Abstract

The Marshallese community of Orange County California is a part of a highly mobile population that migrates between Hawai‘i, Arkansas, Washington, and California. In Orange County, the Marshallese community is primarily centered on faith-based organization in the city of Costa Mesa. Culture and language strengthen the bonds between different Marshallese communities across the U.S., and churches serve as conduits for communication between groups. Culture also places an important role in guiding behavior pertaining to health and social interaction. For instance, as in many other cultures, Marshallese men and women do not speak to each other about health, particularly reproductive health, in an open social setting. In Orange County, one female Marshallese health educator promotes breast and cervical cancer screening by talking informally with women, usually in faith-based settings and in-home visits. This community commentary describes the key cultural considerations and strategies used by the health educator to reach and educate the community.

Keywords: Marshallese women, breast and cervical cancer, sexual health, reproductive health, cultural norms

Background on Population and Cancer Risks

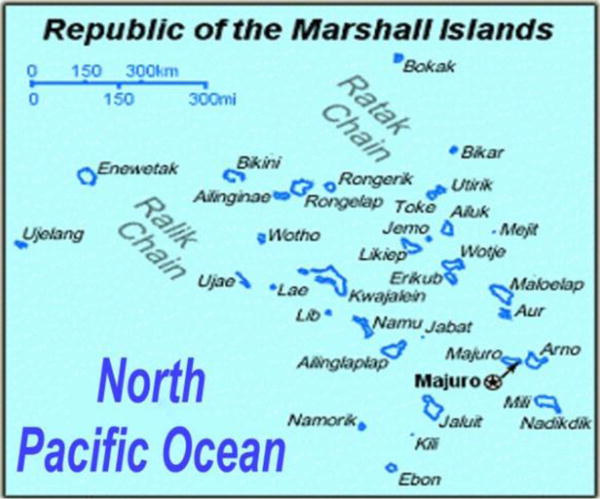

Marshallese are people from the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) that consists of 29 atolls (see Figure 1) with a population of approximately 64,522 people of whom approximately half reside in the Majuro atoll (Central Intelligence Agency, 2010; (Kroon et al., 2004). RMI has a unique history with the U.S., with which it has a compact of free association. Unfortunately, from 1947 until 1958, the U.S. military tested 67 nuclear weapons on the Marshall atolls of Bikini and Enewetak, leaving about approximately 20% of the area uninhabitable (Bouville, 2005). Consequently, cancer is of great concern to the Marshallese population both on the islands and in the US. Cervical and breast cancer are the first and third leading causes of cancer among women in RMI (Kroon et al., 2004), and mortality is high among Pacific Islanders in Orange County (Marshall, Ziogas, & Anton-Culver, 2008). As depicted in Table 1, Dr. Bouville of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute, in a testimony before the Committee on Resources and the Subcommittee on International Relations United State House of Representatives in 2005, stated that fallout radiation from nuclear testing could result in a 9 percent increase in the total number of fatal and non-fatal cancers resulting in about 530 additional cancer cases due to the extremely high radiation doses received (Bouville, 2005). In 2000 there were approximately 6,650 Marshallese in the continental U.S. (US Census Bureau, 2001) representing individuals with high mobility; anecdotal information suggests that Marshallese migration between the states of Hawai‘i, Arkansas, Washington, and California (primarily the cities of Costa Mesa and Sacramento) is common. Costa Mesa in Orange County is home to over 300 Marshallese, which represents approximately 10% of the population in the continental U.S (Hess, Nero, & Burton, 2001) This population is socially organized around churches which replaced traditional Pacific Islander villages as the important social structure for Marshallese community life (Hess et al., 2001). Past studies document the many barriers to cancer prevention and other health services for Marshallese in the U.S., including limited English proficiency, distrust of Americans (due to negative experiences in RMI, including nuclear testing in the Bikini Islands), lack of transportation and medical insurance, and cultural considerations such as modesty during clinical examinations (Choi, 2008; Williams & Hampton, 2005). Despite having the right to free entry into the U.S. (provided by the 1986 Compact of Free Association), they face varying eligibility requirements for public programs such as Medicaid, food stamps and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (Yamada & Pobutsky, 2009).

Figure 1. Republic of the Marshall Islands.

Image obtained from the Republic of Marshall IslandsEmbassy in Washington DC website, http://www.rmiembassyus.org/

Table 1.

