrants: Predictive variables and language group differences. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2002;23:599–621. doi: 10.1017/S014271640200405848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altan A, Hoff E. Syntactic complexity in L1 and L2 child-directed English. In: Buğa D, CÖgeyik M, editors. Psycholinguistics and cognition in language processing. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoff E, Shanks K, Brundage S. Effects of native speaker status and second language proficiency on lexical richness and syntactic complexity of child-directed speech. 2017 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bedore LM, Peña ED, Summers CL, Boerger KM, Resendiz MD, Greene K, Gillam RB. The measure matters: Language dominance profiles across measures in Spanish-English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2012;15:616–629. doi: 10.1017/S1366728912000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohman T, Bedore LM, Peña ED, Mendez-Perez A, Gillam RB. What you hear and what you say: Language performance in Spanish English bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2010;13:325–344. doi: 10.1080/13670050903342019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Houwer A. Parental language input patterns and children's bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2007;28:411–422. doi: 10.1017/S0142716407070221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hurtado A, Vega LA. Shift happens: Spanish and English transmission between parents and their children. Journal of Social Issues. 2004;60:137–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00103.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribot KM, Hoff E, Burridge A. Language use contributes to expressive language growth: Evidence from bilingual children. Child Development. 2017 doi: 10.1111/cdev.12770. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoff E. The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development. 2003;74:1368–1378. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoff E. How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review. 2006;26:55–88. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirsh-Pasek K, Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Owen MT, Golinkoff RM, Pace A, Suma K. The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychological Science. 2015;26:1071–1083. doi: 10.1177/0956797615581493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huttenlocher J, Waterfall H, Vasilyeva M, Vevea J, Hedges LV. Sources of variability in children’s language growth. Cognitive Psychology. 2010;61:343–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smithson L, Paradis J, Nicoladis E. Bilingualism and receptive vocabulary achievement: Could sociocultural context make a difference? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2014;17:810–821. doi: 10.1017/S1366728913000813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearson BZ. Raising a bilingual child. New York, NY: Living Language; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grosjean F. Neurolinguists, beware! The bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. Brain and Language. 1989;36:3–15. doi: 10.1016/0093-934X(89)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han WJ. Bilingualism and academic achievement. Child Development. 2012;83:300–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kieffer MJ. Early oral language and later reading development in Spanish-speaking English language learners: Evidence from a nine-year longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2012;33:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2012.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tseng V, Fuligni AJ. Parent-adolescent language use and relationships among immigrant families with East Asian, Filipino, and Latin American backgrounds. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00465.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]