Lifetime Predicted Radiation-Related Cancers on the Marshall Islands as of 1954

| Type of Cancer | Rate: High Fallout areas* | Rate: surrounding areas | Percentage of yet to develop or be diagnosed. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia | 60% | 3% | All developed & diagnosed |

| Thyroid | 98% | 64% | 38% |

| Stomach | 78% | 2% | 85% |

| Colon | 94% | 17% | 75% |

| Other Cancers | 46% | 1.4% | 66% |

Rongelap/Ailinginae population. An estimated 87% of all radiation related cancers are predicted from exposure on the northern atolls of Rongelap, Ailinginae, Ailuk, Mejit, Likiep, Wotho, Wotje, and Ujelang (National Institutes of Health, 2004).

In spite of the history of nuclear testing and the predictions by the National Cancer Institute, very little published information exists on the ways to promote cancer screenings among Marshallese women. For instance, Aitaoto and colleagues (2009) found that Chuukese and Marshallese women relied primarily on community leaders and family members for cancer-related health information, with lay educator programs (that included the pastor or the pastor’s wife) as the most effective approach to outreach to the community (Aitaoto, Tsark, Tomiyasu, Yamashita, & Braun, 2009). The purpose of this paper is to share insights on culturally informed lay health education concerns and approaches for Marshallese breast and cervical cancer control in Orange County. The lead author is a Marshallese health educator with over 12 years experience in community outreach and education in Orange County. Given the dearth of research and interventions tailored for the Marshallese population, we hope that this community perspective promotes greater culturally competent and sensitive approaches for Marshallese across the continental U.S.

Cultural Influences on Marshallese Cancer Beliefs and Behaviors

Cultural beliefs regarding cancer and the female body must be understood in order to promote tailored outreach education for Marshallese. Similar to other Pacific Islander populations, cultural norms influence the ways that Marshallese women interact with providers and the Western medical care system (McLaughlin & Braun, 1998; Tanjasiri, LeHa’uli, Finau, Fehoko, & Skeen, 2002). Marshallese women do not generally talk about reproductive health, because the body, especially the female body, is not discussed in public. Women typically do not seek medical attention for reproductive health unless they are pregnant. Marshallese cultural norms maintain strict rules on female-male interaction and female modesty is a strong cultural norm that is pervasive in Marshallese communities. For instance, men and women do not sit on the same side of the isle in church, women will excuse themselves to use the toilet during a gathering while men are present, and Marshallese do not discuss any female-related health issues while men are present (Levy, Taylor, Higgins & Grafton-Wasserman, 1988). These norms influence the degree to which women can and do obtain information about health issues. Thus, opportunities for women to gather together are important for providing safe spaces for sensitive health topics to be discussed (Williams & Hampton, 2005).

Beyond reproductive or sexual health, general health and illness is considered a personal matter and is not talked about by the affected person or his/her family. When someone is sick typically only family are informed and privacy is maintained within the family unit. Often the larger community only learns about a member’s illness at advanced stages of illness or during hospitalization. For instance, Choi (2008) reported that Marshallese migrants in Hawai`i did not seek health care until they perceived a health crisis, usually indicated by severe pain.

Gender of the physician or primary care provider plays a major role as to whether Marshallese women pursue, access, and receives comprehensive health care. If the medical provider is male, women will be discouraged from seeking routine annual or other exams that may involve reproductive health. Pregnancy and terminal illness are the only times Marshallese women will allow a male doctor to provide medical care. Marshallese cultural norms dictate that men and women not discuss any issues involving reproductive health, especially not with persons outside the family and specifically not across genders (Williams & Hampton, 2005). Cultural taboos are less stringent, however, regarding women’s breasts. Traditionally on the islands, women appear bare-chested in public; hence discussion about breasts can happen more easily whether on the islands or in the U.S. While discussion of women’s health does not take place in the presence of men, it may be discussed when women are alone. However, rapport between women and the educator is needed to build trust and comfort in talking openly about women’s health issues (Williams & Hampton, 2005; Hayes, Rollins, Weinberg, Brawley, Baquet, Kaur & Palafox, 2005; Aitaoto et al., 2009). Therefore, the personality and social position of the Marshallese female health educator becomes key in establishing rapport. In addition, the status (such as old age or standing in the church) of the health educator is an important factor.

These characteristics. along with being recognized by Marshallese women as a trained health educator, are essential to establishing credibility, facilitating relationship building between women and physicians, and promoting information-exchange and feelings of empowerment that women can take care of their own health concerns (Choi, 2008, Choi, 2009; Hayes et al., 2005). These characteristics give the community women confidence that they can trust and believe in the information that is provided (Williams & Hampton, 2005).

Conducting Culturally Informed Health Education Outreach

In order to reach Marshallese women ages 20 and older, cancer education must respect and adhere to the cultural norms and structure of the Marshallese community in the U.S. Cultural tailoring of health information, creating culturally appropriate health messages, and methods of delivering messages are of particular importance in the Marshallese community. An important cultural matter is the strict cultural rules that exist for male-female interaction, discussion about health and the human body, and highly personalized interactions that reflect traditional Marshallese communication styles. Thus, cancer outreach education for Marshallese in Orange County involves home visits and church outreach to discuss and share information, and introduce the sensitive topics of reproductive health and cancer. As shown by past research, home visits allow groups of Marshallese community members to meet comfortably and interact on health-related topics (Cortes, Gittelsohn, Alfred, & Palafox, 2001).

For the health education sessions conducted in Orange County, Marshallese women in the community are asked by a health educator to host the educational sessions in their homes. They work together with the health educator to invite Marshallese neighbors to the women’s gathering. Participants are recruited at church and community events. In-person, verbal invitations are the primary means of bringing women to the session. In keeping with the cultural norms, the topic of discussion is generally not widely advertised, but the community women are made aware that there will be a discussion of issues that pertain only to women.

In adherence with cultural norms, all the men of the host house leave to ensure that no men or boys are present when the female guests start to arrive. Adult males make sure that boys are occupied for several hours, so that all women have time to participate and then leave the session before male family members return. Younger girls take care of the babies and female children at home while the mothers and grandmothers attend the education sessions. Cancer education sessions with women (who are usually married) take the form of interactive discussions. The health educator plays the role of facilitator and educator. The discussion is kept conversational and highly interactive with the use of props and participant demonstration. Women participate in role-playing and demonstrating skills such as practicing breast self-exam techniques and talking to their mothers, sisters and daughters about reproductive health and cancer screening. Women are encouraged to get screened for the health of not only themselves but their families, with the role of the mother as caregiver emphasized. All education is conducted exclusively in Marshallese. By the end of a given session, women help each other decide on a date to schedule their pap-test and mammogram, and create a support system to remind each other to conduct their monthly breast self-exams. At no point does the session feel like a classroom; it is more like a group of women having a conversation about a health topic that is of interest to them. The education sessions are designed to be an opportunity to socialize with other women, and to discuss health out of respect rather than necessity.

Church outreach by the health educator occurs one night per week when the church facilities are open to women only, and is usually arranged with assistance from the pastor’s spouse who is seen as an influential female community leader (Aitaoto et al., 2009). During these pre-set evenings, Marshallese women gather to interact and discuss issues of importance to the community. Health topics are introduced at least once a month and generally center on current needs in the community, such as cancer, diabetes, and coronary disease. While home-based outreach offers more flexibility and informal interaction, church outreach requires more structure and formality. The cancer education session is scheduled and the female congregation members are informed ahead of time. At all home and church based sessions, Marshallese language materials and screening referral information (that is either low-cost or no-cost) are distributed. In-language materials for outreach and education in Marshallese have shown to reinforce cultural cohesion and have a positive impact on women’s responsiveness to cancer information (Aitaoto et al., 2009). As noted above, effective Marshallese community outreach must involve churches, social and family networks to not only reach women but also promote the kinds of small group, culturally nuanced discussions that are necessary to address culturally delicate issues (Aitaoto et al., 2009). Using the approaches described in this paper, approximately 800 Marshallese women between the ages of 18 and 75 in Orange County have been educated on breast and cervical cancer early detection, with approximately 60 women assisted to receive a breast or cervical cancer screening examination and 15 receiving follow-up support during treatment over the past 5 years. Similarly efforts have been made by the health educator to reach Marshallese women in San Diego (California), Springdale (Arkansas), and Reed (Missouri).

Lessons Learned

Despite the many benefits to the culturally appropriate strategies described above, there are several limitations and challenges that we have encountered. With home-based outreach, there are few residences that can accommodate more than five to ten women, and sessions are difficult to schedule because most Marshallese women work full-time to provide for their families. With church-based sessions, there are time limits (generally one hour) to the length of the sessions, women who are shy or less talkative have a difficult time speaking up or asking questions, and women are less likely to participate in demonstrations such as breast self-examination. There are also church protocols that must be followed, such as gaining buy-in from female leaders of all of the Marshallese churches in Costa Mesa in order to avoid perceptions of bias or favoritism. These barriers are generally overcome by offering education in home-based settings to women across congregations. Another limitation to health education is that there is only one trained Marshallese cancer educator. It is possible that the lack of resources for training and employment makes the profession of health education less attractive to other Marshallese. This is especially true among younger Marshallese, who are struggling with adherence to traditional Marshallese cultural norms and language, making it difficult for them to conduct linguistic and culturally appropriate cancer education with older adults. Furthermore, logistical barriers are common for Marshallese women, and include competing priorities of family and community, lack of transportation, and other financial restrictions. Similar to Marshallese women in Hawai`i (Aitaoto et al., 2009), women in the U.S. also suffer from limited understanding of breast and cervical cancer; cultural beliefs and norms regarding health-seeking that result in delayed care, and fear of negative screening results that all lead to low rates of cancer early detection.

In order to continue to better serve the Marshallese community in not only Orange County but across the continental U.S., other efforts are also being made. A local community based organization (the Pacific Islander Health Partnership, PIHP) is working on soliciting funds to expand current education efforts. PIHP was founded in 2002 by a group of indigenous Pacific Islanders (including not only the Marshallese but also Chamorros, Fijians, Native Hawaiians, Samoans, Tahitians and Tongans) to promote health through education, training and research in Orange County. These efforts centered on educating the community about cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. There is a growing need to follow-up on women who have been screened to address logistic and social needs; for instance, PIHP has joined Saint Joseph Hospital of Orange in applying for federal funds to develop patient navigation services for Marshallese and other Pacific Islanders in Orange County. With regards to developing the next generation of educators, PIHP and other Pacific Islander organizations are supporting the creation of a cadre of Pacific Islander youth who are interested in health as a profession. As more resources are secured to address cancer disparities in this underserved Pacific Islander population, the Marshallese community will have a greater capacity to implement and evaluate the impact of culturally appropriate health education efforts in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Pacific Islander Health Partnership (PIHP) and the Marshallese community, and especially the Marshallese women who participated in the breast cancer education sessions; Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance (OCAPICA) for their ongoing support; and WINCART: Weaving an Islander Network in Cancer Awareness, Research and Training staff at the California State University, Fullerton Department of Health Science. This publication was made possible by Grant Number U01CA114591 from the National Cancer Institute’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (NCI CRCHD), and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI CRCHD.

References

- Aitaoto N, Tsark JU, Tomiyasu DW, Yamashita BA, Braun KL. Strategies to increase breast and cervical cancer screening among Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Filipina women in Hawai’i. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2009;68(9):215–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY. Seeking health care: Marshallese migrants in Hawai’i. Ethnic Health. 2008;13(1):73–92. doi: 10.1080/13557850701803171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes LM, Gittelsohn J, Alfred J, Palafox NA. Formative research to inform intervention development for diabetes prevention in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Health Education and Behavior. 2001;28(6):696–715. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess J, Nero KL, Burton ML. Creating options: formaing a Marshallese community in Orange County, California. The Contemporary Pacific. 2001;13(1):89–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E, Reddy R, Gunawardane K, Briand K, Riklon S, Soe T, et al. Cancer in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Pacific Health Dialogue. 2004;11(2):70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SF, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. OC Komen Affiliate & UCI Data Project: Breast Cancer Incidence & Prevalence in Orange County, Monograph II - Disparities in Breast Cancer Mortality in Orange County (Journal No Monograph 2) Irvine, California: University of California, Irvine; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin LA, Braun KL. Asian and Pacific Islander cultural values: considerations for health care decision making. Health Social Work. 1998;23(2):116–126. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjasiri SP, LeHa’uli P, Finau S, Fehoko I, Skeen NA. Tongan-American women’s breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors. Ethnicity & Disease. 2002;12(2):284–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US. The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population: 2000. 2001 Retrieved. from. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DP, Hampton A. Barriers to health services perceived by Marshallese immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2005;7(4):317–326. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-5129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Pobutsky A. Micronesian migrant health issues in Hawai`i part 1: background, home island data and clinical evidence. Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;7(2):16–31. [Google Scholar]